Key Findings

- While many young adults gain enough education and labor market experience to succeed in life, doing so has always posed some challenges for other young adults, especially those from economically disadvantaged or minority backgrounds. These challenges are greater today than in earlier eras, and not only for those whose families have been disadvantaged.

- The cost of college has grown substantially, and many students have difficulty making the investment, yet prospects for well-paying jobs for high school graduates without some postsecondary credentials are slim. For this and other reasons, many young adults enter college, but dropout rates are high, and the numbers of years needed to complete degree programs have risen.

- Well-compensated entry-level jobs are becoming more difficult to find, even for young college graduates, and especially in the aftermath of the Great Recession. Moreover, many companies do not provide health insurance or other economic benefits, and low earnings plague many young workers because of technological change and globalization, as well as the weakening of institutions and mechanisms (such as unions and government regulations) that have traditionally protected less-educated workers.

- Educational attainment during young adulthood has lifelong implications not only for economic well-being but also for health. Over the long run, the more educated a young adult becomes, the healthier she or he will be in adulthood.

- Given the important linkages among education, employment, and health and safety outcomes for young adults, the very weak education and employment outcomes of two groups of young adults raise particular concern: those who are disconnected and those who have disabilities and chronic health conditions.

- Overall, there is some evidence on successful workforce programs for adults and youth with relatively strong basic skills, and limited evidence on programs designed to improve success rates for disadvantaged students who enroll in college. Integrating useful labor market information or training into developmental efforts appears highly promising. But the ability to replicate and scale up the best programs and to identify successful efforts for those with greater skill deficiencies or disabilities remains limited.

Social scientists view the transition to adulthood as a function of progression in five interrelated domains: completing education, gaining full-time employment, becoming financially independent from parents, entering marriage/romantic partnership, and becoming a parent (IOM and NRC, 2013; Shanahan, 2000). There is agreement that all of these tasks of adulthood are now taking longer to accomplish than in generations past. Among the challenges young people face as they transition to adulthood, two can be considered centrally important: (1) progressing toward and completing their educational attainment, and (2) becoming employed and earning enough to gain independence from their families. From a developmental perspective, the transition to adulthood is a critical period for forging work- and career-related identities, with initial plans and training confronting market realities. Those who cannot gain a foothold in the world of work during this time may continue to lag behind their more successful age-mates. Thus, reflecting one of the major themes of this report, what happens during young adulthood is integral to long-term socioeconomic trajectories.

Not only is working an important aspect of becoming adult, but employment and health, including behavioral health, are highly correlated across individuals:

- Individuals with compromised health have greater difficulty attaining and maintaining employment, and involuntary loss of employment can have a negative impact on physical and behavioral health when it occurs among adults (Fergusson and Horwood, 1997; Montgomery et al., 1999; Paul and Moser, 2009).

- One study found that psychological health in childhood had a greater impact than physical health in childhood on adult earnings (Goodman et al., 2011). Psychological health problems in childhood reduce adult incomes by 14-28 percent compared with controls. Moreover, this study found that the impact of childhood psychological problems on adult income occurred disproportionately in earlier rather than later adulthood, supporting the notion that young adulthood is a critical window for intervention.

- Health care coverage is disrupted by loss of employment, and loss of coverage can contribute to reduced health care seeking, as discussed in Chapter 6.

To some extent, gaining enough education and labor market experience to succeed has always posed some challenges for young people, especially those from disadvantaged or minority backgrounds. In many ways, however, these challenges appear to be greater today than in earlier eras for a variety of reasons, and not only for those whose families have been disadvantaged.

For one thing, the labor market today poses serious challenges for young people. The Great Recession, which began formally at the end of 2007 and ended in mid-2009, reduced employment opportunities for youth and young adults more than for any other age group. Furthermore, the recovery from this recession has been both modest and extremely slow, especially in the job market; in 2011, the rate of employment in the population for young adults was only marginally higher than it was at the recession’s trough (Sum et al., 2014).

Gaining early work experience has been difficult for many in this environment, including those with college diplomas, and this sluggishness also limits wage gains for many who are employed. Indeed, the evidence suggests that the average young person entering the job market during a major economic downturn may be “scarred” by this experience in terms of lower average earnings for many years (Dahl et al., 2013; Kahn, 2010). Moreover, it is possible that the job market will remain weak going forward, and for years to come, if the current stagnation is more “secular” than “cyclical” in nature (Ball et al., 2014).

Even before 2007, however, the labor market had changed in a variety of ways that increased the challenges faced by young people. Because of a variety of labor market and institutional forces, the earnings of those with

no postsecondary education or training credential in the United States have stagnated or declined over time, and the earnings prospects of young people without this education or training are now very limited (Autor et al., 2008; Card and DiNardo, 2005). Of course, having this background is no guarantee of labor market success, especially for young adults in lower-paying fields or from less prestigious educational institutions. But on average, investments in higher education remain worthwhile for those who can afford to make them and are able to complete a postsecondary program of study (Oreopoulos and Petronijevic, 2013).

“A lot of my friends say, ‘you need to get an internship, you need something outside of your education, you need to volunteer’ to supplement your degree and stand out more.”*

Unfortunately, many young adults do not fit into this category. As discussed below, the rate at which young people graduate from high school remains quite low in the United States, and substitutes (such as passing a General Educational Development [GED] test) are not particularly valued in the job market. Many of those who complete high school only face poor labor market prospects. Noncompletion rates also are quite high among those who enroll in 2- or 4-year colleges. Dropout rates are particularly high at 2-year institutions and among those who are disadvantaged and have weak educational skills and records (Holzer and Dunlop, 2013).

Moreover, many people leave these institutions saddled with the debt incurred while pursuing a degree there, and are challenged to earn enough to pay down their debt while providing for themselves and their families. Failure to complete enough education or obtain a well-paying job also has some negative social consequences, such as reluctance to marry (or an inability to stay married), and incarceration rates for such young adults, especially young men of color, are unacceptably high. For young people who are “disconnected” from school and work or disabled, these challenges can be quite severe.

Below we consider these issues at greater length. First, we look at trends in employment outcomes among young people over time, as well as in enrollment, to distinguish those who are productively engaged in work or school as opposed to being “idle” or disconnected. We distinguish trends

__________________

* Quotations are from members of the young adult advisory group during their discussions with the committee.

until 2006 from those occurring more recently, with the former reflecting secular and the latter cyclical factors to a great extent. We also consider relative wages and employment rates across young people who have finished various levels of schooling.

In the next section, we look at differences in educational attainment across racial/gender groups as well as family income, and at the extent to which observed differences in employment outcomes can be accounted for by differences in enrollment or completion rates across groups and at different kinds of schools. Since community colleges are a type of institution particularly relevant for disadvantaged young people as a potential gateway to better-paying jobs, we discuss some of their unique characteristics and a set of potential reforms to financial aid or remediation programs that might render them more effective. We also consider other possible sources of education—such as for-profit colleges or career and technical programs—as alternatives to public 2- or 4-year schools with both advantages and disadvantages in their relative benefits and costs.

Next we discuss the short- and long-term implications of education and employment for health and well-being. We also discuss the social implications of students who are relatively less successful in education or employment. We give particular attention to two groups that struggle with education and employment—“disconnected” youth and those with disabilities.

In the following section, we review the policy landscape affecting education and employment outcomes of young adults. We also consider lessons learned to date from evaluation evidence.

Finally, we conclude with conclusions and recommendations for improving opportunities for young people in both higher education and the labor market.

EMPLOYMENT OUTCOMES OF YOUNG ADULTS

Since many young adults remain enrolled in college until their mid-20s or beyond, most data on those aged 16-24 focus on their rates of engagement in the productive activities of schooling and work. We therefore analyze the fractions of youth who are either enrolled, employed, or neither (usually referred to, as above, as “idle” or “disconnected”). We then offer an analysis of the levels of educational attainment, wages or earnings, and rates of employment for those aged 25-29.

Table 4-1 presents data on employment, labor force participation, and unemployment rates, as well as rates of school enrollment and idleness, for

TABLE 4-1 Percent Changes in Labor Market Measures by Demographic Group, 1980-2010

| Ages 16-19 | Ages 20-24 | ||||||

| 1980 | 2006 | 2010 | 1980 | 2006 | 2010 | ||

| Employment-to-Population Ratio | |||||||

|

Male, White |

48.5 | 38.6 | 29.8 | 76.5 | 71.7 | 65.7 | |

|

Female, White |

43.8 | 41.8 | 34.9 | 65.1 | 69.7 | 66.9 | |

|

Male, Black |

27.7 | 21.9 | 16.0 | 60.4 | 51.8 | 44.9 | |

|

Female, Black |

21.8 | 26.3 | 20.4 | 50.1 | 57.8 | 53.4 | |

|

Male, Hispanic |

42.4 | 35.0 | 25.0 | 74.8 | 74.5 | 67.1 | |

|

Female, Hispanic |

32.7 | 29.6 | 23.8 | 52.6 | 57.5 | 56.7 | |

| Labor Force Participation Rate | |||||||

|

Male, White |

55.9 | 47.9 | 40.6 | 84.7 | 79.6 | 77.8 | |

|

Female, White |

49.5 | 49.8 | 44.0 | 69.9 | 76.0 | 75.4 | |

|

Male, Black |

36.8 | 37.2 | 30.7 | 73.8 | 68.6 | 65.8 | |

|

Female, Black |

30.2 | 40.6 | 35.1 | 61.5 | 72.8 | 71.9 | |

|

Male, Hispanic |

50.5 | 45.1 | 37.6 | 83.8 | 82.4 | 80.5 | |

|

Female, Hispanic |

38.7 | 38.7 | 34.2 | 59.0 | 65.5 | 68.0 | |

| Unemployment Rate | |||||||

|

Male, White |

13.3 | 19.3 | 26.6 | 9.7 | 9.9 | 15.5 | |

|

Female, White |

11.5 | 15.9 | 20.7 | 6.9 | 8.2 | 11.2 | |

|

Male, Black |

24.7 | 41.2 | 48.1 | 18.2 | 24.5 | 31.8 | |

|

Female, Black |

27.9 | 35.3 | 41.9 | 18.6 | 20.6 | 25.8 | |

|

Male, Hispanic |

16.1 | 22.4 | 33.4 | 10.8 | 9.6 | 16.7 | |

|

Female, Hispanic |

15.3 | 23.6 | 30.4 | 10.9 | 12.3 | 16.6 | |

| Share Enrolled in School | |||||||

|

Male, White |

71.0 | 84.5 | 85.1 | 25.2 | 40.0 | 41.3 | |

|

Female, White |

70.5 | 87.4 | 88.1 | 22.3 | 46.3 | 48.5 | |

|

Male, Black |

68.8 | 78.9 | 79.8 | 19.1 | 29.4 | 31.9 | |

|

Female, Black |

70.8 | 82.3 | 83.9 | 21.7 | 37.5 | 42.6 | |

|

Male, Hispanic |

61.8 | 72.0 | 77.1 | 18.5 | 22.4 | 26.9 | |

|

Female, Hispanic |

62.1 | 78.1 | 81.8 | 17.8 | 32.3 | 36.2 | |

| Share Not in School and Not Working | |||||||

|

Male, White |

8.8 | 6.1 | 7.5 | 12.0 | 12.2 | 15.8 | |

|

Female, White |

12.4 | 5.7 | 6.1 | 25.3 | 14.4 | 15.0 | |

|

Male, Black |

17.1 | 14.5 | 15.1 | 28.9 | 33.1 | 37.1 | |

|

Female, Black |

20.3 | 11.1 | 11.1 | 37.6 | 25.8 | 26.0 | |

|

Male, Hispanic |

15.0 | 10.7 | 11.4 | 17.3 | 16.6 | 20.8 | |

|

Female, Hispanic |

22.8 | 12.9 | 11.3 | 39.5 | 29.9 | 27.9 | |

SOURCE: Adapted with permission from Dennett and Modestino, 2013.

youth aged 16-19 and young adults aged 20-24.1 The data cover the years 1980, 2006, and 2010. Changes in the period 1980-2006 reflect mainly secular trends in employment and enrollment, while those in the period 2006-2010 more likely reflect cyclical (or temporary) changes, as they indicate peak-to-trough changes in the labor market. Separate results appear by race and gender.

Table 4-1 shows the following developments for teens and young adults in the period 1980-2006:

- School enrollment rates rose considerably, especially among those aged 20-24.

- Employment rates and labor force activity fell for most groups, while unemployment rose.

- Idleness held steady or declined modestly for most groups of young men and dropped substantially for young women, whose enrollment rates rose more and employment dropped less than was the case for young men.

- Black male young adults showed a substantial increase in idleness during this period, and now have the lowest employment rates (and highest rates of idleness) of any group.

For most groups of young people, especially young women, a rise in school enrollment fully offsets their drop in employment. The larger increases in enrollment for those aged 20-24 almost certainly reflect college enrollments, and likely result in more young people with 2- or 4-year college degrees.2 Yet, reflecting a recurring theme of this chapter (and the report as a whole), these general patterns subsume a great deal of sociodemographic heterogeneity, as school and work trends vary across diverse segments of the population. For example, the rise in idleness among young black men is disturbing—especially given the fact that these data notoriously undercount less-educated young and disconnected men, especially blacks, so that actual rates of idleness and their increases over time are likely to be significantly higher for this population (Pettit, 2012). We also note the relatively low enrollment rate of Hispanic men in this age group, presumably in higher education, while their employment rate is quite high;

__________________

1 The employment rate is defined as the percentage of the civilian noninstitutional population that is employed; the labor force participation rate is the percentage of the same population that is employed or seeking work; and the unemployment rate is the percentage of that labor force that is not employed but seeking work.

2 A rise in the average number of years it takes to complete a 2- or 4-year degree also contributes to rising enrollment rates at any point in time for this population (Turner, 2007).

the implication is that their earnings growth as they age may lag behind that of other demographic groups.

The data over the period 2006-2010, on the other hand, show quite dramatic declines in employment, rises in unemployment, and declines in labor force activity for both groups, especially among teens. While some increases are seen in school enrollment (especially among Hispanics and/or those aged 20-24), these increases generally are insufficiently large to fully offset declining employment, so that idleness increased for most groups, especially male young adults.

Although unemployment rates for all groups have declined since 2010, these changes have been driven mainly by declining labor force activity rather than higher employment rates. Thus, youth employment has not rebounded strongly. Evidence has accumulated that young people who enter the job market during periods of high joblessness are scarred with low earnings in the future, and the lengthy period of depressed employment will no doubt reduce their earning capacity for many years to come (Dahl et al., 2013; Kahn, 2010). Furthermore, it is unclear whether or when these employment rates will recover, especially for those young people who have left the job market without enrolling in school.

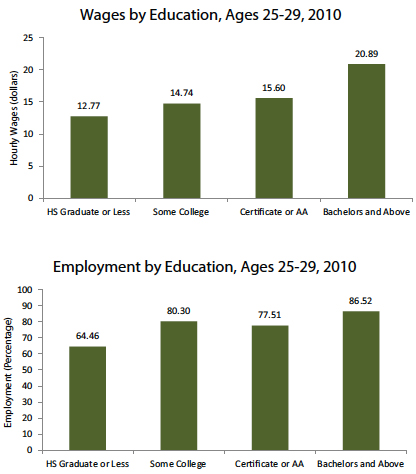

Given these patterns of school and work activity for young people until their mid-20s, what employment rates and earnings levels do we observe for young people aged 25-29? Figure 4-1 and Table 4-2 present average employment and hourly wage rates for young adults by their level of educational attainment and by race and gender in 2010. The results show large differences in both employment rates and wages across different educational groups, with both outcomes rising quite consistently with educational attainment.

It is particularly noteworthy that, since average employment and hourly wages in combination determine annual earnings, gaps in annual pay between those who do and do not have college diplomas will be substantially larger than the differences that appear in Table 4-2. It is also noteworthy that young college graduates (with BAs) have both employment and wage rates that are roughly 30 percent and 60 percent higher, respectively, than the rates for those with only high school (see Figure 4-1), implying that annual earnings are nearly twice as high for the former as for the latter. The data also show significant racial and gender gaps remaining in employment outcomes, while other data (not included here) show large variations across fields of study within each educational level.3

__________________

3 At the sub-BA and BA levels, earnings returns to degrees in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics tend to exceed those to degrees in the social sciences and humanities (and other applied fields), while returns to degrees in business, law, and medicine grow much larger at the post-BA level (Holzer and Dunlop, 2013).

FIGURE 4-1 Wages and employment by education, 2010.

SOURCE: Holzer and Dunlop, 2013, based on data from the Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP), reprinted with permission.

A substantial literature now exists that examines the trends over time in the labor market returns to different levels of education, as well as how they vary by race and gender. These studies generally show that

- earnings gaps between those with BAs and with high school only have roughly doubled since 1980 (Autor, 2010; Autor et al., 2008);

- young women have gained ground in employment and earnings relative to young men, although they still lag behind in both (Blau and Kahn, 2006);

TABLE 4-2 Employment Rate and Mean Hourly Wages by Education and by Race/Gender in 2010, Ages 25-29

| Education | Race | Gender | Employment Rate | N | Mean Hourly Wage (in 2010 $) |

| Dropout | Black | Male | 0.43 | 61 | $9.58 |

| Female | 0.33 | 107 | $9.69 | ||

| Hispanic | Male | 0.74 | 276 | $10.93 | |

| Female | 0.35 | 342 | $8.14 | ||

| White | Male | 0.73 | 302 | $12.60 | |

| Female | 0.49 | 250 | $10.12 | ||

| General Educational Development (GED) | Black | Male | 0.40 | 25 | $11.08 |

| Female | 0.56 | 60 | $11.32 | ||

| Hispanic | Male | 0.87 | 73 | $13.08 | |

| Female | 0.55 | 54 | $8.33 | ||

| White | Male | 0.56 | 214 | $15.21 | |

| Female | 0.59 | 192 | $12.55 | ||

| High School | Black | Male | 0.73 | 147 | $12.43 |

| Female | 0.57 | 159 | $9.64 | ||

| Hispanic | Male | 0.76 | 245 | $13.60 | |

| Female | 0.47 | 262 | $11.22 | ||

| White | Male | 0.83 | 905 | $16.29 | |

| Female | 0.68 | 747 | $12.14 | ||

| Some College | Black | Male | 0.78 | 161 | $13.59 |

| Female | 0.89 | 236 | $13.47 | ||

| Hispanic | Male | 0.81 | 142 | $12.55 | |

| Female | 0.66 | 221 | $13.77 | ||

| White | Male | 0.92 | 840 | $16.55 | |

| Female | 0.77 | 858 | $14.42 | ||

| Certificate | Black | Male | 0.51 | 58 | $11.45 |

| Female | 0.73 | 107 | $11.93 | ||

| Hispanic | Male | 0.89 | 56 | $12.17 | |

| Female | 0.63 | 95 | $13.81 | ||

| White | Male | 0.86 | 283 | $16.95 | |

| Female | 0.67 | 354 | $13.42 | ||

| Associate’s Degree | Black | Male | 0.90 | 22 | $11.90 |

| Female | 0.76 | 84 | $12.35 | ||

| Hispanic | Male | 1.00 | 52 | $17.03 | |

| Female | 0.74 | 61 | $16.32 | ||

| White | Male | 0.88 | 355 | $17.13 | |

| Female | 0.79 | 450 | $17.77 | ||

| Bachelor’s Degree | Black | Male | 0.96 | 36 | $20.24 |

| Female | 0.79 | 107 | $16.11 | ||

| Hispanic | Male | 0.65 | 52 | $14.94 | |

| Female | 0.70 | 84 | $15.96 | ||

| White | Male | 0.93 | 1,131 | $21.40 | |

| Female | 0.87 | 1,359 | $18.63 | ||

SOURCE: Holzer and Dunlop, 2013, reprinted with permission.

- racial differences in hourly wages among young workers within an educational category are accounted for mainly by gaps in achievement (measured as grades and/or test scores), while gender gaps (in wages and employment) reflect primarily childrearing responsibilities among women and occupational choices (Holzer and Dunlop, 2013);

- very large racial differences in employment (especially among young men) remain and are less fully accounted for by these factors (Holzer et al., 2005); and

- less-educated young white and black men have tended to withdraw from the workforce in response to these trends (Holzer et al., 2005).

Among other factors contributing to differences in employment, discrimination in hiring by race and gender has been clearly documented; “spatial mismatch” (between the locations of jobs and the residences of minorities), along with differences in the strength of informal hiring networks, contribute to employment gaps by race as well (Holzer et al., 2005). Less-educated Hispanic men work at levels above those of their white and black counterparts, reflecting some preference for immigrants in low-wage jobs among employers and also the strength of informal networks in the immigrant community. Even less-educated women have seen rising employment rates in the past two decades as a result of both employment shifts toward the service sector and policy changes. But the gaps in education and achievement across racial groups remain among the most important determinants of observed gaps in earnings (Holzer et al., 2005).

“Entering the workforce is hard because there’s this big debate over getting a job that pays well or experience. In my experience, it was either a job that was convenient, paid well, but it wasn’t really what I wanted to be doing or there was a really perfect job in my field, exactly what I wanted to be doing, but it doesn’t pay well.”

What accounts for the long-term trends in the job market for young adults? Most economists attribute these trends to ongoing technological change, whereby less-educated employees doing routine work are replaced, while demand rises for those with more technical, analytical, and/or communication skills. The forces of globalization also have gained strength in the past decade, resulting in enormous increases in the supply of less-

educated workers in international markets that increasingly compete with U.S. workers.

In addition, while the demand for higher education in the U.S. labor market has grown, the supply of workers with higher education has failed to keep pace over the past three decades (Goldin and Katz, 2009). Indeed, employers that offer substantial wage premiums for those with skills gained through higher education often are frustrated by their inability to find appropriately skilled workers in the United States. Thus they often seek such workers abroad (either by offshoring work or by lobbying for fewer limits on immigration of the highly skilled to the United States, such as through the H1-B visa program [e.g., DeLuca, 2014]). At the same time, the effects of these powerful market forces are compounded by the weakening of important institutions that have traditionally protected less-skilled workers from such market forces, such as unions and minimum wage regulation (Autor et al., 2008; Card and DiNardo, 2005).

Furthermore, job losses in the middle of the occupational wage distribution have been larger than those at either the top or the bottom. The resulting polarization of the job market has made it more difficult for less-educated workers to advance, since the production and clerical jobs that used to pay workers with a high school education well are the ones that have diminished most in number (Holzer, 2010). The results of this research do not suggest that the middle of the job market has disappeared, but that its accessibility is limited to those with at least some postsecondary education (Carnevale et al., 2010; Holzer, 2010).4

In the future, moreover, even well-educated young workers may see their skills become obsolete in a labor market buffeted by rapid technological changes and growing globalization. The need of workers to adjust their skills and careers by engaging in lifelong learning and mobility in the job market may grow accordingly.

EDUCATIONAL PATTERNS AND OUTCOMES OF YOUNG ADULTS

Because college experience is such a big part of many young adults’ lives and because the consequences of educational attainment are so important for the earnings of young adults, it is important to analyze attainment differences and trends in recent years and what accounts for them.

Young adults take many different educational paths, just as they differ widely in paths to family formation, health trajectories, and other dynamic experiences discussed throughout this report. When the type of postsecondary institution (2- versus 4-year colleges) and attendance and graduation

__________________

4 In these articles, postsecondary educational attainment can include certificates or significant on-the-job training as well as associate’s degrees.

patterns (e.g., stopout, dropout) are taken into account, no one normative pathway describes what most young people do. For example, based on national longitudinal data following high school graduates until age 25 (considering those who graduated from high school between 1977 and 2003), 47 percent graduated from a 4-year college, 12 percent graduated from a 2-year college, 11 percent dropped out, 3 percent were still enrolled, and 28 percent did not attend college at all (Patrick et al., 2013). Of particular importance, extensive variation was seen within each group of college attenders in patterns of late start, stopping out, moving between 2- and 4-year colleges, and so on (see Table 4-3). Although these rates likely will vary by historical period, the fact will remain that whenever education (and work) trajectories across the transition to adulthood are considered, there will be noteworthy heterogeneity in how young people negotiate and experience their educational pathways.

“I have a lot of friends going into engineering, simply because they think it will give them the highest chance of finding a job—not because they are passionate about it.”

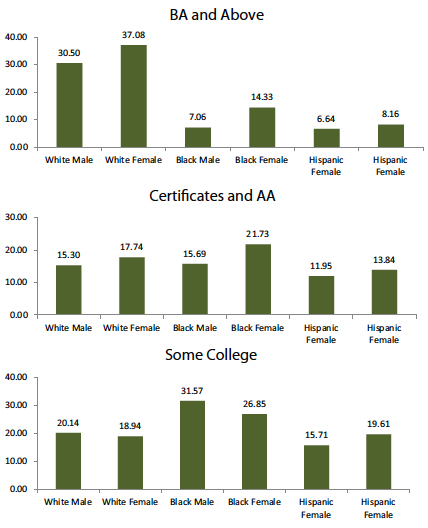

Figure 4-2 presents educational attainment trends/outcomes by race/gender as of 2010. The results show that whites still had considerably higher rates of BA attainment relative to blacks or Hispanics, although the attainment of certificates and AA degrees (and some college more generally) among blacks surpassed that among whites. Indeed, whites made substantial strides in attaining BAs during the Great Recession, while for blacks and Hispanics, the observed progress was more limited to sub-BA credentials, implying growing racial gaps in this period among those with postsecondary credentials. At the same time, young women in virtually all racial groups obtained higher education more frequently than young men.

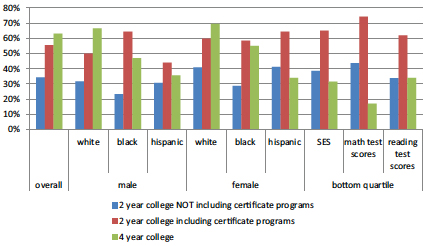

To what extent do ongoing gaps in educational attainment reflect gaps in college enrollment at the 2- and 4-year levels, as opposed to gaps in completion rates among enrollees? Enrollment rates are higher among women than men, among whites than minorities, and among middle- and upper-income families than disadvantaged ones (Holzer and Dunlop, 2013). But even larger gaps can be found in rates of college completion. Figure 4-3 presents data from the National Educational Longitudinal Study (NELS) on completion rates at 2- versus 4-year institutions for all workers and separately by race and gender and by low socioeconomic position of families in 2000. The results show average completion rates (within 6 years of enrolling) of more than 60 percent at 4-year schools, about 35 percent at 2-year schools for achieving AA degrees only, and about 55 percent at 2-year schools for achieving AAs or certificates.

TABLE 4-3 Distribution of College Attendance Patterns Among High School Graduates

| Attendance Pattern | Percent | Weighted Sample |

| 4-Year Graduates | 46.6 | 4,668 |

| Stay-ina 4-Year Graduate | 30.6 | 3,066 |

| Stay-in Combinedb 4-Year Graduate | 5.8 | 580 |

| Late-Startc 4-Year Graduate | 4.4 | 443 |

| Late-Start Combined 4-Year Graduate | 0.9 | 89 |

| Stopoutd 4-Year Graduate | 4.3 | 433 |

| Stopout Combined 4-Year Graduate | 0.6 | 57 |

| 2-Year Graduates | 11.8 | 1,184 |

| Stay-in 2-Year Graduate | 4.6 | 459 |

| Stay-in Combined 2-Year Graduate | 0.9 | 86 |

| Late-Start 2-Year Graduate | 3.9 | 395 |

| Late-Start Combined 2-Year Graduate | 0.2 | 20 |

| Stopout 2-Year Graduate | 1.6 | 161 |

| Stopout Combined 2-Year Graduate | 0.6 | 63 |

| Still Enrolled at Age 25 (Nongraduates) | 3.3 | 329 |

| Stay-in 4-Year Nongraduate | 0.2 | 21 |

| Stay-in Combined Nongraduate | 0.1 | 12 |

| Late-Start 4-Year Nongraduate | 0.9 | 91 |

| Late-Start 2-Year Nongraduate | 0.7 | 71 |

| Late-Start Combined Nongraduate | 0.2 | 17 |

| Stopout 4-Year Nongraduate | 0.7 | 75 |

| Stopout 2-Year Nongraduate | 0.1 | 13 |

| Stopout Combined Nongraduate | 0.3 | 26 |

| Dropouts | 10.8 | 1,084 |

| Immediate-Starte 4-Year Dropoutf | 5.2 | 522 |

| Late-Start 4-Year Dropout | 0.7 | 74 |

| 2-Year Dropout | 3.6 | 357 |

| Late-Start 2-Year Dropout | 0.9 | 87 |

| Combined Dropout | 0.4 | 44 |

| Never Attenders | 27.5 | 2,755 |

NOTES: Based on national longitudinal data from the Monitoring the Future study, following high school seniors (graduating classes of 1977-2003) into young adulthood; total N = 10,020.

a Stay-in refers to continuous enrollment until graduation.

b Combined refers to students who attended both 2-year and 4-year schools across the follow-up waves.

c Late-start refers to those who did not attend school until after age 19.

d Stopout refers to those who reported dropping out before returning to graduate.

e Immediate-start refers to students who enrolled the year following high school.

f Dropout refers to those who left school and did not graduate.

SOURCE: Patrick et al., 2013.

FIGURE 4-2 Educational attainment by race/gender, ages 25-29, 2010.

SOURCE: Holzer and Dunlop, 2013, based on data from the Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP), reprinted with permission.

Very large gaps exist in BA completion rates by race and socioeconomic position; more specifically, completion rates for whites exceed those for blacks and Hispanics by about 20-30 percentage points, while those in the bottom quartile of parental socioeconomic position have BA completion rates nearly 40 percentage points lower than those of other students (Holzer

FIGURE 4-3 Completion rates: Total and by demographic/achievement groups, 2000.

NOTE: SES = socioeconomic status.

SOURCE: Holzer and Dunlop, 2013, based on data from the National Educational Longitudinal Study (NELS), 2000, reprinted with permission.

and Dunlop, 2013). Indeed, some recent evidence suggests that differences in educational attainment by socioeconomic position are widening over time (Bailey and Dynarski, 2011). Female completion rates also exceed those of males among both whites and blacks (Bailey and Dynarski, 2011). As for AA (and certificate) attainment, differences in completion by race/gender and socioeconomic position are not as large as they are among BA students, but completion rates at 2-year colleges are quite low across the board (Holzer and Dunlop, 2013). While credits attained even by those who do not finish degree programs generally have some labor market value (Kreisman et al., 2013), in most cases there remains a substantial reward for attaining a degree that the noncompleters do not receive.

What might account for the large observed differences in educational attainment and completion across race/gender and socioeconomic groups? A large body of research attributes these differences to

- cognitive skill gaps reflecting highly uneven academic preparation in the K-12 years (Bound et al., 2010; Holzer and Lerman, 2014),

- rising costs of education and liquidity constraints facing families with lower levels of household wealth (Bound et al., 2010),

- poor information about educational opportunities among lower-income or minority students (Baum and Schwartz, 2014; Hoxby and Turner, 2013), and

- family obligations and pressure to generate income by working full time (Baum and Schwartz, 2014).

It is noteworthy that completion rates vary substantially across institutions as well as demographic groups of students, and are generally higher, even adjusting for student academic preparation, at the more prestigious or elite schools. Some observers have attributed these differences to resource constraints at weaker institutions that limit their ability to provide supports, or even enough key classes to accommodate differences in student needs or schedules (Bound et al., 2010). Thus to the extent that poor information among lower-income young adults leads them to be “undermatched” to colleges and universities in terms of quality, their completion rates (and labor market opportunities thereafter) are lower as well.

Another problem that has recently grown more serious is the accumulation of student debt. The ratio of outstanding debt to income for households with educational debt rose from 0.28 in 1992 to 0.6 in 2010 (Akers and Chingos, 2014). On average, college remains a very good economic investment for those who complete their chosen degree program and gain employment soon after in their chosen fields. For these individuals, the accumulation of debt makes sense, and repayment generally is not burdensome, but for individuals who drop out of college or have difficulty obtaining a job in the current economic environment, debt repayment can be quite difficult.

Of course, the ability of young adults to enroll in college at all will depend on their rates of high school graduation (or attainment of a GED credential). Thus, although most high school dropping out occurs in the earlier teen years, it is clearly relevant to the educational outcomes considered here. Dropout rates in the United States have clearly declined in the past 10-15 years (Murnane, 2013), although they remain somewhat high in comparison with those observed in other industrialized countries, especially among minorities or disadvantaged students.5

Low educational attainment also is a particularly serious problem in some geographic locales, such as inner-city neighborhoods with concentrated poverty and many rural areas. Individuals from these areas who attain more education tend to relocate elsewhere and leave behind a more disadvantaged population (Domina, 2006).

Overall, the ongoing (and sometimes growing) gaps in achievement

__________________

5 Murnane (2013) shows that the current high school dropout rate in the United States is about 16 percent, and about 22 percent among blacks and Hispanics.

and educational attainment among young adults from different family backgrounds and between whites and minorities will contribute to ongoing economic inequality in the United States and limited upward mobility for disadvantaged young adults.

Community Colleges: Multiple Roles and Challenges

Community colleges are uniquely positioned to provide both academic and vocational opportunities to young adults, especially those from disadvantaged backgrounds and/or with relatively weaker academic preparation. They can provide a gateway to more traditional higher education in 4-year schools, but also offer AA degrees or certificates (both for credit and noncredit) that have more immediate labor market value. Moreover, these schools are accessible both to young adults directly after high school graduation and to those who decide to return to school after some time away.

The success of community colleges in these different roles appears to vary substantially across institutions. Some see their traditional academic mission as primary, while others focus more on the vocational challenge. And the high rates of program noncompletion at community colleges noted above suggest that there are broad areas in which improvements are needed.

One such area is developmental (or remedial) education. Large numbers of students (perhaps more than half) enter community college academically unprepared for the rigors of postsecondary work, and they often are placed in noncredit remedial classes they must pass before they are allowed to take classes for credit (Aud et al., 2011). But evidence suggests that remedial classes may be unsuccessful in preparing many students, who instead drop out altogether in high numbers (Bettinger et al., 2013; Clotfelter et al., 2013). In some cases, there is even evidence of negative effects of remediation on educational outcomes.

Financial aid is another area in which impacts on student outcomes are not necessarily as positive as they could be. Students often face a bewildering array of federal, state, and institutional programs that provide a mix of grants, loans, and work-study. Application rules tend to be complicated, and complex interactions in eligibility often exist across the many forms of aid. And the Pell grant, the primary federal program for disadvantaged students, is simply a voucher to attend any college, accompanied by few other supports or academic conditions (Dynarski and Scott-Clayton, 2013).

More broadly, the largely unstructured and unassisted experiences of many students in community college (especially those who are disadvantaged and those who are of the first generation in their family to attend college) inhibit their ability to complete programs of study or make successful transitions to 4-year colleges or the labor market. Even the processes of choosing and registering for classes can be chaotic, with many classes not

being offered in the needed time slots and much uncertainty about which classes will best lead toward degree completion (Jenkins and Cho, 2012; Rosenbaum et al., 2006; Scott-Clayton, 2011).

Furthermore, students who manage to complete a postsecondary program may not be making the optimal choice of a field of study, given that, as noted earlier, different fields are compensated very differently in the labor market. This suggests the importance of not just academic but also career guidance and information so that students can make better-informed choices. Also important are incentives for academic institutions to be responsive to the job market by expanding instructional capacity in areas of high labor market demand (in which more students might prefer to study) and by ensuring that instructors are fully up to date in their own preparation and the curricula they teach (Holzer, 2014; Jacobson and Mokher, 2009). A lack of well-defined institutional linkages or pathways between higher education and the job market appears to contribute to these difficulties.

The growth of for-profit colleges that compete with traditional community colleges further complicates this picture. Indeed, for-profit schools now receive at least a fourth of Pell grant dollars (Deming et al., 2013). Some observers have noted that the for-profits have greater incentives to be responsive to job market needs, although questions remain about the large debts accrued by students who attend these colleges, especially those who do not complete their degree program, and about quality and marketability more broadly (Deming et al., 2013).

Finally, the growth of massive open online courses (MOOCs) could dramatically change the delivery of higher education over time, in ways that cannot yet be anticipated. Their positive effects could include reductions in the costs of higher education and greater access among minorities and the poor to courses offered at elite colleges and universities. But very little is known to date about the quality of such education, and how credentials thus generated will be valued in the job market. Ongoing experimentation and innovation in this area may provide a clearer picture of the effects of MOOCs over time.

Alternative Routes: High-Quality Career and Technical Education and Work-Based Learning

The ability of students—whether disadvantaged or not—to gain academic credentials, along with work experience, that improve their employment outcomes would likely be stronger if they had the opportunity to choose high-quality career and technical education (CTE) offered in secondary schools. Formerly known as “vocational education,” CTE in the United States has languished for several decades, at least in part because of

opposition from minority groups and the poor (Holzer et al., 2013). Their opposition stems from the low quality of many earlier programs and the concern that students were being “tracked,” often against their will, into a considerably weaker substitute for higher education. This rightfully angered the parents and representatives of minority and disadvantaged students.

However, this is not the only possibility for CTE. In many European Union countries (such as Austria, Germany, and Scandinavia), high-quality CTE enables students to graduate from secondary school and immediately have access to relatively high-paying jobs (Hoffman, 2011; Symonds et al., 2011). In the United States, a range of high-quality models being developed hold great promise for enabling students to achieve both postsecondary and labor market success, rather than one or the other. Under these models, many students would take college preparatory curricula, including rigorous math and science classes. But more of the teaching would be in the context of work- or project-based studies, in which students would gain technical and employability as well as academic skills (Holzer et al., 2013). Very importantly, students would then have a range of high-quality education models from which to choose, all of which should prepare them for both college and careers, and no students would be tracked away from college against their will.

Among the models that have been or are being developed for secondary schools in the United States are career academies—schools within broader schools that focus on a particular industry (such as health, information technology, or finance) (Kemple and Willner, 2008). Students take classes and attain work experience in their chosen field while also pursuing more general, college preparatory studies. Career academies clearly improve the employment outcomes of students, especially at-risk young men, for many years after without their having to sacrifice their academic work (see the section Evaluation Evidence in this chapter). Other promising CTE models include High Schools That Work, a model that embeds rigorous math and science instruction in a more vocational setting, and Linked Learning, in which career-oriented studies are provided for all students on a district-wide basis in California (Holzer et al., 2013).

During high school and beyond, career and technical education sometimes comes in the form of work-based learning, whereby students learn while engaging in paid work. The strongest such model is apprenticeship, in which students work for employers (at a somewhat reduced wage) while gaining important training and work experience. The education they receive is strongly contextualized by the work they perform, and they are often highly motivated to persist in and complete the program (because they are being paid to do so). Increasingly, apprenticeships incorporate a postsecondary program of study, usually at a community college. Research evidence (although nonexperimental) suggests strong positive impacts of

these programs on subsequent earnings (Reed et al., 2012). Apprenticeships also are popular in many European Union member states, as well as with foreign-based (especially German) companies opening plants in the United States (Schneider, 2013; Schwartz, 2013).

Finally, as discussed further below, a range of “career pathways” are being developed by states around the country. These are usually programs of occupational study in high schools and colleges that combine work experience and academic learning, with students earning a series of specific education credentials along the way. To date there exists no rigorous evaluation evidence as to their impacts on earnings over time. But broadly, work-based learning models that combine strong academic learning with paid work can help young adults attain both the postsecondary education and work experience needed by so many young people today.

HEALTH AND SOCIAL CAUSES AND CONSEQUENCES

Education and Health in the Short and Long Terms

As demonstrated by the evidence reviewed thus far on the long-term economic benefits of educational attainment, the high stakes of young adulthood discussed throughout this report are clearly evident in the educational system. Those high stakes are not strictly economic, as an educational gradient is seen in many other domains of functioning. For example, persistent educational disparities in health are well documented (Baker et al., 2011; Mirowsky and Ross, 2003). In short, more-educated Americans tend to experience significantly less morbidity and fewer functional limitations than their less-educated counterparts, and they report better levels of health overall. Perhaps most strikingly, they have substantially longer life expectancy. These disparities by level of education—typified by comparisons between 4-year college graduates and those who have not entered or graduated from such colleges—tend to become more pronounced across the life course, and on a population level have become more pronounced over time. Of course, some portion of these observed effects of educational attainment on health, including mortality, simply reflects selection effects—preexisting differences in who obtains a college degree and who does not—but not all of it does. Completing higher education—and obtaining more education in general—does appear to support and enhance health (Lauderdale, 2001; Lynch, 2003).

Why might going to college and obtaining more education lead to better health across the life course? Sociologists Mirowsky and Ross (2003) offer some general explanations. First, education leads to greater job stability, higher earnings, and access to work with better benefits, all of which support health and the avoidance of health problems. Second, education

cultivates the development of psychological resources, including feelings of personal control and analytical skills that enable people to better manage their health and make more informed health decisions, as well as networks of social support that protect people from health risks and stressors. Third, reflecting the first two mechanisms, education tends to facilitate healthier lifestyles, so that the behavioral profiles of more-educated individuals keep them in good health for longer periods of time. For example, college graduates are more likely to exercise and eat nutritiously, and consequently are less likely to be obese (see Yu, 2012). Similar trends extend to mental health, with lower depression and higher life satisfaction being seen among the more educated (Mirowsky and Ross, 2003). The correlation between education and health may not be completely causal, although no doubt part of it is. There are also other associations between education and long-term health. For example, those with lower educational attainment also had more adverse childhoods; this childhood experience leads to an increased stress response (allostatic load), which leads in turn to long-term health problems (Shonkoff et al., 2012).

The large literature on this subject suggests that education and health are positively related over the long run such that the more educated a young adult becomes, the healthier she or he will be in later life. Yet these long-term patterns may also subsume shorter-term risks associated with obtaining more education. In particular, attending college can be associated with poorer health behaviors relative to individuals of the same age who do not go to college. In recent years, for example, college students have used illicit drugs at slightly higher rates than their noncollege age-mates; in 2012, annual prevalence rates in these two groups were 37 percent and 35 percent, respectively, a disparity driven mainly by marijuana use but also capturing enrollment-related differences in amphetamine use (Johnston et al., 2013). This pattern does not extend to many of the more dangerous drugs, such as cocaine and heroin, nor does it apply to cigarette smoking (in 2012, 13 percent of college students were current smokers, compared with about 26 percent of noncollege young adults) (Johnston et al., 2013). Still, given the consistency of the link between educational attainment and health across the life course, these exceptions to the general rule during young adulthood are notable.

Perhaps no health risk among young adults on college campuses receives more attention than alcohol consumption. In 2012, more than two-thirds of college students (68 percent) reported drinking in the past month, compared with just over half (54 percent) of noncollege youth (Johnston et al., 2013). More troublesome is binge drinking (having five or more drinks on a single occasion in the past 2 weeks), which has for decades been consistently higher among college students than among their noncollege age-mates; in 2012, the respective rates were 37 percent and 30 percent

(Johnston et al., 2013). Drinking is widely viewed as a major part of college campus life in the United States, one that runs counter to the general pattern of higher education being conducive to health (Schulenberg and Maggs, 2002; Wechsler and Wuethrich, 2002). Evidence that the college years are a time of steady weight gain as well as a period in which many students have suicidal ideation also suggests that young adults on college campuses (and not just their peers who are not attending college) may need attention with respect to countering health risks (IOM and NRC, 2013; Nelson et al., 2007; Zagorsky and Smith, 2011).

Employment and Health in the Short and Long Terms

The employment and health outcomes of young adults are correlated, although the direction of causation is not always clear. Poor health appears clearly to generate low employment outcomes (Currie and Madrian, 1999). Whether low employment generally causes poor health, especially among young adults, is less clear. Very poor employment opportunities do appear to drive disconnected youth into crime and incarceration, as discussed below, and these outcomes are associated with poor long-term health outcomes, such as HIV infection (Johnson and Raphael, 2009). Research also has shown that sudden involuntary job loss can raise health and mortality risks, especially among older adults (Sullivan and von Wachter, 2009), although it is unclear whether this is true for more sporadic episodes of joblessness among young adults.

“It is very important for workplaces to have opportunities for guidance, professional and personal development, whether the young adult works as cashier or a manager.”

Another potential link between employment and health for young adults involves workplace safety. Young adults are a subset of the workforce with traits that create important requirements for safety, health, and well-being in the workplace. They have behavioral and cognitive attributes and less well-developed work skills, experience, and training that increase their risk for injury compared with older adults. Young adults’ vulnerability to occupational injury and illness also may result from their overestimation of their skill level; greater risk taking in their desire to meet their employer’s expectations; and greater tendencies to be distracted as a result of performing multiple activities, such as texting and driving motor vehicles, simultaneously. Shorter employment histories and fewer cumulative encounters with workplace safety training also tend to make young adults

less familiar with health and safety protections, such as state or federal occupational safety and health standards, hazard or injury reporting systems, and rights under workers’ compensation statutes in the event of on-the-job injury (CDC, 2013).

Data on nonfatal occupational injuries are provided by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics for young adults according to the age groups 16-19, 20-24, and 25-34. It is generally believed that these data understate the actual incidence of work-related injuries among young adults because of their reticence to report such injuries to their employer or their lack of awareness of reporting systems. Compared with older workers, young adult workers have higher nonfatal injury rates in the private sector but lower injury rates in the public sector, where work hazards differ (BLS, 2013). In 2012, nonfatal work injuries involving days away from work in private industry were 111 per 10,000 full-time workers for those aged 16-19, 109 per 10,000 full-time workers for those aged 20-24, and 100 per 10,000 full-time workers for those aged 25-34, compared with 102 per 10,000 full-time workers for all workers (BLS, 2013). Industries contributing the most to work injuries among young adults are the leisure and hospitality industry, the food and beverage industry, grocery stores, and the motor vehicle and parts industry. The major type of injury among young adult workers is musculoskeletal, particularly strains and sprains of tendons and ligaments (BLS, 2013). Cuts, lacerations, and burns are common injury types in the food preparation and restaurant industries. Data on injuries requiring emergency department (ED) visits, drawn from a surveillance sample of hospitals, have shown that work-related injuries are seen twice as often among workers under age 25 as among workers above this age, and that the leisure, hospitality, and retail industries account for slightly more than three-quarters of ED visits by young adult workers (CDC, 2013).

Compared with older workers, young adults have lower overall rates of fatal work injuries. Fatality rates for occupational injuries rise progressively from age 20 onward. In 2012, rates of fatal injuries were below 3.0 per 100,000 full-time equivalent workers among workers less than age 34 and above that level for all older age groups. Rates of fatal work injuries are higher for those aged 18-19 than for those aged 20-24 and 25-34, at 2.9, 2.4, and 2.4, respectively, per 100,000 full-time equivalent workers (BLS, 2014).

Fatal occupational injuries among young adults share some important epidemiological characteristics with those among older adults. Men are overwhelmingly affected compared with women, and the same events or exposures cause fatal work injuries in both young and older adults. Most work-related fatal injuries result from transportation collisions in mining, agriculture, and waste management, often with the young adult as driver; gun shootings and other assaults; being struck by objects or equipment; and falls from heights (BLS, 2014). The service and construction industries

account for the largest number of fatal injuries to young adults, but mining and agriculture have the highest rates of such injuries (BLS, 2014).

Disconnected Youth and Youth with Disabilities and Chronic Health Conditions

Given the important linkages among education, employment, and health and safety outcomes for young adults, the very weak education and employment outcomes of two groups raise particular concern: youth who are disconnected and those who have disabilities and chronic health conditions.

Disconnected Youth

As noted earlier, young adults who are out of school and out of work (or idle) for significant periods of time are often called disconnected youth.6 While disconnection can occur at any level of education, it is for those with no postsecondary credential that concern is highest.

The numbers of disconnected youth have almost certainly grown considerably since the beginning of the Great Recession. One very credible recent estimate puts the number at 6.7 million, which constitutes about 17 percent of the population aged 16-24 (Belfield and Levin, 2012). The rates are highest among African Americans and those aged 20-24, almost all of whom have left high school. About half of these youth, and no doubt even more among those who are high school dropouts rather than graduates, appear to be “chronically” disconnected and perhaps have never entered the formal labor market.

Many of these youth have low education (often no high school diploma) and poor basic skills. Disconnected youth also are likely to be scarred by their lack of work experience when they do try to enter the job market, in the form of either low employment rates or low wages (Belfield and Levin, 2012). Young women who are disconnected are frequently single mothers (and often became mothers as teens), while disconnected young men tend to be noncustodial fathers in one or more families.7 Disconnected young men, especially African Americans, also tend to have disproportionately high rates of incarceration and ex-offender status (Pager, 2003).

The combination of having a criminal record and a child support or-

__________________

6 They are also sometimes referred to as opportunity youth (see Chapter 1).

7 Despite the high correlations between teen motherhood (or unwed motherhood more generally) and poor education and employment outcomes, researchers continue to debate the extent to which the former causes the latter. See Hill et al. (2009), Kearney and Levine (2014), and Thomas (2012). The difficult experiences of young noncustodial fathers, especially in multiple families, are documented by Edin and Nelson (2013).

der can substantially reduce future employment prospects for these young men, even when they age out of crime. Employers tend to avoid hiring those with a criminal record (except in economic sectors where there is little contact with customers, children and the elderly, or cash), while those in arrears on their child support payments face high taxes in the form of wage garnishing and thus reduced incentives to work (Edelman et al., 2006; Holzer et al., 2004; Pager, 2003).

“I was released from the juvenile justice system in June 2012 and I applied to all these large stores, such as Sears and Home Depot, which you think would hire for the manpower. But I was denied. Most often when I got to the question of the criminal conviction, that’s what automatically changed the whole conversation.”

Any approach designed to help this population therefore requires policies that address a range of difficult personal circumstances and barriers, including low levels of education, basic skills, and work experience, along with the stigma and disincentives associated with a criminal record and child support debt.

Youth with Disabilities and Chronic Health Conditions

High school students receiving special education services (those identified as having a disability that interferes with their educational performance) do not do as well in school as the general population of high school students and are less likely to complete high school. Most youth with disabilities (72 percent) graduate from or complete certification for secondary school, but completion rates vary greatly with the type of disability (U.S. Department of Education, 2005). The highest rates of completion are among those with visual (95 percent) and hearing (90 percent) impairments, while the lowest rates are among those with emotional disturbance (56 percent). On average, students with disabilities who receive grades earn a lower grade point average and have much higher course failure rates than the general population of students (Newman et al., 2011a). The rate of ever failing a course in high school is highest among those with emotional disturbance (77 percent) and lowest among those with autism (27 percent). As in the general population, students with disabilities from households with lower incomes or of minority race have lower secondary school academic performance and attainment.

One study found that at ages 21-25, 60 percent of former special education students had had some postsecondary education, compared with 67 percent of their age-mates in the general population (Newman et al.,

2011b). Postsecondary school enrollment was highest among those with visual (71 percent) or hearing (75 percent) impairments and lowest among those with an intellectual disability (29 percent) (Newman et al., 2011b). Among those enrolling in postsecondary schooling, former special education students are twice as likely to enroll in 2-year colleges and almost twice as likely to complete that education compared with those in the general population. However, they are only half as likely to enroll in 4-year colleges and much less likely to complete 4-year college (34 percent versus 51 percent) compared with the general population (Newman et al., 2011b). Race or ethnicity and household income are not associated with different rates of postsecondary school enrollment or completion among former special education students. These findings highlight the central role of 2-year colleges for vulnerable young adults.

Not all students with disabilities or chronic health conditions are served in special education. Fewer than 10 percent of students with mental illness, for example, are enrolled in special education (Forness et al., 2012). Studies that reflect the broad spectrum of youth with mental illness confirm their low high school performance and completion rates (Davis and Vander Stoep, 1997). Epidemiological work suggests that these low rates of high school performance and attainment are due largely to the direct impact of childhood adversity and the presence of conduct and attention-deficit disorders (Breslau et al., 2011). Although colleges are seeing increased rates of students with mental health conditions on campus (Eisenberg et al., 2007), those with a mental illness that predates college entry are less likely to finish college than those without such a condition (Bachrach and Read, 2012; Kessler et al., 1995). Development of a mental health condition while in college also compromises school functioning and completion (Bachrach and Read, 2012). Other mental health issues, such as suicidal ideation or attempts, also are seen among college students. Survey results show that 1 in 10 college students contemplated suicide during the previous year, and 1-2 percent made an attempt (Brener et al., 1999; Kisch et al., 2005). One of the challenges faced by college students with mental illness is the particular social stigma of these conditions, which plays a role in reducing their willingness to request educational accommodations (Salzer et al., 2008) and to seek help for their condition (Eisenberg et al., 2007).

“My college work suffered due to mental health issues. My university didn’t understand what I was going through. I had to pay back $10,000 of scholarship money. They weren’t recognizing the mental health issue as an issue.”

Ongoing substance use in high school also contributes to educational difficulties—including dropping out of college—during the transition to adulthood (e.g., Patrick et al., 2013). Tobacco use during high school has stronger effects than alcohol and illegal drug use on school struggles (Breslau et al., 2011).

Employment rates at ages 21-25 are comparable among former special education students and their age-mates in the general population (Newman et al., 2011b). However, employment rates among those with learning disabilities or speech/language disabilities are more than 20 points higher than among those with deafness/blindness, orthopedic impairments, autism, multiple disabilities, or mental retardation. Those in the latter disability categories also are more likely to work part time than those in the former categories. It is notable that those with hearing impairments are among former special education students with the highest educational attainment, yet the lowest employment rates. Hourly wages among those who are employed are lower among former special education students than among their age-mates in the general population (Newman et al., 2011b). These findings indicate that for many students, special education services help them achieve employment on par with their same-age peers in the general population. However, numerous subgroups experience employment and income disparities.

Twelve percent of individuals under age 65 receiving Supplemental Security Income (SSI) are young adults aged 18-25 (Social Security Administration, 2012). Receiving these benefits is a strong deterrent to work (e.g., Bond et al., 2007; Burns et al., 2007; Frey et al., 2011). Further, despite some encouraging findings among former special education students described above, studies of employment among young adults with disabilities reveal that many challenges remain for this population. Major barriers to accessing good and satisfying employment include (1) a lack of work experience and restricted aspirations, (2) sporadic patterns of early employment, (3) limited access to postsecondary education and training, and (4) discrimination and prejudice (Lindstrom et al., 2013).

EDUCATION AND EMPLOYMENT POLICY FOR YOUNG ADULTS

The United States currently has a wide array of policies designed to support higher education and workforce development services, for both young and older adults, at the federal, state, and local levels, as well as laws protecting those with disabilities. We first describe the current policy landscape, and then review what can be learned from the research and evaluation literature about the effectiveness of these policies and related programs.

Workforce Programs

The greatest single source of funding for workforce development programs in the United States is the Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act (WIOA), which succeeded earlier programs and is administered by the U.S. Department of Labor.8 Title I of WIOA distributes three primary funding streams—for adults, dislocated workers, and youth (up to age 21)—that are allocated by state and local workforce boards. It also funds the Job Corps, one of the original “War on Poverty” programs, which provides job training for youth in residential settings nationwide. Young adults can potentially participate in programs funded by any of these streams, depending on their exact ages and circumstances.

Other titles of WIOA fund adult basic education, the labor market information and job search assistance provided at the roughly 3,000 American Job Centers around the country (formerly known as “One Stop” offices), and other services and access to income support through unemployment insurance that are available at these centers. The workforce services provided to adults and youth at these centers include basic job matching and counseling or testing, with limited availability of vouchers for training that is mainly short term (Besharov and Cottingham, 2011).

It appears that authorized spending on WIOA will be about $6 billion (CBO, 2014), although the actual appropriated amount may be different. This funding has declined dramatically over time in real terms, especially relative to the size of the U.S. workforce or the economy. But workforce funds also are provided by the U.S. Departments of Education, Health and Human Services, and Agriculture through such programs as Vocational Rehabilitation, Temporary Assistance for Needy Families, the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, and a variety of block grant programs.

According to Government Accountability Office estimates (GAO, 2011), 47 such federal workforce programs were disbursing some $18 billion in funding as of 2010, although most of these programs are quite limited in size. Expenditures by these programs total 0.1 percent of national gross domestic product, which is a relatively small sum compared with similar expenditures in other industrial countries. Still, there is likely some scope for savings through consolidation and more effective operation of some of these programs.

At the state and local levels, workforce training and services are administered through WIOA funding and other sources. In recent years, most states have begun to design programs that link economic and workforce development to train workers for the states’ high-growth and high-wage

__________________

8 Earlier versions of this legislation included the Comprehensive Employment and Training Act, the Job Training Partnership Act, and the Workforce Investment Act.

industries, although data indicating just how far these programs have come are sparse (Choitz and Harmon, 2014). “Sectoral” efforts, in which providers of training work directly in partnership with employers or industry associations to train workers for existing jobs in high-growth or high-wage industries are beginning to play major roles, as are the “career pathway” models alluded to earlier (Choitz and Harmon, 2014; National Governors Association Center of Best Practices, 2012). Many localities also have developed such partnerships, with some scale (National Fund for Workforce Solutions, 2014).

Finally, a wide range of small programs and pilots have been developed over the years, often with a mix of public and foundation funding, to test a variety of approaches to workforce development. The many small grant programs administered in the past decade by the Bush and Obama administrations have helped support this trend.9

Disability Law and Programs

Two federal laws—the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA)10 and the Rehabilitation Act of 197311—and their amendments are designed to help individuals with disabilities participate fully in society, including employment and education. Both provide protection from disability-based discrimination and mandate that employers offer reasonable accommodations for employees or applicants with disabilities.

The ADA, a civil rights law, provides protection against discrimination in private, state, and local government employment. None of its elements or amendments are specific to young adults. It provides protections primarily when individuals seek them, such as in requesting reasonable accommodations in the workplace. Thus, for young adults to receive many of the ADA’s protections, they must know about the law and pursue their rights.

The protections under the Rehabilitation Act prohibit discrimination in federal agencies, federal employment, the employment of federal contractors, and programs receiving federal financial assistance. The Rehabilitation Act currently is contained within the WIOA, and funds services and programs that include state vocational rehabilitation services, supported employment, independent living, and programs in training and research. Several sections of the current Rehabilitation Act mandate that federal and

__________________

9 These competitive grant programs from the U.S. Department of Labor include the High Growth Job Training Initiative, the Workforce Innovation in Regional Economic Development grants, the Trade Adjustment Assistance Community College and Career Training grants, and the Workforce Innovation Funds.

10 Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990, Public Law 101-336, 101st Cong. (July 26, 1990).

11 Rehabilitation Act of 1973, Public Law 93-112, 93rd Cong. (September 26, 1973).

state vocational rehabilitation programs engage in activities that support the transition from school to work for individuals with disabilities. These mandates are designed to prevent interruptions in services after individuals leave secondary school, to ensure that secondary students covered by either the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act or the ADA are provided transition services, and that vocational rehabilitation agencies and institutions of higher education have interagency agreements (or other such mechanisms) outlining various aspects of coordination. The services provided by state vocational rehabilitation agencies to those aged 16-24 under these mandates are called transition-age youth services. About 8 percent of transition-age youth with disabilities apply for state vocational rehabilitation services, and 56 percent of them eventually receive those services (Honeycutt et al., 2013). Little research has examined the impact of state vocational rehabilitation transition services (Davis et al., 2013; Honeycutt et al., 2013).

Higher Education

Most public expenditures on higher education—which nationally total more than $160 billion per year—occur at the state level in the form of aid to state colleges and universities as well as community colleges that helps keep tuition well below cost (Barrow et al., 2013). Many analyses of these expenditures suggest that these programs are relatively regressive, with the largest benefits being gained by higher-income families that send their children primarily to the flagship schools in state college and university systems (Barrow et al., 2013; Hansen and Weisbrod, 1969; Johnson, 2005).

Various federal programs also make important contributions to higher education, both public and private. For example, the Pell grant program (part of the Higher Education Act) finances tuition payments for low-income youth and adults aimed at breaking the intergenerational cycle of poverty and socioeconomic disadvantage (reflecting the generational theme of this report). This program has expanded dramatically in recent years, and its expenditures now total roughly $35 billion (Crandall-Hollick, 2012; Dynarski and Scott-Clayton, 2013). Since many students go to college—especially 2-year and for-profit institutions—to obtain a vocational degree or certificate, the Pell grant has effectively become the largest financer of vocational training in the United States. The federal government also operates direct loan and work-study programs, as well as a range of federal tax credits for tuition payments (Dynarski and Scott-Clayton, 2013).

Although much vocational education occurs in colleges and is funded by U.S. Department of Education programs, a wide gulf remains between these colleges and the job centers funded by the U.S. Department of Labor

through the WIOA that provide workforce services in many localities. This gulf appears to be beginning to break down, however, with an increasing number of job centers being located on community college campuses and with representatives of colleges sitting on local workforce boards. But a good deal more needs to be done in this regard.

The transition from secondary to postsecondary education involves vast changes in disability policy and practice as students move from a system of entitlement (Individuals with Disabilities Education Act) to one of eligibility (GAO, 2009). Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act, the ADA, and their amendments provide guidelines regarding students with disabilities in colleges, but the main focus is on providing equal access and preventing discrimination rather than promoting student success in college (GAO, 2009). According to the ADA, any college that receives federal funding must provide equal access through the use of reasonable accommodations and auxiliary aids (e.g., sign language interpreters). One of the greatest changes from high school to college is that school districts are obligated to identify and serve students with disabilities in high school, whereas colleges have reduced obligations to provide the array of services and supports required of high schools for their students with disabilities. Essentially, responsibility shifts from the school to the student; students themselves must disclose their disability to access accommodations in college. The result is practices that vary greatly across colleges (Cory, 2011; GAO, 2009) and may impose a greater burden on those with stigmatized disabling conditions (e.g., Yang et al., 2013).