2

Overview of Issues Involved in Creating

Better Discharge Instructions

The workshop’s first panel, featuring three speakers, provided background information that would inform the subsequent two panels and the discussions that followed. Joshua Seidman, an independent consultant to the Brookings Accountable Care Organization Learning Network, provided an overview of why rules and regulations about discharge and after-visit summaries were developed and the implications of such policies. Alex Federman, associate professor of medicine at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, discussed what is known about current discharge and after-visit summary materials, and Darren DeWalt, associate professor of medicine at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, addressed the links between discharge and after-visit summaries that are constructed in a health-literate manner and improved outcomes.

DISCHARGE INSTRUCTIONS AND HEALTH LITERACY: POLICIES AND THEIR IMPLICATIONS1

It is always important, said Joshua Seidman, to think about health literacy in the context of understanding what people say and what people hear, let alone what they remember. He noted that research suggests that 40–80 percent of the medical information communicated by health care practitioners in the doctor’s office is completely forgotten by the time

_______________

1This section is based on the presentation by Joshua Seidman, independent consultant to the Brookings Accountable Care Organization Learning Network, and the statements are not endorsed or verified by the Institute of Medicine (IOM).

the patient gets home and that half of the information is recalled incorrectly (Kessels, 2003). In most instances, this failure to communicate is not because the patient is illiterate or unintelligent but because of a mismatch between the background of the person presenting the material and the one receiving it. “I think it is important to understand that information that is being imparted is very much related to someone’s background, someone’s context,” said Seidman.

The discharge planning requirements of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) include educating patients and caregivers about postfacility plans. These plans, which are required at discharge from acute care facilities, long-term care facilities, and rehabilitation hospitals, must include written and verbal instructions on postdischarge options, what to expect after discharge, and what to do if issues arise. CMS regulations also require that there be an evaluation of the patient’s and caregiver’s understanding of needs, though the regulations do not spell out how to evaluate that understanding or how to ensure that that understanding is meaningful. Seidman noted that it is challenging to figure out how to meet those requirements.

Five years ago, the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act created the meaningful use of electronic health records (EHRs) requirement as an incentive to adopt electronic health records and to do so in a way that would be meaningful to the health care system and patients. Seidman explained that the meaningful use requirements included four items relevant to the topic of this workshop. First, patients are entitled to electronic discharge instructions if they want them. Second, patients must be provided with an after-visit summary at the end of every outpatient visit to help address the fact that they forget 40–80 percent of everything they hear in the doctor’s office by the time they get home. Also required are patient reminders that are relevant not just to preventive care, such as cancer screenings and immunizations, but also to follow-up care. Patients are also supposed to receive patient-specific educational resources to help put the conveyed information into a context that, together with education, would improve health literacy.

In an ideal world, said Seidman, discharge instructions and patient-specific educational resources would account for the language that a patient speaks and whether the patient prefers to receive information in writing, in graphical forms, or even as links to video or audio clips delivered via a mobile device such as a cell phone or tablet. Under provisions of the second stage of the meaningful use requirements, which take effect in 2014, patients are entitled to view, download, and transmit this information and any information in the electronic health record into a form that they find most useful. “But that does not necessarily mean that they are going to understand that information,” said Seidman. He added that some organi-

zations, such as Healthwise and Krame’s, spend a great deal of time thinking about how to make the information mandated by the meaningful use requirements understandable to patients, caregivers, and the like.

The meaningful use provisions also mandate that a certain percentage of patients must actually go online and view, download, or transmit this information. “Just making information available does not mean that it is actually used,” said Seidman. “It may even be almost a big secret that this information is available or that you can get your discharge instructions electronically,” he explained.

One provision of the meaningful use requirements that is particularly germane to this workshop, said Seidman, pertains to the transition of care summary exchange that is designed to ensure that transitions of care summaries are shared among a patient’s many providers. This provision, he explained, “lays the groundwork for further expectations in the future around what shared care plans should be.”

To conclude his presentation, Seidman listed some difficult questions that he hoped would stimulate further discussion. The questions included

- What are the biggest policy levers that CMS can use to encourage care providers to do better with their discharge instructions?

- How much “policy” should be driven by the public versus private sectors, and in the public sectors, what is the right balance between federal and state policy levers?

- What is the right balance between ensuring activity is more than “check the box” versus being overly prescriptive, which could stifle innovation?

The last question, he noted, continues to challenge policy makers.

INPATIENT AND AMBULATORY DISCHARGE SUMMARIES2

Noting that little research has been conducted on discharge instructions, Alex Federman discussed two of the few studies on physician-to-patient communication that he was able to find in the literature. The first study examined the use of EHR-integrated treatment cards in a hospital in Geneva, Switzerland (Louis-Simonet et al., 2004). These treatment cards were a tool derived from an EHR that had been modified to enable clinicians to put in patient-specific medications using a series of drop-down menus. When patients were discharged, clinicians would use the cards as

_______________

2This section is based on the presentation by Alex Federman, associate professor of Medicine at the Ichan School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, and the statements are not endorsed or verified by the IOM.

prompts and as something that the patients could take with them when they left. In this study, patients who were exposed to the cards and received counseling using the cards were compared 1 week after initially receiving their discharge instructions with patients who did not receive the cards. The results showed that patients who received the cards were able to identify the purpose of their medication, the precautions they needed to take when using the medication, and the potential side effects. “This is not a mind-blowing study by any means,” said Federman, “but it does indicate that with counseling and a simple set of instructions about medications, patients will remember some of this information better than if they don’t receive such instructions. It points to the potential value of a document that a patient can walk away with after care.”

The second study he described was a qualitative examination of discharge summaries from emergency departments (Buckley et al., 2013). The investigators addressed eight patient-identified items that might be missing from discharge instructions:

- Define complex words and concepts with precise terms.

- Present a contextual framework and motivational information that would clearly state the implications of not following the discharge instructions.

- Provide specific, practical information with examples that are meaningful to the patient’s everyday experiences.

- Clarify uncertainty and manage expectations about how their condition might evolve after therapy.

- Provide visual aids and pictographs to illustrate key concepts.

- Address inappropriate but common practices and beliefs.

- Use a logical flow of information.

- Emphasize key points using typography (bold versus normal font, for example).

Using an after-visit summary from his own institution that was generated by a widely used commercial EHR system, Federman discussed some of the issues with discharge instructions. First, he noted that the discharge instructions he showed the workshop were 10 pages long. There was a great deal of white space throughout the document, which he said was good for readability. A nice feature of the medication section of the report, he noted, was that it listed both the brand name and generic name of all of the patient’s medications. Still, the medication instructions were formatted to fit into a thin column in the report and were inconsistent in terms of daily doses and the time of day that the doses should be taken. A more glaring deficit was the fact that the things that the patient had to do going forward, including information on new prescriptions and when to schedule follow-

up appointments, do not appear until six pages into this document. The seventh page contains instructions for health conditions that are completely unrelated to the patient’s health problems, and the information specific to the patient’s self-management needs does not appear until page nine of the discharge report.

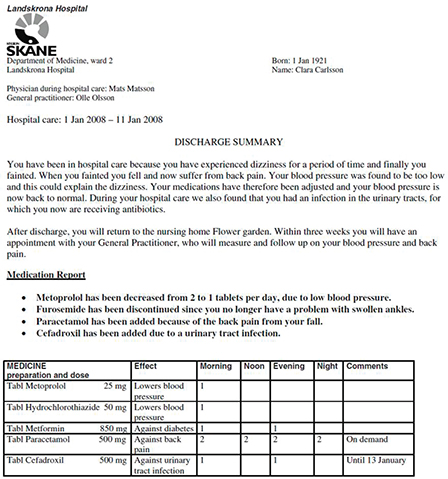

In contrast, a discharge instruction from Norway (see Figure 2-1), which was translated into English, provided some examples of useful features not found in the first example (Bergkvist et al., 2009). This report starts with a patient-friendly summary of why the patient had received care and a medication table that listed each drug’s dose, the reason why

FIGURE 2-1 Example of a discharge instruction sheet with useful features.

SOURCE: Bergkvist et al., 2009, as presented by Federman.

the patient needed to take the drugs, and how many pills the patient should take at specific times of day. “This is a much more low-literacy and patient-centric type of discharge summary,” said Federman.

Turning to an ambulatory visit summary, Federman noted that the meaningful use requirements dictate that such a summary be created after every visit and provided in either written or electronic format. The required elements for this summary include the patient’s name, clinical office contact information, the date and location of the current visit, an updated patient-specific problem list, a medication list, vital signs, and the reason for the visit, including symptoms. The report must also list all procedures, immunizations, and medications administered during the visit; all ordered tests and results if those results are available at the time of the visit; and a summary of topics covered, the time and location of the next appointment, the list of appointments that the patient needs to schedule with appropriate contact information, and recommended patient decision aids when appropriate.

Federman then presented the results of a study that he conducted in which he and a student did a convenience sampling of 18 primary care practices across the nation and used the Suitability Assessment of Materials (SAM) tool and Patient Education Materials Assessment Tool (PEMAT) to assess understandability and actionability of the ambulatory visit summaries. The summaries from the 18 practices were generated by seven different EHR platforms. The median font size was 10 points, which Federman characterized as fairly small, and the median length was two pages, with a range of one to seven pages. Every summary included patient-specific medication information, but only 78 percent of the summaries provided the primary care provider’s name, condition-specific instructions, or appointment information for procedures and consultations. Only two-thirds of the reports included the diagnosis, visit date, or vital signs; about one-half listed the patient’s allergies or information on return appointments; and only one-quarter of the summaries had a patient problem list or a generalized set of instructions such as what to do in case of emergency. The order in which this information was presented and how it was formatted varied greatly. “What that points to is that nobody is following a particular structure to building these after-visit summaries,” said Federman. “There is no common approach.”

In most cases, he added, the condition-specific instructions were typed in by the physician using free text. The text typed in by physicians was typically written with less medical jargon than text elsewhere in the documents. Overall, the median reading grade level on these materials was very high across four different reading grade formulas. The SAM tool scored readability as barely adequate, while the PEMAT assessment found that understandability was worse than actionability. Federman noted that the range of scores showed that some of the summaries performed very poorly.

He concluded his talk by presenting the results of phone interviews conducted with the physicians who participated in the study, which showed that clinicians judged medication lists as helpful but that most other elements were not. One of the major concerns that clinicians voiced was that these summaries should be available in Spanish.

LINK BETWEEN HEALTH LITERATE AFTER-VISIT SUMMARIES AND DISCHARGE INSTRUCTIONS AND IMPROVED OUTCOMES3

Darren DeWalt began the final presentation of the workshop’s first panel by commenting that providing discharge instructions is now a part of the workflow in health care thanks to the meaningful use requirements issued by the Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology but that there is still room for improvement. “This is a great opportunity to improve health care or to continue to create more waste,” he said. “What I mean by that is that if we are going through the motions or just checking boxes, we are just wasting our time. If we can turn this into a value for our patients and our consumers, then we could substantially improve health care.”

The reasons why it is difficult to “get this right,” as he put it, are many (Coleman et al., 2013; Makaryus and Friedman, 2005; Parkin et al., 1976). They include, on the patient side, the fact that difficulties arise because patients do not remember details, and they do not feel able to manage their lives and their medical issues because of low self-efficacy. Clinicians, meanwhile, do not understand the limits of their patients’ skills and abilities and as a result do not provide a manageable volume of clearly explained instructions and ensure that their patients understand the information they are given. In addition, information systems are not designed to produce discharge instructions in a low-literacy format, as Federman noted, and the content mandated by the meaningful use provisions may be overspecified, leading to the presentation of information that can complicate explanations rather than simplify them.

Health literacy, however, is not the only issue. Several studies have documented a range of between 30 and 43 percent of patients who have a cognitive impairment at the time of discharge that can impact their ability to comprehend or remember discharge instructions (Boustani et al., 2010; Coleman et al., 2013; Lindquist et al., 2011). Cognitive impairment resolves in 1 month in about half of these patients, but rates are even higher

_______________

3This section is based on the presentation by Darren DeWalt, associate professor of medicine, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, and the statements are not endorsed or verified by the IOM.

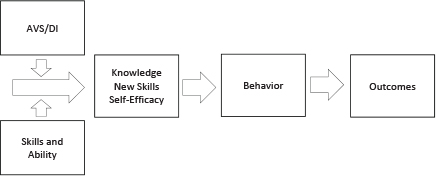

FIGURE 2-2 Mechanistic pathway by which discharge instructions impact outcomes.

NOTE: AVS/DI = after-visit summary/discharge instruction.

SOURCE: Presented by DeWalt, 2014.

in specific patient populations, such as elderly patients with heart failure, where the rate of cognitive impairment can exceed 50 percent.

The mechanistic pathway by which discharge instructions impact outcomes (see Figure 2-2) starts at the intersection of those instructions with the skills and abilities of the patient. Together, these two components have an effect on knowledge, new skills, and self-efficacy, which leads to behaviors that could produce better health outcomes. “Of course, if this is done poorly, it could lead to lower self-efficacy and worse behaviors and worse health outcomes,” said DeWalt.

To illustrate the challenges associated with this mechanistic pathway, DeWalt discussed the cases of two of his patients. One patient, a 60-year-old male admitted to the hospital with chest pain and shortness of breath, had had a heart attack and was hospitalized for 8 days. At the time of his discharge, he was left with substantial cognitive impairment, difficulty with mobility, and an overwhelmed spouse. He also left the hospital with nine pages of discharge instructions that DeWalt stated were “difficult to sort through with a very small font.” He added, “I can guarantee you that most of my patients are not referring to this information and that reading something like this is not particularly appealing for a medical patient that is still recovering from illness.” Given this patient’s status and the nature of the discharge instructions, DeWalt wondered whether the patient or family will make a mistake. He also questioned whether parts of this summary could be left out, and, if so, who should make that decision.

The second case he discussed was that of a 64-year-old female with high

blood pressure, rheumatoid arthritis, osteoporosis, and a recently ruptured hand tendon whom he had seen in his primary care office. At the time of her visit, her blood pressure was high, and DeWalt needed to increase her medication. She was also planning to have hip surgery soon. Given that she has several different medical problems and several different plans, DeWalt questioned whether she will remember what she needs to do if those plans are not integrated and written. He also wondered whether a medication list alone would have been sufficient at that moment in time and whether the problem list would help her in any way or whether it was just more information that would overwhelm her.

In today’s chronic care model, patient discharge instructions done well can be an important part of the productive interactions that can take place between an informed, activated patient and a prepared, proactive practice team and in the end produce good outcomes, DeWalt said. He argued, however, that poorly designed after-visit summary or discharge instructions have little impact on increasing or decreasing knowledge or skills but that they do decrease self-efficacy. “When we present something that is overwhelming, I think it gives patients more of the impression that they are not in control or can’t manage this. Consequently, I believe that these could have an adverse consequence of making it more difficult to carry out optimal behaviors,” he said.

In contrast, said DeWalt in closing, “I do believe that with good designs, we have an opportunity to improve knowledge skills and efficacy, and behavior and outcomes. I think that is the spirit with which policy makers have come into this, and I believe it is really our job as health systems and as activists, and at the roundtable, to try and help turn this into a win for our patients in our health system.” For him, doing so means giving up the idea that this is an information technology problem with an information technology solution. “We need to change how we think, and we need to change how we distill and present instructions,” he said. At his institution, the University of North Carolina, medical teams are asked to think about the three things that they want each patient to remember about their self-care and three things they need to do or look out for, and the fact is that most medical teams cannot do that. “We have some work to do in helping reframe how we think about handing this information off to our patients.”

Rima Rudd, senior lecturer on health literacy, education, and policy at the Harvard School of Public Health, started the ensuing discussion by asking whether it might be acceptable as a policy requirement to absolutely insist on a particular process for the development of these materials; the

process would involve rigorous pilot testing with members of the intended audience and evidence that change has been made based on that pilot testing. Seidman replied that there would be potential trade-offs associated with such a requirement. He said that although pilot testing can be very helpful—he is in fact in favor of increasing the amount of pilot testing done on discharge instructions—it can also slow down the process of developing discharge approaches that might work better. He also noted that such requirements could place a particularly large burden on organizations that have fewer resources to develop better discharge instructions.

In response to the same question, Federman thought that research and development involving focus groups, cognitive interviews, and other research methods could produce best practices for creating after-visit summaries in a way that achieves the goals intended for them. He also noted that one outcome of such research would be greater patient satisfaction, a point with which Seidman and DeWalt agreed. Both Federman and Seidman agreed with a comment from Kim Parson, director of the Consumer Experience Center of Excellence at Humana, who thought that bringing patients into the design phase for discharge summaries might produce a better product.

Patrick McGarry, vice president for new business innovation and connected health at the American Academy of Family Physicians, expressed concern that, during treatment, patients concede locus of control for care, trusting that their clinicians will make appropriate decisions. Yet on discharge, patients are expected to assume control of their own management. Federman responded that much of that shift in locus of control can be facilitated with greater use of personal health records, patient Web portals, and electronic communication, although we are still quite far from having adequate electronic interface with patients. Currently, therefore, hard copies of well-prepared and designed discharge and after-visit summaries are important tools. Seidman added, “There is still just a huge incentive for every clinician to bring every patient into the office in order to get paid. That is going to create a lot of problems around that locus of control.” DeWalt said that he believes that “after-visit summaries and discharge instructions, when done right, provide an opportunity to improve the patient’s efficacy around their own self-management.”

Cindy Brach, senior health policy researcher with the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality and a roundtable member, asked the panelists if they had any suggestions on how to speed the development of better discharge instructions. Seidman thought that the readmission penalties that Medicare is now levying are already motivating hospitals to think through their discharge instructions. “Now you have thousands of hospitals thinking how to improve their discharge instructions because they have to reduce their readmissions. I think that has created a lot of incentive and a

lot of positive work,” he stated. He also thought that the National Quality Strategy4 was a great tool for pushing the development of better discharge instructions. Federman thought that “another driver could be the next iteration of meaningful use criteria if they were to say that the after-visit summary has to have demonstrated impact or has to meet some formatting or other characteristics that makes it health literate.”

Winston Wong, medical director for Kaiser Permanente’s Community Benefit Disparities Improvement and Quality Initiatives program, said that giving health-literate instructions is critical but that it is also critical to provide support for a patient’s transition back home. He then asked if any of the panelists had experience in making discharge instructions more understandable to non-English-speaking patients. Federman, who noted that his clinical practice is in East Harlem, which has a large population of patients who speak only Spanish, said that regulations are needed to address this problem. He said that health care systems want to do something about this because it certainly impacts readmission rates, but their list of things they need to do is so long that addressing language issues becomes less of a priority.

Robert Logan, communication research scientist at the National Library of Medicine, asked what the speakers thought were the challenges of selecting the appropriate information to provide. Seidman said that, from his experience, patients want in-depth information, but they want it to be specific to their situation. The problem is creating systems that can do that. Federman added that when the situation is more complex, we have to bring in tools other than the summaries we are discussing. “In some cases people need navigators, or they need care coaches or other things,” he said. Finding the right balance of components is part of the puzzle we are trying to figure out.

Kim Parson pointed out the importance of the principle of co-design of materials. Is the consumer being involved in the creation of discharge and after-visit summaries, she asked? Federman responded that he and his colleagues have a grant to do just that. Seidman pointed out that although co-design is very important, it can present challenges. For example, the

_______________

4The National Quality Strategy, led by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, has three aims:

- “Better Care: Improve the overall quality, by making health care more patient-centered, reliable, accessible, and safe.

- Healthy People/Healthy Communities: Improve the health of the U.S. population by supporting proven interventions to address behavioral, social, and environmental determinants of health in addition to delivering higher-quality care.

- Affordable Care: Reduce the cost of quality health care for individuals, families, employers, and government”

http://www.ahrq.gov/workingforquality/about.htm#aims (accessed July 17, 2014).

physician is probably not the best-trained person to do this. Second, from a resource perspective, using co-design can be very time-consuming. A team approach to care might be more able to accomplish this, he said. DeWalt pointed out that in his organization there are separate discharge instructions from physicians, from the nursing team, from the pharmacy team, and from others as well, which “muddies the water even further.” There needs to be a way to consolidate these instructions, he said.

Bernard Rosof, co-chairman of the National Priorities Partnership of the National Quality Forum and a roundtable member, asked what drivers should be emphasized as we create health-literate discharge and after-visit summaries. For example, should we think about the National Quality Strategy drivers of patient safety, patient-centered care, care coordination, and decreasing the leading causes of mortality? Seidman responded that the National Quality Strategy priorities could bring focus and guidance to efforts to create health-literate discharge and after-visit summaries.

Margaret Loveland, from Global Medical Affairs of Merck & Co., Inc., said that perhaps as discharge instructions are designed, the most important things should be placed first, things such as in the first two days at home you will do X. She also pointed out that the predischarge process is important, as is postdischarge follow-up. Seidman agreed that the predischarge process and postdischarge follow-up are critical, referring to the work of Eric Coleman on the care transitions model (http://www.caretransitions.org/overview.asp), adding that the ability to engage family caregivers is very important. He said that another critical piece is the dosing of information. “We have got to make sure that we get the right dose, the right frequency, the right duration. All of those things are very similar to medication prescribing,” he said.

DeWalt agreed and pointed out that “discharge instructions, in and of themselves, are not going to solve the problem.” He pointed out that the current state of discharge instructions reflects a generally disorganized plan put in place for the patients. “Working on how we organize and present the discharge instructions will help the team as they prepare the patient in the predischarge and postdischarge arena,” he said.

Laurie Francis, senior director of Clinic Operations and Quality at the Oregon Primary Care Association and a roundtable member, asked how we can move from a focus on physician communication to one that concentrates on patient priorities and uses the care team to provide better care. Federman said, “Payment models.” He pointed out that there are many ongoing demonstrations and research studies about engaging community health workers as members of the health care team. It is not enough to tell patients what is needed at the point of discharge or even 1 week after discharge; patients also need to be checked on over time to reinforce what needs to be done, he said.