3

Inpatient Discharge Summaries

The workshop’s second panel was structured with one presentation and three reactions to that presentation. In the main presentation, Mark Williams, director of the Center for Health Services Research and professor of internal medicine at the University of Kentucky, described elements that should be included in an inpatient’s discharge instruction and the formatting techniques that can improve readability for patients. Benard Dreyer, professor of pediatrics at the New York University School of Medicine; Avniel Shetreat-Klein, assistant professor and associate medical information officer for Epic Operations at Mount Sinai Medical Center; and Man Wai Ng, chief of the Department of Dentistry at Boston Children’s Hospital and assistant professor of developmental biology at the Harvard School of Dental Medicine, gave their reactions to that presentation.

KEY ELEMENTS AND FORMATTING DISCHARGE INSTRUCTIONS1

One recent revision to CMS’s Conditions of Participation that health care organizations must meet to participate in Medicare and Medicaid programs was the provision that all hospitals must have, in writing, a discharge planning process that applies to all patients. This requirement, said Mark Williams, is expected to improve the quality of care and reduce the chances

_______________

1This section is based on the presentation by Mark Williams, director of the Center for Health Services Research and professor of internal medicine, University of Kentucky, and the statements are not endorsed or verified by the IOM.

of readmission by creating incentives to provide patients what they need for a smooth and safe transition out of the hospital. The discharge process, according to Medicare’s guidelines, should consist of four parts: screening for the risk of adverse health consequences after discharge; evaluation of a patient’s postdischarge needs; development of a discharge plan; and initiation of the discharge plan prior to the patient’s actual discharge.

Williams noted that any case manager, if asked, will say that hospital discharge planning should begin with hospital admission, but that often does not happen. The Medicare guidelines say that the discharge planning process should include input from medical staff, postacute care facilities, patients, and advocacy groups, but Williams wondered how many hospitals actually integrate all of these inputs into discharge planning. In fact, he said, information and communication deficits at hospital discharge are common, according to the findings of a study he and his colleagues conducted in 2006 (Kripalani et al., 2007). This systematic review found that there was little direct communication between the hospital provider and the community-based care team and that discharge summaries were not commonly available at postdischarge appointments. Even when the summaries are available, the majority lack important information, such as diagnostic test results, a list of tests with pending results, and discharge medications (Were et al., 2009).

In 2009, Williams and a number of colleagues representing several medical societies published a consensus policy statement regarding transitions of care (Snow et al., 2009). One omission from the process that generated this consensus statement, he said, was that patient groups were not involved in creating this consensus statement; nonetheless, he said, it contained a number of principles that are still important and that should drive much of what hospitals do when trying to communicate with patients. These principles include the idea that hospitals should be accountable for what is happening to patients as they transition through the system, taking responsibility to ensure that patients and their families know who is in charge of the patients’ care and how to contact that caregiver throughout the process of hospitalization, discharge, and postacute care. Another principle is that there must be coordination of care and family involvement, along with an infrastructure that provides clear and direct communication, including transition records, treatment plans, and follow-up expectations. Finally, Williams said, is the principle that all communication and feedback should be timely and meet national standards and metrics as established by The Joint Commission and the National Quality Forum.

CMS has issued a discharge planning checklist for patients to receive and use prior to hospitalization, and although it is a useful summary of what a patient should expect at discharge, Williams said that it places too much burden on the patient to figure out what should happen instead of

being part of a collaborative process among health care providers, patients, and caregivers. He noted that in many years caring for patients and working in many hospitals, he has seen or heard of few cases where patients actually have and used such a checklist. “We certainly don’t typically help patients do something like this,” said Williams. Nonetheless, he noted that his institution has its own checklist that it provides patients on admission and that there are similar items available from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). Such checklists provide an opportunity for the education of patients and caregivers using a teach-back approach2 and could inform what hospitals ought to be doing.

One recent study that Williams participated in looked at what patients actually understand and can execute when they return home (Coleman et al., 2013). Results of interviews with patients after they had gone home showed that health literacy, cognition, and self-efficacy predict successful understanding and execution of discharge instructions. Nevertheless, neither the discharge diagnosis nor the complexity of the instructions was a predictor of success. Williams said that on the basis of these findings, “there needs to be a reliable protocol that identifies patients at high risk for poor understanding and execution of the discharge instructions, and we need to have customized approaches for those patients.”

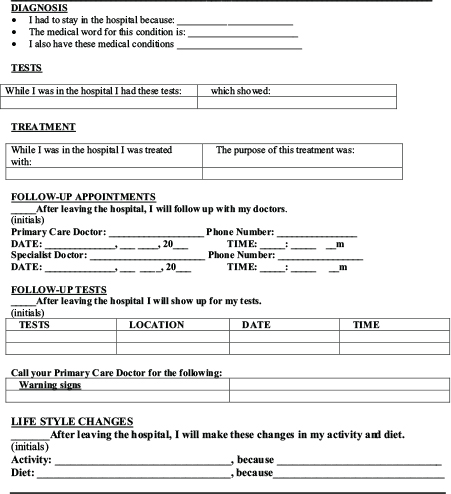

As part of a project funded by AHRQ to develop an effective and easy-to-understand set of discharge instructions, Williams worked with patients to develop what is now called the Discharge Patient Education Tool. This tool is laid out in a structured manner and takes a patient-centered approach to explaining discharge instructions (see Figure 3-1). It explains why the patient was in the hospital and encourages health care providers to explain, in “living room language,” definitions of any medical terminology as well as the medical terms. It lists the patient’s medical conditions, the tests that were run and their results, the treatments the patient received and the purpose of those treatments, and follow-up information, including appointments and necessary lifestyle changes. All this information fits on two pages, though Williams and his colleagues as part of Project BOOST (Better Outcomes by Optimizing Safe Transitions, www.hospitalmedicine.org/BOOST) developed an even more concise discharge instruction template that hospitals might choose to use.

The fascinating part of this project, said Williams, was that when nurses used these structured patient-centered discharge instructions, the patients reacted very strongly and positively. “A common comment was, ‘Why haven’t they done this in the past when I was discharged from the hospital,’” said Williams. Still, 7 years later, these simplified forms have

_______________

2Teach-back is a method for making sure patients understand what they need to know by asking them to explain back to the provider in their own words.

FIGURE 3-1 Discharge Patient Education Tool.

SOURCE: BOOST, presented by Williams, 2014.

yet to be integrated into an electronic record despite working with an EHR vendor. In closing, he noted the perversity of this situation given that EHRs can easily generate 30 pages of instructions with no formatting. “While you can come up with something simple and straightforward on your personal computer, we are now obligated to use the EHR, and so we have got to figure out how to get this integrated into EHRs as a standard part of hospital transitional care,” Williams said.

When asked by Andrew Pleasant why integration into any vendors’ EHR has been so challenging, Williams said that he has been told that it will take 2 to 3 years of reprogramming to finally get this capability implemented, that is, the capability to have infinitely expandable tables and pulling of needed information seamlessly into the patient discharge instructions. “It is impressive how the EHR companies are now controlling so much of what is happening in hospitals as they attempt to meet meaningful use criteria,” Williams said.

The first issue that Benard Dreyer addressed was information overload, and he proposed several steps to deal with the potential of overwhelming patients with too much information. Clinicians, he said, should think about the most important actions that the patient needs to take and how those actions might differ from the patient’s usual behaviors, especially the health-related activities of the patient prior to this admission. This type of information can be lost in the typical discharge instructions. He suggested that a teach-back moment should take place to ensure that the patient truly understands the discharge instructions and that a telephone call should be made to the patient after discharge as an additional check on the patient’s understanding. Patients should also be given specific instructions on when and how they should contact their physician after discharge. Regarding the checklists that Williams described, which could incorporate these items as questions that the patient should ask, Dreyer thought they could be useful but wondered whether they should be given to patients during their admission process rather than ahead of time, when they will likely be forgotten.

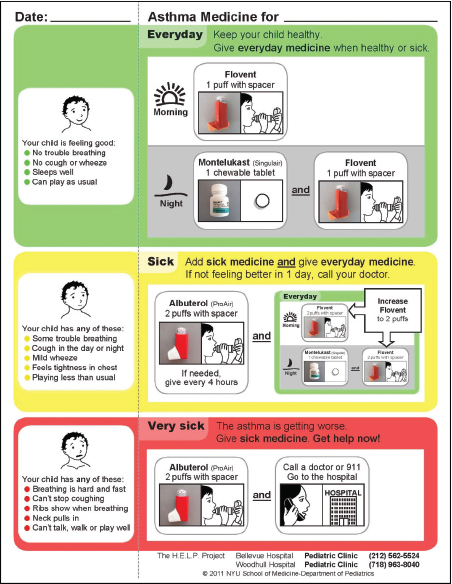

Dreyer briefly discussed a few tools that patients could take home. He and his colleagues use simplified written asthma action plans and medication administration and medication-taking tools. He described a low-literacy asthma action plan (see Figure 3-2) that uses illustrations and pictures of medications, along with color-coding and formatting, to convey information in as simple a format as possible. Dreyer also remarked that smartphones, videos, and Web-accessible programs can be valuable tools for communicating with patients. For example, New York University Medical Center has developed a Web-accessible program that providers can access

_______________

3This section is based on the presentation by Benard Dreyer, professor of pediatrics at New York University School of Medicine, and the statements are not endorsed or verified by the IOM.

FIGURE 3-2 Asthma medication plan.

SOURCE: NYU School of Medicine, 2011, as presented by Dreyer.

to generate interactive patient-specific asthma action plans with embedded video instructions on how the parent and/or child should use an inhaler.

Dealing with unfinished business at the time of discharge can be challenging, said Dreyer. Unfinished business can include laboratory test results that are not back yet at the time of discharge and a list of treatments that need to be arranged after discharge. He noted, too, that patients with certain diseases want to know how their disease will affect them going forward. “We as physicians tend to focus on the short run, but patients want to know what is really going to happen to them in the long run.” They also want to know how long it will take for them to return to their normal activities, such as school and work.

In the end, all these concerns come down to one ultimate question, said Dreyer. “How much of this is our responsibility? If we decide something is not our responsibility, then who is going to be doing that for the patient?” he asked. Things often fall apart, he noted, when patients go home and some important detail was not addressed either by the hospital or by resources in the community. Often, these are simple pieces of information, such as where the pharmacy is located and what its hours of operations are and whether the patients have the money to take care of the drug co-pay. “I often find that the small things that are overlooked cause serious problems when the patient goes home,” said Dreyer, who concluded his comments by noting that the field needs to figure out the easiest ways for patients to get those details once they leave the hospital. He stressed that we need to make sure the patient is ready and prepared for care after discharge, the family and home environment is ready for the patient, and the community and the health care system have the resources and responsibilities necessary for a successful transition.

Avniel Shetreat-Klein commented on the difficulty in getting EHRs to produce simplified, readable discharge instructions. Informatics aims to deliver the right information to the right person at the right time. It is doing a good job of giving information for clinical decision support to providers who are working to care for patients. But, Shetreat-Klein said, it is not doing such a great job in terms of the interaction between the EHR and the patient. “Automation—the desire to get the EHR to solve these problems—is to a huge degree what causes these problems,” he said. When something is automated, one has as much chance of including bad infor-

_______________

4This section is based on the presentation by Avniel Shetreat-Klein, assistant professor and associate medical information officer for Epic Operations, Mount Sinai Medical Center, and the statements are not endorsed or verified by the IOM.

mation as including good information. Automated after-visit summaries include medication lists, problem lists, and patient education information that are pulled in automatically from the medical record. As a result, there are errors. For example, one automated after-visit summary included insulin on the medication list four separate times. Presumably that was because the patient was on a sliding scale in the hospital, so there were four different insulin orders—which is its own problem, he said.

Shetreat-Klein noted that the desire to automate, combined with the desire to add in all the information that guidelines recommend, including in discharge instructions, produces exactly the kind of dense, multipage discharge instructions that previous speakers discussed. What needs to change, he said, is not the information that goes into the discharge instructions or the software that organizes that information into a readable form, but the discharge process itself. In fact, Shetreat-Klein argued against trying to integrate discharge instructions into the EHR. Yes, he said, create a one- or two-page form, but keep the physician involved in filling in the patient-specific blanks on that form.

“It is the process of thinking ‘what does this patient need?’ that provides beneficial information, rather than the garbage-in, garbage-out kind of discharge summary,” he said. Williams’s example of the BOOST discharge form is great, partly because, he said, “it is not part of the EHR.” It changes the process; providers must actually write on the form, which requires a process of thinking about what the specific patient needs.

Although patient checklists can be useful, Shetreat-Klein said, a matching physician checklist should be created in the EHR that would prompt the physician to address all the relevant issues germane to a specific patient. Alternatively, the patient could go over the checklist in the presence of the health care provider, which Shetreat-Klein suspected might make a difference in patient understanding and follow-through. “Removing the automation from the process may help,” he said.

Man Wai Ng provided some context for her remarks. She is a pediatric dentist working in a hospital department of dentistry that sees about 28,000 ambulatory patient visits each year. About 750 patients each year receive their dental treatment in the operating room under general anesthesia. The dental service also provides coverage to the emergency department and consultations to patients prior to such treatments as chemotherapy, stem cell transplant, and open heart surgery. Until recently, Ng said, den-

_______________

5This section is based on the presentation by Man Wai Ng, Harvard School of Dental Medicine, and the statements are not endorsed or verified by the IOM.

tistry has been thought of as a profession that treats cavities (tooth decay) and gum disease. More recently, however, dental caries (or tooth decay) has come to be recognized as a chronic infectious disease that can be prevented and managed. As a result, her hospital has implemented a risk-based disease prevention and management of caries approach that builds on the chronic care treatment model, in collaboration with patients and families, and implementing self-management goals handouts, using pictograms and examining the language used to communicate with patients. Ng noted that electronic dental records are “woefully misaligned” with EHRs. She and her colleagues are challenged to easily provide the educational information that is relevant to patients’ oral health concerns and that the patients and their family can access through the hospital’s patient portal. The portal is managed as part of the EHR. She also remarked that she believes three processes need to be considered prior to initiating the discharge process for one of her pediatric cases. “One is the need to specify those goals for discharge, two is to assess the child’s health care needs, and then three is to identify factors that would influence the child’s health upon discharge,” Ng explained. The purpose of these three processes, she added, is to screen and identify individual patients for whom a lack of an adequate discharge plan will likely result in unnecessary delay from discharge or impact health after discharge.

The discharge process, she continued, should ideally begin when the child arrives at the hospital, and it should involve all members of the care team. The discharge plan should include teach-back, and it should be delivered with consideration of the parents’ English-speaking skills. Ng commented that although online access to discharge instructions and other patient-relevant issues can play an important role in the discharge process, not all patients will have easy access to the Internet. “There needs to be some recognition of this digital divide,” she said.

During the subsequent discussion, Cindy Brach suggested it was important to distinguish between a discharge summary and a discharge plan or instructions. She also said that she thinks the focus should be on consumer-facing instructions and believes that this should be integrated into the EHR, unlike Shetreat-Klein, even if doing so takes time. Williams agreed that integration into the EHR is critical. Also important are other support tools. The system is not adequately providing information to patients in an understandable manner and supporting their connection to resources after discharge, he said. Tools such as navigators are important to the discharge and postdischarge process.

Shetreat-Klein clarified that his concern about keeping discharge sum-

maries out of the EHR is that once one starts automating the system, instead of having interaction between the provider and the patient about his or her specific problem using common words, one gets a form with all the problems discussed earlier, such as medical jargon, information error, and nonspecific information.

Winston Wong highlighted the importance of patient-centeredness and emphasized the importance of teach-back as a tool to ensure that patients and caregivers understand discharge instructions, and it was noted that teach-back is now becoming widely used across the country. Williams noted that teach-back appears to improve patient satisfaction to a degree that gets reflected on patient satisfaction surveys used by CMS for hospital and physician reimbursement. He added that teach-back needs to be used by all members of the health care team, not just by the last person who sees a patient before discharge. He also noted that combining teach-back with an instrument such as the discharge patient education tool leads to high marks on patient satisfaction. “The patients actually felt that they were receiving attention and [that] the provider cared about them because they were delivering the information in an understandable fashion,” he said. Williams said that he is fascinated by what patients tell him. “If I don’t know what they are thinking,” he said, “then a lot of my conversation is wasted because I have not addressed their concerns up front.”

Ng said that when they were thinking about bringing in technology to help patients understand different components around discharge, they asked patient representatives what they thought. The feedback was that technology is great but what they really would rather have are the interactions patients and families have with the care providers. Dreyer then said that he believes that pilot testing is a critical part of developing patient discharge instructions that get at the issues of what patients need and want to know. Rima Rudd noted that pilot testing is not something that should be done on a casual basis. “It is part of the absolute scientific rigor of formative evaluation,” she said, “and to the extent that people make excuses, that is totally unscientific and ethically irresponsible.”

Terri Ann Parnell, vice president for health literacy and patient education at North Shore–Long Island Jewish Health System and a roundtable member, asked for the presenters’ thoughts on the use of texting and audio and video presentations as mechanisms for providing discharge information. And Linda Harris, from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and a roundtable member, wondered whether patients, even those with smartphones, have enough bandwidth and data to have meaningful access to health information, which involves the question of who pays. Dreyer said that he did not have any information about the value of audio and video for providing discharge information. As far as the use of texting, Dreyer said that numerous research projects are examining the use of

texting for connecting to patients. Nevertheless, in his opinion, providing adequate discharge instructions requires more than texting. And the issue of who pays is key. Wilma Alvarado-Little suggested that one might consult the deaf community about the use of texting because that is a major communication tool for that community.

Bernard Rosof said he perceives a problem in providing discharge information that is related to the way in which medical care is delivered. Over the past 5 to 10 years, he said, the primary care physician (PCP) presence in hospitals has declined significantly. Patients are given their discharge summaries, but those summaries are not forwarded to the PCP. If, after discharge, something happens that requires primary care intervention, the PCP does not have information about what happened in the hospital or post discharge. Rosof asked how we can ensure that a timely transfer of information to the PCP occurs.

Williams said that this is a critical issue because PCPs need to know if their patients come to the emergency room or are admitted to the hospital; they need to communicate with the hospitalists and, ideally, have access to and be able to react to the electronic medical record. PCPs also need to know when the patient is leaving the hospital and arrange for a follow-up appointment. Lindquist and colleagues (2013) conducted a study that found PCP communication at hospital discharge reduces medication discrepancies.

Shetreat-Klein agreed that the primary care provider is central to the entire process. While we have gotten very good at identifying who patients need to follow up with after discharge, alerting the primary care provider to a hospital admission is something that requires individuals to act on their own to see that it is done, he said. Another major challenge is that sometimes patients do not have a primary care provider or do not know who their PCP is. This situation occurs particularly in the more vulnerable populations, who may be getting care at a clinic where their provider is a resident who changes over time.

Steven Rush suggested that perhaps one might think about discharge preparation rather than focus on discharge instructions, teaching patients while in the hospital how to care for themselves. For example, he said, patients could be taught how to take their medications and what kinds of physical activities in which they could engage. Williams responded that he thinks we should be focusing on patient preparation, but because there is pressure to get patients out of the hospital as rapidly as possible, the system has not be set up to do this kind of training.

As the discussion concluded, Darren DeWalt asked the panelists to provide their recommendations for future actions. Williams said that hospitals need to engage industrial engineers to support the development of better discharge instructions and to integrate electronic medical records into the workflow of the care providers to best serve the patients. Dreyer said that

the field needs to conduct research on patients’ understanding of discharge instructions as they are now designed and that it may be necessary to mandate via regulation that hospitals conduct pilot testing. Shetreat-Klein agreed with both of these ideas and added that health care providers need to be brought back into actively designing the discharge process. Ng said that it was critical to think about discharge instructions in terms of systems and that all stakeholders need to be involved in the planning process, with subsequent testing prior to implementation.