5

Technical Women in Small and Medium Businesses

Graduate students in a Carnegie Mellon University capstone course presented their research on women working in information technology (IT) in small and medium-sized businesses.

Channing Martin, manager of the Carnegie Mellon University Heinz Graduate Systems Project, introduced the research project. She and her five colleagues attend Heinz College, where they are studying public policy and management in a 2-year program, the first year of which is on the Pittsburgh campus and the second in Washington, DC (with weekly meetings held at the National Academies). Students can work full time while continuing their studies in the evenings, applying lessons from the lecture-style classes to real-world problems. She explained that none of the six women have technical backgrounds, but “we all felt strongly about women in IT, and we wanted to use our policy backgrounds to effect change in that space.”

BACKGROUND

Liz Schuelke said that at the beginning of the year, working with Catherine Didion, the students decided to focus on what has kept women’s representation in IT jobs at 20 percent for the last decade. The group first conducted a literature review of research on barriers that deter women from entering and staying in the technical workforce; after reviewing 300 abstracts, they read 90 articles. “While there’s a lot of research on what keeps women from entering the field and what’s making them leave, all of it was geared toward big businesses and large IT firms,” said Schuelke.

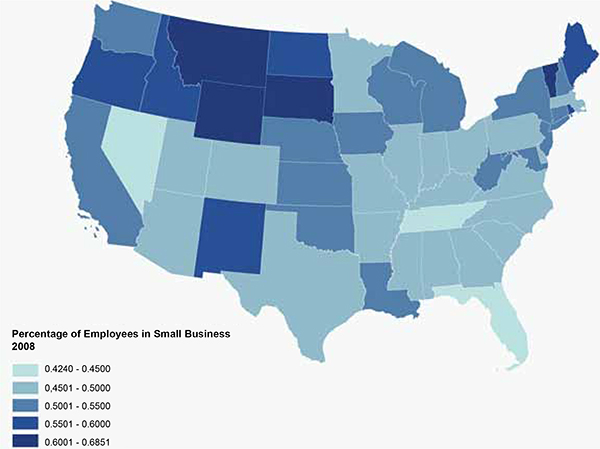

FIGURE 5-1 Percentage of employees in small businesses, by state, 2008. SOURCE: “Statistics of uS Businesses: 2008: All Industries united States.” uS Census Bureau. Available at www.census.gov/epcd/susb/latest/us/uS--.HTM.

FIGURE 5-2 Women control 80 percent of consumer decisions but design only 10 percent of IT products and services. SOURCE: Harris, K., and M. raskino. 2007. Women and Men in IT: Breaking Sexual Stereotypes. Stamford, CT: Gartner.

Because most women actually work in small businesses, the group decided to see whether the barriers are the same in small businesses and whether change can be effected differently there.

The students also focused on small businesses because they control a large share of the economy, Schuelke explained: over 90 percent of companies in the United States employ fewer than 500 employees, and these companies account for half of the American payroll. In nearly every state, at least 45 percent of the working population works for a small business (Figure 5-1).

The students conducted a case study of eight companies across the country. They spoke to hiring managers and staff members to learn about the companies’ hiring efforts and the training environment once employees have been hired. The students also surveyed 39 male and female IT employees in a variety of roles at these companies, ranging from Web development and software design to IT maintenance and database administration, to learn about their experiences: how they found their jobs, how comfortable they felt in the environment, and what training and/or mentoring programs were available to them.

Women make up about 45 percent of the small business workforce—but only 20 percent of the IT workforce. Why would a small business care about changing this statistic? Schuelke asked. Because women are consumers and make a lot of the decisions in purchases that impact small businesses (Figure 5-2).

One software development firm told the students that over half of its customers are women, but not a single one of its developers is. The firm’s representative acknowledged that “Our developers can’t talk to the mom, or the young professional woman, in the way that an IT woman could.” He asked, “How do we better reach that consumer base?”

If small businesses owners are persuaded of the need to make changes, continued Schuelke, how will they make these changes? The students sought to identify interventions that would be feasible for small businesses to do in the near term. They looked at words that keep women away, and spaces that make them leave, and how to make the IT culture work for everyone. For example, the students determined that the language of job postings deters women from applying. When they surveyed the employees, the students found that, although the companies reported intensive use of websites (e.g., Monster, the company’s website, CraigsList) for job postings, only 13 percent of the women found their jobs online, in contrast to 48 percent of the men surveyed.

The literature review turned up job posting language that is consistently associated with masculine occupations versus feminine occupations and may deter women from applying. The students developed a simple resource for use in job postings; for example, substitution of the word “understand” instead of “analyze,” “establish” instead of “determine.” The phrase “works well in a competitive environment” might deter a female applicant, who would respond more favorably to “knows how to cooperate in a supportive team environment.” This is an intervention that doesn’t have to go through a lengthy HR process, said Schuelke; it could be applied immediately and have a real impact on the number of women putting their names in the hat.

INFLUENCE OF THE PHYSICAL ENVIRONMENT

Angie Im described physical spaces that induce women to leave IT jobs. Images of videogames and Star Trek are considered stereotypical cues associated with computer science and computer engineering, she continued. A study at the University of Washington found that women demonstrated an aversion to these images in multiple scenarios, such as picking a team to work on or an environment they want to be in.1 The study touches both on getting desirable candidates hired into a company’s workspace and keeping them happy once they are hired.

While over 90 percent of men reported feeling at least somewhat comfortable (with physical space), only 63 percent of women did.

~ Carnegie Mellon study group

With this information in hand, the students explored concerns associated with physical space. They asked

_________________

1Cheryan, S., Plaut, V.C., Davies, P.G., and Steele, C.M. 2009. “Ambient belonging: How stereotypical cues impact gender participation in computer science.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 97(6):1045–1060.

employees how comfortable or out of place they felt in the company’s common spaces, such as meeting rooms or lounges: while over 90 percent of men reported feeling at least somewhat comfortable, only 63 percent of women did.

The students also asked employers, “Do you think your physical space makes women feel comfortable?” One employer responded, “It’s pretty dry, it’s pretty technical. There’s no flowers or other random things. We do have plans to liven up the environment.” But he said that there is nothing that would make women feel uncomfortable, and that they have the same seating arrangements as other developers. “As an aside,” Im noted, “there’s a large oil painting of the Star Trek Enterprise at the entrance to this company, and the business is named after a work of science fiction.” Many of the responses show that there’s a disconnect between what employers think a diverse group of employees need and what the employees actually may want, she said.

Im then showed an image of the workspace at Mozilla in Toronto, which was voted #1 on Gawker’s list of worst tech workspaces (Figure 5-3). Not all tech workspaces look like this, she said, but many do.

Furthermore, none of the eight companies in the study integrated their IT teams; all were separated from the rest of the office. This separation deprives the IT staff of the benefits of the larger corporate environment: the collaboration and dynamic culture often touted by HR employees. Employers need to create opportunities for IT staff and, in particular, women to engage with other members of the office and develop collegial bonds and relationships, said Im. The students are recommending that small businesses integrate IT employees across the rest of the company’s offices rather than separating them, usually by walls in a windowless room. Seating IT employees where they are visible to the rest of the office could create a more inclusive environment, she said.

OPPORTUNITIES FOR SMALL BUSINESSES

Albery Melo observed that most of the studies reviewed focused on how women could assimilate into the dominant organization, instead of looking at how organizational environments could be adapted to accommodate diverse populations, including women. This is a missed opportunity, but small businesses usually are able to make changes to their physical space more quickly than large organizations.

The way women perceive the IT industry may also be a barrier, said Melo. Many see computer science and computer engineering as challenging to and incompatible with their communal goals—they do not see the IT fields as places where they can do work that benefits society, where they can make a difference in the way that, for example, a doctor is seen to do. Like the IT fields, medicine started out as an industry that was predominantly male, but women have been able to thrive in medicine.

It’s not just women who have negative perceptions of the field, said Melo: those in the field have negative views of women. IT employers tend to place women in roles that are oriented toward administration, documentation, or training, because they are often perceived as being more detail-oriented and less technical.

FIGURE 5-3 Example of separated IT workspace.

To mitigate these barriers and encourage the recruitment and mentoring of women in IT, Melo and her colleagues propose that small businesses implement mentoring programs. These can be highly effective, especially if women are paired with female colleagues. A mentor can help a woman become socialized to the ways of the organization and guide her in her professional development. Of the employees surveyed, 83 percent said that mentoring had a positive impact on their decision to stay in their IT position; no respondent said that it had a negative effect. However, more than half of the respondents stated that no such programs were offered (or they didn’t know about them)—another missed opportunity, but, again, one that small businesses can easily redress.

Because not all small businesses may have the resources or staff to implement mentoring programs, Melo and her colleagues suggested the promotion of membership in professional technical organizations. These organizations can be effective for employees and serve as platforms to share best practices. If internal networks are not feasible, external networks may be a great alternative for small businesses.

Melo reiterated that, unlike bigger businesses, small businesses have the flexibility to propose and implement these interventions rapidly, rather than going through a

potentially cumbersome process of approvals. For example, hiring managers could be quickly trained to write less biased job postings—just changing a few words could increase the company’s ability to recruit women. Similarly, small businesses are not constrained by the dispersion of several thousand employees in several buildings; they can work directly with the space they are in, using desks and communal spaces to integrate their IT department with the rest of their personnel. And while they might not have the resources or staff for a formal mentoring program, they can draw on professional technical societies as a resource and source of support for their technical staff.

In closing, Martin urged workshop participants from professional societies to share the students’ recommendations with their members who are employees or employers at small businesses. She also explained that, given more time, they would like to explore more questions: Where do women go when they leave their IT positions? Do they go to a different or larger firm, or do they leave the technical workforce altogether? To gain more insight into the small business experience, it might be useful to target employees who left large businesses to work in small businesses and see how the survey results differ from respondents who have experience only in small and medium businesses. Last, they would like to research changes in organizational culture over time: Would older men with children have priorities that align more with many women’s priorities than younger men without families?

DISCUSSION

Nadya Fouad observed that one of the things she and Singh found in their study was that neither the women who stayed nor those who left identified their experience as sexist. She also agreed that smaller companies are more amenable to change: It might suffice to hire just one or two people to change the environment of a small business; the same would not be true at a company as large as IBM.

Another participant wondered whether the geeky pictures were something the students perceived as uncomfortable or if that perception was reported in the literature. She related her own experience working on the manufacturing floor of a high-tech company, when she and her colleagues had to worry about seeing far more offensive material in someone’s toolbox. “I want you guys to understand that we’ve come a long way, baby,” she said.

Carnegie Mellon student Emily Blakemore explained that she and her colleagues wanted to examine a couple of specific aspects to get at the impact of culture, and they selected the physical space and how it is decorated. The University of Washington study in question focused on smaller IT firms and the sense of “ambient belonging”—the idea that all employees want to feel that they belong in their environment—and found that physical environment and culture currently deter women from staying in IT. The study considered Star Wars posters, paint color on the wall, and books on the bookshelf, and reported that women felt less sense of belonging and less interest in the company when there were stereotypical Star Trek posters on the wall.

Given the discussion of words to use in job postings, Kristina Wagstrom from the University of Connecticut asked whether the students found anything in the literature on whether women applicants were looked upon more favorably when they used words like “analyze” instead of “understand” in their applications. Schuelke said they didn’t find studies of cover letters, but thought the question deserved research. Erin Cadwalader from the Association for Women in Science commented that there is a fairly sizable body of research on the subject, and it pertains to letters of recommendation as well.

Romila Singh asked whether the students had had a chance to share their findings and recommendations with the companies they surveyed. Im explained that that was one of the incentives they offered the companies for participating: the employers would receive a summary of the findings in which it would not be possible to identify the other companies.

Kathleen O’Hara from Virginia Tech noted that when she worked in a small nonprofit company, the IT staff served as liaisons “between the technical world and the ‘human’ world” and they had a lot of interaction. They needed to have patience, for example, and the ability to articulate issues, but the management didn’t appreciate this aspect of their work and evaluated the IT section entirely on the technical aspects.

She asked what types of businesses the students had surveyed. Sara Raju explained that of the eight companies six were small businesses, one was a medium-sized business (about 800 employees), and one was a small nonprofit. They were in a range of industries—an online clothing company, for example, a law firm, and one or two technology firms.

Im noted that when there are small teams with their own individual cultures, it is important to pay attention to the possibility that someone on the team might not connect with that culture. And there should be ways to help all team members feel valued and connected to the company and the mission of the work, even if they’re part of the smaller culture.

Didion invited consideration of places where technology and engineering are done outside of larger entities. For example, there are a lot of women engineers at NASA, but that work is increasingly being contracted out—a trend that raises questions about the communities and cultures where engineering and technology will be done in the future.