The forested land in the United States is an asset that is owned and managed by federal, state, and local governments, families,1 and other private groups, including timber investment management organizations and real estate investment trusts. More than 10 million family forestland owners manage the largest percentage (35 percent) of the nation’s forestland acreage and the majority (62 percent) of its privately owned forestland (U.S. Department of Agriculture, 2012). The Forest Service of the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), which is responsible for the stewardship of all of the nation’s forests, has long worked with private owners of forestland on forest management and preservation, but all forestland is facing intensified threats because of the long-term effects of global climate change. The Forest Service recognizes that family forestland owners play a key role in protecting forestland and is working to identify optimal ways to engage this diverse group and support them in mitigating threats to the biologically diverse land they own.

REPORT FOCUS AND SCOPE

The task of engaging with family forestland owners is complicated by the fact that they receive technical, financial, and educational assistance

__________________

1Family forestland owners are defined by the U.S. Forest Service as families, individuals, trusts, estates, family partnerships, and other unincorporated groups of individuals who own forestland.

from a wide variety of public and private foresters, who themselves need to have a better understanding of how to engage forestland owners to deal with climate change. In addition, to effectively convey forest and climate change information in a manner that motivates action by family forestland owners necessitates not only a strong grasp of the science related to forest ecology and climate change but also an understanding of social, psychological, and educational theories on motivation, behavior change, and communication about complex issues.

The Forest Service and the National Institute for Food and Agriculture (NIFA) of the USDA asked the National Research Council’s (NRC) Board on Science Education and Board on Environmental Change and Society to hold a public workshop, the fourth in the Climate Change Education Roundtable series, to explore approaches to the challenge of preparing the professionals (state foresters, extension agents, private forestry consultants, and other service providers) who advise or otherwise intersect with private family forestland owners on how to take climate change into consideration when making decisions about their forests. The Forest Service and NIFA were particularly concerned that most of these intermediaries lacked relevant expertise from the social and behavioral sciences and adult education. In response, an eight-person planning committee—the Steering Committee on Engaging Family Private Forest Owners on Issues Related to Climate Change—with expertise in human behavior, natural resource economics, risk assessment, communication, outreach and extension, and political and social sciences was assembled to plan and convene the requested public workshop. This two-day workshop, held in August 2013, focused on ways that findings from the behavioral, social, and educational sciences2 can be applied in engaging private individual, family, and community forestland owners in conversations about preparing for the impacts of climate change. The steering committee was charged with addressing the following:

- Threats to forests posed by climate change and human actions.

- Private forestland owners’ (individual, family, and community forest owners) objectives, values, knowledge, and dispositions about forest management, climate change, and related threats.

- Strategies for improving communication between forestland owners and service providers with respect to forest management in the face of climate change.

The workshop provided an opportunity for Cooperative Extension

__________________

2For convenience, these disciplines, which include economics, sociology, psychology, and political science, are generally referred to as the “social sciences” in this report.

foresters,3 program administrators, nonprofit organization leaders, and others who are in a position to influence those who own and manage forests to interact with researchers and to reflect on how research can support strategies and tactics for effective communication and engagement with forestland owners. (See Appendixes B and C for the agenda and a list of participants.)

This summary, which was prepared by rapporteurs, describes the presentations and discussions that took place at the workshop. The views expressed in the report are those of individual workshop participants and do not necessarily represent the views of all workshop participants, the planning committee, or the NRC. The summary begins, in this chapter, with an overview of the ways in which U.S. forestland is likely to be affected by global climate change and other factors. Chapter 2 discusses the characteristics of the private owners of U.S. forestland. Chapter 3 discusses examples of strategies regional and local groups have used to engage with forestland owners. Chapter 4 discusses ideas drawn from the social sciences that can support productive engagement with forestland owners. Chapter 5 discusses ideas, outstanding questions, and possible next steps that emerged from discussion throughout the workshop.

CHALLENGES TO FORESTLAND

James Finley, professor of forest resources at The Pennsylvania State University, and David Cleaves, climate change advisor to the Chief of the U.S. Forest Service, set the stage with reflections on the challenges facing forests and their owners. Landowners value healthy forestland and want to protect it, Finley observed. Forestland owners’ respect for the value of their land is a “logical platform” from which to address this group about the threats posed by climate change and human action, in his view. Healthy forestland is “an economic, an ecological, and a social value” that is critical not only for the private forestland owners who control and hold that land right now, he stated, but also for all U.S. residents, who will continue to benefit from the existence of that land.

Cleaves explained that the U.S. Forest Service and the USDA, and all other institutions that serve the forest sector, are eager for guidance from the social sciences in responding not only to a changing climate but also to demographic changes among forestland owners and other changes in the ways people interact with forests. Dynamic forests are part of the solution to climate change, he noted, because “if you want more carbon sequestration, you have to have healthier forests…. To get healthier forests, you

__________________

3The Cooperative Extension is a nationwide structure for providing information to agricultural producers and others; see http://www.csrees.usda.gov/Extension/ [November 2013].

have to understand the system—you can’t just write a policy and turn it on and see what happens.”

James Vose, research ecologist with the U.S. Forest Service, provided a detailed look at how forests in the United States are changing. The science of climate change is progressing rapidly, he pointed out, and new information is constantly being added to the climate assessment process. He based his presentation on the USDA report Effects of Climatic Variability and Change on Forest Ecosystems: A Comprehensive Science Synthesis for the U.S. Forest Sector (U.S. Department of Agriculture, 2012), which summarizes current research and discusses adaptation and mitigation strategies.

Drawing on that report, Vose looked first at how climate change will affect forest ecosystems in the United States. Forests develop in response to their physical environments, biological dynamics, and human decisions about their use, he explained. Ecosystems, climate stressors, and human actions are highly interconnected, so climate scientists use the word “anthropocene” to describe the world climate and all of its influences.

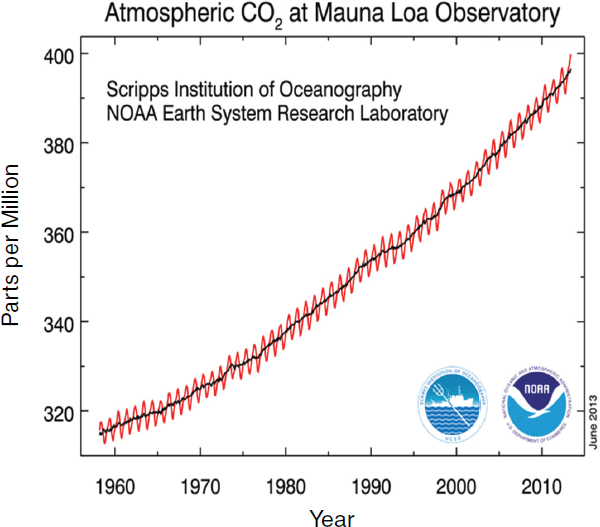

The changes that threaten forests begin with substantial increases in the emissions of greenhouse gases (see Figure 1-1), which have led to an increase in average overall global temperature of 1.4°F over the past 100 years, Vose explained. This increase has meant a significant loss of Arctic ice, an 8-inch rise in sea level since 1870, and an increase in heat waves and extreme temperatures during the past 20 years. The 2012 USDA report focused on using observations of how ecosystems have already responded to observed increases in temperature and other changes to provide some guidance as to what effects are likely in the future.

Predictions that were made 20 to 30 years ago, he explained, have largely been confirmed. At the same time, a number of extended experimental studies have now been operating for long enough that their results also reinforce climate scientists’ capacity to make predictions about the future. The most widely used tools for making these predictions are forecasting models, such as the General Circulation Models or Global Climate Change Models, Vose noted. These types of models depict the range of possible scenarios and outcomes that can be expected under different sets of assumptions about such factors as carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions, economic conditions, and resource use.

Modeling forecasts, together with the growing body of empirical evidence, indicate that climate change will have significant effects on U.S. forests, Vose explained, although different assumptions about CO2 emissions, economic conditions, resource use, and other variables yield somewhat differing projections. Researchers in this area generally incorporate minimum and maximum estimates into their calculations to arrive at a realistic predicted range of outcomes. Throughout his presentation, Vose used estimates and predictions that fell in the mid-range of changes

FIGURE 1-1 Change in atmospheric CO2.

SOURCE: Available: http://www.esrl.noaa.gov/gmd/ccgg/trends/ [May 2014].

that could occur, between the extreme ends of the continuum of possible scenarios.

The direct effects will include increased temperatures, changes in the amount and extremity range of precipitation (which will mean more frequent and more severe droughts for many parts of the world), elevated CO2, and a rise in sea levels. For forests, these changes will mean higher rates of growth where nutrients and soil moisture are available; reduced growth in forests with more limited water or that are affected by other disturbances; higher mortality of vegetation in drier areas; changes in habitat that will affect the distribution of plant and animal species; and changes in the hydrologic, nutrient, and carbon cycling processes.

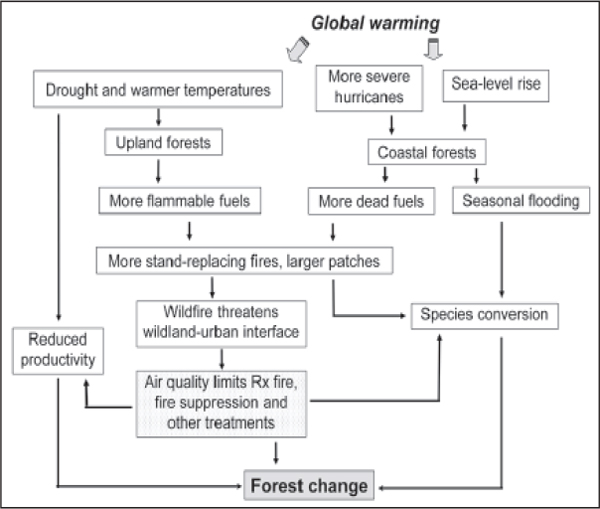

Indirect effects that come with these changes with particular significance for forests will include increased risk of fire, changes in insect and pathogen populations, and growth of invasive species. Combinations of stressors that interact with one another, known as “stress complexes,”

FIGURE 1-2 Stress complexes for upland and coastal forests in the southern United States.

SOURCE: Vose et al. (2012).

will be affected by a warmer climate; Figure 1-2 illustrates how this sort of interaction may accelerate changes, using the example of forests in the southern United States.

The distribution and abundance of tree species will change, Vose added, because changing conditions will substantially alter many habitats and make them unsuitable for the species that currently grow in them. There will be what he termed losers and winners: Some species may need to move north by as much as 400 to 800 km (250 to 500 miles), and the habitat changes may occur faster than species can migrate; other species’ habitats may expand. Hydrologic and biochemical cycling will also change, in response to the combined effects of the changes in climate, Vose explained. The results for forests will include changes in snowfall and snowmelt, and increases in flooding, erosion, and landslide potential. Eastern forests are likely to store greater amounts of carbon—a benefit

that may be offset by loss of forestland, drought, and other disturbances—while western forestland will store less carbon.

Vose emphasized that while the precise nature of the changes will be specific to particular regions, the big picture is one of “multiple, co-occurring stresses and disturbances that are likely to be much more severe in combination than if any of them occurred singly.” Climate change is a large-scale phenomenon, he added, but the specifics in particular regions will influence the management response. Essentially, he said, the two management responses are to mitigate the changes and to adapt to them.

MANAGEMENT RESPONSES

The primary means of mitigating the harm, Vose explained, is to manage—slow down—the release of carbon into the atmosphere. U.S. forests capture about 16 percent of the carbon emissions from U.S. fossil fuel use at present, he noted, and “there is certainly opportunity to influence that through policy and action.” Helping forestland adapt to inevitable changes by preparing systems and species, however, is the area where private forestland owners can play the largest role. Cleaves, in discussion, highlighted this point, noting that the USDA stresses retaining forestland, restoring function to forests with problems, and regenerating forests that have been depleted.

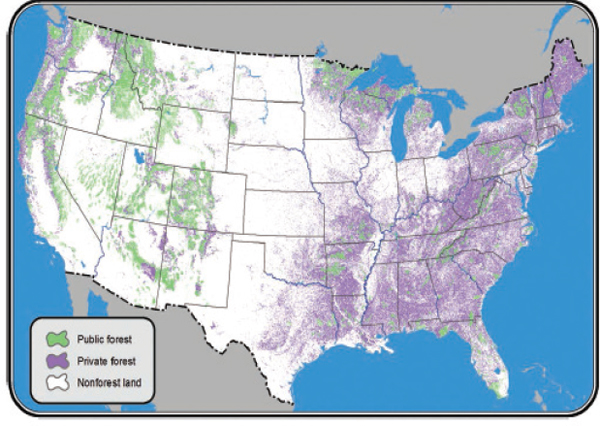

Figure 1-3 shows the distribution of privately owned forestland in the United States, and illustrates that in the eastern United States, the majority of forestland is privately owned. Thus, particularly in that region, private decisions about land use—whether to preserve it as forest or use it for another purpose, and whether to manage it—will play a critical role. (See Box 1-1 for the U.S. Forest Service’s statement of its approach to forest management.)

Projected growth in human population will vary across the United States, Vose noted, with the most intense growth clustering around urban areas. The growth projected by 2060 will mean that significantly more land will move into the urban land use category, and this will happen at the expense of cropland and forestland. The number of U.S. acres that were forestland reached its lowest point in the 1970s, Vose noted, and has increased since then. Current projections indicate that by 2060, that number will again be at roughly the 1970 level, with most of the loss occurring in the private forestland of the eastern United States.

While much of this picture is quite daunting, Vose concluded, “Management activities can really influence the severity and the direction of the response.” Landowners and forest managers, he added, are already accustomed to dealing with such external stresses as wildfire risk, insect outbreaks, and diseases. The pace and magnitude of climate change will

FIGURE 1-3 U.S. forestland ownership.

SOURCE: Walthall et al. (2012, p. 99).

BOX 1-1

The U.S. Forest Service’s Approach to Forest Management

The overriding objective of the Forest Service’s forest management program is to ensure that the National Forests are managed in an ecologically sustainable manner. The National Forests were originally envisioned as working forests with multiple objectives: to improve and protect the forest, to secure favorable watershed conditions, and to furnish a continuous supply of timber for the use of citizens of the United States. Forest management objectives have since expanded and evolved to include ecological restoration and protection, research and product development, fire hazard reduction, and the maintenance of healthy forests. Guided by law, regulation, and agency policy, Forest Service forest managers use timber sales, as well as other vegetation management techniques such as prescribed fire, to achieve these objectives. These activities have captured substantial public attention, and in some cases, become hotly debated issues.

SOURCE: Available: http://www.fs.fed.us/forestmanagement/aboutus/index.shtml [January 2014].

call for similar management responses, but with greater intensity and at a greater scale. The optimal management response will depend on the local circumstances, and will depend on “a lot of give and take, partnerships, and a lot of learning,” he added. Scientists, landowners, policy makers, and land managers will need to work together to develop management plans, Vose said. But, he added, forestland owners will need to recognize that a tipping point4 has been reached, and that “they could lose their forest as they know it in a very rapid sequence of events—wildfire, disease, drought, etc.”

Vose closed with the observation that “the amount of private land in the United States means that to keep forest ecosystems healthy, productive, and providing the services that society depends on, the private landowner [will be] critical—this can’t be addressed just on public lands.”

__________________

4A tipping point is when there is a change from one stable state to another stable state; after the new state occurs, it may be impossible to return to the initial state.

This page intentionally left blank.