The United States’ Strategic Imperative to Invest in Health Systems

The WHO has described the health system as, “the sum total of all the organizations, institutions, and resources whose primary purpose is to improve health” (WHO, 2005). As such, the health system includes much more than the health care delivery system, though this distinction can get lost in policy discussions. The WHO has identified six building blocks of a health system:

- the leadership, who steer the health sector and set the country’s policies;

- the information system that supports vital registration, surveillance, and monitoring, financing, human resources, coverage, and quality of care;

- an accountable financing system to raise and pool funds;

- a productive workforce and tools to ensure they are deployed efficiently;

- an affordable supply of essential medicines, vaccines, and technology and a functional regulatory authority to protect their quality;

- and, lastly, a service delivery system that can work through public or private sector providers (WHO, 2007a, 2010a).

The health system is a social institution. It produces a set of essential public health functions, things like disease surveillance, medicines regulation, research, and policies (Khaleghian and Gupta, 2005). Curative and preventative health care are a part, but only a part, of the health system’s essential services (CDC Office for State Tribal Local and

Territorial Support, 2014). The health system is the foundation supporting effective health services.

A TRADITION OF SUPPORTING GLOBAL HEALTH

Health assistance is usually described as either vertical (or categorical, targeted programs) with systems dedicated to specific service or condition, or horizontal (or integrated programs), which support more comprehensive care. Vertical programs generally have separate management and logistics systems: this can include a separate workforce, surveillance system, and method of assuring drug quality (Victora et al., 2004). Horizontal programs, on the other hand, tend to work more generally through primary care systems (Sepúlveda et al., 2006; Victora et al., 2004). In practice, the distinction between vertical and horizontal health programs is not always clear; most services have a range of vertical and horizontal elements (Atun et al., 2008; Oliveira-Cruz et al., 2003). For example, immunizations delivered though primary care may be paid for with vertical, donor financing. Conversely, immunizations may be paid for from the general health budget, but provided at free-standing vaccine clinics or on vaccine campaign days (Atun et al., 2008).

Over time, donor interest in relatively more vertical or horizontal health aid has fluctuated. In 1988, Carl Taylor and Richard Jolly decried an emerging battle in development assistance between proponents of selective and comprehensive primary care (Taylor and Jolly, 1988). They concluded that functional health systems have both selective, or vertical, elements, and comprehensive, or horizontal, ones (Taylor and Jolly, 1988). Nevertheless, they cited “abundant experience” of vertical programs that have, “been started at the insistence of international donors so that they can monitor the flow of their dollars and take credit for their impact … leav[ing] countries with entrenched bureaucracies that resist eventual integration into [primary health care]” (Taylor and Jolly, 1988, p. 975). They acknowledged the value of technological innovations, but cautioned that these technologies would “not make much difference” without attention to organization, management, financing, and the training health personnel (Taylor and Jolly, 1988, p. 973). They also identified an “urgent question” for future debate: how to develop a sustainable infrastructure for primary care in developing countries (Taylor and Jolly, 1988, p. 975).

Their concerns are as relevant today as they were 26 years ago. Vertical health programs have continued to enjoy some popularity among donors. Such arrangements work well when there is urgent need to respond to an epidemic or when international cooperative action is necessary for success (Peters et al., 2013b; Victora et al., 2004). Smallpox was eradicated in 1980 through an international, vertical health program (Atun et al., 2008; WHO, 2010d). More recently, the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) has brought lifesaving treatment to 6.7 million people in 65 countries (PEPFAR and Department of State HIU, 2014). At times, however, the free-standing structure of the vertical program can impede success. Malaria eradication efforts, for example, may have failed because case surveillance was not integrated into primary care (Atun et al., 2008; Bradley, 1998). There are also concerns with negative spillover effects of vertical programs: they create a hierarchy of diseases, encourage fragmentation, are often inefficient (Atun et al., 2008). Most of all, as Taylor and Jolly pointed out, vertical initiatives depend on dedicated funding and specialized management (Taylor and Jolly, 1988). They are designed for donor funding needs, and are not typically sustainable when outside funding ends.

Experts have debated the merits of vertical and horizontal health strategies for decades, but there is remarkably little scientific analysis on their relative effectiveness (Atun et al., 2008). It is clear, however, that vertical programs attract funding in places with weak health infrastructure and poor public management (Victora et al., 2004). When these programs are then run in a way that undermines the local health system, the initial management and infrastructure problems are not likely to improve. To put it another way, failure to plan for the careful integration of vertical programs with general health services aggravates the very staffing and organizational constraints that made foreign assistance necessary in the first place.

The future of global health will require building off established platforms, integrating HIV, tuberculosis, malaria, and maternal and child health programs with primary care systems, using targeted investments to improve the broader health infrastructure countries’ depend on (Atun et al., 2013; Samb et al., 2009). In an era when donors aim to speed progress to health goals, duplicating pieces of the health system for vertical programs will not be a sustainable or sensible strategy.

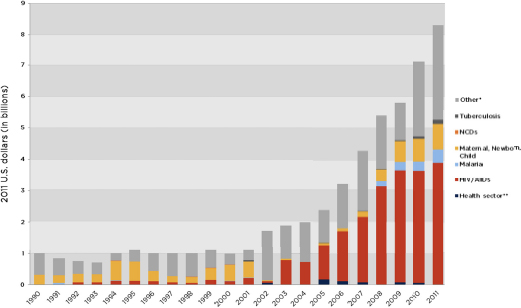

FIGURE 2-1 U.S. Bilateral Assistance for Health by Focus Area, 1990-2011.

* Other includes all development assistance for health that does not fall within any of the six categories tracked by the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation. Programs included in this category include road traffic safety and neglected tropical diseases.

** Health sector assistance is that given directly to developing country governments to spend on health system strengthening.

SOURCE: IHME, 2014.

A concern with sustainability, the ability of a project to function effectively after outside support comes to an end, takes particular precedence now, as aid recipient countries are increasingly able to fund health services independently (WHO African Programme for Onchocerciasis Control, 2014). Sustainability and judicious integration of vertical programs with health systems are especially salient topics for the U.S. government, whose investment in health has grown over the past 25 years. Much of this spending is directed to targeted programs for maternal and child health, malaria, tuberculosis, and, most of all, HIV and AIDS. (See Figure 2-1.) PEPFAR, the U.S. government’s flagship program in global health, has driven much of this increase and accounts for about half of its bilateral health aid (IHME, 2014). PEPFAR has helped stem the tide of the HIV epidemic and averted a humanitarian and political catastrophe. The success of this program alone compels a thoughtful appraisal of the United States’ continued work in global health. In 2013, Secretary of State John Kerry lauded the birth of the millionth child protected from the vertical transmission of HIV because of PEPFAR (PEPFAR, 2013a). This child’s future, already inextricably linked to the United States, will depend on a functional health system to support a healthy life. Through prompt and judicious development action, the United States can help provide this.

This chapter will discuss the value of transformative investment in health systems, emphasizing why such action is necessary now, and why it is in the best interest of the United States. The first section discusses the timeliness of health systems building. Years of successful action against communicable disease, especially against HIV and AIDS, drive an urgency to the need for stronger health systems. Global epidemiological and economic changes are at work to the same end. Economies are growing around the world and people are living longer. Donors need to respond to this success with a revision in their aid strategy. There is a unique opportunity to take stock of foreign aid now, as countries set development goals for 2015 and later. Next, the chapter will discuss the relationship between strong health systems and good health, prosperity, and security around the world.

Key Finding

- Health assistance is usually described as either vertical or horizontal. Vertical programs are targeted to a specific disease or service; horizontal ones support more comprehensive care. Donors tend to value vertical health programs because of their immediate, but less sustainable, effects.

Conclusion

- When donors run vertical programs in a way that undermines the partner country’s health system, or when they fail to integrate vertical programs with general health services, they only aggravate their partner countries’ staffing and organizational problems.

ATTENTION TO HEALTH SYSTEMS CANNOT WAIT

There is pressing need for deliberate and prompt investment in health systems in low- and middle-income countries. The urgency of this need stems in part from the natural progression of decades of vertical health programming to strengthen curative and preventative services; larger demographic and political trends drive the rest. Deliberate and thoughtful action now can help ensure the success and sustainability of the U.S. government’s targeted health investments.

Sustaining the Investment in HIV and AIDS

The U.S. taxpayer supported $7.4 billion dollars in bilateral aid for health in fiscal year 2014. Adding contributions made through multilateral and charitable organizations raises the total by about a quarter (IHME, 2014). The vast majority of this spending (75 percent for much of the 2000s) was dedicated to HIV and AIDS programs (Emanuel, 2012). The returns on this investment have been substantial. The first cycle of PEPFAR averted roughly 1.2 million deaths and contributed to the 19 percent reduction in HIV transmission (UNAIDS, 2010; Walensky and Kuritzkes, 2010). These early successes have allowed for a new target: eliminating new HIV cases in children by 2015, with a longer goal of eventually halting all transmission of the virus, ushering in an AIDS-free generation (Office of the Global AIDS Coordinator, 2012).

In the early days of PEPFAR, the program’s staggering logistics posed the biggest obstacle. The past decade has shown that it is possible to bring good quality antiretroviral drugs and the necessary supportive care to patients in remote places. The program is no longer in its emergency response phase. The next stage is in many ways more complicated—it depends on building technical depth in recipient countries (Bendavid and Miller, 2010; IOM, 2013). It will not be possible to halt HIV transmission or see an AIDS-free generation without systemic changes to the organization of health services. The 2013 PEPFAR strategy document acknowledges this, calling for increased ownership from partner country governments (Office of the Global AIDS Coordinator, 2012). This report emphasizes the importance of sharing the responsibility for AIDS programs and supporting countries to develop comprehensive health financing plans and systems for financial accountability (Office of the Global AIDS Coordinator, 2012).

PEPFAR began as a program with a relatively narrow, if ambitious, mandate to bring antiretroviral therapies to the world’s poorest AIDS patients and prevent the spread of HIV in their communities. This was extremely successful, and its success will have consequences for the U.S. and developing country governments (IOM, 2013). The patients who, through American generosity, avoided an early AIDS death are now facing lifetimes managing HIV as a chronic disease. They will have to deal with the long-term comorbidities of HIV while facing the routine morbidities of aging, all of which depends on decent primary care and the underpinnings of a reliable health infrastructure. The purpose of prolonging lives threatened by HIV was not to lose them 10 years later to diabetes, also a gruesome and expensive disease. While the U.S. government cannot and should not fund treatment for every health problem as PEPFAR has done for HIV and AIDS, a responsibility to these patients will influence its future involvement in global health.

Foreign policy is shaped in part by the current social and political climate, and is partly predetermined by the trajectory of commitments already made. Attention to the management, financing, and infrastructure that support health services in poor countries is a priority by either calculation. A functional health system is the most important prerequisite to maintain ground against the HIV epidemic in Africa. A stronger health system in poor countries is also the best insurance against a complicated and changing future burden of disease. Finally, a stronger health system reduces the future dependence of low- and middle-income countries on foreign aid.

Epidemiological Transitions

The burden of disease in developing countries is not just changing; it is changing in a way that history has not prepared us for. What demographers call the epidemiological transition, a shift in population-level causes of illness and death from infectious to chronic disease, took more than 100 years in western Europe (Omran, 2005). This process happens both more quickly and less directly in countries that started later (Kengne and Mayosi, 2014; Santosa et al., 2014). In the Micronesian island of Nauru, for example, diabetes, road traffic accidents, and circulatory disorders became prominent so suddenly and (especially with road traffic injuries) among the young, as to obscure any noticeable improvement in lifespan from reducing infectious disease (Santosa et al., 2014; Schooneveldt et al., 1988).

More often poor countries cope with the dual burden of infectious and chronic diseases in different sub-populations. Maternal and child mortality are much higher in South and Southeast Asia and sub-Saharan Africa than in the rest of the world, largely because the poorest people have remained outside the reach of the health system (WHO, 2014d; WHO et al., 2014). These same places have growing epidemics of cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and the co-morbidities of obesity. Now the differences in burden of disease are as pronounced within countries as among them. Different social classes have widely different lifestyles, diets, and access to health services, leading to an epidemiological polarization, the co-existence of both modern and ancient patterns of disease among different groups in the same country (Frenk et al., 1989).

Meanwhile, urbanization, which increases growth and access to health services, has contributed to a protracted epidemiological shift where problems of hunger and infection linger in the same community, even the same household as the so-called diseases of affluence (things like stroke, hypertension, chronic heart and kidney disease, and diabetes). Rural to urban migration has abruptly changed meal patterns and diet. Emigrants to cities no longer raise their own food, nor do they necessarily have common mealtimes. Cities offer women opportunities in the paid workforce, precluding extended breast feeding and leaving less time to cook. Packaged foods and vegetable fats are the cheapest and easiest way to eat. Such a diet will drive adults to obesity and its manifold co-morbidities, but provide little protein or appropriate weaning nutrition to children, who then fail to grow (Agyei-Mensah and de-Graft Aikins, 2010; Caballero, 2005). Starvation in utero and early

childhood triggers a process of metabolic compensation that puts the underweight child, ironically, at increased risk of obesity in adulthood (Barker, 2012; Caballero, 2005). For all these reasons, the WHO reckons that adults under 70 in poor countries are more likely to die from a noncommunicable disease than their counterparts in rich ones (WHO, 2014c).

The health effects of globalization and climate change only complicate the picture. Poor countries struggle with industrial pollution, putting people at higher risk of chronic diseases like asthma (Shiru, 2011). The effects of climate change, felt harder close to the equator, will introduce vector-borne disease such as malaria and dengue to higher altitudes (McMichael, 2000; Miranda et al., 2011). More intense rainstorms could lead to a longer breeding season for mosquitoes (McMichael, 2000). At the same time, the worldwide threat of infectious epidemics has not receded as much as the classic epidemiological transition would have predicted. Anti-microbial resistance and globalization have contributed to the emergence of new pandemic viruses, such as H5N1 avian influenza (Santosa et al., 2014).

A tidal wave of health problems is pressing down on the developing world. Preparedness for these changes is understandably poor. A recent study in Tanzania found that, with the exception of HIV services, care for chronic diseases, such as hypertension, diabetes, and epilepsy, was woefully inadequate (Peck et al., 2014). Staff at the health posts and dispensaries closest to patients were not informed on how to manage these conditions; less than half of the nurses surveyed had even a fair knowledge of diabetes care, though 79 percent were competent to manage HIV (Peck et al., 2014). Even if the workers were better trained, diagnostic equipment and medicines were scarce. Thirty percent of the primary health posts visited did not even have a functional scale (Peck et al., 2014).

It is difficult to say what portion of the problem in the Tanzania study is specific to the challenge of noncommunicable disease care and how much is a reflection of a broader problem in the health system (Kengne and Mayosi, 2014). Either way, it is a reminder that shifting patterns of illness in poor countries are overwhelming the health infrastructure. Ministers of health in poor countries face increasingly complicated trade-offs: between preventative and curative services, between treating children and adults, and among different ways to pay for health. There is still time to manage these trade-offs, but decisions need to be made before the full force of the chronic disease epidemic hits

the poorest countries. There are investments in health technology and the drug supply chain, for example, that can improve treatment for a range of conditions. In the opinion of this committee, directing foreign assistance at these kinds of systemic improvements is an efficient way for donors to help aid recipients prepare for the inevitably changing patterns of health and illness.

Economic and Demographic Changes

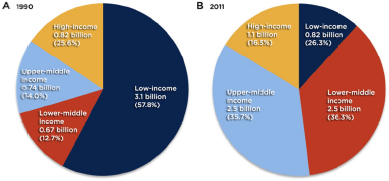

The past 25 years have seen tremendous global growth; almost a billion people have escaped extreme poverty1 (Poverty: Not always with us, 2013). Their national economies have improved at the same time. In 1990, 57.8 percent of the world lived in what the World Bank classifies as a low-income country; by 2011, only 11.7 percent did (see Figure 2-2) (Jamison et al., 2013). Increasing national incomes mean a broader tax base, and governments have made commensurate improvements in their ability to collect revenue. Tax revenue as a percentage of gross domestic product (GDP) increased by four percentage points between 1990 and 2011 in low- and lower-middle-income countries, and by 6 percentage points in upper-middle income countries (Jamison et al., 2013). A broadening tax base will mean decreasing prominence of donor assistance for development. At the same, donor assistance has declined. The 2008-2009 financial crisis reduced the amount of aid money available; by 2011, growth in bilateral development assistance for health had slowed to its lowest annualized rate since 2001 (Leach-Kemon et al., 2012).

The growth of middle-income countries is something to celebrate, but important disparities often hide beneath the aggregate improvements. Most of the billion people left in dire poverty, by some estimates 75 percent of them, live in middle-income countries (Sumner, 2010; UN System Task Team, 2012). Using development assistance to change their lives is complicated. Foreign aid is becoming less welcome in emerging economies, most notably in India and China, two countries that together account for slightly less than half of the world’s poorest people (Mohanty, 2012; Olinto and Uematsu, 2013). The challenge for the future of development is to use our remaining influence and a proportionately decreasing share of national budgets, to benefit the most

___________________________

1 Defined by the World Bank as <$1.25 a day, adjusted for 2005 purchasing power parity (Ravallion et al., 2008).

FIGURE 2-2 Movement of populations from low income to higher income between 1990 and 2011. Data refer to classifications based on (A) 1990 and (B) 2011 gross national income per head that were the basis for the World Bank’s lending classifications for its financial year 1992 and financial year 2013, respectively. The World Bank did not classify all countries into income groups. Countries that were unclassified in either 1990 or 2011 were removed from the calculations.

SOURCE: Reprinted from The Lancet, 382, Jamison, et al., Global health 2035: A world converging within a generation, pp. 1898-1955, Copyright 2013, with permission from Elsevier.

vulnerable. As WHO Director-General Margaret Chan observed, “the health needs of the poor can be met by national budgets, this does not necessarily mean that they will be” (Chan, 2013, p. e35).

Meeting these needs will only get more difficult in the future. Today, as many as a third of the world’s poorest people live in fragile states, places like Somalia and the Democratic Republic of the Congo (Chandy et al., 2013). In 4 years’ time that share could rise to half and by 2030, to two-thirds (Chandy et al., 2013). This changing demographic drives what the Economist describes as the donor’s dilemma: “middle-income countries do not really need aid, while fragile states cannot use it properly” (Poverty: Not always with us, 2013). The overstatement of this position is debatable, but it is clear that fragile states have, almost by definition, little service infrastructure and intense political volatility (Ralston, 2014). When donor aid to these countries fluctuates widely from year to year, it can aggravate instability (Chandy, 2011). Health aid for fragile states often comes as humanitarian relief without links to longer-term health systems development (Farmer, 2013; Hill, 2014).

In any case, the donor’s dilemma will force the United States, like all governments and organizations working in development, to re-evaluate

its aid strategy. The solution lies in identifying investments that transform lives for the people suffering the brunt of ill health and early death. To start, this means investing in health not just health services. In a letter to The Lancet, 16 ministers of health and foreign affairs and heads of global public health organizations explained that the future of global health lies in, “governance, management, and leadership to address inequalities, reach the most vulnerable and marginalized people, and create an enabling policy and legal environment” (Engström et al., 2013, p. 1862).

There is a window of time now when such transformative investment is not only possible but affordable. Stenberg and colleagues (2014) recently modeled the costs to support health systems, maternal and newborn health, pediatrics, immunization, family planning, HIV and AIDS, and malaria against their returns as measured by social and economic benefit to society. They found that a 2 percent increase in current spending for health could, over 30 years, yield nine times that value, not just in terms of an estimated 184 million lives saved, but in workforce participation, smaller family size and lower dependency rates, and increased savings, investment, and workforce productivity. Their models called for a substantial initial investment to health systems and the training of another 675,000 doctors, nurses, and midwives by 2035. The returns will come more slowly; many projected benefits cannot be realized until 2050 or later, as they affect the growth and development of infants and children who will not enter the workforce for decades (Stenberg et al., 2014). Regardless, aid for health still offers one of the best returns on investment available (Gates and Gates, 2014). As with most investments, rewards come from early action and a long time horizon.

The Post-2015 Development Agenda

Improving systemic effectiveness in poor countries, increasing social protection, and setting up resilient local management are important themes in post-2015 development discussion (OECD, 2013a; UN Open Working Group on Sustainable Development Goals; UN Secretary-General’s High-Level Panel of Eminent Persons on the Post-2015 Development Agenda, 2013; UN System Task Team, 2013). These are not necessarily new ideas. The 1993 World Development Report Investing in Health also emphasized efficiency, encouraging attention to the interventions that give the best value for their cost (World Bank,

1993). The report recommended that a publicly financed basic package of essential services be available in all countries, and that increased donor aid should be used to meet this goal. Twenty years later, there is new enthusiasm for the same idea, now framed as the movement towards universal health coverage.

Donors would do well to invest in the infrastructure that will support universal health coverage in developing countries. Their investment would yield considerable returns to the world economy, and will have a substantial diplomatic value beyond that. As donors’ proportional contribution to health spending in developing countries decreases, it will be more important to use donor influence judiciously. For the U.S. government this will mean making investments that reflect American values, including compassion for the most vulnerable.

Health diplomacy, a term used to describe diplomatic efforts to advance international cooperation on health, has the potential to generate goodwill, as it has done in the 65 PEPFAR recipient countries (Bendavid and Miller, 2010; U.S. Department of State). By the same token, there would be a serious reputational risk to the United States if any of the health gains we helped underwrite with PEPFAR were to be lost now. Such a loss is possible as long as deficiencies in national health systems prevent countries from managing the program effectively. In the opinion of this committee, a modest increase in spending and a few, judicious changes to the U.S. government’s aid strategy would help keep as friends a growing and dynamic group of low- and middle-income countries. This action could have substantial payoffs in developing a more stable and prosperous world.

Key Findings

- Countries with high child and maternal mortality also have growing epidemics of cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and obesity. The shifting patterns of illness are overwhelming the health systems in poor countries.

- Global economic growth has created a broader tax base in developing countries, making donor assistance a proportionately smaller piece of national funding for health.

- Using development aid to help the billion people left in dire poverty is complicated. Many of them live in increasingly self-sufficient middle-income countries or in fragile states, where political volatility makes them hard to reach.

Conclusions

- The success of the PEPFAR program alone compels thoughtful appraisal of the U.S. government’s continued work in global health. It will not be possible to maintain the ground against the HIV and AIDS epidemic without attention to the management, financing, and infrastructure that support health services.

- There would be a serious reputational risk to the United States if any of the health gains of PEPFAR were to be lost now. Such a loss is possible as long as deficiencies in national health systems prevent countries from taking effecting ownership of HIV and AIDS care.

- Helping the poor requires transformative investments in health, not just health services. The United States should support the infrastructure underlying universal health coverage in developing countries.

FUNCTIONAL HEALTH SYSTEMS ABROAD ENCOURAGE HEALTH, PROSPERITY, AND SECURITY

Foreign aid has humanitarian, political, and development purposes; aid directly for global health serves all three (Bread for the World, 2010). The United States supports health in poor countries because it is a moral obligation and because health has an intrinsic value (IOM, 2009). Improving health abroad is also a wise investment to spur short- and long-term growth. There is an immediate dividend from deaths and illness averted, and delayed gains when healthy children grow up and contribute to their societies. Their health is of direct benefit to their home countries and of larger benefit to building a more stable, peaceful world.

The epidemiological and demographic changes described in the previous section drive a need for donors to support health in developing countries, investing in the entire infrastructure, not just pieces of service delivery. Congress needs to consider support for health systems as an investment in health, prosperity, and global security.

Improving Health

U.S. action in global health has long addressed interventions, the pieces of clinical care that most immediately prevent death. Low- and middle-income countries may be approaching a point of diminishing marginal returns on such investments. Effective clinical medicine depends on a service infrastructure. While there is no one blueprint for how this infrastructure should look, there are certain common organizational features of good health systems (Mills, 2014). In an analysis of five parts of the world (Bangladesh; Ethiopia; Kyrgyzstan; Tamil Nadu, India; and Thailand) that have made better progress in health than their economically and geographically similar neighbors, Balabanova and colleagues (2013) identified political commitment, effective management and regulation, and the ability to adapt to limited resources as common precursors for success. Boxes 2-1, 2-2, and 2-3 give examples of innovative systemic changes that have improved health indicators or service delivery in poor countries.

Dysfunctional Health Systems Spread Disease, Good Health Systems Prevent It

Organization is often the biggest challenge in delivering health. The failure to control and treat tuberculosis in much of the former Eastern Bloc, for example, is primarily an organizational failure. The Soviet health system had four vertical programs for tuberculosis control: the penitentiary system, X-ray screening services, hospital care, and primary care. All four programs had separate management and funding streams; there was no sharing of staff or funding among programs (Atun and Coker, 2008). Treatment protocols called for lengthy hospital stays, not only wasting money and roughly 80,000 allocated hospital beds in Russia alone, but encouraging hospital-acquired tuberculosis (Atun and Coker, 2008; Atun et al., 2005a). The Soviet system persisted even after donors implemented DOTS,2 the WHO standardized treatment.

___________________________

2 Directly Observed Treatment, Short-course.

BOX 2-1

Hospital Reform in Kyrgyzstan

Kyrgyzstan inherited a Soviet health system that relied on hospitals for most treatment. Much public health spending went to fixed hospital costs and, despite having 429 doctors per 100,000 people in 1990, the primary care system was neglected and community health workers poorly trained. The system depended on revenues from Moscow, and was not viable after independence. Beginning in 1996, Ministry of Health reforms dramatically restructured health delivery to strengthen the Kyrgyz system.

Closing hospitals was central to these reforms. Under the Soviet system, a hospital’s funding was based on its number of beds, a system that gave no incentives for preventative services. The reforms shifted to payment for performance, and rewarded faster patient turnover. Fewer hospitals could then serve the same number of patients, so 42 percent of hospitals closed between 2000 and 2003. The money saved from keeping half-empty hospitals open was used on drugs, food, and supplies, as well as improvements to primary care.

The reforms shifted health care to an outpatient system, requiring commensurate shifts in the workforce. The WHO and USAID supported the government to emphasize family practice in the medical education, both in medical school curricula and with continuing medical education. Community health posts, remnants from the Soviet era, were revamped and their staff retrained. These posts helped meet the increased demand for primary care, particularly in rural areas, where hospitals had closed.

The reforms allowed for nearly universal coverage in essential primary services, and drove improvements in health outcomes. Between 1997 and 2006, infant mortality fell by nearly 50 percent and under-five mortality fell by over a third. Adult mortality rates also improved. Life expectancy in Kyrgyzstan has risen since the mid-1990s and is higher than in the wealthier Kazakhstan and half a year higher than in Russia, where per capita gross national income is 13 times greater.

SOURCES: Balabanova et al., 2013; Ibraimova et al., 2011; Kutzin et al., 2009; WHO Regional Office for Europe, 2013.

Research in Russia indicates that clinicians and patients resisted DOTS, seeing it as a foreign imposition (Atun et al., 2005a). The program took off poorly. The Russian payment structure directly contradicted the DOTS protocol, rewarding surgery and inpatient treatment regardless of whether the patient recovered (Atun et al., 2005b). By 2003, DOTS coverage in Russia was roughly 35 percentage points lower than in other countries with a similar disease burden (Atun

et al., 2005a). As of 2012, Russia had a tuberculosis incidence of 91 per 100,000, a figure that has declined relatively little since the 2000s, and parts of the country now report the world’s highest rates of multi-drug resistant tuberculosis (WHO, 2010c, 2012a).

Tuberculosis control in Russia has not floundered because of a problem with DOTS, an elegant strategy that has helped control the disease in much of the world. The problem stems from bottlenecks in the national health system and a failure to integrate four competing vertical programs and a primary care system (Atun et al., 2010). It is also a cautionary example of how narrow, disease-specific health programs can

BOX 2-2

Grassroots Management and Health Worker Expansion in Ethiopia

Despite being one of the poorest countries in the world, Ethiopia is working towards a goal of universal primary care by 2017. The national strategy relies heavily on district health offices to plan and manage the delivery and financing of primary care. District officials are encouraged to choose suitable, local priorities and manage their budget to meet them.

The district system relies on reliable data and organization. Every district health office keeps family health folders containing demographic information and patient histories organized by household. Health extension workers manage the folders and feed the household data into a national health information system. These data inform district and federal health plans, making both more responsive to local realities, and allow for modern disease surveillance and monitoring.

District officials also manage the national Health Extension Programme, which trains local women to provide basic primary care. Though Ethiopia has only 2-3 doctors, nurses, and midwives for every 10,000 people, health extension training brought an additional 30,000 health workers to rural districts in 5 years. District health offices tailor the health worker trainings to suit local needs and, because the trainees are chosen from the communities they work in, they are well received by their clients.

District health planning and delivery has helped increase access to health posts from 38 percent in 1991 to 89 percent in 2011. Health outcomes are also improving. Between 1997 and 2011, under-5 mortality fell from 166 to 88 deaths per 1000 live births. During the same period, infant mortality fell 42 percent, and is now comparable to wealthier countries in the region.

SOURCES: Ageze, 2012; Banteyerga et al., 2011; Central Statistical Agency [Ethiopia] and ICF International, 2012.

progress to a point of structural sclerosis. The Soviet health system developed in the 1920s and 1930s was appropriate to the disease burden and technology of the time. By the 1980s, it was already in decline (Atun and Coker, 2008; Fleck, 2013). Other countries in transition could soon face similar obstacles.

At the same time, changing the health systems and improving disease response can be mutually reinforcing. Before polio vaccination campaigns began in 1985, children in Mexico were only vaccinated at their mother’s request, and vaccine coverage was low, probably below 40 percent (Sepúlveda et al., 2006). The polio immunization program greatly increased coverage, but a 1990 survey found that only 42 percent of children were fully immunized on schedule (Sepúlveda et al., 2006). Poor infrastructure for patient tracking was preventing proper quality control (Knaul et al., 2012; Sepúlveda et al., 2006). The introduction of computerized immunization records in 1990 brought the percentage of children immunized on schedule up to 92 percent in only 3 years (Sepúlveda et al., 2006). The health effects were immediate: polio and diphtheria disappeared from Mexico within a year, autochthonous measles, within 6 years (Sepúlveda et al., 2006).

Similarly, donor funding for HIV helped strengthen parts of the health system in Ghana (Atun et al., 2011). Global Fund3 activities have improved the drug procurement system, and procurement for HIV supplies is now integrated with the national system; the Global Fund also supported health infrastructure improvements such as health post modernization, laboratory equipment, and vehicles for field supervision (Atun et al., 2011). Ghanaian health officials have credited these activities with creating an increased demand for health care (Atun et al., 2011).

Rwanda also used international grants for AIDS, tuberculosis, and malaria response to build stronger health systems (Binagwaho et al., 2014). During the last decade, health posts built for AIDS patients have been integrated with the primary care system; supply chains developed for distributing antiretrovirals have expanded to deliver medicines for a range of diseases (Binagwaho et al., 2014; Price et al., 2009). The benefits of these improvements have been felt disproportionately in the countryside, as the government made a deliberate decision to scale-up treatment in areas that would otherwise have been outside the reach of the health system (Binagwaho et al., 2014). After the 1994 genocide,

___________________________

3 Officially, the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria.

Rwandan leaders made rebuilding the health system a priority. As a result, health indicators improved; child mortality and mortality from tuberculosis, have both roughly converged with global averages (Binagwaho et al., 2014).

BOX 2-3

Improving Medicines Procurement and Distribution, Tamil Nadu, India

Until 1995, the South Indian state of Tamil Nadu required government health posts and hospitals to run independent medicines procurement and distribution systems, managing funding from one of the directorates: Medical Education, Medical and Rural Services, or Public Health and Preventive Medicine. Persistent allegations of corruption plagued the purchasers, none of which was large enough to command an efficient economy of scale; distribution costs were high and stock outs, common. In an effort to make drug procurement more efficient and transparent, the state government created the Tamil Nadu Medical Services Corporation, an autonomous agency responsible for every level of essential drug procurement and distribution to all government hospitals and health centers.

Medical Services Corporation chooses its drug suppliers through a transparent open-tender process. The details of each bid, including manufacturers’ licenses, quality standards, and prices, are visible to all prospective suppliers. Throughout the process, a system of checks and penalties helps keep quality consistent. Late deliveries face fines of 1.5 percent of the order’s cost; suppliers are not paid until after the delivery passes quality testing. Any supplier failing more than one quality test is blacklisted.

The corporation supplies drugs directly to district warehouses. Each facility then draws its stock from its respective warehouse, according to specific needs. Both warehouses and health facilities keep up-to-date records of their stock levels and drug use; the corporation monitors statewide drug levels and movement. If the data suggest a likely stock out, the corporation can transfer supplies from a neighboring district.

Medicines account for about 15 percent of the state health budget in Tamil Nadu, and are essential to clinical care. The Medical Services Corporation commands a purchasing power that has brought down the cost of certain classes of drugs, resulting in savings that have been used to furnish district hospitals with diagnostic equipment previously available only at expensive private hospitals. The corporation’s emphasis on openness, quality, and efficiency, has improved drug quality and patient confidence in the health system.

SOURCES: Lalitha, 2008; Muraleedharan et al., 2011.

Efficient Financing Improves Health Outcomes

Health insurance and other means of financial protection are gaining momentum as a way to improve health in developing countries. Universal health coverage is a movement to promote access to essential services without financial hardship. Universal coverage has considerable economic benefits that will be discussed in the next section. There is also growing evidence that it improves health, especially among the poorest people in society for whom the real and opportunity costs of care present obstacles.

Thailand and Mexico are both middle-income countries where universal coverage has been a goal since the early 2000s. In both countries, universal coverage increased use of health services among the poor, especially among those who had been paying for services out-of-pocket (Gruber et al., 2012; Knaul et al., 2012). Child mortality was one of the most improved indicators in both countries. In Thailand, infant mortality among the poorest 30 percent of the population fell 30 percent in only 2 years (Gruber et al., 2012). In Mexico, the first 6 years of universal coverage saw child mortality decline by 11 percent among the newly insured; for the rest of the country, the improvement was a more modest 5 percent (Knaul et al., 2012). Perhaps the most dramatically-changed health indicator after Mexico’s health reforms was the maternal mortality ratio, which dropped 32 percent among the previously uninsured and 3 percent among the rest of the country (Knaul et al., 2012).

A rapid improvement in maternal mortality ratio is a victory for the Mexican system. Ending preventable maternal deaths requires skilled attendants at every delivery and reliable emergency care; it is therefore notoriously slow to improve. Improvements in maternal health can therefore be seen as proxy measure of the strength of the health system. Ninety-nine percent of the world’s maternal deaths are in developing countries, “mak[ing] maternal mortality ratio the most inequitably distributed health indicator in the world” (Frenk et al., 2012, p. 2). Universal health coverage has the potential to correct this inequity. Health coverage schemes that start in rural areas and offer free treatment for the conditions poor people suffer from, can improve health with minimal increased expense. In Thailand, universal coverage cost slightly less than $25 per capita (Gruber et al., 2012). In Mexico, where the package of covered services has increased more, now covering more than 95 percent of outpatient and general hospital visits, the government

increased per capita spending on health by about $2324 between 2000 and 2010 (Knaul et al., 2012).

The exact costs of universal coverage will vary by country. The Lancet Commission on Investing in Health estimates that bringing an essential package of clinical interventions to 80 percent of the population in low- and middle-income countries by 2025 would be inexpensive; cost estimates range from less than $1 to $2.50 per person per year (Jamison et al., 2013). This investment could avert 37 percent of the global diabetes and cardiovascular disease burden and 6 percent of global cancer (Jamison et al., 2013; WHO, 2011). The cost of inaction, though harder to calculate, is almost certainly higher. Healthy people are more productive members of society; healthy children are better able to learn (Kieny and Evans, 2013). Failure to correct health inequalities can deplete human capital in developing countries, which are the most desperate to keep it, and undermine all efforts at development (Brearley et al., 2013).

Key Findings

- There is more than one correct way to organize a health system, but good systems are invariably grounded in political commitment, effective management and regulation, and the ability to adapt to limited resources.

- A judiciously directed increase in spending of less than $2.50 per person per year could avert a large share of the world’s cancer, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease.

Conclusion

- Narrow, disease specific programs best maintain their effectiveness when integrated with primary care.

___________________________

4 Adjusted for USD purchasing power parity.

Fostering Prosperity

A way to raise money for health and pool it fairly across the population is an essential piece of the health system (WHO, 2010a). Attention to health financing promises particular returns for the broader global development agenda. Every year, 100 million people fall into poverty because of health expenses, and millions more stay poor because they are too sick to work (Averill and Marriott, 2013; Xu et al., 2007). Improving the social safety net and bringing basic health care to these people will be an essential piece of ending global poverty and building a more prosperous world.

Health Expenses Are Poverty Traps

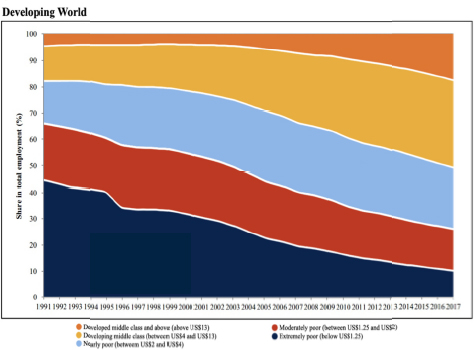

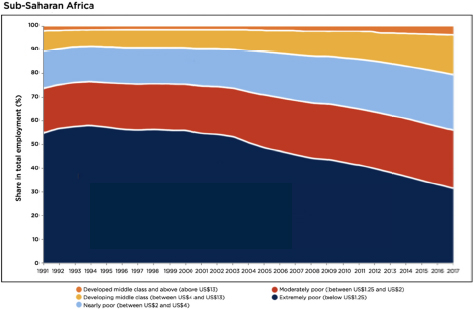

The path out of poverty is not linear. The $1.25-per-day poverty line is somewhat arbitrary,5 and many of the billion who crossed that line in past 20 years did so because they both started and remained close to the cutoff (Towards the end of poverty, 2013). While the middle class is growing in developing countries overall (see Figure 2-3), the relative prosperity of Latin America, Eastern Europe, and East Asia drives most of that success (Kapsos and Bourmpoula, 2013). The majority of sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia lives in some state of tenuous poverty. (See Figures 2-4 and 2-5.) The lines between extremely poor, moderately poor, and nearly poor are dynamic in these parts of the world. In rural India, Anirudh Krishna found that over 25 years, 11 percent of his sample had escaped poverty, while 8 percent who started out not poor had fallen below the poverty line, leading him to conclude that, “almost as many people have sunk into poverty over the past 25 years as have emerged from it” (Krishna, 2004, p. 131).

An illness or major accident is the main reason the poor in developing countries stay poor and the moderately less poor fall back (Krishna, 2004, 2011; Kristjanson et al., 2010). This problem often takes the form of “a succession of adverse events,” starting with an expensive illness or accident (Krishna, 2011, p. 5). To pay for health care, households invariably reduce basic consumption, and then they may sell their assets in distress or take on high-interest debt (Krishna, 2011; Kruk et al., 2009). The episode can go on for years, as with a chronic disease,

___________________________

5 Economists derive the cut point from the average poverty lines in the world’s 15 poorest countries, measured in 2005 dollars and adjusted for differences in purchasing power parity (Towards the end of poverty, 2013).

FIGURE 2-3 Emp oyment by economic class (2005 constant $, adjusted for purchasing power parity, per day), from 1991-2011, as a percentage of total employment in all low- and middle-income countries (2005 $, adjusted for purchasing power parity, per day).

SOURCE: Kapsos and Bourmpoula, 2013. Reprinted with permission from the International Labour Organization, Copyright 2013.

FIGURE 2-4 Employment by economic class (2005 constant $, adjusted for purchasing power parity, per day), in sub-Saharan Africa, 1991-2011, as a percentage of total employment.

SOURCE: Kapsos and Bourmpoula, 2013. Reprinted with permission from the International Labour Organization, Copyright 2013.

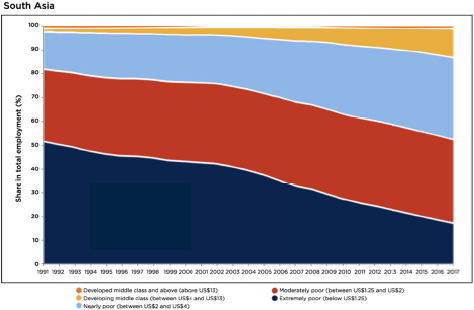

FIGURE 2-5 Employment by economic class (2005 constant $, adjusted for purchasing power parity, per day), in South Asia, 1991-2011, as a percentage of total employment.

SOURCE: Kapsos and Bourmpoula, 2013. Reprinted with permission from the International Labour Organization, Copyright 2013.

or end abruptly with unexpected funeral expenses. When the illness culminates in the death of the breadwinner, the household forfeits half or more of its long-term income (Krishna, 2011).

When patients have to pay a fee for health services, the fee can discourage use of preventative and curative medicine, but the effects of completely removing fees is not clear or consistent among countries (Lagarde, 2008; Waiswa, 2012). Removing the financial hardship of health expenses means reducing (or, for the poor, removing) the amount patients pay out-of-pocket, which accounts for about 70 percent of health spending in low-income countries (Kruk et al., 2009; Schieber et al., 2007; Xu et al., 2003). Requiring payment at the point of care can pose a catastrophic expense to the poorest patients (Xu et al., 2003).

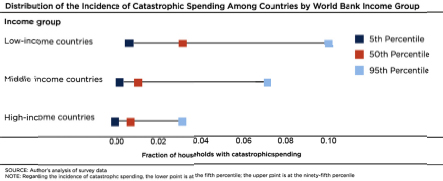

Health expenses are described as a financial catastrophe if they exceed 40 percent of a household’s income after basic subsistence needs are met (Xu et al., 2003). Using survey data from 89 counties covering almost 90 percent of the world, Xu and colleagues (2007) found that 150 million people per year face catastrophic spending for health. These 150 million people live all over the world, but are more likely to be found in low- and middle-income countries (see Figure 2-6).

Analyses of catastrophic health spending may underestimate the true hardship illness poses in poor countries, as they fail to account for the indirect costs associated with health care, things like transportation and

FIGURE 2-6 Distribution of the incidence of catastrophic spending among countries, by income group.

SOURCE: Copyrigh ed and published by Project HOPE/Health Affairs as Xu, et al., Protecting households from catastrophic health spending, Health Affairs (Millwood). 2007, 26(4):972-983. The published article is archived and available online at http://healthaffairs.org.

lost wages (Kruk et al., 2009). Research on hardship financing, either selling assets in distress or borrowing (often at high interest) to pay for health care, suggests that health expenses pose a financial hardship to about a quarter of all households in developing countries, nearly a third in sub-Saharan Africa and Southeast Asia (Kruk et al., 2009). The poorest households, which lack assets to sell, may raise funds by signing away their future earning power into debt bondage (Krishna, 2011). Debt bondage sabotages emerging economies. The International Labour Organization estimates that, after deductions for housing, uncompensated overtime, and labor below market wage, bonded labor costs the global economy $19.6 billion in unpaid wages, roughly $9 billion in the Asia Pacific region and $1.5 in sub-Saharan Africa (ILO, 2009).

Even when health expenditures are not catastrophic, they can hold back economic development. Households that can often save to prepare for emergency health expenditures (Dupas and Robinson, 2013; IPA, 2014). Their savings, while protective to the individual household, could have a detrimental effect on financial growth, as money saved is withheld from basic expenditures, the transactions that grow the economy. Protecting households from out-of-pocket health expenses can allow them to direct their cash to increased economic activity, thereby supporting their nation’s larger economic development (Frenk and de Ferranti, 2012).

Out-of-pocket health spending endangers patients, and prepayment (a system of collecting for health expenses before an illness) is one way to protect them (Xu et al., 2007). Prepayment comes from taxes, insurance, or both, and poses an obstacle for poor countries. Not only is it logistically complicated to collect revenues from people working in informal arrangements or at subsistence level, but many people are too poor to pay taxes at all (Xu et al., 2007). The most vulnerable people are also the least likely to buy insurance. Donors can help reduce their vulnerability by helping countries build effective prepayment systems. As the wealth in low- and middle-income countries increases, there are more potential revenue streams to draw from, but developing countries have little experience doing so effectively. Donor countries can provide valuable guidance on how to identify and collect taxes from sustainable sources.

Strong Systems Avoid Waste

Restructuring health systems in developing countries can make for more efficient and equitable use of health budgets. Health services in low- and middle-income countries often fail to reach people in rural and remote areas. There are organizational reasons for this. It is expensive, for example, to run teaching hospitals and tertiary care centers, so there are few of them, usually in cities, where they serve a relatively affluent, politically-aware patient base (IFC, 2007). Urban hospitals absorb a high proportion of national budgets, contributing to a problem of unfair distribution of spending. In Mauritania, for instance, 72 percent of public spending on hospitals benefits the richest 40 percent of the population (IFC, 2007). Hospital spending may be especially discriminatory against the poor, but the pattern holds across a range of services (Akazili et al., 2012). Research in sub-Saharan Africa indicates that although the disease burden in heaviest among the poorest groups in society, the distribution of services benefits the richest (Mills et al., 2012). In India, government data indicates that about 9 percent of all public health spending benefits the poorest fifth of the population, while the richest fifth take about 40 percent (Chakraborty et al., 2013).

Distance and cost pose barriers to the equitable delivery of health care, as does patient satisfaction with services (Mills et al., 2012). Nevertheless, people need health care; when the public system cannot meet their needs, patients go elsewhere. In Liberia, for example, a 14 year civil war decimated the health system. By 2008, most licensed formal providers worked in barebones clinics (Kruk et al., 2011). People in rural areas then sought care from traditional healers and medicine sellers three times more often than from formal clinicians (Kruk et al., 2011). In other cases, people rely on nongovernmental organizations for healthcare. Faith-based organizations in particular provide up to 40 percent of all health care in developing countries, including a large portion of HIV and AIDS home care (Kagawa et al., 2012; Woldehanna et al., 2005).

The private sector, a group that includes both for-profit and nonprofit providers, accounts for the majority of health services among the poor in developing countries (Berendes et al., 2011; Das et al., 2012). In Ethiopia, Kenya, Nigeria, and Uganda, more than 40 percent of the poorest fifth of society get health care from private, for-profit providers (IFC, 2007). Competition from the private sector could help improve the quality and efficiency of public health services, but it is difficult to create

market competition in health without extensive regulatory and enforcement capacity (Yip et al., 2012). As the relative importance of for-profit providers grows in developing countries, it will be important to build government capacity for oversight and regulation. Otherwise, there will be increased risk of waste and more money to be wasted as spending on health increases.

The WHO estimates that inefficiency causes the wasting of 20-40 percent of all health spending (WHO, 2010b). The key to reducing this waste lies in strengthening the basic building blocks of health systems. Table 2-1 shows the 10 leading sources of inefficiency in health and offers ways to improve them. Notably, all the main causes of waste are in failures of the health system.

Efficient Health Spending Improves Productivity

Making the most of financial contributions to the health system is one of the main challenges facing governments today. The potential payoffs for increasing efficiency are substantial. As described earlier, recent economic models indicate that a judiciously directed increase of $5 per person per year in the 74 countries that account for 95 percent of maternal and child deaths would yield a return of nine times that investment in terms of lives saved, disability averted, unplanned pregnancies avoided, greater workforce participation, increased savings and investment (Stenberg et al., 2014). A 2 percent increase in health spending could underwrite the additional $5 per person per year needed to realize tremendous societal gains (Engström et al., 2013; Stenberg et al., 2014). The cost of failure to act, in contrast, is steep. Maternal deaths alone take $15 billion per year from the global economy, acting through both the loss of a healthy adult and the vastly decreased prospects of her children (USAID, 2001).

Historical case studies suggest that improved health and nutrition accounted for about one-quarter of the GDP increase in Britain over from 1780-1979 (Fogel, 1997; Jamison et al., 2013). In the twentieth century, the effects appear to come more quickly. In an analysis of 53 countries’ data, Jamison and colleagues (2005) estimated that health improvements between 1965 and 1990 accounted for about 11 percent of national economic growth. In either case, the full returns on investments in health become evident with a long time horizon (Belli et al., 2005).

TABLE 2-1 Sources of Health System Waste

| Source of inefficiency | Common reasons for inefficiency | Ways to address inefficiency | Health system building block |

|

1. Medicines: underuse of generics and higher than necessary prices for medicines |

Inadequate controls on supply-chain agents, prescribers and dispensers; lower perceived efficacy/safety of generic medicines; historical prescribing patterns and inefficient procurement/distribution systems; taxes and duties on medicines; excessive markups | Improve prescribing guidance, information, training, and practice. Require, permit or offer incentives for generic substitution. Develop active purchasing based on assessment of costs and benefits of alternatives. Ensure transparency in purchasing and tenders. Remove taxes and duties. Control excessive mark-ups. Monitor and publicize medicine proves. |

|

|

2. Medicines: use of substandard and counterfeit medicines |

Inadequate pharmaceutical regulatory structures/mechanisms; weak procurement systems | Strengthen enforcement of quality standards in the manufacture of medicines; carry out product testing; enhance procurement systems with pre-qualification of suppliers |

|

|

3. Medicines: inappropriate and ineffective use |

Inappropriate prescriber incentives and unethical promotion practices; consumer demand/expectations; limited knowledge about therapeutic effects; inadequate regulatory framework | Separate prescribing and dispensing functions; regulate promotional activities; improve prescribing guidance, information, training and practice; disseminate public information |

|

|

4. Health care products and services: overuse or supply of equipment, investigations, and procedures |

Supplier-induced demand; fee-for-service payment mechanisms; fear of litigation (defensive medicine) | Reform incentive payment structures (e.g. capitation or diagnosis-related group); develop and implement clinical guidance |

|

|

5. Health workers: inappropriate or costly staff mix, unmotivated workers |

Conformity with predetermined human resource policies and procedures; resistance by medical profession; fixed/inflexible contracts; inadequate salaries recruitment based on favoritism | Undertake needs-based assessment and training; revise remuneration policies; introduce flexible contracts and/or performance-related pay; implement task-shifting and other ways of matching skills to needs |

|

|

6. Health care services: inappropriate hospital admissions and length of stay |

Lack of alternative care arrangements; insufficient incentives to discharge; limited knowledge of best practice | Provide alternative care (e.g., day care); alter incentives to hospital providers; raise knowledge about efficient admission practice |

|

|

7. Health care services |

Inappropriate level of managerial resources for coordination and control; too many hospitals and inpatient beds in some areas, not enough in others. Often this reflects a lack of planning for health service infrastructure development. | Incorporate inputs and output estimation into hospital planning; match managerial capacity to size; reduce excess capacity to raise occupancy rate to 80-90% (while controlling length of stay) |

|

|

8. Health care services: medical errors and suboptimal quality of care |

Unclear resource guidance; lack of clinical care standards and protocols; lack of guidelines; inadequate supervision | Improve hygiene standards in hospitals; provide more continuity of care; undertake more clinical audits; monitor hospital performance |

|

|

9. Health system leakages: waster, corruption, and fraud |

Unclear resource allocation guidance; lack of transparency; poor accountability and governance mechanisms; low salaries | Improve regulation/governance, including strong sanction mechanisms; assess transparency/vulnerability to corruption; undertake public spending tracking surveys; promote codes of conduct |

|

|

10. Health interventions: inefficient mix and inappropriate level of strategies |

Funding high-cost, low-effect interventions when low-cost, high-impact options are unfunded. Inappropriate balance between levels of care, and/or between prevention, promotion and treatment | Regular evaluation and incorporation into policy of evidence on the costs and impact of interventions, technologies, medicines, and policy options |

|

SOURCES: Chisholm and Evans, 2010; WHO, 2010b. Adapted with the permission of the publisher, from “More health for the money” in the World Health Report: Health systems financing: The path to universal coverage. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2010 (Table 4.1, p. 63, http://www.who.int/whr/2010/10_chap04_en.pdf?ua=1, accessed June 3, 2014).

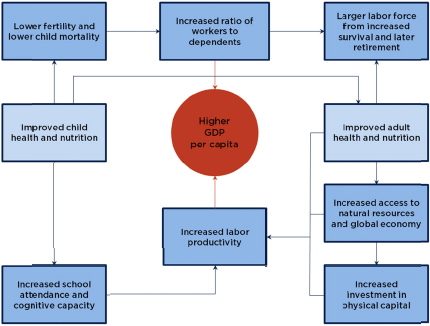

Figure 2-7 shows the main channels through which health improves per-person income. As child survival and family planning improve, couples can choose to have fewer children. Working adults are therefore responsible for fewer dependents, meaning that workers make up a greater share of the national population. As life expectancies rise, there are more healthy adults contributing to workforce for more time, earning, saving, and investing for longer. Healthy workers are more productive; healthy children are better students. In time, the country becomes more attractive for foreign direct investment (Jamison et al., 2013).

There is also an inherent value of health and a worth simply to extending healthy years of life (Jamison et al., 2013). In analyses that account for both the increase in income and the value of added life years caused by improved health, the benefits of reducing infections and improving maternal and ch ld health exceed the costs by a factor of 9 to 20 (Jamison et al., 2013).

FIGURE 2-7 Pathways by which health improves GDP per person.

SOURCE: Jamison et al., 2013, adapted with permission from TheWorld Health Report 1999: Making a Diff rence, Geneva: World Health Organization, 1999 (Figure 1.5, p. 11, http://www.who.int/whr/1999/en, accessed August 28, 2014). Reprinted with permission from the World Health Organization.

Investing in health reduces poverty and is sound economic policy for all governments (Engström et al., 2013). American companies increasingly see their future in the emerging markets of Africa, Asia, and Latin America. Improving the productivity and lifetime earning potential of workers and consumers in these markets will have far-reaching reverberations, improving prosperity abroad and in the United States.

Key Findings

- The middle class is growing in developing countries overall, but prosperity in Latin America, East Asia, and Eastern Europe accounts for most of that growth. In sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia, almost as many people have fallen into poverty over the past 20 years as have escaped it.

- The poor stay poor and the less poor fall back because of health expenses. For one-third of all households in sub-Saharan Africa and Southeast Asia health expenses pose a financial hardship.

- Households respond to hardship by selling assets in distress, taking on high-interest debt, or forfeiting their future earnings through debt bondage. All these practices sabotage emerging economies.

- Charging patients at the point of care prevents the poorest people from seeking care, or at best, encourages them to delay treatment until the condition worsens.

Conclusions

- Governments can prevent people from falling into poverty by improving health financing, and building capacity for oversight and regulation.

- Efficient spending on health improves global productivity and is sound economic policy for all countries.

Advancing Global Security

The return on investment in health systems goes beyond economic gains. A strong health system allows for prompt and effective response to pandemic disease, natural and man-made disasters. When this response falters, there is an immediate health threat as well as a longer-term risk to political stability.

One of the biggest pandemic threats to emerge in recent years is Ebola virus disease (called simply Ebola), emerging in West Africa in the spring of 2014 (CDC, 2014c; WHO, 2014a). A disease of uncommon virulence and high case-fatality, Ebola would tax any health system, but the West African countries affected have particular vulnerabilities (Ebola

virus: Liberia health system “overtaxed,” 2014; Gostin et al., 2014; WHO, 2014a). As of August 28, 2014, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) records indicate 1,552 suspected deaths and 3,069 suspected and confirmed cases in Guinea, Liberia, Nigeria, and Sierra Leone (CDC, 2014a).

The clinical presentation of Ebola is similar to many other endemic tropical diseases. Confirming cases, the first step to effectively quarantining and treating them, requires a laboratory testing system (Green, 2014). Ebola patients require inpatient treatment, stressing limited hospital infrastructure; five of the largest hospitals in the Liberian capital closed in response to the epidemic (Ebola virus: Liberia health system “overtaxed,” 2014; WHO, 2014a). The countries affected are now in a state of emergency response, with new control measures curtailing social gatherings (Gostin et al., 2014; Nossiter, 2014). The burden of controlling pandemic spread, combined with the risks of treating patients, led Sierra Leone President Ernest Bai Koroma to conclude, “the very essence of our nation is at stake” (Nossiter, 2014).

The Ebola crisis has drawn attention to the consequences of neglecting health systems development in developing countries. Only 20 percent of the world’s nations are prepared for pandemic response (Kerry et al., 2014). The tools that would enable this response—a well-trained workforce, an information system to support surveillance and data sharing, a solid infrastructure for clinical care and laboratory analysis, and strong management of the health sector—are essential pieces of the health system. For this reason, the Department of Health and Human Services’ Global Health Strategy gives as one of its main objectives the comprehensive strengthening of health systems (HHS, 2011). Building the health system in developing countries will protect people around the world from pandemic threats and contribute to more politically stable societies.

Health Infrastructure Supports Emergency Response

Concern with developing countries’ public health systems has grown over the past 10 years, partly because of the threat of emerging pandemic diseases such as Ebola. In 2004, David Heymann and Guénaël Rodier observed that the SARS epidemic “made one lesson clear early in its course: inadequate surveillance and response capacity in a single country can endanger … the entire world” (Heymann and Rodier, 2004, p. 173).

Sometimes society controls this danger. During the SARS outbreak, international collaboration helped contain the disease within a few weeks (Grady and Altman, 2003). In only 4 months, all transmission was interrupted in 27 countries (Heymann and Rodier, 2004). Other times, meaningful collaboration is lacking and response suffers. Two years have passed and at least 2096 people have died since the Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus emerged, but the source of the virus is still unclear (PLOS Currents and PLOS Pathogens, 2014; McNabb et al., 2014; WHO, 2014e). There is similar doubt about Ebola’s natural reservoir (CDC, 2014b). In any case, pandemic diseases disrupt people’s lives and take a toll on the global economy long after the acute emergency response phase. SARS halted travel and hurt business in China and Southeast Asia, costing the region $50 billion (UN System Task Team, 2012). The World Bank estimates that Ebola will cost Guinea, an impoverished country hard hit by the epidemic, a full percentage point of annual economic growth (World Bank, 2014).

Building a system for international cooperation during an outbreak is the goal of the International Health Regulations, a set of legally binding rules on the surveillance and response to outbreaks of potential international public health consequence (WHO). The regulations are built around the premise that containing a disease while it is still local is the best way to prevent a global epidemic (Rodier et al., 2007). To comply with the regulations, countries need to develop the basic health infrastructure to detect and report potential threats and respond to national emergencies (Rodier et al., 2007).

Although 196 countries have adopted the International Health Regulations, only about 20 percent of those countries had fully implemented them by 2013 (Fischer and Katz, 2013; WHO). Implementing the regulations requires strength in eight basic capacities (Katz et al., 2012). As Table 2-2 indicates, these eight strengths are essentially components of the health system. It will be impossible to implement the International Health Regulations without improving the health system foundation they draw on.

Investments in the health system (such as laboratories, health information systems, communication, and human resource management) that improve daily functioning also strengthen the system’s ability to respond to threats (Kruk, 2008a). The ability to respond to all diseases, even those that are not likely to become global threats, builds the same

___________________________

6 As of June 11, 2014.

TABLE 2-2 The International Health Regulations Build on a Functional Health System

| International Health Regulations’ Core Capacities | Building Block of the Health System |

| Legislation to support and funding to implement the procedures |

|

| Leadership to coordinate a national emergency response |

|

| Early detection of public health events through routine surveillance and situational awareness of potential hazards |

|

| Outbreak response, including case management, infection prevention and control |

|

| Preparedness of a national emergency plan |

|

| Procedures for risk communication |

|

| Human resources to implement the regulations |

|

| Laboratory and diagnostic tools, the means to collect and transport specimens, laboratory surveillance Surveillance and response at points of entry |

|

SOURCES: Katz et al., 2012; WHO.

technical depth required for emergency management (Frieden et al., 2014). Such was the logic behind the Global Health Security Agenda, a U.S. government program working in 30 partner countries to develop the capacity for outbreak response (HHS). One of the program’s main targets for its partner countries over the next 5 years is to reach 90 percent of all one-year-olds with measles vaccine (HHS). This target recognizes that the groundwork necessary to prevent measles is the same as what would be needed for response to any epidemic threat (Frieden et al., 2014). Similarly, Box 2-4 describes how epidemic response in Uganda improved as part of the Global Health Security program.

Developed health systems have an emergency response capacity built into their operations. Such response capacity was evident after the Boston Marathon bombings. The city health system could absorb the shock of acute disaster response; “not a single patient who made it to a hospital died” (Farmer, 2013). Natural disasters and acts of violence are only more common in poor countries, so the need for resilience is even

BOX 2-4

Building Epidemic Response in Uganda

Targeted investments in health infrastructure can improve emergency response relatively quickly. As part of the Global Health Security effort, the Uganda Ministry of Health and the CDC demonstrated how changes in laboratory management, informatics, and logistics could improve outbreak response. The Ugandan ministry selected three pathogens (MDR-TB, cholera, and Ebola) that pose serious risk to their population, and 17 pilot districts where there is both a history of cholera and, because of PEPFAR, some infrastructure for specimen transport and tuberculosis detection. Over six months, the program provided targeted training for laboratory staff, district surveillance officers, and coordinating logisticians. The collaborators developed protocols for packaging and shipping specimens safely on motorbikes and through the Ugandan post office. They stocked diagnostic kits at local hospitals, and developed a way to report suspected outbreaks using text messaging. They also updated the ministry’s online database to allow field workers to immediately notify Kampala of a suspected case. After 6 months, 14 of the 16 pilot laboratories had improved their systems for recognizing outbreaks, communicating to the ministry, and transporting specimens.

The Ugandan government led the epidemic response pilot, a fact to which the CDC technical collaborators attribute much of its success. The program built on existing national informatics and surveillance systems. The system has been in regular use since the pilot program ended, leading to confirmation of cases of West Nile virus, Zika virus, Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever, hepatitis E, and MDR-tuberculosis. The ministry also used the new emergency response system twice in 2013: once a preventative measure at a large cultural event, and once to screen pilgrims returning from the Hajj for Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus.

SOURCE: Borchert et al., 2014

greater. When the health systems cannot respond to humanitarian emergencies, there is a risk of an acute problem growing into a protracted political crisis. Investments in health (such as laboratories, information systems, communication systems, and human resource management) improve general functioning and the system’s ability to respond to threats.

Unsustainable Health Systems Are a Political Risk

Financial sustainability in health means “having enough reliable funding to maintain current health services for a growing population and to cover the costs of raising quality and expanding availability to acceptable levels. Usually the financial sustainability goal also means achieving these funding levels with a country’s own resources” (Leighton, 1995, p. 2). Determining what constitutes an acceptable level of coverage is up to the leaders running a country’s health sector. Miscalculations in sustainable cost or coverage can have far-reaching political repercussions.

Political stability allows health systems to function. There is no doubt that prolonged conflict destroys health infrastructure, decimates the health workforce, and causes governments to decrease health expenditures (Waters et al., 2007). It is also true that neglect of the health system can undermine the stability of governments. People need health services. As the middle class grows, demand for health care increases; failure to respond to this demand spurs unrest.