ORGANIZATION AND RESPONSIBILITIES

While the mission of the U.S. Army is “to fight and win our Nation’s wars,” the organization for carrying out this mission has varied over the 239-year history of the Army.1 In 1947, following the end of the Second World War, the defense establishment was reorganized: Two cabinet-level departments (War and Navy) became the Department of Defense, headed by a Secretary of Defense who “is the principal assistant to the president in all matters relating to the Department of Defense. Subject to the direction of the President and…the National Security Act of 1947…[who] has the authority, direction and control over the Department of Defense.”2 The National Security Act of 1947 also established the Departments of the Army, the Air Force, and the Navy, and the Reserve components of the defense establishment. The 1986 Goldwater-Nichols Department of Defense Reorganization Act (Public Law 99-433) standardized many provisions of the earlier acts and provided for uniform statutory authorities for the military departments. The Reserve Officer Personnel Management Act (enacted as Title XVI of Public Law 103-337, the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 1995) established the responsibilities of the Reserve components. These laws also established the Joint Chiefs of Staff and the combatant commands,3 which serve as the operational elements of the department and carry out those missions assigned to them by the Secretary of Defense.

Under Title 10, the Secretaries of the Departments, subject to certain exceptions, shall “assign all forces under their jurisdiction to unified and specified combatant commands…” and “subject to the authority, direction, and control of the Secretary of Defense and subject to the authority of commanders of the combatant commands under section 164(c) of [Title 10] “[be] responsible for the administration and support of forces assigned by him to a combatant command.”4 In practical terms, the military departments have responsibilities to organize, train, and equip the forces they assign to the combatant commands, subject, however, to the instructions of the Secretary of Defense and, for certain activities, the combatant commanders.5

________________________

1 U.S. Army mission information available at Cloud.cio.gov, “U.S. Army,” http://cloud.cio.gov/profile/us-army, accessed August 28, 2014.

2 Title 10 USC, Chapter 2, Section 113, paragraph b.

3 The combatant commands are Africa Command, Central Command, European Command, Northern Command, Pacific Command, Southern Command, Special Operations Command, Strategic Command, and Transportation Command.

4 Title 10 USC, Chapter 6, Section 165, paragraph b.

5 Title 10 USC, Chapter 303, Section 3013, paragraph b, indicates that “Subject to the authority, direction, and control of the Secretary of Defense and subject to the provisions of chapter 6 of this title, the Secretary of the Army is responsible for, and has the authority necessary to conduct, all affairs of the Department of the Army, including the following functions: (1) Recruiting. (2) Organizing. (3) Supplying. (4) Equipping (including research and development). (5) Training. (6) Servicing. (7) Mobilizing. (8) Demobilizing. (9) Administering (including the morale and welfare of personnel). (10) Maintaining. (11) The construction, outfitting, and repair of military equipment. (12) The construction, maintenance, and repair of buildings, structures, and utilities and the acquisition of real property and interests in real property necessary to carry out the responsibilities specified in this section.”

Title 10 also indicates that, “unless otherwise directed by the President or the Secretary of Defense, the authority, direction, and control of the commander of a combatant command with respect to the commands and forces assigned to that command include the command functions of— (A) giving authoritative direction to subordinate commands and forces necessary to carry out missions assigned to the command, including authoritative direction over all aspects of military operations, joint training, and logistics [emphasis added].”6

LOGISTICS OPERATIONS AND PLAYERS

Today’s battlespace logistics operations are typically carried out in a Joint environment under the direction of the combatant commanders. The services normally provide the support required for their forces assigned to the combatant commanders. The Defense Logistics Agency provides “subsistence, bulk fuel, construction and barrier materiel, and medical material…spares and reparables for weapons systems…[and] manages a global network of distribution depots that receives, stores, and issues a wide range of commodities owned by the Services, General Services Administration, and DLA”(JCS, 2013, p. I-7). The U.S. Transportation Command provides “air, land, and sea transportation, terminal management, and aerial refueling to support the global deployment, employment, sustainment, and redeployment of US forces” (JCS, 2013, p. I-7). Logistics (supplies and service) support is also provided in the theater of operations through contractor logistics support under authorities of the combatant commanders.

The Army’s specific logistics responsibilities include supplying, equipping (including necessary research and development), maintaining, outfitting, and repairing military equipment and ammunition needed by and used by the Army and other U.S. and coalition forces as ordered. The Army Material Command has the mission for the Army to “develop and deliver global readiness solutions to sustain Unified Land Operations, anytime, anywhere.”7 Logistics organizations and contractors, within the Army Materiel Command and as part of tactical formations, carry out the logistics missions. The Combined Arms Support Command (CASCOM) of the Army Training and Doctrine Command is responsible for training, educating, and growing adaptive sustainment professionals and developing and integrating innovative Army and Joint sustainment capabilities, concepts, and doctrine to enable unified land operations.8

Logistics in Joint and Combined Operations

In the future, U.S. forces must be prepared to conduct a range of military activities, including combat, security, engagement, and relief and reconstruction operations. These will be conducted across multiple domains, including air, land, sea, space, and cyber. It is anticipated that future operating environments will be characterized by increasing uncertainty, rapid change, extreme complexity, and persistent conflict. The Department of Defense (DoD) must be adaptive and agile to meet the diverse needs of the Joint force commanders at the pace at which new threats evolve. An elevated level of Joint supply support will be needed to integrate the capabilities of many new partners while also satisfying the requirements of multiple missions.

The 2014 Quadrennial Defense Review emphasizes the need to rebalance and reform across the defense enterprise to meet the security challenges of the future during a “period of fiscal austerity” (DoD, 2014). The review builds on the National Security Strategy and the 2012 Defense Strategic Guidance

________________________

6 Title 10 USC, Chapter 6, Section 164, paragraph c.

7 U.S. Army Materiel Command (AMC) information is available at http://www.amc.army.mil, accessed April 27, 2014.

8 U.S. Army Combined Arms Support Command (CASCOM) information is available at http://www.cascom.army.mil, accessed April 27, 2014.

(DoD, 2012), emphasizing three pillars: protect the homeland, build security globally, and project power and win decisively. To achieve these objectives, the review calls for increased innovation—not just in technology but also with respect to how U.S. forces operate and work with other U.S. departments and agencies and with international partners. Central to this innovation is shaping, preparing, and posturing the Joint force to sustain U.S. leadership in this rapidly changing security environment.

Thus, in the future, it is anticipated that the Army will be operating in a complex, widely distributed, Joint and coalition operational environment. Some thought has already been given to this. The Capstone Concept for Joint Operations: Joint Forces 2020, dated September 10, 2012, describes the anticipated future security environment (JCS, 2012). It characterizes this environment as rapidly changing, uncertain, complex, increasingly transparent, and with a range of increasingly capable enemies. The capstone concept articulates a vision of how the future force will operate to protect U.S. national interests. The capstone concept proposes the concept of globally integrated operations, in which Joint Force elements, globally postured, combine quickly with each other and mission partners to integrate capabilities fluidly across domains, echelons, geographic boundaries, and organizational affiliations.

The Capstone document envisions the integration of existing and emerging capabilities with new ways of fighting and partnering, and identifies eight key elements of globally integrated operations (JCS, 2012):

• Commitment to mission command;

• Seize, retain, and exploit the initiative;

• Global agility;

• Partnering;

• Flexibility in establishing Joint forces (i.e., mission-based command versus strictly geographically based command);

• Cross-domain synergy;9

• Use of flexible, low-signature capabilities (such as cyberspace, space, special operations, global strike, intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance); and

• Increasingly discriminate to minimize unintended consequences.

The document identifies implications for Joint Force 2020 tied to key warfighting functions of command and control, intelligence, fires, movement and maneuver, protection, sustainment, and partnership strategies, with partnership strategies being introduced as equivalent to the traditional warfighting functions. In August 2010, recognizing the challenges expected in the future operating environment, the Joint Staff, J-4 published the Joint Concept for Logistics (DoD, 2010). This concept document emphasizes the need for increased integration and synchronization of Joint logistics processes within the Joint logistics enterprise in order to provide support for Joint force commanders across a range of military operations.

The U.S. Special Operations Command (SOCOM) was legislated into existence by Congress in 1987 in an attempt to correct some of the deficiencies that became apparent during the failed Iranian hostage rescue attempt of 1980. This legislation directed the secretaries of the military departments to transfer operational control of their existing special operations forces (SOF) from their respective service chiefs to SOCOM. As part of this legislation, Congress also granted SOCOM a number of military department-like authorities, including specific budget authority to develop, acquire, field, and maintain special operations-peculiar capabilities; authority to perform acquisition and procurement activities

________________________

9 Cross-domain synergy is defined as “the complementary vice merely additive employment of capabilities across domains in time and space” (JCS, 2012, p. 7).

(including contracting); and authority to conduct test and evaluation (T&E) activities. Therefore, in addition to being a combatant commander, the commander of SOCOM also functions as both a service chief (i.e., organize, train, and equip SOF) and as the equivalent of the head of a military department, including the functions discussed above.

In the service chief-like role, the SOCOM commander oversees a force composed of the Army Special Operations Command (approximately 26,000 personnel), the Air Force Special Operations Command (approximately 17,000 personnel), the Naval Special Warfare Command (approximately 7,000 personnel), and the Marine Corps Forces Special Operations Command (approximately 3,000 personnel), plus the Joint Special Operations Command, the SOCOM Headquarters organization, the Joint Special Operations University, and the Special Operations Command-Joint Capabilities organization. The mission of the last-named organization, which is to train conventional force and SOF staffs in the proper integration and employment of SOF when combined with conventional forces, was transferred to SOCOM upon the disestablishment of the U.S. Joint Forces Command in 2011.

There are notable differences between the SOCOM commander and a service chief. The reporting chain is different. The SOCOM commander reports directly to the Secretary of Defense and the President of the United States rather than to the secretary of a military department. The SOCOM commander is authorized to approve formal operational requirements (ORs). Following approval, these SOF ORs are submitted to the Joint Requirements Oversight Council for awareness and information, whereas the council is the review and approval authority for ORs from the individual services. Although the SOCOM commander oversees and monitors personnel administration of the special operations force, SOCOM reimburses the respective services for actually paying and managing each service’s SOF personnel within their respective service personnel systems. There are also specific agreements, negotiated as part of the original transfer of operational control, with each military department and/or service to provide service common equipment and specific logistics and sustainment support for their respective SOF personnel and units.

As the equivalent of the head of a military department, the SOCOM commander has several important sets of authorities and associated assets to fund, develop, outfit, maintain, and sustain the desired SOF capabilities. These include

• Budget authority, a dedicated funding line, called the Major Force Program (MFP) 11, and a headquarters comptroller staff;

• Acquisition and procurement authorities, a headquarters acquisition staff consisting of an acquisition executive, program executive officers, program managers, logisticians (including a J-4 organization with data links to the respective military department and service databases), and a procurement staff (contracting officers and associated counsel) located at headquarters and in the component commands; and

• T&E authority (it can either perform T&E in-house using SOCOM assets or outsource the T&E to any of the respective Service or DoD T&E activities).

As a designated combatant commander, the SOCOM commander has two main roles according to the Unified Command Plan:

• Synchronizing DoD’s planning for global operations against terrorist networks as well as executing global operations against terrorist networks as directed; and

• Providing SOF support to the other combatant commanders in response to their respective formal requests for forces, and also to the U.S. ambassadors and their respective country teams.

Each geographic combatant command has a Theater Special Operations Command (TSOC) component as part of its staff. Once SOF units and capabilities are assigned to a geographic combatant command in response to a request for forces, they become an organizational part of the TSOC, which reports directly

to that geographic combatant commander. The requesting combatant commander is then responsible for utilizing them operationally and, among other things, for providing all their associated logistics and sustainment support. Such support requirements can range from situations such as Operation Iraqi Freedom (OIF) and Operation Enduring Freedom (OEF), where large numbers of SOF were operating in conjunction with large numbers of conventional forces, to situations where there have been very small numbers of SOF operating in over 70 countries.

ASSESSING THE LOGISTICS BURDEN

The wars in Afghanistan and Iraq have been unlike those that occurred under more conventional circumstances. While the initial phase of OIF was more conventional, that is, units in formations engaging other military units over a several-week period, the remainder of the war became a mix of asymmetrical, unconventional war and short periods of conventional urban warfare. The war in Afghanistan has been unconventional since its beginning and provided few opportunities for formations to engage in combat of the kind that occurred in the past. In both Iraq and Afghanistan, the length of war was exceptional. As a result, over time the support base for much of the U.S. and coalition forces grew to embody logistics support conditions similar to those found in the United States or a partner country away from the combat zone. In both countries, the lines of supply, both air and land, were extensive and involved heavy support from contractor personnel. Box 2-1 discusses base camps in Iraq and Afghanistan.

Because U.S. forces were used in roles they were not equipped or trained for in both OEF and OIF—for example, artillery and other units were carrying out transportation security missions—and the operations over time involved individual battles, with each battle having a different supply character, it is difficult to develop insights into what future logistics burdens might be based on what has occurred over the past 13 years. It is clear that there was a continuous, heavy logistics burden on the system in both Iraq and Afghanistan, but whether or not the demands that characterized these wars will be seen again in future wars is hard to say.

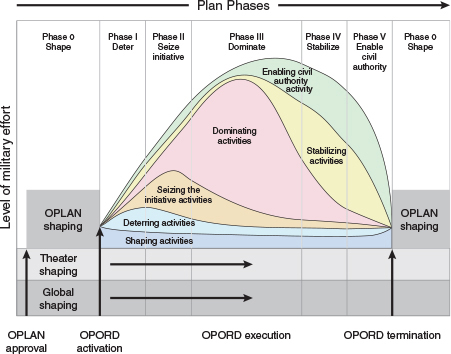

Joint Chiefs of Staff Joint Publication 3-0, Joint Operations, defines six phases of military operations and relates these phases to the level of military effort expended in each (Figure 2-1) (JCS, 2011). The greatest amount of effort and the most time are expended in either the domination phase or for activities related to direct combat operations. However, in both OEF and OIF, the majority of the time in which U.S. forces were and continue to be engaged falls into Phase IV or V. Unlike Desert Storm and Desert Shield, during which U.S. forces entered the area of operation, conducted operations, and returned to their base stations, the initial U.S. force buildup for the conduct of the domination operations in OIF and OEF was followed by continuing expansion of the base support activities needed to carry out the subsequent phases. As a result, what began as a domination mission turned into long-term stability operations requiring support more typical of that found in locations where United States has determined that it will have a long-term presence (e.g., Korea, Japan, and Europe during the Cold War). In OIF and OEF, combat operations were and still are being conducted on a daily basis from within a structure that integrates long-term base support operations, host nation support capabilities, and continuous expeditionary military operations.

As with operations in Vietnam, the presence of these large base camp facilities created not only the demand for logistics support of the bases themselves and the forces necessary to secure these bases but also an expectation that deployed elements would receive a higher level of support during military operations than was expected or provided during expeditionary operations such as Operations Desert Storm, Urgent Fury (Grenada), and Just Cause (Panama). As a result, much of the understanding of logistics in support of combat operations by all ranks of today’s Army has been conditioned by experiences with a nonstandard, base-centric support activity. Although the supplies required for OIF and

BOX 2-1

Base Camps in Iraq and Afghanistan

Base camps, forward operating bases, and similar facilities have been part of the landscape of OIF and OEF. During OIF, bases developed from initial positions of combat units as they moved into key areas of Iraq following the 2003 invasion by U.S. forces. Once it was determined that the forces would be remaining in the area for a substantial period of time, military construction elements and contractor forces began to convert expeditionary field bases into more static facilities. As the size of the forces increased so did that of the base. As the necessity for increased support grew or standards were improved, the bases also grew in size and complexity. To promote efficiencies, activities were consolidated where possible into larger and larger facilities such as common dining facilities, recreational activities, exchanges, fast food services. As the threat of mortar and rocket attacks on the bases grew, efforts were put into increasing the protection for facilities from such attacks. As it became possible and feasible, for example, as facilities for electric power generation were constructed, the standards at many facilities improved, to include, for instance, air conditioning. By the end of OIF and the peak of OEF, standards at many of these camps and facilities approached those found at some U.S. and overseas military installations. By the end of U.S. activity in OIF, considerable effort and support were focused on the operation and security of the bases as opposed to direct support of combat operations. The combined size of Camp Leatherneck (a U.S. base camp) and Camp Bastion (a U.K. base camp) in Helmand Province, Afghanistan, approached 10 square miles (7,000 acres), and they housed, at their peak, more than 40,000 troops.

FIGURE 2-1-1 Aerial view of the hospital at Bagram Airfield in Afghanistan.

SOURCE: http://www.globalsecurity.org/jhtml/jframe.html#http://www.globalsecurity.org/military/world/afghanistan/images/bagramhospital_aerial_17oct2002.jpg.

FIGURE 2-1 Phases of a notional operation plan versus level of military effort. OPLAN, operation plan; OPORD, operation order. SOURCE: JCS (2011).

OEF are difficult to quantify, a significant portion of them were and are directly related to the existence of the bases out of which the forces operate as opposed to what would have been needed had the forces been operating in an expeditionary-like environment (e.g., Desert Storm).

Recognizing that planning figures for logistics demands during combat operations could not be tied to the theater demands seen in OIF and OEF, in 2008 CASCOM conducted an air-ground distribution Computer Assisted Map Experiment (CASCOM, 2008). CAMEX 2008 used the Multi-Level One Scenario, which is intended for planning and map experiments. It is a corps-level U.S. Army Training and Doctrine Command standard operational scenario based in the year 2007 and built for the purpose of testing future concepts (e.g., operational or sustainment concepts) and equipment. CAMEX 2008 represents CASCOM’s examination of the operational challenges of routine sustainment for the force in 2016. It was used to identify shortfalls in the tactical distribution system by laying out daily resupply tonnages by supply class against the capability of the distribution system to deliver these tonnages to a heavy brigade combat team (HBCT) and a fires brigade (FIB). The distribution lines of communications in CAMEX 2008 ran from the aerial port of debarkation to the brigade support area and then to the forward support company in the HBCT and FIB. Direct distribution and resupply from the aerial port of debarkation to the forward support company was also explored in CAMEX 2008. The CAMEX 2008 report also breaks out the required daily C-130 sustainment sorties for an HBCT and a FIB. Table 2-1 shows the daily resupply requirements for an FIB and an HBCT. Tables 2-2 and 2-3 show the 4-day sustainment requirements for an HBCT and an FIB and shows the proportion of those requirements delivered via ground transport and the proportion by air. Table 2-4 shows the total distribution of sustainment cargo over the course of CAMEX 2008 and the proportion of those requirements that was delivered via ground transport and what proportion by air.

TABLE 2-1 Daily Resupply Requirements for a FIB and HBCT from CAMEX 2008 (tons)

| Supply Class | Description | FIB | HBCT | Subtotal | |

| Class I | Rations | 12.08 | 23.20 | 35.28 | |

| Class II | Clothing and textile | 2.36 | 4.53 | 6.88 | |

| Class III | Package petroleum | 1.11 | 2.14 | 3.25 | |

| Class III | Fuel | 121.61 | 338.24 | 459.85 | |

| Class IV | Barrier materials | 3.33 | 6.40 | 9.72 | |

| Class IV | Construction materials | 2.84 | 5.45 | 8.29 | |

| Class V | Ammunition | 175.93 | 45.24 | 221.18 | |

| Class VI | Personal demand | 0.51 | 0.98 | 1.48 | |

| Class VII | End items | 6.22 | 11.95 | 18.17 | |

| Class VIII | Medical supplies | 0.21 | 0.41 | 0.62 | |

| Class IX | Repair parts/batteries | 3.22 | 6.18 | 9.40 | |

| Ice | 6.35 | 12.20 | 18.55 | ||

| 1.66 | 3.20 | 4.86 | |||

| Water | 126.72 | 243.38 | 370.10 | ||

| Total | 464.15 | 703.47 | 1,167.63 | ||

| Delivered by GLOC, class IIIB, class I (water) and ice | 254.68 | 593.81 | 848.49 | ||

| Delivered by air | 209.47 | 109.66 | 319.13 | ||

NOTE: GLOC: ground lines of communication. SOURCE: CASCOM (2008).

TABLE 2-2 Four-Day Sustainment Requirements for an HBCT and How the Required Cargo Was Delivered

| Dry Cargo (tons) | Liquid Cargo (gallons) | |

| Four-day requirement | 438.6 | 363,848 (JP8) 234,580 (water) |

| Not delivered | 0.0 | 34,362 water |

| Delivered by air | 229.0 | 43,200 (JP8) 2,878 (water) |

| Delivered by ground | 209.6 | 354,729 (JP8) 214,467 (water) |

SOURCE: CASCOM (2008).

TABLE 2-3 Four-Day Sustainment Requirements for a FIB and How the Required Cargo Was Delivered

| Dry Cargo (tons) | Liquid Cargo (gallons) | |

| Total four-day requirement | 837.9 | 136,204 (JP8) 121,136 (water) |

| Total not delivered | 0.0 | 18,230 water |

| Total delivered by air | 831.9 | 26,400 (JP8) |

| Total delivered by ground | 6.0 | 116,658 (JP8) 103,304 (water) |

SOURCE: CASCOM (2008).

TABLE 2-4 Total Sustainment Requirements Over CAMEX 2008 and How Those Requirements Were Delivered

| HBCT | FIB | ||||||

| Dry (tons) | JP8 (gal) | Water (gal) | Dry (tons) | JP8 (gal) | Water (gal) | ||

| Four-day total | 438.6 | 397,929 | 233,477 | 837.9 | 143,058 | 121,534 | |

| Amount not delivered | 0 | 0 | 16,132 | 0 | 0 | 18,230 | |

| Total delivered | 438.6 | 397,929 | 217,345 | 837.9 | 143,058 | 103,304 | |

| Delivered by air | 229.0 | 43,200 | 2,878 | 831.9 | 26,400 | 0 | |

| Delivered by ground | 209.6 | 354,729 | 214,467 | 6.0 | 116,658 | 103,304 | |

| Percent by ground | 47.8 | 89.1 | 98.7 | 0.7 | 81.5 | 100 | |

| Percent by air | 52.2 | 10.9 | 1.3 | 99.3 | 18.5 | 0 | |

SOURCE: CASCOM (2008).

It should be noted that the HBCT modeled in CAMEX 2008 consisted of two maneuver battalions. The new HBCT design has three maneuver battalions. This can be expected to affect resupply requirements proportionally. Also, CAMEX 2008 did not provide explicit data on the logistics demand of Army aviation assets. It should also be noted that CAMEX 2008 assumed an already fully deployed force. The picture might be very different if the scenario included deploying the force to the operating theater.

As the Army moves toward 2020, it must either accept the heavy logistics burden shown above for more conventional warfare, assume that future warfare will not require that same amount of support, or take steps to ensure that, no matter the nature of the warfare, logistics requirements are reduced to a practical minimum to enable future forces to be efficiently and effectively supported with the supplies needed to win the wars they must fight.

As the Army moves into the next decades, it will likely be dealing with conflicts far different from those it dealt with since 9/11. Both the Marine Corps and the Army now speak in terms of expeditionary missions and expeditionary forces. This is in contrast to the experience in the last decade of conducting operations from fixed, mature bases. Getting to the battle site as quickly as possible and concluding whatever mission is assigned to the Army as fast as possible is paramount. This new approach is made all the more difficult by the global nature of the conflicts and potential conflicts that have emerged. The distances involved in Pacific operations are extraordinary and will stress every facet of logistics for all services. At the same time, force structure and resources are being reduced, and there is little certainty as to how far the tightening and resource reductions will go. It is a matter of having to do more with less.

For the past 13 years, the Army has been engaged in a hybrid warfare scenario. In Iraq the conflict began with nearly conventional warfare, moved to fierce fighting in an urban environment, and then engaged in efforts to provide stability to a nation in turmoil. In Afghanistan, the mass of a conventional conflict was bypassed as entering forces began warfare in urban environments and stability operations. In both cases logistics began with support of frontline military operations and transitioned over time to a logistics structure that closely paralleled, in many respects, the massive system that existed in support of U.S. forces in Europe during the Cold War and coalition forces during the war in Vietnam. A significant part of the U.S. and coalition forces was committed to supporting logistics and supporting those who were providing logistics.

Now, the Army is moving into a new, more austere and more Joint environment and must prepare its personnel, its force structure, its decision-making support, and its concepts of operation for a more expeditionary approach. Logistics must be a central element of this preparation. There is no logistics silver bullet. Success will depend on full use of the potential of numerous technological and organizational opportunities that are now presenting themselves to the Army. The Army must recognize these opportunities and act upon them. This committee is concerned that all too often, logistics is addressed after everything else has been considered.

CASCOM (U.S. Army Combined Arms Support Command). 2008. Air-Ground Distribution Computer Assisted Map Exercise (CAMEX). Fort Lee, Va.: ATCL-BL.

DoD (Department of Defense). 2010. Joint Concept for Logistics. Washington, D.C.: Department of Defense.

DoD. 2012. Sustaining U.S. Global Leadership: Priorities for 21st Century Defense. Washington, D.C.: Department of Defense.

DoD. 2014. Quadrennial Defense Review 2014. Washington, D.C.: Department of Defense.

JCS (Joint Chiefs of Staff). 2011. Joint Publication 3-0, Joint Operations. Washington, D.C.: Department of Defense.

JCS. 2012. Capstone Concept for Joint Operations: Joint Forces 2020. Washington, D.C.: Department of Defense.

JCS. 2013. Joint Publication 4-0. Washington, D.C.: Department of Defense.