Government Investments in Marginalized Young Adults

Key Findings

- Marginalized young adults—such as those living in poverty, those aging out of foster care, those in the justice system, those with disabilities, and young parents—are much less likely than other young adults to experience a successful transition to adulthood, although many of these young people ultimately fare very well as adults, and their hopes and aspirations are similar to those of young people who have not been marginalized. Meeting the needs of marginalized young adults not only improves their lives, but also has the potential to help them become fully contributing members of society.

- Although marginalized young adults are a heterogeneous group, they often share a number of characteristics and experiences, such as low income and behavioral health problems. Similarly, there is considerable overlap in the populations targeted by the many programs that serve marginalized young adults.

- A comprehensive view of populations of marginalized young adults is lacking, which limits the development of policies and programs intended to reduce their marginalization.

- Fragmented programs have narrow and idiosyncratic eligibility criteria that pose obstacles to young adults’ getting the help

-

they need, often create lapses in help when it is provided, and too often are stigmatizing. Major entitlement programs intended to help vulnerable populations provide limited support for young adults, and discretionary programs targeting these populations often fall far short of meeting demonstrable need.

- Variations in the categorization of marginalized young adults across programs result in a lack of accountability, with multiple distinct outputs and outcomes being associated with the plethora of programs. There is no collective accountability for improving the overall health and well-being of marginalized young adults.

While the transition to adulthood can be challenging for anyone, some young people are particularly vulnerable to experiencing difficulty during this period. This vulnerability can be manifest as individual or group characteristics that serve as risk factors for a poor transition to adulthood in one or more areas of health and well-being. For example, prior chapters of this report have illustrated how living in poverty, being a single parent, or having a disability all increase the likelihood that a young adult’s health and well-being will suffer. Concern about the risks posed by these individual characteristics has led to the creation and evolution of various government-supported programs. Many of these programs are intended to serve populations perceived as needing help beyond what is available from their families and communities, while some are more focused on controlling the behavior of those perceived to be a threat to others. In many cases, these programs do not serve all of their target populations. Some, such as foster care or the corrections system, are what might be called custodial systems, but most are not.

“We need to encourage professionals to not only open doors for their children, but open doors for young people in marginalized communities.”*

We refer to young people who exhibit characteristics that put them at risk for poor outcomes during young adulthood as marginalized young adults, whether or not they are currently served by government programs. Our use of this term is informed by the concept of social exclusion, a concept

__________________

* Quotations are from members of the young adult advisory group during their discussions with the committee.

denoting the economic, social, political, racial and ethnic, and cultural marginalization experienced by specific groups of people because of social forces such as poverty, discrimination, violence and trauma, disenfranchisement, and dislocation (Daly and Silver, 2008; Mathiesen et al., 2008; Sen, 2000). Commitment to social inclusion is based on the belief that a democratic society benefits when all its members participate fully in community affairs. Viewing marginalized populations through this lens helps shift the focus from individuals’ difficulties or limitations to how society portrays and treats them. An emphasis on social inclusion calls for the identification of policies that exclude certain groups from full participation in society and the development of policies that enhance opportunities for full participation. We believe social exclusion is a useful lens through which to view how policies contribute to or ameliorate the relatively poor outcomes experienced by the groups of young people on which we focus here.

In this chapter, we describe selected programs that serve marginalized young adults and what is known about the populations they serve. We summarize evidence for the effectiveness of these programs and the services they fund and make recommendations regarding policies and research that could improve the prospects of marginalized young adults. In some cases (e.g., foster care, homeless youth programs), these programs explicitly target young adults as a distinct population in need of special assistance; other programs (e.g., Temporary Assistance for Needy Families [TANF], the criminal justice system) serve large numbers of young adults but generally do not distinguish them from older adults. Available evidence suggests that on average, marginalized young adults are much less likely than other young adults to experience a successful transition to adulthood. Nonetheless, it is important to keep in mind that many of these young people ultimately fare very well as adults. Moreover, their hopes and aspirations are similar to those of young people who have not been marginalized. We believe they should be seen as young people who could potentially benefit greatly from supportive policies, and that everyone would benefit from their full participation in society.

“No longer depending on welfare, finding a job, and breaking through the system and living above it is what I define as success.”

We do not attempt here to describe every population that might be considered vulnerable or to provide an exhaustive review of federal programs for young people likely to experience a challenging transition to adulthood. Most notably, while we do not focus explicitly here on poverty

and racial discrimination, it should be clear from prior chapters of this report and from the demographic makeup of the populations described in this chapter that these factors are central to the marginalization of many young adults. Young adults with disabilities also are among the marginalized populations of young adults; they are discussed at length in Chapters 4 and 7, and therefore are not examined here in detail. Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) young adults may also be marginalized in certain circumstances, but are not addressed in depth here because they are not targeted by any federal programs. Nevertheless, while it is difficult to obtain reliable estimates, research indicates that these young people likely are overrepresented in some of the programs discussed here (e.g., services for the homeless, the criminal justice system, and foster care) and experience poorer outcomes in these programs than heterosexual young adults (Courtney et al., 2011; Dworsky, 2013; Hanssens et al., 2014; Wilson et al., 2014).

“Programs and services should provide help in a way that aims to understand the person, the whole person—their interests and strengths as well as areas for improvement.”

Our choices for discussion in this chapter are intended to highlight the following kinds of populations and programs:

- marginalized populations that include a relatively large number of young adults;

- marginalized populations that are the target of relatively large government investments; and

- programs that help illustrate important between-program distinctions (e.g., between entitlement programs and those with annual appropriations, between federally administered programs and those left largely to state and local administration).

We focus on the following populations:

- young adults aging out of foster care,

- young adults in the justice system,

- homeless young adults,

- young parents, and

- young unauthorized immigrants.

For each of these populations, we describe their characteristics, programs intended to help address their needs, and available evidence for program effectiveness.

Next we examine common characteristics of the programs included in this review and the populations they serve, and the implications for improving the health and well-being of young adults. Of particular note is the overlap of populations served by these programs and the frequency with which the young people they serve exhibit characteristics that can imperil a successful transition to adulthood (e.g., poverty, early parenting, mental health conditions, limited education, poor social support). We then look at evidence for assisting marginalized young adults. The final section presents conclusions and recommendations.

YOUNG ADULTS AGING OUT OF FOSTER CARE

An understanding of the conditions of young people transitioning out of foster care to adulthood requires an understanding of the overall purposes of the foster care system.1 State child welfare programs are operated under federal policies found in Titles IV-B and IV-E of the Social Security Act, with Title IV-E providing federal reimbursement to states for a significant portion of the costs for children in foster care (SSA, 2014).2 Juvenile and family courts supervise state and local public child welfare agencies’ care of children. Children enter foster care after determination from a public child welfare agency, generally with the approval of the court, that removal from the home will protect them from abuse, neglect, and/or dependency.3

The vast majority of children who enter foster care will exit into legally “permanent” placements; of the estimated 240,923 children leaving out-of-home care in the United States during fiscal year (FY) 2012, 87 percent left to live with family, were adopted, or were placed with a legal guardian (ACF, 2013c). Two percent of children were transferred to a different public agency (e.g., a probation or mental health department), and 1 percent ran away and were discharged from foster care.

Despite child welfare agencies’ efforts to identify permanent homes for those in foster care, some become “emancipated” to “independent liv-

__________________

1 Consistent with its use in federal policy, the term “foster care” is used here to describe out-of-home care provided by government for abused and neglected children and youth. Foster care includes family foster care, kinship foster care, and group care placement settings.

2 States receive reimbursement for a portion of payments to foster care providers and allowable administrative costs.

3 While short-term emergency placements can be made by child welfare agencies prior to court review, child welfare agencies must obtain court approval to place children against their parents’ will for more than a few days.

ing,” usually upon turning 18 or achieving a high school diploma.4 This is known as as “aging out of foster care.” Recent changes in federal law allow states to claim reimbursement for foster care up to age 21, but in most states youth may not remain in foster care much beyond their 18th birthday (NRCYD, 2014). Data provided to the federal government by states show that 23,396 youth (10 percent of all exits) were discharged from foster care to independent living in 2012, although it is unclear from the data how many youth entered independent living voluntarily versus those who were involuntarily discharged because of their age (ACF, 2013c). The data also do not include the number of youth who leave foster care without permission from the child welfare agency and court as they near the age of discharge (i.e., runaways). Anecdotal evidence suggests that some young people labeled as runaways exit foster care for this reason, and some approaching the age of discharge leave care without agency approval to live with members of their family of origin and are recorded in state data systems as “reunified” with their family rather than having aged out of foster care.

Relatively few young people who age out of foster care spent the majority of their childhood in care. A study that examined the placement experiences of youth in foster care on their 16th birthday found that the majority entered care after turning 15, and only 10 percent entered care at age 12 or younger (Wulczyn and Brunner Hislop, 2001); 47 percent of the youth in the study were returned to their families. More youth experienced “other” exits (21 percent, mainly transfers to other child-serving systems, e.g., the juvenile justice system) or ran away from care (19 percent), compared with the 12 percent who aged out.

In summary, the majority of older youth in foster care entered during adolescence, and comparatively few remain in care until officially aging out. Those who do age out generally have lived for many years in troubled homes before child welfare intervention.

Characteristics of Young Adults Aging Out of Foster Care

Research on the health and well-being of current and former foster youth during young adulthood is limited. Nevertheless, studies conducted over the past two decades provide a fairly consistent picture, offering somber evidence of the difficulty of transitioning to adulthood for former foster youth:

__________________

4 The terms “emancipation” and “discharge to independent living” are not the same as “legally emancipated minor,” which typically describes an individual under age 18 who has been rendered legally independent of control by parents and courts.

- Former foster youth are less likely to graduate from high school than their peers, and they have low rates of college attendance (Cook et al., 1991; Courtney and Dworsky, 2006; Courtney et al., 2001, 2011; Pecora et al., 2005).

- They have more problems with mental health than the general population (Courtney and Dworsky, 2006; Keller et al., 2010; McMillen et al., 2005; Pecora et al., 2005), often experience poorer physical health than other young adults (Ahrens et al., 2010; Courtney and Dworsky, 2006; Courtney et al., 2001), and have been found by most studies to have high rates of drug and alcohol abuse and dependence (Keller et al., 2010; Pecora et al., 2005).

- Compared with the general population, they have a much higher rate of criminal justice system involvement (Courtney and Dworsky, 2006; Courtney et al., 2001, 2011; Cusick et al., 2012).

- They have difficulties achieving financial independence. Compared with the general population, for example, former foster youth have a higher rate of public assistance dependency (Barth, 1990; Cook et al., 1991; Courtney and Dworsky, 2006; Courtney et al., 2001, 2011; Pecora et al., 2005), are more likely to be unemployed (Cook et al., 1991; Courtney and Dworsky, 2006; Courtney et al., 2011; Goerge et al., 2002), have lower wages (Barth, 1990; Cook et al., 1991; Courtney et al., 2011; Dworsky and Courtney, 2001; Goerge et al., 2002; Pecora et al., 2005), and are much more likely to report various economic hardships (Courtney et al., 2011). They also experience high levels of housing instability and homelessness (Cook et al., 1991; Courtney and Dworsky, 2006; Courtney et al., 2001; Dworsky et al., 2013; Pecora et al., 2005).

- They are less likely than their peers to marry or cohabitate (Courtney et al., 2010) but have higher rates of nonmarital parenting (Cook et al., 1991; Courtney and Dworsky, 2006; Courtney et al., 2011); more children (Courtney and Dworsky, 2006; Courtney et al., 2011); and more nonresident children, including those placed in foster care or for adoption (Courtney et al., 2011).

Programs for Young Adults Aging Out of Foster Care

Current federal policy provides several sources of support for youth transitioning to adulthood from foster care: funding for independent living services, education and training vouchers to support postsecondary education for foster youth up to age 23, health insurance through the Medicaid program up to age 26, and partial reimbursement to states for continuation of foster care up to age 21. Federal funding for services intended to help prepare young people in care for adulthood comes through

the John H. Chafee Foster Care Independence Program (CFCIP), part of Title IV-E of the Social Security Act. Created in 1999 to address perceived limitations of its predecessor, the Independent Living Initiative of 1986, this program is intended to serve individuals who are likely to stay in care until they age out, those who leave foster care for kinship guardianship or adoption after their 16th birthday, and 18- to 21-year-olds who have aged out (SSA, 2014). The program provides states with $140 million annually in funding for independent living services, including outreach programs for eligible individuals, basic living skills training, education and employment assistance, counseling, case management, and transition planning. States can use up to 30 percent for room and board. The law creating the CFCIP also allowed states to extend eligibility for Medicaid to individuals up to age 21 who had been in foster care, but this policy has been superseded by a provision of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) discussed below. The CFCIP was amended in 2002 to allow Congress to appropriate up to $60 million annually for vouchers of up to $5,000 per year for postsecondary education and training for individuals up to age 23. CFCIP-eligible youth are eligible for these vouchers. Approximately $44 million is the estimated appropriation for FY 2014 (GSA, 2014a).

The Department of Health and Human Services developed regulations for assessing state performance in managing independent living programs. These regulations established the National Youth in Transition Database (NYTD) and require that states collect data on (1) each youth receiving independent living services through the state agency that administers the CFCIP, and (2) transition outcomes from program-eligible foster youth cohorts at ages 17, 19, and 21. This data collection focuses on six outcome domains: financial self-sufficiency, experience with homelessness, educational attainment, positive connections with adults, high-risk behavior, and access to health insurance (ACF, 2012). States began collecting NYTD data in late 2010 and report data to the federal government semiannually. The NYTD has the potential to become a nationwide longitudinal database for former foster youth (at least through age 21) who are transitioning to adulthood in the United States. Furthermore, the 1999 law establishing the CFCIP sets aside 1.5 percent of funding for rigorous evaluations of promising independent living programs.5

The Fostering Connections Act of 2008 extends the foster care entitlement, providing states with the option to continue to provide foster care support until age 21 to individuals who are either “(1) completing secondary education or a program leading to an equivalent credential, (2) enrolled in an institution which provides postsecondary or vocational education,

__________________

5 See p. 356 for a description of the first round of program evaluations conducted under this provision of the law, the Multi-Site Evaluation of Foster Youth Programs.

(3) participating in a program or activity designed to promote, or remove barriers to, employment, (4) employed for at least 80 hours per month, or (5) incapable of doing any of these activities . . . due to a medical condition.” Young adults aged 18-21 can “be placed in a supervised setting in which they are living independently, as well as in a foster family home, kinship foster home, or group care facility” (Courtney, 2010, p. 123). States also can continue adoption assistance and/or payments to guardians on behalf of individuals through age 21 if the adoption or guardianship was arranged after the youth turned 16 (Courtney, 2010). In addition, the Fostering Connections Act requires child welfare agencies to help youth and young adults aged 18-21 develop a personalized transition plan during the 90 days immediately before they exit from care between ages 18 and 21. The new law does not alter the CFCIP; states still can use CFCIP funds for a variety of transition services (Courtney, 2010). As of spring 2014, 24 states had federally approved plans for providing foster care past age 18 (Jim Casey Youth Opportunities Initiative, 2014).

Lastly, the ACA requires states to provide, as of January 2014, the full Medicaid benefit available in their state until age 26 to all young adults who were in foster care on their 18th birthday (Emam and Golden, 2014). This provision of the ACA is not affected by the Supreme Court decision allowing states the option of extending Medicaid; in other words, all youth in foster care on their 18th birthday are now eligible for Medicaid in their state of origin up to age 26. States have the option of providing coverage to all foster youth regardless of which state system they have aged out of, but are not required to provide Medicaid benefits to foster youth who have aged out of care in other states.

Evidence for the Effectiveness of Programs for Young Adults Aging Out of Foster Care

Research provides some support for the policy option under the Fostering Connections Act allowing foster youth to remain in care past age 18. Studies relying on differences among states in the age at which youth are discharged from care have shown that extending care to age 21 is associated with increased educational attainment (Courtney et al., 2007), higher earnings (Hook and Courtney, 2011), delayed pregnancy (Dworsky and Courtney, 2010), reduced crime among females (Lee et al., 2012), and delayed homelessness (Dworsky et al., 2013). Studies also indicate that when youth age out of foster care, their health insurance may be discontinued, which contributes to decreases in utilization of physical and mental health services (Courtney et al., 2005b; Kushel et al., 2007; McMillen and Raghavan, 2009).

However, little evidence exists regarding the effectiveness of specific pro-

grams and practices targeting young adults aging out of care. Montgomery and colleagues (2006) reviewed evaluation research on the effectiveness of independent living services and found no experimental evaluations; they concluded that the validity of findings from prior nonexperimental evaluations was severely tempered by methodological limitations. More recently, the Administration for Children and Families (ACF) sponsored the Multi-Site Evaluation of Foster Youth Programs, which is part of the evaluation research on independent living programs funded by the CFCIP.6 This study involved experimental evaluations of classroom-based life skills training, tutoring, employment support, and intensive case management programs for foster youth. Of the four programs evaluated, only the intensive case management program was found to have positive impacts, most notably on youths’ enrollment and persistence in college. However, these impacts appeared to be mediated by the program’s effect on the probability of youth remaining in care past age 18, implying that the program may have positive impacts only in jurisdictions that have opted to extend care.

Fortunately, the federally supported program of rigorous evaluation of interventions targeting youth aging out of foster care is ongoing. In addition, implementation of the NYTD provisions requiring tracking of transition outcomes by states for foster youth aged 17-21 may help identify strategies for improving foster youths’ transitions to adulthood. The NYTD potentially provides data with which to analyze how variation among states in policies and service provision influences transition outcomes.

YOUNG ADULTS IN THE JUSTICE SYSTEM

Involvement in the criminal justice system is a clear marker of marginalization for young people in the United States. As noted in earlier chapters of this report, criminal convictions and incarceration negatively affect young adults’ employment, educational attainment, and civic engagement. Moreover, the harm associated with incarceration is borne disproportionately by racial and ethnic minorities, groups likely to experience other forms of social exclusion (NRC, 2014). Unfortunately, high rates of incarceration are common in the United States. A recent National Research Council (NRC) report concludes that “the growth in incarceration rates in the United States over the past 40 years is historically unprecedented and internationally unique” (NRC, 2014, p. 2). That report further concludes that while penal policy over the past four decades may have contributed to a decrease in crime, the magnitude of that decrease is highly uncertain and unlikely to

__________________

6 For more information about the Multi-Site Evaluation of Foster Youth Programs, see http://www.acf.hhs.gov/programs/opre/research/project/multi-site-evaluation-of-foster-youth-programs-chafee-independent-living (accessed October 22, 2014).

have been large, whereas the increase in incarceration is likely to have had a wide range of unwanted social costs. The report recommends that public policy be revised to reduce incarceration, particularly mandatory and long prison sentences, to improve the experience of incarceration and to reduce harm to the families and communities of those who are incarcerated. The recently issued recommendations of an NRC committee studying juvenile justice reform sound a similar note, calling for a shift away from harsh and costly containment and isolation of young people. Instead, that committee recommends that all levels of government contribute to the creation of developmentally appropriate strategies for holding young people accountable for their transgressions while reintegrating them into their families and communities (NRC, 2013).

Characteristics of Young Adults in the Justice System

Millions of young people encounter the criminal justice system each year. Fully 2.7 million young adults aged 18-24 were arrested in 2012 (29 percent of the total number of individuals arrested), along with 1.4 million aged 25-29 (15 percent of the total number arrested) (FBI, 2012). Approximately 410,900 young adults aged 18-24 and 368,800 aged 25-29 were in state or federal prisons or local jails in 2010 (Child Trends, 2012). In addition, 8,875 young adults aged 18-20 were in residential placements operated by the juvenile justice system in 2011 (Sickmund et al., 2013).

Gender, race, and ethnicity are strongly associated with incarceration (NRC, 2014). As noted earlier, young adult males are much more likely than females to be incarcerated; in 2010, among young people aged 18-19, males were almost 16 times more likely than females to be in jail or prison (1.5 percent versus 0.1 percent), and among young adults aged 20-24, the rate of incarceration was nearly 10 times higher for males (2.8 percent) than for females (0.3 percent) (Child Trends, 2012). Black and Hispanic young adults are more likely than their white counterparts to be incarcerated, and this is particularly true for young men. For example, among young men aged 18-19, 3.8 percent of non-Hispanic blacks, 1.5 of Hispanics, and 0.8 percent of non-Hispanic whites were in jail or prison in 2010. Among young men aged 20-24, 8 percent of non-Hispanic blacks, 3.3 percent of Hispanics, and 1.3 percent of whites were incarcerated in 2010. The net result of the association among gender, race, and incarceration is that young black males are particularly likely to be marginalized by incarceration.

Also as noted earlier, many incarcerated young adults are parents, which has implications for both the young adults and their children. In 2007, for example, an estimated 44.1 percent of adults aged 24 or younger in state prisons (43.5 percent of men, 55.4 percent of women) and 45.8 percent of that age group in federal prisons (45.7 percent of men, 47.5 percent

of women) were parents (Glaze and Maruschak, 2008). Research on the impact of parental incarceration on parents and their children has not focused on incarcerated young adults. Nevertheless, research on the broader population has found that parental incarceration is associated with instability in male-female unions, family economic hardship, reductions in fathers’ involvement in their children’s lives, and increased child behavior problems (NRC, 2014).

Young adults involved with the justice system exhibit other characteristics that put them at risk of social marginalization, including mental health problems and drug use, dependence, and abuse. Research has consistently reported high rates (ranging from 20 to 64 percent) of later criminal offense for youth who received public mental health services (Pullmann, 2010). Moreover, studies of state and federal corrections facilities in 2004 and local jails in 2002 found that an estimated 62.6 percent of individuals in state prisons, 57.8 percent of those in federal prisons, and 70.3 percent of those in county jails had a mental health problem (James and Glaze, 2006). In those studies, mental health problems included a recent clinical diagnosis or treatment by a mental health professional and/or recent self-reported symptoms of depression, mania, or psychotic disorders based on the criteria in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV). Young adults were more likely than any other prisoner age group to report a mental health problem (James and Glaze, 2006).

Young adults also are more likely than older adults to report use of illegal drugs immediately prior to incarceration. In 2004, 66.2 percent of prisoners in state and federal prisons reported using illegal drugs in the month prior to the offense that led to their incarceration (Mumola and Karberg, 2006). Similarly, approximately 53 percent of state and 45 percent of federal prisoners reported meeting DSM-IV criteria for drug dependence or abuse during the 12 months prior to their admission to prison. While these data were not reported for specific age groups, given the higher rate of drug use by young adults relative to other age groups (see Chapters 2 and 6), it is likely that their rates of drug dependence and abuse are comparable to if not higher than those of the overall prison population.

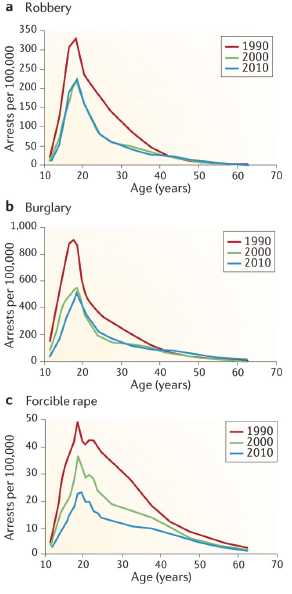

Of course, one of the most important characteristics of young adults involved with the justice system is that, left on their own, most would soon desist from criminal behavior. Social and behavioral scientists have long acknowledged the “age-crime curve,” which illustrates that various forms of antisocial behavior peak in late adolescence and decline rapidly in early adulthood (Farrington, 1986; Hirschi and Gottfredson, 1983; Loeber et al., 2012; Moffitt, 1993; Steinberg, 2013). Figure 8-1 provides some examples of the age-crime curve using Federal Bureau of Investigation arrest data (Steinberg, 2013). It shows a consistent relationship between age and crime; the shape of the curve is similar across time periods and different

types of offence, including robbery, burglary, and forcible rape. Theories explaining this phenomenon have evolved over the past three decades, and recent research suggests that the age at which involvement in crime peaks is influenced by a variety of individual characteristics and conditions, varying to some extent across offenses (Loeber et al., 2012). Nevertheless, those adolescents who begin committing crimes when they are older generally desist from crime as they become adults, and social scientists attribute this pattern primarily to normative developmental processes regarding middle-adolescence peaks in deviancy and sensation seeking, as well as cognitive maturation. Thus, lengthy mandatory sentences and other long-lasting or permanent forms of punishment for criminal behavior by young people (e.g., ineligibility for public welfare benefits and for financial aid for postsecondary education) run counter to current understanding of the relationship between age and crime (NRC, 2013).

Jurisdictional Issues for Young Adults

Young adults who are age 18 and over when charged with a criminal law violation are under the authority of the adult criminal justice system in all states. However, young adults can in some states remain under the jurisdiction of the juvenile courts past the age of 18, and young people can in some places enter the adult criminal justice system as minors. In most states, for example, juvenile courts can retain authority over youth for dispositional purposes in delinquency matters until age 20, and in 4 states this authority extends through age 24 (OJJDP, 2013a). In addition, in certain states, juvenile courts have original authority over cases such as those involving status offenses, abuse, neglect, and dependency matters for those over 18, often through age 20 (OJJDP, 2012). While 39 states limit the original jurisdiction of juvenile courts in criminal matters to youth under age 18, in some states the original jurisdiction of the juvenile court is restricted to youth under age 16. In other words, in such states prosecutions for criminal offenses routinely occur in adult criminal courts rather than juvenile courts for defendants as young as 16. In addition, all states have laws that allow or require criminal prosecution in adult courts for some offenders who are younger than the juvenile side of the jurisdictional age line (Adams and Addie, 2014). Although the precise number of such transfers of juvenile offenders to adult courts is unknown, the practice has become more common in recent years (Griffin et al., 2011).

Recognition of the unique developmental needs of young adults has led some states to create policies and programs specifically for this age group. For example, some states have laws that treat individuals aged 18-21 within a special category that has various names, including “youthful offenders” and “young adult offenders.” For a review of these laws, see Velázquez

(2013). In addition, some states, such as Pennsylvania, have created special corrections facilities for young adults (Loeber et al., 2013).

The U.S. Department of Justice sponsored a Study Group on the Transitions between Juvenile Delinquency and Adult Crime, which focused on ages approximately 15-29 (Loeber et al., 2013). The authors conclude that “young adult offenders aged 18-24 are more similar to juveniles than to adults with respect to their offending, maturation, and life circumstances” (p. 20).

Programs for Young Adults Involved in the Justice System

The federal role in the criminal justice system is limited. For example, federal prisons housed only 216,900 (9.7 percent) of the 2,228,400 inmates in state or federal prisons or in local jails in 2012 (Glaze and Herberman, 2013). Moreover, few federal programs specifically target young adults who are involved in the justice system. The majority of federal programs for justice-involved young adults serve them either alongside adolescents in the juvenile justice system or alongside the general adult population in the criminal justice system. In both of the latter cases, there are virtually no data on what proportion of the population served are young adults or on program effectiveness and outcomes specifically for this age group. We describe here selected federal programs that, among other things, are explicitly intended to assist young adults involved with the justice system.

Several programs of the U.S. Department of Justice’s Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention (OJJDP) include a focus on key outcomes for young adults, such as employment; education; housing stability; safety; health, including avoidance of risk behaviors; connections to responsible adults; and effective parenting. These programs are more directly relevant to young adults than programs that target at-risk minors to prevent them from becoming involved in the juvenile justice system. OJJDP provides formula grants to support “efforts related to delinquency prevention and reduction, juvenile justice system improvement, research, evaluation, statistical analysis, and training and technical assistance in all 50 States, the District of Columbia, and the 5 U.S. territories” (OJJDP, 2009a, p. 1). States provide subgrants to local government and private agencies and to American Indian tribes. Program areas include mental health, substance abuse, education, and job training. In federal FY 2012, $33 million was obligated, with a 10 percent matching requirement; in federal FY 2013 and 2014, an estimated $41 million and $70 million was obligated, respectively (GSA, 2014c).

OJJDP also provides funding to states through the Juvenile Accountability Block Grant (JABG) program. The aim of this program is to “hold youth accountable for delinquent behavior through the imposition of

graduated sanctions that are consistent with the severity of the offense” and “strengthen the juvenile justice system’s capacity to process cases efficiently and work with community partners to keep youth from reoffending” (OJJDP, 2009b, p. 1). Target areas that are relevant to key outcomes for young adults include a variety of school-related behaviors, job skills and employment status, family relationships and functioning, and substance use (OJJDP, 2013c). In federal FY 2013, $23 million was obligated, with a 10 percent matching requirement; in federal FY 2014 and 2015, an estimated $30 million per year was obligated (GSA, 2014b).

Several components of the Title V Community Prevention Grants Program are directly relevant to key outcomes for young adults, including community-based programs that provide job training and mental health and substance abuse services (OJJDP, 2013d). In addition to the block and formula grants programs, various OJJDP discretionary programs are relevant, including the Second Chance Act Grant Program, mentoring programs, and programs for tribal youth.

Program data and performance measures collected on these programs through OJJDP’s reporting system provide information on how many of the grantees serve young adults aged 18 and older (OJJDP, 2014). For the formula grants described above, data from the most recent reporting period indicate that 139 of 280 grantees served young adults over age 18 (OJJDP, 2013b). Data from the most recent reporting period of the JABG program indicate that 215 of 242 grantees served young adults over age 18 (OJJDP, 2013c). However, these data do not break out information on the number or characteristics of young adults served, nor do they break out performance measures by age group.

In addition to OJJDP-funded programs, several other federally funded programs include justice system-involved young adults among their target populations. The Reintegration of Ex-Offenders program, administered by the U.S. Department of Labor’s Employment Training Administration (ETA), includes programs aimed at both youthful offenders and adults (DOL, 2014). The youthful offenders program targets youth and young adults aged 14-24 who have been involved in the juvenile justice system but not the adult criminal justice system, and in some cases limits participation to those aged 18-24. The adult program serves individuals aged 18 and older who have been convicted and imprisoned within the adult criminal justice system. This program is intended to reduce recidivism by supporting employment, vocational training and educational interventions, and mentoring. Housing and substance abuse treatment are not provided using ETA funds. Through a competitive grants process, ETA offers funding to community- and faith-based organizations that provide services to ex-offenders. The ultimate goal is to use effectiveness evaluations of these demonstration and pilot programs to inform the development of state and

local programs that can improve ex-offenders’ workforce outcomes. In federal FY 2013, $79 million was obligated; estimated amounts for federal FY 2014 and 2015 are $74 million and $78 million, respectively (GSA, 2014d). An experimental impact evaluation of this program is being conducted, focused exclusively on those over 18 who have been convicted and imprisoned as adults, but results have yet to be reported (Leshnick et al., 2012).

Job Corps, administered by the U.S. Department of Labor, offers high school education, vocational training, and health care to low-income, at-risk youth and young adults aged 16-24. In the 2011 program year, more than 43,000 young adults aged 18-24 participated, representing 79.2 percent of a total 55,000 participants (Job Corps, 2012). Job Corps does not explicitly target justice-involved young adults; in fact, a condition of eligibility is that the person not have face-to-face court or institutional supervision or court-imposed fines during the time he or she participates in the program (Job Corps, 2013). However, according to a review by Welsh and colleagues (2013) examining job training and education programs for at-risk youth, Job Corps has demonstrated modest benefits for participants in the areas of reduced criminal activity, improved educational attainment, and increased earnings (Schochet et al., 2008; Welsh et al., 2013).

YouthBuild is another program administered by the U.S. Department of Labor that includes young adults with justice system involvement as a target population (YouthBuild USA, 2014d). Participants work full-time for 6-24 months toward their General Educational Development (GED) credential or high school diploma in YouthBuild programs while learning job skills by building affordable housing. YouthBuild’s program philosophy emphasizes leadership development, community service, and creation of a community of adults and youth committed to each other’s success. The program is intended to place young people in college, jobs, or both at program exit. A participant must be aged 16-24 at entrance, and at least 75 percent of participants in a YouthBuild site must have dropped out of high school and belong to one of the program’s target populations, which include

- youthful offenders,

- adult offenders,

- current and former foster youth,

- youth with disabilities,

- migrant farm worker youth,

- children with an incarcerated parent, and

- low-income youth.

While offenders are a target population for YouthBuild, only about one-third of program participants are court involved (YouthBuild USA, 2014a). In addition, the waiver of eligibility criteria for up to 25 percent of pro-

gram participants and the imposition of additional optional program eligibility criteria, such as minimum reading level and drug testing, by some YouthBuild sites likely results in the exclusion of many difficult-to-serve young adults.

Currently there are 264 YouthBuild programs across 46 states, the District of Columbia, and the Virgin Islands (YouthBuild USA, 2014d). These programs engage approximately 10,000 participants per year (YouthBuild USA, 2014d), predominantly men (71 percent), and a large proportion (53 percent) are African American (YouthBuild USA, 2014a). In federal FY 2013, $72 million was obligated; estimated amounts for FY 2014 and 2015 are $75 million and $74 million, respectively (GSA, 2014f). YouthBuild program administrative data indicate that in 2010, 78 percent of participants completed the program, 63 percent of these obtained their GED credential or high school diploma, and three-fifths were placed in college or in jobs with an average wage of $9.20/hour (YouthBuild USA, 2014a). The Department of Labor commissioned an evaluation of YouthBuild in 2010; results are expected in 2017 (Mathematica Policy Research, 2014; MDRC, 2014).

In addition to its core program, YouthBuild is implementing an initiative aimed at young people aged 16-24 who have been in the juvenile justice system. The SMART (Start Making a Real Transformation) initiative enhances YouthBuild’s core program model with additional program elements such as mentoring, flexible programming, alternative career tracks, and community-based crime and violence prevention activities (YouthBuild USA, 2014c). The U.S. Department of Labor has provided $8.5 million toward this demonstration program, which currently serves more than 550 youth across nine sites.

The National Forum on Youth Violence Prevention brings together communities and federal agencies—including the U.S. Departments of Justice, Education, Health and Human Services, Housing and Urban Development (HUD), and Labor and the Office of National Drug Control Policy—to address youth and gang violence in the United States. As of March 2014, 10 communities were involved in the forum: Boston, Camden, Chicago, Detroit, Memphis, Minneapolis, New Orleans, Philadelphia, Salinas, and San Jose (FindYouthInfo, 2014). The foundational strategy document for the forum states that “strategies should include prevention efforts spanning from early childhood into young adulthood, such as youth development, family support, school and community mentoring, and school-based and out-of-school recreational activities” (National Forum on Youth Violence Prevention, 2011, p. 7). However, the extent to which any or all of the participating communities have focused a significant part of their efforts on young adults is unclear.

Lastly, various federal programs serve adults in the criminal justice

system and upon reentry into the community. These programs include the Reintegration of Ex-Offenders program, described above, and U.S. Department of Justice programs such as the Second Chance Act Prisoner Reentry Initiative and the Serious and Violent Offender Reentry Initiative. The Second Chance Act Prisoner Reentry Initiative provides funding for “state, tribal, and local reentry courts; family-based substance abuse treatment; evaluate and improve education at prisons, jails, and juvenile facilities; technology careers training demonstration grants; offender reentry substance abuse and criminal justice collaboration; adult and juvenile demonstration; [and] mentoring grants to nonprofit organizations” (GSA, 2014e, p. 1). In federal FY 2013, $63 million was obligated; in federal FY 2014 and 2015, an estimated $68 and $115 million was obligated, respectively (GSA, 2014e).

This overview reveals that justice-involved young adults are eligible for many programs—juvenile and adult—that provide services relevant to the key outcomes for this age group, such as avoidance of further justice system involvement, employment skills, and education. With the exception of a small number of programs that target young adults, however, little is known about the size of the young adult population served by these programs and how much of the program funding is spent on this population. Even less is known about whether these programs improve outcomes for young adults. Moreover, some of these programs apply eligibility criteria that exclude many young adults in the greatest need of assistance.

Evidence for the Effectiveness of Programs for Young Adults in the Justice System

With the exception of Job Corps, evidence for the impact of the major federally supported programs described above on the health and well-being of young adults is sparse. However, since the programs have yet to be subjected to rigorous evaluation, and available program data seldom distinguish young adults from other populations served, this lack of evidence should not lead one to conclude that these government investments have had no impact on young adults. Moreover, a variety of interventions other than those currently funded by the federal government may improve the health and well-being of young adults. A recent review of the effectiveness of prevention and intervention programs was conducted for the National Institute of Justice Study Group on the Transitions between Juvenile Delinquency and Adult Crime to assess the impact of these programs on individuals in the transitional period between adolescence and young adulthood (Welsh et al., 2013). The primary focus of the review was on serious offending in young adulthood, but it included other outcomes as well, focusing on

- “Programs implemented during the later juvenile years (ages 15-17) that have measured the impact on offending in early adulthood (ages 18-29)

- Programs implemented in early adulthood that have measured the impact on offending up to age 29

- Programs implemented in early childhood that have measured the impact on offending in early adulthood.” (Welsh et al., 2013, pp. 4-5)

The review assessed the impacts of prevention and intervention programs focused on family, peers and community, school, the labor market, and the individual. The authors conclude that “there is a paucity of high-quality evaluations of programs that have measured the impact on offending in early adulthood” (Welsh et al., 2013, p. 33). They identified certain promising early prevention programs in preschools and schools that appear to impact offending and other important outcomes into the young adult years. They also found some promising family-based interventions for adjudicated delinquents (but operating in an environment outside of the juvenile justice system) that reduce offending in young adulthood. With the exception of the Job Corps study described above, Welsh and colleagues did not identify programs implemented exclusively in young adulthood that impact offending up to age 29. However, they did find that “the available evidence about intervention modalities used with both juvenile and adult offenders indicates that their effects are substantially similar. This generality across the major age divide in juvenile and criminal justice implies that such programs should be effective with young adult offenders as well” (Welsh et al., 2013, p. 34). The four broad intervention modalities they identified that had positive effects were (1) cognitive-behavioral therapy; (2) educational, vocational, and employment programs; (3) drug treatment; and (4) treatment for sex offenders. They also found that for both adolescents and adults, “sanctions and incarceration appear to have essentially negligible or slightly undesirable effects” (Welsh et al., 2013, p. 29).

Many young adults spend time with no stable residence, living on the streets or “couch surfing” from one unstable living arrangement to another. Unfortunately, no reasonably current and reliable data are available regarding the size and characteristics of the homeless young adult population nationally. Moreover, studies of local populations vary in their definition of homelessness and often include adolescents and older adults, making it

difficult to draw conclusions about the size and needs of the population of homeless young adults.

Characteristics of Homeless Young Adults

Estimates of the size of the population of homeless young adults range widely; for example, estimates of the number of young adults aged 18-24 who experience a homelessness episode each year vary from about 750,000 to 2 million (Ammerman et al., 2004). However, most estimates are based on extrapolations from studies of local populations and the number of individuals who come into contact with providers of homeless services. The most recent national estimate based on data from service providers comes from the 2013 Annual Homeless Assessment Report to Congress from the HUD (2013). This estimate is based on a point-in-time count of the number of sheltered and unsheltered homeless people derived from reports from Continuums of Care, local planning bodies responsible for coordinating homelessness services within HUD-defined geographic areas. According to HUD, there were 610,042 homeless individuals on a given night in January 2013, 65 percent of whom were living in emergency shelters or transitional housing and 35 percent of whom were living in unsheltered locations. Ten percent of these individuals (61,541) were aged 18-24. About two-thirds of these young adults (40,727) were unaccompanied youth (i.e., they were not a part of a family during their homeless spell), half of whom were unsheltered at the time (HUD, 2013). Using HUD data on young adults reported in adult emergency shelter or transitional housing programs (i.e., excluding unsheltered youth), the National Alliance to End Homelessness estimated that approximately 150,000 youth aged 18-24 utilized these services at some point during 2011 (National Alliance to End Homelessness, 2012).

Although many studies of homeless youth include both minors and young adults and rely on convenience samples or samples drawn from local populations of service recipients, the available research supports the following general conclusions regarding the vulnerability experienced by homeless young people (see, e.g., Burt et al., 1999; Hagan and McCarthy, 2005; Toro et al., 2007; Whitbeck, 2009):

- They are likely to have grown up in a low-income family.

- Their family relationships are likely to be strained or nonexistent.

- They are likely to have experienced childhood maltreatment and trauma.

- Many experience physical and sexual victimization into adulthood.

- They experience high rates of mental and behavioral health problems.

- They are likely to engage in risky sexual behavior.

- Many become parents at an early age.

- They are likely to be unemployed and work outside of the legal economy.

- They lag behind their peers in educational attainment.

Not surprisingly, these young people also are likely to have come into contact with other systems that serve vulnerable young adults (e.g., the foster care and criminal justice systems).

Programs for Homeless Young Adults

The Runaway and Homeless Youth Act (RHYA) is the primary source of federal support for services to homeless young adults, although some of the programs funded by the act focus primarily on homeless minors (Fernandes-Alcantara, 2013). The Runaway and Homeless Youth Program,7 administered by the Family and Youth Services Bureau within the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ ACF, supports street outreach, emergency shelters, and transitional living and maternity group home programs for young people at risk of or experiencing homelessness. These programs are operated by public and private social service agencies and federally recognized tribes. The RHYA programs received approximately $110 million in FY 2013 (National Alliance to End Homelessness, 2013). Each of these programs is described below.

Basic Center Program (BCP)

The BCP provides youth and their families with short-term shelter and services. In FY 2013, a total of $45.1 million was allocated to 303 BCP-funded centers—about $150,000 per center (ACF, 2014b). The centers provide emergency shelter, food, clothing, counseling, and referrals to health care providers for youth up to age 18. The majority of centers provide up to 20 youth with 21 days of shelter. BCP-funded centers focus on reuniting young people with their families or locating appropriate alternative placements when reunification is not possible. Some centers offer street-based services, home-based services, and substance abuse education and prevention services for homeless young adults older than 18 (Fernandes-Alcantara, 2013). BCP centers were designed to offer these services outside of the law

__________________

7 For more information about the Runaway and Homeless Youth Program, see the ACF program website: http://www.acf.hhs.gov/programs/fysb/programs/runaway-homeless-youth/ (accessed October 22, 2014).

enforcement, juvenile justice, child welfare, and mental health systems, although centers conduct outreach to these systems to identify eligible youth.

In 2011, BCP centers reported serving 38,758 youth with preventive or shelter services (ACF, 2013a). Slightly more than half of these youth were female. African Americans and Native Americans were overrepresented among the youth served relative to their proportions of the general population. According to data from the Runaway and Homeless Youth Management Information System, or RHYMIS, lesbian, gay, bisexual, and questioning youth make up about 6-7 percent of BCP-served youth, although program providers believe these figures may understate the prevalence of sexual minority youth served by their programs (ACF, 2013a).

Transitional Living Program (TLP)

The TLP supports programs that provide long-term (up to 21 months) residential services to homeless youth aged 16-22. Youth who are pregnant or parenting are eligible for TLP services (see the description of the Maternity Group Home [MGH] Program below). In FY 2013, 206 programs received a total of $37.2 million—about $180,000 per program (ACF, 2014c). TLP grantees may shelter up to 20 youth in a variety of settings, including host family homes, maternity homes, apartments supervised and owned by a social service agency, or apartments rented with agency assistance (ACF, 2013a). TLP providers are required to provide young people with the following services: safe and stable living accommodations, basic life-skills building, interpersonal skills building, education and employment services, substance abuse counseling, mental health care, and physical health care. In 2011, the TLP served a total of 4,104 young people (ACF, 2013a). More than half of the youth served are 18 or 19 when they enter a shelter. About 60 percent of program participants are female, while African Americans, Native Americans, and Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders are overrepresented relative to their proportions of the general population. Based on RHYMIS data, lesbian, gay, bisexual, and questioning youth make up about one-tenth of the young people served by TLP providers. About 30 percent of youth served, both male and female, were pregnant or parenting when they entered the program.

The MGH Program, funded by ACF through the TLP, provides services for up to 21 months to homeless young people aged 16-22 who are pregnant or parenting and their dependent children (ACF, 2013a). In addition to standard TLP services, the MGH Program offers services designed to help young people improve their parenting skills, knowledge of child development, family budgeting, and health and nutrition, as well as access affordable child care and early childhood education services.

Street Outreach Program (SOP)

The SOP targets runaway and homeless young people living on the streets or in areas that increase their risk of being subjected to sexual abuse or exploitation. The program is intended to help youth transition to safe and appropriate living arrangements (ACF, 2013b). Services include street-based education and outreach, crisis intervention, access to emergency shelter, needs assessments, treatment and counseling, information and referrals to other services, prevention and education activities, and follow-up. In FY 2013, 107 SOPs received a total of $14.8 million—about $138,000 per program (ACF, 2013b). Outreach workers do not collect detailed information about the demographic characteristics of youth served, and the program cannot provide unduplicated counts of the number of youth served, but the 155 grantees funded through the program in 2011 reported making 693,270 contacts with youth that year (ACF, 2013a).

Other Programs Providing Assistance to Homeless Young Adults

A variety of other federal programs that do not specifically target young people undoubtedly provide assistance to homeless young adults. Federally funded programs for which at least some homeless young adults are eligible include Continuum of Care programs; the Emergency Shelter Grants program; the Housing Opportunities for Persons with AIDS program; Veterans Affairs Supportive Housing; the Community Development Block Grants program; the Housing Choice Voucher program (Section 8, for which youth aging out of foster care are a targeted population under the Family Unification Program); the Public Housing program; and Section 811 Supportive Housing for Persons with Disabilities. With the exception of the annual point-in-time survey conducted by Continuum of Care providers described above, however, data are not readily available on the numbers of young adults served by these programs. States and localities also fund a variety of programs that provide assistance to young adults, but the size of the populations served and the amount of funding for such services are unknown.

In summary, while no reliable data exist regarding the size of the homeless young adult population, available data on service receipt indicate that at least several hundred thousand homeless young people come to the attention of federally funded service providers each year. Moreover, service providers report turning away many homeless youth in need of assistance, and studies of homeless youth populations indicate that many of these youth do not access services, suggesting that the number of homeless young adults is much higher than counts of service recipients would indicate (Fernandes-Alcantara, 2013; Toro et al., 2007). Homeless young adults also exhibit many indicators of marginality beyond their lack of residential

stability. Lastly, while the exact amount spent on federally and state-funded services for homeless young adults is unknown, it is certainly in the tens of millions of dollars per year.

Evidence for the Effectiveness of Programs for Homeless Young Adults

Little is known about the effectiveness of federally funded programs for homeless young adults. While ACF is in the process of establishing performance standards for RHYA programs and improving its data collection system to monitor key program outcomes, there are as yet no reliable data on postprogram participation outcomes for young people served by these programs. Nor are data available on outcomes for young adults served by other federal programs.

Moreover, research on the effectiveness of interventions targeting homeless youth,8 while identifying promising programs, has failed to establish the effectiveness of programs in improving outcomes for young adults. Reviews of the evaluation literature conclude that rigorous evaluation of services for homeless youth is sorely needed (see, e.g., Altena et al., 2010; Slesnick et al., 2009; Toro et al., 2007). Knowledge of the effectiveness of these services is limited by the poor quality and small number of intervention studies and the heterogeneity of interventions, participants, research methods, and outcomes assessed.

As noted in Chapter 3, given that about half of all first births are to women aged 26 or younger, it is not at all unusual for young adults to be parents (Martin et al., 2013). Nevertheless, while many young parents thrive personally and are able to parent their children effectively, having children early is a marker of vulnerability for many young adults, as well as their children.

Characteristics of Young Parents

On average, young parents are more likely than older parents to be raising children under circumstances that pose risks to themselves and to the future of their children, as described below. About two-thirds of parents under age 25 are single parents, making them more than twice as likely as older parents to be leading a single-parent household (Vespa et al., 2013).

__________________

8 Almost all evaluation research on homeless youth has focused exclusively or primarily on homeless minors rather than homeless young adults.

And of course, by virtue of their place in the life course, they are more likely than older parents to be parenting young children.

Being a parent and having young children both are associated with an increased likelihood of living in poverty during early adulthood, particularly for single parents. For example, families headed by young adults aged 18-24, especially single-mother families,9 have higher rates of poverty than families headed by individuals 25 and older (Redd et al., 2011). The poverty rate for families with single mothers aged 18-24 as the head of household was 67 percent in 2010, compared with 27.9 percent among married-couple families of the same age (Redd et al., 2011). Moreover, single mothers aged 18-24 were much more likely to live in poverty than single mothers aged 25-34 (48.7 percent), 35-44 (33.8 percent), or 45-54 (30.1 percent). Having young children also is associated with living in poverty (Redd et al., 2011). Higher rates of poverty have been found in families with children under age 6 compared with all families with children under age 18. This is especially true for families headed by single mothers; in 2010, 54 percent of families headed by single mothers with children under age 6 lived in poverty, compared with 40.7 percent of families headed by single mothers with children under age 18 (Redd et al., 2011).

Programs for Young Parents

While young parents are served by a wide variety of government programs, we focus here on three federally supported programs: TANF, the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), and the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC). These programs, while not targeting young adults, nevertheless serve a large number of low-income young parents. Moreover, young parents make up a significant proportion of the service population of each.

TANF

TANF is intended to help needy families achieve economic self-sufficiency. The TANF block grant provides states funding with which to design and operate programs that accomplish one of the following four purposes:

- provide assistance to needy families so children can be cared for in their own homes;

- reduce the reliance of needy parents on public aid by promoting job preparation, work, and marriage;

__________________

9 Single mothers accounted for 95 percent of all single parents under age 25 in 2012 (Vespa et al., 2013).

- prevent and reduce nonmarital pregnancies; and

- encourage the formation and maintenance of two-parent families (ACF, 2014a).

The TANF block grant was funded at $16.5 billion in FY 2013 (Falk, 2013). To receive federal TANF funds, states must contribute at least $10.4 billion of their own funds under a maintenance-of-effort (MOE) requirement.

TANF funds may be used broadly for the purposes described above. In FY 2012, $31.4 billion of both federal TANF and state MOE funds was either expended for TANF program purposes or transferred to other block grant programs (e.g., the Child Care and Development Block Grant or Social Services Block Grant) (Falk, 2013). In contrast with its predecessor Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC) program, most TANF funds are not used for cash assistance to low-income parents and their children (Falk, 2013). Funding for basic assistance, which most closely reflects cash assistance, was $9 billion in FY 2012, or 28.6 percent of total TANF and MOE dollars. TANF is a major source of funding for child care for low-income parents. In FY 2012, 16.0 percent of TANF funds was spent on child care or transferred to the child care block grant (Falk, 2013). TANF also is a major source of funding for state child welfare systems, although the TANF accounting system is poor at capturing expenditures that are associated with child welfare services. States use TANF funds for foster care, kinship foster care, adoption assistance, and services to families with children who have been maltreated or are at risk of maltreatment. Most TANF funding for child welfare programs is subsumed in the “other” spending category, which accounted for 31 percent of TANF and state MOE spending in FY 2012 (Falk, 2013). A survey of state child welfare agencies found that TANF funds accounted for 20 percent of total federal, state, and local expenditures on child welfare programs in FY 2004 (Scarcella et al., 2006). The remainder of TANF and MOE funds expended in FY 2012 went to “other work supports” (9.6 percent), administration (7.2 percent), and “work expenditures” (6.9 percent) (Falk, 2013). Because TANF is a fixed block grant, its value has declined considerably over time; the inflation-adjusted value of the TANF block grant declined by 30.1 percent between 1997, its first full year of operation, and 2012 (Falk, 2013).

Individuals living in a household that receives TANF support are either considered “work-eligible” or exempted from the work requirements of the law. The latter group includes primarily adult nonrecipients who are non-parental caregivers of TANF-eligible children (e.g., a grandparent, aunt, or uncle). TANF provides assistance to some of the most disadvantaged American families (Falk, 2012). In FY 2009, for example, two-thirds of families with work-eligible individuals that received TANF cash assistance reported

no other source of cash income. Even including their TANF benefits, more than three-quarters of these families had incomes below 50 percent of the federal poverty level (Falk, 2012).

Although data are unavailable on the ages of all TANF recipients who are not work eligible, states provide the federal government with some demographic information on work-eligible program participants (Falk, 2012). A large proportion of adult TANF program participants are young adults; in FY 2009 nearly one-third (32.2 percent) of work-eligible individuals receiving TANF were under age 25, and more than half (54 percent) were under 30 (Falk, 2012). In FY 2009, 85 percent of work-eligible individuals were women, 73 percent of whom had never been married. Racial and ethnic minorities (African Americans and Hispanics) made up a majority of TANF work-eligible individuals. More than two-fifths (43 percent) of work-eligible TANF participants lacked a high school diploma or equivalent.

SNAP

SNAP provides food-purchasing assistance for low-income people. Formerly known as the Food Stamp program, it is an entitlement program administered by the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), although benefits are distributed by state government agencies. SNAP is the nation’s largest nutrition assistance program, having served an average of 47.6 million people per month in 2013 and providing a total of $76 billion in benefits over the course of the fiscal year (USDA, 2014b). The average monthly benefit per individual in FY 2013 was $133.07. Actual food stamps were phased out starting in the late 1990s, and today states provide SNAP benefits through the Electronic Benefit Transfer (EBT) debit card system (USDA, 2013a). Households may use the benefits, which are deposited directly into their accounts, to pay for food at eligible food retailers.

A household’s size, income, and expenses help determine the amount of assistance the household receives (USDA, 2014a). In addition, able-bodied working adults aged 18-50 without dependents only receive SNAP benefits for 3 months in a 36-month period if they do not work or take part in a workfare or employment and training program. States currently are allowed to waive this requirement for unemployed working-age adults without children in specific areas with high unemployment rates. In general, able-bodied individuals aged 16-60 must register for work, accept reasonable employment, and take part in employment and training programs they are referred to by local SNAP offices or risk disqualification from the program.

Despite the work requirements that limit SNAP assistance for adults without children, young adults make up a significant proportion of SNAP beneficiaries. In 2011, an average of 4.3 million low-income young adults aged 18-24 received SNAP benefits each month (Lower-Basch, 2013). Ap-

proximately 2.7 million of these young adults were living in households with minor children.

WIC

Like SNAP, WIC is administered by USDA, although unlike SNAP it is not an entitlement program. WIC provides benefits to eligible pregnant, breastfeeding, and postpartum women; infants; and children up to age 5 (USDA, 2013b). To be eligible, individuals must be at nutritional risk and have a family income of less than 185 percent of the federal poverty level. Participants in other benefit programs, including SNAP, Medicaid, and TANF, automatically meet the WIC income eligibility requirement. WIC is intended to improve fetal development and reduce the incidence of low birth weight, short gestation, and anemia during the prenatal period for pregnant women and their unborn children. It also is intended to provide nutritious foods during critical times of growth and development for infants and young children to improve their health and prevent health problems. WIC benefits include supplemental foods, nutrition education and counseling (including breastfeeding promotion and support), and referrals to health and social service providers. Eligible applicants can purchase specific types of food (for example, milk, juice, and cereal) from participating retail vendors at no charge using vouchers, checks, or EBT cards. WIC expenditures in FY 2012 totaled $6.8 billion (Johnson et al., 2013); 9.7 million participants were enrolled in WIC in April 2012 (Johnson et al., 2013). Available program data do not provide estimates of the young adult population participating in WIC, but 85.9 percent of all women participants were aged 18-34.

Evidence for the Effectiveness of Programs for Young Parents

Estimating the effects of TANF on young parents is complicated by several factors. First, nearly all studies of the employment and antipoverty effects of TANF are quite dated. This means that outcomes generally were measured when the employment rate of young adults was quite different from what it has been in recent years and before the program’s federal work requirements were significantly revised. Second, much of the research on TANF considers how replacing the individual entitlement to cash assistance in place prior to 1996 with today’s work-based welfare program has influenced such outcomes as parental employment, earnings and poverty, material hardship, and child well-being. While those studies help inform debates over the wisdom of the fundamental change in the social safety net occasioned by welfare reform, they provide little or no information about whether the current TANF program helps the families it serves gain

employment or otherwise improve their well-being. Nor do data collected by state TANF programs provide this information, if for no other reason than that TANF administrative data provide no information on postprogram outcomes. Third, the federal government gives states such discretion in operating TANF that it is more a flexible funding stream than a distinct program whose outcomes can be evaluated. Lastly, even the few studies that have sought to evaluate approaches to TANF provision do not provide information about young adults as a distinct population.

For these and other reasons, research has shed little light on whether the TANF program improves the employment and economic well-being of young parents, but its impact is likely minimal. While there have been many studies of the labor supply disincentive effects of the old cash assistance program (Danziger et al., 1981; Moffitt, 1992), TANF differs from a classic means-tested cash assistance program because of the potential work incentives provided by its work requirements and time limits. Unfortunately, there have been no studies of the labor supply effects of the current TANF program in terms of its impact on the hours current recipients would work in the program’s absence (Ben-Shalom et al., 2011). And while analyses of the effects of TANF on poverty have not distinguished young adults from the broader population of parents, the estimated effects for low-income parents in general are small (Ben-Shalom et al., 2011).

The reduction in the size of the TANF caseload also has implications for the program’s likely impact on young adults. Because state TANF caseloads have declined considerably since AFDC was replaced by TANF, fewer low-income families have been in a position to benefit from TANF as time has passed. For example, approximately 68 percent of families in the United States with children living in poverty received cash assistance through AFDC in 1996, but by 2010 only 27 percent of such families were receiving cash assistance through TANF (Trisi and Pavetti, 2012). Moreover, as the TANF caseload has declined, it appears to have increasingly comprised parents with significant obstacles to obtaining and maintaining employment, including low educational attainment, health problems, learning disabilities, histories of domestic violence, mental health disorders, substance abuse, and involvement with child protection authorities (Blank, 2007; Courtney et al., 2005a; Dworsky et al., 2007). Whether TANF is optimally designed for such needy populations is questionable, but many young adult parents exhibit these obstacles to employment.

An important measure of the effectiveness of SNAP is its ability to reduce food insecurity, defined by USDA as a household-level economic and

social condition of limited or uncertain access to adequate food.10 While the magnitude of the effects varies, studies of SNAP generally have concluded that program participation reduces food insecurity among the adults and children served (Mabli et al., 2013; Mykerezi and Mills, 2010; Ratcliffe et al., 2011). For example, one study found that SNAP benefits reduce the incidence of food insecurity by approximately 30 percent (Ratcliffe et al., 2011).

WIC is intended primarily to help low-income children, not their parents, although young parents arguably benefit from improvements in the well-being of their children. Although the range of estimated benefits is large, research on the effects of WIC participation generally has concluded that the program improves low-income children’s health at birth (Bitler and Currie, 2005; Chatterji et al., 2002; Figlio et al., 2009; Joyce et al., 2008; Lee and Mackey-Bilaver, 2007; Rossin-Slater, 2013).

In Chapter 3, we review research on the benefits of two-generation programs that use strategies addressing the developmental needs of both young parents and their children. These programs target marginalized young parents, who need the increased social capital and connections to the workforce promoted by many of these programs (Chase-Lansdale and Brooks-Gunn, 2014; King et al., 2009).