The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) is a program of studies designed to assess the health and nutritional status of adults and children in the United States. NHANES is a major program of the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS), which is part of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and has the responsibility for producing vital and health statistics for the nation. The NHANES program began in the early 1960s and has been conducted as a series of surveys focusing on different population groups or health topics. In 1999, the survey became a continuous program that has a changing focus on a variety of health and nutrition measurements to meet emerging needs. NHANES is a cross-sectional survey of the U.S. household population with an annual sample size of approximately 5,000 individuals. These persons are located in counties across the country, 15 of which are visited each year.

Information is collected through in-person home interviews and health examinations at mobile examination centers. The NHANES interview includes demographic, socioeconomic, dietary, and health-related questions. The examination component consists of medical, dental, and physiological measurements, as well as laboratory tests administered by highly trained medical personnel. Findings from this survey are used to determine the prevalence of major diseases and risk factors for diseases. Information is used to assess nutritional status and its association with health promotion and disease prevention. NHANES findings are also the basis for national standards for such measurements as height, weight, and

blood pressure. Data from the survey are used in epidemiological studies and health sciences research, which help develop public health policy and design health programs and services for the nation. The NHANES Website (http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes.htm [June 2014]) has a large amount of information about the survey and related research and results.

In this session of the workshop, Kathryn Porter, NCHS, provided an overview of the NHANES. The overall goal of NHANES is to assess the health and nutritional status of children and adults in the United States. The survey focuses on chronic disease, on measures of environmental toxicants, and on diet and nutrition. Another goal of NHANES, which is the focus of the workshop and this summary, is to create and maintain a nationally representative specimen bank.

To obtain participant permission for specimen collection, NHANES uses a four-consent design as part of its continuous survey. There is consent for a household interview and a separate consent for physical examination. The interview and exam response rates have hovered around 75-77 percent, quite high for a health survey (Zipf et al., 2013). NHANES also asks for consent to store blood and urine for nongenetic future research and asks for a separate consent from participants aged 20 and over to store blood for future genetic research. The latter two consents state that the survey organization does not know what tests will be done on the specimens in the future and that participants will not be contacted with results. About 85-90 percent of adults who agree to the exam also agree to allow NHANES to store specimens for genetic research (McQuillan, Pan, and Porter, 2006).

The NHANES staff processes a wide range of specimens, which are sent to 24 laboratories across the country and become the basis of more than 500 assays. Relatively few of these are reported back to participants, namely, only those that have clinical relevance to participants. Participants receive a final report with a preset number of findings in 12 to 16 weeks after the exam and are urged to discuss results with their doctors. If participants want help on how they should follow up on a condition, or about finding an appropriate clinic, referrals are provided. NHANES does not cover any of the costs of follow-up.

As Porter explained, NHANES seeks to report findings that are valid and obtained by a CLIA-certified laboratory.1 Reportable findings should have significant implications for a participant’s health concerns, and a course of action to ameliorate or treat the concerns should be readily available, both of which are in line with recommendations from the Presi-

__________________

1CLIA refers to regulations established by federal Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments; see http://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Legislation/CLIA/index.html?redirect=/clia/ [June 2014].

dential Commission for the Study of Bioethical Issues (see http://www.bioethics.gov [June 2014]). Survey participants always have the option to opt out; that is, to say that they do not want to receive any such results. A very small percentage of participants actively opt out.

NHANES DNA specimens have been banked since 1991 and are physically stored at the CDC in Atlanta. From various cycles of NHANES, about 26,000 individuals have given permission to store their specimens in the DNA bank. Data are held within the CDC for confidentiality purposes. No genomic results are allowed into the public domain.

The DNA bank was opened to researchers in 1999 after considerable effort to establish procedures for releasing specimens to researchers while maintaining confidentiality protections promised by law. It was decided that researchers could not investigate genes with clinical relevance because NCHS does not have the capability of providing genetic counseling. Hence, the agency only accepted research proposals that involved candidate genes; that is, single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) of interest. NCHS could critically review these proposals and determine if those SNPs were reportable or not. Most approved research requests involved common gene variants with relatively low associated risk.

As time and science marched on, Porter said, two things changed. First, technology evolved and targeted gene analysis was no longer the standard. NCHS began to receive proposals for genome-wide association studies (GWAS) done with chips with millions of SNPs. Such studies may generate incidental findings, and the question arose as to how potentially reportable gene variants would be handled. The second change involved an evolving ethical context. There was increasing recognition among investigators, institutional review board (IRB) members, and bioethicists that blanket nondisclosure of individual research results and/or incidental findings may be inappropriate in public health research. The acceptability of the NHANES nondisclosure agreements that participants signed in the past came into question.

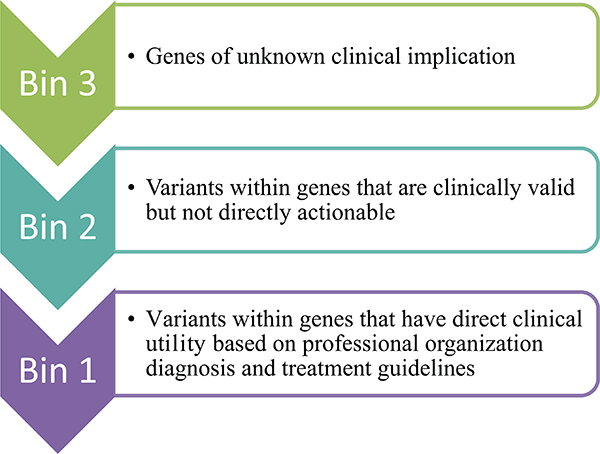

The NHANES program consulted with review boards and ethicists about how to proceed, and the upshot, Porter explained, was the concept of “binning” the genome, shown in Figure 2-1. Gene variants could be sorted into buckets or bins, with Bin Three having genes of unknown clinical implication and Bin Two containing variants within genes that are clinically valid but not directly actionable. The consensus was that NHANES would not have to act on or report back on items in Bins Two and Three.

Bin One contains variants within genes that have direct clinical utility and for which there are treatment guidelines. The NHANES consultative process recommended that Bin One variants should be reported to participants (Berg, Khoury, and Evans, 2011). This approach was presented

FIGURE 2-1 Binning the genome.

NOTE: An NHANES consultative process recommended that only Bin 1 variants should be considered for reporting.

SOURCE: Adapted from Berg, Khoury, and Evans (2011).

to the NCHS Board of Scientific Counselors, which then called for wider input on how to proceed, not only with regard to NHANES but also because this has become an important issue for many population-based studies.