3

Air Force Use of the C-123 Provider: Background and Sampling Data

The Fairchild C-123 Provider is a short-range military assault aircraft used by the Air Force (AF) in Vietnam. Designed by the Chase Aircraft Company in New Jersey and built by Fairchild Industries in Hagerstown, Maryland, the C-123 was utilized in Vietnam for a range of tactical missions including transportation of military personnel and equipment, evacuation of wounded soldiers, and supply operations for advanced combat positions. This chapter provides background information about the use of C-123 Provider aircraft to spray herbicides in Vietnam and their subsequent use by the AF Reserve personnel in the United States. Descriptions of air and wipe samples collected from some of these aircraft between 1979 and 2009 by the US Air Force (USAF) are also presented.

USE OF C-123S IN VIETNAM

During the military conflict in Vietnam, one use of Fairchild UC-123 aircraft was flying defoliation missions to destroy enemy food supplies and to clear and expose enemy transportation and infiltration routes (IOM, 1994; Young, 2009; Young and Newton, 2004). “UC” was a designation given to C-123 aircraft that were equipped with spray apparatus. The UC-123s were estimated to have sprayed 88% of all herbicides used in Vietnam (AF Working Paper, 1979). Herbicide formulations used in defoliation efforts were composed of four compounds—2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid (2,4-D), 2,4,5-trichlorophenoxyacetic acid (2,4,5-T), 4-amino-3,5,6-trichloropicolinic acid (picloram), and dimethylarsinic acid (cacodylic acid). An estimated 69 to 77 million liters of herbicides were sprayed over roughly 3.6 million acres in Vietnam between 1961 and 1971 (NRC, 1974; Stellman et al., 2003). The specific herbicide formulations (named for the band of color around each

55-gallon storage drum—Agents Pink, Green, Purple, Orange, White, and Blue), chemical composition, TCDD concentration, year used, and quantity sprayed are shown in Table 3-1.

Operation Ranch Hand

Historically, the approximately 1,300 AF personnel involved in the UC-123 fixed-wing aircraft spray activities in Vietnam between 1962 and 1971 (codenamed

TABLE 3-1 Military Use of Herbicides in Vietnam (1961–1971)

| Code Name | Chemical Constituentsa | |||

| Formulations with TCDD Contamination | ||||

| Pink | 60% n-butyl ester, 40% isobutyl ester of 2,4,5-T |

|||

| Green | n-butyl ester of 2,4,5-T | |||

| Purple | 50% n-butyl ester of 2,4-D, 30% n-butyl ester of 2,4,5-T, 20% isobutyl ester of 2,4,5-T |

|||

| Orange | 50% n-butyl ester of 2,4-D, 50% n-butyl ester of 2,4,5-T |

|||

| Orange II | 50% n-butyl ester of 2,4-D, 50% isooctyl ester of 2,4,5-T |

|||

| Formulations Without TCDD Contamination | ||||

| White | Acid weight basis: 21.2% triisopropanolamine salts of 2,4-D, 5.7% picloram | |||

| Blue powder | Cacodylic acid (dimethylarsinic acid) sodium cacodylate | |||

| Blue Aqueous solution | 21% sodium cacodylate + cacodylic acid to yield at least 26% total acid equivalent by weight | |||

| Total, all formulations | — | |||

NOTES: 2,4-D, 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid; 2,4,5-T, 2,4,5-trichlorophenoxyacetic acid; gal, gallon; L, liter; ppm, parts per million; TCDD, 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin; VAO, Veterans and Agent Orange: Update 2012 (IOM, 2014).

Operation Ranch Hand [ORH]) have been considered among the most highly exposed workers to the chemicals that were in the defoliants. Defoliation spray missions were carried out by highly-trained three-person crews of male Ranch Hand (RH) personnel consisting of a pilot, copilot/navigator, and a spray equipment console operator. Personnel who provided primary maintenance for the ORH UC-123s

| Amount Sprayed | ||||

| TCDD Concentration | Years Useda | VAO Estimateb | Revised Estimatea | |

| 65.6 ppm | 1961, 1965 | 464,817 L (122,792 gal) | 50,312 L sprayed; 413,852 L more on procurement records | |

| 65.6 ppm | 1961, 1965 | 31,071 L (8,208 gal) | 31,026 L on procurement records | |

| Up to 45 ppm | 1962–1965 | 548,883 L (145,000 gal) | 1,892,733 L | |

| 0.05–50 ppm (average, 1.98–2.99 ppm) | 1965–1970 | 42,629,013 L (11,261,429 gal) | 45,677,937 L (could include | |

| 0.05–50 ppm (average, 1.98–2.99 ppm) | After 1968 | — | Agent Orange II) Unknown; at least 3,591,000 L shipped | |

| None | 1966–1971 | 19,860,108 L (5,246,502 gal) | 20,556,525 L | |

| None | 1962–1964 | — | 25,650 L | |

| None | 1964–1971 | 4,255,952 L (1,124,307 gal) | 4,715,731 L | |

| — | 67,789,844 L (17,908,238 gal) | 76,954,766 L (including procured) | ||

a Based on Stellman et al., 2003.

b Based on data from MRI, 1967; NRC, 1974; Young and Reggiani, 1988.

SOURCES: Adapted from IOM, 2009, 2011.

were also potentially exposed to herbicides (AF Working Paper, 1979). Lurker et al. (2014) reported that the aircraft flew a total of almost 6,000 herbicide missions and became heavily contaminated with chemical residues during loading, maintenance, fueling, and while on missions. ORH crews had the potential for exposure when flying with the cockpit windows or rear cargo door open, flying through previously sprayed airspace, or by exposure to broken or malfunctioning spray lines or spillage from storage tanks. The extent of exposure of ORH ground crews or C-123 flight personnel in Vietnam has not been documented, but estimates of exposure based on days of exposure, percentage of skin exposed, the concentration of herbicide formulations, and serum TCDD concentrations, show that this population had the potential for even higher exposures than flight crews (Michalek et al., 1995).

USE OF C-123S AFTER THE VIETNAM CONFLICT

In 1970, the herbicide 2,4,5-T, which was included in the chemical formulations for Agent Orange (AO) (or Herbicide Orange), Agent Green, Agent Pink, and Agent Purple, was found to be contaminated with a byproduct of manufacturing, 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (TCDD) or dioxin. Shortly thereafter, AO ORH missions were terminated after toxicologic studies found that TCDD caused congenital abnormalities in pregnant rodents (Courtney et al., 1970; Lindquist and Ullberg, 1971; Robinson et al., 2006). In late 1971, the White House issued an Executive Order, calling for the phasing out of all herbicide spray activities in Vietnam (AF Working Paper, 1979; Cecil, 1986). TCDD concentrations in AO samples taken after the Vietnam conflict varied from 0.05 parts per million (ppm) to nearly 66 ppm, with an average of 2–3 ppm (NRC, 1974, Young et al., 1978). At that time in the United States, TCDD contamination of 2,4,5-T could not exceed 0.5 ppm (NRC, 1974).

Between April 1969 and February 1972, 30–40 UC-123 aircraft used for ORH returned to the continental United States. Table B-1 in Appendix B lists these aircraft, as well as information on other ORH C-123s that did not return from Vietnam, compiled from Carter (2013), Alvin L. Young (personal communication, May 5, 2014), Young (2014), and Young and Young (2014a,b). Young and Young (2012, 2014a) report that of the former ORH aircraft, approximately 24 were distributed among AF Reserve units in the United States and thirteen were transferred to the Military Assistance Program (MAP), a program designed to sell aircraft to other nations for their military and domestic use.

All C-123s returning to the United States from Vietnam passed through the Military Aircraft Storage and Disposal Center (MASDC), which adjoins the Davis-Monthan Air Force Base (AFB) in Tucson, Arizona (Young and Young, 2014a,b). The MASDC facility operated as an aircraft storage, preservation, and maintenance facility for all the US Armed Forces. Typically aircraft arriving at this facility were reconditioned and returned to service; however, unsalvage-

able aircraft could be used for spare parts or target practice, transferred to other locations for museum displays, or smelted down into metal ingots and recycled (AMARG, 2014). Aircraft that arrived at this facility from Vietnam were stored for 3–6 months, during which time the spray tanks and booms were removed from the aircraft (Young and Young, 2014b).

Once spray equipment was removed from serviceable ORH aircraft, the C-123s were ferried to the Hayes Aircraft Facility at Napier Field, in Dothan, Alabama, to undergo reconditioning. The reconditioning process took between 3–6 months. Descriptions of the C-123 reconditioning process included cockpit standardization and engine repair; removal and replacement of all armor, seats, damaged flooring, and fuselage; instillation of new oxygen systems; industrial vacuuming; and internal and external cleaning and painting as appropriate for future use (Alvin L. Young, A.L. Young Consulting, Inc., personal communication, May 5, 2014; Young, 2014).

Written testimony provided by the C-123 Veterans Association to the committee, however, reported that the aircraft returning from Vietnam received only basic maintenance at a repair depot and needed extensive rehabilitation by maintenance personnel. The AF Reserve personnel reported that some C-123 aircraft arrived needing seats replaced, new litter stanchions, litter straps, first aid kits, matting, and in some aircraft, navigator stations. The exterior of some aircraft were patched but not repainted. The veteran’s account stated that the AF Reserve crews worked to remove residue from the interior of the C-123 aircraft and exterior washing was undertaken with soap solutions applied with brushes and pressurized spray equipment (Carter, 2014a).

The efficacy of the reconditioning process or the AF Reservists’ efforts in removing remnants of herbicides sprayed in ORH is at odds with the existing results from samples drawn many years later, which are the focus of this report.

Assignment of C-123s to AF Reserve Units

Once cleared from Napier Field, C-123 aircraft formerly used for ORH were assigned to AF Reserve units or sold overseas. The C-123s that remained in the United States were transferred to the 906th or 907th Tactical Airlift Groups (TAGs) located at the Lockbourne/Rickenbacker AFB in OH, the 911th TAG located at Pittsburgh International Airport in Pennsylvania, or the 731st Tactical Airlift Squadron (TAS) at Westover AFB in Massachusetts. The C-123s transferred to TAGs or TASs were used between 1972 and 1982 by AF Reserve personnel for military airlifts, medical transport, and cargo transport in the United States and internationally. Thirteen former ORH C-123s were sold through the Military Assistance Program to other countries, including El Salvador, Korea, Laos, the Philippines, South Vietnam, and Thailand (detailed information is included in Table B-1 in Appendix B).

AF Reserve Work Practices on Repurposed C-123s

Between 1972 and 1982, approximately 1,500–2,100 AF Reservists worked aboard C-123 aircraft that had previously been used to spray herbicides in Vietnam. It has been estimated that approximately one-third of all the C-123 aircraft used by the AF Reservists were former ORH planes (Alvin L. Young, A.L. Young Consulting, Inc., personal communication, August 10, 2014). The AF Reserve crews were assigned to different aircraft for each mission so it is likely that they spent time in ORH C-123s sometime during their service (Carter, 2014b). The committee notes that even if the ORH C-123s constituted less than one-third of a unit’s fleet, with random assignment of planes for each mission, the probability of never serving on an ORH C-123 after a dozen or so missions is 0.013. Traditional AF Reservists worked one weekend per month plus one 2-week training session annually. Some maintenance and flight crews worked 5–10 days per month and other maintenance and flight crews worked full-time, either as Reservists or as Air Reserve Technicians (Carter, 2014a). Each C-123 flight crew included a pilot, navigator, flight engineer, and a loadmaster. In addition to the flight crew, maintenance personnel, paratroopers, and aero-medical personnel (including nurses), all had duties which could have brought them in contact with former ORH C-123s (Alvin L. Young, A.L. Young Consulting, Inc., personal communication, May 5, 2014).

The length of time the AF Reserve crew members spent aboard C-123s (both in flight and on the ground) could vary from 4.5 to 12 hours per shift depending on the mission or circumstances (Carter, 2014b). Typical pilot training and aeromedical evacuation missions were 4 hours in length; missions involving transport of weapons, explosives, or vehicles could be much longer. Cross country training missions were typically 4–7 hours to reach a specific destination away from home base. Deployments to Europe or South America lasting up to 12 hours in length were conducted with extended range fuel tanks (Carter, 2014b).

According to former AF Reservists, a flight mechanic would complete a 1.5-hour preflight inspection prior to each mission. Loadmasters required approximately 1.5 hours to prepare for aeromedical evacuations or missions involving an air drop of cargo or personnel. Static ground training missions held on the tarmac required crews to remain in C-123s for long periods of time. These immobile training sessions, during which crew members would rotate through different crew positions for training purposes, could last as long as a regular inflight mission. For medical missions, aircrew would test medical systems, place litter straps and stanchions in place, and load, test, and store equipment. Medical personnel had contact with the floor while working along gurneys that were close to the floor. During training missions, the AF Reservists simulated patients who were loaded and “treated” in flight. During routine flight operations, flight crews sat on the floor, reclined, kneeled, sat on bucket seats, or crawled while completing their duties or doing maintenance work. Crew members routinely touched

the deck, top, and sides of the aircraft interior. Maintenance personnel were even more intensely in contact with the aircraft interior surfaces (Carter, 2014a). Maintenance workers were tasked with painting, sheet metal work, wiring, grinding, fabricating, component replacement, complex welding, fabric work, anti-corrosion, alignment, and tuning.

C-123 crew members were issued Nomex™ flight suits, jackets, and gloves that were similar to those worn by other airplane crews. The Nomex™ flame resistant flight suits were not designed to protect the flight crews from chemical exposures; gloves could be removed and sleeves could be rolled up. After flight, the suits were handled, laundered, and stored by the individual crew members. Because C-123 aircraft were neither heated nor air-conditioned, winter operations typically required long johns, parkas or winter flight jackets, wool watch caps, and winter flying boots. No hazmat gear was issued, but maintenance personnel would wear appropriate protection for specific ground tasks (for example painting, cleaning or filling fuel tanks, or working with anti-corrosives).

Reservists typically brought their meals with them on flights, which were stored in the cooler tail sections of the aircraft because no refrigeration facilities were on board. Meals, which were usually sandwiches, were consumed while in flight. Fresh coffee and water were provided for each flight. There were no sanitation facilities inside the aircraft and only moist towlettes were available for personal hygiene.

The committee notes that a considerable amount of information necessary for meaningful quantitative estimation of the Reservists’ exposure proved not to be recoverable at all or remained resistant to reconciliation of the content provided by various sources. For instance, considerable effort by a number of parties has failed to establish exactly how many C-123s the military had in Vietnam; how many were used for spraying herbicides (the ones referred to in this report as ORH C-123s); how many sprayed only insecticides; how many were returned to the United States; how many ORH C-123s and how many C-123s that had not been in Vietnam were allocated to the various reserve units.

CONCERNS ARISE ABOUT EXPOSURE TO HERBICIDES

Air Force Health Study

In 1979, a commitment was made by the AF to study potential adverse health effects in ORH personnel (AFHS, 1982). No exposure information was available for this cohort; no air or wipe samples were taken from ORH aircraft while being used in Vietnam. After an extended peer review process, the Air Force Health Study (AFHS) protocol was approved in 1982 calling for a matched-cohort design in a nonconcurrent prospective setting to evaluate morbidity, mortality, and reproductive health in ORH veterans (AFHS, 1982). The AFHS protocol called for six comprehensive physical examinations to be completed within a 20-year period.

According to an AF Working Paper prepared by the USAF School of Aerospace Medicine, the AF Reserve population was initially considered as a comparison population for the AFHS, but was dropped from consideration because the population was too small (identified as less than 3,000 people) and because “many of the Ranch Hand aircraft were reconfigured for transport and insecticide missions and thus, non-Ranch Hand crews responsible for these other missions, may have been exposed to significant Herbicide Orange residues in these aircraft . . . this group may not have been truly unexposed to herbicides, and was discarded as an appropriate control population” (AF Working Paper, 1979, p. V-4). AF personnel who flew C-130 aircraft in Southeast Asia during the same time as ORH personnel were eventually selected as the comparison population for the AFHS.

The initial study population consisted of 1,269 ORHs and 24,971 comparison veterans, nonexposed AF veterans who served in Southeast Asia between 1962 and 1971 (AFHS, 1983). During the course of the six examination cycles—in 1979, 1982, 1987, 1992, 1997, and 2002—more than 80,000 biological specimens were collected and stored and 1,800 serum TCDD concentrations were measured in ORH veterans who had blood draws (AFHS, 1991, 1995, 2000; Robinson et al., 2006).

Although several epidemiologic studies were published on AFHS physical examination results, few significant findings have been reported in ORH veterans. Diabetes, described as “the most important dioxin-related health problem seen in the AFHS,” was found to be 21% higher in AFHS participants when compared to the comparison group (AFHS, 2005; Michalek and Pavuk, 2008). The various epidemiological studies of the ORH cohort generally lack the power to detect elevated cancer rates consistent with doses reconstructed from biomonitoring and the carcinogenic slope factor last endorsed by US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA, 2012). Therefore, lack of positive epidemiological evidence in ORH personnel (itself a matter of some dispute) does not preclude an elevated carcinogenic risk for the AF Reservists, particularly because TCDD has been found to be carcinogenic to humans by the International Agency for Research on Cancer (McGregor et al., 1998) and no safe level has been determined.

The experience of ORH personnel, both during their service in Vietnam and as participants in the AFHS, provides important historical context for how C-123 aircraft became contaminated with herbicides and how the unique exposure of the ORH cohort may have impacted their health. It must be noted, however, that the experience of ORH personnel is peripheral to the current committee’s charge. This Institute of Medicine (IOM) committee is charged with examining the potential exposure of AF Reserve personnel who worked and trained aboard C-123 aircraft that were used by ORH personnel for herbicide spray operations in Vietnam. The determination of any potential exposure—or level of exposure—of AF Reserve personnel were considered by an evaluation of data that is directly

relevant to their unique exposure opportunity. Their daily work environment was aboard C-123 aircraft that were formerly used to spray herbicides and samples taken of these aircraft indicate that chemical residues remained. The potential exposures for AF Reserve personnel were evaluated strictly on that basis by this committee, not by direct extrapolation from the health experience of ORH personnel.

RESIDUAL CHEMICALS IN FORMER ORH AIRCRAFT

Existing Sampling Data

“Patches” Sampling Data (1975, 1979)

Among the C-123s used by AF Reserve personnel between 1972 and 1982, was “Patches” (aircraft tail number 56-4362). “Patches” was hit more than 500 times by enemy ground fire while being flown for ORH defoliation missions in Vietnam, and earned its nickname for the numerous metal patches applied to cover and repair its many holes (Cecil and Young, 2008). Most flight records and historical documents provided to the committee indicated that “Patches” flew herbicides missions in Vietnam from 1961–1965 (USAF, 1979; Young and Young, 2014a); although at least one record reproduced from the USAF Historical Records Research Agency indicated that “Patches” was not converted to spray herbicides or insecticides until 1967 (Carter, 2013). After 1967, “Patches” was assigned to insecticide spray missions in South Vietnam as part of Operation FLYSWATTER (Young and Young, 2014a).

Several AF Reserve personnel recall flying on former ORH C-123s that had an “overwhelming chemical smell,” and “Patches” was one of the C-123s reported to have objectionable chemical smells in its cabin (Battista, 2014; Carter 2013; Cecil and Young, 2008). Although TCDD is odorless and colorless, Cecil and Young (2008) described “Patches” as “reeking of malathion” that remained after years of spraying the insecticide while flying in Vietnam as part of Operation FLYSWATTER. Accounts from AF Reserve personnel, however, identified the odor as being from AO residue remaining in the aircraft (Battista, 2014; Carter, 2013).

In 1975, a “black, viscous, odorous residue” was found in “Patches” while it was undergoing a depot level wing modification at Hayes International Corporation in Dothan, Alabama. A sample of the residue, analyzed by the USAF Environmental Health Laboratory at Kelly AFB, was determined to be malathion; no “Herbicide Orange” was identified in the sample (USAF, 1979). Detailed results from this analysis were not made available to the committee.

In April 1979, after crews from the 439th Tactical Air Command Hospital complained about chemical odors while flying in “Patches,” air and scrape samples were collected and evaluated for Herbicide Orange (specifically testing

for 2,4,5-T and 2,4-D) and malathion (USAF, 1979). Surface loadings and air concentrations determined that 2,4,5-T butyl ester and 2,4-D isooctyl ester were present at sub mg/m3 quantities in the air and in paint scrapings (90 to 150 µg/kg) from cargo tie-down rings, documenting that these phenoxy herbicides were still present in the aircraft (see Table 3-2). The phenoxy herbicides 2,4-D butyl ester and 2,4-D isooctyl ester were components of AO and AO II, respectively, which were sprayed in Vietnam by ORH. Based on the records of sampling, these three air samples were collected over a 5-hour period while the aircraft was stationary. The air samples were collected using chromosorb (c1-2), which collects the vapor phase and (because no filter was specified in front of the tube) particulate matter. TCDD was not analyzed in the air or in paint scraping samples in 1979 (because sufficiently sensitive analytic methods for identifying dioxin would not be developed until the 1980s, and even then the cost to analyze each sample was on the order of $1,000). The AF reported that the test results were low enough to “indicate no health hazard.”

TABLE 3-2 Interior Sampling for Phenoxy Herbicides of C-123 Planes Used in Operation Ranch Hand

| Source | C-123 Tail Number | 2,4,5-T | 2,4-D | Location | |

| Herbicide Air Samples (mg/m3)a | |||||

| USAF (1979) | 56-4362a, b | 0.14 | 0.11 | Front starboard, 3 ft. above floor | |

| 0.19 | 0.23 | Middle port, 3 ft. above floor | |||

| ND | ND | Rear starboard, 3 ft. above floor | |||

| USAF (2009b) | 55-4532 NDc | NDc | Interior | ||

| 55-4571 NDc | NDc | Interior | |||

| Herbicide Scrape Samples (µg/kg) | |||||

| USAF (1979) | 56-4362b | ~ 150d | ~ 92e | Cargo tiedown ring, center of plane | |

| < 60f | < 60e | Cargo tiedown ring, center of plane | |||

| Herbicide Wipe Samples (µg/m2) | |||||

| USAF (1996) | 54-0607 | 2,600 | 3,400 | Spray line, right | |

| < 95 | < 81 | Floor, right | |||

| 54-0618 | 130 | < 81 | Sprayline, left | ||

| < 95 | < 81 | Floor, right | |||

| 54-0586 | 1,400 | 8,600 | Spray line, right | ||

| 280 | 430 | Floor, right | |||

| 54-0628 | < 95 | < 81 | Sprayline, left | ||

| < 95 | < 81 | Floor, right | |||

| Source | C-123 Tail Number | 2,4,5-T | 2,4-D | Location |

| 54-0693 | — | — | Spray line, right | |

| 2,600 | 3,100 | Floor, left | ||

| 54-0701 | 1,000 | 7,700 | Spray line, right | |

| < 95 | 100 | Floor, right | ||

| 55-4520 | 290 | 240 | Spray line, left | |

| 1,400 | 2,200 | Floor, left | ||

| 55-4532 | 560 | 1,100 | Spray line, right | |

| 430 | 650 | Floor, right | ||

| 55-4571 | < 95 | 130 | Spray line, right | |

| 650 | 600 | Floor, right | ||

| 55-4577 | 41,000 | 38,000 | Spray line, right | |

| 220 | 140 | Floor, right | ||

| 56-4371 | 1,500 | < 900 | Sprayline, right | |

| 220 | < 81 | Floor, left | ||

| 55-4547 | < 95 | < 81 | Spray line, right | |

| < 95 | < 81 | Floor, right | ||

| USAF (2009b) | 55-4532 | 1,000 | 810 | Interior floor-1 |

| 100 | < 500 | Interior floor-2 | ||

| 240 | 140 | Interior floor-3 | ||

| 1,100 | 1,200 | Interior floor-4 | ||

| 650 | 560 | Front bulkhead wall | ||

| 37 | < 500 | Interior ceiling (between wings) | ||

| 390 | 450 | Interior rear frame | ||

| 55-4571 | 490 | 540 | Interior floor-1 | |

| 100 | 110 | Interior floor-2 | ||

| 360 | 520 | Interior floor-3 | ||

| 310 | 250 | Interior floor-4 | ||

| 260 | 180 | Front bulkhead wall | ||

| 600 | 1,600 | Interior ceiling (between wings) | ||

| 720 | 100 | Interior rear frame-1 | ||

| 840 | 780 | Interior rear frame-2 | ||

| 980 | 1,200 | Interior rear frame-3 | ||

a The air sampling methods used on these two occasions differed, so results are not fully comparable.

b C-123, Tail Number 56-4362 is known as “Patches.”

c Detection limit not provided.

d Detection limit provided but in incorrect units. Stated as 1 µg/100 m2 for 2,4,5-T and 4 µg/100 m2 for 2,4-D.

e Butyl ester.

f Isooctyl ester.

“Patches” Sampling Data (1994, 1995)

In 1980, the Air Force moved “Patches” to museum status and transferred the aircraft to the USAF Museum (renamed the National Museum of the USAF in 2004) located at the Wright-Patterson AFB in Dayton, Ohio, where it was displayed outside because of residual chemical odors (Cecil and Young, 2008). Additional sampling of “Patches” was undertaken in 1994 when plans were under way for repair work to the aircraft and it was slated to be moved to an indoor display at the museum. For the protection of aircraft restoration personnel, wipe samples were taken from the interior and exterior of the aircraft prior to starting restoration efforts. There was some indication that the sample collection sites were in the section of the aircraft where AO is likely to have been spilled or leaked during spray operations (USAF, 1994). Sampling locations were from “areas of limited traffic near the agent orange spraying equipment” and these areas were “somewhat protective of routine crew movement and routine historical maintenance” (USAF, 1994). The 1994 sampling found TCDD in the interior of the aircraft, but not on the exterior. The absence of TCDD on the exterior is consistent with its photo-degrading in sunlight. The three interior TCDD measurements spanned a wide range (200 to 1,400 ng/m2) (see Table 3-3), and were determined to likely “be representative of other locations of limited traffic near the agent orange spraying equipment,” but not considered to be “indicative of the surface contamination throughout the entire cargo area of the aircraft” (USAF, 1994). As a result of the 1994 sampling, “Patches” was determined to be “highly contaminated” with polychlorinated dibenzodioxins (USAF, 1994). Restoration work was recommended for decontamination of the aircraft using protective equipment and processes for containment of contaminated dust. Thereafter, public entry was prohibited (USAF, 1994).

In a letter to the editor by Nieman (2014) concerning an article about potential exposures aboard former ORH C-123s by Lurker et al. (2014), it was revealed that there had been additional sampling of “Patches” in 1995; information about this episode of sampling and the results (USAF, 1995a,b,c) were provided to the committee on May 15, 2014. Samples collected in 1995 from “Patches” were analyzed as composite samples of between three and six wipe samples. Each group was collected from different sections of the aircraft, five from the interior sections and five from exterior sections. Four of the interior composite samples, collected from the front and mid-section of the aircraft were below detection limits (< 12 to < 20 ng/m2). The fifth interior composite sample, collected from the rear of the aircraft, found a concentration of 30 ng/m2. The 1995 sampling results are presented in Table 3-3.

The reason for the substantial differences in TCDD surface loadings measured in 1994 and 1995 in “Patches” are unclear. There could have been unidentified inconsistencies in sampling or analysis methods. No details on the collection protocols for the 1995 samples were provided. If a dry or water wipe was used

TABLE 3-3 Interior Sampling for TCDD of C-123 Planes Used in Operation Ranch Hand

| Source | C-123 Tail Number | Concentrationa | Location |

| TCDD Air Samples (pg/m3) | |||

| USAF (2009b) | 55-4571 | < 4.5 | Interior |

| 55-4532 | < 4.1 | Interior | |

| TCDD Wipe Samples (ng) | |||

| USAF (1996) | unknown | 0.21b | Auxiliary power unit |

| 6.9b | Metal railing top of tank | ||

| TCDD Wipe Samples (ng/m2) | |||

| USAF (1994) | 56-4362c | 200 | Horizontal surfaces “from areas |

| 250 | somewhat protective of routine | ||

| 1,400 | crew movement” | ||

| USAF (1995a,b,c) | 56-4362c | 30 | Interior rear |

| < 15 | Front port | ||

| < 12 | Front starboard | ||

| < 20 | Center port | ||

| < 13 | Center starboard | ||

| USAF (2009b) | 55-4532 | 24 | Interior floor-1 |

| 25 | Interior floor-2 | ||

| 28 | Interior floor-3 | ||

| 12 | Interior floor-4 | ||

| 4.8 | Front bulkhead wall | ||

| 8.1 | Interior ceiling (between wings) | ||

| 13 | Interior rear frame | ||

| 55-4571 | 18 | Interior floor-1 | |

| 27 | Interior floor-2 | ||

| 21 | Interior floor-3 | ||

| 4.3 | Interior floor-4 | ||

| 7.1 | Front bulkhead wall | ||

| 1.0 | Interior ceiling (between wings) | ||

| 9.3 | Interior rear frame-1 | ||

| 32 | Interior rear frame-2 | ||

| 10 | Interior rear frame-3 | ||

a It might have been preferable to consider TCDD results in terms of Toxicity Equivalency Quotients (TEQs) from all dioxin, furan, and PCB congeners with “dioxin-like activity” through the aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AHR), as did Lurker et al. (2014). However, TEQs were not available from the 1995 and 1996 TCDD sampling events; results of the 1995 sampling were made known only after the publication of Lurker et al. (2014), and, for the reason explained in the next footnote, the 1996 sampling results were not suitable for use in calculating exposure.

b Collected samples were positive for TCDD, but area sampled was not reported so loading (mass/area) cannot be calculated.

c The C-123 with tail number 56-4362 is known as “Patches.”

rather than a solvent (hexane) wetted wipe, then the results would be expected to be lower. The original contamination was not uniform throughout the interior of the aircraft. Any loss by degradation or cleaning also may not have functioned evenly over the surfaces, thus making the very limited number of samples susceptible to perturbation by “hot spots.” As noted in Chapter 2, TCDD and herbicides are semi-volatile, and so can be redistributed within the aircraft from volatilization/deposition with heating and cooling of the aircraft left outside the sun. Unlike the two C-123s sampled in 2009, “Patches” had not spent an extended time sealed up on the desert, so it would not have experienced this phenomenon that would contribute to more uniform distribution of the contaminants throughout the interior. “Patches” was thoroughly washed and decontaminated after this sampling effort took place, after which “no dioxin contamination was detected” (USAF, 1997a).

Sampling of Planes at Davis-Monthan AFB, Arizona (1996)

Between 1981 and 1986, 18 C-123 aircraft were retired to MASDC at Davis-Monthan AFB in Arizona (now called the 309th Aerospace Maintenance and Regeneration Group [AMARG]) for storage or possible sale. Of the 18 C-123 aircraft at MASDC, 13 were documented as having been used for ORH. For the remaining five (tail numbers 54-583, 54-585, 54-635, 54-685, and 55-4544), the records for one indicate that it had been used for spraying herbicide in Southeast Asia but not as part of ORH, three had no records suggesting they had ever been in Southeast Asia, and one had no aircraft records available (USAF, 2009a). Table B-1 (in Appendix B) provides a record of all 40 ORH aircraft that have been identified.

In May 1996, two wipe samples were gathered from the top of the auxiliary power unit and from the metal railing on top of the tank from one or two planes (no specification of aircraft tail number specified) and subsequently analyzed for TCDD (USAF, 1996). The measurements reported were 210 pg and 6,900 pg, but because the size of the surface area sampled was not provided, the surface loading could not be calculated (see Table 3-3). Wipe samples for 2,4-D and 2,4,5-T analysis were also collected using moist Whatman (6″× 6″) glass fiber filters from 17 of the 18 aircraft, of which 12 were ORH C-123s. The samples were collected from the floors under the spray line caps to evaluate the area likely to have had the maximum original deposition. Herbicides were detected in all the ORH aircraft (0.13 to 41 mg/m2) (see Table 3-2). The presence of AO constituents in the 12 ORH C-123s 22 years after returning from Vietnam clearly demonstrated the lingering contamination of AO constituents, presumably including TCDD.

ORH Planes Sampled at Davis-Monthan AFB, Arizona (2009), and Disposition of C-123 Aircraft

After more than 20 years in storage at MASDC, the decision was made by the AF to recycle and dispose of the former ORH C-123 aircraft. Prior to the recycling, the AF sampled the planes “in the event of future liability issues and to protect personnel that may be involved in the recycling process” (USAF, 2009c). Four of the 18 C-123s were sampled using air sampling methods and wipe sampling for phenoxys (USAF, 2009a). Of these, two did not have documentation of having been used in ORH (tail numbers 54-0585 and 55-4544). Samples were collected from 100 cm2 areas with pads wetted with hexane. Multiple locations were sampled in each aircraft. After analyzing 16 individual wipe samples, detectable levels of TCDD (with range of loadings on the floors from 4.3 to 28 ng/m2 [mean 20 ng/m2]) were detected in the two C-123 aircraft known to have been used in ORH and also found positive for phenoxys in 1996. TCDD loadings on other surfaces (wall, ceiling, rear frame) ranged from 1.0 to 32 ng/m2 (see Table 3-3), whereas the two C-123 aircraft that did not have detectable TCDD were later determined to have no record of having sprayed herbicides in Vietnam (USAF, 2009b). The two planes with known use in ORH had mostly detectable levels of phenoxy herbicides (see Table 3-2).

In April 2010, the 18 C-123 aircraft stored at Davis-Monthan AFB were smelted at an off-base contractor-operated smelting unit for conversion to aluminum ingots (Young and Young, 2014a). Of the ORH C-123s identified in historical documents, only three remain in the United States. Those aircraft are located at museums in Delaware, Georgia, and Ohio (details in Appendix B, Table B-1).

Overall, when specified, the current documentation indicated valid collection methods and valid analytical protocols were followed. For estimating the loading on the surfaces, the committee decided that only data collected from aircraft used in ORH should be included. While the sampling sites were not equally distributed across all aircraft or locations within the aircraft, the committee considered all data available, particularly in light of the limited amount of sampling conducted on C-123 aircraft used in ORH, with concern for health risks focused on TCDD.

RETROSPECTIVE ESTIMATION OF CONCENTRATIONS FROM THE FULL SET OF WIPE SAMPLES

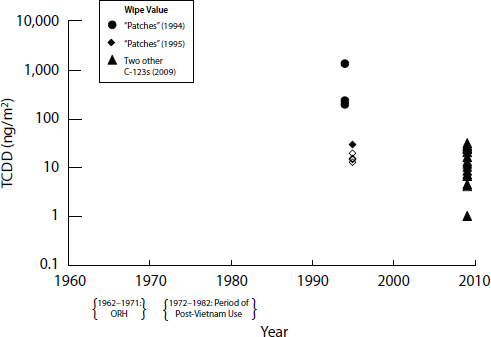

The measurements of TCDD from various interior surface locations on “Patches” or the other C-123 planes were variable (see Table 3-3). TCDD concentrations in surface wipe samples collected in C-123s between 1994 and 2009 ranged from 1,440 ng/m2 in 1994 down to 1 ng/m2 in 2009. The range among the 1994 samples alone was almost an order of magnitude (200–1,440 ng/m2) (see Figure 3-1). Regardless of the actual reconditioning process for former ORH

FIGURE 3-1 TCDD surface concentrations from interior wipe samples. NOTE: TCDD surface concentrations obtained from the total of 24 wipe samples from the interiors of ORH C-123 aircraft by year. Clear points represent non-detect samples plotted at their detection limit.

C-123 aircraft were tested for herbicide or dioxin contamination soon after they returned from Vietnam.

The committee noticed the singularly high TCDD value of 1,400 ng/m2 reported in “Patches” in 1994. The samples collected in the same aircraft the following year had values considerably lower, with several below detection. These variations lead to uncertainty in estimating the actual exposures of the AF Reservists, but confirm that TCDD exposure would be expected. While some samples were collected in areas that are suggested to have had little traffic, the work patterns of the AF Reservists and the different configurations of equipment and personnel used in flight assignments led to the committee’s judgment that contact with these surfaces carried a risk, though not quantifiable, of harmful exposure to the AF Reservists.

A number of limitations in these data are obvious. Samples were analyzed for TCDD only four times; 1994 and 1995 (from “Patches”), 1996, and 2009. The samples from “Patches” appear inconsistent, as far higher levels were found in

1994 compared to 1995 (the highest level measured in 1995 [30 ng/m2] is more than 20-fold lower than the average level measured in 1994 [617 ng/m2]). A major limitation is that the earliest TCDD samples were collected in 1994, roughly 20–25 years after these planes were returned from Vietnam and more than 10 years after their retirement from use by the AF Reservists in 1982. The committee agreed that the TCDD interior wipe samples were the most informative data available, although all of the TCDD samples from C-123s that were known to have been used in ORH came from a total of only three planes. Other aircraft known to have been used in ORH were not sampled for TCDD. The sampling sites within the planes were highly variable, and important details regarding collection and analysis methods were often found to be missing (see detailed discussion of samples above).

In addition to these TCDD wipe samples, air samples were collected in 2009 and analyzed for TCDD, all of which were non-detects, and samples from various media were collected and analyzed for 2,4-D and 2,4,5-T in 1979 and 2009 (see Table 3-2).

Clearly, any results of quantitative evaluation of potentially harmful TCDD exposures during the period of ORH C-123 use by the AF Reservists from such sparse and possibly inconsistent exposure data will be very uncertain. Therefore, the committee was unable to extrapolate with any confidence the levels of TCDD expected in the C-123s during 1972–1982 when exposure of the AF Reservists might have occurred.

Assuming there were no additional sources of TCDD contamination once the C-123s were returned to the United States, the discovery of residues long after ORH implies that degradation of TCDD was much slower within the planes than on their exteriors, which were exposed to sunlight and open environments. There is little doubt that TCDD surface levels in the late 1970s and early 1980s were higher than those in 1994, 1995, and 2009, and thus levels measured in these later years likely represent a lower bound on levels the AF Reservists might have been exposed to.

These factors led the committee to conclude the following:

Detection of TCDD long after the AF Reservists worked in the planes means that surface levels at the time of their exposure would have been at least as high as the available measurements, and quite plausibly considerably higher.

The resulting measurements of interior surface sampling in 1994, 1995, and 2009 most likely represent a lower bound, at least in terms of order of magnitude, of unit values of ng/m2 for what the surface concentrations might have been when AF Reservists worked in the planes.

ASSESSMENT OF VALIDITY AND UTILITY

Wipe Samples

The ability of a wipe sample to capture true surface loadings is limited in many respects. It is likely that wipe sample data can differ, depending on the methods used in their collection (EPA, 1991) (i.e., different samplers, wiping material, solvent, or lab analyses), resulting in a wide range of values. In addition, there is variability due to specific characteristics of the sampled surfaces (e.g., porosity, texture, orientation) (CHPPM, 2009; EPA, 1991). The Environmental Protection Agency (1991) holds that even if adequate sampling is achieved, results are not always reproducible and estimates from wipe samples may indicate levels that are “substantially below true surface levels.”

The utility of the wipe sampling of the C-123 aircraft is also reduced by the limited number of aircraft sampled and a limited number of surfaces sampled within each aircraft. For sampled surfaces, there is little information regarding the texture or porosity. Additionally, these samplings were conducted decades after the applicable time period of potential exposure. Sample collection methods were frequently either not reported (e.g., no mention of a wetting agent) or incompletely reported (e.g., solvent used is reported, but not the volume used), suggesting that methodologies across sampling periods were likely not uniform.

Air Samples

Air sampling methodologies vary depending upon whether the target compounds are expected to be present in the vapor or particle-bound phase. Particles are typically captured using filters that lack sorption capacity for vapor phase compounds. Vapor phase compounds are typically captured using a sorbent (porous polymer, polyurethane foam [PUF], etc.). Either type of sampler is encased in a cartridge with inlet and outlet ports through which air is drawn at a known rate. Sorbent cartridges will incidentally also capture particles, but are not considered reliable or quantitative for that purpose. When materials are expected to be present in both phases, use of a collection device consisting of a particle filter followed by a sorbent is standard practice.

Only very limited air sampling data were collected in the effort to understand potential post-Vietnam exposures in the C-123 aircraft. In 1979, air samples were collected from a single plane at Westover AFB in Massachusetts and analyzed for AO herbicides (and malathion). In 2009, particle samples were collected for herbicide analysis and vapor samples were collected for TCDD analysis from two ORH planes at Davis-Monthan AFB in Arizona.

The air sampling conducted in 1979 involved single air samples in three locations (sampled more or less simultaneously) within a single aircraft (tail

number 56-4362) (USAF, 1979). The samplers utilized only a porous polymer sorbent (Chromosorb C-102). The samplers were operated for 5 hours at 0.74 liters per minute (lpm), producing sample volumes of approximately 0.2 m3. The recorded temperature was 61°F and the elevation of Westover AFB is 243 feet above mean sea level. Two of the three samples revealed air concentrations of 2,4-D and 2,4,5-T that were near or above estimated vapor saturation concentrations of the acid moieties. However, the 2,4-D and 2,4,5-T esters have higher vapor pressures than the acids, and analysis of a scrape sample did reveal the presence of ester forms. Thus, the third sample was reported as non-detect, but a method quantitation limit was not reported. The third sample result is questionable. The samplers were all located within the open cargo area of the plane. Extreme concentration gradients are not plausible. The discrepancy is likely explained by sampling error (e.g., failure to collect or extract the non-detect sample) or an inadequate margin between the detection limit of the method and vapor saturation concentrations of the target compounds (i.e., poor sampling design). As noted above, measurable levels of 2,4-D and 2,4,5-T esters were found in a single surface sample collected by scraping, so despite the fact that no herbicides were detected in one of the air samples, a preponderance of the evidence suggests that herbicide was present in the air inside the plane during the 1979 sample collection.

In February 2009, additional air samples were collected from two other ORH C-123s (tail numbers 55-4532 and 55-4571) at Davis-Monthan AFB (USAF, 2009b). The temperature was not reported, but the average high and low temperatures in Tucson in February 2009 were 41°F and 75°F. The elevation of Davis-Monthan is approximately 2,700 feet above mean sea level. Herbicide samples were collected using Method 5001 of the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. This technique utilizes a glass fiber filter alone and does not capture vapor phase compounds. It is designed for capture of dusts of 2,4-D acid and 2,4,5-T acid. It does not capture the ester forms of the phenoxy herbicides. Samples were collected for 60 minutes at 2 lpm producing a sample volume of approximately 0.12 m3. Results were reported as non-detect. Stated detection limits were roughly 8 and 30 µg/m3 for 2,4,5-T and 2,4-D, respectively. Given that numbers in that range correspond to total suspended particulate concentrations encountered routinely in indoor environments such as homes and offices, and that sampling at Davis-Monthan was in planes not in active use (i.e., unoccupied), the sampling strategy may not have been sufficiently sensitive to detect herbicide unless the dusts captured approached 100% herbicide.

Air monitoring for TCDD on the two planes at Davis-Monthan in February 2009 followed EPA method TO-10a, which is a low volume PUF method for pesticides and PCBs. Sampling was conducted for 4 hours at 4 lpm, producing sample volumes of approximately 1 m3. In contrast, the EPA method for PCDDs, TO-9a, specifies a sample volume of 325–400 m3. Results were reported as non-detect for 2,3,7,8-TCDD in all four planes sampled. Detection limits of 0.5–4 pg/m3 (0.0005–0.004 ng/m3) were reported for TCDD. Documentation

of quantitation limits was not provided and no positive (spiked) controls were reported. Therefore, evidence of extractability of TCDD from PUF using the applied methods was not provided. Per EPA method TO-10a guidance, detection limits of 0.001–50 µg/m3 (1–50,000 ng/m3) are expected with sampling times of 4–24 hours. Although limits are compound specific, the low end of that range is roughly 1,000 times higher than the detection limit claimed in the Davis-Monthan report.

These samples were collected to assess whether there was a significant exposure risk to personnel who were going to be involved in the destruction and recycling of the aircraft over a short period of time, rather than for exposures continuing over years, as was the situation for the AF Reservists. Also, given the low vapor pressure of TCDD, the unknown sampling temperature (vapor pressure declines with temperature), the high elevation of the site (lowered total pressure), lack of active personnel in the plane, and the extended period since service in Vietnam, the air sampling protocol was not appropriate to estimate inhalation exposure to the AF Reservists.