2

Institutional Landscape for Coastal Risk Management

Responsibilities as they relate to coastal storm risks are shared among numerous institutions within local, state, and federal governments. Planning, zoning, and building ordinances—key elements of disaster preparedness—are primarily the responsibilities of local governments. Mitigation measures, such as raising homes and other coastal risk reduction strategies, can involve federal, state, and local agencies in varying capacities. Response and recovery following a major event involves numerous federal agencies to assist local and state governments. Additionally, several federal agencies provide data and tools to support planning at national, regional, and local levels. The private sector and nongovernmental organizations also have roles in risk management and disaster recovery, particularly at the community level. This chapter describes the major roles of federal agencies in coastal risk management, the roles and responsibilities typically borne by state and local governments, and federal actions that seek to provide a consistent national approach across these diverse programs. A detailed description of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) planning, authorization, and funding process is included to provide context for this complex landscape of coastal risk reduction efforts. The chapter concludes with a discussion of the alignment of current responsibilities, resources, risks, and rewards, with regard to coastal risk management.

FEDERAL AGENCY ROLES IN COASTAL RISK MANAGEMENT

Numerous federal agencies have roles in coastal risk management in the United States as reflected in legislation, executive action, and agency

initiatives. There are four key agencies that share the bulk of the responsibility: the USACE, the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). Carter (2012) describes the USACE as the “principal federal agency involved in federal flood management investments and activities and flood-fighting.” FEMA, under the Stafford Act and other legislation, has primary responsibility for disaster assistance and mitigation efforts and federally backed flood insurance. HUD provides funding for economic recovery of communities after a disaster, especially within low- and moderate-income populations. NOAA provides critical weather and climate information, as well as decision support tools to assist state and local coastal resource managers to assess potential impacts of storms.

A substantial amount of the funding for federal hazard and coastal risk–related programs is provided in response to national emergencies such as Hurricanes Katrina, Irene, and Sandy, rather than through annual appropriations. A summary of agencies and programs funded by the 2013 Hurricane Sandy Disaster Relief Act in Table 2-1 provides an illustrative snapshot of the number of agencies involved. It also reflects the significance of investments in federal housing programs, transportation, small business and public health programs, and other programs not traditionally associated with coastal hazard management and recovery.

This section outlines the major federal hazard management programs within the major agencies that contribute to various elements of coastal risk reduction and discusses recent federal coordination efforts.

U.S. Army Corps of Engineers

Hurricane and storm damage reduction is only one of the missions of the USACE that shapes the agency’s coastal risk reduction efforts. Other related USACE missions include flood risk management, emergency operations, ecosystem restoration, and interagency and international services. On the basis of a range of authorities (see Box 2-1), the USACE—with congressional appropriation—works with local sponsors to examine the feasibility of coastal risk reduction–related projects, ranging from beach nourishment to barrier island restoration to engineered storm barriers (see Chapter 1). The USACE designs and constructs these projects contingent upon project-specific congressional authorization and appropriations. A list of USACE coastal storm risk management projects on the East and Gulf Coasts is provided in Appendix B. The USACE has also been tasked to undertake coastal risk reduction studies or efforts under specific authorizations limited to a particular area or event.

TABLE 2-1 Federal Agencies and Programs Funded by the 2013 Hurricane Sandy Disaster Relief Act

| Agency | Component | Program or Appropriation Account | Amount (million $)a |

| Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) | Community Planning and Development | Community Development Fund | 16,000 |

| Department of Transportation (DOT) | Federal Transit Administration | Public Transportation Emergency Relief Program | 10,900 |

| Federal Highway Administration | Federal-Aid Highways—Emergency Relief Program | 2,022 | |

| Federal Railroad Administration, Federal Aviation Administration | 148 | ||

| Department of Homeland Security (DHS) | Federal Emergency Management Agency | Disaster Relief Fund | 11,488 |

| Disaster Assistance Direct Loan Program Account | 300 | ||

| U.S. Coast Guard | Acquisitions, Construction, and Improvements | 274 | |

| Department of the Army | USACE | Construction, flood control and coastal emergencies, and other | 5,350 |

| Department of the Interior (DOI) | Office of the Secretary | Departmental operations | 360 |

| National Park Service | Construction and preservation | 398 | |

| Fish and Wildlife Service | Construction | 68 | |

| Small Business Administration (SBA) | Disaster Loans Program Account, salaries, and expenses | 804 | |

| Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) | Office of the Secretary, Public Health and Social Services Emergency Fund | 800 | |

| Agency | Component | Program or Appropriation Account | Amount (million $)a |

| Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) | State and Tribal Assistance Grants | 600 | |

| Leaking Underground Storage Tank Fund | 5 | ||

| Department of Commerce (DOC) | National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration | Construction; Operations, Research, and Facilities | 326 |

| Department of Veterans Affairs | Administration, construction, medical services | 237 | |

| Department of Agriculture (USDA) | Emergency conservation, commodity assistance, capital improvement | 228 | |

| Department of Defense | Navy, Army, Air Force, National Guard | Military construction, operation and maintenance, and management funds | 113 |

| Department of Labor | Employment and Training Administration | Training and Employment Services | 25 |

| Department of Justice | Federal Prison System and Federal Bureau of Investigation | Buildings, Facilities, Salaries, and Expenses | 21 |

| National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) | Construction and Environmental Compliance and Restoration | 15 | |

| General Services Administration (GSA) | Real Property Activities, Federal Buildings Fund | 7 | |

| Total amount of appropriations | 50,510 | ||

aThe majority of appropriation accounts that received funding under the Disaster Relief Act were categorized as nondefense discretionary spending and therefore were subject to an additional reduction of 5.0 percent of their budgetary resources due to sequestration, not reflected here. Accounts that were categorized as nondefense mandatory spending were subject to a 5.1 percent reduction, and accounts that were categorized as defense discretionary spending were subject to a 7.8 percent reduction. Some accounts were exempt from sequestration as well. The actual sequestration of Disaster Relief Act funds in a program, project, or activity within an account may vary, depending on other sources of sequestrable funding in the program.

NOTE: Only those programs receiving $5 million or greater are included here. SOURCE: Modified from GAO (2013).

BOX 2-1

Evolution of USACE Authorities Related to Shore Protection and Coastal Risk Reduction

- Rivers and Harbors Act (1930)—Authorizes USACE to conduct shore erosion control studies.

- Flood Control Act (1946)—Authorizes emergency bank-protection works.

- P.L. 79-727 (1946)—Establishes federal policy to assist in the construction, but not maintenance, of works to protect publicly owned shores of the United States against erosion.

- P.L. 84-99 (1955)—Authorizes emergency management activities, including disaster preparedness, emergency response, and protection or repair of threatened shore protection works that are federally authorized.

- P.L. 84-826 (1956)—Provides federal assistance for periodic beach nourishment on the same basis as new construction, for a period to be specified by the Chief of Engineers.

- P.L. 86-645 (1960)—Authorizes the USACE to provide planning guidance and technical services to state, regional, and local governments at full federal expense to improve floodplain management.

- P.L. 87-874 (1962)—Increases the proportion of construction costs borne by the federal government for beach erosion control and shore protection projects.

- P.L. 89-72 (1965)—Specifies that recreation benefits shall be taken into account in determining the overall benefits.

- P.L. 90-483 (1968)—Section 111 authorizes to study, plan, and implement structural and nonstructural measures for the mitigation of shore damages attributable to federal navigation works.

- Water Resources Development Act (WRDA, 1974)—Section 22 authorizes the USACE to provide technical planning assistance (with 50 percent federal cost share) related to water resources development, including flood risk reduction.

- WRDA (1976)—Section 156 authorizes extension of federal participation in periodic beach nourishment, up to 15 years from initiation of construction.

- WRDA (1986)—Section 103(d) specifies cost sharing for various project purposes. Section 934 increases to 50 years the authorized period of time federal participation can be extended in periodic beach nourishment after the date of initiation of construction.

- WRDA (1999)—Section 215 modifies cost sharing for projects and for periodic renourishment.

- WRDA (2007)—Section 2018 reaffirms policy to participate in renourishment projects. Establishes preference for areas with an existing federal investment, and where impacted by navigation projects or other federal activities.

SOURCE: C. Bronson, USACE, personal communication (2013).

To support project design and enhance federal, state, and local coastal risk reduction efforts, the USACE also conducts coastal risk-related research and develops modeling and sea-level rise mapping tools through its Engineer Research and Development Center and Institute of Water Resources. Through its Floodplain Management Services and Planning Assistance to States programs, the USACE also provides technical and planning assistance to state and local governments to improve flood risk management. In addition, the USACE has some limited ongoing general program authorities to address shoreline erosion, manage sediment resources, and encourage beneficial uses of dredged materials.

As shown in Table 2-2, the average budgets for USACE coastal flooding and storm damage reduction efforts represent a small fraction (ranging from 1.2 to 4.1 percent) of the total Civil Works budget. The vast majority of funds for USACE coastal risk reduction efforts are through emergency supplemental appropriations, passed by Congress in response to specific national disasters (Tables 2-1 and 2-3). Major hurricane risk reduction projects such as the New Orleans Hurricane and Storm Damage Risk Reduction System (HSDRRS), the Hurricane Sandy rebuilding projects, and the North Atlantic Comprehensive Study were funded through emergency supplemental appropriations. Between FY 2008 and FY 2012, $493 million was appropriated for USACE coastal storm risk management efforts through the annual budgeting process, while at least $12.8 billion was allocated for coastal risk projects via supplemental appropriations (Tables 2-2 and 2-3). Further discussions about USACE project planning, authorization, and appropriations process are provided later in this chapter.

TABLE 2-2 Coastal and Inland Flood and Storm Damage Components of USACE Civil Works Budget Appropriations (millions of dollars)

| FY 2008 | FY 2009 | FY 2010 | FY 2011 | FY 2012 | |

| Coastal flooding and storm damage reduction | |||||

|

Construction |

52 | 58 | 59 | 131 | 60 |

|

Operations and maintenance |

16 | 2 | 0 | 58 | 8 |

|

Investigations and other |

5 | 4 | 11 | 18 | 11 |

| Total coastal flooding and storm damage reduction | 73 | 64 | 70 | 207 | 79 |

| Total Inland flooding and storm damage reduction | 1,662 | 1,514 | 1,796 | 1,585 | 1,346 |

| Total USACE Civil Works budget | 5,591 | 5,210 | 5,449 | 5,055 | 5,003 |

SOURCE: B. Carlson, USACE, personal communication (2013).

TABLE 2-3 Supplemental Funding for USACE Coastal Risk Reduction Projects Since FY 2005

| Supplemental | Storm Event Addressed | USACE Funding Appropriated (million $) |

| P.L. 109-62 (FY 2005) | Hurricane Katrina | 400 |

| P.L. 109-148 (FY 2006) | Hurricanes Katrina, Rita, Wilma, Ophelia | 2,361 |

| P.L. 109-234 (FY 2006) | Hurricanes Katrina, Rita | 3,653 |

| P.L. 110-28 (FY 2007) | Hurricanes Katrina, Rita | 1,433 |

| P.L. 110-252 (FY 2008-09) | Hurricane Katrina (+ recent storms) | At least 5,762 |

| P.L. 110-329 (FY 2008) | Hurricane Katrina (+ recent storms) | At least 1,500 |

| P.L. 111-32 (FY 2009) | Hurricane Katrina (+ recent storms) | At least 439 |

| P.L. 113-2 (FY 2013) | Hurricane Sandy | 5,081 |

| Total | At least 20,629a |

aAn additional $2 billion in supplemental funds were provided between FY 2008 and FY 2010 to address “recent storms,” which may or may not include other hurricane events.

SOURCE: B. Carlson, USACE, personal communication (2013).

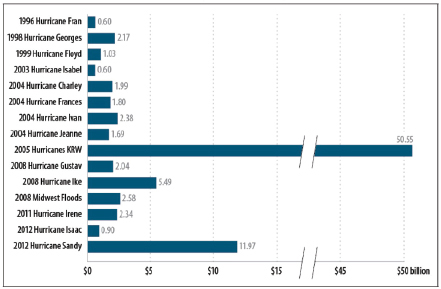

Federal Emergency Management Agency

FEMA authorities and responsibilities for coastal risk management activities range from direct response to natural disasters to oversight of mitigation programs to administration of the National Flood Insurance Program (see Box 2-2). Additionally, the Homeland Security Act of 2002 tasked the FEMA administrator to lead the nation in natural disaster preparedness, mitigation, response, and recovery. FEMA addresses all types of disasters, but in recent years coastal storm events represent the majority of FEMA’s largest disaster relief expenditures. Between 1996 and 2013, out of 15 disasters with FEMA disaster expenditures of at least $500 million, 14 of those were hurricane events, and these major hurricane-related expenditures represented 75 percent of all of FEMA’s Disaster Relief Fund expenditures over this period (Figure 2-1; Lindsay, 2014). The following sections briefly summarize the major FEMA programs in the areas of response and recovery, mitigation, and flood insurance. The funding reported for FEMA programs (Table 2-4) is not specific to coastal risk management.

Response and Recovery

After a disaster, FEMA may assist with initial damage assessments and assists in coordinating federal, state, and local response efforts. FEMA also manages several programs to support recovery after a federal disaster declaration.

BOX 2-2

Major FEMA Authorities Related to Coastal Risk Reduction

- National Flood Insurance Act of 1968 (P.L. 90-448)—Created the Federal Insurance Administration and made flood insurance available.

- Flood Disaster Protection Act of 1973 (P.L. 93-234)—Made the purchase of flood insurance mandatory for properties located in special flood hazard areas (the 1 percent chance [or 100-year] floodplain).

- Robert T. Stafford Disaster Relief and Emergency Assistance Act of 1974 (P.L. 93-288, amended in 1988 by P.L. 100-707)—Outlines the means by which the federal government works with local, state, and tribal governments to provide emergency assistance after a disaster.

- Disaster Mitigation Act of 2000 (P.L. 106-390)—Provided the legal basis for FEMA mitigation planning requirements associated with eligibility for pre- or post-disaster mitigation and recovery funds. The Act encourages a more proactive approach to risk mitigation by incentivizing comprehensive and integrated hazard mitigation planning.

- Homeland Security Act of 2002 (P.L. 107-296)—Assigned responsibility to the FEMA administrator to “lead the Nation’s efforts to prepare for, protect against, respond to, recover from, and mitigate against the risk of natural disasters, acts of terrorism, and other manmade disasters, including catastrophic incidents; … [and] develop and coordinate the implementation of a risk-based, all-hazards strategy for preparedness.”

These laws recognize the national interest in disaster prevention and mitigation and provide funding for that purpose, but they also recognize that risk reduction measures need to be coordinated with and, in many cases, undertaken by local communities.

Public Assistance. The Public Assistance Program provides funding to state, tribal, or local governments to repair damaged infrastructure and for debris removal. The program provides at least 75 percent of the costs of eligible projects. Infrastructure is often repaired to pre-flood conditions, unless an effort is made to include mitigation for risk reduction, which would require a benefit-cost analysis.1

Individual Assistance. The Individual Assistance Program provides disaster aid directly to individuals, including temporary housing or funding for housing repairs, crisis counseling, and grants to assist with needs not covered by insurance, such as transportation, medical, or funeral expenses.2

______________

1See http://www.fema.gov/public-assistance-frequently-asked-questions.

2See http://www.fema.gov/disaster-process-disaster-aid-programs.

FIGURE 2-1 Disasters between 1996 and 2013 with FEMA expenditures greater than $500 million (actual-year dollars). Amounts reflect FEMA disaster assistance expenditures as of February 2013, and do not included funding provided by other agencies. KRW = Katrina, Rita, and Wilma.

SOURCE: Lindsay (2014).

TABLE 2-4 Components of FEMA Budget Appropriations, including Emergency Supplemental Appropriations (in millions of dollars).

| FY2008 | FY2009 | FY2010 | FY2011 | FY2012 | FY2013 | |

| Disaster Assistance Direct Loan Program | ||||||

|

Annual Appropriation |

0.875 | 0.295 | 0.295 | 0.294 | 0.295 | 0.27 |

|

Emergency Supplemental |

98.2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 300 |

| Disaster Relief Funda | ||||||

|

Annual Appropriation |

1,324 | 1,288 | 1,600 | 2,523 | 7,076 | 6,653 |

|

Emergency Supplemental |

10,960 | 0 | 5,100 | 0 | 6,400 | 10,914b |

| Mitigation | ||||||

|

Pre-Disaster Mitigation |

114 | 90 | 100 | 50 | 36 | 24 |

|

Flood-related Grantsc |

62 | 110 | 79 | 209 | 60 | 120 |

NOTE: Funding shown here addresses all disasters, not just coastal storms.

aUp to 15 percent of Disaster Relief Funds may be spent through the Hazard Mitigation Grant Program.

bAfter sequestration.

cIncludes the three NFIP mitigation grant programs: the Flood Mitigation Assistance, Repetitive Flood Claims, and Severe Repetitive Loss programs.

SOURCES: DHS (2009a,b, 2010a,b, 2011a,b, 2012b,c, 2013d,e, 2014a,b); Brown (2012), Lindsay (2014).

In FY 2012, the award range was $50-$31,400, with an average award of $2,982.3

The Public and Individual Assistance Programs are funded through the Disaster Relief Fund, which receives annual appropriations and emergency supplemental appropriations as needed. For example, the Hurricane Sandy Supplemental (P.L. 113-2) provided $11.5 billion (before sequestration) for the Disaster Relief Fund (Table 2-1). In response to Hurricane Katrina, $43.1 billion was provided for the Disaster Relief Fund in FY 2005 via supplemental funding (Lindsay and Murray, 2011). Funding for the Disaster Relief Fund since 2008 is shown in Table 2-4.

Community Disaster Loans. The Community Disaster Loan program, funded through the Disaster Assistance Direct Loan Program (see Table 2-4), offers low-interest loans to local governments to maintain government functions after a substantial loss of revenue. Under certain conditions of continuing financial hardship, FEMA is permitted to cancel repayment of loans 3 years after the disaster. Brown (2012) reports that FEMA has forgiven $896 million of the $1,326 million loaned to local governments since the program began in 1974.

Mitigation

FEMA has three major programs that provide grants for mitigation efforts: Pre-Disaster Mitigation, the Hazard Mitigation Grant Program, and Flood Mitigation Assistance.

Pre-Disaster Mitigation. The Pre-Disaster Mitigation program is used to fund local, state, and tribal governments and others at the community level to plan for hazards and implement cost-effective risk reduction measures prior to a disaster. The Pre-Disaster Mitigation program provides up to 75 percent of the costs of mitigation activities (or up to 90 percent in small or low-income communities), and the projects are funded through a competitive process (CBO, 2007).4 Annual appropriations for the Pre-Disaster Mitigation program have ranged from $24 million to $114 million since 2008 (see Table 2-4).

Hazard Mitigation Grants. The Hazard Mitigation Grant Program has provided funds to states after a Presidential disaster declaration to reduce

______________

4Individual homeowners or businesses are not permitted to apply for funds in this program, although local governments or nonprofits may apply on their behalf. See http://www.fema.gov/pre-disaster-mitigation-grant-program.

or eliminate losses in future disasters. The states then allocate the funds to state and local governments, tribes, and nonprofits for hazard mitigation. Up to 15 percent of total disaster funding for each state may be provided through the Hazard Mitigation Grant Program. At least 25 percent of the costs of eligible mitigation projects must be provided by state or local governments, although funds from the Housing and Urban Development Community Development Block Grants (see discussion below) can be used as the nonfederal cost share.5 The Hazard Mitigation Grant Program is funded through the Disaster Relief Fund, discussed in the preceding section. Hazard mitigation grants were about 5 percent ($5.2 billion; DHS, 2012a) of disaster relief funds between 2004 and 2012, which totaled over $100 billion (Lindsay, 2014).

Flood-related Grants. The National Flood Insurance Program provides grants through three programs—the Flood Mitigation Assistance, Repetitive Flood Claims, and Severe Repetitive Loss programs—to support mitigation efforts that would reduce the program’s future losses. The programs provide funds to state and local governments to support mitigation planning and mitigation projects for structures with repetitive losses that are insured under the National Flood Insurance Program. Recent appropriations have ranged from $60 million to $209 million (Table 2-4).

National Flood Insurance Program

The National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP) was established by the National Flood Insurance Act of 1968 as a means to encourage community level actions to reduce flood losses and to provide insurance to property owners already at risk of flooding in communities that adhere to floodplain standards. As a condition for participation in the program, local governments agree to adopt and enforce construction standards to reduce potential damage to new or substantially improved buildings in “special flood hazard areas”—the land surface area covered by a 1 percent annual chance (100-year) flood (see Box 1-3).

As of December 2012, the NFIP had over 5.5 million policies in over 21,000 communities in the United States (NRC, 2013). Approximately 19 percent of all policies are discounted—most because the structures were built prior to the development of flood risk maps, and thus received subsidized rates (ASFPM, 2013). The NFIP was not structured to hold sufficient funds for eventual heavy flood losses. Instead, the program was given limited borrowing authority from the federal treasury so insured claims could be paid when losses exceeded premium income (which is set

______________

5See http://www.fema.gov/hazard-mitigation-grant-programs-frequently-ask-questions.

to cover the average historical loss year; NRC, 2013). Annual operating losses (premiums minus claims and operating expenses) occurred in many years during the 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s (Michel-Kerjan, 2010), and the NFIP borrowed money periodically but was always able to pay back what it borrowed until 2005, when four major hurricanes hit. The losses from that year (nearly $19 billion) exceeded the total losses of the program since its inception. As of 2013, the debt stood at $30.4 billion (King, 2013). To the degree the program fails to adequately reflect risk in rates and operates at a loss, it has been subsidizing the occupancy of hazardous areas.

In July 2012 the National Flood Insurance Reform Act, known as the Biggert-Waters Act, was passed by Congress and signed into law (P.L. 112-141). The Act phased out subsidized insurance for many of the properties insured under the NFIP, including repetitive loss properties, second homes, businesses, and those that had “grandfathered” rates after a flood risk map update. Under the Act, actuarially based rates would be in effect immediately if a policy lapsed or the residence was sold. These changes mandated by the Biggert-Waters Act would have led to significant rate increases for the approximately 1.1 million NFIP policyholders with subsidized rates.

In response to substantial public outcry over the significant impact of Biggert-Waters on insurance rates and potential impact on property values, Congress adopted the Homeowner Flood Insurance Affordability Act of 2014 (P.L. 113-89), which reinstated discounted rates and repealed the large increase in rates with property sales or lapsed policies. Discounted rates will be increased gradually (up to 18 percent annually for primary residences and up to 25 percent annually for businesses, nonprimary residences, and repetitive loss properties) for all properties until the premiums reach full risk-based rates. The new law also allows for rate adjustments for flood mitigation actions that are not part of the insured structure and implements a surcharge on all policyholders ($25 for primary residences, $250 for all other policies).

In support of the NFIP, FEMA develops and updates flood insurance rate maps (FIRMs), which delineate floodplains with 1 percent and 0.2 percent annual chance of flooding (100- and 500-year floods) and are critical for local and regional planning. FIRMs in many communities are out of date, but FEMA is in the process of updating its rate maps to include high-accuracy, high-resolution topographic data available from current technologies and to reflect recent land-use changes (e.g., NRC, 2009). The current national percentage for new, validated, or updated engineering FIRMs is approximately 64 percent (Paul Rooney, FEMA, personal communication, 2014). FEMA flood rate maps only reflect today’s risks and do not forecast the flooding implications of climate change and sea-level rise. However, FEMA was tasked in the Biggert-Waters Act to establish

a Technical Mapping Advisory Council to develop recommendations for incorporating climate change science into flood risk assessments.

Department of Housing and Urban Development

HUD coordinates the Community Development Block Grants (CDBG) program, which provides economic development funding for state, local, and tribal governments. Among the program’s priorities is funding projects for disaster recovery assistance, especially for low- and moderate-income communities. Disaster Recovery grants can assist with housing buyouts and relocation to safer areas, house repair or replacement, and construction of public infrastructure. As noted previously in this section, these funds can be used as the nonfederal cost-share for the Hazard Mitigation Grant Program. In FY 2013, Congress appropriated $16 billion ($15.2 after sequester) to the CDBG (Table 2-1). The program received appropriations of $16.7 billion in FY 2006 in response to Hurricanes Katrina, Rita, and Wilma and $6.1 billion in FY 2008 for disasters including Hurricanes Ike, Dolly, and Gustav.6 Although HUD encourages CDGB rebuilding efforts to incorporate preparedness and mitigation, there is no explicit requirement to do so. Of the $1.8 billion in CDBG funds for New York City, approximately $533 million was targeted to enhance disaster resilience (NYC, 2013).

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration

NOAA is charged “to advance ocean, coastal, Great Lakes, and atmospheric research and development” (33 USC § 893). Its contributions to coastal risk reduction come from observational data collection and forecasts, inundation modeling and risk reduction decision support tools, coastal zone management, and training. Under the Coastal Zone Management Act of 1972, NOAA administers the Coastal Zone Management Program, which is a partnership between states and NOAA to manage coastal resources, including conservation, recreation, and development. NOAA also administers the Coastal and Estuarine Land Conservation Program, which has a goal of protecting coastal or estuarine areas that have conservation or ecological value.

NOAA research and data collection provide important support for coastal risk management at local, state, and federal levels. Observations of water level, topography and bathymetry, and aero-gravity data are used to create National Weather Service storm surge forecasts and will

______________

6See http://portal.hud.gov/hudportal/HUD?src=/program_offices/comm_planning/communitydevelopment/programs/drsi.

be used to create inundation maps. The Coastal Services Center supports a Sea Level Rise and Coastal Flooding Impacts Viewer, which is used to visualize future sea-level rise and potential impacts to coastal communities. This tool can also be used for redevelopment planning, especially to visualize the expansion of the flood hazard areas. Additionally, through the Digital Coast program,7 they provide access to physical, topographic, hazard, and social science data for the nation’s coasts.

NOAA’s National Ocean Service FY 2013 budget (under a continuing resolution) included $72 million for Coastal Science and Assessment and $114 million for Coastal Zone Management and Services and Coastal Management Grants (NOAA, 2013). The committee does not have information on what percentage of these budgets directly supports coastal risk reduction.

Other Federal Programs

As illustrated in Table 2-1, the federal government provides substantial post-disaster recovery funds to redress the impact of coastal storms on public and private infrastructure through the Small Business Administration, Department of Transportation, Department of Agriculture, Environmental Protection Agency, and other agencies. Additionally, the federal government supports mapping, data collection, tool development, and research to enhance coastal risk management through agencies such as the U.S. Geological Survey, while the Environmental Protection Agency is working to enhance the resiliency of water infrastructure. Some of the key agencies are discussed briefly below.

Small Business Administration (SBA)

The SBA manages the Disaster Loan Program, which can be used for repair or replacement of personal and business property. The low-interest loans are available to homeowners, renters, and businesses and can be used to cover uninsured losses to personal property, including homes, vehicles, and clothing. Additional funding (up to 20 percent of the amount of disaster damage, not to exceed $200,000) can be made available for mitigation measures, such as elevating a home.8 The Hurricane Sandy Emergency Supplemental Appropriation (P.S. 113-2) included $779 million for the Disaster Loan Program Account.

______________

Department of Transportation

The Department of Transportation has several major efforts under way with application to coastal risk reduction. The Federal Highway Administration is working to test strategies for assessing transportation infrastructure vulnerabilities to climate change and extreme weather and for improving infrastructure resilience. Additionally, the Federal Transit Administration received Hurricane Sandy Emergency Supplemental Appropriations of $10.8 billion to repair the most impacted transit systems (P.L. 113-2), and as of June 2013, the FTA had allocated $1.3 billion toward mitigation efforts that would enhance the resiliency of transit systems in the region to future disasters (Executive Office of the President, 2013).

U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA)

USDA’s Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) manages several programs to assist landowners after a natural disaster. The Emergency Conservation Program (ECP) provides assistance to restore agricultural land to a productive state after a natural disaster, and the Emergency Forest Restoration Program (EFRP) provides assistance to private, nonindustrial forestland owners to address damage on those lands. The Emergency Watershed Protection (EWP) program supports emergency recovery efforts to prevent erosion and reduce runoff, such as removing debris from clogged stream channels or restoring undermined stream banks.9 These programs are funded only in response to disasters, and receive no annual appropriations. In response to Hurricane Sandy, Congress appropriated $15 million to the ECP, $23 million to the EFRP, and $180 million to the EWP (Painter and Brown, 2013).

Department of the Interior

U.S. Geological Survey (USGS). Coastal risk- and coastal change-relevant activities are spread broadly across the USGS. USGS mapping programs provide geospatial information including coastal elevation, hydrography, geology, and land cover and land use. Monitoring from the USGS Water Mission Area includes real-time and post-storm observations of storm surge and high water levels and, with national monitoring of riverine flows and water levels, supports forecasts and assessments of coastal inundation hazards. The Ecosystems Mission Area conducts research on the health and vulnerability of coastal wetlands, forests, coral reefs, and species and populations of ecological and commercial concern. The Natural Hazards

______________

9See http://www.nrcs.usda.gov/wps/portal/nrcs/main/national/programs/landscape/ewpp/.

Mission Area provides tools that can anticipate and respond to hazards, vulnerability, and risk.

The Coastal and Marine Geology Program (CMGP) is conducting a National Assessment of Coastal Change Hazards over multiple timescales, considering hurricanes and extreme storms, long-term shoreline change, sea-level rise, and seacliff erosion. A Web-based portal is being developed to provide access to data, tools, and assessment products for coastal managers and stakeholders. As part of its broad research effort, the CMGP also supports the development of sediment transport models and research on fundamental coastal processes, including regional research studies to provide the process-level understanding necessary to forecast the evolution of coastal systems (e.g., Fire Island, New York; Gulf Barrier Islands, Louisiana and Mississippi). Funding for CMGP base activities, which support coastal change hazards research and products, averaged $13 million per year over the past 5 years (FY 2009-FY 2013) (J. Haines, USGS, personal communication, 2014). In FY 2013, the USGS received emergency supplemental appropriations totaling $41.2 million, including $16 million for the CMGP to enhance data collection, expand vulnerability assessments, conduct regional studies including geological mapping and oceanographic modeling, and to improve the delivery of data, tools, and products (P.L. 113-2).

Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS). The Coastal Barrier Resources Act, enacted in 1982 and reauthorized in the Coastal Barrier Reauthorization Act of 2000, designated relatively undeveloped barriers along the Gulf and Atlantic Coasts, including both private and public lands, as part of the John H. Chafee Coastal Barrier Resources System (CBRS). The Act “encourages the conservation of hurricane prone, biologically rich coastal barriers by restricting Federal expenditures that encourage development,”10 including federal flood insurance, loans by the Small Business Administration, and subsidies for erosion control, utilities, roads, and bridges. All costs of new development on these lands must be borne by nonfederal parties, although federal funds are still permitted to aid in disaster recovery after a major storm (Salvesen, 2005). The FWS is responsible for administering the Act and estimates that the program saved the federal government over $1 billion between 1982 and 2010. GAO (2007) estimated that 16 percent of the CBRS lands experienced development in spite of the federal funding restrictions, encouraged by strong real estate market pressures, the availability of private insurance, and state and local land-use policies that promote floodplain development. The Department of the Interior is modernizing the maps of the CBRS in the north Atlantic with $5 million funding from the Hurricane Sandy emergency supplemental appropriation (P.L. 113-2).

______________

Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)

In addition to helping water and wastewater utilities recover from coastal disasters, EPA has several climate-based initiatives under way related to enhancing the resiliency of water and wastewater infrastructure through the Climate Ready Water Utilities program. EPA recently launched the Climate Resilience Evaluation and Awareness Tool to assist drinking-water and wastewater utility managers in understanding climate change threats, including flooding and extreme weather events, and available adaptive measures.

EPA also supports effective wetlands management through partnerships with state, local, and tribal governments and other stakeholders. EPA established a Coastal Wetlands Initiative to better understand factors related to coastal wetland loss and to protect and restore wetlands. In addition, EPA’s Climate Ready Estuaries Program analyzes areas for vulnerability to climate change and develops strategies for adaptation, in association with the National Estuary Program and coastal managers.

Federal Coordination Efforts

There are numerous executive and federal interagency policies that have been adopted to bridge the gaps between federal programs and provide better coordination of federal efforts. Even with these policies, it is recognized that federal agencies and their budgets remain guided primarily by their statutory missions.

The Hurricane Sandy Rebuilding Task Force was a focused effort to improve federal coordination and align federal resources with local recovery and rebuilding priorities. Led by HUD, with membership from more than 20 other federal departments, agencies, and offices, the Task Force made numerous policy recommendations, including a building elevation standard (advisory base flood elevation + 1 foot [0.3 m]) for rebuilding efforts using federal funds (Hurricane Sandy Rebuilding Task Force, 2013).

Many of the federal executive and interagency coordination efforts have been developed under the umbrella of an all-hazards approach, including terrorist acts as well as natural disasters. In response to a Presidential Policy Directive, PPD-8 (2011), a National Preparedness Goal11 was developed along with five supporting planning frameworks (focused on disaster prevention, protection, mitigation, response, and recovery; DHS, 2013a,b,c) to guide agencies and personnel to operate in a unified and

______________

11The following National Preparedness Goal was developed in 2011: “a secure and resilient nation with the capabilities required across the whole community to prevent, protect against, mitigate, respond to, and recover from the threats and hazards that pose the greatest risk.” See http://www.fema.gov/national-preparedness-goal.

collaborative manner in disaster-related efforts. The National Disaster Recovery Framework, while providing much-needed structure and principles to support coordination, does not attempt to reconcile sometimes differing individual program mandates or authorities. With regard to natural disasters, the framework largely emphasizes mitigation, response, and recovery, rather than addressing the removal of incentives that continue to permit and in some cases encourage development (and redevelopment) that places people and property in harm’s way.

Several federal coordination efforts address coastal risk management among other issues. The Federal Interagency Floodplain Management Task Force was authorized by Congress and established under the Water Resources Council in 1975 to develop a proposed framework for a “Unified National Program for Floodplain Management.” The Task Force, which consists of 12 federal agencies and is chaired by FEMA, has proposed several such frameworks (FIFMTF, 1986, 1989, 1994). It was reconvened in 2009 after a decade of inaction, and continues to work to unify federal programs on flooding, despite minimal impact of past reports. Recent efforts include guidance on unwise use of floodplains (FIFMTF, 2012) and consensus recommendations for actions by task force agencies and the task force itself to improve floodplain management (FIFMTF, 2013).

President Obama established the Interagency Climate Change Adaptation Task Force, co-chaired by the Council on Environmental Quality (CEQ), the Office of Science and Technology Policy, and NOAA, and including representatives from more than 20 federal agencies (ICCATF, 2011). In October 2009, President Obama signed Executive Order (E.O. 13514) directing the Task Force to recommend ways that federal policies and programs can better prepare the nation for climate change.

More recently, President Obama established an interagency Council on Climate Preparedness and Resilience in November 2013. Among its functions, the Council is tasked to “support regional, State, local, and tribal action to assess climate change related vulnerabilities and cost-effectively increase climate preparedness and resilience of communities, critical economic sectors, natural and built infrastructure, and natural resources” (E.O. 13653). The 2013 executive order also established a task force of state, local, and tribal leaders on climate preparedness and resilience to provide recommendations on “how the federal government can remove barriers, create incentives, and otherwise modernize Federal programs to encourage investments, practices and partnerships that facilitate increased resilience to climate impacts, including those associated with extreme weather.”

Other executive orders have been issued to coordinate federal actions and improve the consistency of policies shaping the efforts of federal agencies. For example, Executive Order 11988 (1977) required federal agencies to minimize actions that result in “adverse impacts associated with the

occupancy and modification of floodplains and to avoid direct or indirect support of floodplain development wherever there is a practicable alternative.” However, executive orders are not always implemented fully and consistently across all federal agencies.

USACE PROJECT PLANNING, AUTHORIZATION, AND FUNDING

The USACE is the primary agency that oversees the planning, design, and construction of projects such as hard structures and beach nourishment to reduce the probability of coastal hazards (e.g., flooding, wave attack). Thus, in addition to the prior discussions of agency responsibilities and budgets, it is important to understand the mechanisms by which USACE coastal risk reduction projects are identified, designed, authorized, and funded. This section summarizes the procedures and criteria that the USACE uses for coastal risk reduction project planning, authorization, and appropriations, in order to provide a context for understanding opportunities for and impediments to improving links with other federal, state, and community risk reduction efforts.

Project Initiation and Planning

Guidance for USACE water resources planning activities, including coastal risk reduction, inland flood risk reduction, navigation, and ecosystem restoration, comes from several sources, but the two most important that are currently in effect are the Economic and Environmental Principles and Guidelines for Water and Related Land Resources Implementation Studies (Principles and Guidelines; WRC, 1983) and the Planning Guidance Notebook (Engineering Regulation 1105-2-100; USACE, 2000a). The Principles and Guidelines provide federal agencies (e.g., USACE, the Bureau of Reclamation, the Tennessee Valley Authority) with detailed instructions for evaluating water-related project alternatives. 12 The Planning Guidance Notebook (USACE, 2000a) was developed to provide additional guidance within the USACE in implementing the Principles and Guidelines. Additional detailed USACE guidance specific to coastal risk reduction has also been developed (USACE, 2011a,b).

Coastal risk reduction efforts are typically initiated at the local level among a USACE district office, a community or local interest group, and a congressional delegation. If a need is identified, funds are appropriated for the USACE to study the project and determine whether it represents a federal interest. If a federal interest is determined and USACE headquarters

______________

12Principles and Guidelines replaced Principles and Standards (WRC, 1973), which served as water-related planning requirements for federal agencies.

approves, a more detailed feasibility study is initiated that includes coordination with state and local entities, public involvement, and development of an environmental impact statement. Feasibility studies for USACE water resources projects typically have each taken about 4.5 years and several million dollars to complete (NRC, 1999). However, USACE headquarters has recently emphasized faster planning through the “3×3×3” initiative, which required feasibility studies to be completed in no more than 3 years, with three levels of vertical team integration, for no more than $3 million (Walsh, 2012). Congress must appropriate half of the funding for the feasibility study, with the remaining funds coming from the local sponsor (NRC, 2004b).

USACE projects, including coastal risk reduction projects, follow six project planning steps identified in the Principles and Guidelines:

- Specify problems and opportunities.

- Inventory and forecast conditions.

- Formulate alternative plans.

- Evaluate effects of alternative plans.

- Compare alternative plans.

- Select recommended plan.

This planning process is well described in USACE (2000a) and NRC (2004b).

Benefit-cost analysis serves as the most important decision criterion in project planning (USACE, 2000a). In some cases, specific exceptions from cost-benefit formulation are mandated by Congress, as they were for New Orleans and the Mississippi coast rebuilding efforts.13 According to the Principles and Guidelines (WRC, 1983), the objective of water resources project planning “is to contribute to national economic development [NED] consistent with protecting the Nation’s environment….” Thus, projects are designed to maximize NED benefits relative to financial costs, while ensuring that the project does not cause unacceptable adverse environmental impacts. Additional project elements may be necessary to mitigate environmental impacts (USACE, 2011a). Other social effects are also evaluated, but this information rarely influences planning decisions (NRC, 2004b). Principles and Guidelines has long been criticized for its narrow focus and failure to factor nonmonetary environmental and social costs or benefits

______________

13Projects such as the New Orleans Hurricane Storm Damage and Risk Reduction System and the Mississippi Coastal Improvements Project were designed, based on direction from Congress, without benefit-cost analysis as a basis of decision. Congress directed the New Orleans HSDRRS to be built to provide flood protection against a 100-year storm, and no assessment of benefits versus costs was performed. The MSCIP considered the cost-effectiveness of project components but did not evaluate the design by the benefit-cost ratio.

in project planning and decision priorities, and in the Water Resources Development Act of 2007, Congress directed the administration to revise them. In March 2013, the White House Council on Environmental Quality released the updated Principles and Requirements for Federal Investment in Water Resources (CEQ, 2013), which significantly broadens federal interests in water resources projects by stating

Federal investments in water resources as a whole should strive to maximize public benefits, with appropriate consideration of costs. Public benefits encompass environmental, economic, and social goals, include monetary and non-monetary effects and allow for the consideration of both quantified and unquantified measures.

However, the 1983 Principles and Guidelines will not be replaced until 180 days after revisions are completed on the detailed interagency guidelines that are to accompany the Principles and Requirements. Congress has also prohibited the USACE from implementing the new Principles and Requirements (Explanatory Statement to P.L 113-76). The 1983 Principles and Guidelines and the 2013 revised Principles and Requirements are discussed further in Chapter 4.

USACE projects are considered “economically feasible” if the national economic development benefits exceed the costs. The major categories of NED benefits that are currently considered in USACE coastal risk reduction projects are (USACE, 2011a)

- reduction in physical damage (including structures, contents, infrastructure, agricultural crops, and land value),

- reduction in nonphysical damages (including income loss, emergency response costs, evacuation, temporary housing, and transportation delays), and

- other benefits, such as increased recreational use, incidental recreation benefits, and land enhancement.

Recreation benefits, however, cannot exceed more than 50 percent of the benefits required for project justification. The value of human lives and well-being is not assessed in current calculations of NED benefits. Although termed “national economic benefits,” the beneficiaries may be primarily local in distribution. The planning process performs a separate calculation of “regional economic benefits,” but this term encompasses benefits that are transferred from one location to another (i.e., businesses that relocate), and therefore are not net gains from a national perspective.

For coastal storm damage reduction projects, the USACE considers damages from inundation, wave attack, and erosion, and estimates damage prevented by project alternatives. The costs and benefits over a 50-year

period of analysis are compared against a scenario of the future without the project alternatives in place. According to current USACE planning guidance (USACE, 2011b), these future scenarios must consider three scenarios of sea-level rise. USACE planning teams also evaluate project alternatives on their economic efficiency, meaning that each increment of a project must produce benefits that exceed costs. Ultimately, the selected plan represents an optimization of the net benefits, both in the overall plan and considering increments of the project, while meeting requirements of completeness, effectiveness, efficiency, acceptability, and compliance with federal, state, and local regulations (USACE, 2011b). Thus, coastal risk reduction projects are not designed with a specific level of risk reduction in mind (such as the 1 percent chance [100-year] flood event, see Box 1-3), unless the project is congressionally mandated to do so.

Coastal risk reduction projects that have been constructed by the USACE represent a range of levels of risk reduction, including many beach nourishment and dune construction projects that are built to prevent flooding from storms that have a 3 to 5 percent chance or greater of occurring in any given year (i.e., 20- to 30-year return interval; USACE, 2013c). This outcome is in marked contrast to inland flood risk reduction measures, which often are designed to reduce risks associated with a 1 percent annual-chance (100-year) event or larger for the purpose of alleviating flood insurance requirements for the residents behind the levees. Local sponsors, however, are required to fund the cost difference between the NED-justified design and the 1 percent chance risk reduction level, if the economic analysis does not justify risk reduction to a 1 percent chance event. USACE coastal risk reduction projects can also include measures to reduce the consequences of an event, such as land purchase and relocation, although several past reports have highlighted the USACE’s limited emphasis on such strategies (Moore and Moore, 1989; NRC, 1999, 2004b).

Once the preferred project alternative is identified, the USACE prepares a draft feasibility report and environmental impact statement. When finalized by the district office and after public comment and coordination with other federal agencies, the feasibility report is submitted to USACE Headquarters for approval.

Authorization and Appropriations

Following approval of the feasibility study by the Assistant Secretary of the Army (Civil Works) and a subsequent review by the Office of Management and Budget, the USACE feasibility study may be transmitted to Congress for authorization. Water Resources Development Acts (WRDAs) are typically used to authorize water resources projects, although WRDAs have been passed infrequently in recent years—the last three were passed

in 2000, 2007, and 2014. Only after authorization can projects be considered for federal appropriations for the federal portion of the projects (see Box 2-3), and funding is not guaranteed. The USACE Civil Works has a backlog of approximately 1,000 projects (including coastal risk reduction projects and other projects, such as navigation, dam and levee safety, and ecosystem restoration) that are authorized but unfunded, representing

BOX 2-3

Cost Sharing for Coastal Risk Reduction

The rules for cost sharing for traditional USACE coastal risk reduction projects vary among the types of USACE projects (Table 2-3-1). Accordingly, the federal government funds 50-65 percent of the construction of most USACE coastal risk reduction projects. However, Congress has provided greater federal funding for the construction of some risk reduction projects after a major disaster (e.g., 100 percent for construction and repair of authorized projects after Hurricane Sandy, 89 percent for the HSDRRS after Hurricane Katrina [USACE, 2012b]). Coastal risk reduction projects that involve beach nourishment are considered continuing construction projects, and thus maintenance costs are shared for the life span of the project. However, for other projects, such as for seawalls or levees, the nonfederal partner is responsible for 100 percent of the operations and maintenance costs. For example, in New Orleans, nonfederal funding is expected to pay for all maintenance costs once the project has been officially completed, even though subsequent “lifts” clearly will be needed to keep the levee heights at their design levels.

TABLE 2-3-1 Cost Sharing Percentages for Various Coastal Risk Reduction Project Scenarios

| Project Type | Federal Construction | Nonfederal Construction | Federal O&M |

| Federal shores | 100 | 0 | 100 |

| Public or private developed shores with public use | 65 | 35 | 0a |

| Undeveloped nonfederal public shores | 50 | 50 | 0a |

| Private developed shores, with private use | 0 | 100 | 0 |

| Undeveloped private lands | 0 | 100 | 0 |

aBeach nourishment is considered a continuing construction project, so all renourishment activity costs are shared according to the construction percentages.

SOURCE: Data from USACE (2000a).

about $60 billion (NRC, 2011b; Carter and Stern, 2013). Although positive net benefits are required for project authorization, the benefit-cost ratio used for budgetary prioritization often needs to be above 2.5 to compete for available funds in the President’s budget (USACE, 2013g). As discussed previously in this chapter, over 95 percent of USACE funding for coastal risk reduction projects (FY 2008–FY 2012) has also been allocated through separate emergency supplemental appropriations (Tables 2-2 and 2-3).

Supplemental funding provides both advantages and constraints for coastal risk reduction projects. Supplemental post-disaster funds can spur more holistic evaluations and regional perspectives for coastal risk reduction. For example, the New Orleans HSDRRS project was systematically developed for risk reduction and includes a combination of structures that protect the entire region from flooding (USACE, 2013b). Previously, the city’s flood risk reduction measures consisted of a series of smaller projects constructed over more than 50 years—“a system in name only” (IPET, 2009). The Mississippi Coastal Improvements Project is another example of a regional study funded by congressional mandate after Hurricane Katrina (USACE, 2009). In the area affected by Hurricane Sandy, the emergency appropriations allow previously authorized but unfunded projects to be constructed and existing projects to be restored to their design level. Key risks remain, however, because the projects being restored were originally designed and analyzed individually, rather than from a comprehensive, systemwide framework. The Sandy supplemental funding is also supporting the North Atlantic Comprehensive Study, which will provide a rare systemwide analysis of opportunities for coastal risk reduction. These regional studies and projects, which were funded at full federal expense, represent the exception rather than the norm for USACE coastal risk efforts. A major constraint of supplemental funding is that it tends to be reactive in nature, providing funding for risk reduction and resilience efforts only after an area has been impacted by a coastal storm. The funding provides little support for other areas of the nation at risk from future storms.

Challenges and Constraints Within the USACE Planning and Authorization Process

The USACE’s coastal risk reduction planning and design process, described in the preceding sections, has evolved over the last 50 years or so to meet changing needs and priorities within the United States. During this time, USACE activities were also expanded to include environmental restoration, and the cost of authorized projects to meet diverse USACE missions has far exceeded the appropriated funding. This section examines the adequacy of the existing USACE planning and authorization process to

address the nation’s increasing coastal risks from severe storms and rising sea levels.

Local Interests and Regional Planning

Although local engagement is essential in terms of ensuring that all work being considered is coordinated with local stakeholders, such interests often originate from relatively narrow segments of the at-risk area rather than the region as a whole. Within the current USACE planning process, it is far easier to consider individual projects within a specific geographic area that have a single purpose, such as beach nourishment, than to develop a comprehensive plan for coastal risk reduction. Regional comprehensive planning requires engagement of multiple local sponsors, each contributing to funding and planning a project beyond its jurisdiction. Such efforts require intense engagement and agreement among multiple local governments—some of which might not fare as well under a systemwide risk reduction effort as they might in a narrowly focused project. A comprehensive, regional coastal risk reduction project considering the full range of vulnerabilities (i.e., not just beach nourishment but also including back-bay flooding and urban areas) would take much longer to plan and could result in a project with a substantially higher cost. Comprehensive coastal risk reduction studies would also require specific authority and funding. Overall, these issues make it difficult to address coastal risk reduction on a regional scale within the USACE process.

Funding and Prioritization

Only a small fraction of annual USACE appropriations are directed toward coastal storm damage reduction projects (see Table 2-1), and competition for these funds is fierce. Instead, coastal risk is primarily addressed by the USACE via emergency supplemental funding after a disaster has occurred. As previously discussed, the result is that the nation is reactive to disasters, rather than proactive in addressing priorities at a national scale.

The nation also lacks a mechanism to weigh coastal risk reduction investments for large coastal cities from a national perspective. As noted in Chapter 1, eight large cities in the United States rank among the world’s top 20 in terms of estimated potential average annual losses from coastal flooding (Hallegatte et al., 2013) and numerous others face significant risks. Addressing coastal risks in densely developed urban areas requires extensive investments at systemwide scales, likely costing billions of dollars per city. In 2013, Mayor Bloomberg announced a plan to reduce New York City’s coastal risk costing at least $20 billion (NYC, 2013). Existing USACE annual appropriations are insufficient to address these challenges, and the

project-by-project authorization process does not allow the Congress to take stock of the nation’s coastal risks and plan a strategy to reduce them.

The capacity to support operations and maintenance of coastal risk reduction projects remains an additional challenge. Aside from beach nourishment projects, which are considered continuing construction projects for their life span, minimal funding is typically allocated for operations and maintenance of hard structural risk reduction projects (e.g., levees, surge barriers; see Table 2-1), because such funding is borne by local sponsors under current guidance. If localities are unable or unwilling to maintain existing coastal risk management projects to their original designs, local communities may be exposed to elevated risks and much lower benefits from the original federal investment.

STATE, LOCAL, AND NONGOVERNMENTAL RESPONSIBILITIES IN COASTAL RISK REDUCTION

As described above, most of the federal coastal risk reduction programs are designed to be implemented by or in collaboration with state and local governments that have primary responsibility and authority over planning, economic development, and land use. In addition, numerous reports have emphasized the importance of stronger private–public sector partnerships and community collaboration to strengthen community resilience and reduce risk (e.g., NRC 2001, 2010). States develop hazard mitigation plans to be eligible for FEMA pre- and post-disaster funding. Under the Disaster Mitigation Act (Box 2-2), states and localities support development of local mitigation plans and provide technical assistance to local governments. States administer FEMA’s Hazard Mitigation Grant Program and establish funding priorities consistent with their hazard mitigation plans. Local communities submit individual project applications to the state, coordinate with participating homeowners and businesses, and manage implementation of the approved projects.

State and local governments can implement building codes with minimum design and construction requirements that reduce the vulnerability of new structures in high-hazard areas. Model codes are usually developed and periodically revised by nongovernmental organizations (e.g., the International Code Council). Many but not all of the states affected by Hurricane Sandy have adopted the international building code and the international residential code. Based on a recommendation in the Hurricane Sandy Rebuilding Strategy (Hurricane Sandy Rebuilding Task Force, 2013), the Mitigation Framework Leadership Group (MitFLG) is currently working to encourage state, local, and private-sector adoption of the most recent (2012) version of these international model codes. Inconsistent adoption

or enforcement of codes at the state and local levels can leave communities vulnerable.

The Coastal Zone Management Act (CZMA) of 1972 (discussed above) provides a framework for federal-state cooperation on coastal hazard management, land use, and development. One of the main objectives of the CZMA is to “minimize the loss of life and property caused by improper development in flood-prone, storm surge, geological hazard, and erosion-prone areas and in areas likely to be affected by or vulnerable to sea level rise” (16 USC § 1452). With federal funding support and technical assistance under the CZMA, state and local governments develop coastal hazard management plans and conduct projects that address coastal hazards, such as revising construction setback regulations and mapping shorelines to identify high-risk erosion areas.

State and local governments can develop and implement their own plans for coastal risk reduction. The State of Louisiana’s Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority prepared its 2012 Coastal Master Plan to address the massive erosion of shorelines and wetlands that the state has experienced. The plan included hundreds of possible remedies for land loss and coastal risk reduction, including nonstructural measures, and called for extensive investment in coastal work in Louisiana for the next 50 years, with a total cost of $50 billion dollars (CPRA LA, 2012). State and local governments also partner with the USACE to develop and fund coastal risk reduction projects, per cost-sharing requirements (Box 2-3).

At the state and local levels, actions to consider risk reduction beyond that required by the programs described above have largely taken the form of adaptation plans. Examples include multisector climate adaptation plans in California (CNRA, 2009), a regional climate change compact in southeast Florida (SFRCCC, 2012), and ongoing development of state climate change adaptation plans in Maryland and Delaware. These plans have been informed by the recommendations of the federal Interagency Climate Change Adaptation Task Force (ICCATF, 2011). There are also numerous efforts in North Carolina and other states to map future shoreline change to evaluate how sea-level rise will impact flooding and risk management strategies (Burkett and Davidson, 2013). However, at the local level, it is challenging to maintain long-term climate change adaptation and resilience planning programs, although state and federal involvement can help sustain local efforts.

Nongovernmental organizations such as the Association of State Floodplain Managers and Coastal States Organization also provide policy recommendations that identify how federal efforts can better support state and local risk management and best practices for states. Other nongovernmen-

tal organizations such as The Nature Conservancy (along with federal, university, and private-sector partners) provide decision support tools for vulnerable coastal areas.14

ALLOCATION OF RISK, RESPONSIBILITY, REWARDS, AND RESOURCES

A major impediment to U.S. coastal hazard management is the misalignment of risks, rewards, responsibilities, and resources associated with coastal development and post-disaster recovery. If the risks, responsibilities, rewards, and resources are primarily borne by a limited number of agencies, as they are in the Netherlands, coastal risk management becomes more straightforward. However, in the United States, risks, rewards, responsibilities, and resources are each borne by different entities motivated by different objectives.

The rewards of coastal development flow to developers, engineers, architects, and builders, as well as local and state governments in the form of contracts, profits, and tax revenue. Rather than concluding simplistically that communities are acting recklessly in allowing development along the coast, it is important to recognize that local officials are acting rationally to the extent that development makes local economic sense, provides tax revenues, results in greater local employment and, in some cases, reflects the preservation of historical and cultural community values. It is ordinarily in the best interest of the property owner, developer, builder, and municipality to undertake construction regardless of future public risk and other externalities. Although local governments also bear some of the risk associated with storm damage to coastal development, other beneficiaries, such as developers and builders, evade such risks.

Risks associated with coastal development are borne by individual home and business owners (particularly those without flood insurance) and federal, state, and local governments (and their taxpayers) that fund disaster relief and recovery programs. Risks are also borne by coastal residents who face economic and social disruption after a severe coastal storm. However, behavioral and cognitive factors hinder individuals and organizations from taking appropriate risk reduction actions (Kunreuther, 2006). One limiting factor is the human tendency to be more accepting of risks associated with natural hazards (Slovic, 1987). Many people view natural hazard risks, especially those posed by low-probability/high-consequence events, as facts of life and acts of nature that are often inexplicable and cannot be completely avoided. The importance of risk reduction efforts is likely to be eclipsed, for both public officials and the general public, by

______________

more immediate and pressing concerns. The federal government also bears the risks of insuring flood losses through the National Flood Insurance Program, which offers discounted rates to some policyholders, contributing to the program’s $30 billion shortfall (King, 2013).

Responsibilities associated with sound land-use planning decisions fall primarily to local governments. Although the framework for U.S. emergency management provides that local communities are encouraged to mitigate, prepare for, and respond to disasters, in reality the incentives have been relatively weak. Behavioral research has shown that people are more likely to favor investments that generate immediate benefits than those that yield long-term benefits that accrue probabilistically (Kunreuther, 2006). Thus, it is generally much easier to elicit a sense of concern from public officials and the public for issues such as unemployment, economic development, crime, and traffic congestion, which affect the public almost daily. Meanwhile, localities depend on local tax revenues, enhanced by expanded development, to fund schools and other essential public services. The Stafford Act currently requires states and communities to develop and update hazard mitigation plans, but these plans are rarely incorporated into local economic development or land-use master plans.

Following major disasters, many look to the federal government for resources to fund emergency response, individual and community post-disaster assistance, redevelopment programs, mitigation efforts, and coastal storm damage reduction projects. In recent years, the federal government has borne a larger share of the costs associated with major hurricanes (Table 1-5). These efforts shift risk to federal taxpayers, thereby encouraging more intensive development and rebuilding in high-risk areas.

These government services may actually promote a phenomenon referred to as moral hazard (Mileti, 1999; Kunreuther, 2008). A moral hazard describes the possibility that individuals and organizations will take more risks when they believe that they will be protected from the consequences of their decisions. In the case of hazards, there is concern that individuals and local governments will continue to pursue floodplain development and avoid spending scarce resources on disaster preparedness and mitigation based on a belief that the federal government will bail them out (Platt et al., 2002). The Hurricane Sandy Emergency Supplemental Appropriations included little guidance or requirements that the expenditures would result in making communities, people, and property more resilient to future storms. Much of the $48 billion in funding (after sequester) was provided to support response or recovery programs at full federal expense, removing local and state funding requirements that can serve as disincentive to simply rebuilding regardless of long-term consequences. The U.S. Commission on Ocean Policy (2004) noted the need to coordinate the efforts of all coastal risk management agencies to reduce inappropriate incentives and

to “establish clear disincentives to building or rebuilding in coastal high-hazard zones.”

The lack of alignment of risk, reward, resources, and responsibility as it relates to coastal risk management leads to inefficiencies and inappropriate incentives that serve to increase the nation’s exposure to risk. Developers, builders, and state and local governments reap the rewards of coastal development but do not bear equivalent risk, because the federal government has borne an increasing share of the costs of coastal disasters. The resulting moral hazard leads to continued development and redevelopment in high-hazard areas.

Responsibilities for coastal risk reduction are spread over a number of federal, state, and local agencies, with no central leadership or unified vision. Multiple federal agencies play some role in coastal risk management, and each agency is driven by different objectives and authorities. No federal coordinating body exists with the singular focus of mitigating coastal risk, although several efforts are under way to increase coordination.

The vast majority of the funding for coastal risk-related issues is provided only after a disaster occurs, through emergency supplemental appropriations. Pre-disaster funding for mitigation, preparedness, and planning is limited, and virtually no attention has been given to prioritization of coastal risk reduction expenditures at a regional or national scale to better prepare for future disasters. Thus, efforts to date have been largely reactive and mostly focused on local risks, rather than proactive with a regional or national perspective. Also, although the federal government encourages improved community resilience, only a small fraction of post-disaster funds are specifically targeted toward mitigation efforts.

Few comprehensive regional evaluations of coastal risk have been performed, and the USACE has no existing institutional authority to address coastal risk at a regional or national scale. Given the enormous cost of coastal disasters within the United States, which are rising, improved systemwide coastal risk management is a critical need within the federal government. Under the current planning framework, the USACE responds to requests at a local level on a project-by-project basis, and several major urban areas remain at significant risk. Barriers effectively prohibit the USACE from undertaking a comprehensive national analysis of coastal risks and strategies to address them, unless specifically requested and funded by Congress.