Current and Estimated Budgets for Air Traffic Control Staffing

As part of the congressional charge for this study, the committee was asked to consider “the Administration’s current and estimated budgets and the most cost-effective staffing model to best leverage available funding.” This chapter focuses on the “current and estimated budgets” elements of the charge. It describes the costs of the air traffic control (ATC) workforce in the context of the Federal Aviation Administration’s (FAA’s) total workforce and budget and establishes a baseline for “available funding.” Assessment of the cost-effectiveness of FAA’s models called for in the congressional charge is provided in the Summary.

The first three sections of this chapter examine the costs of current and future ATC budgets and the estimated revenue streams available to support them. Options for reducing the cost of ATC staffing and increasing revenues are discussed. These options are presented for illustration only and should not be interpreted as committee recommendations for alternative staffing strategies. The summary section places the cost of the ATC workforce in the context of the larger FAA budget issues facing the administration and Congress.

This section relies on the President’s FY 2014 and FY 2015 budget submissions for FAA. Estimated future budgets are taken from agency-level tables presented in an online appendix to the Analytical Perspectives appendix to the President’s FY 2014 and FY 2015 budget submissions.1

This chapter of the report was largely drafted during calendar year 2014, during which the President and Congress were engaged in a dispute over the federal budget and deficit. For the first 3 months of FY 2014, FAA operated under a continuing resolution that was based on the appropriated budget approved by Congress in FY 2012, as reduced by the Budget Control Act of 2011 (also referred to as sequestration).2 In January 2014, the President signed the Consolidated Appropriation Act of 2014, which implemented the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2013. That act, agreed to by the President and Congress in December 2013, brought an extended period of contentious debate about the federal budget to a temporary close. It established agency budget targets for FY 2014 and FY 2015 and set aside, for FY 2014 and 2015, significant cuts to discretionary portions of the federal budget that were otherwise required under the Budget

______________

1Fiscal Year 2014 Analytical Perspectives, Budget of the U.S. Government, http://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/default/files/omb/budget/fy2014/assets/spec.pdfz, accessed September 3, 2013. Detailed tables and out-year budget estimates for FAA were taken from Table 32-1, Federal Budget by Agency and Account, http://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/default/files/omb/budget/fy2014/assets/32_1.pdf (see page 268 of 449), accessed September 3, 2013.

2 The Budget Control Act (P.L. 112-25) requires automatic reductions to most federal discretionary budgets if Congress is unable to reach agreement on a deficit control strategy (Elias et al. 2013). Sequestration cuts to FAA’s FY 2013 budget totaled $636 million, of which $486 million came from FAA Operations. During FY 2013, Congress approved legislation allowing FAA to use unspent capital funds in the Airport Improvement Program to cover part of this cut.

Control Act of 2011. That act and its past and potential impact on FAA’s budget will be discussed in more detail later in this chapter.

The President’s FAA budget proposals for FY 2014 and FY 2015 provide the administration’s current view of budgetary needs; the appendices to the budget submission indicate the administration’s views with regard to budgets and aviation trust fund revenues in future years. The budget requests made in FY 2014 and FY 2015 are similar, with an important exception. During FY 2014, the administration revised its forecast of aviation trust fund revenues, which has important consequences for ATC staffing, as described later in this chapter. The funding ultimately appropriated by Congress for ATC for FY 2014 in the Consolidated Appropriation Act corresponds to the President’s request, and the amounts for FAA Operations as a whole are consistent. Tables in the chapter provide detail concerning requested and appropriated (enacted) amounts for FY 2014 and the President’s requests for FY 2015.

Staffing

FAA had a workforce of about 46,000 full-time equivalent (FTE) personnel in FY 2014.3 The ATC workforce accounts for about 14,900 of these FTEs, or about 31 percent of the total workforce (Table 6-1). Overall FAA and ATC staffing levels have been fairly consistent since at least 2012.

Budget

Operations accounts for 64 percent of FAA’s total budget (Table 6-2).4 It includes much more than simply the ATC workforce. As shown in Table 6-3, the Air Traffic Organization (ATO), of which ATC is a part, is the largest component of the Operations budget, accounting for three-quarters of the Operations total. Aviation Safety, the next-largest component, accounts for 12 percent of FAA’s budget, and Finance and Management accounts for 8 percent (Table 6-3).

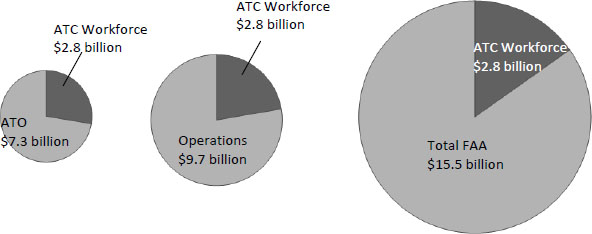

The total Operations budget was about $9.4 billion in FY 2013 and about $9.7 billion in FY 2014; ATO’s FY 2014 budget of $7.3 billion accounts for 76 percent of the latter amount (Table 6-3). According to figures provided by FAA, the cost of the ATC workforce covered in the controller workforce plans was $2.575 billion (for 15,100 controllers) in 2012, was $2.795 billion (for 15,000 controllers) in 2013, and was estimated to be $2.787 billion (for 14,900 controllers) in 2014. The $2.787 billion for the ATC workforce in 2014 represents about 38 percent of ATO’s FY 2014 budget, 29 percent of the Operations budget, and 18 percent of the total FY 2014 FAA budget (see Figure 6-1).

The ATC workforce is the main component of the ATO workforce and of the line item En Route and Oceanic and Terminal Services in ATO’s budget (Table 6-4). The total ATC workforce in FY 2014 is about 14,900, or about three-quarters of the FTEs shown in the En Route and Oceanic and Terminal Services row in Table 6-4. About 5,000 other personnel—supervisors, managers, and administrative personnel—who are not a part of the unionized work force are included in that row.

______________

3 Although requested staffing levels are available for FY 2015, this chapter refers to FY 2014 staffing levels to be consistent with data presented in previous chapters and with detailed information about the cost of the ATC workforce for 2012–2014 provided by FAA; these data are not available in the President’s budget submissions. Staffing levels are reasonably consistent between FY 2014 and 2015, as shown in Table 6-1.

4 Budget data presented throughout this report are in current dollars.

The next largest category of the ATO budget is accounted for by Technical Operations, which maintains ATC computers, radars, communications, and other equipment. Technical Operations represents about a quarter of ATO’s personnel and budget. These personnel are represented by a different bargaining unit and are not included in the ATC workforce considered in this report.

TABLE 6-1 FAA FTE Staff

| FY 2013, Actual | FY 2014, Enacted | FY 2015, Requested | Percent of Total FY 2015 Requested | |

| Operations | 41,055 | 40,471 (including 14,900 controllers) | 40,925 | 87.3 |

| Facilities and Equipment | 2,733 | 2,670 | 2,733 | 5.8 |

| Research, Engineering, Development | 248 | 249 | 249 | 0.5 |

| Grants-in-Aid for Airports | 555 | 605 | 608 | 1.3 |

| Other | 2,035 | 2,069 | 2,362 | 5.0 |

| Total | 46,626 | 46,064 | 46,877 | 100.0 |

SOURCE: President’s FY 2014 and FY 2015 budget submissions, FAA, Exhibit II-8.

TABLE 6-2 FAA Budget Authority by Function, FY 2013–2015

| FY 2013 Actual | FY 2014 Requested | FY 2014 Enacteda | FY 2015 Requested | Percent of Total FY 2015 Requested | |

| Operations | 9,148,465 | 9,707,000 | 9,651,422 | 9,750,000 | 63.8 |

| Facilities and Equipment | 2,613,627 | 2,777,798 | 2,600,000 | 2,603,700 | 17.0 |

| Research, Engineering, Development | 158,792 | 166,000 | 132,608 | 156,750 | 1.0 |

| Grants-in-Aid for Airports | 3,343,300 | 2,900,000 | 3,480,000 | 2,770,000 | 18.1 |

| Total | 15,264,184 | 15,550,798 | 15,864,030 | 15,280,450 | 100 |

NOTE: Amounts are in thousands of dollars.

a Does not reflect transfer of $253 million from Airport Improvement Program to Operations to fund air traffic controllers who otherwise would have been furloughed because of sequestration.

SOURCE: President’s FY 2014 and FY 2015 budget submissions, FAA, Exhibit II-1.

TABLE 6-3 FAA Operations Appropriation Line Items, FY 2013–2015

| FY 2013 Actual | FY 2014 Requested | FY 2014 Enacted | FY 2015 Requested | Percent of Total FY 2015 Requested | |

| ATO | 7,270,538 | 7,331,790 | 7,331,790 | 7,396,654 | 75.9 |

| Aviation Safety | 1,217,552 | 1,204,777 | 1,204,777 | 1,215,458 | 12.5 |

| Commercial Space Transport | 15,420 | 16,311 | 16,311 | 16,605 | 0.2 |

| Finance and Management | 551,669 | 807,646 | 762,462 | 765,047 | 7.8 |

| NextGen | 56,989 | 59,782 | 59,696 | 60,089 | 0.6 |

| Human Resource Management | 93,687 | 107,193 | 296,366a | 296,147a | 3.0 |

| Staff Offices | 189,810 | 199,801 | |||

| Total | 9,395,665 | 9,727,300 | 9,671,402 | 9,750,000 | 100 |

NOTE: Amounts are in thousands of dollars. NextGen = Next Generation Air Transportation System.

a The Human Resource Management and Staff Offices line items were combined in FY 2014 Enacted and FY 2015 Requested.

SOURCE: President’s FY 2014 and FY 2015 budget submissions, FAA, Exhibit III-1.

FIGURE 6-1 Cost of FAA workforce as a share of FY 2014 ATO, Operations, and total budgets.

TABLE 6-4 ATO Budget and FTE Staff

| FY 2013 Actual | FY 2014 Requested | FY 2014 Enacted | FY 2015 Requested | FY 2014 FTE | FTE % | |

| En Route and Oceanic and Terminal Services | 3,941,762 | 3,987,582 | 3,860,044 | 3,942,430 | 19,946 | 64.3 |

| Technical Operations | 1,664,199 | 1,716,181 | 1,586,695 | 1,587,678 | 7,923 | 25.5 |

| System Operations | 288,559 | 288,104 | 309,601 | 308,752 | 452 | 1.5 |

| Safety and Technical Training | 227,409 | 271,146 | 274,879 | 274,229 | 519 | 1.7 |

| Mission Support Services | 266,126 | 284,821 | 292,642 | 292,028 | 1,363 | 4.4 |

| Management Services | 276,632 | 170,355 | 326,341 | 327,287 | 239 | 0.8 |

| Program Management Organization | 605,851 | 655,675 | 661,589 | 664,250 | 575 | 1.9 |

| Program Adjustment | (62,074) | |||||

| Total | 7,270,538 | 7,311,790 | 7,311,791 | 7,396,654 | 31,017 | 100 |

NOTE: Amounts are in thousands of dollars.

SOURCE: President’s FY 2014 and FY 2015 budget submissions, FAA.

Since 1970, FAA has been funded mostly by the Airport and Airway Trust Fund (AATF). The fund is derived from a variety of taxes and fees imposed on aviation system users (see Table 6-5). Other funding is provided by the General Fund, which depends on tax receipts not dedicated to Social Security, Medicare, or other nondiscretionary programs and on federal borrowing. Shares of FAA funding covered by trust fund revenues and by the General Fund in the past and proposed for FY 2015 are shown in Table 6-6.

Most federal tax receipts to the General Fund come from individual federal income taxes; thus, loosely speaking, the general taxpaying public is the main source of federal income taxes that are dedicated to the General Fund.

The 7.5 percent ticket tax on commercial aviation users provides about 70 percent of the revenues into the AATF (Table 6-7). The tax rate has been unchanged since 1997 legislation (which phased in a reduction in the rate from 10 percent in 1996 to 7.5 percent by 1999). Other taxes that make up a modest share of total revenues (domestic flight segment tax, international arrival and departure tax, and a tax on flights between the continental United States and Alaska and Hawaii) have been pegged to the Consumer Price Index since January 1, 2002. The only new tax since 1997 is the surcharge on fractional ownership. It was introduced in March 2012 and accounts for 0.1 percent of total AATF revenues. As shown in Table 6-7, fuel taxes account for a small share of total revenues (about 5 percent), while ticket taxes and taxes on the use of international facilities account for 92 percent.

TABLE 6-5 Funding Sources and Tax Rates, AATF

| Aviation Tax | Comment | Tax Rate |

| Domestic passenger ticket tax | Ad valorem tax | 7.5% of ticket price |

| Domestic flight segment tax | Segment is one takeoff and one landing; segment fee does not apply to flights to or from rural airports | $3.80 per passenger in CY 2012 (indexed) |

| International arrival and departure tax | Head tax assessed on passengers arriving from or departing for foreign destinations (and U.S. territories that are not subject to the domestic passenger ticket tax) | $16.70 (indexed) |

| Flights between continental United States and Alaska or Hawaii | $8.40 international facilities tax plus applicable domestic tax rate (indexed) | |

| Frequent flyer tax | Ad valorem tax assessed on mileage awards (e.g., credit cards) | 7.5% of value of miles |

| Domestic cargo and mail | 6.25% of amount paid for the transportation of property by air | |

| General aviation fuel tax |

Aviation gasoline: $0.193 per gallon Jet fuel: $0.218 per gallon Fractional ownership surcharge: $0.141 per gallon (starting 3/21/2012) |

|

| Commercial fuel tax | $0.043 per gallon |

TABLE 6-6 Trust Fund and General Fund Budget Authority FAA Operations

| FY 2013 Actual | FY 2014 Requested | FY 2014 Enacted | FY 2015 Requested | |

| General Fund | 4,352,475 | 3,223,000 | 3,156,214 | 709,150 |

| AATF | 4,795,989 | 6,484,000 | 6,495,208 | 9,040,850 |

| Total | 9,148,464 | 9,707,000 | 9,651,422 | 9,750,000 |

NOTE: Dollar amounts are in thousands.

SOURCE: President’s FY 2014 and FY 2015 budget submissions, FAA, Exhibit II-4.

TABLE 6-7 AATF Revenues by Type of Tax

| AATF Tax | FY 2012 Revenues (millions of dollars) |

Share of Total (%) |

| Transportation of persons by air | 8,711.0 | 69.5 |

| Transportation of property | 492.0 | 3.9 |

| Use of international air facilities | 2,729.0 | 21.8 |

| Aviation fuel commercial use | 390.0 | 3.1 |

| Aviation fuel (other than gasoline) | 161.0 | 1.3 |

| Aviation gasoline | 39.0 | 0.3 |

| Any fuel used in fractional ownership flight | 11.0 | 0.1 |

SOURCE: http://www.faa.gov/about/office_org/headquarters_offices/apl/aatf/.

Aviation taxes and fees are imposed on National Airspace System users, but not in proportion to their use of the system (Table 6-8). Commercial aviation accounts for 62 percent of ATC operations but pays 98.3 percent of AATF user fees. General aviation accounts for 38 percent of ATC operations but pays only 1.7 percent of AATF user fees.5

For many years, Congress and various administrations have debated the extent to which user fees (revenues of the AATF) should cover aviation system costs (Elias 2010, 13). In the 110th Congress, the Bush administration proposed an increase in user fees and a requirement that the AATF cover most aviation system expenses (Elias 2010). These proposals were not adopted by Congress. The 111th Congress debated various proposals to raise user fees and taxes, including those on general aviation, but the result was a stalemate. The FAA Modernization and Reform Act of 2012 ultimately left tax rates unchanged, with the exception of the increased tax on fuel for fractionally owned aircraft mentioned previously.

In its FY 2014 budget submission, the Obama administration proposed raising a variety of taxes and fees related to aviation, several of which are not revenue sources dedicated to the AATF.6 (One of the administration’s proposals, to increase fees for airline security from $2.50 to $5.00, was adopted in the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2013.) With regard to AATF revenues, the administration also proposed a new fee of $100 per flight, which it repeated in its FY 2015 budget submission. The fee would apply to all aircraft that fly in controlled airspace except for piston aircraft, military and government flights, air ambulances, and Canadian aircraft overflights. The administration’s premise is that aviation users who consume ATC services should pay for them, as opposed to taxpayers paying through the General Fund. Both commercial and general aviation interest groups strongly oppose the administration’s aviation tax increase proposals, including the per flight fee, which Congress has rejected in previous years.

TABLE 6-8 Share of Taxes Paid and Share of ATC Operations by User Type, 2012

| Share of Taxes Paid to Trust Fund (%) | Share of ATC Operations (%) | Share of Tower Operations (%) | Share of TRACON Operations (%) | Share of ARTCC Operations (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| General aviation (Part 91) | 1.7 | 38 | 54 | 38 | 17 |

| Commercial aviation (Part 121 and 135) | 98.3 | 62 | 46 | 62 | 83 |

NOTE: TRACON = terminal radar approach control; ARTCC = air route traffic control center.

______________

5 For the purposes of this analysis, the committee defined general aviation as comprising both piston-engine aircraft powered by aviation gasoline and turbine-engine aircraft powered by kerosene when operated under Part 91.

6 Included would be an increase in the security fee (from $2.50 to $5 per one-way segment), international custom duties (from $5.50 to $7.50), immigration services fees (from $7 to $9), and an allowance for large airports to raise passenger facility charges to $8 while reducing large airport eligibility for Airport Improvement Program funds. Security, customs, and immigration fee increases would help defray the costs of security screening of passengers and cargo at airports, customs inspections, and immigration services that are covered by general revenues paid by taxpayers. Passenger facility charges would allow large airports to increase fees to pay for airport facilities and services.

The administration proposal leaves the 7.5 percent ticket tax unchanged. Over the past 10 years, however, airlines have limited increases in the cost of tickets by introducing ancillary fees for a growing range of services, including checked baggage, meals, blankets and pillows, early boarding, seat selection, and in-flight entertainment. The Internal Revenue Service has determined that many of these ancillary fees are exempt from the 7.5 percent excise tax that provides revenue to the AATF. Hence, “airlines increasing reliance on fees reduces the proportion of their total revenue that is taxed to fund FAA” (GAO 2010, 1). For example, if ancillary fees for checked baggage had been subject to taxation, the associated AATF revenue would have been approximately $248 million in 2013.7 The revenue losses associated with tax-exempt fees led the Government Accountability Office to raise the possibility that Congress “may wish to consider amending the Internal Revenue Code to make mandatory the taxation of certain or all airline imposed fees and to require that the revenue be deposited in the Airport and Airway Trust Fund” (GAO 2010, 35).

Opinions have varied over time about the share of FAA Operations that should be covered by the trust fund (Fischer 2008). When the AATF was established in 1970, spending on operations was allowed, but the following year the Airport and Airway Development and Revenue Acts Amendments of 1971 (P.L. 92-174) effectively banned such operations spending. Shortly thereafter, in 1976, Congress amended the legislation to allow for partial coverage of FAA operating expenses by aviation trust fund revenues. For 1 year, FY 2000, the AATF covered the full expenses of FAA, both capital and operating, but otherwise, some operating expenses have been covered by the General Fund.8 With the enactment of the Aviation Investment and Reform Act for the 21st Century (AIR21) in 2000, Congress made clear that capital expenditures—Facilities and Equipment and the Airport Improvement Program (AIP)—had first call on trust fund revenues (GAO 2012a, Footnote 18). Any residual AATF revenues would be available to cover a share of the cost of Operations.9 Since enactment of AIR21, from 2001 through 2010, the General Fund covered between 8 and 33 percent of FAA’s total appropriation (between 16 and 57 percent of FAA Operations expenses) (GAO 2012a, 6).

As Fischer (2008) points out, most observers have concluded that a share of FAA’s operating expenses should be paid by the General Fund to cover activities such as ATC services provided to the military.10 General aviation and corporate jet operators have contended that ATC provides a safety function that is a public good and should therefore be paid for by the general public. In this report, the committee makes no judgment as to the appropriate share of FAA’s expenses to be covered by the General Fund or how much various user groups should pay.

The ATC workforce is not the only component of the FAA Operations budget that is partly supported by General Fund revenues. ATO received about $3.55 billion in General Fund support in 2013, or about 80 percent of the $4.4 billion in General Funds appropriated for FAA

______________

7 The U.S. Department of Transportation’s Bureau of Transportation Statistics (2014) reports that U.S. passenger airlines took in $3.3 billion in baggage fees in 2013, resulting in an estimated revenue loss of about $248 million ($3.3 billion × 7.5 percent = $247.5 million). An increase in taxes would reduce demand slightly, but the effect would likely be small because of the small increase in the ticket price ($50 × 7.5 percent = $3.75).

8 Congress deliberately covered Operations out of the AATF in 2000 to draw down the balance in the fund, which had built up over previous years.

9 AIR21 and subsequent legislation also required that AATF revenues be appropriated so that user taxes credited to the AATF would not build up substantial unobligated balances in the trust fund, as had happened during some years in the past.

10 Fischer (2008, 12–13) provides a good overview of the economic arguments about whether ATC is a “public good” and therefore should be funded by all taxpayers rather than only by aviation users.

Operations.11 About $1.3 billion in General Fund revenues was used for ATC staffing in FY 2013, or about 37 percent of ATO’s total General Fund support and 29 percent of the total General Fund revenues for FAA Operations. These shares remain the same for FY 2014, but the total amount of General Funds appropriated, $3.2 billion, is considerably below the amount required in FY 2013, and the administration requests significantly less in FY 2015. The increase in trust fund support for FAA Operations in FY 2014 was made possible by growing revenues to the fund. Although total operations and total commercial flights have declined over time, as discussed in previous chapters, commercial flights have been holding steady and are operating with much higher load factors. Thus, more passengers are paying the ticket tax than in recent years, and the ticket tax is the main source of AATF revenues.

Both the administration (through the Department of the Treasury) and Congress [through the Congressional Budget Office (CBO)] forecast AATF income (receipts from taxes and interest). The forecasts are based on macroeconomic trends as opposed to aviation activity. The forecasts initially made in FY 2014 differ substantially. By 2018, for example, the administration initially forecast AATF receipts (and interest) to total $15.8 billion, compared with CBO’s forecast of $18.7 billion. In late 2013, Treasury staff indicated that they had adjusted their forecast of AATF receipts. In the President’s FY 2015 budget submission, the Treasury forecasts AATF receipts for FY 2018 of $17 billion, which is $1.2 billion more than forecast in the FY 2014 submission. The administration’s revised forecasts, if realized, would result in a reversal of the growing dependence of FAA Operations on the General Fund and substantially ease the budgetary pressure caused by the ATC workforce.

Over time, a rebound from the slow-growth economy since the recession of 2008–2009 will improve AATF revenues as more tickets are purchased for an increasing number of flights and carriers purchase more fuel and equipment (as noted, 70 percent of AATF revenues comes from ticket taxes). Demand for aviation services tracks closely with overall measures of economic activity. The administration’s FY 2014 forecast for the AATF to 2018 assumes an average annual growth rate of about 5 percent, consistent with its forecast for growth in gross domestic product. Its revised FY 2015 forecast assumes an average annual growth rate of 6.7 percent. AATF revenues are forecast to rebound from $11 billion in 2013 to $18.7 billion by 2018 according to CBO’s May 2013 estimates.12 Such an increase would require an average annual growth rate of 7.5 percent, well in excess of the administration’s FY 2014 forecasts. The difference matters considerably, because CBO’s forecasts indicate that the AATF would have sufficient revenues to cover FAA’s capital and all its operating expenses as early as FY 2017. The administration’s revised forecast for FY 2015 is reflected in its FY 2015 budget request for General Fund revenues for Operations, which, at $709 million, is $2.4 billion less than required in FY 2014 (see Table 6-6). Whether the administration’s revised forecasts (which are based on the 6.7 percent growth rate mentioned above) will hold is open to question. FAA’s 2013 forecast

_____________

11 FAA—President’s 2014 budget submission, page 52 of 826. According to FAA, the share of General Funds for Operations (about 47 percent in 2013) is applied equally to all the subcomponents of the FAA Operations budget, including ATC.

12 CBO Reestimate of President’s 2014 Budget Request. Airport and Airway Trust Fund (AATF) Projection of Trust Fund Balances, May 2013. Table provided by CBO.

of revenue passenger miles, an indicator of future ticket tax revenue, has an average annual growth rate of only 3 percent. Trust fund revenues have grown substantially in recent years, even though total flights have held steady, because of increasing load factors. With most flights operating close to maximum capacity, however, opportunities for further load factor growth are limited. Hence, future revenue growth will depend on the strategies adopted by the airline industry to meet growing demand.

The administration’s original FY 2014 forecasts (prerevision) are more conservative than those of CBO and are more consistent with FAA’s assumptions about future aviation activity. In its 2013 forecast of aerospace activities, FAA estimates that U.S. commercial carrier revenue passenger miles (both domestic and international) will grow by an average annual rate of 3.2 percent through 2018 (FAA n.d., Table 6). However, FAA’s forecast of ATC workload—total operations—grows by only 1.3 percent through 2018, which is consistent with the trend toward higher load factors and the use of larger aircraft.13 Forecasts of air traffic growth from airplane manufacturers are more modest than the forecasts from the administration and CBO. Both Airbus and Boeing anticipate world traffic growth of about 5 percent annually but expect lower growth rates in the advanced economies of Europe and North America. For North America, Airbus forecasts a 3.0 percent growth rate and Boeing a 2.7 percent growth rate (Airbus 2013; Boeing 2013).

As part of FY 2015 Analytical Perspectives (Table 29-1), the administration forecasts budget authority and outlays for FAA, but only at the level of major budget category. Hence, it is only possible to review estimates at the level of future FAA Operations budget authority (authority to obligate current and future year expenditures) rather than the budget for ATC staffing. The administration reports FAA Operations budget authority of about $9.6 billion in 2013, which is estimated to grow to $10.6 billion by 2018. The average annual growth rate of 2 percent is fairly consistent with an estimated 1.3 percent average annual growth rate in workload (on the assumption that some of the higher rate for budget authority is accounted for by inflation).

As noted, between 2003 and 2012 FAA’s Operations budget received between $2 billion and $4 billion annually from the General Fund (GAO 2012a, Figures 7, 8). As shown in Table 6-6, this figure reached $4.4 billion in 2013 but dropped to $3.2 billion in FY 2014. The President’s FY 2015 budget submission indicates that the General Fund contribution would drop to $709 million in FY 2015, nearly $4 billion less than required as recently as FY 2013. In the final appropriation for FY 2014, Congress appropriated $3.2 billion in General Funds (Table 6-6), which it achieved through a combination of a substantially increased allocation from the AATF compared with 2013 and a slightly reduced budget for FAA Operations, as explained in the following text. Congress cut FAA’s Operations FY 2014 budget by $56 million compared with the amount requested (Table 6-3), while it funded ATO at the level requested. [Cuts in the Operations budget were made to requested funds for administrative expenses (Table 6-3).] Congress also cut Grants-in-Aid for Airports, but not as much as the administration requested; the amount appropriated for the AIP for FY 2014 is $3.48 billion (about the same as provided for

______________

13 Between 2013 and 2022, estimated annual average rates of change are as follows: for air carrier operations, growth of 2.6 percent; for air taxis and commuters, a decline of 0.6 percent; for general aviation, growth of 0.4 percent; and for military, growth of 0.8 percent.

FY 2013 and $580 million more than the administration requested for FY 2014). Instead of allocating $3.3 billion from the General Fund, Congress appropriated $3.2 billion, while increasing the contribution from the AATF from $4.8 billion in FY 2013 to $6.5 billion in 2014, as the President requested (Table 6-6).

The Appendix to the 2015 Analytical Perspectives indicates that the administration expects the General Fund to cover only $709 million of FAA Operations budget authority in FY 2015, and the administration expects the General Fund’s contribution to stay below $800 million until 2021.14 If these forecasts hold, the demand for General Fund revenues to cover FAA Operations expenses may not be as significant a budget issue as it has been in the past.

The administration’s FY 2014 and 2015 budget submissions would manage the future growth in Operations expenses, in part, by reducing the AIP from $3.35 billion in FY 2013 to $2.9 billion in FY 2014 and holding the AIP constant at that level in coming years.15 During 2013, Congress did allow FAA to divert funding from AIP to avoid furloughs of ATC staff and closure of many low-activity contract towers, as would have been required under sequestration. However, the AIP is popular in Congress and has strong advocates, so whether Congress will agree with that strategy in the long term is unknown. Of course, Congress could make other choices within its capital budget. For example, it could stretch out the period for implementation of the Next Generation Air Transportation System (NextGen) to make more aviation trust revenues available for FAA Operations.16

Late in 2013, Congress enacted the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2013, which guides appropriations for FY 2014 and 2015. Under this legislation, non-Defense domestic programs are funded at $468 billion for FY 2014, which is $24 billion more than allowed under the 2013 continuing resolution. The Bipartisan Budget Act of 2013 provides relief for 1.5 years from the automatic, across-the-board budget cuts required by the Budget Control Act of 2011 (P.L. 112-25). This legislation requires automatic reductions to most federal discretionary budgets until Congress reaches agreement on a deficit control strategy as required under the law (Elias et al. 2013). Sequestration cuts to FAA’s FY 2013 budget totaled $636 million, of which $486 million came from Operations. Potential budget cuts from sequestration complicate any forecast of agency budgets beyond FY 2015. If Congress is unable to agree on a long-term plan to reduce the deficit and thereby allows sequestration to continue in that year, the cuts to ATC staffing would be unprecedented in scope and impact relative to the demand for aviation. Five years of sequestration cuts of approximately 5 percent annually, for example, applied proportionately on FAA’s budget, would reduce the FY 2014 ATC budget of $2.787 billion by nearly $700 million, or 25 percent. Such a cut would require a commensurate reduction in staffing of approximately 3,725 controllers.

The roughly $2.8 billion cost of the ATC workforce for FY 2014 could be reduced if the size of the workforce was reduced, but the budgetary savings would be modest for plausible

______________

14 Until FY 2011, forecasts of AATF receipts were made by FAA, but they are now made by the Department of the Treasury. Between 2001 and 2010, FAA forecast AATF receipts that were more than $9 billion in excess of actual receipts (GAO 2012a, Figure 4).

15 See Table 32-1 in Appendix to Analytical Perspectives, page 270. At the time of this writing there was an obligation limit on AIP of $2.9 billion for FY 2014, but it would increase to $3.55 billion by 2023. The administration proposes to hold AIP at $2.9 billion through 2023, so Congress would have to agree to cut future AIP appropriations below the obligation limit. The administration pairs its cut to AIP with a proposal to allow large airports to increase passenger facility charges dedicated to airport improvements.

16 The Government Accountability Office has been critical of FAA’s estimation of the cost and schedule for the NextGen program and its ability to meet proposed schedules for NextGen implementation (GAO 2012b).

reductions in the number of controllers, while the impact on system performance could be significant. The following “thought experiment” is provided to make this point. As mentioned in Chapter 3, FAA staffs for the 90th percentile busiest day, but it could staff for the median day (the 50th percentile day) instead. Use of the 50th percentile for planning purposes means that half of the time there would not be sufficient personnel to respond to demand, which would result in flight delays or cancellations during peak periods. The safety effects are uncertain, since FAA would limit the number of flights to what ATC could manage. The point of this discussion is not to propose staffing at the 50th percentile, but merely to observe that the savings from staffing at that level would be modest. Use of the 50th instead of the 90th percentile busiest day in the staffing calculations would reduce the number of ATC staff needed by only about 8 percent. The budgetary savings from an 8 percent cut in ATC staff would be in the range of $223 million (8 percent of $2.787 billion), which represents about 1.4 percent of FAA’s annual budget and only 7 percent of the General Fund revenues proposed for FAA Operations in 2014.

The policy conundrum for FAA and Congress has been that the agency has required a growing level of support from the General Fund to cover the cost of its operations. If the administration’s revised forecasts of AATF revenues hold, this trend would be reversed, but whether the forecasts will hold is unknown.

The ATC workforce received approximately $1.3 billion of the $4.4 billion in General Fund revenues allocated to FAA in FY 2013, a sizable proportion. General Fund revenues are in demand across the entire discretionary budget. In this context, FAA and Congress have limited choices: cutting services (and costs), raising revenues, or increasing deficit spending.

A politically less difficult choice would be to cut costs without reducing services commensurately. For example, FAA and Congress could adjust to a lower level of funding from the General Fund by making many other changes in the overall FAA budget—such as stretching out the NextGen program or agreeing to administration proposals to cut funding allocated to the AIP—rather than by cutting ATC staffing levels. Congress has done so as recently as 2013 to avoid FAA’s planned furloughs of ATC staff and the closing of low-activity contract towers in response to the first round of cuts under sequestration. In addition, FAA will be able to reduce the cost of ATC staff in coming years as a consequence of the pending retirement of the large number of controllers hired to replace those fired in the 1981 Professional Air Traffic Controllers Organization strike (a lower proportion of the remaining employees will have the most seniority). In anticipation of these retirements, FAA has hired many trainees so that they will be fully trained before the retirements occur. Other options would be to cut overhead expenses by reducing the number of ATC managers and supervisors17 and to cut costs by increasing the number of contract towers and consolidating services into fewer facilities. Options for enhancing the revenues needed to support ATC services could also be considered.

______________

17 The FAA Modernization and Reform Act of 2012, Title VI, Section 604, calls for an independent study of frontline manager staffing. It had not been released at the time of this writing.

Contract Towers

As noted in Chapter 1, ATC services at some low-activity towers are provided by private-sector organizations under contract to FAA. The agency has operated its Federal Contract Towers program for more than 30 years, and as of 2014, there were 252 towers in the program. The Office of Inspector General of the U.S. Department of Transportation (OIG) estimates that contract towers cost about $1.5 million less on average than low-activity towers managed by FAA (OIG 2012a). The OIG attributes this to (a) contract towers having fewer total personnel (10 fewer ATC personnel on average than comparable FAA-operated towers) and (b) contract tower controllers being paid significantly less than FAA controllers.18 In addition, contract towers operate at times with a single controller, whereas FAA requires its towers to operate with a minimum of two controllers in most circumstances.

As indicated in Chapter 2, the committee has reservations about the OIG’s conclusion that contract towers offer a level of safety comparable with that of FAA-operated towers (OIG 2012a). The committee’s reservations center on the difficulty of establishing analogous groups of FAA towers and contract towers for comparison purposes and on differences in safety reporting practices at the two types of tower. The assumption, for purposes of illustration, that the safety levels of FAA-operated and contract towers are equal implies that FAA could contract out more low-activity towers to reduce its costs without reducing safety. As noted in Chapter 2, most of the reduction in operations since the peak in 2000 has occurred in general aviation rather than in commercial operations, which suggests that demand on low-activity towers has decreased. The OIG found that of the 315 FAA-operated facilities, about 90 towers had traffic density levels similar to those of contract towers. This implies that, given the average $1.5 million lower annual operating cost of contract towers, FAA could save about $135 million annually by contracting out operation of these towers (90 comparable FAA-operated towers multiplied by the $1.5 million average lower operating cost at contract towers). Doing so would require a reduction in FAA’s controller workforce of about 900 (90 facilities times 10 more ATC personnel in comparable FAA-operated towers than in contract towers). Such a strategy would likely arouse strong opposition from the National Air Traffic Controllers Association, as in 1998, when an attempt was made to privatize 22 towers. The strategy would reduce the number of controllers by 6 percent and the cost of the ATC workforce by 5 percent. The savings would be less than 1 percent of FAA’s budget. Whether such savings could be achieved without compromising safety is questionable. Much more modest, but less controversial, savings could be achieved by curtailing 24-hour staffing at FAA towers with low activity (OIG 2013).19

Another cost-saving option for FAA could be to close the lowest-activity towers, including contract towers, although experience suggests that this option would face strong opposition from Congress. In anticipation of the sequester budget cuts, FAA announced its intention to close up to 238 low-activity towers, including 195 contract towers. The agency subsequently announced that it would close 149 contract towers for a 4-week period beginning in April 2013 but later deferred the proposed closures by 2 months to address objections from a

______________

18 Many contract tower employees are former FAA or military controllers who may be drawing a pension and have less need for a salary comparable with that of controllers in FAA-operated towers. Both groups are represented by the National Air Traffic Controllers Association.

19 The OIG (2013, 20) has recommended that FAA “identify the terminal air traffic facilities that do not meet the established minimum criteria for midnight shift operations, and (a) evaluate the safety risks and benefits of reducing their hours of operation, and (b) develop milestones for implementation of the reduction of operating hours at the selected facilities and report the status and justification for each selected facility to the OIG in 180 days.”

range of stakeholders (Elias 2013). The situation was resolved at the beginning of May 2013 by the passage of the Reducing Flight Delays Act (P.L. 113-9), which allowed FAA to transfer money from the AIP to keep open the 149 contract towers slated for closure. A letter to the Secretary of Transportation and the FAA Administrator from a bipartisan group of 25 senators clarified the objective of the legislation, noting that “[c]ongressional intent is clear: the FAA should prevent the slated closure of 149 contract towers by fully funding the contract tower program” (as cited by Elias 2013, 2). In light of this statement, any suggestion that local funding be increased to keep low-activity towers open also appears unlikely to receive congressional support, particularly since Congress has limited the local share under the Federal Contract Tower program to not more than 20 percent of a tower’s costs (Elias 2013).

Facility Consolidation

FAA must consider consolidation of facilities for a variety of reasons: some of its outdated buildings housing ATC services must be replaced or significantly upgraded (OIG 2012b), installation of NextGen technologies will require new facilities when older ones cannot accommodate the new physical demands, and overall budget pressures force the agency to reduce operating costs. FAA is directly responsible for 425 facilities hosting ATC en route and terminal services. Most are in fair to good condition, but some require replacement (GAO 2013; OIG 2012b).20

As required by the FAA Modernization and Reform Act of 2012 (Title VIII, Section 804), FAA is developing a long-term facilities consolidation report to simplify the transition to NextGen and to “reduce capital, operating, maintenance, and administrative costs of the FAA where such cost reductions can be implemented without adversely affecting safety.” Consolidation of facilities could, in principle, reduce the demand for the number of controllers. With a larger number of staff at the same facilities, managers would have more options for filling duty rosters in response to planned and unplanned leave. For this option to work, a sufficient number of controllers would need to be trained and certified to cover multiple positions. In some past consolidations, such as the Potomac Terminal Radar Approach Control facility, FAA combined staff from multiple facilities, but controllers did not certify on positions in sectors other than those they formerly controlled. Hence, the larger workforce did not provide additional flexibility to managers in making assignments (OIG 2012b). In addition, when consolidations have merged controllers trained to handle complex, high-volume air traffic with those accustomed to handling light traffic in nearby facilities, many controllers in the latter category have not been able to certify on the positions requiring control of more complex traffic. However, past consolidations have allowed for reductions in administrative staffing.

Although FAA has a long history of consolidating facilities as technology has advanced and opportunities have arisen, recent large-scale consolidations have not achieved anticipated efficiencies because of such factors as renegotiated wage rates, relocation expenses, transfers of controllers unable to certify, construction cost overruns, and other technical challenges (OIG 2012b, Table 6).

Most consolidations have been planned with the intent of improving capacity and efficiencies in airspace management. Other benefits cited have been cost reductions in administrative staffing and maintenance of facilities. However, it is much easier and safer to

______________

20 FAA operates in more than 1,200 facilities—centers, towers (including contract towers), administrative offices, and training and research offices. Most are leased.

begin operation in a new facility with known airspace and procedures that were in place in the facilities being consolidated. Once staff have been assimilated into a new facility and have become familiar with new equipment and working arrangements, managers can assemble groups of users and workers to begin developing the more efficient airspace and procedures that were envisioned. Airspace redesigns are necessarily done in phases. Each phase is developed, reviewed, and simulated in conjunction with labor unions and users, and when that process is completed, the workforce is trained. Both airspace users and organized labor must participate in the development of any redesign and agree on the changes to be made. The final approved changes often differ from those proposed since they take account of local conditions. Planned improvements in airspace design and any associated staffing efficiencies envisioned as part of a facility consolidation will not materialize until managers, controllers, and users can work out the details in the new facility. Thus, it is not surprising that the outcomes of consolidations have not always matched expectations.

In the future, technology may allow for the provision of some air traffic services at low-activity airports from remote locations through the use of surface surveillance systems to control aircraft rather than through visual means (the controller looking out of the window). Thus, the operations at a number of low-activity stand-alone towers could be consolidated at a single remote facility. This option may offer operational cost savings, although start-up costs could be high and the level of service provided to pilots operating under visual flight rules might be reduced. FAA is investigating technologies for such staffed NextGen towers, and similar initiatives are under way in Scandinavia and Australia. However, remote ATC tower facilities are unlikely to be “ready for routine operation at U.S. airports in the near future” (Elias 2013, 8).

In the long term, the implementation of NextGen may afford FAA the opportunity to undertake more extensive consolidations and to move facilities out of some high-cost-of-living areas that are difficult to staff. Air route traffic control center and terminal radar approach control facilities, for example, could be geographically separated from the areas they serve. However, the feasibility of such consolidations and relocations would depend on the availability of funding, the anticipated benefits versus the likely cost, and political considerations. As noted elsewhere in this report, FAA has reported that no direct impacts on the overall workforce resulting from NextGen have yet been identified. Hence, FAA appears not to be planning for significant cost savings in ATC staff as a result of consolidation or relocation of facilities for NextGen.

An additional factor may be congressional concerns with regard to gains and losses of controller jobs among members’ districts. Losses of controller jobs have been particularly controversial and have made some consolidations difficult to enact.

Enhanced Revenues

The mainstay of the AATF—the 7.5 percent ticket tax—has not been increased since 1999. Since that time, the revenues produced by the tax have declined because the tax base has been eroded by airline practices of unbundling and charging fees for ancillary services. In view of the challenges facing the commercial aviation industry, Congress may continue to be reluctant to increase taxes that dampen demand, although the increase in security fees approved as one part of the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2013 indicates that modest increases in user fees are possible. Other administration proposals—to raise aviation-related taxes and fees for customs and immigration services and to impose a $100 per flight fee that would more fairly charge business

and private jet users for ATC services provided—have not been enacted. As noted above, commercial aviation bears almost the complete burden of paying AATF taxes but receives less than two-thirds of ATC services. General aviation, in contrast, consumes more than one-third of ATC services and pays only 1.7 percent of AATF taxes.

One of the policy questions that gave rise to this study—the affordability of the ATC workforce at its current level of $2.78 billion for FY 2014—cannot be answered in isolation from the broader trends in demand for ATC services and interrelated policy issues. The cost pressures on staffing for ATC services may persist. The budget environment is complicated and constrained. Across-the-board cuts in discretionary budgets required by the Budget Control Act of 2011 have been postponed until FY 2016, but if Congress remains unable to reach a long-term plan to reduce the federal deficit, sequestration cuts to ATC services, compounded annually, would be extraordinary in their impact on aviation. Demand for air transportation will grow as the economy recovers, but by how much is unclear. At current fee levels and tax rates, the growth in AATF revenues as traffic rebounds may not be sufficient to cover the growth in FAA’s operating costs. The assumptions underlying the administration’s FY 2015 budget forecasts with regard to growth in AATF revenues are more optimistic than FAA’s forecast growth in commercial aviation activity.

Illustrative options for managing cost pressures related to the ATC workforce in the event of lower-than-forecast AATF revenues were described, but they would require substantial effort by FAA. Consolidation of facilities, in principle, could reduce the number of controllers needed, but recent consolidations have not been successful in this regard. In addition, FAA does not appear to be planning on economies in controller labor costs as part of the facility consolidations for NextGen. As indicated above, an 8 percent reduction in staffing (about 1,200 controllers) could be achieved by staffing for the 50th rather than the 90th percentile day, which would imply annual savings in the range of $223 million, or 1.4 percent of FAA’s budget. However, such a reduction would impose economic costs associated with delay and canceled flights and would have unknown effects on aviation safety. Contracting out more low-activity towers would be consistent with the considerable decline in general aviation operations since 2000; FAA might be able to reduce its workforce by as many as 900 and save $135 million annually (less than 1 percent of its budget). However, the impact on safety would be unknown, and strong opposition from organized labor would be certain.

Congress could also consider ways to increase fees charged to the consumers of air traffic services. Airline practices with regard to charging ancillary fees for baggage handling, a service formerly included in overall ticket costs and subject to the ticket tax, effectively cause the AATF to lose on the order of $248 million annually in tax revenue. Furthermore, general aviation is a large consumer of ATC services requiring considerable ATC staffing at lightly used airports. The cost of these controllers is paid for by taxpayers and passengers using commercial aviation rather than by general aviation users.

REFERENCES

Abbreviations

| FAA | Federal Aviation Administration |

| GAO | Government Accountability Office |

| OIG | Office of Inspector General, U.S. Department of Transportation |

Airbus. 2013. Global Market Forecast: Future Journeys, 2013–2032. http://www.airbus.com/company/market/forecast/?eID=dam_frontend_push&docID=33755.

Boeing. 2013. Current Market Outlook, 2013–2032. http://www.boeing.com/assets/pdf/commercial/cmo/pdf/Boeing_Current_Market_Outlook_2013.pdf.

Bureau of Transportation Statistics. 2014. 4th-Quarter and Annual 2013 Annual Financial Data. Press Release BTS 22-14, May 5.

Elias, B. 2010. Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) Reauthorization: An Overview of Legislation in the 111th Congress. R40410. Congressional Research Service, March 30.

Elias, B. 2013. Proposed Cuts to Air Traffic Control Towers Under Budget Sequestration: Background and Considerations for Congress. R43021. Congressional Research Service, May 7.

Elias, B., C. T. Brass, and R. S. Kirk. 2013. Sequestration at the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA): Air Traffic Controller Furloughs and Congressional Response. R43065. Congressional Research Service, May 7.

FAA. n.d. FAA Aerospace Forecast, Fiscal Years 2013–2033. http://www.faa.gov/about/office_org/headquarters_offices/apl/aviation_forecasts/aerospace_forecasts/2013-2033/media/2013_Forecast.pdf.

Fischer, J. 2008. Aviation Finance: Federal Aviation Administration Reauthorization and Related Issues. RL33913. Congressional Research Service.

GAO. 2010. Commercial Aviation: Consumers Could Benefit from Better Information About Airline-Imposed Fees and Refundability of Government-Imposed Taxes and Fees. GAO 10-785. July.

GAO. 2012a. Airport and Airway Trust Fund: Factors Affecting Forecast Accuracy and Realizing Future FAA Expenditures. GAO 12-222. Jan.

GAO. 2012b. Air Traffic Control Modernization: Management Challenges Associated with Program Costs and Schedules Could Hinder NextGen Implementation. GAO 12-223. Feb.

GAO. 2013. FAA Facilities: Improved Condition Assessment Methods Could Better Inform Maintenance Decisions and Capital Planning Efforts. GAO 13-757.

OIG. 2012a. Contract Towers Continue to Provide Safe and Cost-Effective Services, but Improved Oversight of the Program Is Needed. AV-2013-009.

OIG. 2012b. The Success of FAA’s Long-Term Plan for Air Traffic Facility Realignments Depends on Addressing Key Technical, Financial, and Workforce Challenges. AV-2012-151. July 17.

OIG. 2013. FAA’s Controller Scheduling Practices Can Impact Human Fatigue, Controller Performance, and Agency Costs. AV-2013-120.

This study has examined whether the methods used by the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) in estimating staffing needs for air traffic controllers ensure the safe operation of the National Airspace System (NAS) in the most cost-effective manner. The committee considered the mathematical models used in generating the initial staffing targets and the staffing plan and how the plan is executed to ensure distribution of the intended number of staff to the right facilities. The effects of the Next Generation Air Transportation System (NextGen) and of current and estimated budgets and available funding on generation and execution of the plan were also considered.

This chapter summarizes the key insights from the detailed descriptions, findings, and recommendations provided in the preceding chapters. The chapter concludes with the committee’s major recommendations.

SAFETY AND CONTROLLER STAFFING

The first requirement of the air traffic control (ATC) system is to ensure safety. This requirement drives the key functions assigned to air traffic controllers. ATC has been identified as a causal or contributing factor in only a few aviation accidents, according to reports from the National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB). However, nationwide assessments of safety mask differences in accident rates across industry segments: most notably, the rate of ATC-related accidents1 for general aviation, although small, is about eight times that for commercial aviation (see Chapter 2). In addition, the committee’s relatively simple analysis indicated that loss of separation2 was not the most frequent cause of the few fatal ATC-related accidents between 1990 and 2012. In many of these accidents, including many involving general aviation, NTSB reports (see Chapter 2) indicate that aircraft were put in a hazardous situation by controllers’ failure to provide safety alerts, including weather alerts, terrain alerts, and minimum safe altitude warnings. The level of ATC staffing may be related to these accidents in terms of whether controllers’ workload allows them to deliver both the required safety alerts and the other safety-related services that they provide when circumstances permit. FAA recognizes that controller workload may limit the ability to provide these additional services (FAA Order 7110.65, Paragraph 2-1-1). In analyzing accident and incident reports, it may be worthwhile to examine whether controller workload may also limit or impede controllers’ ability to provide the required separation and safety alert services.

Furthermore, evidence indicates that fatigue—defined as a physiological state of reduced mental or physical performance capability—is a risk factor for errors and accidents in work of the type performed by air traffic controllers. Such work requires constant attention and is often

_____________

1 The rate of ATC-related accidents is defined as the number of ATC-related accidents per 10 million ATC operations.

2 For purposes of the committee’s analysis, loss of separation refers either to loss of separation between two aircraft in the air or on the ground or to loss of separation between an aircraft and a ground vehicle.

complex and demanding. The need for many ATC facilities to sustain operations 24/7 necessitates shift work, with associated disruption of controllers’ sleep patterns.

Rare but highly publicized incidents of controllers falling asleep on the job have drawn attention to the risks associated with controller fatigue. As a result of these incidents, night shifts with a single controller on duty are no longer permitted in most circumstances. Other prescriptive limitations on controllers’ work schedules and duty times (e.g., limits on number of hours worked in any 24-hour period, mandatory break and lunch periods during a shift) aim to mitigate the risks associated with controller fatigue. In 2011, the Article 55 Fatigue Risk Management Work Group, which included representatives from FAA and the National Air Traffic Controllers Association, issued a series of fatigue-related recommendations aimed at increasing the safety of the NAS and improving the health and well-being of the controller workforce. One recommendation led to the 9-hour rule, which requires controllers to have a minimum of 9 hours off duty preceding the start of a day shift.

FAA’s Fatigue Risk Management Group continues to investigate and assess fatigue-related hazards associated with controller staffing levels and practices, as well as mitigation strategies, but budget constraints associated with the sequester resulted in a dramatic curtailment of these efforts in 2013. The group no longer has the resources to ensure that policy changes are being enacted throughout the enterprise and are having the desired effect. In addition, operational facilities lack a scheduling tool capable of evaluating schedules (and adjustments to them) for their fatigue risk and suggesting fatigue mitigations. For these reasons, FAA is not achieving the full benefits of a fatigue risk management program.

The committee is concerned about shift schedules that contribute to fatigue. In particular, under the counterclockwise rotating 2-2-1 schedule, controllers work five shifts in less than four 24-hour periods, the last one being a midnight shift. The schedule compresses the workweek and allows controllers 80 hours off at the end of the rotating schedule. Although the schedule is popular among controllers, it likely results in severely reduced cognitive performance during the midnight shift because of fatigue. Other recent studies have suggested the potential for perverse side effects of the policies that have been implemented to date, such as controller responses to new schedules that can cause greater fatigue risk when factors such as peak-hour commuting times are taken into account.

FAA is contracting with the same vendor used by air navigation service providers (ANSPs) in other countries to implement a new scheduling tool, but the timeline of its implementation at all facilities is not fixed.3 As noted earlier in the report, the following are among the potential benefits of the sophisticated scheduling software:

• Providing a consistent basis for establishing work schedules that minimize or mitigate the safety risks associated with controller fatigue;

• Ensuring that diverse facilities are all capable of generating efficient schedules, particularly at larger facilities where economies of scale may be possible; and

• Providing a consistent basis for informing the development of staffing standards at FAA headquarters and the creation of work schedules at the facility level.

_____________

3 FAA’s target date for implementing the new scheduling tool at 15 facilities (the end of FY 2013) appears to have slipped.

In view of the limited understanding of the relationship between safety and staffing in general and the partial and unvalidated efforts being taken to address fatigue in particular, caution is needed before major changes in controller staffing levels or practices are implemented. Current staffing levels appear to ensure adequate safety, but FAA does not collect the information required for more detailed insights and data-driven decision making with regard to changes in controller staffing, including those associated with the transition to NextGen.

A better understanding of the relationship between safety and staffing can be fostered by involving controllers in discussions of staffing. Such discussions can both help ensure safety and involve the controllers in determining alternative staffing solutions. Addressing issues highlighted by controllers, for example through training or visible changes in policy, and providing prompt feedback to controllers about actions taken in response to their suggestions are important features of a strong safety culture. One mechanism for such discussions is the reporting of safety concerns by controllers via the Air Traffic Safety Action Program. However, FAA could not describe to the committee a coherent process for using these reports and other safety data to assess staffing, other than examination of fatigue concerns.

The safety of FAA’s ATC services depends not only on the performance of individual controllers but also on the agency’s collective safety culture. Effective communications founded on mutual trust are generally recognized as contributing to a positive safety culture. In the present context, the committee was concerned about the lack of transparency in controller staffing and scheduling decisions, sometimes to the point of appearing arbitrary. Attempts to foster reporting by controllers and participation by controllers in safety councils at both local and national levels are important aspects of safety culture, yet they place additional demands on controllers and must be supported by adequate staffing.

FAA’s PROCESS FOR ESTIMATING CONTROLLER STAFFING NEEDS

FAA uses a multistep process to determine the numbers of controllers needed to staff each of its ATC facilities in a given year. The process is described in Chapters 3 and 4 and summarized in the following sections. The desired controller staffing ranges for the coming year are given in annual updates to the agency’s controller workforce plan (see, for example, FAA 2013), together with information on the numbers of fully qualified and trainee controllers currently employed at each facility. The staffing ranges are used to develop FAA’s controller hiring plan for the coming year. The overall objective is to create a controller pipeline that ensures the availability of an appropriate number of controllers at each facility to meet forecast demand for services.

Traffic Forecasting

Forecasts of air traffic operations are inputs to the agency’s controller staffing standards and subsequent staffing and hiring plans. Forecasting air traffic operations accurately is a challenging task. For commercial aviation, for example, estimates of future passenger demand at individual airports need to be converted into numbers of aircraft operations on the basis of assumptions with regard to such items as airline fleets and load factors. Air traffic can suddenly decrease in response to unexpected events, such as the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks and the financial crisis of 2008–2009. Changes in air carrier operations can significantly affect local facilities. In

recent years, for example, airline mergers and network consolidations have resulted in reduced demand at airports in St. Louis, Missouri; Cincinnati, Ohio; and Memphis, Tennessee.

Since 2000, FAA has consistently forecast more air traffic operations than have materialized, often by significant margins. The forecasting models used are evolving and loosely documented. The impact of the overpredictions each year is muted by the fact that hiring plans are revised annually, so overhiring one year can in principle be rectified by reduced hiring in subsequent years, at least from a national perspective. However, overstaffing can be created at individual facilities that do not experience sufficient attrition to remedy staffing levels and result in a lasting impact.

Staffing Standards

FAA’s Office of Labor Analysis (ALA) generates staffing standards by using a sequence of mathematical models to estimate the number of position-qualified controllers required to meet the demands for air traffic services at each facility. The first mathematical model (on-position staffing model; see Figure 3-1) assesses the number of controllers needed on position at each facility to meet last year’s traffic demand in each 15-minute interval through representative days. The committee found that FAA’s mathematical models for terminal facilities [towers and terminal radar approach control (TRACON) facilities] are mostly reasonable for their purpose, as discussed in Chapter 3. The models relate key markers of the demands imposed by air traffic to requisite controllers’ activity in a comprehensible manner, and the results are substantiated and validated by operational data.

In contrast, the committee shares the concerns of an earlier committee report with regard to the model used in estimating the number of controllers required on position to perform traffic-driven tasks at en route facilities (TRB 2010). The earlier report criticized the methods used in deriving model parameters and in converting the modeled task load into estimates of the number of controllers needed. It recommended a series of actions aimed at improving and validating the model. FAA4 has made only limited progress in addressing the recommendations, and this committee is unable to report any significant improvement in the model to address the concerns articulated in the 2010 report. This committee had the broader charter of examining the entire staff planning process. In that context, the committee questions the approach of the task load model for en route facilities. Rather than representing higher-level tasks that can be observed and validated easily, this model attempts to represent many highly detailed cognitive activities. The level of detail is not commensurate with the model’s role in staffing standards generation, and validating all the model parameters and their collective output is costly and difficult. For the purposes of staffing estimates, which combine model outputs with expert judgment, a simpler model based on data that can be readily observed might prove more appropriate and cost-effective.

The second mathematical model (shift coverage model; see Figure 3-1) used in generating the staffing standards, a scheduler, was a cause of major concern for the committee. This model examines the time on position of certified controllers provided by the previous models in 15-minute increments throughout a range of representative traffic days. It generates schedules for work shifts for controllers, generally 8 hours long, on the assumption that all controllers are qualified to work all positions. To generate an effective staffing standard, the schedules should reflect day-to-day operational realities at the facilities, including constraints

_____________

4 The task load model for en route facilities was developed by MITRE Corporation under contract to FAA.

derived from FAA orders and the collective bargaining agreement with the National Air Traffic Controllers Association.5 For example, controllers may work a maximum of 10 consecutive hours in a shift and are required to have a 30-minute meal break within a specified window in the shift. The scheduler can, in principle, factor in these constraints, but it cannot apply constraints across shifts that start one day and finish the next (i.e., that cross midnight). The legacy scheduling model that FAA uses for estimating the numbers of controllers needed at each facility has several key limitations in its ability to include scheduling constraints. In contrast, ANSPs in other countries, including Australia, Canada, and Germany, have replaced their legacy scheduling tools with sophisticated software capable of incorporating all constraints while generating efficient controller schedules. FAA has contracted with the provider used by these other countries and is working to implement a similar scheduling tool, known as Operational Planning and Scheduling (OPAS). The intent is to use OPAS as a consistent basis for informing both the development of staffing plans at FAA headquarters and the creation of work schedules at individual facilities. FAA had planned to implement OPAS at roughly 5 percent of its facilities by the end of FY 2013 (OIG 2013), but this schedule has slipped to unspecified dates. OPAS is not yet being used as part of FAA headquarters’ staffing standards process.

The third mathematical model (daily staffing forecast model; see Figure 3-1) applied in generating the staffing standards scales the estimate of required controllers to manage the traffic forecast for the 90th percentile traffic day (i.e., the day when traffic levels are higher than on 90 percent of other days over the course of a year). This model incorporates traffic forecasts for the year (which can be 1, 2, or 3 years ahead) when hires made now can be trained and qualified into the facility.

The fourth, final mathematical model (availability factor model; see Figure 3-1) is simple: it scales the minimum workforce required for the scheduled shifts by a factor of 1.76. This is a reasonable and common method of accounting for the usual practice of working five shifts in a 7-day week and for required leave, vacation, and so forth.

The above models collectively apply two key assumptions or trade-offs. First, the choice of scaling the staffing standards to 90th percentile traffic is conservative. Other ANSPs are similarly cautious in their staffing estimates. Different choices would not substantially alter the estimated staffing levels but would change how often any facility could meet traffic demand. The committee’s analysis showed that staffing levels would increase by about 9 percent if the agency staffed to the busiest traffic day (the 100th percentile day, i.e., the facility would be expected to meet traffic demand at all times) and would decrease by about 8 percent if it staffed to the median traffic day (the 50th percentile day, i.e., traffic flow through the facility would need to be limited one-half of the time).

Second, the staffing models assume that all on-position traffic management tasks are performed by position-qualified controllers, some of whom may not be fully qualified [i.e., who may not be certified professional controllers (CPCs)]. In FY 2012, 13 percent of the required time on position managing traffic was performed by trainee (non-CPC) controllers under general supervision (as opposed to one-on-one on-the-job training). The impact of this assumption about the role of trainees on staffing estimates depends on the number of trainees in the workforce, which in turn should anticipate controller losses with enough lead time to train replacements. In FY 2012, about 23 percent of the workforce were not fully qualified in their facilities but contributed to managing traffic at positions for which they were qualified.

_____________

5 Some of the schedule constraints connected to the collective bargaining agreement are facility-specific.

Operational Input: Service Unit Input and Productivity Data

The staffing estimates derived by ALA [which is outside of the Air Traffic Organization (ATO)] are then averaged with operational data. Two inputs assess past productivity and peer productivity; outliers are ignored for these inputs.

The third input is service unit input (subject matter expert input), which helps to ensure that the calculated staffing ranges reflect each facility’s unique operational requirements. The methods used in generating this input are not well documented, but FAA appears to have made progress recently in clarifying the purpose of service unit input for experts in the field and in obtaining consistent and informed inputs from them. In some cases, mathematical models are used to capture a facility’s historical staffing in response to traffic in a clear and consistent manner, and the results are used as guideposts by field focus teams in establishing their service unit input values. However, this approach appears to be applied inconsistently, with many changes in the past year. For example, in the past en route facilities have used the staffing standard output as their service unit input (i.e., they have not treated the service unit input as an independent assessment of staffing needs from the field). In contrast, recent estimates by en route facilities—their own assessments of service unit input—have differed considerably from both the staffing standard outputs and the results of the En Route Validation Tool. The generation of service unit input is another aspect of the staff planning process that does not appear to have a consistent, established, and clearly understood basis and thus can appear to be an arbitrary adjustment to the mathematically generated staffing standard process.

STAFF PLANNING AND EXECUTION OF STAFFING PLAN

FAA uses the output from its staffing models to develop a staffing plan that specifies how many new hires and net transfers (transfers in minus transfers out), or staffing gains, each facility should receive. Efficient execution of this plan depends on the agency’s ability to select and train individuals who will go on to qualify as controllers in a timely manner and to use voluntary transfers of controllers from one facility to another to help reduce imbalances in staffing at specific facilities.6

One of the challenges FAA faces in assigning controllers to specific ATC facilities is the wide variation in the volume and complexity of traffic. Sending new FAA Academy graduates to the most demanding facilities has historically resulted in high failure rates, and this practice has now been largely discontinued. Even some fully qualified controllers are not well suited to the work at high-level facilities. Another consideration is that both trainee and fully qualified controllers require additional training when they arrive at a new facility. The latter are categorized as certified professional controllers in training (CPC-ITs) until they have been certified on all positions at the new facility and again achieve CPC status. Transferring controllers between facilities typically involves a lead time of at least 1 year as controllers recertify at the new facility. Therefore, transfers are not an immediate solution to problems of under- or overstaffing resulting from changes in demand for ATC services. Nonetheless, appropriate incentives for transfers, developed and agreed on by FAA and the National Air

_____________

6 Requests for transfers are initiated by controllers themselves, and FAA makes no attempt to persuade controllers to transfer to understaffed facilities or from overstaffed facilities to rectify staffing imbalances.

Traffic Controllers Association, could help the agency make more effective use of voluntary transfers in rectifying staffing imbalances.