Accurate eyewitness identifications1 may aid in the apprehension and prosecution of the perpetrators of crimes. However, inaccurate identifications may lead to the prosecution of innocent persons while the guilty party goes free. It is therefore crucial to develop eyewitness identification procedures that achieve maximum accuracy and reliability.

Eyewitness evidence is not infallible. In 1932, Yale University law professor Edwin M. Borchard documented nearly seventy cases of miscarriage of justice caused by eyewitness errors in his book, Convicting the Innocent.2 Years later, in 1967, the U.S. Supreme Court highlighted the danger of erroneous eyewitness identification in United States v. Wade, stating, “The vagaries of eyewitness identification are well-known; the annals of criminal law are rife with instances of mistaken identification.”3

The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) estimates that U.S. law enforcement made 12,196,959 arrests in 2012. The FBI estimates that 521,196 of these arrests were for violent crimes.4 Accurate data on the number of crimes observed by eyewitnesses are not available. If only a fraction of the violent crimes in the United States involve an eyewitness, the number must

_______________

1Throughout this report, the term identification denotes person recognition. Eyewitness identification refers to recognition by a witness to a crime of a culprit unknown to the witness.

2Edwin M. Borchard, Convicting the Innocent: Sixty-Five Actual Errors of Criminal Justice (New York: Garden City Publishing Company, Inc., 1932).

3United States v. Wade, 388 U.S. 230, 288 (1967).

4Federal Bureau of Investigation, “Crime in the United States 2012: Persons Arrested,” available at: http://www.fbi.gov/about-us/cjis/ucr/crime-in-the-u.s/2012/crime-in-the-u.s.-2012/persons-arrested/persons-arrested.

BOX 1-1

The Ronald Cotton Casea

In 1984, a college student named Jennifer Thompson was raped in her apartment in Burlington, North Carolina. The police asked her to help create a composite sketch of the rapist. The police then received a tip that a local man named Ronald Cotton resembled the composite, and shortly after the crime, Thompson was shown a photo array containing six photos. With some difficulty, she chose two pictures, one of which was of Cotton. Finally, she said, “I think this is the guy,” pointing to Cotton. “You’re sure,” the lead detective asked, and she responded, “Positive.” Thompson asked, “Did I do OK?” The detectives responded, “You did great.” She has described how those encouraging remarks had the effect of making her more confident in her identification.

The police then showed Thompson a live lineup. Cotton was the only person repeated from the prior photo array. This would make Cotton more familiar and might suggest that he was the prime suspect. Nevertheless, Thompson remained hesitant and was having trouble deciding between two people. After several minutes, she told the police that Cotton “looks the most like him.” The lead detective asked “if she was certain,” and she said, “Yes.” Again, the detectives further reinforced her decision. The lead detective told Thompson, “It’s the same person you picked from the photos.” She later described feeling a “huge amount of relief” when told that she had again picked the right person.

At Ronald Cotton’s criminal trial, Thompson agreed she was “absolutely sure” that he was the rapist. Cotton was sentenced to life in prison plus 54 years. He served 10.5 years before DNA tests exonerated him and implicated another man, Bobby Poole. Not only did the identification procedures increase Thompson's confidence in the mistaken memory event, but they also resulted in her rejection of the actual culprit. Poole had been presented to Thompson at a post-trial hearing, and she could not recognize him. “I have never seen him in my life,” she said at the time.

In response to this error, the lead detective in the case, Mike Gauldin, later as police chief, was the first in the state to institute a series of new practices, including double-blind lineup procedures. In the years that followed, North Carolina adopted such practices statewide. Ronald Cotton and Jennifer Thompson have since written a book, Picking Cotton, that describes their case and experiences.

____________

aSee, generally, http://www.cbsnews.com/news/eyewitness-how-accurate-is-visual-memory/ and http://www.slate.com/articles/news_and_politics/jurisprudence/features/2011/getting_it_wrong_convicting_the_innocent/how_eyewitnesses_can_send_innocents_to_jail.html.

be sizable. One estimate based on a 1989 survey of prosecutors suggests that at least 80,000 eyewitnesses make identifications of suspects in criminal investigations each year.5

Recently, post-conviction DNA exonerations of innocent persons have dramatically highlighted the problems with eyewitness identifications.6,7 In the United States, more than 300 exonerations have resulted from post-conviction DNA testing since 1989.8 According to the Innocence Project, at least one mistaken eyewitness identification was present in almost three-quarters of DNA exonerations.9 In many of these cases, eyewitness identification played a significant evidentiary role, and almost without exception, the eyewitnesses who testified expressed complete confidence that they had chosen the perpetrator. Many eyewitnesses testified with high confidence despite earlier expressions of uncertainty.10 For example, in the well-known case of Ronald Cotton (see Box 1-1), Jennifer Thompson (the victim) has described how she was initially quite unsure of her eyewitness identification of Cotton, a man later exonerated by DNA testing. She became certain it was Cotton only after the police made confirmatory remarks and had her participate in two identification procedures where Cotton was the only person shown both times.

Erroneous eyewitness identifications can occur across the range of criminal convictions in which eyewitness evidence is presented, but most of these cases lack the biological material that can be tested for DNA and used for exoneration purposes. While eyewitness misidentifications may have been a dominant factor in some erroneous convictions, it is important to note that other factors, including errors at various stages of the legal and judicial processes, may have contributed to the erroneous convictions.

CHARGE TO THE COMMITTEE

In 2013, the Laura and John Arnold Foundation called on the National Research Council (NRC) to assess the state of scientific research on

_______________

5A. G. Goldstein, J. E. Chance, and G. R. Schneller, “Frequency of Eyewitness Identification in Criminal Cases: A Survey of Prosecutors,” Bulletin of the Psychonomic Society 27(1): 71, 73 (January 1989).

6CNN, “Exonerated: Cases by the Numbers,” December 4, 2013, available at: http://www.cnn.com/2013/12/04/justice/prisoner-exonerations-facts-innocence-project/.

7Taryn Simon, “Freedom Row,” New York Times Magazine, January 26, 2003.

8The Innocence Project, “DNA Exoneree Case Profiles,” available at: http://www.innocenceproject.org/know/.

9The Innocence Project, “Eyewitness Identification,” available at: http://www.innocenceproject.org/fix/Eyewitness-Identification.php.

10Brandon L. Garrett, Convicting the Innocent: Where Criminal Prosecutions Go Wrong 63–68 (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2011).

BOX 1-2

Charge to the Committee

The charge to the NRC was to:

- critically assess the existing body of scientific research as it relates to eyewitness identification;

- identify any gaps in the existing body of literature and suggest, as appropriate, research questions to pursue that will further our understanding of eyewitness identification and that might offer additional insight into law enforcement and courtroom practice;

- provide an assessment of what can be learned from research fields outside of eyewitness identification;

- offer recommendations for best practices in the handling of eyewitness identifications by law enforcement;

- offer recommendations for developing jury instructions;

- offer advice regarding the scope of a Phase II consideration of neuroscience research as well as any other areas of research that might have a bearing on eyewitness identification; and

- write a consensus report with appropriate findings and recommendations.

eyewitness identification and to recommend best practices11 for handling eyewitness identifications by law enforcement and the courts. The goal of this effort was to evaluate the scientific basis for eyewitness identification, to help establish the scientific foundation for effective real-world practices, and to facilitate the development of policies to improve eyewitness identification validity in the context of the American justice system.

In response to this charge, the NRC appointed an ad hoc committee, the Committee on Scientific Approaches to Understanding and Maximizing the Validity and Reliability of Eyewitness Identification in Law Enforcement and the Courts (hereinafter, the committee), to undertake this study (see Box 1-2 for the committee’s charge). The committee met three times, held numerous conference calls, heard from various stakeholders (see Appendix B), and reviewed extensive research on eyewitness identification before reaching its findings and recommendations.

_______________

11For the purposes of this report, the committee characterizes best practice as the adoption of standardized procedures based on scientific principles. The committee does not make any endorsement of practices designated as best practices by other bodies.

SCIENCE AND LAW

Law enforcement officers investigating crimes rely on eyewitness identification procedures to verify that a suspect is the individual seen by an eyewitness.12 Such procedures can take place under conditions that may have significant effects on the accuracy and reliability of an eyewitness’ identification. Unlike officers in the field, laboratory researchers have, in theory, greater control over influences that might contaminate the visual perceptual experience and memory of an eyewitness.

Science is a self-correcting enterprise. Researchers formulate and test hypotheses using observations and experiments, which are then subject to independent review. In science, evidence and data are analyzed and experiments are repeated to ensure that biases or other factors do not lead to incorrect conclusions. Scientific progress results from the review and revision of earlier results and conclusions.

The culture of scientific research is markedly different from a legal culture that must seek definitive results in individual cases. In 1993, in Daubert v. Merrell Dow Pharmaceuticals, Inc., the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that, under Rule 702 of the Federal Rules of Evidence (which covers both civil and criminal trials in the federal courts), a “trial judge must ensure that any and all scientific testimony or evidence admitted is not only relevant, but reliable.”13

Criminal justice and legal personnel have come to rely on eyewitness evidence. Law enforcement officials have first-hand experience with eyewitnesses in criminal investigations and trials, and over the years, some juridictions have implemented and strengthened practices and procedures in an attempt to improve acccuracy. Consequently, the law enforcement and legal communities have made important contributions to our understanding of eyewitness identifications and the improvements of practices in the field. Researchers have become increasingly involved in assessing eyewitness identification procedures as law enforcement, lawyers, and judges have themselves sought more accurate procedures and approaches. In the 2009 National Research Council report, Strengthening Forensic Science in the United States: A Path Forward, the committee noted, “in addition to protecting innocent persons from being convicted of crimes that they did not commit, we are also seeking to protect society from persons who have

_______________

12For ease of reading, throughout the report the committee will use the term officer to mean law enforcement officials and professionals.

13Daubert v. Merrell Dow Pharmaceuticals, Inc., 509 U.S. 579 (1993). The Court also noted that “there are important differences between the quest for truth in the courtroom and the quest for truth in the laboratory. Scientific conclusions are subject to perpetual revision. Law, on the other hand, must resolve disputes finally and quickly.”

committed criminal acts.”14 This shared common goal of protecting innocent persons and society makes collaboration between the scientific, law enforcement, and legal communities critically important.

IDENTIFYING THE CULPRIT

Officers typically use three procedures to identify a perpetrator whose identity is unknown: (1) showups; (2) presentations of photo arrays; and (3) live lineups. A showup is a procedure in which officers present a single criminal suspect to a witness. This procedure usually occurs near the crime location and immediately or shortly after the crime has occurred. Officers also use photo arrays and live lineups, in which they ask the witness to view numerous individuals, one of whom may be the perpetrator. The suspect is presented along with fillers (known non-suspects). Currently, photo arrays are used more often than live lineups.15,16

If the eyewitness makes a positive identification during a showup, a photo array, or a lineup, the identification may constitute evidence about a suspect’s involvement in a crime. The eyewitness identification may, when considered with other available evidence, establish probable cause to support an arrest. Such evidence may play a pivotal role in enabling the prosecution to meet its burden of proof in a subsequent trial.

In recent years, more law enforcement agencies have created written eyewitness identification policies and have adopted formalized training. However, there are many agencies that do not have standard written policies or formalized training for the administration of identification procedures or for ongoing interactions with witnesses.17

VISION AND MEMORY

At its core, eyewitness identification relies on brain systems for visual perception and memory: The witness perceives the face and other aspects of the perpetrator’s physical appearance and bearing, stores that informa-

_______________

14National Research Council, Strengthening Forensic Science in the United States: A Path Forward (Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2009), p. 12.

15Police Executive Research Forum, “A National Survey of Eyewitness Identification Procedures in Law Enforcement Agencies,” March 2013, p. 48. The survey indicates that 94.1 percent of responding law enforcement agencies reported that they use photo arrays, while only 21.4 percent reported using live lineups. Sixty-one point eight percent of agencies reported that they use showups. See also J. S. Neuschatz et al., “Comprehensive Evaluation of Showups,” in Advances in Psychology and Law, ed. M. Miller and B. Bornstein (New York: Springer, in press).

16Throughout the report, unless otherwise specified, references to lineups refer to both photo arrays and live lineups.

17Police Executive Research Forum, p. 65.

tion in memory, and later retrieves the information for comparison with the visual percept of an individual in a lineup. Recent years have seen great advances in our scientific understanding of the basic mechanisms, operational strategies, and limitations of human vision and memory. These advances inform our understanding of the accuracy of eyewitness identification.

Human vision does not capture a perfect, error-free “trace” of a witnessed event. What an individual actually perceives can be heavily influenced by bias18 and expectations derived from cultural factors, behavioral goals, emotions, and prior experiences with the world. For eyewitness identification to take place, perceived information must be encoded in memory, stored, and subsequently retrieved. As time passes, memories become less stable. In addition, suggestion and the exposure to new information may influence and distort what the individual believes she or he has seen.

Several factors are known to affect the fidelity of visual perception and the integrity of memory. In particular, vision and memory are constrained by processing bottlenecks and various sources of noise.19 Noise comes from a variety of sources, some associated with the structure of the visual environment, some inherent in the optical and neuronal processes involved, some reflecting sensory content not relevant to the observer’s goals, and some originating with incorrect expectations derived from memory. The concept of noise has profound significance for understanding eyewitness identification, as the accuracy of information about the environment gained through vision and stored in memory is necessarily, and often sharply, limited by noise.

The recognition of one person by another—a seemingly commonplace and unremarkable everyday occurrence—involves complex processes that are limited by noise and subject to many extraneous influences. Eyewitness identification research confronts methodological challenges that some other basic experimental sciences do not encounter, as well as practical challenges

_______________

18Bias is defined as any tendency that prevents unprejudiced consideration of a question (see Dictionary.com; http://dictionary.reference.com/browse/bias). Response bias is a general term for a wide range of influences that moderate the responses of participants away from an accurate or truthful response. Response bias can be induced or caused by a number of factors, all relating to the idea that humans do not respond passively to stimuli, but rather actively integrate multiple sources of information to generate a response in a given situation [(see M. Orne, “On the Social Psychology of the Psychological Experiment: With Particular Reference to Demand Characteristics and Their Implications,” American Psychologist 17: 776–783, (1962)]. In research, bias is seen in sampling or testing when circumstances select or encourage one outcome or answer over another (see Merriam-Webster.com; http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/bias).

19Noise refers here to factors that cause uncertainty on the part of an individual about whether a particular signal (e.g. a specific visual stimulus) is present. This use of the term follows the definition used in electronic signal transmission, in which noise refers to random or irrelevant elements that interfere with detection of coherent and informative signals.

in establishing adequate experimental controls over the numerous variables that affect visual perception and memory.

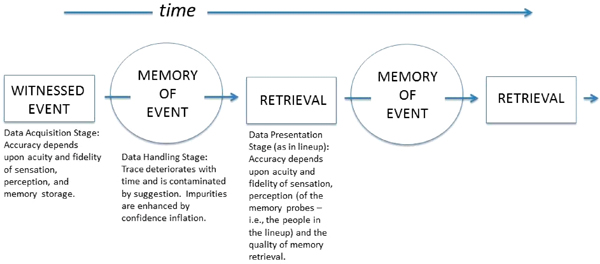

APPLIED RESEARCH ON EYEWITNESS IDENTIFICATION: SYSTEM AND ESTIMATOR VARIABLES

Our understanding of the underlying processes and limits of eyewitness identification, derived from basic research on vision and memory, is complemented by research directed specifically at the problem of eyewitness identification. The modern era of eyewitness identification research began in the 1970s. Today, eyewitness identification is generally viewed as a behavioral output. The accuracy and reliability of eyewitness identification are critically modulated by variables that include a witness’ extant cognition and memory and related psychological and situational factors at the time of the event, over the ensuing intervals, and at all stages of recall (see Figure 1-1). Because a crime is an unexpected event, one can draw a natural distinction between variables that reflect the witness’ unplanned situational or cognitive state at the time of the crime and the variables that reflect controllable conditions and internal states following the witnessed events. Researchers categorize these factors, respectively, as estimator variables and system variables.20

System variables describe the characteristics of specific procedures and practices (e.g., the content and nature of instructions given to witnesses who are asked if they are able to make an identification). The criminal justice system can exert some control over system variables by following standardized procedures that are based on scientific knowledge and strengthened through education and training.

One important category of system variables concerns the conditions and protocols for lineup identification. Under current law enforcement practice, eyewitness identification procedures involve having a witness view individuals or images of individuals. Research indicates that accuracy and reliability of eyewitness identifications may be influenced by the type of presentation (e.g., lineup) used, the likeness of non-suspect lineup participants (fillers) to the suspect, the number of fillers, and the suspect’s physical location in the presentation.21,22 Eyewitness performance may be affected by how the lineup images are presented—simultaneously (as a group) or

_______________

20G. L. Wells, “Applied Eyewitness-Testimony Research: System Variables and Estimator Variables,” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 36(12):1546–1557 (1978).

21N. K. Steblay et al., “Eyewitness Accuracy Rates in Police Showup and Lineup Presentations: A Meta-Analytic Comparison,” Law and Human Behavior 27(5): 523–540 (October 2003).

22R. J. Fitzgerald et al., “The Effect of Suspect-Filler Similarity on Eyewitness Identification Decisions: A Meta-analysis,” Psychology, Public Policy, and Law 19(2): 151–164 (May 2013).

FIGURE 1-1 Memory accuracy and time.

SOURCE: Courtesy of Thomas D. Albright.

sequentially (one at a time). System variables, such as the nature of the instructions and feedback provided before and after the identification procedure, may also affect the eyewitness’ identification.

Estimator variables affect the accuracy of eyewitness identification, but they are beyond the control of the criminal justice system. Estimator variables tend to be associated with characteristics of the witness or factors that are operating either at the time of the criminal event (perhaps relating to memory encoding) or the retention interval (the time between witnessing an event and the identification process). Specific examples include the eyewitness’ level of stress or trauma at the time of the incident, the light level and nature of the visual conditions that affect visibility and the clarity of a perpetrator’s features, and the physical distance between the witness and the perpetrator. Both system and estimator variables will be discussed in detail in subsequent chapters.

EFFORTS AT IMPROVEMENT

In response to insights gained from research on erroneous convictions, there have been attempts to provide recommendations for improving the reliability and validity of eyewitness identifications. An effort of particular note is the National Institute of Justice’s (NIJ) Technical Working Group for Eyewitness Evidence (TWGEYEE). Called together by then-U.S. Attorney General Janet Reno in 1998, members of the working group were asked to develop and publish guidance for improving eyewitness identification

procedures.23 The working group recognized the role that memory plays in the mistaken interpretation and remembrance of events and offered guidance based on the practical experiences of the law enforcement community and insights gained from behavioral and psychological research. The NIJ provided detailed instructions for each step of the eyewitness identification procedure to the approximately 18,000 state and local law enforcement agencies across the nation. After the report was issued, only a few states conducted evaluations and engaged in improvement efforts, including the implementation of new laws and the issuance of corrective guidelines and policies. Consequently, eyewitness identification policies remain fragmented by jurisdiction, except in a minority of states that have adopted state-wide policies. At present, the United States does not have a uniform national set of protocols.24

JUDICIAL CONSIDERATION OF EYEWITNESS IDENTIFICATION EVIDENCE

The U.S. Supreme Court’s 1977 ruling in Manson v. Brathwaite provides the current framework for judicial review of eyewitness identification under the Due Process Clause of the U.S. Constitution.25 The Manson v. Brathwaite test asks judges to evaluate the “reliability” of eyewitness identifications using factors derived from prior rulings and not from empirically validated sources. The Manson v. Brathwaite ruling was not based on much of the research conducted by scientists on visual perception, memory, and eyewitness identification, and it fails to include important advances that have strengthened standards for judicial review of eyewitness identification evidence at the state level.

In 2011, the Justices of the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court convened the Study Group on Eyewitness Identification to “offer guidance as to how our courts can most effectively deter unnecessarily suggestive identification procedures and minimize the risk of a wrongful conviction.” The report made five recommendations to minimize inaccurate identifications: (1) acknowledge variables affecting identification accuracy; (2) develop a model policy and implement best practices for police departments; (3) expand use of pretrial hearings; (4) expand use of improved jury instructions; and (5) offer continuing education.26

_______________

23U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Eyewitness Evidence: A Guide for Law Enforcement (Washington, DC, 1999).

24Police Executive Research Forum, p. 65.

25Manson v. Brathwaite, 432 U.S. 98, 114 (1977).

26Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court Study Group on Eyewitness Identification, Report and Recommendations to the Justices, July 24, 2013, available at: http://www.mass.gov/courts/docs/sjc/docs/eyewitness-evidence-report-2013.pdf.

In 2011, the New Jersey Supreme Court issued a unanimous decision in State v. Larry R. Henderson. The opinion revised the legal framework for evaluating and admitting eyewitness identification evidence and directed that improved jury instructions be prepared to help jurors evaluate such evidence. Henderson drew on an extensive review of scientific evidence regarding human vision, memory, and the various factors that can affect the reliability of eyewitness identifications. In July 2012, the court released expanded jury instructions and revised court rules relating to eyewitness identifications in criminal cases.27

In fall 2012, the Oregon Supreme Court also established a new procedure for evaluating whether eyewitness identifications could be used in court. In State v. Lawson, the Court reviewed eyewitness identification research conducted over the past 30 years, determined that the Manson v. Brathwaite test “does not accomplish its goal of ensuring that only sufficiently reliable identifications are admitted into evidence,” and offered a revised procedure that requires the court to make a determination of whether investigators used “suggestive” tactics to get an identification and the extent to which other information supports the identification.28

Despite these improvements and judicial decisions, policies and practices across the country remain inconsistent.

ORGANIZATION OF THE REPORT

This report begins with a description of law enforcement protocols for eyewitness identification (Chapter 2). Chapter 3 presents the legal framework for eyewitness identification evidence. A discussion of the current scientific understanding of visual perception and memory follows in Chapter 4. In Chapter 5, the committee provides an assessment of eyewitness identification research. The report concludes with the committee’s findings and recommendations (Chapter 6).

_______________

27New Jersey Judiciary, “Supreme Court Releases Eyewitness Identification Criteria for Criminal Cases,” July 19, 2012, available at: http://www.judiciary.state.nj.us/pressrel/2012/pr120719a.htm.

28State v. Lawson, 352 Or. 724 (Or. 2012).