Scoping, Problem Formulation, and Identifying Alternatives

Early in the chemical alternatives assessment process, the assessor needs to determine the level of stakeholder engagement and delineate the goals, principles, and decision rules that will provide the context for and guide the assessment. This step is called scoping. The assessor will also need to determine the assessment boundaries and methods—problem formulation—and identify the alternatives that will be considered.

These early steps are often overlooked in existing alternatives assessment frameworks. However, they are important and can improve efficiency by focusing limited resources on a reasonable range of viable alternatives, increase transparency of the assessment, and support informed substitution processes and minimize regrettable substitutions. The goal of the chemical alternatives assessment is to identify safer alternatives that can be used to replace chemicals of concern in products or processes, so it is important that the steps outlined in this chapter support efficient, scientifically informed alternatives assessment processes and do not lead to over-analysis, or so-called “paralysis by analysis.”

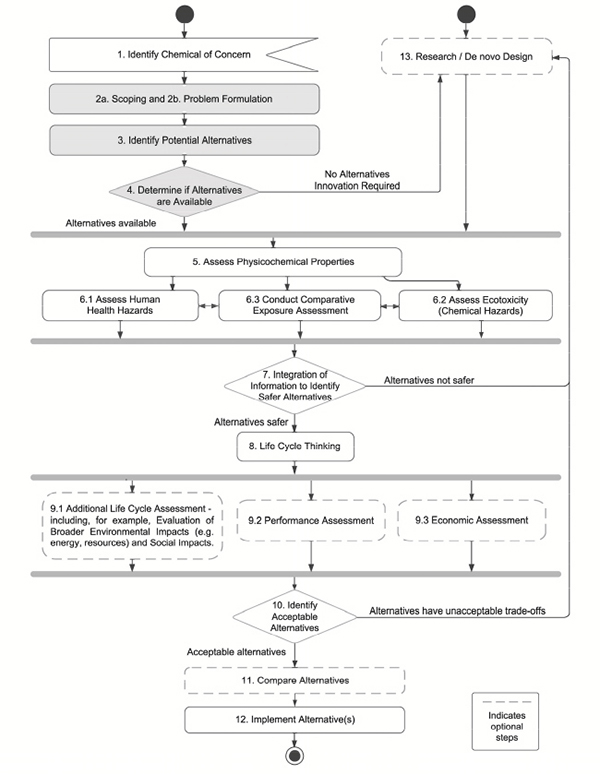

This chapter describes the elements of scoping and problem formulation (see Box 4-1, Step 2 in the committee’s framework) and discusses the process for identifying alternatives (see Box 4-1, Step 3 in the committee’s framework).

SCOPING, PROBLEM FORMULATION, AND IDENTIFYING ALTERNATIVES IN OTHER FRAMEWORKS

Most of the frameworks examined by the committee have some reference to scoping, problem formulation, and alternatives identification, although the steps typically are not well developed. Only a few provide explicit guidance on scoping that notes stakeholder engagement or decision rules to guide the assessment. For example, the Lowell Center framework includes an initial element called “Alternatives Assessment Foundation,” in which goals, principles, and decision rules are established; examples are provided (Rossi et al. 2006). The IC2 Guide includes a “Stakeholder” module in which decisions are made concerning which stakeholders should be involved in the assessment. The IC2 Guide describes specific decision rules and principles that guide its framework (IC2 2013).

The majority of frameworks contain some type of problem formulation element, but most do not include an extensive characterization of the chemical of concern. For example, the Biz-NGO framework includes a “Characterize End Use and Function” step (Rossi et al. 2012). The TURI framework includes a “functional use prioritization” step (TURI 2006a). CA SCP specifies that regulated entities identify life

BOX 4-1

ELEMENTS OF STEPS 2 AND 3 IN THE

COMMITTEE’S FRAMEWORK

Step 2a: Scoping at a Glance

- Identify the relevant stakeholders and determine their role in the assessment process.

- Describe the goals, principles, and decision rules that will be used in the assessment.

Step 2b: Problem Formulation at a Glance

- Gather information on the chemical of concern.

- Determine the assessment methods that will be used.

Step 3: Identifying Potential Alternatives at a Glance

- Identify alternatives from expert and stakeholder input and literature review.

- Gather preliminary data on potential alternatives.

- Conduct initial screen, if indicated.

cycle segments and exposures that are most likely to be of concern for alternatives in bounding their alternatives assessments (CA DTSC 2013a). The IC2 framework contains a “Framework” module in which the decision framework and assessment modules to be included in the alternatives assessment are chosen, and an initial screening of attributes of concern for alternatives is conducted (IC2 2013). All the frameworks include some type of alternatives identification step, although only some, such as the TURI framework, contain an initial screening element.

SCOPING IN THE COMMITTEE’S FRAMEWORK

In the committee’s framework, scoping is the initial process in an alternatives assessment, in which the level of stakeholder engagement is determined, and the goals, principles, and decision rules are described (see Box 4-2 for the committee’s definitions of these terms). Scoping decisions are generally driven by particular policy mandates or organizational or corporate values. That is, how stakeholders will be engaged in the assessment and what goals, principles, and decision rules will guide the process are determined at the corporate level. Thus, the individual assessor or team will not make those decisions per se but will describe for each assessment the level of stakeholder engagement and the goals, principles, and decision rules that will be applied in the assessment process. The committee notes that for broad participation in the alternatives assessment process, transparency will be necessary. The following sections detail the elements of the scoping step.

Stakeholder Engagement in the Chemical Alternatives Assessment Process

Alternatives assessments are interdisciplinary by nature because they draw on organizational expertise in chemistry, engineering, toxicology, exposure assessment, cost analysis, and other disciplines. Expert advisors who are able to provide critical information and advice to inform the assessment process might also be needed. The multidisciplinary teams, however, might not fully understand the options, hazards, trade-offs, and barriers to adoption of an alternative; thus, it is important to involve stakeholders in the alternatives assessment process. The term stakeholder is broadly defined by the committee and includes internal and external members of an organization. Stakeholders are not necessarily expert advisors because they tend to be identified by the fact that they might be positively or negatively affected by the particular decision and are not usually an integral part of the decision-making team.

BOX 4-2

DEFINITIONS OF GOAL, PRINCIPLES, AND DECISION RULES

Goal: Desired outcome of an agency, organization, or corporation. For example, a goal could be “to support the informed transition to functional, cost-effective, and safer alternatives.”

Principle: A value or tenet of an agency, organization, or corporation. For example, a principle could be “to protect children’s health.”

Decision rule: A specific action that helps to implement or enact the principles. For example, a decision rule could be “do not accept reproductive and development hazards as viable alternatives.”

Stakeholder engagement in the committee’s alternatives assessment process spans the length of the assessment, from scoping, problem formulation, and identification of alternatives through to the ultimate adoption of an alternative. The committee’s use of stakeholders is consistent with best practices in assessment processes that advocate stakeholder input from problem definition through ultimate decision-making (NRC 1996, 2009). Stakeholder engagement is also included in several other existing alternatives assessment frameworks (Edwards et al. 2011; OECD 2013a). As noted, the extent of stakeholder engagement is generally defined by legal mandates or organizational values and probably will depend on who is conducting the assessment.

Roles for Stakeholders in the Alternatives Assessment Process

The committee identified several critical reasons for stakeholder engagement in the alternatives assessment process. First, stakeholder engagement can help identify alternatives for a chemical of concern that might not be identified by an organization’s chemists or process engineers. For example, one group of stakeholders includes workers, who use a chemical in a product or process and might have ideas about alternatives that are not readily apparent to engineers or designers.

These stakeholders might be able to provide critical information on performance requirements that might lead to favoring one alternative over another. Suppliers, another group of stakeholders, might have information on alternatives that a manufacturer might not consider.

Second, stakeholders might have access to data on chemical hazards that are not readily accessible. These data could include important information on chemical use and potential exposures that should be considered in the alternatives assessment process. Such stakeholder engagement helps avoid potential unintended consequences of substitution processes. Third, if the assessment methods and assumptions are made known to relevant stakeholders, they might be able to provide useful input and help identify or solve possible problems or major data gaps.

Fourth, stakeholder engagement is critical to the adoption of alternatives. An alternative will not be viable if the end user rejects it. Adoption of alternatives might require changes in process conditions or work habits. Although such changes do not provide a rationale to avoid substitution, it is important to engage affected stakeholders so that they understand specific changes and can develop training and work practices needed to support the effective adoption of an alternative.

Fifth, some laws require stakeholder engagement in the alternatives assessment process. CA SCP specifically requires stakeholder consultation in reviewing the lists of chemicals of concern, the product or chemical combinations for which alternatives assessments will be required, and the alternatives assessment results (CA DTSC 2013a). Likewise, the Massachusetts Toxics Use Reduction Act mandates that workers be involved in the alternatives assessment process (MGL Chap. 21I). Specific third- party certification processes, such as Green Seal, have requirements for stakeholder engagement in defining criteria for safer products and in their specific review (Green Seal 2009).

Level of Stakeholder Engagement in the Alternatives Assessments Process

The extent of stakeholder engagement depends on the context of the alternatives assessment process, which includes legal mandates, organizational values, and potential implications of a substitution. At this stage, it is particularly important to identify those stakeholders who might be able to provide important input in the identification, evaluation, or adoption of alternatives and to determine the degree to which they will participate in the process. Depending on the alternatives assessment, those stakeholders might include workers, trade organizations, regulators, community members, suppliers, and customers.

The following three levels of stakeholder engagement were described in the IC2 framework and should be considered when using the committee’s alternatives assessment framework.

- A corporate or organizational exercise that identifies potential stakeholders, their concerns, and how their concerns might be addressed in the alternatives assessment.

- A process that identifies potential external stakeholders and actively seeks their input in a formal and structured process.

- A process in which stakeholders are invited to participate in all aspects of the alternatives assessment, from scoping to adoption of an alternative. Stakeholders could also serve on the assessment team and review the final assessment product.

The different levels of stakeholder engagement have increasing resource and process requirements. As such, it is important to identify stakeholder engagement needs at the earliest point in the assessment to gain the most benefit from stakeholder involvement. It is also important to avoid overextending such engagement, causing the assessment process to become too cumbersome or paralyzed by stakeholder input. Additional guidance concerning stakeholder engagement can be found in the EPA’s DfE (EPA 2014c) and the IC2 (IC2 2013). The result of this step should be a clearly documented plan for stakeholder engagement that outlines processes, roles, and responsibilities.

Goals, Principles, and Decision Rules

Assessment goals are most often set by the organization or entity responsible for performing the assessment. Thus, the goals and principles that guide an alternatives assessment process often reflect whether the assessment ultimately will be used to support regulatory, corporate, or other decision-making processes. As in most scientific assessment processes, a number of implicit or explicit values underlie the decisions. Previous NRC reports note that given the underlying science policy and context-dependent nature of risk-assessment processes,

transparency in values and assumptions is critical (NRC 1996, 2009). To that end, the committee recommends that an important scoping step is documentation of goals, principles, and decision rules guiding the assessment. Once they are established, the appropriate methods and tools for completing the assessment become clearer.

Goals and Principles

The overall goal of the assessment should be explicitly stated. As noted in Chapters 1 and 3, an overarching goal of alternatives assessments conducted using the committee’s framework is to identify and support the informed transition to functional, cost-effective, and safer alternatives. This broad goal is consistent with other frameworks and many organizational goals. For example, SC Johnson produced the Green List evaluation process with the goal of moving toward the safest chemical ingredients for particular applications (SC Johnson 2014). Additionally, California’s SCP program has a goal “to reduce toxic chemicals in consumer products, create new business opportunities in the emerging safer consumer products economy, and reduce the burden on consumers and businesses struggling to identify what’s in the products they buy for their families and customers” (CA DTSC 2014). The SCP regulations “aim to create safer substitutes for hazardous ingredients in consumer products sold in California” (CA DTSC 2014). Government agencies, such as EPA’s Office of Pollution Prevention (EPA 2012d), also have overarching programmatic goals that promote pollution prevention and the use of safer chemicals.

The principles that represent desirable outcomes and help guide the actions of an organization should also be explicitly stated. As noted in Chapter 2, various frameworks have identified principles for alternatives assessment. For example, the EPA’s DfE program has adopted a set of principles to ensure the value and utility of its analyses, such as alternatives must be commercially available, technologically feasible, and have an improved health and environmental profile (EPA 2012e). Chapter 3 describes the committee’s thinking underlying the development of its alternatives assessment framework. The principles and thinking described in Chapters 1 and 3 can provide the basis for each organization to develop the goals and principles underlying its assessments.

Decision Rules

In addition to goals and principles, organizations need to develop decision rules to guide the assessment process. They are typically derived from the goals and principles of the assessment, implemented during the evaluation steps, and can help facilitate the assessment when resources are limited. They can be helpful in reducing the number of alternatives to be evaluated in detail; for example, by eliminating from consideration specific alternatives on the basis of early performance, toxicity, or regulatory concern indicators.

Examples of some decision rules might include (Rossi et al. 2006):

- Avoid specific types of chemicals, such as persistent, bioaccumulative, and toxic (PBT) chemicals or carcinogens, regardless of exposure potential.

- Avoid chemicals that might affect critical populations, such as children.

- Evaluate only alternatives made in manufacturing facilities that have strong human rights records.

As described in detail in Chapter 9, there also can be decision rules on, for example, how missing data might be addressed, how to consider trade-offs between domains (for example, between human health and ecotoxicity) or how to weight end points within a domain. In some cases, decision rules might be dictated by policies, such as regulations in the CA SCP, which require examination of hazards and potential exposures throughout the chemical or product life cycle.

Collectively, the goals, principles, and decision rules help guide the assessment process used for choosing the best alternatives and can help resolve trade-offs that might result from integrating results across different attribute domains, such as toxicity, material and energy use, and cost. For example, the California Safer Consumer Products regulations require that alternatives be better than the original chemical in the areas of concern (CA DTSC 2013a). The Biz-NGO framework specifically focuses on hazard reduction as a key goal for alternatives (Rossi et al. 2012), and the GreenScreen® tool lays out specific criteria for lower hazard chemicals (Clean Production Action 2014). Some alternatives assessment frameworks, such as UCLA MCDA, include specific steps aimed at understanding stakeholder values that can guide choices in resolving complex trade-offs (Malloy et al. 2011). As emphasized earlier, the goals, principles, and decision rules should be clearly documented and

communicated to assessors completing later steps of the framework.

PROBLEM FORMULATION IN THE COMMITTEE’S FRAMEWORK

The goal of problem formulation is to establish a baseline and boundaries for the assessment that will help focus resources and outline a plan for the assessment. This step could be termed the “planning” phase of the assessment because it involves determining what health effects, exposure pathways, life cycle segments, and performance attributes will need to be considered. At the conclusion of this exercise, the assessor might be able to anticipate where trade-offs will occur in the substitution process.

Gathering Information on the Chemical of Concern

As noted in Chapter 3, to assess alternatives successfully, it is important to characterize the chemical of concern, including its chemical identity, functions, applications, performance requirements, toxicity, and potential exposure pathways. Understanding those characteristics and properties will help focus the assessment on functions or applications of greatest concern and provide a baseline for comparing and identifying potentially viable alternatives. The following discussion outlines the information that is needed for problem formulation.

Chemical Identity

Defining the chemical of concern clearly is the first part of information-gathering process. For example, is it an individual chemical, a chemical mixture, an entire chemical class, or an unintended by-product, or breakdown product of a specific chemical? How the chemical of concern is defined (for example, all polybrominated diphenyl ethers) can be driven by public policy or by the principles and decision rules of an organization. Identification of the chemical entity (or process) will serve to define chemical functions and limit the number of alternatives that need to be considered.

Function and Application

Before determining the chemical requirements and identifying potential alternatives, the assessor must first understand the functions, applications, and processes associated with the chemical of concern. The committee makes a distinction between function and application. A function is the service that the chemical broadly provides, such as solvent, adhesive, or coating. An application is the more specific use of the chemical, such as a solvent in a cleaning formulation, an adhesive in a specific electronic device, or a coating in food containers. These distinctions help identify appropriate alternatives (see Box 4-3). The committee’s framework focuses primarily on assessment of chemical substitutions, although substitutions could involve process or product redesign.

To evaluate function, the assessor should consider the following questions:

- What is the particular function of the chemical, and how is it used in a particular application? At a company level, this characterization will be narrow and might be focused on one function and application. At a government or purchaser (such as a hospital) level, there might be several functions and applications to consider for a chemical of concern.

- Is the chemical’s function necessary for the product or process? Certain functions might not be necessary to achieve product performance, such as antimicrobials in hand soaps or flame retardants in certain types of products. If that function is not required, it might be possible to eliminate the chemical of concern altogether.

- Is the chemical of interest intentionally added, or is it an unintended by-product in the formulation? If the chemical is an unintended by-product or contaminant, it serves no particular function, and the focus of the assessment might involve identifying ways to reduce or remove the contaminant from the formulation or identifying alternative chemicals that would not create specific by-products or contaminants. In that case, the assessment would focus on the function of the particular chemical resulting in by-product generation.

There are several ways to evaluate chemical function and application for the purposes of alternatives assessments, and there are numerous government and nongovernment options. Most government approaches consist of broad characterizations, such as surfactant or solvent. However, those characterizations might not provide enough detail for manufacturers to determine whether a particular alternative will work in their process or product. Manufacturers will want to

BOX 4-3

WHY FOCUS ON FUNCTION?

Alternatives assessments should consider the particular functions or “services” that a chemical provides in products and processes. This approach enables assessors to explore how and why a chemical is used rather than simply trying to find a chemical alternative to serve as a replacement. This approach can reduce the unintended consequences that might be associated with a “drop-in” substitute to replace a chemical of concern.

A focus on function provides an opportunity for government agencies and companies to screen chemical, material, and product or process redesign options in a comparative manner: by focusing on best-in-class options for a specific function and application. For example, a focus on the function of a solvent as a metal degreaser led the Toxics Use Reduction Institute to explore a range of options to meet that function, such as aqueous solvents, ultrasonic cleaning, and alternative metal-cutting methods, which removed the need for degreasing altogether. Likewise, alternatives to parabens as a preservative in a cosmetic product might include considering other chemical preservatives or entirely different ways of dispensing the soap (such as pumps) to avoid microbial contamination.

Focusing on function can provide opportunities for innovation in safer chemicals and materials. An understanding of a chemical’s function can result in green chemistry attention on the molecular structures that give a chemical its particular physicochemical properties. In this way, chemicals that can serve the same function while minimizing potential toxicity can be considered. A broad focus can lead to materials and product or process design innovation. The connection between alternatives assessment and materials innovation is discussed in greater detail in Chapter 13.

define functions or applications narrowly, so that they can be analyzed more thoroughly; such analysis will lead to more actionable conclusions. However, the downside of such specificity, especially for government-facilitated alternatives assessments, is the need for multiple assessments for each particular application of a chemical rather than simply one assessment for the primary function.

TURI identified a number of functions and critical applications for five chemicals of concern for which alternatives assessments had been completed (TURI 2006b). TURI prioritized the functions and applications of the five chemicals (such as phthalates in flexible PVC sheeting) on the basis of key uses in Massachusetts and opportunities for substitution. Thus, characterizing function and application, particularly for government alternatives assessments, provides an opportunity to focus the alternatives assessment on issues of greatest priority, such as exposure potential to sensitive populations, availability of potential alternatives, market or regulatory interest, or value to an entity, for a particular chemical of concern.

The outcome of this exercise is an evaluation of the function of the chemical of concern in a particular application or for placement on a list specifying functions of the highest priority for assessment. Not only does this step provide important input for identifying alternatives but can also provide important information for understanding potential hazards and exposures for the chemical of concern and potential alternatives.

Performance Requirements

Alternatives must meet the performance requirements of the original chemical formulation, material, product, or process, including compliance with applicable legal and customer requirements. Accordingly, once the functions and key applications of a chemical of concern have been identified, the performance requirements need to be identified as well. The purpose of defining performance requirements at the problem-formulation stage is to help identify viable alternatives and collect preliminary information for the performance evaluation and testing that might occur later in the alternatives assessment process (Step 9.2 in the committee’s framework). Some legislation, such as the European Union’s REACH, requires users to outline the full performance requirements at the problem formulation phase (ECHA 2011).

Although a more detailed performance assessment (including performance testing) generally occurs in later phases of an alternatives assessment, the assessor might wish to conduct an initial screen of alternatives against performance requirements to screen out those alternatives that clearly will not meet performance requirements. In fact, substantive performance testing for some established alternatives might already have been completed. Such screening can help focus the hazard and exposure assessments on the most technically viable alternatives. In some cases, it might be advantageous to complete even more detailed performance evaluations early in the alternatives assessment process; for example, when alternatives must meet certain specifications, or the list of potential alternatives is large. However, an alternative that

does not meet certain requirements at this point should not necessarily be eliminated from consideration, although it might be assigned a lower initial priority. Correctly bounding the performance requirements increases the probability that the assessment process will find the most cost-effective, efficacious, and innovative solutions. The committee notes that defining and evaluating performance is an iterative process, and as noted, will need to be revisited later in the assessment process (Step 9.2). One approach to defining performance requirements is described in detail in the REACH framework (ECHA 2011) and also referenced by the IC2 framework (IC2 2013).

The committee’s framework includes the following:

- a. Define specific function: Although the function and application were characterized in the problem formulation step, the specific function should be defined in detail at this stage. For example, the general function of a substance might be as a solvent, but the specific function that it performs within a formulation could be to dissolve flux residue left behind from hand-soldering operations. Additional information, such as the type or chemical composition of flux residues, might be needed. The more completely the function can be defined, the easier it will be to set criteria to determine whether a potential alternative can be successful.(

- b. Identify relevant properties: The relevant structures and physicochemical properties that determine the chemical’s functions should be identified, if possible. In some cases, the properties that impart a specific function might not be fully understood.

- c. Define acceptability criteria: It is important to specify the acceptability criteria for potential alternatives at the chemical level, the formulation or material level, the product level, or the process level, as appropriate. Acceptability criteria might include values or ranges of critical properties, such as boiling point, vapor pressure, or water solubility, that are determined on the basis of process or use conditions. It should be noted that a company might require a high level of specificity in its acceptability criteria, whereas a consortium, consultancy, or regulator might be satisfied with general criteria as long as they are sufficient to ensure basic functionality.

- d. Determine appropriate methods for testing alternatives against criteria: In some cases, it might be possible to use established standards or test methods to evaluate criteria. For example, the efficacy of general purpose cleaners can be evaluated using the test method ASTM G122–96(2002) Standard Test Method for Evaluating the Effectiveness of Cleaning Agents, and a pass-fail criteria can include the stipulation that the product must remove at least 80% of the particulate or greasy soils (EPA 2012d). If standard methods are not available, qualitative methods might be required or specialized test methods might need to be developed to establish tolerance ranges.

- e. Identify regulatory, customer, specification, and certification requirements: Certain types of products and materials might require specific performance levels to meet regulatory, specification (such as military specification), or other certification requirements. Those requirements and any accompanying test methods should be defined explicitly.

- f. Identify process or use conditions or constraints: In addition to acceptability criteria, the process or use conditions required or expected during the performance of the function should be identified. They might include a specific temperature range; pH; purity, or presence of other chemicals; and other specific process constraints, such as drying time or process cycle time. The process and use information identified in this step might be useful in identifying potential exposure pathways.

The outcome of this exercise is a documented set of performance requirements for the particular function and application that the alternative will need to satisfy, as well as a plan for performance evaluation at the alternatives identification or performance assessment steps. The committee notes that it is important to not define the criteria too narrowly or too broadly. Defining criteria too broadly can lead to the selection of alternatives that fail to perform the central function. On the other hand, defining criteria too narrowly could lead to the rejection of alternatives that have markedly improved human health or environmental performance. These alternatives could be developed as suitable replacements, perhaps through other adjustments in the product, formulation, or process.

Human Health and Environmental Effects, Exposure Pathways, and Life Cycle Segments

Once the chemical function, application, and performance requirements have been identified, it is important to identify the human health and environmental effects associated with the chemical of concern. This information provides a baseline for comparison of the chemical with potential alternatives evaluated later in the committee’s framework.

This step is also important for alternatives assessment planning in that it can help identify effects, exposure pathways, life cycle segments, and impacts of greatest concern for the chemical of concern. Once these features have been identified, they can be used as points of comparison between the chemical of concern and potential alternatives, which might exhibit similar hazard properties, exposures, or life cycle effects. These comparisons are appropriate because the use profile for the alternative and the chemical of concern are expected to be similar in the final product. Thus, this activity can help focus (or bound) the evaluations in Steps 5, 6, 8, 9.1, and 9.

The process for completing this step for the chemical of concern includes the following:

- Characterization of physicochemical properties and hazards: At the problem-formulation stage, it is important to develop a matrix of physicochemical properties and relevant human and ecological hazards for the chemical of concern, particularly those that have been identified as problematic. Additional details concerning relevant physicochemical properties and ecological and human health hazards to consider are discussed in detail in Chapters 5, 7, and 8 of this report.

-

Identification of use scenarios and exposure pathways: It is important to know how the chemical of concern is used in a process or product to be able to identify its exposure pathways. Mapping the exposure pathways is designed to help in the interpretation of hazard data, not to curtail looking at hazards. That said, however, there may be some narrowing of focus in the hazard assessment. Expected patterns (acute vs. chronic) and routes (oral, dermal, inhalation) of exposure likely to be important can be identified given reasonably foreseeable exposure scenarios. A full exposure assessment is not needed at this stage; what is needed is enough understanding of exposure to determine exposure pathways of greatest interest for later assessment.

Discussions with a variety of stakeholders, such as raw material suppliers, workers, communities, customers, and regulatory agencies, may assist in the identification of a variety of positive or negative exposure-related consequences, which may have been identified initially during the scoping exercise. For example, upstream consequences include those associated with the production, use, and storage of precursor chemicals and raw materials, and the production and use of energy and other materials. Other consequences include near-field exposures of workers along the production pathway, as well as the product’s users; site-level or community-level exposures associated with upstream and product manufacturing facilities or at the point-of-use; and far-field exposures with potential impacts on distant human and ecological receptors from either upstream or downstream exposures.

-

Identification of life cycle segments that require additional consideration (life cycle segments of concern): The purpose of this exercise is to identify and anticipate portions of the chemical of concern’s life cycle that might need to be evaluated in Steps 8 and 9.1 and to make sure that the alternatives (identified in Step 7 of the committee’s framework) also undergo this evaluation. The tasks that need to be completed are identifying concerns inherent to the chemical, such as toxicity of the building blocks and breakdown products, and those that are external, context-based concerns, such as energy and resource use and social impacts, over the chemical’s life cycle. With that information in hand, it becomes possible to look at the alternatives in light of where important differences or trade-offs may be. A full life cycle evaluation is not needed at this point, because such assessments are costly. The goal is simply to identify areas of concern and to determine the focus of the assessment that will take place during Steps 8 and 9.

Some chemicals or chemical processes can result in the creation of by-products (or breakdown products) or involve other chemicals of concern during production of the final chemical. At this stage, such concerns associated with the “synthetic history” (intermediates, by-products, and breakdown products) of the chemical of concern should be

- identified because they will help in planning Steps 5, 6, and 8 in the committee’s framework.

-

Specific chemicals or chemical processes also might have resource and energy impacts that are important to consider in the assessment, or there might be easily identifiable changes in potential life cycle impacts that need to be considered (for example, a change from a petroleum-based chemical to a biologically based chemical). Identifying life cycle segments of concern can help guide Life Cycle Thinking in Step 8.

The outcome of this step is a documented characterization of the chemical of interest that identifies its hazard profile, exposure pathways of concern, and anticipated life cycle segments of concern that should be evaluated in Step 8. This information might need to be augmented in later stages of the assessment as additional knowledge is gathered on potential alternatives. However, the goal at this stage is to have the information necessary to create a clear, focused plan for the assessment process.

Determining Assessment Methods

After human health and environmental hazards, exposure pathways, and life cycle segments of concern have been identified, decisions need to be made regarding the methods that will be used in the alternatives assessment. The methods should be clearly documented and include information on which assessment steps will be conducted, what hazard end points will be evaluated, what tools will be used to compare alternatives, and what approach will be used to address uncertainty. Some of the choices, particularly decision rules, are outlined in the Scoping exercise. Elements of the assessment, such as end points to examine and assessment steps to include, might need to be modified on the basis of knowledge gained throughout the assessment process. While the committee’s framework is designed to be iterative and flexible, including flexibility in how each step is implemented depending on available resources, it does emphasize that documenting methodological choices must take place. This process is critical for minimizing concerns about whether the assessment has predetermined outcomes.

- Assessment Steps: Determining which framework steps—human health, ecological, exposure, performance, life cycle, economic or other evaluations—to include in the assessment should be identified at the outset. Making this decision can depend on the organization completing the alternatives assessment; the values driving the assessment (defined earlier); the use of the assessment (regulatory, non-regulatory, product development); issues identified in the assessment of hazards, exposure pathways, and life cycle segments of the chemical of concern; or knowledge about the nature of the particular product and chemical use. At a minimum, Steps 1-8 should be included in each assessment.

- Tools to Evaluate and Compare Alternatives: As noted in Chapters 5-8, there are a number of tools and approaches used in different frameworks to assess human and ecological hazards and intrinsic properties of alternatives. Although the tools are generally similar, there are some differences. In particular, specific end points to be evaluated and criteria for determining the degree of hazard might differ between frameworks, although many use decision criteria from the Globally Harmonized System of Classification and Labelling. The tools used in each framework might also differ in the data streams used to inform the assessment. Chapters 5, 7, and 8 provide guidance on end points and data streams to consider in the assessment process. Before conducting the assessment, the following decisions should be made:

-

- which data streams and end points to evaluate,

- how to compare alternatives (for example, qualitative vs. quantitative approach), and

- how to present results (for example, numerical score vs. tabular or graphical format).

Making these decisions a priori will help to reduce bias in the assessment process. The committee notes that at a minimum, the physicochemical properties discussed in Chapter 5, comparative exposure discussed in Chapter 6, ecotoxicity discussed in Chapter 7, and the human health hazard end points discussed in Chapter 8 should be considered. Furthermore, how alternatives are compared will depend on the scope of the assessment. Comparing alternatives can be simple when the data are clear and there are not many options (IC2 2013). If many criteria are being considered or the data are not clear, the comparison becomes more complex.

- Tradeoff strategies to determine which chemicals are “safer”: The definition of safer alternatives (Step 7) depends on the framework or tool used to evaluate and compare alternatives. Some, like the EPA’s DfE framework, provide criteria for high, medium, and low scores for each end point, but there is no weighting of end points (EPA 2014c). In this instance, an assessor must determine what makes an alternative safer. The GreenScreen® tool, however, has benchmarks from one to four that are based on hazard and physicochemical properties, and they provide explicit weighting of which alternatives are safer (Atlee 2012). Other frameworks or tools implicitly weight certain hazards, such as human health, higher than other hazards, such as ecological.

-

Strategies for addressing uncertainty and data quality: There will almost always be data gaps and uncertainty in an alternatives assessment. Chapters 5-8 provide some guidance on how uncertainties might be reduced through the alternatives assessment process. A variety of methods could be used to address data gaps. For example, certain data gaps can be addressed using models or alternative data streams. How such gaps are addressed can depend on the tools being used to evaluate and compare hazards and other attributes and decision rules established in the scoping process. In any case, it is important to document how data gaps will be addressed early in the assessment.

Data quality is also addressed in several frameworks and tools. For example, the DfE framework has “data hierarchies” that indicate the types of data that are preferred in the hazard assessment process (EPA 2011a). The organization completing the assessment should outline early in the process what data will be used or preferred in the assessment (quantitative, qualitative, only lists, and government databases) and how data will be obtained.

The output of this exercise is a clearly documented, methodological plan for the alternatives assessment that will guide later steps. As noted, on the basis of the data being obtained, changes in methods might be warranted, but such changes should always be clearly documented.

IDENTIFYING ALTERNATIVES IN THE COMMITTEE’S FRAMEWORK

The committee’s alternatives assessment framework includes a step (Step 3) that involves identifying alternatives. The purpose of this step is to identify a range of potential alternatives that meets a particular function in a product or process. In some cases, for example, if the number of alternatives is large and needs to be reduced, an initial screening based on goals, principles, decision rules, and performance criteria, as described in Step 2, can be completed. The goal here is to identify a range of viable alternatives and then to assess them through Steps 5 and 6 of the assessment.

Identifying a Range of Alternatives

For the purposes of the present report, the goal of the alternatives assessment is to evaluate safer alternatives for a particular chemical of concern for a particular function. In general, the initial alternatives identification should involve a broad range of stakeholders to ensure breadth and creativity of options. At this point, the alternatives identification should focus on available alternatives and those that might be on the horizon and highlight those that represent more than marginal improvements over the chemical of concern, given the costs associated with product or process reformulation. Options that seem unlikely should not necessarily be eliminated.

The breadth of alternatives to be considered in the assessment process should be made explicit in the scoping step. Often, an organization might want to evaluate only relatively simple chemical substitutes that do not result in substantial product or production process redesign requirements (known as drop-in substitutes). Such substitutions can be made more rapidly, often at a lower initial cost. In other contexts, an organization might want to consider greater chemical changes, including substantial product reformulation or redesign. A broad range of options can increase the complexity of the alternatives assessment because exposure pathways or hazard profiles of alternatives can be substantially different. Alternatives can be identified through a number of strategies, including review of scientific and trade literature and industry publications, interactions with suppliers, and engagement with experts in a company, government agencies, or technological institutes.

Initial Screening of Identified Alternatives

If the number of identified alternatives is large, it might be necessary to screen the list to a more manageable number for further assessment and potential adoption. Screening also can help prevent potentially regrettable substitutions for toxicity or performance reasons. That said, however, it might be useful to retain alternatives that appear to be improvements, particularly if few alternatives are available. What is important at this point is to identify those alternatives that clearly will not meet required functional, legal, or customer requirements. The screening process might also identify where there is a need for green chemistry and materials innovation (see Chapter 13). It is important to note that this initial screening is not a full assessment process, but rather a screen to limit the range of alternatives evaluated in depth in Steps 5 and 6 to a manageable size.

The first consideration in the screening process involves identifying those alternatives that might not be technically viable on the basis of performance. Although alternatives are often eliminated from consideration because of the potential to increase costs, at this point, cost should not be considered a determining factor. There are ways to reduce costs through process changes or purchasing agreements. Furthermore, although the unit cost of a chemical replacement might be higher, the comparison might not consider the range of cost reductions associated with an alternative chemical or material, including those related to durability, permitting, insurance, disposal, and liability. Those questions are more effectively considered in the economic and performance analyses (Steps 9.2 and 9.3) that occur after the comparative chemical hazard assessment.

The second consideration is based on toxicity or exposure concerns. This screening can be done rapidly by using authoritative lists or hazard classifications, as described in Chapter 8, but the listing criteria need to be transparent, understood by the assessor, and consistent with the criteria used to establish evidence of the health end point that the list is addressing. Several alternatives assessment tools include this approach as a screening step. Many countries and key stakeholders, including customers, have lists of chemicals that they choose to limit or ban on the basis of toxicity concerns, such as mutagenicity and reproductive toxicity, or PBT characteristics. Under the European Union’s REACH legislation, the European Chemicals Agency (ECHA) has created a “very high concern” list of chemicals that will be highly regulated, making the import or use of them difficult (ECHA 2014a). Although such regulations have geographical limits, most companies today use global supply chains, and restricting the use of a chemical in one geographic region is also likely to affect other regions. As alternatives are being assessed, knowing what limitations (restrictions or exposure limits) already exist for the use of certain chemicals can help inform the assessment of alternatives.

The final consideration in the screening process involves reviewing goals, principles, and decision rules (identified in the scoping step), including the public commitments that a company has made that would affect products or chemicals they use or sell. For example, a company might have a decision rule to avoid all chemicals that are potential carcinogens or endocrine disruptors; any chemical meeting those criteria should be eliminated at this point.

It is important to recognize that this screening activity only eliminates clearly inferior or unacceptable alternatives on the basis of performance, toxicity, or exposure. It should result in a reasonable narrowing of alternatives to those that appear to be the most viable. Whatever the outcome, it is important to identify clearly the screening criteria. Alternatives eliminated from consideration at this step should be documented as a record of what was considered, in case they need to be reconsidered at later stages of the assessment (for example, in cases where new information regarding toxicity becomes available or where other alternatives are not viable).