Best Practices for Coordinated Response to an International CBRN Event

On March 11, 2011, the Tōhoku Earthquake (Great East Japan Earthquake) and subsequent tsunami caused a nuclear disaster at the Fukushima Daiichi power plant in Japan. In the wake of the disaster, Dr. Kiyoshi Kurokawa of the National Graduate Institute for Policy in Japan led an independent commission, The Fukushima Nuclear Accident Independent Investigation Commission, charged with investigating the Fukushima accident and providing recommendations to prevent future incidents. In the afternoon keynote presentation, Kurokawa reflected on his experience with the Daiichi commission, a first of its kind for Japan, and shared his perspective on the role and response of the Japanese government and other entities in the aftermath of the devastating disaster.

Opportunities and Challenges in Coordinating the Response to CBRN Events: Fukushima Daiichi, a Case Study

The speed and strength of the destruction from the Tōhoku Earthquake and subsequent tsunami provided a shock to the global community, offered Dr. Kiyoshi Kurokawa. Not only was the earthquake at 9.0 on the Richter scale, and resulting tsunami a record-breaking disaster, the event unfolded on television while the world watched. Kurokawa noted that people who witnessed the disaster first hand were able to disseminate information through social networks, which allowed for real-time reports of the disaster and its aftermath. This rapid information exchange also resulted in more direct scrutiny of the Japanese government’s response to the accident by the Japanese people and the world. In reaction to some miscommunication and mistrust that resulted during the response, an independent commission was formed and released a report, The Fukushima Nuclear Accident Independent Investigation Commission (2012). The primary mission of the commission was to investigate:

- Direct and indirect causes of the accident independent from political influences;

- Responses, damages, sequence of events, and actions taken and their effectiveness;

- History of decisions and approval processes regarding nuclear energy policies; and

- Recommend measures to prevent future nuclear accidents.

The investigation included the history of decision making and the approval process for nuclear power and policies going back to the 1950s, all with the goal of preventing future nuclear accidents (see Box 2.1 for the complete commission charge). The Commission did not address issues around future energy policy, damage compensation, decommissioning processes/technology, and disposition of spent nuclear fuel rods.

BOX 2.1

Charge to The Fukushima Nuclear Accident Independent Investigation Commission

The Commission was charged by the Speaker and the President of the National Diet of Japan (Japanese government) to do the following:

- To investigate the direct and indirect causes of the Tokyo Electric Power Company Fukushima nuclear power plant accident that occurred on March 11, 2011 in conjunction with the Great East Japan Earthquake.

- To investigate the direct and indirect causes of the damage sustained from the above accident.

- To investigate and verify the emergency response to both the accident and the consequential damage; to verify the sequence of events and actions taken; and to assess the effectiveness of the emergency response.

- To investigate the history of decisions and approval processes regarding existing nuclear policies and other related matters.

- To recommend measures to prevent nuclear accidents and any consequential damage based on the finding of the above investigations. The recommendations shall include assessments of essential nuclear policies and the structure of related administrative organizations.

- To conduct the necessary administrative functions necessary for carrying out the above activities.

Kurokawa explained that the Commission’s work was structured around 20 meetings with 38 key people in attendance, including the Prime Minister, Chief Cabinet Secretary, the Minister of Economy, Trade and Industry, and three former and current Heads of the Nuclear Safety Agency in Japan. The investigation included site visits to nine nuclear power plants that included the Fukushima Daiichi, Fukushima Daini, Tohoku Electric Power Company Onagawa Nuclear Power Plant, and The Japan Atomic Power Company Tokai Daini Power Plant. The Commission also visited Washington D.C., the GE Nuclear Headquarters in North Carolina, and the Nuclear Regulatory Commission Technical Training Center in Tennessee. In collecting evidence for the report, Kurokawa indicated that the commission held 900 hours of hearings with

over 1,000 people; conducted an evacuee’s survey with over 10,000 people participating, an on-site worker’s survey with over 2,000 participants, and town meetings with over 400 attendees. Kurokawa highlighted that key to the investigation was that all Commission meetings were broadcast live and available online with simultaneous English translation.

The report, The Fukushima Nuclear Accident Independent Investigation Commission (2012), resulted in nine conclusions and seven specific recommendations6 made to the legislative arm of the Japanese government. Kurokawa stressed that three key features of the investigation were very important to the final report; the process was transparent, secure, and open to the Japanese public and the world. Of the nine conclusions, Dr. Kurokawa emphasized the importance of number nine in which the Commission concluded a need to reform Japanese laws and regulations so that they are compatible with global standards, which had not previously been implemented in Japan. The seven recommendations by the Commission7 included:

- Monitoring of the nuclear regulatory body by the National Diet

- Reform the crisis management system

- Government responsibility for public health and welfare

- Monitoring the operators

- Criteria for the new regulatory body

- Reforming laws related to nuclear energy

- Develop a system of independent investigation commissions

Of these recommendations, Dr. Kurokawa pointed to the importance of the first recommendation, which focused on monitoring by the National Diet and the need to establish “a permanent committee to deal with issues regarding nuclear power…in order to supervise the regulators to secure the safety of the public” (The Fukushima Nuclear Accident Independent Investigation Commission, 2012).

Kurokawa shifted the discussion to the lessons learned from his work with the Commission. He emphasized the importance of not forgetting the devastation that occurs in the wake of a “black swan” event,8 and stressed that transparency in preparing for and responding to an event like Fukushima is the foundation for public trust. Kurokowa offered that the increasing interconnectivity of the world leads to more global risks, and noted the importance of working across siloes and building resilience through “anticipatory strategy” based on shared knowledge.

Kurokawa concluded by addressing the need to increase resilience between partner nations and to harness the power of new technologies and individuals who are working to solve the complex issues that arise with catastrophic events. He raised the need for a “global exchange

_______________

6 For detailed information on the nine conclusions made by the Fukushima Nuclear Accident Independent Investigation Commission, please see pages 16–21 in the Executive Summary of the official report at http://www.nirs.org/fukushimawarp.da.ndl.go.jp/info:ndljp/pid/3856371/naiic.go.jp/wpcontent/uploads/2012/09/NAIIC_report_lo_res10.pdf.

7 For the complete versions of the seven recommendations of the Fukushima Nuclear Accident Independent Investigation Commission, please see pages 22–23 in the Executive Summary of the official report at http://www.nirs.org/fukushima/naiic_report.pdf; http://warp.da.ndl.go.jp/info:ndljp/pid/3856371/naiic.go.jp/wpcontent/uploads/2012/09/NAIIC_report_lo_res10.pdf.

8 A black swan event is one that is characterized by being rare and unpredictable, with massive consequences. Most recently, this term was explored in two books by Nassim Nicholas Taleb, Fooled by Randomness: The Hidden Role of Chance in Life and in the Markets (2001), and a more in depth examination in his follow-up book, The Black Swan Theory: The Impact of the Highly Improbable (2007).

program” between nuclear regulators and operators that promote information sharing based on actual experience, similar to how scientists facilitate research and information exchange through peer reviewed journals. He also emphasized the need to develop global nuclear standards and licensing, along with common lines of communicating that information, so that every nation has a common resource that can help increase national security and safety. Finally, Kurokawa proposed that the Japanese government should invite continued comment, analysis, and input from world experts as they continue to recover from the Fukushima accident, and to keep the input and decision-making processes transparent as part of good governance; it is very important to share all of this information because “something similar could happen next week” anywhere in the world.

Best Practices for Coordinated Response to International CBRN Events

Moderator, Ann Lesperance of the Pacific Northwest National Laboratory indicated that the panel would focus on best practices for coordinating international response efforts by showcasing actual events, such as the Fukushima accident. The panel was framed around two questions; a) what are best practices for effective response to CBRN events in partner nations, and b) what are examples of successful coordinated response efforts? What are the challenges? Panelists included Dan Blumenthal of the Department of Energy, Charles Donnell of the American Red Cross, Colonel Patrick Terrell from the Department of Defense, and Brent Woodworth of the Los Angeles Emergency Preparedness Foundation.

The Role of the National Nuclear Security Administration of the Department of Energy in an International CBRN Event

The primary role of the National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA) of the Department of Energy (DOE) in a radiological disaster is to provide technical response for radiological and nuclear incidents, whether they occur domestically or internationally. Dr. Dan Blumenthal, NNSA Consequence Management Program Manager for the Office of Emergency Response at the Department of Energy, drew upon his experience in the response to the Fukushima accident in Japan to illustrate how NNSA capabilities are applied following a radiological event. Blumenthal stated that coordination and execution of response activities could be very different if an incident takes place in the United States versus another country. He framed the discussion around two main themes, the technical response to the incident and the importance of coordination and building relationships between all responding entities.

NNSA consequence management provides three primary technical capabilities for response after a radiological event, noted Blumenthal: monitoring, modeling, and medical management. Radiological monitoring is a central DOE capability and the service can be deployed in several ways; as standard ground-based monitoring, people carrying meters in the field, or specialized equipment outfitted for military and other aircraft. Modeling helps responders understand the likely spread of radiological material based on conditions at the time of an incident. Medical management experts advise and train responders on how to deal with

radiological injuries, exposure, and contamination. Teams collect raw data from the field, analyze the results, and translate the information in a way that supports critical decision making to help save lives and stabilize an area as quickly as possible. Blumenthal explained that small, interdisciplinary field teams work with DOE headquarters and laboratories to determine which course of action is the most appropriate for the reality on the ground; the tools used at the site are specific to the unique situation. During the response to the Fukushima accident very little modeling was done due to the many unknowns. Teams relied heavily on monitoring and aerial capabilities, which proved to be the only way to collect timely information over large areas of complicated and inaccessible terrain without putting responders in harms way.

Blumenthal addressed technical challenges that often emerge with response to international events; such as how U.S. capabilities “plug in” to a foreign government’s response capabilities. In the United States, DOE’s technical response activities fit with existing frameworks, such as the National Response Framework (Federal Emergency Management Agency, 2013), and response organizations. He cited Presidential Policy Directive 8 (White House and U.S. Department of Homeland Security, 2011), explaining that NNSA’s work spans the space of ‘prevent, protect, and respond’. In terms of FEMA’s core capabilities, the work supports situational assessment and environmental response, and health and safety. With international response, clear frameworks for partnering with other U.S. agencies and with international governments and organizations are rarely in place, and therefore it is critical to be able to adapt and coordinate on site. In Japan, DOE teams were part of multiple efforts, including the USAID’s Disaster Assistance and Response Team and the U.S. military’s Operation Tomodachi, in which they worked together to conduct field monitoring for U.S. interests and the embassy; the DOE team also partnered directly with the Japanese government. Blumenthal cited another technical challenge as how to translate raw data collected from monitoring activities into actionable products for decision makers. The type of units used in providing information may come into question depending on who is requesting that information, for example, the U.S. military versus the Japanese government. These were the types of issues that came about on the scene.

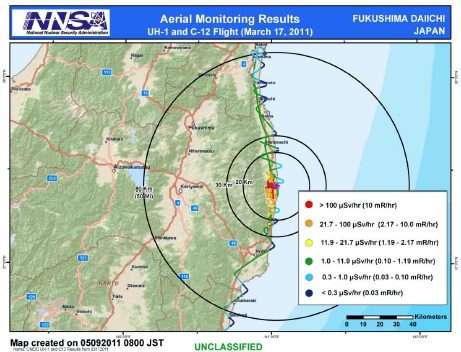

From the first day in Japan, DOE teams flew equipment with the U.S. military with the objective of mapping the radiation footprint that resulted from the Fukushima accident. Blumenthal noted that after three days, the scope of the incident was much better known (Figure 2.1). Although significant, teams discovered that the response did not require mass evacuations across Japan or that DOD personnel leave the area. Aerial surveys also collected information about areas that were not affected by the radiation plume. Compiling the data provided critical information for decision makers, and supporting communication for the public. Due to success of the monitoring program, the Japanese government continued aerial flights to map the plume after U.S. assistance was completed.

The importance of building relationships and respecting cultural differences and processes are also key capabilities for responding to an international CBRN event. Blumenthal noted that many federal agencies engage in outreach activities and capacity building with other nations, but cautioned there is a limit to what can be accomplished in advance of an event. Blumenthal explained that once a crisis occurs there is often a need to balance U.S. capabilities to provide assistance to a foreign nation with protecting U.S. citizens and interests in the region. In Japan, the U.S. response proved to be a combination of both.

Figure 2.1: Results of the initial aerial radiological survey to measure the exposure rate at ground level resulting from radioactive material deposited on the ground following the Fukushima accident. Source: U.S. Department of Energy/National Nuclear Security Administration (2011).

Upon arrival in Japan, building relationships became the most important process for working with the Japanese government on the response, Blumenthal said. What made the relationships work was transparency in how missions were conducted, and scientific integrity. Equally as important was respecting cultural differences and processes (see Box 2.2). In partnership with the military, DOE provided both the technical capability and the military infrastructure to assist their Japanese counterparts with logistics and aerial support. Over time, relationships developed between U.S. and Japanese technical teams at the Ministry of Education, Science, Culture, and Technology (MEXT). Blumenthal described how U.S. teams shared information with Japanese counterparts during high-level, formal meetings set up between the Department of State (DOS) and the Japanese Ministry of Foreign Affairs. The “icebreaker” came through the exchange of technical information, Blumenthal offered, specifically as U.S. teams shared a map of the radiation footprint. DOE/military teams helped the Japanese to form equivalent partnerships between Japanese civilian technical experts and their military counterparts, and Japanese teams began to conduct their own aerial surveys to map the radiation. This was significant in that civilian/military partnerships rarely exist in Japan. Blumenthal stated that the lesson learned was not to assume normal diplomatic procedures or political barriers will be in effect during a time of crisis.

Blumenthal highlighted best practices that emerged out of the response to the Fukushima accident. It is essential to balance U.S. and host country needs. Transparency and scientific integrity are also critical to building relationships; NNSA teams remained focused on the technical work, were transparent about their plans, shared data, and framed results in basic physical units. In closing, Blumenthal reemphasized two important components of international response: 1) the U.S. government has the technical capabilities—information, scientific integrity,

transparency, and adaptability—but can be limited in its ability to plug into the response efforts of different countries; and 2) be prepared to encounter cultural and procedural differences.

BOX 2.2

Respecting Cultural Differences

After three weeks of joint aerial surveys, U.S. and Japanese teams mapped the radiation footprint that resulted from the Fukushima accident. Blumenthal described how building the joint team was a lesson learned in respecting the Japanese culture and operational processes. U.S. and Japanese teams met in advance of the surveys to outline a plan of action. At the end of the meeting, Blumenthal was not sure if there had been agreement to move forward with the joint operation. In a follow-up meeting, his counterparts from MEXT showed a hand-drawn map with several circles that represented how DOE and MEXT would work together. The Japanese process was not to make decisions in real time at formal meetings, but to take time to deliberate. Once determined, Blumenthal explained, the decision was put into action. The U.S. team learned to respect that process.

Challenges of Response Efforts to Disasters

Chuck Donnell, Vice President of Disaster Services Planning and Doctrine at The American Red Cross, noted that whether a disaster is predictable or considered a “black swan” event, it could have unimaginable consequences around the globe. He added that there are few incident management challenges more difficult for the U.S. government than facilitating an efficient, integrated, well-coordinated response to a CBRN event with an international partner; as one example, he cited the challenge that response efforts in other countries must ensure the safety of American citizens in the affected region.

Donnell identified three foundational principles for every disaster response regardless of hazard: preparedness, readiness, and nurturing the development of resilient communities capable of responding to myriad disasters. Preparation is the hallmark of effective response to large-scale disasters, he added; successful response is not accidental, organic or self-organized, whether domestic or international. Responding to major events and particularly a CBRN incident requires an inordinate amount of coordination in advance to build capabilities, including development, training, and testing of those capabilities within a known framework. In an international response effort, U.S. assistance should build upon existing local capabilities, commitments, and relationships, and efficient decision making should be facilitated at the lowest operational levels to be effective and timely. Donnell concluded by emphasizing the speed and availability of U.S. capabilities should be equal to the urgency of the need for the response.

U.S. Response to International Disasters

Colonel Patrick Terrell, WMD Military Advisor and Deputy Director for CBRN Defense Policy in the Office of the Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense for Combating WMD at the

Department of Defense, outlined four fundamental reasons the U.S. government responds to international disasters; 1) we stand by people in need—provide humanitarian assistance; 2) we take care of American citizens wherever they are; 3) we protect our forces overseas; and 4) we defend our homeland. In Japan, U.S. assistance was tied to some, if not all, of these principles, and the U.S government had a commitment to Japan as its ally. Terrell framed his comments using the Fukushima accident as an example, referring to important questions about effective U.S. response that were raised by this incident. How do we take care of American citizens in a foreign region? How do we evacuate people from a country when there is not an existing plan for noncombatant evacuation operations? How do we share information with vital allies and partners as quickly as possible? These are the types of questions being addressed by the U.S. government to improve our nation’s response capabilities in the future.

Terrell characterized areas where U.S. capabilities are very effective in international response and challenges that are faced once an event has happened. He emphasized that information is vital for an effective response, and posed that the United States is very good at collecting information but not as successful at sharing that information, whether within the U.S. government or with external partners. In the response to Fukushima, 17 federal departments and agencies were communicating multiple times a day within 24 hours. The challenge was ensuring that the right information was communicated to decision makers who needed to make strategic and tactical decisions quickly.

Relationships play a key role in effective international response, he added; it is important to have open lines of communication in place in advance of an event, both among federal agencies and between the U.S. government and their foreign counterparts. Terrell noted that because of his work with foreign consequence management policy, he and his counterpart at DOS had an established relationship built on trust and confidence. In Japan, where the U.S. government has military headquarters, U.S. military officers had established relationships with the Japanese Ministry of Defense and the Japanese Joint Staff. However, Terrell cautioned, relationships do not ensure that information will reach the appropriate parties. Following the earthquake and Fukushima accident, the United States received requests for assistance from multiple channels at multiple federal agencies; for example DOD received the same request for assistance as DOE. He emphasized that it is critical that the country team at the embassy provide the interface for all communication with a foreign government. Equally important, the U.S. government must be coordinated at home to avoid duplication of effort and to deliver resources and capabilities on the ground as quickly as possible. These factors are critical for saving lives.

Terrell cited current DOD activities focused on fostering better coordination and communication, which address questions such as how can DOD posture forces with key capabilities in effected regions quickly? How can DOD support countries so that they can respond on their own, particularly in the first few hours? How can DOD align army forces and combatant commands to promote building partner capacity and capabilities? Terrell stated that a current effort expands consequence management training to foreign civilian responders rather than solely military to military interactions. He noted that connecting with foreign civilians requires additional coordination between DOD and DOS, as they are the nexus of activity in the foreign nation.

Terrell concluded with two final points. The first underscored the need to consider how the U.S. government can foster interaction with international organizations and NGO’s in the face of a nuclear event since they are often the ones on the ground providing humanitarian assistance. And finally he noted that foreign partners may be overwhelmed by an event but not

realize it until it is too late, posing the question, how can the U.S. government help foreign governments understand an event clearly to promote more seamless coordination between all responding parties?

Private Sector and Non-governmental Organization Response to International Disasters

Brent Woodworth, President and CEO of the Los Angeles Emergency Preparedness Foundation, outlined issues that can arise in international response to disasters from the perspective of the private sector and NGO’s, and introduced some emerging technologies that can support the response to CBRN events. For over 30 years, Woodworth worked at IBM where he founded and managed a program called the Crisis Response Team (CRT), a group of experts who respond to disasters throughout the world. During his work with CRT, they responded to over 70 major events in 50 countries. Woodworth drew from specific cases to highlight lessons learned and challenges that occur when assisting in international response efforts.

In the aftermath of a large earthquake in Turkey, CRT faced the challenge that “people will ship anything” following a disaster. Woodworth described the situation in which the Turkish government was overwhelmed with the amount of medical supplies received from foreign donors. At the request of the minister of health, the CRT assisted with setting up seven warehouse operations and managed the receipt and distribution of medical goods and services. To complicate the process, not all incoming supplies were useable; for example, half used tubes of toothpaste and opened bottles of aspirin. Woodworth recalled that sorting and organizing these goods took an incredible amount of time, and added an additional layer to the logistical challenge of creating efficient systems for the Turkish government. Woodworth stressed that this is a common challenge following a disaster; large shipments of non-useable goods are sent to an affected country that will then have to be disposed, e.g., expired medicine or vast amounts of used clothes. To avoid this problem in the aftermath of the 2005 earthquake in the Kashmir region of Pakistan, Woodworth advised Prime Minister Aziz to ask the international community for a list of specific items needed for the response, such as winterized tents, blankets, and propane heaters. Pakistan received exactly what they needed based on that request.

Another important lesson learned is the need to match disaster assistance to the cultural and social structures of the country or region being assisted. Woodworth cited his work with the response to a large earthquake in Gujarat, India, which affected over 16 million people and caused complete devastation in some areas. During this response, the CRT faced local political and cultural sensitivities that needed to be addressed. Gujarat is a vegetarian state and food donations had to be carefully sorted. With the distribution of goods, response teams had to ensure that certain villages were not passed up based on political affiliations; this was accomplished by working with local government officials and other community leaders. Essential items that had been donated were held up because of customs fees; eventually fees were waived. Woodworth also highlighted how traumatic these events are to impacted families, and emphasized that meeting the needs of affected people requires specialized experts and programs that are customized to the unique cultural and social elements of the region.

Woodworth identified several additional challenges that can emerge in international disaster response. After a volcanic eruption near the capitol of Quito, the Ecuadorian government needed assistance with determining whether to evacuate the city or advise its citizens to shelter in place. During the response to the Indian Ocean Tsunami in Banda Aceh, the

massive devastation included a high number of fatalities, resulting in a large number of sanitation and health issues. Communication was critical, particularly because many affected people lived in remote, inaccessible areas. He also cautioned about working in areas of ongoing war and military action. Lastly, he stressed the importance of gathering and disseminating information, which is critical to making timely and appropriate decisions.

Woodworth cited operational questions, such as how do you find missing people? How can multiple organizations, agencies, governments, and others coordinate their efforts? Who is doing what? Are hospitals and other medical facilities capable of handling the influx of casualties? Woodworth offered that innovative technologies could address these questions and help foster coordination of response teams. He noted the open source software program Sahana,9 which was designed to provide information management solutions to assist disaster stakeholders better prepare for and respond to disasters. This software, which grew out of response activities in Sri Lanka following the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami, is widely used by emergency managers, NGO’s such as International Red Cross/Red Crescent (IFRC), local decision makers and government, among others. Following the Japanese earthquake and tsunami, Sahana was used to map the location of shelters, camps, hospitals, and other resources, as well as plot sources of contaminated water. The American Red Cross developed a standardized resource management system on Sahana to manage their volunteers, members, warehouses, and assets. Sahana also has tools to help locate and reunite families and manage shelters. Finally, Woodworth highlighted a new program, the Community Stakeholder Network, a network for business, government, nonprofit organizations, faith-based groups, and other community stakeholders where groups can share data and information with the goal of improving situational awareness before and after a disaster. The network can be customized for different sectors, so that different users can collect and display data in a way best suited to their needs. For example, maps of an area can be created with different overlays of information, such as population census, inventory, and infrastructure data.

Woodworth concluded by identifying several areas critical for international response. Most important, the U.S. government and other organizations must be invited by the host country. External governments and organizations must respect the government and be aware of and respectful toward cultural and societal issues and norms in the region. Honest communication with the public is a key component of response to a disaster. Woodworth underscored the need to define procedures, have a plan, and use sensible systems to implement the plan, break down silos, avoid redundancy of effort, and document everything. He closed by urging responding organizations not to be afraid to ask for help, saying that the most successful responders are the ones that admit they need assistance; ones that isolate themselves are doomed to failure.

Question and Answers

Lesperance, moderator of the session, opened with a simple question for each of the panelists, what are the top two priorities for response following an international CBRN event? Woodworth highlighted the importance of open and honest communication and building the trust of the country’s government and population. He added that it is critical to get information right

_______________

the first time. Following a large-scale disaster, Donnell observed, affected countries often cannot articulate their needs. To provide assistance and bring capabilities requires advance preparation and a line of communication with a responsible person in the center of the response. Often a country needs to be told what capabilities are available to assist them. Blumenthal said that from the technical side, it is important to respond quickly using well-practiced methods, and emphasized the need to be sensitive to cultural sensitivities and not surprise your partner. He added that decisions should be made based on the technical data that is available. Terrell drew on previous answers to sum up; a shared understanding of the situation on the ground is required as quickly as possible to employ the appropriate capabilities to address the incident. This happens with open, honest communication.

One participant asked if an independent government organization was needed to address standards, and roles and responsibilities of different responders, and to synchronize and coordinate response efforts. If so, should the effort have a domestic or international focus and work with the United Nations? On the international side, Woodworth responded, there is a need for coordination to address issues around resource allocation and to reduce redundancy of efforts. Donnell pointed out that successful mechanisms exist to coordinate the federal government with other response entities after a U.S. incident, and noted that the authority for making decisions following a domestic disaster lies with state and local governments. He re-emphasized the importance of preparation for international disaster deployments, indicating that responding to a situation becomes increasingly complex when requests are made through the country’s ambassador up to the President of the United States. Donnell also noted that NGO’s and private sector partners might already be on the ground when U.S. teams arrive. Donnell added that with CBRN events, there are only so many countries and organizations with the technical capability and capacity for response, e.g., following a nuclear accident. This helps to narrow the scope of coordination and planning that needs to occur in advance to build up robust capabilities.

A question was asked about how the United States can help other countries put systems and capabilities in place that are appropriate to their situation, rather than providing a one size fits all approach based on how the United States responds to a domestic CBRN incident. Terrell suggested that the country should state the problem directly and then work with the U.S. government to solve the problem specific to the situation, rather than the U.S. government presenting an “answer” to the problem. Woodworth added, “simpler is better”; don’t start with the newest, most innovative solutions that will not be sustainable over time. Blumenthal echoed Terrell and Woodworth, saying that in technical exchanges, he frames assistance in terms of the constraints of the issue rather than a right way to do things. Another participant pointed to an existing manual of emergency response standards, known as the Sphere Standards, used by the Red Cross, agencies, NGO’s, and United Nations (UN) responders, and asked if this system would be relevant for a CBRN event. Donnell stated that in his experience working through international disaster mechanisms, such as IFRC, the NGO community and UN cluster system, successful coordination is dependent on the individuals establishing the network at the time of the response. Woodworth suggested that the general relief capabilities outlined in the Sphere Standards could provide a useful model for a framework to address CBRN events. He added that the IFRC is adapting new systems to foster better coordination among NGO’s responding in foreign countries.

Another participant asked Blumenthal and Terrell if they could characterize the value of existing relationships in a moment of crisis and ways that emergency response capabilities could be built into existing relationships. Blumenthal explained that developing bilateral agreements at

the operational level is very helpful so that work can begin immediately following an incident. Additionally, continuing working relationships once they have been established is important; for example, he still works on data analysis with his counterparts in Japan. Setting the groundwork in advance is essential to having success, Terrell echoed. When a crisis comes, relationships will help to identify the issue and work out appropriate solutions. Moderator Lesperance directed a question to Terrell about how much capacity partner nations have with respect to a chemical event. Terrell responded that chemical events happen very quickly and that the focus may rapidly shift to caring for casualties from saving lives when a request is made for assistance. Building partner capacity to respond to a chemical event in advance is important so that the country can assess what has occurred and take action, for instance, to limit the spread of contamination and to know what types of assistance is required, for example, a request for additional respirators. Terrell added that it is vital to maintain relationships with NGO’s in other countries, as they may be the ones providing the bulk of the humanitarian assistance.

A question was posed to each panelist about whether there is an optimal blend of coordination and empowerment of responders who are operational on the ground. Can these capabilities be built into a system or are they based on the situation? Donnell used his experience in Haiti to frame his answer, indicating that there are multiple layers of coordination that have to be organized following large-scale disasters. Donnell observed that in the international community, organizations tend to gravitate toward a coordination mechanism based on the function they are performing, be it military, NGO’s, or the private sector. Oftentimes, the biggest challenge is to stitch those services into the leadership of the country in a way that the local government can organize and manage the operations. In Haiti, a fairly concise decision-making body was organized to assist the prime minister in addressing strategic issues. A second layer of coordination was set at the operational and tactical levels where the World Food Program was setting up different sites to distribute food. Donnell re-emphasized the importance of multiple layers of coordination and facilitating decision making at the lowest levels possible. What is often missing in responding to major disasters is the coordination mechanism for multiple stakeholders with multiple functions to come together and think holistically about the situation. From a technical response perspective Blumenthal identified three different situations that require different approaches, a) whether a large U.S. presence exists in a host country and the country provides a lot of support for the response, e.g., Japan; b) whether a large U.S. presence does not exist but the host country can provide support; or c) a situation where there is no U.S. presence and the host country is not equipped to respond. Woodworth emphasized that coordination between NGO’s and the private sector is critical, and that mapping and triage tools are used to help simplify decision making and improve situational awareness. Donnell pointed out that these issues are often the same in responding to international and domestic incidents.

References

Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA). 2013. The National Response Framework (2nd ed.). Available at http://www.fema.gov/national-response-framework.

National Diet of Japan Fukushima Nuclear Accident Independent Investigation Commission (Chairman: Kiyoshi Kurokawa). 2012. The Official Report of the Fukushima Nuclear Accident Independent Investigation Commission: Executive Summary Available at http://warp.da.ndl.go.jp/info:ndljp/pid/3856371/naiic.go.jp/en/report/.

White House and U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS). 2011. Presidential Policy Directive-8. Available at http://www.dhs.gov/xlibrary/assets/presidential-policy-directive-8-national-preparedness.pdf.