Key Findings

- Young adults have significantly lower rates of health care system utilization compared with other groups, but significantly higher emergency room visit rates compared with those immediately younger and older than them. These lower utilization rates do not necessarily indicate better health; for example, the use of specialty psychiatric services by those with mental health conditions falls from approximately 20 percent of adolescents to about 10 percent of young adults.

- The transition from child to adult medical and behavioral health care often is associated with poor outcomes among young adults. Challenges include discontinuities in care, differences between the child/adolescent and adult health systems, a lack of available adult providers, difficulties in breaking the bond with pediatric providers, lack of payment for transition support, a lack of training in childhood-onset conditions among adult providers, the failure of pediatric providers to prepare adolescents for an adult model of care, and a lack of communication between pediatric and adult providers and systems of care.

- Young adulthood provides an important opportunity for prevention. Serious illnesses and disorders can be avoided or mana-

-

ged better if young adults are engaged in wellness practices and screened for early signs of or untreated illness, and the risk taking that is common during these years can impact lifelong functioning. Yet young adults rarely receive preventive counseling on important issues for this age group, such as smoking and mental health, and there is no consolidated package of preventive medical, behavioral, and oral health guidelines specifically focused on the young adult population.

- While there are effective behavioral health treatments and strategies for adults, the efficacy of these treatments specifically for young adults is largely undemonstrated because typical clinical trials and research studies (e.g., studies of adults aged 18-55) are insufficient to establish efficacy in young adults.

- Young adults without health insurance or with gaps in insurance coverage are less likely to access health services than young adults who are continuously insured. Health insurance coverage rates for young adults, however, have historically been the lowest of any age group. Certain groups of young adults—such as young adults exiting the foster care system, young adults involved in the justice system, and unauthorized immigrants—have particular difficulties in obtaining health care coverage. The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act and state-level efforts are increasing coverage for many young adults, including young adults who age out of the foster care system, but others, such as unauthorized immigrants, remain outside the system.

Young adults often are perceived as healthy and as low users of health care, and recent attention has focused primarily on enrolling young adults in health care insurance to offset the higher costs associated with care for older adults. However, while young adults are clearly an important priority population for health insurance coverage, there also needs to be an expanded focus on improving the health care system’s ability and capacity to serve them. Important opportunities exist within the health care system to improve young adults’ health, safety, and well-being in both the short and long terms. Yet many young adults face serious challenges in accessing and navigating the health care system, with potentially serious repercussions.

Young adulthood provides an important opportunity for prevention. Serious illnesses or disorders can be avoided or managed better if young adults are engaged in wellness practices and screened for early signs of

or untreated illness. Furthermore, as described in earlier chapters, young adulthood is an age not only of opportunities, but also of risks that can impact lifelong functioning. Keeping young adults as healthy as possible during this critical stage of life may support more positive pathways into mature adulthood. Young adulthood also provides an opportunity to help young adults access and learn to navigate the adult health care system and develop the ability to work directly with health care providers to manage their health care more effectively.

Among the many young adults who are parents, moreover, there is an opportunity to minimize the potential impact of their behavioral and physical health problems on their children. For example, alcohol, tobacco, or drug use during pregnancy increases the likelihood of long-term cognitive and emotional development problems, such as attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), conduct problems, and lower school achievement, in the child (Knopik, 2009; Minnes et al., 2011). And children of depressed parents have three times the risk of anxiety disorders, major depression, and substance dependence compared with children of nondepressed parents (Weissman et al., 2006). Use of cognitive-behavioral therapies with parents with mental illness can help reduce mental health disorders in their children (Siegenthaler et al., 2012).

In addition to the challenges that almost all adults face in accessing and navigating a complicated health system, two challenges are particularly relevant for young adults: the transition from child to adult systems and the onset of certain health conditions, such as serious mental illness. Young adults are transitioning from pediatric to adult health care providers and from the child to the adult behavioral health system, and these new systems of care often differ significantly from those they used as children and adolescents. Some struggle as they assume primary responsibility for their health care for the first time. The health system may not be set up in ways that young adults find easy to use, and providers sometimes lack young adult–specific content knowledge and the skills needed to work effectively with this age group. This transition is widely recognized as challenging for those with

“Even with insurance, it is still hard to access health care. It is so complicated and you don’t really learn in school how to navigate it.”*

__________________

* Quotations are from members of the young adult advisory group during their discussions with the committee.

chronic illness, but it is also essential that all young adults make a successful transition to the adult health care system to ensure they receive preventive services that help them remain in good health, as well as the comprehensive array of physical and behavioral health services many of them need. Box 7-1 summarizes barriers discussed in the remainder of this chapter that impede young adults from accessing and continuing to use health care.

BOX 7-1

Barriers to Optimal Health Care for Young Adults

The following are barriers faced by young adults in accessing care and/or continuing to receive care in the health care system:

- Transitions

- − navigating the differences between pediatric and adult health care providers, including differences in treatment culture, family involvement, and care coordination;

- − discontinuity of care caused by age-based changes in eligibility criteria or target populations for behavioral health services and management of chronic medical conditions; and

- − changes in insurance coverage.

- Content

- − no unified set of young adult preventive care guidelines; and

- − significant gaps in interventions and treatments with strong evidence of efficacy for young adults, particularly in preventive and behavioral health.

- Cost and difficulty of obtaining health care coverage.

- Young adults’ lack of health literacy and knowledge of how to access and complete the enrollment process, identify providers in the community, and navigate the health system.

- The stigma of behavioral health and substance abuse problems.

- Systems issues

- − few incentives to provide transition care, preventive care, counseling, and health education, particularly about treatment for or early signs of mental health problems and risk behaviors such as substance use;

- − inconsistency among pediatric systems in offering adolescent patients and their families preparation and planning for the transition to adult systems and for an adult model of care;

- − adult systems’ being unfamiliar with how to engage and integrate young adults into their practice;

- − inadequate health care provider training and skills for caring for adult manifestations of childhood diseases; and

- − confidentiality concerns.

Health systems are currently undergoing significant changes that affect both young adults and the general population. A key provision of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) is the requirement that health insurance plans extend dependent coverage so that young adults can be added to a parent’s plan until they turn 26; several states also had initiated expansion of insurance coverage before the ACA was enacted (Blum et al., in press). Driven by advocacy goals and the fiscal need to enroll healthy individuals to offset the cost of older and sicker individuals, the White House, states, health insurance companies, and advocacy organizations across the country have recently developed campaigns to increase young adult enrollment in insurance plans (e.g., Colorado Consumer Health Initiative and ProgressNow Colorado Education, 2014; HealthSource RI, 2014; Ostrom, 2014; Young Invincibles, 2014). Results of a 2013 survey indicate that of 15 million 19- to 25-year-olds who enrolled in a parent’s plan, 7.8 million would not have been able to do so prior to the ACA (Collins et al., 2013). In addition, federal surveys suggest that 1-3 million previously uninsured young adults have gained coverage since this provision took effect (Blumenthal and Collins, 2014). This change is likely to have a significant impact on young adults’ relationship with the structure and content of the health care system for years to come, and the evolving system offers opportunities for integrating further changes to benefit young adults.

In this chapter, we examine young adults in the health care system and provide recommendations for improving the system’s role in enhancing their health, safety, and well-being. As described in Chapter 1, the term health care is used broadly in this report to include both physical and behavioral health, and the term behavioral health encompasses the promotion of emotional health; the prevention of mental and substance use disorders; and treatments and services for substance abuse, addiction, and mental and substance use disorders (SAMHSA, 2011). Since the epidemiology of young adults is covered in greater depth in Chapters 2 and 6, this chapter focuses on health care delivery.

We first briefly describe where young adults currently receive health care services and what services they use. We then explore in turn transitions from pediatric to adult medical health care systems and from child to adult behavioral health care systems, preventive care for young adults, behavioral health interventions for young adults, health care coverage, and systems issues related to young adults. The chapter ends with conclusions and recommendations for improving health care for young adults. Note that the primary recommendations offered in this chapter are applicable to health systems in a variety of forms and are not restricted to specific implementations of the ACA. Some of our suggestions are not exclusive to young adults, but with the current large influx of young adults into the

system, there is an opportunity to think about how to get the system right for them and then extend it to others.

CURRENT USE OF HEALTH CARE BY YOUNG ADULTS

Comprehensive care with a medical home does not appear to characterize the health care delivery system for young adults as compared with children and adults (for a discussion of medical homes for 10- to 17-year-olds, see Adams et al., 2013).1 An analysis of health care utilization conducted before the passage of the ACA found that young adults had significantly lower health care system utilization rates than other groups (see Table 7-1). Specifically, this age group had significantly lower rates of office-based and dental visits. Of interest is that young adults had significantly higher emergency room visit rates compared with those immediately younger and older than them. In addition, the use of specialty psychiatric services by those with mental health conditions falls from approximately 20 percent of adolescents to about 10 percent of young adults (Copeland et al., in press). The use of services in general—including medical care, educational and job services, and services provided through organizations such as Big Brother—by individuals with mental health conditions drops from about half of adolescents to a quarter of young adults.

“I would like to receive my health information from my doctor. The problem here is that I only go to the doctor when things go wrong, as do many other young adults.”

The prevalence and trends of the major health-related problems affecting young adults are discussed extensively in Chapters 2 and 6. Table 7-2 highlights the percentages of young adults utilizing the various types of health care services. This table shows that small percentages of young adults received care for substance use and mental health disorders, even though more than 50 percent reported having a usual source of care and having received a routine general checkup within the past 12 months, and even though early young adulthood is often when the burden of illness emerges for substance abuse and mental health conditions. Emergency rooms represent a major component of care for young adults, utilized by an estimated 15 to 20 percent of this age group (Fortuna et al., 2010; Lau et al., 2014a), although evidence from three states suggests that the ACA

__________________

1 The patient-centered medical home is a model for primary care that promotes effective care coordination, accessibility, quality, and safety (AAFP et al., 2007; IOM, 2013a).

TABLE 7-1 Past-Year Health Care Utilization Rates by Age Group: 2009 Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (rates adjusted for pregnancy)

| Children (aged 0-11) | Adolescents (aged 12-17) | Young Adults (aged 18-25) | Adult (aged 26-44) | Adult (aged 45-64) | Adult (aged 65+) | |

| Utilization % had any health care utilization |

88%*** | 83%*** | 72% | 78%*** | 89%*** | 97%*** |

| Office-based visits % had visit(s) |

77%*** | 67%*** | 55% | 65%*** | 79%*** | 91%*** |

| Hospital outpatient visits % had visit(s) |

7% | 5%* | 7% | 12%*** | 20%*** | 30%*** |

| Emergency room visits % had visit(s) |

15% | 12%** | 15% | 12%** | 12%*** | 17% |

| Inpatient hospitalizations % had visit(s) |

2%*** | 4%*** | 5% | 6% | 7%* | 19%*** |

| Prescription medications % had prescription(s) |

50% | 49% | 48% | 57%*** | 75%*** | 92%*** |

| Dental visits % had visit(s) |

44%*** | 53%*** | 34% | 37%* | 47%*** | 44%*** |

NOTES: Hospital outpatient visits are to general clinics that are hospital-based. ***p<0.001, **p<0.01, *p<0.05.

SOURCES: Adapted from Lau et al., 2013a, 2014a.

TABLE 7-2 Health Service Utilization by Type of Service

| Variable | Year | % | Source |

| Preventive Care: Attended a preventive care visit within the past 12 months (ages 18-25) | 2011 | 48 | MEPS |

| Mental Health: Received any mental health treatment/counseling in the past year (does not include substance abuse treatment) (ages 18-25) | 2012 | 12 | NSDUH |

| Substance Abuse: Received treatment at any location for illegal drug or alcohol use in the past year (ages 18-25) | 2012 | 2.4 | NSDUH |

| Reproductive Health: Among all women (ages 20-24), used sexual and reproductive health services | 2006-2010 | 72 | NSFG |

| Reproductive Health: Among sexually experienced women (ages 20-24), used | 2006-2010 | NSFG | |

|

Any sexual and reproductive health services |

81 | ||

|

Contraceptive services |

64 | ||

|

Services for sexually transmitted infections (STIs) |

30 | ||

| Emergency Care: Proportion of young adults’ (ages 20-29) health care visits occurring in the emergency department | 2006 | 22 | NAMCS |

| Dental Care: Had a dental visit in the past 12 months (ages 19-25) | 2012 | 59 | NHIS |

NOTE: MEPS = Medical Expenditure Panel Survey; NAMCS = National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey; NHIS = National Health Information Survey; NSDUH = National Survey on Drug Use and Health; NSFG = National Survey of Family Growth.

SOURCES: MEPS: Lau et al., 2014b; NAMCS: Fortuna et al., 2010; NHIS: Vujicic et al., 2014; NSDUH: SAMHSA, 2013a,b; NSFG: Hall et al., 2012.

has reduced emergency department use (Hernandez-Boussard et al., 2014). There appear to be no population data documenting the use of services for management of chronic medical or mental health conditions for young adults.

Most young adults face the challenge of accessing a new health care system and new health care team independently of their parents or guardians. In addition to the differences between pediatric and adult health care systems and the possibility that the adult system is less well suited to their developmental stage, they may have changes in insurance coverage and face confidentiality concerns. These challenges are amplified when the young

adult has a chronic physical or mental health condition that requires ongoing coordinated care. Pediatric providers may not prepare adolescents for an adult model of care, and there is a lack of adult providers who are familiar with managing the adult progression of childhood chronic diseases (AAP et al., 2011). In this section, we first examine the transition from pediatric to adult medical health care for young adults with chronic health conditions, and we then we explore transitions in behavioral health care and substance abuse treatment. While much of the published literature focuses on the transition challenges for those with chronic illness, requiring close medical care, there appears to be no systematic coordination of the transition to adult care for those without chronic medical conditions. It is important to improve the transition process for all youth moving to the adult health care system, not just those who have identified chronic medical conditions.

“Even if you have private insurance and you are transitioning from pediatric care to adult care, you are just kind of on your own in terms of finding doctors, in terms of figuring out how the system works. I didn’t particularly have anybody to help me go through that process. I had to figure it out on my own. I am still figuring it out.”

Transitions for Young Adults with Chronic Health Conditions

As noted, most transition research has focused on young adults with chronic health conditions, including cystic fibrosis, rheumatological diseases, diabetes mellitus, sickle cell anemia, acute lymphocytic leukemia (ALL), organ transplant, inflammatory bowel disease, and congenital heart disease (CHD). In this context, transition has been defined as “the purposeful, planned movement of adolescents and young adults with chronic physical and medical conditions from child-centered to adult-oriented health care systems” (Blum et al., 1993, p. 570). Although it is recommended that transition planning begin during early adolescence, expert consensus suggests that the actual transfer should generally occur during the early young adult years, between ages 18 and 21 (AAP et al., 2011). Before young adults reach the age at which they can legally make their own decisions regarding their care, which could include discontinuing or not accepting available treatment, it is important that they understand their own health conditions and have the tools needed to make such decisions.

The transition from pediatric to adult care is a time of vulnerability

that can result in poor outcomes among individuals with chronic health conditions. Poor health outcomes can result from discontinuities of care during the transition process itself, including difficulties identifying a new care team. In a survey of more than 900 adults with CHD, 42 percent reported a lapse of care of more than 3 years, and 8 percent reported a lapse of greater than 10 years; the most frequent age at which lapses occurred was 20 (Gurvitz et al., 2013). Further, a study of 360 young adults (aged 19-21) in Canada with CHD showed that more than one-quarter had not seen a cardiologist since the age of 18 (Reid et al., 2004). These health care lapses among young adults with CHD result in poor health outcomes (Kovacs and McCrindle, 2014).

Concerns also arise regarding young adults’ health outcomes after they have transitioned into adult care. For example, a study of 185 participants found that young adults with diabetes had poor glycemic control after they transitioned from pediatric to adult care compared with those young adults who did not make this transition (Lotstein et al., 2013). A large retrospective study of sickle cell disease–related emergency department visits and hospitalizations found that young adults aged 18-30 had higher rates of acute care encounters and rehospitalizations compared with those immediately younger and older (Brousseau et al., 2010). A longitudinal study of individuals with sickle cell disease also found that deaths most frequently occurred after age 18 and after the transfer to adult care (Quinn et al., 2010), although stronger data are needed to fully support the conclusion that the transfer caused the poorer outcomes (DeBaun and Telfair, 2012). In addition, a recent study found increased intubation risk and longer lengths of stay for those young adults (aged 16-25) with sickle cell disease and acute chest syndrome who were cared for in adult hospitals versus those who were cared for in pediatric hospitals (Jan et al., 2013).

Barriers to implementing an effective system to improve transitions have been well documented (e.g., McManus et al., 2008). Some of the critical barriers include those mentioned above: a lack of trained adult providers able to accept young adults with adult manifestations of childhood chronic illnesses, apprehension among patients and families and pediatric providers that care will be compromised during transition, lack of reimbursement for recommended transition practices, a lack of tools with which to assess readiness for transition, and a lack of time for the provider (McManus et al., 2008). The uptake of better practices also has been hampered by the lack of widespread dissemination of research findings.

Despite these challenges, it is possible to plan for a smooth transition with good outcomes. In the case of cystic fibrosis, a chronic illness for which more programs have been implemented for transition care relative to most childhood conditions, a recent study contradicts many previous studies, finding that those who transitioned to adult care had a less rapid

decline in respiratory status than patients with similar characteristics who stayed in pediatric care (Tuchman and Schwartz, 2013). These inconsistent research results necessitate greater focus on what constitutes the content of the most effective health care for these and other populations of young adults.

Along with increases in life expectancy in recent decades, many more children with serious childhood-onset diseases are now living into the young adult years. For example, 25 years ago, approximately 30 percent of people with cystic fibrosis were age 18 or older, whereas today approximately half of people with cystic fibrosis are adults, and the median predicted survival age is over 40 (CFF, 2012). This change underscores the need for a successful transition to adult health care. Next we further explore reasons behind the poor outcomes associated with that transition.

Limitations of Adult Health Care Providers’ Familiarity with the Disease Process and Developmental Needs of Young Adults

Because many individuals with serious congenital and childhood-onset diseases are now living into the young adult years, many are now receiving care from adult-focused health professionals who previously did not see patients with these diseases and may not have received training in these areas (e.g., Tuchman et al., 2010). From a neurosurgery perspective, for example, caring for an individual with childhood-onset hydrocephalus is very different from caring for an adult in whom this condition emerged as a result of hemorrhage, infection, or tumor (Simon et al., 2009). In a survey, only 15 percent of general internists felt comfortable providing primary care to adults with cystic fibrosis, and 32 percent felt comfortable providing primary care to adults with sickle cell disease (Okumura et al., 2008). In another survey, a lack of training was cited by 24 percent of general internists as a significant or severe limitation on their ability to treat young adults with childhood-onset chronic diseases, although these reports were not statistically associated with physicians’ perceived quality of care (Okumura et al., 2010).

In addition, disease manifestation in young adults may differ from that in older adults. Health care providers who provide care for conditions that most commonly affect older adults, such as cancer, may be less familiar with the disease process in young adults. Studies on adolescent and young adult oncology training for health professionals have emphasized the importance of understanding tumor biology, pointing out that the epidemiology and biology are different for many cancers in adolescents and young

adults compared with children and older adults (Bleyer and Barr, 2009; Bleyer et al., 2008; Hayes-Lattin et al., 2010).2 Similarly, young adults may have different concerns and psychosocial needs than older adults. For example, fertility preservation is a great concern for young adults with cancer (Gupta et al., 2013). Young adults with cancer also have a high desire for information and services in the areas of cancer diagnosis, nutrition, physical activity, complementary and alternative services, and health insurance assistance (Gupta et al., 2013; Zebrack, 2008). However, research also indicates that these needs frequently go unmet; in a survey of 217 young adults with cancer, 40-50 percent of respondents indicated that these needs were unmet (Zebrack, 2008). These young adults also expressed needs for or interests in services and supports such as “camp programs and retreats, counseling or guidance related to sexuality, counseling for family members, infertility treatment and adoption services, transportation assistance, child care, and alcohol or drug abuse counseling” (Zebrack, 2008, p. 1). Again, more than 50 percent reported that these needs were unmet. A comparison by age showed that young adults aged 18-29 had greater unmet needs than those aged 30-40.

Differences Between the Child and Adult Medical Care Systems

In pediatric longitudinal studies over the last few decades, the 5-year survival rate for pediatric ALL has increased to 90 percent (Robison, 2011). Unfortunately, there has been no similar increase for adolescent and young adult ALL; currently, the overall survival rate for adults is 30-40 percent (Narayanan and Shami, 2012). Yet there is evidence that treatment in a pediatric cancer center increases survival for adolescents and young adults (De Bont et al., 2004; Peppercorn et al., 2004; Ramanujachar et al., 2006). Box 7-2 examines potential reasons for this difference. In the case of cancer treatment, it may be that the transition to adult care should be based not on age but on disease outcome, meaning that some people may need to have pediatric subspecialty care even though they have transitioned to adult primary care and taken on adult roles in other areas of life.

Like some adult providers, adult health systems are new to providing care to large numbers of young adults with serious childhood-onset diseases. Until the 1980s, for example, only childhood cystic fibrosis centers existed (Tuchman et al., 2010). Now that many more individuals with the disease are living well into adulthood, adult programs have been developing, but in many cases they are provided in the same location as pediatric programs, and adult patients often are hospitalized in pediatric settings

__________________

2 In this field, “adolescents and young adults with cancer” are typically defined as those aged 15-39 (NCI, 2014).

BOX 7-2

Caring for Young Adults with Chronic Diseases in Pediatric Versus Adult Settings

Adolescents and young adults with chronic diseases such as cancer and sickle cell disease generally have better outcomes if treated in pediatric rather than adult centers (De Bont et al., 2004; Jan et al., 2013; Peppercorn et al., 2004; Ramanujachar et al., 2006). This difference persists even when young adults are treated in the adult system using pediatric protocols. The factors that account for this difference are not yet clear, but the following may be factors: wraparound care, a developmental approach, and familiarity with the disease in pediatric care systems. The latter is especially the case with diseases such as acute lymphocytic leukemia (ALL) that can be considered pediatric diseases that either persist into adulthood or have their onset in late adolescence or young adulthood (Narayanan and Shami, 2012).

An important question is whether young adults should be kept longer in pediatric settings or changes can be made to the adult health care system. An argument for the former approach is that adult care systems are burdened with a growing elderly population and lack the resources to care for young adults. On the other hand, one could argue that keeping young adults in pediatric centers does not facilitate their being treated as adults with appropriate preventive care and confidentiality, and that adult systems are not being encouraged to develop appropriate systems of care based on a life span approach. Additional research on this question is needed.

Despite this open question, institutions are already reacting to the evidence of past poorer outcomes in adult systems by building systems within children’s hospitals to care for adolescents and young adults. Examples include the Adolescent and Young Adult Cancer Program at Seattle Children’s Hospital (Seattle Children’s Hospital, 2014) and the Adolescent and Young Adult Program at MD Anderson Children’s Cancer Hospital in Texas (MD Anderson Cancer Center, 2014).a In addition, some adult systems are creating follow-up clinics especially for those with pediatric-onset diseases. An example is the Thriving After Cancer clinic at the George Washington Cancer Institute/George Washington University Medical Faculty Associates, which provides care that addresses young adults’ needs in an appropriate adult setting (GW Cancer Institute, 2014; personal communication, September 17, 2014, April Barbour, M.D., The George Washington Medical Faculty Associates).

____________

a For additional examples of care programs for adolescents and young adults with cancer, see IOM (2013b).

(Tuchman et al., 2010). Thus the age-appropriateness of care offered for adult patients in a pediatric setting is a concern (AAP et al., 2011). In the survey by Okumura and colleagues, physicians responded that a lack of subspecialty access and having an office structure that did not facilitate coordination of care for young adults with special health care needs had

the greatest negative impact on their perceived quality of care (Okumura et al., 2010). In another study, internists saw a need to obtain the consent of young adults for family involvement in their care (Peter et al., 2009).

Studies on the perspectives of patients, providers, and families underscore the general discomfort with and lack of a structured process for the transition to adult health care (Peter et al., 2009; Reiss et al., 2005). Some pediatric providers who have developed successful relationships with patients and their families delay transitioning young adults to adult care because of “difficulty letting go,” previous experiences with difficult patient transitions, and the perception that the transfer will result in negative health outcomes (Reiss et al., 2005). An American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) survey of pediatric providers’ activities related to transition found that few offered youth and their families preparation for transitioning to an adult model of care at age 18, communicated directly with the adult provider, offered medical summaries for the youth/family and the adult provider, and/or created a medical transition plan (McManus et al., 2008). Also of note is the internist perspective that there is a need for better training in congenital and childhood-onset conditions and an urgent need for more training for adult subspecialists (Peter et al., 2009). The perspectives of patients and physicians, coupled with concern for financial support to care for these complex patients, are important factors in successful planning for transition by all concerned (Peter et al., 2009).

Efforts to Improve the Transition Process

The transition from pediatric to adult care has been identified as a problem for decades. Yet there has been minimal systematic implementation and evaluation of institutional change to address concerns about the increasing numbers of pediatric patients with chronic conditions who are now living into adulthood.

“At my age—19—my friends and I don’t even know the first thing about looking into health care services. I think that it would be very beneficial to start educating us about these things now rather than later.”

Multiple consensus studies have been published on the transition from pediatric to adult care, starting with a Surgeon’s General Conference in 1989 (AAP, 1996; AAP et al., 2002, 2011; Blum et al., 1993; Magrab and Millar, 1989). The 2011 recommendations of the AAP, American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP), and American College of Physicians (ACP) identify best practices in transitions (see Box 7-3)

BOX 7-3

Recommendations for Successful Transitions from the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP), and American College of Physicians (ACP)

AAP, AAFP, and ACP have together developed a health care transitions planning algorithm for all youth and young adults in medical home settings. The plan components are (a) assess for transition readiness, (b) plan a dynamic and longitudinal process for accomplishing realistic goals, (c) implement the plan through education of all involved parties and empowerment of the youth in areas of self-care, and (d) document progress to enable ongoing reassessment and movement of medical information to the receiving (adult care) provider. These apply to all youth and young adults, and the guidelines provide additional information for youth and young adults with special health care needs.

The document also identifies the following educational and policy recommendations for the transition from pediatric to adult health care systems:

- enhanced payment for transition services;

- case finding of those in need of transition services who are not receiving them;

- insurance coverage for patients in need of transition planning;

- standards of care and credentialing of providers;

- training for primary care physicians and medical subspecialists to promote transitions within the medical home; and

- promotion of training and clinical learning experience on transition and transfer of youth and young adults (both with and without special needs) for trainees in all medical fields.

SOURCE: AAP et al., 2011.

and state that additional elements of health care delivery and reimbursement systems are needed to achieve a successful transition (AAP et al., 2011). Recently, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) published a technical brief on transition for children with special health care needs that reiterates many of the same findings published in 1989 (McPheeters et al., 2014). Efforts also have been made to apply the Institute for Healthcare Improvement’s Triple Aim3 framework to this transition (Benson et al., 2014; Berwick et al., 2008).

__________________

3 The Institute for Healthcare Improvement’s Triple Aim framework is aimed at achieving three goals: “Improving the patient experience of care (including quality and satisfaction); improving the health of populations; and reducing the per capita cost of health care” (IHI, 2014).

Various federal agencies support transition-related activities. For example, the Got Transition initiative/Center for Health Care Transition Improvement, a cooperative agreement between the Health Resources and Services Administration’s (HRSA’s) Maternal and Child Health Bureau and the National Alliance to Advance Adolescent Health, aims to improve health care transitions by developing and expanding the use of transition materials, training the workforce, enhancing youth and parent leadership, promoting health system changes, and serving as a resource clearinghouse (The National Alliance to Advance Adolescent Health, 2014a). This initiative has developed updated recommended core elements (Six Core Elements of Transition) for pediatric, internal medicine, family medicine, and med-peds4 practices (The National Alliance to Advance Adolescent Health, 2014b):

- establishing a transition policy,

- tracking and monitoring transition progress,

- conducting transition readiness assessments,

- planning for adult care,

- transferring into adult care (if applicable), and

- integrating the young adult into an adult practice.

Materials are organized and customized for three different situations, with corresponding types of health care providers:

- transitioning youth to adult health care providers (pediatric, family medicine, and med-peds providers);

- transitioning to an adult approach to health care without changing providers (family medicine and med-peds providers); and

- integrating young adults into adult health care (internal medicine, family medicine, and med-peds providers) (The National Alliance to Advance Adolescent Health, 2014b).

These recommended core elements and available customizable tools are based on the AAP/ACP/AAFP Clinical Report (2011) and were created using the quality improvement approach outlined by the Institute for Healthcare Improvement’s change framework. This approach may set the stage for less fragmentation of care in transition, with clear guidance for coordination and communication between pediatric and adult providers, improved preparation for the transfer to adult health care, improved integration of young adults as a special population into the adult health care setting, and ways to evaluate the transition process.

__________________

4 Combined internal medicine and pediatric practice.

Similarly, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) sponsors the Emerging Adulthood Initiative. This initiative is focused on improving outcomes among adolescents and young adults with serious mental health conditions as they transition to adulthood, including transitions in health care (Georgetown University Center for Child and Human Development, 2014).

Beyond the transition issues for children with chronic medical conditions, health systems need to accommodate the needs of young adults who do not have a chronic condition but still have increased health care needs due to their stage of development and heath behaviors and the emergence of new mental and physical health conditions. The increased emergency room utilization noted above may speak to the difficulty experienced by young adults in transitioning to the adult health care system and their unmet health needs.

Behavioral Health Care Transitions

Behavioral health care systems typically are separate from medical health care systems, and include both mental health and substance abuse systems. The 1999 Surgeon General’s report on mental health describes the “de facto” mental health system as comprising four sectors (a description that applies equally well to substance abuse services): “the specialty mental health sector, the general medical/primary care sector, the human services sector, and the voluntary support network sector” (HHS, 1999, p. 73).

Funding of this de facto system generally is split between public/government sources (e.g., Medicaid, Medicare, state funding) and private sources (including services provided through private funding and services provided directly by private agencies, such as employer-provided insurance) (HHS, 1999). Behavioral health services may be office based (typically 1-6 hours/week), home based (usually more intensive than office-based treatment), intensive outpatient (in which clients sleep at home but receive treatment for several hours per day), residential/inpatient, and intensive inpatient (which includes more extensive medical care, typically for a relatively brief period of time). Until recently, private insurance often limited payment for treatment to a restrictive amount that was easily exceeded by more serious treatment needs. Individuals then either paid out of pocket or applied to the public sector for services (HHS, 1999).

The Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act, enacted in 2008, targets reducing the large disparity in insurance coverage for behavioral and physical health treatment. The legislation requires insurance groups to provide the same level of benefits they provide for general medical treatment for mental health or substance use disorders. Under final rules for this act, effective July 1, 2014, deductibles for behavioral health must be on par with

those for similar services for other medical conditions, and treatment limits or co-pays more restrictive than those for medical/surgical services are prohibited. Standards for reimbursement for psychosocial treatments also are being discussed, and the Institute of Medicine (IOM) has been asked to conduct a study to develop a framework for establishing efficacy standards for psychosocial interventions used to treat mental disorders; the results of these discussions will have important implications for young adults (Insel, 2014; IOM, 2014). In addition, the ACA now prohibits lifetime or annual dollar limits for essential health benefits, which include mental health and substance abuse care (CMS, 2014a). Future research examining the impact of these new rules and requirements will help determine the extent to which needed behavioral health care is more affordable and accessible to young adults.

Aging Out of Child-Serving Systems

For young adults with mental health or substance use treatment needs, an additional factor that complicates service delivery is the many funding streams, state-funded services, and ways of organizing treatment that are age defined (Davis et al., 2009). Age-defined services and systems include special education (ending at age 21), foster care (typically ending at age 18 or 21), juvenile justice (typically ending at age 17 or 18), and adult criminal justice (starting at ages 16, 17, or 18). Public mental health systems also are typically divided organizationally and fiscally between child and adult services (Davis, 2003; Davis et al., 2006). Each of these systems may provide or coordinate behavioral health services. Thus, young adulthood marks an age when particularly vulnerable individuals’ behavioral health services are disrupted by “aging out” of children’s service systems. Continuity of care as individuals age out is dependent on access and strong connections to behavioral health services from adult systems. In addition, within public mental health services, policies that define eligibility criteria or target populations for services are distinctly different for child and adult mental health (Davis and Koroloff, 2006), with adult criteria typically being more narrow. This produces a barrier to access based on changing age, not changing need.

“It took me about 6 months to get an intake appointment. My psychologist left after 2 months.”

Another factor that contributes to discontinuities in care for any young adult with health care needs is the age-based eligibility criteria for Medicaid

and Supplemental Security Income (SSI).5 Medicaid has different eligibility criteria for children (dependent members of a household) and adults. Those who age out can fail to meet the adult criteria (Pullman et al., 2010). Qualifying for Medicaid by meeting the Social Security Administration’s (SSA’s) definition of disability also is impacted by age-based definitions of “disability” (e.g., ADHD is a qualifying mental disorder for children but not for adults). According to SSA, each year tens of thousands of child SSI recipients reach age 18, and their medical eligibility is redetermined according to adult disability standards (Hemmeter, 2012). Overall, about one-third of these children (37 percent) lose eligibility (Hemmeter, 2012). Among youth with mental health disorders that fall under the “other mental disorders” category (e.g., anxiety, affective, and disruptive behavior disorders)—who make up 28 percent of all children receiving SSI after reaching age 18—more than half (53 percent) lose eligibility upon redetermination (Hemmeter, 2012). Overall, these age-based criteria contribute to higher risk of Medicaid disenrollment during young adulthood, even among highly vulnerable clinical populations (Davis et al., 2014; Pullman et al., 2010), and may contribute to reduced access to needed behavioral health care (Slade et al., 2014). Although discussed here in the context of behavioral health transitions, many of these same discontinuities apply more generally to health care coverage issues for young adults.

Differences Between Child and Adult Mental Health Systems

Several typical treatment culture differences characterize child and adult mental health systems. The first is the manner in which parental figures are involved. In their seminal work defining system-of-care principles for children with emotional disturbance, Stroul and Friedman (1986) focus on the importance of partnering with parents to provide appropriate treatment and supports for their child. Since that work was published, child mental health systems have largely changed to work more closely with parental figures in developing and implementing treatment and service plans for their children (Stroul, 2002). Approaches such as the wraparound process (VanDenBerg and Grealish, 1996) and multisystemic therapy (Henggeler et al., 1998) are formalized means of partnering with family members to address the child’s mental health condition and resulting functional impairments. However, family involvement is less emphasized in adult mental health systems, and once they turn 18, youth can legally restrict providers from sharing any treatment information with family members. Yet client factors that facilitate shared decision making often are still immature in the

__________________

5 In most states, SSI beneficiaries are automatically eligible for Medicaid, while other states require a separate application and determination of eligibility (SSA, 2014).

youngest adults (Delman, 2012; Joseph-William et al., 2014). Given the unique role parents can play in the lives of young adults (as described in Chapter 3) and the help they could provide with decision making, excluding their potential supports may compromise the efficacy of treatment for a young adult needing behavioral health services. Indeed, family cognitive-behavioral treatment appears to be an important component of early intervention in psychosis (Gleeson et al., 2009).

Another substantial difference in practice between child and adult mental health systems is related to care coordination. Children with serious mental health conditions often are involved in multiple systems, including child welfare, juvenile justice, special education, and mental health. Providers in these systems typically are aware of the involvement of other systems, and often communicate and coordinate with them. Adult mental health, by contrast, is often insular, so that services such as vocational rehabilitation or drug treatment are provided within the mental health system rather than in partnership with those systems (Davis et al., 2012b). Disconnects in cross-system connections, especially between child and adult systems, can cause disruptions or redundancies in services, especially for 18- to 21-year-olds who are still involved in child systems.

Finally, adult mental health systems often fail to recognize the unique needs of young adults, and there are few interventions with strong evidence of efficacy for this age group (GAO, 2008). With the exception of interventions to treat early psychosis, few interventions have been devised specifically for this age group, and all are in early stages of development (Davis, 2012a). Evidence of the efficacy of evidence-based adult or child interventions with a young adult population is limited (Davis et al., 2012a). Clinical trials including this age group as part of a larger age group (e.g., studies of adults in general) cannot sufficiently establish efficacy in the young adult population. For an age effect to be detected, a large sample size of the young adult age group is needed, and few age group comparisons have been conducted thus far in published studies. However, some studies have reported significant differences in outcomes or relative effectiveness of psychosocial interventions between older and younger age groups (e.g., Burke-Miller et al., 2012; Haddock et al., 2006; Kaplan et al., 2012; Rice et al., 1993). Applying interventions that have been established in older or younger populations and adapting those interventions for young adults is a reasonable starting point for research and service provision. For example, the individual placement and support model for adults with severe mental illness (Bond, 1998) has been adapted and tested for use with young adults with first or early episodes of psychosis (Killackey et al., 2008; Major et al., 2010; Porteous and Waghorn, 2007), with results providing support for its use in this age group.

Substance Abuse Care Transitions

Many of the issues of transition faced by young adults with mental health conditions are also faced by those with substance use disorders: involvement in multiple child systems that end variably between ages 18 and 21, adolescent and adult treatment providers who are trained to work with one but not the other age group, stricter diagnostic criteria for adult than child Medicaid coverage for substance abuse-based eligibility, and few interventions with efficacy for reducing substance use specifically in young adults. Several of the unique aspects of the substance use system are worth noting, however. Foremost is the heightened stigma of substance abuse problems. Most substance use is illegal, and alcohol use is illegal for young adults under age 21. Recreational use of marijuana also is illegal except in Washington and Colorado for those over the age of 21. Moreover, use of substances often is seen as a moral issue, and problematic substance use is viewed as a volitional problem rather than a chronic illness. The legal issues and moral values have two major consequences—reducing funding for treatment and posing a barrier to treatment seeking (Cutcliffe and Saadeh, 2014; Drucker, 2012). The result is a scarcity of substance abuse services and long wait lists for those services.

Brief substance use treatments for which there is growing evidence of efficacy are increasingly available on college campuses, but for the many young adults with substance use problems that are not in college or the military, or for college students whose substance abuse problems require more than brief treatment, the challenge of finding a provider after the significant step of acknowledging the need for help is a formidable barrier to care. The scarcity of treatment resources, in combination with the need for young adults to advocate on their own behalf despite their inexperience in doing so, can lead to a large unmet need for treatment in this age group (Tighe and Saxe, 2006). Mental health and substance use disorders can further impede young adults’ abilities to advocate for themselves. Young adults’ inexperience with self-advocacy also means that simply providing them with information about how and where to obtain health insurance or care, while important, is not sufficient. Also necessary are active and effective preparation of adolescents and young adults and outreach by the health care system to help them access and complete needed treatment.

PREVENTIVE CARE FOR YOUNG ADULTS

The majority of health problems during young adulthood are preventable, and behaviors associated with negative health outcomes have high prevalence among young adults, as described in Chapter 6. These behaviors often are also responsible for the onset of many chronic health conditions

(e.g., obesity, diabetes, addiction to substances, mental health disorders) that lead not only to functional impairment throughout adulthood but also to a shortened life span. Many of these behaviors represent an opportunity for cessation of harmful behaviors, the development of healthy alternatives, or further entrenchment of the behaviors that threaten adult health.

Use of Preventive Care in Young Adults

Knowledge of the use and delivery of preventive services for young adults is limited by the lack of attention to this age group in clinical delivery systems and health services research noted throughout this report. A few recent studies, either population-based assessments or based within health care delivery systems, have documented the relatively low rates of preventive services in this population (Fortuna et al., 2009; Lau et al., 2013b; see Table 7-3). Considerable variation is related to gender, race/ethnicity, and having a usual source of care. With the exception of influenza vaccination, young females are more likely than males to receive preventive services (Lau et al., 2013b). Young adults who have a source of care they typically use also are more likely to receive preventive services. Black young adults are more likely than their white counterparts to receive the full range of sexually transmitted infection (STI), cholesterol, and diet counseling (Lau et al., 2013b). Compared with whites, Asians are less likely to receive STI

TABLE 7-3 Percentage of Visits During Which Preventive Counseling Was Provided to Young Adults (aged 20-29), 1996-2006

| All Specialties (%) | Primary Care (%) | Ob/Gyn (%) | |

| Any | 30.6 | 32.7 | 33.6 |

| Injurya | 2.4 | 3.1 | 0.8 |

| Smoking | 3.1 | 4.2 | 3.1 |

| Exercise | 8.2 | 9.4 | 8.2 |

| Weight reductionb | 3.0 | 3.8 | 3.4 |

| Mental health | 4.1 | 4.2 | 1.3 |

| STI/HIVc | 2.7 | 2.6 | 7.1 |

NOTES: “Mental health” does not include substance abuse or use; STI = sexually transmitted infection.

Primary care includes internal medicine, pediatrics, family practice, general practice, general preventive medicine, or public health or general preventive medicine.

a Data were available for 1996-2000 and 2005-2006.

b Data were available for 2001-2006.

c Data were available for 1996-2000.

SOURCE: Adapted from Fortuna et al., 2009.

TABLE 7-4 Past-Year Receipt of Screening or Preventive Services Among Young Adults Aged 18-25 Who Had a Past-Year Visit, National Health Interview Survey, 2011

| Blood Pressure Check | Fasting Blood Sugar Check | Talked About Diet | Talked About Smoking If a Smoker | Pap Screen for Women | Flu Shot | |

| % Who received screening or preventive service | 87.3 | 22.3 | 22.8 | 52.0 | 66.5 | 26.2 |

SOURCE: Analysis done by Sally H. Adams @ University of California, San Francisco, Division of Adolescent & Young Adult Medicine.

and emotional health screening, and Latinos/as are more likely to receive cholesterol and diet counseling (Lau et al., 2013b).

Analysis of National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) data from 2011 reveals that among young adults who had a clinical visit during the past year, access to a range of preventive services ranged in frequency from 87 percent receiving a blood pressure check to 22 percent receiving a fasting blood sugar check (see Table 7-4). It is important to note that such preventive screening can take place during any clinical encounter with a provider or in alternative delivery systems (e.g., pharmacies, work or school sites). Providers need to be encouraged to use any visit as an opportunity to address a component of preventive care.

Guidelines for Preventive Care for Young Adults

This section examines existing guidelines, their implementation, and monitoring of adherence.

Existing Guidelines

There continue to be no specific medical, behavioral, or oral health guidelines focused specifically on the young adult population. The clinical preventive services recommendations6 of the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) consist of evidence-based recommendations across several specific health areas. For the past two decades, there has been a strong movement toward developing consensus-based guidelines for care for adolescents, starting with the American Medical Association’s Guidelines for

__________________

6 See http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/recommendations.htm for details (accessed October 22, 2014).

Adolescent Preventive Services: Recommendations and Rationale (Elster and Kuznets, 1994) and Bright Futures: Guidelines for Health Supervision of Infants, Children, and Adolescents (Green, 1994). The most recent Bright Futures edition includes preventive care recommendations up to age 21 (Hagan et al., 2008). A revision of Bright Futures is expected to be released in 2015.

Several groups have called for the development of care guidelines for young adults (Callahan and Cooper, 2010; Fortuna et al., 2009; Irwin, 2010; Ozer et al., 2012). Recently, Ozer and colleagues (2012) conducted an analysis to identify evidence-based guidelines for young adults by reviewing professional consensus guidelines and the evidence-based guidelines from the USPSTF that include young adults (aged 18-26). They found that four groups—AAP, the American Congress of Gynecologists and Obstetricians (ACOG), AAFP, and ACP—had developed guidelines relevant to young adults.

“Most young adults don’t want to pay for anything if they can, so even though preventive care is for your benefit and you can access it at any time, some people don’t realize that that is the case. They think they may not be covered and may have to pay for services.”

Increasingly, health care plans have incorporated an annual preventive care visit with limited or no co-pays as part of the core benefits for subscribers. The ACA has expanded the opportunity for young adults to receive an annual preventive visit with no associated co-payments, and a recent study documents an increase in young adults’ receipt of a general checkup in the first year of implementation of the ACA—48 percent in 2011 as compared with 44 percent in 2009 (Lau et al., 2014b). Table 7-5, adapted from Ozer et al. (2012), lists the preventive services that most private plans must cover under the ACA, which include the evidence-based screening and counseling services rated highly in either Category A or B by the USPSTF,7 the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices’ recommended immunizations, the Bright Futures recommendations, and the services specified in the Women’s Preventive Services Guidelines (HHS, 2012). The Women’s Preventive Services Guidelines (HRSA, 2014; IOM, 2011) specify that in addition to the services provided for all adults, the services

__________________

7 The USPSTF defines Category A as follows: “The USPSTF recommends the service. There is high certainty that the net benefit is substantial.” Category B is defined as follows: “The USPSTF recommends the service. There is high certainty that the net benefit is moderate or there is moderate certainty that the net benefit is moderate to substantial” (USPSTF, 2012).

TABLE 7-5 Preventive Health Care Services for Young Adults (aged 18-26) Covered Under the Affordable Care Act

| Services Covered for All Young Adults (ages 18-26) | Additional Services Covered for Young Adults Ages 18-21 | Additional Services Covered for Women (ages 18-26) |

|

Alcohol misuse screening and counseling Tobacco use screening Blood pressure screening Diabetes (Type 2) screening for those with high blood pressure* Diet counseling* Obesity screening and counseling Cholesterol screening* Depression screening HIV screening STI prevention counseling* Syphilis screening* Immunizations Hepatitis A Hepatitis B Human papillomavirus Influenza Measles, mumps, rubella Meningococcal Pneumococcal Tetanus, diphtheria, pertussis Varicella |

Annual wellness visit Screening and counseling for illicit drugs Suicide screening Safety/violence screening Family/partner violence (male and female) Fighting Use of helmets Use of seat belts Driving under the influence Use of firearms Bullying Polio immunization |

Well-woman visits Contraception Folic acid supplements Domestic and interpersonal violence screening and counseling (women of all ages) Cervical cancer screening (if sexually active) Chlamydia infection screening Gonorrhea screening* Breast cancer genetic test counseling (BRCA)* Breast cancer chemoprevention counseling* Hepatitis B screening for pregnant women Rh incompatibility screening for pregnant women Anemia screening for pregnant women Gestational diabetes screening Urinary tract or other infection screening for pregnant women Comprehensive support and counseling for breastfeeding |

* If at higher risk.

NOTE: STI = sexually transmitted infection.

SOURCES: Adapted from Ozer et al., 2012, 2013. Original sources are the evidence-based screening and counseling services rated highly either in Category A or B by the USPSTF, immunizations recommended by the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, the Bright Futures recommendations, and the services specified in the Women’s Preventive Services Guidelines.

listed in Table 7-5 must be provided to women by private plans without cost sharing (Armstrong, 2012a,b; HHS, 2012; HRSA, 2014). Note that Table 7-5 summarizes what evidence-based services are currently covered, and does not provide a comprehensive list of what this committee deems should be covered.

Comprehensive dental guidelines for young adults could not be identified, although the American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry recommends

that a dental home be established when the adolescent patient, family, and dentist agree that it is time to transition to adult dental care (AAPD, 2013).

Implementation of Guidelines

Multiple approaches can be used to incorporate preventive guidelines into clinical practice for young adults. At present, however, there is no consensus among health professional organizations, the USPSTF, health care plans, and state and federal agencies on guidelines that should be used as the starting point for implementation.

Barriers that impede the delivery of preventive services in clinical settings include both clinician factors (e.g., lack of knowledge of guidelines; attitudes toward the efficacy of preventive services; and lack of training, skills, and confidence to deliver the services) and external factors (e.g., time constraints, lack of screening tools, lack of reimbursement) (e.g., Ozer et al., 2005). Efforts comparable to those over the past two decades to increase the delivery of preventive services to adolescents are just beginning for young adults. Multiple models shown to increase preventive screening in adolescents could be adapted for use for young adults (Boekeloo and Griffin, 2007; Boekeloo et al., 2003; Klein et al., 2003; Olson et al., 2009; Ozer, 2007; Ozer et al., 2005; Sanci et al., 2012; Stevens et al., 2008; Tylee et al., 2007).

Monitoring of Adherence to Guidelines for Young Adult Preventive Care

No mechanisms for monitoring adherence to guidelines relevant to young adult preventive care currently exist. With the implementation of preventive care under the ACA, it will be necessary to identify national- and state-level datasets that can be used to monitor the implementation of these guidelines. Monitoring guideline adherence for young adult preventive care is important in both the public health and health care domains. Below are identified existing datasets that could be used for this purpose and describe associated challenges.

Four nationally representative ongoing surveys that include some measures of preventive screening and counseling for adults in general can be accessed to obtain estimates specifically for young adults: the NHIS, a survey of health status and health care access; the Medical Expenditures Panel Survey (MEPS), a household survey of health, health care, and health care expenditures; the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey, which monitors the services patients receive from clinicians in ambulatory settings; and the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, a survey of behavioral risk factors associated with major morbidity and mortality (AHRQ, 2014; CDC, 2014a,b,c). In addition, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Ser-

vices (CMS) is developing and implementing a revised set of adult health care quality measures in conjunction with AHRQ (CMS, 2014e; GPO, 2012; Mann, 2012). Many of these measures are applicable to young adults (e.g., influenza vaccinations, body mass index assessment, screening for clinical depression) and will be of use in assessing the implementation of clinical preventive screening in Medicaid-enrolled young adults. The use of these measures is encouraged by CMS but is optional for the states. It is not clear how states will choose the measures on which they will report and what capability they will have to access data specific to young adults.

Despite the availability of these data, researchers, policy makers, funders, and other stakeholders need to have the expertise to break out the specific ages that make up young adulthood, examine state-level data, and differentiate specific subpopulations. Moreover, some of these datasets are more readily accessible than others. In many cases, online analysis can be carried out, but there usually are restrictions on the specificity of age groups and the breadth of subgroup analyses possible. In addition, most national survey data centers allow analysis of state-level data upon request, but the datasets are not always sufficiently large to study the states with smaller populations.

For both national- and state-level data analysis, data elements that help differentiate special populations may be insufficient. Gaps may exist for youth who have been in foster care or were recently homeless or incarcerated. For the CMS data, only young adults enrolled in Medicaid will be able to be assessed with the new adult core measures.

Some of the survey procedures also may introduce bias into the survey responses. For example, the MEPS data collection procedures identify the adult respondent for the entire household, including young adults, as the adult who is most knowledgeable about the health care utilization and expenditures of all household members (AHRQ, 2014). For many young adults, parents may be unaware of health care accessed confidentially; through college health services; or through other systems of care, such as public health clinics and pharmacies (Lau et al., 2014a).

In addition, current adult health care monitoring efforts do not cover many key topics relevant to young adult screening and counseling, such as obesity-related issues, substance use, and reproductive health issues. When these topics are assessed, a lack of specificity often limits the utility of the assessment. For example, the USPSTF recommends that young adults have their blood pressure screened every 2 years when it is is below 120/80 mm Hg (NAHIC, 2014). Yet surveys such as the NHIS asking about the recency of blood pressure monitoring do not always ask respondents to report their blood pressure, so adherence to this guideline cannot be determined.

Preventive Care for Behavioral Health Conditions

There are fewer rigorously tested approaches for preventing behavioral health disorders than exist for many physical disorders (e.g., encouraging diet or exercise in all patients to reduce the likelihood of their developing cardiovascular disease). One example of an accessible behavioral health prevention approach is encouraging aerobic physical activity to prevent the development of depression (Mammen and Faulkner, 2013).

Most prevention approaches for behavioral health target children and adolescents based on the young ages at which many behavioral health conditions develop and the ready access to these populations in schools (IOM, 1994; Stice et al., 2009). Studies of prevention interventions for conditions common to young adults—including Web-based technologies to reduce the risk of developing depression (Van Voorhees et al., 2011) and anxiety (Braithwaite and Fincham, 2007; Christensen et al., 2010; Cukrowicz and Joiner, 2007)—have targeted primarily college students. SAMHSA funds the Campus Suicide Prevention Grants8 to support efforts at postsecondary institutions to prevent suicide and to improve services for students with problems that put them at risk of suicide, such as depression, substance abuse, and other behavioral health issues; however, there are currently no rigorously tested interventions to implement. A growing body of research documents brief interventions for reducing college binge drinking with some evidence of efficacy (e.g., Kulesza et al., 2013). Preliminary evidence also suggests that parents who talk with their children about binge drinking before they depart for college can decrease excessive drinking and alter drinking perceptions (Turrisi et al., 2001).

Instead of going to college, some young adults enter the military after high school. As discussed in Chapter 5, military personnel who have been deployed are at heightened risk of developing posttraumatic stress disorder and other mood and anxiety disorders and for suicide. While several interventions have been developed for use both before and during deployment to prevent the development of posttraumatic stress disorder or suicide, none have as yet been rigorously tested (Hoge and Castro, 2012; Hourani et al., 2011). Predeployment mental health screening also has been used to either divert some individuals from deployment or provide additional mental health support (mainly medication) during deployment (Warner et al., 2011). There is evidence of reduced mental health needs in brigades with screening compared with those without (Warner et al., 2011).

For civilian young adults not enrolled in college or in colleges that offer some preventive interventions, most interventions are designed for

__________________

8 See http://www.samhsa.gov/grants/2013/sm-13-009.aspx for details (accessed October 22, 2014).

individuals at high risk of developing a mental health disorder or with conditions that increase this risk. For example, cognitive-behavioral interventions can reduce the risk of developing posttraumatic stress disorder if administered within days or weeks after a traumatic event (Agorastos et al., 2011). Given the high risk of violent victimization in young adulthood, including sexual violence and witnessing violence, prevention of trauma symptoms and posttraumatic stress disorder is particularly relevant in this age group.

The experience of psychological stress is pervasive in young adults and may contribute to the subsequent development of behavioral or physical health disorders, as described in Chapter 6. A variety of stress reduction techniques are available for which there is evidence of efficacy in adults, such as mindfulness-based approaches or cognitive therapy (Abbott et al., 2014; Querstret and Cropley, 2013), cognitive-behavioral techniques (Cruess et al., 1999), and relaxation techniques (Shah et al., 2014). Some of these techniques can reduce symptoms of behavioral health conditions (Chiesa and Serretti, 2014; Khoury et al., 2013; Shah et al., 2014), although findings on the benefits for physical conditions are more mixed (Abbott et al., 2014; Fordham et al., 2013; Hughes et al., 2013; Lauche et al., 2013; Reiner et al., 2013). As with other behavioral health interventions, direct evidence of the efficacy of these stress reduction approaches specifically in young adults is limited, and studies have focused primarily on college students (Bodenlos et al., 2013; Tanis, 2012).

There are also approaches for reducing the development of depression in high-risk groups, such as adolescent children of parents with depression or adolescents with elevated depression symptoms (Beardslee et al., 2013; Clarke et al., 1995, 2001). One such approach has been adapted for Web-based intervention and has shown moderate effects in young adults (Clarke et al., 2009). In addition, pharmacological treatment combined with psychotherapy reduces the likelihood of suicide in individuals who have unipolar or bipolar affective disorders (Rihmer and Gonda, 2013). And since young adulthood is a common age for becoming a parent, preventing postpartum depression is particularly relevant in this age group. While cognitive-behavioral therapies reduce postpartum depression, evidence is currently insufficient regarding approaches for identifying those at risk and providing preventive interventions (Nardi et al., 2012).

Finally, because young adulthood is the peak age of onset of psychosis (Copeland et al., 2011), prevention of these most serious mental illnesses is a high priority. There is growing evidence that cognitive-behavioral therapies and complex psychotherapies can delay the transition from symptoms indicating high risk of developing psychosis to the development of a psychotic disorder, while pharmacotherapy does not appear to be beneficial for this purpose (Stafford et al., 2013). Both psychotherapies and pharma-

cotherapies can, however, help reduce the likelihood of a second episode of psychotic illness in those who have recently experienced a first episode (Álvarez-Jiménez et al., 2011).

BEHAVIORAL HEALTH INTERVENTIONS FOR YOUNG ADULTS

Effective behavioral health treatments and strategies exist for adults. The efficacy of these treatments specifically for young adults, however, is largely undemonstrated because they typically group young and other adults together (Davis et al., 2012a).

Pharmacological interventions are expected to be as efficacious in young as in older adults, although noncompliance may be greater in young adults (Baillargeon et al., 2000; Kessing et al., 2007). Psychosocial interventions, however, cannot be assumed to be as efficacious in young as in older adults, as they can be influenced by many of the factors that are changing or less mature in young compared with older adults. Such factors include responsibility taking, response to authoritative figures, changing roles within the family, and responses to behavioral contingencies. Indeed, young and older adults even perceive various qualities of their interaction with physicians differently (Bradley et al., 2001). Consequently, psychosocial interventions need to be explicitly tested in young adults. To this end, the young adult sample size needs to be large enough to detect an age effect compared with older or younger age groups (Davis et al., 2012a). Few published studies have compared age groups, although some have yielded significant findings comparing young and older adults with respect to outcomes or the effiacy of psychosocial interventions (e.g., Burke-Miller et al., 2012; Haddock et al., 2006; Kaplan et al., 2012; Rice et al., 1993; Sinha et al., 2003). With the exception of interventions to treat early psychosis, few interventions have been developed specifically for young adults; all are in early stages of development, and there are few for which efficacy has been demonstrated in this age group.

HEALTH CARE COVERAGE FOR YOUNG ADULTS

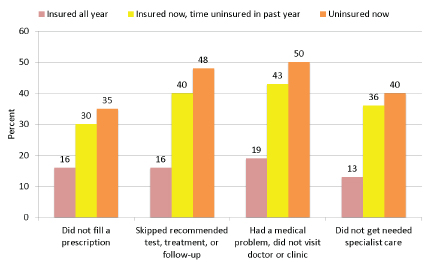

Young adults without health insurance or with gaps in insurance coverage are less likely to access health services compared with young adults who are continuously insured (see Figure 7-1). Health insurance coverage rates for young adults, however, have historically been the lowest of any age group. In 2010 and 2011, for example, young adults aged 19-25 had an uninsured rate of 28 percent and were the age group most likely to be uninsured (Todd and Sommers, 2012). The rate of uninsurance among empoyed young adults also is one-third higher than that among older

FIGURE 7-1 Percentage of young adults aged 19-29 who experienced different types of health care access problems in the past year because of cost (2010 data).

SOURCE: Collins et al., 2012.

employed adults because the part-time, entry-level, seasonal, and small-business jobs held more commonly by young versus older adults often do not include health benefits (CMS, 2014d).

In this section, we describe state-level efforts to enhance coverage for young adults and the impact of the ACA on this population. We also discuss several groups of young adults who have particular difficulty accessing care, including unauthorized immigrants, those exiting the foster care system, those involved in the justice system, and those with mental illness. The focus is primarily on financial barriers, but we identify additional barriers as well. It is important to keep in mind that access to adult care that fails to effectively engage and retain young adults or address their particular needs also is insufficient. A recent study showed that even though young adults’ coverage increased following en-

“My boss took the time to discuss general health care information with me, which helped me understand my choices better.”

actment of the ACA, the impact on their health status and the care they received was limited (Kotogal et al., 2014), although their use of emergency departments for care does appear to have decreased (Hernandez-Boussard et al., 2014).

State-Level Efforts to Improve Young Adults’ Health Care Coverage