Key Findings

- Young adults are at elevated risk of morbidity and mortality in a surprising variety of ways compared with adolescents and older adults.

- Policies and programs aimed at reducing the incidence and prevalence of disease and injury among young adults can be improved by taking a developmental perspective.

- The differential effects of public health interventions on subpopulations of young adults have not been adequately explored. Efforts to address health inequities will have to account for the transitional experiences of young adults, given that the effects of interventions during this period of life are likely to last for several decades.

- Mobile digital media and social networking have the potential to play a pivotal role as vehicles for public health interventions, and research on the effectiveness of these technologies is a high priority.

- The most successful public health interventions for young adults have been those that involve comprehensive, multilevel strategies using ecological approaches in multiple channels and venues to influence changes at the individual, organizational, and societal levels that can be sustained over time.

- The heightened vulnerability of young adults to a variety of health and safety risks supports an extension of some protective health policies beyond the legal definition of adulthood.

- An effective approach to public health policy and practice focused on young adults requires better integration and coordination of federal and state public health programs and effective use of the preventive services component of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act.

When their health, safety, and well-being are viewed from a developmental life-course perspective, young adults are at elevated risk of morbidity and mortality in a surprising variety of ways compared with adolescents and older adults. What makes this surprising is that conventional wisdom suggests young adults ought to be in peak physical condition, given that they are beyond the pitfalls of adolescence and not yet experiencing the declines of aging. The vulnerability is even greater among those of lower socioeconomic position and from racial and ethnic minorities, who are exposed to greater risks and dangers than their more advantaged peers and lack safety nets to protect them (NIHCM, 2007). Policy makers and practitioners have recognized that the health, safety, and well-being of adolescents can be enhanced—during adolescence and thereafter—by basing policy and practice on an integrated understanding of this distinct period of development. A key conclusion of this report is that the health, safety, and well-being of young adults can similarly benefit from bringing a life-course perspective to bear on public health policies and programs and on the delivery of health care.

As chronic health conditions become the key health challenge for the 21st century, community-based prevention efforts will increasingly become an important focus for both the public health and health care delivery systems. It is important to recognize the mutually reinforcing connection between effective population-level and individual-level interventions. At the same time needs for treatment are reduced through prevention, public health activities can help increase the effectiveness of health interventions. In fact, Milstein and colleagues (2011) estimate that if protective public health interventions were integrated with coverage and care approaches, in 10 years they could save 90 percent more lives in the United States and in 25 years 140 percent more lives than could be saved through coverage and care approaches without such interventions (Milstein et al., 2011).

This chapter addresses policies and programs undertaken by the public health system (public agencies and their partners at the national, state, and community levels) aimed at reducing the incidence and prevalence of disease and injury among young adults. The next chapter addresses the

delivery of health care services for young adults, including both preventive services and treatment delivered by primary care physicians and other health care providers. The chapter begins with a brief overview of public health perspectives and activities. After highlighting the public health issues associated with young adulthood, we then review the literature on the effectiveness of public health initiatives, particularly those targeting health and safety problems with elevated prevalence among young adults, and summarize features of public health interventions that have been successful in reducing the risk of morbidity and mortality among young adults. Next we give special attention to the potentially pivotal role of mobile digital media and social networking as vehicles for public health interventions. We then turn to the role of public health policies, such as those related to the purchase of alcohol and tobacco, in protecting the health, safety, and well-being of young adults. In the next section, we look at the extent to which state and federal public health programs focus on those issues most salient to young adults, and on how these programs can be improved and better coordinated to best address these issues. The final section presents conclusions and recommendations.

OVERVIEW OF PUBLIC HEALTH PERSPECTIVES AND ACTIVITIES

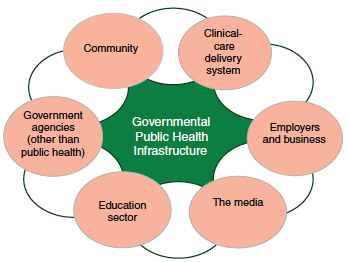

The mission of public health has been defined as “organized community efforts aimed at the prevention of disease and promotion of health. It links many disciplines and rests upon the scientific core of epidemiology” (IOM, 1988, p. 41). Figure 6-1 shows how the different sectors involved, while acting individually, also work together as a public health system in pursuing health goals. Moreover, contemporary public health activities are grounded in an ecological approach that takes account of cross-level influences on individual health behaviors and conditions, including the natural, social, and built environments and the contributions of other government agencies or sectors—such as transportation, environment, economic development, and education—that influence population health (IOM, 2011, 2012b; Sallis et al., 2008). Similarly, public health interventions encompass a wide array of policies and programs, ranging from tax policies to media campaigns.

Although broad action on multiple determinants involving diverse public and private actors is needed to achieve the greatest effects on population health, the governmental public health infrastructure serves an essential coordinating role and, in many contexts, service delivery and regulatory roles (IOM, 2011). In the context of ensuring the health, safety, and well-being of young adults, we focus here on the 10 essential activities of state and local public health agencies listed in Box 6-1, which have become widely accepted in the field (IOM, 2011).

FIGURE 6-1 The intersectoral public health system.

SOURCE: IOM, 2011.

BOX 6-1

10 Essential Public Health Services

- Monitor health status to identify and solve community health problems.

- Diagnose and investigate health problems and health hazards in the community.

- Inform, educate, and empower people about health issues.

- Mobilize community partnerships and action to identify and solve health problems.

- Develop policies and plans that support individual and community health efforts.

- Enforce laws and regulations that protect health and ensure safety.

- Link people to needed personal health services and ensure the provision of health care when otherwise unavailable.

- Ensure a competent public and personal health care workforce.

- Evaluate the effectiveness, accessibility, and quality of personal and population-based health services.

- Conduct research to attain new insights and innovative solutions to health problems.

SOURCE: IOM, 2011.

The leadership role of public health agencies should not be regarded as synonymous with a directive role. When public health was focused primarily on infectious disease control, its activities often were based on coercive legal authority. However, as the scope of public health has broadened to include preventing chronic disease, promoting healthy communities, and reducing or even eliminating health disparities, collaborative and facilitative approaches have become predominant. Greater attention is being paid to mobilizing and engaging important stakeholders, including community-based organizations, in promoting public health. This multisectoral approach is based on the premise that local agencies and organizations have a better understanding of the local context in which public problems can be studied and solutions can be developed, executed, and sustained (Israel et al., 2008; Minkler and Wallerstein, 2008; Ramanadhan et al., 2012).

It must be noted that the list of essential public health services today would also include ensuring equity within and across different population groups. Despite tremendous investments in research, planning, and deployment of public health strategies and their success, it has become clear that the benefits of these programs are accruing unequally across socioeconomic and racial/ethnic groups (Spalter-Roth et al., 2005). The challenge of erasing persistent health disparities has been the subject of extensive attention in recent years (IOM, 2002, 2012c), and the contributing social and individual factors are now better understood. These factors—which include social class, race and ethnicity, social and economic policies, racism, geography, housing, and communication inequalities, among many others—appear to explain why certain groups experience greater adversity due to risk conditions and also are often unable to take advantage of programs and policies that should ameliorate such conditions (IOM, 2011). A great deal of this work has focused on either childhood poverty or the experience of adults, with much less attention to young adults. But it is clear that any efforts to address health disparities will have to account for the experience of this important age group, as the effects they experience are likely to last for several decades.

PRIORITY PUBLIC HEALTH ISSUES FOR YOUNG ADULTS

Some recent reviews of young adult health have pointed to encouraging trends, such as decreases in rates of suicide, gonorrhea, and cigarette use1 (Mulye et al., 2009; Park et al., 2006, 2014). However, the mortality rate for young adults aged 20-24 is 93.5 per 100,000, compared with

__________________

1 Although use of cigarettes is declining, the use of other tobacco products, such as electronic cigarettes, may be increasing (King et al., 2013).

60.8 among older adolescents (aged 15-19) and 17.4 among younger adolescents (aged 10-14), showing a substantial increase with age (CDC, 2014a). Young adults are at greater risk for short- and long-term impacts on health and have worse health outcomes than adolescents in many areas (Park et al., 2014). Overall, as compared with other age groups, young adults have the highest rate of death and injury from motor vehicles, homicides, mental health problems, sexually transmitted infections (STIs), and substance abuse (Neinstein, 2013). Yet in general, most of the leading causes of illness and death among young adults are largely preventable (Mulye et al., 2009).

Important developmental changes occurring during young adulthood can promote or compromise health and well-being (Harris et al., 2006; Mulye et al., 2009; Neinstein, 2013). Most young adults are transitioning from direct parental supervision to living on their own, which can create a period of vulnerability to unsafe and unhealthy behaviors. Many young adults need help coping with stressful circumstances in school or on the job, and a significant subset are at risk of experiencing acute emotional distress and the onset of major mental disorders (Garcia, 2010). These conditions can, in turn, impact education and workplace achievement in the short term as well as throughout life. There are also profound health and well-being consequences for young adults who have children (as discussed in Chapter 3). Moroever, risk-taking behaviors associated with morbidity and mortality across the life span tend to emerge or peak during young adulthood, with important immediate and long-term health consequences (Park et al., 2006, 2014). For example, use of tobacco and low levels of fitness and poor nutrition increase the probability of developing diseases such as cardiovascular and pulmonary disease and cancer later in life (Santelli et al., 2013). The collective impact of these problems is noticeable at the public health level, where little change in risky behavior has occurred over the past decade. And while in some ways, young adults appear relatively healthy, many public health concerns for young adults remain inadequately and ineffectively unaddressed (Park et al., 2006, 2014).

“Many people think, ‘you just have the blues, and you will get over it.’ Many people don’t recognize the long-term effects in terms of employment, general quality of life, et cetera.”*

For the past 30 years, Healthy People has set the national objectives for improving public health. Healthy People 2020 focuses more on adolescents and young adults as compared with previous decades (Koh et al.,

__________________

* Quotations are from members of the young adult advisory group during their discussions with the committee.

2011). Based on guidance from national experts, Healthy People 2020 identifies 41 “core indicators for adolescent and young adult health,” which concentrate on individual outcomes, as well as systems that influence health for these populations.2 The indicators span seven domains: health care (health insurance coverage, well care, immunizations), healthy development (adult connection, graduation, sleep, transition planning3), injury/violence prevention (motor vehicle crashes, riding with a drinking driver, graduated driver licensing laws, homicide, exposure to violence, physical fighting), mental health (suicide rate and attempts, depression, treatment), substance abuse (marijuana use, binge drinking, treatment), sexual and reproductive health (pregnancy prevention, STIs, HIV, reproductive health services), and prevention of chronic disease (oral health, hearing, obesity, physical activity, tobacco) (HHS, 2012a). Although all of the indicators are important for the health, safety, and well-being of young adults, this chapter focuses on an illustrative selection of public health challenges that are related most specifically to the health, safety, and long-term well-being of young adults and that pose substantial public health burdens—motor vehicle injuries; homicide and nonfatal assaultive injuries; sexual assault and intimate partner violence; mental health disorders and suicide; substance abuse; sexual and reproductive health; and chronic disease prevention, including decreasing obesity, reducing tobacco use, and increasing immunizations. Box 6-2 presents key findings on the public health challenges for young adults.

In addition, race, ethnicity, sex, sexual identity, age, disability, education, socioeconomic position, and geographic location all are associated with the health and safety of young adults (Mulye et al., 2009). Among both adolescents and young adults, certain populations have higher rates of risky behaviors, such as unhealthy eating, lack of physical activity, unprotected sexual activity, substance use, and unsafe driving (Park et al., 2014). Some examples are presented in Box 6-3. Major gender differences exist, as well as considerable ethnic and racial disparities, with non-Hispanic black and American Indian/Alaska Native young adults faring worse in many areas (Park et al., 2014). As Box 6-3 shows, many statistics are worse for certain populations than for others, but it is important to note that the differences go both ways. For instance, black males have a higher homicide rate than white males in this age group (100.3 versus 11.4 homicides per 100,000), but the reverse is true for the use of marijuana between early adolescence and young adulthood (Chen and Jacobson, 2012; Smith and Cooper, 2013).

__________________

2 See http://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/learn/Draft_Core_Indicators_Web.pdf (accessed October 22, 2014) for a full list of indicators.

3 Transition planning refers to individuals with special health care needs whose health care provider has discussed transition planning from pediatric to adult health care.

BOX 6-2

Illustrative Public Health Challenges for Young Adults

Below are some of the public health challenges that impose the greatest burdens on the health, safety, and well-being of young adults. They are presented using the Healthy People 2020 adolescent and young adult domains as a guide.

Injury and Violence Prevention

Reducing Motor Vehicle Injuries

- Motor vehicle crashes account for the largest percentage (approximately 20 per 100,000) of unintentional injury fatalities for 18- to 25-year-olds in the United States (Neinstein, 2013).

- Nonfatal injury rates also are higher among 18- to 25-year-olds than among 12- to 17-year-olds and 26- to 34-year-olds (Neinstein, 2013).

- In 2010, motor vehicle–related hospitalization and treatment of young adults in emergency departments cost the health care system $9 billion (Neinstein, 2013).

- In 2012, 32 percent of 21- to 24-year-olds involved in fatal motor vehicle crashes had blood alcohol levels of .08 or higher, followed by those aged 25-34 (29 percent) (versus 18 percent for those aged 16-20) (NHTSA, 2013).

- Drivers in their 20s accounted for 23 percent of drivers involved in fatal crashes and 27 percent of distracted driving fatalities, 34 percent of which involved use of cell phones (NHTSA, 2014).

Reducing Homicide

- Homicide is the second leading cause of mortality for 18- to 25-year-olds (Neinstein, 2013).

- Young adults aged 18-24 had the highest homicide rate of any age group but also experienced the greatest rate (22 percent) of decline from 2002 (15.2 per 100,000) to 2011 (11.9 per 100,000) (Smith and Cooper, 2013).

- Between 1981 and 2010, firearms accounted for nearly 80 percent of all homicides among 10- to 24-year-olds, and on average, firearms homicides occurred at 3.7 times the annual rate of nonfirearms homicides (CDC, 2013b).

Reducing Nonfatal Assault

- Males aged 18-25 are 70 percent more likely to be assaulted than 12- to 17-year-old males and 50 percent more likely than 26- to 34-year-old males (Neinstein, 2013).

- Young adults aged 18-25 are 220 percent more likely than 12- to 17-year-olds and 75 percent more likely than 26- to 34-year-olds to be injured by firearms (Neinstein, 2013).

- In 2011, more than 700,000 10- to 24-year-olds were treated in emergency departments for physical assault injuries (CDC, 2012).

- In 2011, the nonfatal assault-related injury rate was highest for those aged 20-24, with a rate of 1,867.5 per 100,000 for males and 1,215.1 per 100,000 for females (CDC, 2013d).

Reducing Sexual Assault and Intimate Partner Violencea

- Females aged 18-34 are more likely to experience sexual violence (about 4 victimizations per 1,000) than 35- to 64-year-olds (approximately 1.5 per 1,000) (Planty et al., 2013).

- Between 2004 and 2006, more than 100,000 females and 3,500 males aged 10-24 received emergency medical care for nonfatal sexual assault injuries (Gavin et al., 2009).

- The majority of female victims (79.6 percent) experienced their first completed rape before age 25—42.2 percent before age 18 (Black et al., 2011).

- In a study of undergraduate females, almost 20 percent reported experiencing completed sexual assault since entering college (Krebs et al., 2009).

- Almost one-third of female veterans were raped or sexually assaulted while serving in the military (Natelson, 2009), and in fiscal year 2013, among the 3,337 sexual assault investigations in the military, 65 percent of victims were under 25 (DoD, 2014).

- Intimate partner rape, physical violence, and/or stalking has been experienced by 35.6 percent of women and 28.5 percent of men (Black et al., 2011).

- Almost half of women (47.1 percent) and 38.6 percent of men who ever experienced intimate partner rape, physical violence, and/or stalking were aged 18-24 (Black et al., 2011).

- Intimate partner violence can lead to negative physical and mental health outcomes, ranging from gastrointestinal problems, migraines, and depression to posttraumatic stress disorder and suicidal thoughts and behavior (Randle and Graham, 2011; Stewart and Robinson, 1998).

Mental Health Conditions

Preventing Mental Health Disorders

- Approximately 75 percent of lifelong mental health disorders are manifest by age 24 (Kessler et al., 2005), and many conditions, such as depression, anxiety disorders, psychoses, and eating and personality disorders, start before age 24 and persist into adulthood (IOM and NRC, 2013; Patel et al., 2007; Paus et al., 2008).

- Data from the National Study of Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) from 2010 to 2012 indicate that 18.7 percent of 18- to 25-year-olds had had any mental illness in the past year, and 3.9 percent had had a serious mental illness (SAMHSA, 2014). In the past year, among those with any mental illness, 66.6 percent had not received mental health services, and 47 percent with a serious mental illness had not received treatment (SAMHSA, 2014).

Preventing Suicide

- Suicide is the third leading cause of mortality in young adults aged 18-25 (Neinstein, 2013).

- Current young adult suicide rates are almost twice as high as those for adolescents (CDC, 2014d).

Substance Abuse

Reducing Substance Use Disorders

- Compared with adolescents, young adults have a higher rate of drug-related causes of death: 16.7 percent of all deaths among 20- to 29-year-olds have drug-related causes versus 2.2 percent among 10- to 19-year-olds (Mack, 2013).

- NSDUH data from 2012 indicate that 18.9 percent of young adults had substance dependence or abuse disorders, a rate markedly higher than that among 12- to 17-year-olds (6.1 percent) and adults 26 and over (7.0 percent) (SAMHSA, 2013).

- From adolescence to young adulthood, alcohol use increases fourfold, binge drinking (five or more alcoholic drinks on a single occasion in the past 2 weeks) fivefold, and heavy alcohol use (five or more binge drinking episodes in the past month) 10fold (SAMHSA, 2013).

- Among 16- to 34-year-olds, 21- to 25-year-olds are most likely to drive under the influence of alcohol (Neinstein, 2013).

- In 2012, 39.5 percent of 18- to 25-year-olds participated in binge drinking and 12.7 percent in heavy drinking, rates similar to those in 2011 (39.8 percent and 12.1 percent, respectively) (SAMHSA, 2013).

- Among young adults aged 18-22, full-time college students have higher binge drinking rates than non-full-time students (Neinstein, 2013).

- Rates of past-month marijuana use double from adolescence (7.6 percent) to young adulthood (18.8 percent); after age 26, rates of use drop to approximately 5 percent (SAMHSA, 2012).

- About 1.1 percent of 18- to 25-year-olds reported using cocaine in the past month, which is similar to the rate for hallucinogens (SAMHSA, 2013).

- Young adults aged 18-25 have the highest rates of abuse of prescription opioid pain relievers, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder stimulants, and antianxiety drugs (NIH, 2014).

- Approximately 3,000 young adults died from prescription drug (mainly opioid) overdoses in 2010, which is more than the number who died from heroin and cocaine overdoses; many more needed emergency treatment (NIH, 2014).

Sexual and Reproductive Health

Reducing Unintended Pregnancies and Promoting Healthy Birth Spacing

- In 2012, the mean age of mother at first birth was 25.8, an increase from 25.6 in 2011 and from 21.4 in 1970 (Martin et al., 2013).

- The highest rates of unintended pregnancy occur in 20- to 24-year-olds (50 percent, compared with 25 percent in 25- to 44-year-olds) (Mosher et al., 2012; Neinstein, 2013). This means that about 2.6 million births between 2002 and 2006 among 20- to 24-year-olds were unintended, and these percentages have remained relatively steady since 2002 (Mosher et al., 2012).

- The percentage of unintended pregnancies ending in abortion is 37 percent among 15- to 19-year-olds and 41 percent among 20- to 24-year-olds (Neinstein, 2013).

Sexually Transmitted Infections (STIs)/HIV Prevention

- The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimates that almost 20 millionb new STIs occur yearly in the United States; 15- to 24-year-olds account for 50 percent of all new STIs, although they represent just 25 percent of the sexually experienced population (CDC, 2013c).

- Cervical and human papillomavirus (HPV) infections are the most common STIs, with 74 percent of new infections (6.2 million) each year occurring in 15- to 24-year-olds (Neinstein, 2013).

- Between 2008 and 2010, HIV rates increased (CDC, 2013e), with the highest rate of new cases occurring in 20- to 24-year-olds.

Preventing Chronic Diseases

Decreasing Obesity

- Overweight and obesity rates increase from adolescence to young adulthood. Rates are almost 50 percent in male and female 18- to 25-year-olds and are nearly 60 percent in female and more than 70 percent in male 26- to 34-year-olds (Neinstein, 2013).

- Even though young adults are doing better at meeting the recommended physical activity guidelines, about 40 percent still do not do so (Neinstein, 2013).

- In the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, males aged 18-24 reported about 5.4 hours a day of sedentary activity versus 7.4 hours for 12- to 17-year-old males; the corresponding figures for females were 5.7 and 8.0 hours (Neinstein, 2013).

Reducing Tobacco Use

- Approximately 90 percent of smokers start smoking by age 18, and 99 percent start by age 26 (HHS, 2012b).

- Of all age groups, young adults have the highest rate of current cigarette smoking, with approximately one of every three young adults under 26 being a smoker (HHS, 2012b).

- Among 18- to 22-year-olds, 21.3 percent of full-time college students reported smoking cigarettes in the NSDUH, compared with 37.2 percent among those not enrolled in college full time (SAMHSA, 2013).

- In 2012, among 18- to 25-year-olds, 10.7 percent had smoked cigars and 5.5 percent had used smokeless tobacco (the highest prevalence of any age group) in the past month (SAMHSA, 2013).

Increasing Immunizations

- Currently, 30 percent of 19- to 26-year-old females, 2.8 percent of 19- to 21-year-old males, and 1.7 percent of 22- to 26-year-old males are initiating HPV vaccination (Kester et al., 2014).

- In 2010, 25 percent of 18- to 25-year-olds received the influenza vaccine, versus 31 percent of 26- to 34-year-olds, and only 12-16 percent of 18- to 25-year-olds received the pertussis vaccinec (Neinstein, 2013).

________________

a Intimate partner violence, as defined by the National Crime Victimization Survey, includes rape or sexual assault, robbery, aggravated assault, and simple assault committed by the victim’s current or former spouse, boyfriend, or girlfriend (Catalano, 2013).

b This estimate is based on eight common STIs: chlamydia, gonorrhea, hepatitis B virus, herpes simplex virus type 2, HIV, human papillomavirus, syphilis, and trichomoniasis.

c The pertussis vaccine prevents against a respiratory disease, commonly known as “whooping cough,” that is highly contagious.

BOX 6-3

Illustrative Health Disparities

Below are some of the public health disparities (presented in alphabetical order) that impact the health, safety, and well-being of young adults.

Chronic Disease Prevention

- Among females over 18, the overall prevalence of obesity in 1999-2010 was 51 percent among non-Hispanic blacks, compared with 41 percent among Mexican Americans and 31 percent among non-Hispanic whites (May et al., 2013).

Homicide

- The peak rate of homicide victimization for black males occurs at the age of 23 (100.3 homicides per 100,000 population). This is almost 9 times higher than the peak rate for white males, which occurs at the age of 20 (11.4 homicides per 100,000 population) (Smith and Cooper, 2013).

- Homicide rates among black females peak at age 22 (11.8 homicides per 100,000), compared with white females, whose homicide rate is highest before the age of 2 (4.5 per 100,000) (Smith and Cooper, 2013).

Immunizations

- In females aged 18-26, there were significant increases in uptake of HPV vaccination (≥1 dose) from 2008 to 2012 (11.6 to 34.1 percent). However,

Hispanics and women with limited access to care continued to have lower rates of vaccination (Schmidt and Parsons, 2014).

Intimate Partner Violence

- The rate of intimate partner violence for females of all ages (5.9 per 1,000) is nearly six times that for men of all ages (1.1 per 1,000) (Catalano, 2013).

Mental Health Conditions

- Studies have found that 15- to 24-year-old males are more reluctant to try to find professional care for mental health problems than their female counterparts, and young indigenous and ethnic minorities may be even less likely to do so than whites (Rickwood et al., 2007). Black young adults aged 18-26 are less likely than other racial/ethnic groups to receive mental health services (Broman, 2012).

- A study of 21- to 25-year-olds found that rates of mental disorders and suicidal behavior among those with a predominantly homosexual orientation were 1.5 to 12 times higher than the rates among those with an exclusively heterosexual orientation (Fergusson et al., 2005).

Motor Vehicle Injuries

- Among 20- to 24-year-olds, rates of mortality due to motor vehicle crashes are significantly higher for males (25.8 per 100,000 population) than for females (4.2 per 100,000). The highest rates are among African American males (106.1), followed by non-Hispanic American Indian/Alaska Native males (20.6 per 100,000) (CDC, 2014a).a

Nonfatal Assault

- Males aged 18-25 are more than 8 times as likely as their female counterparts to be nonfatally shot (Neinstein, 2013).

- In 2012, among 20- to 24-year-olds, the unadjusted violent victimization rate was 100.6 per 1,000 for persons with disabilities and 36.6 for those without disabilities (Harrell, 2014).

- In 2012, 35.8 percent of overall hate violence survivors and victims were aged 19-29, a slight increase from 2011 (33 percent) (NCAVP, 2013).

Reproductive Health

- In 2012, among unmarried females aged 20-24, birth rates were highest among African Americans (103.5 per 1,000) and Hispanics (96.5 per 1,000), while the birth rate for non-Hispanic whites of the same age was 46.6 per 1,000 (Martin et al., 2013).

Sexual Assault

- Among 18- to 25-year-olds, females are 18 times more likely to be sexually assaulted than males (Neinstein, 2013).

- Among 12- to 34-year-olds, African Americans have the highest rates of sexual assault; among 18- to 25-year-olds, they are 63 percent more likely than whites and 216 percent more likely than Hispanics to be sexually assaulted (Neinstein, 2013).

Sexually Transmitted Infections (STIs)/HIV Prevention

- The rate of HIV diagnosis per 100,000 African American 20- to 24-year-olds (146.9) is more than 4 times the rate for Hispanics (33.3) and almost 12 times that for whites (12.3) in the same age group (CDC, 2013e).

- Among all gay and bisexual males aged 13-24, there was an increase of 22 percent in the incidence of HIV infection from 2008 to 2010 (7,200 to 8,800). The highest incidence within this age group was among African American males, accounting for 4,800 cases (CDC, 2012).

Substance Use

- Past-month alcohol use rates are similar among females (58 percent) and males (63 percent) aged 18-25, with the highest rates being among whites (67 percent) and Hispanics (54 percent) and the lowest among Native Hawaiians/Other Pacific Islanders (43 percent). Binge drinking is higher among males (46 percent) than females (33 percent) of the same age group, and lowest among African Americans (27 percent) and highest among whites (46 percent) and non-Hispanic Native Americans/Alaska Natives (41 percent) (SAMSHA, 2013).

- Past-month marijuana use is higher among males (23 percent) than females (14 percent) aged 18-25, with the highest rates being among African Americans (22 percent) and whites (20 percent), followed by Native Americans/Alaska Natives (16 percent) (SAMSHA, 2013).

- Between early/middle adolescence and young adulthood, whites generally exhibit the highest levels of alcohol use and heavy drinking, while African Americans exhibit the lowest levels, although levels of alcohol use and heavy drinking do not show significant variation across different racial and ethnic groups after age 30 (Chen and Jacobson, 2012).

PUBLIC HEALTH INTERVENTIONS FOR YOUNG ADULTS

Public health interventions include a broad array of activities, such as informing or educating the targeted population about risks, persuading them to reduce risk, creating incentives or disincentives to encourage them to adopt healthy or safe behaviors, and modifying the environment to reduce exposure to risks or to promote or facilitate safe or healthy behaviors. Exposures include not only environmental toxins and dangerous products but also adverse social experiences, such as racism, violence, and social threats or health risks resulting from poor living and working con-

- Even though their levels of marijuana use start to decline after age 29, African Americans have the highest rates of marijuana use after their late 20s compared with whites, Hispanics, and Asians (Chen and Jacobson, 2012).

Suicide

- In the 18-25 age group, non-Hispanic blacks are 1.3 times, Asians 1.7 times, Native Americans/Alaska Natives 1.6 times, and Native Hawaiians/Other Pacific Islanders 7.1 times more likely to have suicidal ideation than whites (Han et al., 2014).

- Among those aged 20-24, suicide is approximately three times higher in males (13.8 per 10,000) than in females (4.7 per 10,000) (CDC, 2014a).

- High school graduates aged 18-25 are 1.3 times more likely than college graduates to have suicidal ideation; unemployment also is associated with a higher risk of suicidal ideation in 18- to 25-year-olds (Han et al., 2014).

- The lifetime prevalence of suicide attempts in gay and bisexual male adolescents and adults was four times that in comparable heterosexual males, and the prevalence among lesbian and bisexual females was almost twice that among heterosexual females. This is the opposite of the gender pattern found in the general population (HHS, 2012c; King et al., 2008).

Tobacco Use

- Past-month cigarette use rates among 18- to 25-year-olds are highest among non-Hispanic Native Americans/Alaska Natives (62 percent), followed by whites (44 percent) and African Americans (32 percent); the rates are lowest among Asians (19 percent) (SAMSHA, 2013).

- Cigarette use is highest for whites through adolescence and young adulthood, while use among African Americans is higher after age 30 than for other racial and ethnic groups (Chen and Jacobson, 2012).

________________

a These rates do not include those classified as “undetermined intent.” If those are added, the rates rise to 42 per 100,000 for males and 13.7 for females, and the highest rate is 58.2 for American Indian/Alaska Native males.

ditions. To the extent that individual behaviors play a causal role, recent public health approaches go beyond changing those behaviors to focus on mobilizing and engaging different sectors to create an environment that facilitates and sustains behavior change, as well as on changing public health practice and policies. These interventions can target the whole population of a community or specific subpopulations thought to be at elevated risk. They can be deployed separately or used in combination, creating synergy. Tools may also include legal requirements or prohibitions. All of these approaches have been used, with varying degrees of success, to address the

significant problems identified above that threaten the health, safety, and well-being of young adults, although previously, the focus was primarily on changing individual behavior rather than altering the broader context and environment.

When a multilayer approach is implemented—for example, to reduce the incidence of unsafe driving due to either alcohol use or distracted driving—the likelihood of success is greater (Park et al., 2006). The ecological model or approach assumes that individual behaviors are products of influence at multiple levels, including intrapersonal, interpersonal, organizational, community/built environment, and public policy (Bronfenbrenner, 1979; Sallis et al., 2008). Moreover, a critical assumption is that behaviors are outcomes stemming from interactions across levels and that the context in which behaviors occur can exert significant influence on individuals (Bronfenbrenner, 1979; Sallis et al., 2008). With respect to risky behaviors, for instance, young adults working in the construction industry are likely to be socialized to a different set of norms and practices than those attending 4-year colleges. As an example, the greater use of tobacco among blue-collar workers may be attributable to a lack of knowledge and social supports at the individual level and perhaps to fewer restrictions on smoking in the workplace (Sorensen et al., 2004). Ecological approaches draw on a variety of theories and are robust when applied to specific behaviors. While these approaches have been used for some time, rigorous research has just begun to explore the mechanisms explaining the outcomes of multilevel interventions. In this section, we summarize the evidence base on public health interventions in selected priority areas to illustrate what is known.

Goals of Public Health Interventions

Promoting change in public health is a complex endeavor in terms of both the outcomes expected to result from a campaign and the context in which campaign messages are disseminated and received (Randolph and Viswanath, 2004). Health outcomes vary considerably, including changes in cognition, attitudes, beliefs, affect, salience, preferences, behavioral intentions, and behaviors at the individual level. A campaign may focus on the initiation of new behaviors, such as beginning to eat healthfully or engaging in physical activity (Snyder et al., 2004). In the case of risky behaviors, such as unsafe sex and use of tobacco, alcohol, or illicit drugs, one goal is to deter initiation, but a second stage can be directed at those who may not have been deterred or preventing relapse in the case of tobacco or drug use. Other campaigns may reinforce positive health messages, promoting maintenance, whether of healthy eating or physical activity (Atkin and Rice, 2012). The temporality of campaign effects is another critical consideration, ranging from short-term effects (e.g., influenza vaccination) to longer-term

effects, such as maintaining healthy lifestyles in youth, the effects of which may last well into adulthood (Marcus et al., 2006). The idea of deferring immediate rewards to reap future well-being, such as by stopping smoking in youth to protect oneself from cardiovascular diseases or cancer in adulthood, is a challenging message to communicate, particularly to adolescents and young adults (Hoek et al., 2013). Finally, aside from the effects of an intervention on individual behavior, public health campaigns may aim to shape social norms and to promote, advocate, and instill changes at the institutional and community levels (Holder and Treno, 1997; Hornik, 2002; Hornik and Yanovitzky, 2003; Viswanath and Finnegan, 2002).

In the following sections, we briefly review public health campaigns and other interventions in some of the priority areas discussed earlier.4 We then offer a distillation of lessons learned from these campaigns.

Tobacco Use

Using tobacco can cause cancer and heart and lung disease and can affect fetal well-being (Viswanath et al., 2010b). Tobacco use is estimated to cost 480,000 lives per year as a result of cancer in at least 18 different organ sites and other chronic diseases, such as cardiovascular and chronic obstructive pulmonary diseases (HHS, 2014c; Viswanath et al., 2010b), yet it is one of the most preventable causes of mortality and disease in the United States. Not surprisingly, public health interventions attempting to dissuade people from initiating tobacco use, as well as promoting cessation among users, have received considerable attention.

Tobacco control interventions are an outstanding example of multilevel approaches whereby interventions at one level have been aided by interventions at other levels (NCI, 2008). At the societal and community levels,

__________________

4 To review the interventions focused on young adults that are discussed, we conducted an extensive search of the literature using PubMed and a number of search terms derived from the priority areas specified in Chapter 5, including the combined terms “young adult,” and “intervention.” Additional search terms included “African American,” “Latino,” and “low income” to capture a more diverse sample. A secondary search was conducted using “young adult” and “intervention” in the Cochrane Review Database. Searches were restricted to articles published between 2009 and 2014, although reviews that included individual articles before this date were included. Other inclusion criteria were (1) reported findings of an intervention (those reporting only protocols or cost analyses were excluded); (2) inclusion of samples of healthy individuals that were not pregnant or diagnosed with cancer, diabetes, or another chronic condition; and (3) inclusion of samples of young adults aged 18-25 (articles including ages above or below this range were considered only if they were review articles or studies in which the mean age was within this range). The search was not exhaustive; reference lists were not searched for other relevant articles, and other search terms could have been used to identify additional articles. Priority was given to articles that were systematic reviews or emphasized population-level strategies.

evidence shows that comprehensive tobacco control programs, including tax increases, public smoking bans, media campaigns, youth access restrictions, and cessation programs, have reduced the prevalence and intensity of tobacco use (HHS, 2012b; IOM, 2007). At the individual level, media campaigns have focused on promoting knowledge of risks resulting from tobacco use and denormalizing tobacco use behaviors. The focus on individual behaviors is complemented by drawing attention to the deceptive practices of the tobacco industry; offering cessation supports in different institutional settings; promoting support for increased taxes on tobacco; and at the policy level, placing restrictions on marketing, advertising, and using tobacco in different localities, such as the workplace and restaurants (HHS, 2012b; IOM, 2007).

“I am not sure many people quit smoking because they see an ad from an anti-smoking campaign. I think it is more likely that smoking has negative health effects for them or someone they know and they decide at that point to make a change.”

While a large body of work addresses tobacco control interventions among teens and adults (NCI, 2008), interventions focused specifically on young adults have been somewhat limited. A Cochrane review examined the impact of mass media campaigns on smoking prevention among young people (under age 25) (Brinn et al., 2012). Media were defined broadly to include television, radio, newspapers, billboards, posters, leaflets, and booklets. The review examined 7 of 84 studies that met the inclusion criteria and found that they were conducted systematically, drew on sound theories and research-informed interventions, and used extended campaigns to ensure exposure. Brinn and colleagues (2012) report modest evidence that mass media interventions could be successful in the prevention of smoking among young people. In a review of 25 studies examining the effectiveness of multicomponent interventions in reducing smoking uptake among young people, Carson and colleagues (2011) report that one intervention generally was successful in reducing smoking in the short term, and nine showed significant long-term effects. Improvements also were seen in changes in intentions to smoke (six of eight interventions), improved attitudes (five of nine), risk perceptions (two of six), and knowledge of tobacco use (three of six).

In contrast, short-term and/or single-component interventions are less likely to be successful. Villanti and colleagues (2010) conducted a systematic review of 14 studies of interventions promoting smoking cessation among young adults in the United States. The interventions focused on

young adults aged 18-24 and were conducted in multiple settings, including universities, a community college, an airforce basic training unit, a quitline, and a rural community. Interventions were delivered either through interpersonal channels, such as peer coaches, counselors, and health educators, or a computer website. The authors report limited support for the efficacy of the interventions, although brief interventions with an extended dose via telephone or electronic media were somewhat effective. Villanti and colleagues (2010) recommend using standardized measures and interventions that take the smoking trajectories among young adults into account and are conducted among diverse population groups.

The use of electronic media, such as telephone quitlines and text messaging, to promote cessation of tobacco use has drawn the attention of several researchers. The Internet and social media hold considerable promise in promoting cessation. Sims and colleagues (2013) compared the effectiveness of cessation counseling through quitlines with a group receiving only mailed self-help material. They report only short-term effects among the group receiving counseling on the telephone. On the other hand, Brown (2013) reviewed eight studies assessing the impact of technology-based interventions that included tailored texts, emails, counseling, and a discussion board on tobacco use among participants aged 18-30 and found that in at least four studies, there was significant 7-day abstinence in the intervention group.

Similarly, Skov-Ettrup and colleagues (2014) report on a randomized controlled trial involving 2,030 daily smokers aged 15-25. The intervention arm received tailored text messages on self-efficacy, beliefs about smoking, and topics chosen by the user, whereas the control group received only generic messages. While there were no significant differences between the two groups in self-reported cessation, the researchers report higher rates of quitting among those in the tailored messaging group who used the text messages. That is, when the participants actually used the messages, the desired effects were much more likely to occur.

This review highlights four points when it comes to tobacco control interventions among young adults. First, comprehensive tobacco control strategies have had a demonstrable effect in reducing the prevalence and intensity of consumption at the population level (HHS, 2012b; IOM, 2007). Second, more focus is needed on developing and testing effective interventions targeting young adults, especially at a time when new tobacco products are being introduced at a rapid pace. Third, most of the interventions appear to have been carried out in colleges or white collar settings, and more effort needs to be made to include population groups of diverse racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic backgrounds. Last, the new information and communication technologies hold considerable promise in promoting tobacco control, but remain underexplored.

Alcohol Use

Alcohol consumption carries a risk of adverse health and social consequences and is the third leading cause of death in the United States (CDC, 2010). It can have a major impact on individuals, families, and communities that can have cumulative effects, contributing significantly to costly social, physical, mental, and public health problems. Alcohol use is associated with both short- and long-term health risks. Short-term risks, most often caused by binge drinking, include injuries, violence, risky sexual behaviors, miscarriages, and alcohol poisoning (CDC, 2014b). Long-term risks include neurological, cardiovascular, psychiatric, and social problems; cancer; liver diseases; and gastrointestinal problems (CDC, 2014b).

Most public health interventions targeting alcohol use by young adults have focused on college students. Paschall and colleagues (2011a,b) conducted a randomized controlled trial in 30 universities where freshmen were delivered an intervention designed to reduce alcohol use and binge drinking. The intervention was delivered over the Internet in two doses and covered such topics as alcohol laws, policies, and risks; setting personal goals; and dealing with friends with alcohol problems. A booster session was delivered 30-45 days later. Limited reductions in alcohol use and binge drinking occurred immediately following the intervention, but the effects did not persist until the second assessment, in the spring semester (Paschall et al., 2011a,b). In another Web-based screening and intervention program targeting college students aged 17-24, Kypri and colleagues (2014) found that intervention group students receiving personalized feedback and information correcting misperceptions of alcohol use among their peers reported only minimal effect. Both of these Internet-based studies show that use of the Internet alone may not be the most effective intervention strategy with respect to outcomes.

“When I was in college, we had a rule that if you saw somebody who was sick from too much alcohol or from using drugs, you wouldn’t get in trouble if you got them the help that they needed. People shouldn’t be punished for bad behavior; we should make sure they are getting access to health care.”

Similar modest effects were found by Moore and colleagues (2013) in a cluster randomized trial of students in residence halls in Wales, United Kingdom. The intervention focused on correcting misperceptions about the drinking behaviors of peers in order to reduce alcohol consumption. Messages were delivered through nonmedia channels such as posters, coasters,

meal planners, and stickers. There were no significant effects on perceived norms or alcohol consumption between the groups, although there were some other modest effects.

On the other hand, a more broad-based community organizing approach focused on changing the environment with respect to high-risk drinking behavior among college students in North Carolina showed positive outcomes (Wolfson et al., 2012). The intervention encompassed campus-community coalitions; action plans; community organizers in each school; and promotion of environmental strategies, including awareness, enforcement, and policy. It also involved correcting misperceptions about alcohol use and limiting exposure to pro-alcohol messages. The intervention had a significant impact on decreasing consequences due to students’ own drinking, such as requiring medical treatment, getting a driving under the influence/driving while intoxicated ticket, and being taken advantage of sexually, as well as on alcohol-related injuries caused to others. No differences, however, were seen in actual drinking behavior.

Many environmental policy interventions have been effective in decreasing drinking and driving and motor vehicle crashes that involve alcohol among young adults (Hingson, 2010). However, it has been found that for policies to be effective, they need to be put into action and enforced at the local level (Hingson, 2010). It also has been found that multicomponent college-community approaches among college students that incorporate a legal component can decrease alcohol use and drinking and driving (Hingson, 2010).

Three main lessons can be drawn from this review. First, most interventions addressing alcohol use problems among young adults appear to have been conducted among college students, with virtually little or no focus on noncollege youth. Second, single-component approaches (e.g., only promotion or policy) or those using a single channel (e.g., television) are not effective, while a multipronged approach focusing on both the environment and individual behaviors may be more effective. Schulenberg and Maggs (2002) point out that binge drinking at college campuses is multiply determined and held at high rates by a number of pillars ranging from community standards to students’ assumptions about their rights to party. Addressing just one of these pillars is insufficient because the others will pick up the slack and keep the rates high. Third, multimodal community-wide interventions, including legal enforcement, have been shown to reduce drunk driving and alcohol-involved crashes among young adults.

Chronic Disease Prevention

Many interventions for chronic disease prevention center on maintaining a healthy lifestyle and focus on prevention of weight gain, weight loss,

healthy eating, and physical activity. Obesity increases the risk of chronic illness and is associated with reduced quality of life and adult success, as well as substantial human and societal costs (IOM, 2012a). Individual effects include illness (e.g., cardiovascular disease, diabetes, hypertension), disability, social ostracism, discrimination, depression, and poor quality of life (IOM, 2012a). Moderate amounts of daily physical activity are recommended for people of all ages both to remain healthy and to improve health. A decline in physical activity is one of the lifestyle changes that can occur during young adulthood.

Many studies have targeted the transition to college, most often using the college setting to recruit participants and deliver intervention components. In one example, undergraduate health classes were used to administer a goal-setting intervention. Participants who wrote if-then statements about healthy eating goals significantly increased their fruit and vegetable consumption relative to participants assigned to a general goal-related task (Chapman et al., 2009). Likewise, over a 15-week period, a college class-based intervention involving 80 students that met three times per week, emphasizing healthy choices and in-class activities, also significantly increased the consumption of fruits and vegetables among participants (Ha and Caine-Bish, 2009). And a sample of college freshmen who were administered an alternative-reality game during a college health education course significantly increased their physical activity compared with controls, although both groups gained a significant amount of weight over the study period, suggesting that other factors in the college experience were impacting weight changes (Johnston et al., 2012).

Online sources also have been used to influence healthy behaviors and weight loss, again in a college setting. For example, Gow and colleagues (2010) administered an intervention using an Internet classroom tool, finding that participants who received the intensive 6-week intervention with feedback on their weight had significantly lower body mass index than controls. The authors note that the combination of monitoring, feedback, and education had a stronger effect on behavior than each component separately. In another study, an Internet-based curriculum that provided 10 online lessons focused on healthy eating and physical activity to students across eight universities significantly increased fruit and vegetable intake and physical activity, with positive, lasting effects being seen over the course of 15-month follow-up (Greene et al., 2012). In another study, however, although an intervention using texts, emails, and a smartphone application led to decreases in body weight and increases in physical activity and healthy eating among the intervention group, no significant differences were observed relative to the control group (Hebden et al., 2014).

Reviews of weight loss interventions among young adults have shown mixed results. Interventions combining diet, exercise, and motivation con-

sistently show weight loss among young adults, although because of the varied components of these interventions, determining what elements are the most effective is problematic (Poobalan et al., 2010). Another review of 37 studies found that university course-based interventions often resulted in weight loss, with many self-monitoring interventions showing positive results as well (Laska et al., 2012). However, both reviews highlight the need to develop and evaluate rigorous weight gain prevention interventions focused on young adults that fully reflect the rapidly shifting life circumstances of this age group and incorporate more diverse populations.

Studies in this area have shown varying degrees of success. Many of the researchers acknowledge that an environmental approach is necessary to fully address the range of issues faced by young adults as they transition into making their own health-related choices, including pressure to engage in certain harmful behaviors.

Prevention of Sexually Transmitted Infections/HIV

STIs are infections that are transmitted primarily through sexual contact. Although they are largely preventable, they remain a significant public health concern, and some have the potential to cause serious health problems, especially if not diagnosed and treated early. The consequences of untreated STIs often are worse for young women than for young men, even though the yearly number of new infections is roughly equal among them (51 percent and 49 percent, respectively) (CDC, 2013c). Although HIV transmission is generally preventable, there is no vaccine or cure. As a result, HIV continues to be a major public health concern.

Several strategies have addressed STI and HIV prevention among diverse samples of young adults across a number of settings, often focusing on increasing condom use and decreasing risky sexual practices. In their sample of U.S. university students aged 18 and older, Norton and colleagues (2012) found that participants exposed to a 60-minute DVD addressing motivation, information, and behavioral skills with respect to increasing condom use and decreasing risky sexual practices changed these behaviors more when the topic was prevention of STIs or unplanned pregnancy than when it was HIV prevention.

Community-based participatory research was used to create a culturally congruent HIV prevention intervention, AMIGAS (Amigas, Mujeres Latinas, Inform andonos, Gui andonos, y Apoy andonos contra el SIDA [friends, Latina women, informing each other, guiding each other, and supporting each other against AIDS]), for young Latina women living in Miami, Florida, modeled after the evidence-based SiSTA (Sistas Informing Sistas about Topics on AIDS) program for African American women (DiClemente and Wingood, 1995; Wingood et al., 2011a). Within the

AMIGAS intervention, Latina health educators delivered four interactive group sessions emphasizing cultural and gender pride, the importance of healthy relationships, HIV knowledge, and how experiences unique to Latina women may increase HIV risk (Wingood et al., 2011a). At the 6-month follow-up, program participants reported significantly more consistent condom use, greater self-efficacy for negotiating safe sex, greater HIV knowledge, and fewer perceived barriers to using condoms compared with controls.

Several studies have targeted African American young adults in various community- and technology-based settings for the reduction of HIV risk behaviors. Aronson and colleagues (2013) developed a pilot intervention with 57 participants that used community-based participatory research partnerships among students, university faculty, and community partners to create a retreat for young adult African American men in which to discuss safe sex, followed by reinforcement messages via electronic media over the course of 3 months. Average number of sex partners and condom errors decreased significantly among participants, with the authors attributing much of this success to the high level of engagement with community partners. In a pilot study by Kennedy and colleagues (2013), a theory-driven, single-session condom promotion program delivered to 18- to 24-year-old African American men recruited from neighborhoods bordering urban community centers significantly increased condom use, perceived condom availability, and positive reasons to use condoms compared with a comparison group that received a general health curriculum. Results suggest that this brief, culturally appropriate prevention program may reduce risky sexual behaviors among high-risk youth from urban communities.

An HIV intervention for young African American women at Planned Parenthood in Atlanta, Georgia, used two computer-based 60-minute interactive sessions also modeled after the SiSTA program (DiClemente and Wingood, 1995; Wingood et al., 2011b). The intervention significantly increased knowledge of HIV prevention, condom self-efficacy, and condom use in participants compared with a control group that received a small-group session on general health topics (Wingood et al., 2011b). Another intervention with low-income African American young women at high risk for HIV used smartphones to stream a soap opera highlighting HIV risk reduction (Jones et al., 2013). Although no statistically significant differences were seen between the intervention and control groups, participants who viewed the videos found them engaging and wished to continue receiving them, prompting further research on how to reach this population on a popular messaging platform.

International studies also have shown success. A Dutch Web-based study involved a tailored intervention for young adults that used a virtual clinic with motivational interviewing, participant-specific feedback, and educational models. Significantly higher condom use and maintenance re-

sulted from the intervention compared with general feedback or treatment as usual (Mevissen et al., 2011). A study in India found that a workplace-based PowerPoint, video, and training session significantly increased positive perceptions of condoms and knowledge of proper wearing techniques among males aged 18-30 (Ray et al., 2012). The authors emphasize that simply providing knowledge may not be sufficient, and that a range of education on behavior, perception, and skill may be needed with this group.

In sum, many interventions targeting STI or HIV prevention saw success when they focused on topics most relevant to young adults; included culturally competent, tailored materials; and introduced skill components along with this tailored feedback.

Human Papillomavirus (HPV) Vaccination

HPV vaccination, recommended for females under 26 and males under 21, entails a series of three shots that protect against HPV infection and HPV’s associated health problems, such as cancer and genital warts (CDC, 2014c). Brief intervention techniques highlighting the benefits of HPV vaccination have been shown to increase positive perceptions of the vaccine and increase vaccination intention and reception. For example, Kester and colleagues (2014) recruited a sample of 18- to 26-year-olds at a minority health fair. Intervention group participants received a 5- to 10-minute small-group presentation on HPV infection, detection, and treatment; additional information sources; and a list of locations where the vaccine could be received. Participants had higher HPV knowledge scores and vaccination intention compared with controls.

HPV education also has been delivered to university populations in school computer labs. Intentions to be vaccinated increased significantly among women viewing an HPV website that provided information tailored to their specific perceived barriers to vaccination compared with women who viewed standard information (Gerend et al., 2013). Short videos also were used by Hopfer (2012), with intervention groups watching videos narrated by peers, medical experts, or both, while another arm reviewed a generic video or HPV website or received no message. HPV vaccination nearly doubled among the participants who watched the combined peer-expert video compared with controls; however, these results were not found for the peer- or expert-only videos, highlighting the importance of the communication source and suggesting that peer messages that normalize medical expert messages may play a crucial role in vaccination.

Direct provision of information about HPV and HPV vaccination may be a simple and effective way to motivate young adults to initiate HPV vaccination (Kester et al., 2014). Tailoring this information to ameliorating or removing specific barriers may enhance the effectiveness of this approach (Gerend et al., 2013).

Sexual Assault and Intimate Partner Violence

Black and colleagues (2011) found that nearly 1 in 5 women and 1 in 17 men reported experiencing rape at some point in their lives (Black et al., 2011). Approximately 1 in 20 women and men (5.6 percent and 5.3 percent, respectively) had experienced sexual violence other than rape.

Several interventions have sought to address sexual assault by providing girls and women tools needed to prevent these acts from occurring. One study focused on the transition of young adult women to the college environment, enlisting their mothers to participate with them the summer prior to their freshmen year (Testa et al., 2010). Mothers in the intervention condition were advised to complete a workbook on alcohol safety with their daughter before the start of school, with participants in the enhanced intervention condition also receiving a workbook chapter on college dating. Both intervention conditions were correlated with decreased incapacitated rape levels during the first year and increased communication among mothers and daughters, which predicted fewer drinking episodes, leading to lower sexual victimization rates involving alcohol.

Another study delivered an intervention for women to promote group responsibility, environmental awareness, and safe personal conduct as groups of college-aged students crossed the border to patronize Tijuana bars. The program led to a significant decrease in reports of sexual victimization (Kelley-Baker et al., 2011). Other strategies have focused on both men and women. A Web-based intervention for college students who were in longer-term relationships advised them on problem solving, communication techniques, and ways to enhance positive relationships, with weekly reminders to employ these skills (Braithwaite and Fincham, 2009). Intervention participants experienced improved mental health and relationship outcomes that continued over time, although anxiety, physical assault, and aggression grew worse before they ultimately improved.

Despite these findings, a meta-analytic Cochrane review of education- and skill-based interventions designed to reduce violence in the context of relationships and dating among youth aged 12-25 found no evidence of a significant effect on relationship violence episodes or on attitudes toward violence (Fellmeth et al., 2013). The 38 interventions included in the review were predominantly educational, and components were delivered in such settings as college classrooms, dorms, and fraternity halls, with sample populations ranging from coed to all-male or all-female. Intervention strategies included group discussions, videos of dramatic vignettes, role playing, problem solving and communication skills, and discussion of rape myths. Despite a trend found in increased knowledge about relationship violence, there was no evidence that these strategies improved participants’ attitudes, actions, or proficiency with respect to violence in relationships. The authors

highlight that the existing evidence relates primarily to determining changes in attitudes and knowledge, and that interventions both across communities and within families may be needed to reduce relationship violence. Further studies with longer-term follow-up and validated, standardized measures also are required to maximize the comparability of results (Fellmeth et al., 2013).

Mental Health Conditions

Mental health and substance use disorders are public health concerns for numerous reasons. First, they can cause death through the act of suicide. Mental health and substance use disorders also affect families and harm individuals by reducing their ability to achieve social, educational, and vocational goals; increasing the potential for further impairment and compromised functioning throughout life; and imposing costs related to extra care requirements and social disruption (NRC and IOM, 2009; Patel et al., 2007), as well as lost productivity (Birmbaum et al., 2010; Kessler et al., 2006). Of all types of illnesses, moreover, mental health and substance use disorders cause the greatest burden of disability in young adults (IOM and NRC, 2013). Furthermore, given the age of onset of behavioral health conditions, preventing or addressing mental and behavioral health needs in this period of life has the potential to reduce lifelong impact, since many fewer new cases occur after age 24 (Kessler et al., 2005). Timely mental health intervention can reduce morbidity and increase long-term health and well-being.

“I have severe mental health issues that I haven’t addressed yet because I don’t want to go to a therapist. I don’t feel comfortable. Why am I going to go to this person and tell them my problems? After what I went through, I have a hard time trusting people to talk about my problems.”

In addition, although not a psychiatric disorder, the experience of stress is pervasive in young adults (APA, 2013). Compared with older adults, young adults experience greater levels of daily stressors (Stawski et al., 2008) and perceive their lives as more stressful (Scott et al., 2013). One of the benefits of maturity appears to be coping better with stressful situations (Luong and Charles, 2014; Price and Dunlap, 1988; Schilling and Diehl, 2014). Even among young adults, the youngest struggle more with stressful events than their slightly older counterparts (Jackson and Finney, 2002). Psychological stress can contribute to the onset of mental illness (Blazer et al., 1987;

Corcoran et al., 2003; Kendler et al., 1999; Muscatell et al., 2009), and its relationship to physical health is well established (McEwen, 2008; McEwen and Gianaros, 2010).

Although mental health treatment is available and effective (HHS, 1999; NIH, 2009; NIMH, 2000), young people, especially young men and young indigenous and ethnic minorities, are reluctant to obtain professional care for problems relating to mental health (Edlund et al., 2012; Gulliver et al., 2010; Rickwood et al., 2007; Wu et al., 2007). Other studies have found that only about 18-34 percent of young people with depression and anxiety disorders seek professional help (Guilliver et al., 2010). Friends and family members rather than health professionals are preferred sources of help (Rickwood et al., 2007). Likewise, Wu and colleagues (2007) found that approximately 4 percent of full-time college students, 7 percent of part-time college students, and 6 percent of nonstudents aged 18-22 with an alcohol use disorder had sought help within the past year. Gayman and colleagues (2011) found that only about one-third of young adults with a substance use disorder had ever sought help; those in whom the onset of the disorder occurred at 18 or older were less likely to have sought help than those whose onset occurred earlier.

Perceived barriers to young adults’ seeking help for behavioral health disorders include stigma and embarrassment, difficulty recognizing symptoms or the need for treatment (i.e., lack of behavioral health literacy), a preference for self-reliance, and lack of confidence that their insurance will pay for treatment (Cellucci et al., 2006; Eisenberg et al., 2007; Gulliver et al., 2010; van der Pol et al., 2013). Perceiving the need for help or being encouraged by family, friends, or others to seek help increases the likelihood of help seeking (Caldeira et al., 2009).

The mental health literacy of young adults is not high (Farrer et al., 2008). Studies in Australia found that fewer than 50 percent of 12- to 25-year-olds could identify depression, and only about 25 percent could identify psychosis (Wright et al., 2005). Rates of recognition are lower in young men than in young women (Cotton et al., 2006). Lack of mental health literacy is regularly given as one of the explanations for missed opportunities to intervene with individuals with serious mental illness (Gulliver et al., 2010; IOM, 2004; Jorm, 2012).

As noted, the stigma attached to having a behavioral health disorder is one important impediment to help seeking by young people, and reducing stigma also is one of the major policy approaches proposed for reducing levels of unmet need for mental health services (HHS, 1999). Public stigma is the reaction of the general population toward a condition; self-stigma is the internalized impact of public stigma, and thus the prejudice people with behavioral health conditions turn against themselves (Corrigan and Watson, 2002); and personal stigma is the reaction

of an individual. All three forms of stigma can reduce willingness to seek behavioral health services (Eisenberg et al., 2009; Held and Owens, 2013), with some evidence suggesting that personal stigma may be a stronger disincentive than public stigma for college students (Eisenberg et al., 2009; Lally et al., 2013). Personal stigma also may pose a barrier to help seeking by reducing recognition of the impact of symptoms and thus the need for help (Schomerus et al., 2012). Generally, however, the specific roles of the various forms of stigma in help seeking are not well understood, specifically in young adults with behavioral health conditions. Many of the studies of public and self-stigma and help seeking in young adults examined these issues in general populations, most of whom did not have a behavioral health disorder.

One study illustrates the potential for unexpected and counterproductive consequences of public service announcements designed to reduce stigma; the announcements actually increased self-stigma and reduced help seeking in individuals with depression (Lienemann et al., 2013). In addition, help-seeking intentions have been studied much more thoroughly than actual help seeking. Thus, any public health campaign to reduce the stigma of behavioral health conditions and encourage help seeking for these conditions should be informed by research aimed at understanding the impact of stigma and of various types of public service announcements on help-seeking behavior in a wide range of young adults with behavioral health disorders.

A further impediment to adequate treatment of behavioral health disorders in young adults is that they are more likely than older adults to drop out of treatment once they have started (Edlund et al., 2002; Hadley et al., 2001; Sinha et al., 2003).

The onset of many mental health conditions during the young adult years has prompted a range of strategies aimed at preventing or treating mental health conditions in this population. A review of community-based prevention and early intervention programs found that the majority of interventions for young adults focus on strategies employing cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), which has shown the most reliably positive outcomes for treatment of anxiety or depression (Christensen et al., 2010). A later review focused on technology use among 18- to 25-year-old college students found that of diverse strategies employing the Internet, video, and audio, Internet-based strategies using CBT may be particularly useful for targeting anxiety, and to a lesser extent depression (Farrer et al., 2013). The authors conclude that the use of technological interventions targeting certain mental health problems holds promise for students in university settings, although more research is needed to assess the use of technology for other specific mental disorders. A review of 15 interventions targeting prevention of suicide and self-harm among 12- to 25-year-olds found highly

limited evidence regarding effective interventions for young adults experiencing suicide attempts, deliberate self-harm, or suicidal ideation (Robinson et al., 2011). While the authors acknowledge that CBT may show some promise, more methodologically rigorous trials of this approach are needed (Robinson et al., 2011).

Motor Vehicle Safety

Motor vehicle safety is a major concern for young adults, particularly since, compared with adolescents and adults aged 26-34, young adults (aged 18-25) are more likely to be injured or die in motor vehicle crashes and have more motor vehicle crash-related hospitalizations and emergency room visits (Neinstein, 2013). Historically, actions to prevent motor vehicle crashes and resulting injuries and deaths have taken an ecological approach, including multiple levels of influence such as policy designed to increase seat belt use. Indeed, the most notable road safety campaigns have promoted and enforced seat belt use (Dinh-Zarr et al., 2001) and have used enforcement campaigns to increase their use (Wakefield et al., 2010). For example, the Click It or Ticket program in North Carolina was associated with an increase in seat belt use from 63 percent to 81 percent and lower rates of highway deaths and injuries (Williams et al., 1996). Increasingly, states also are passing laws banning texting while driving, and in some cases any use of cell phones by drivers under age 18, to address distracted driving, a significant factor in motor vehicle crashes (NHTSA, 2014).

“The ‘Distracted Driving’ campaign was interesting and impactful, but I still struggle with being on the phone when driving. Laws about using the phone while driving seem to be making more of an impact than the campaign by itself.”