The health of women and children in poor countries has improved dramatically over the past 25 years. Child mortality has fallen by almost half since 1990 (You et al., 2013). Maternal deaths have declined by about the same amount (WHO, 2012c). Now there is good consensus that a package of life-saving services could vastly reduce child and maternal deaths in developing countries (Bhutta et al., 2005; Bryce et al., 2006; Jones et al., 2003; Stenberg et al., 2014; USAID Bureau for Global Health, 2013). Demographic models indicate that the widespread, equitable implementation of these simple interventions could eliminate preventable maternal and child deaths over the next 20 years (Jamison et al., 2013). For the first time in history, ending the world’s preventable maternal and child deaths is a realistic goal.

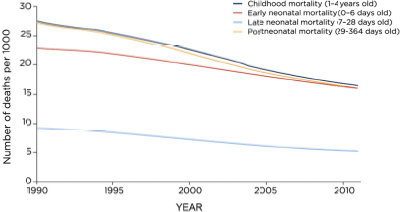

Meeting this goal still presents challenges, however. Only 31 of 137 developing countries will meet Millennium Development Goal 4, dramatically reducing child mortality by 2015; far fewer will reduce maternal deaths to levels set in Millennium Development Goal 51 (Lozano et al., 2011). UN models indicate that the global child mortality rate will fall to the specified level around 2028 (UN, 2014). But, if current trends continue (see Figure 1-1), many countries will not meet the 2015 targets until 2040 or later (Lozano et al., 2011). This is not to say that countries must necessarily stay on their current trajectories—rapid change is possible. Improvements in health rarely take a linear path (Frøen and Temmerman, 2013; Walker et al., 2013). In maternal and

___________________________

1 The Millennium Development Goals are a set of global targets to improve health and standard of living in poor countries. They were developed at the UN Millennium Summit with the support of 189 countries (Oestergaard et al., 2013; Oxfam International, 2011). Millennium Development Goal 4 is to reduce child mortality by two-thirds of 1990 rates; Goal 5 includes a target for three-quarters reduction in maternal mortality ratio from 1990 levels (UNICEF, 2012).

FIGURE 1-1 Worldwide early neonatal, late neonatal, post neonatal, and childhood mortality rates, 1990-2011.

SOURCE: Reprinted from The Lancet, Vol. 378, Lozano, et al., Progress towards Millennium Development Goals 4 and 5 on maternal and child mortality: An updated systematic analysis, pp. 1139-1165, Copyright 2011, with permission from Elsevier.

child health especially, progress for the poorest people in society will have disproportionate returns as the poor tend to have more children and a higher burden of disease (Victora et al., 2012). Continuing success in global health over the next 25 years will not, however, be possible using the methods of the 1990s and 2000s. In much of the world, the easy gains have already been made. The challenge for the future of global health is to deliver good services efficiently to an ever larger number of people.

Only a fraction of those who need lifesaving health services receive them (Victora et al., 2004). Even among those who get treatment, the effects can be variable. A study of maternal care in relatively large, functional, district health posts2 in Africa, Asia, Latin America, and the Middle East found far higher maternal mortality than would be expected in what were mostly secondary and tertiary care hospitals. This failure was not due to neglect of the appropriate interventions, most of which were used nearly 90 percent of the time. Nor was it obscured by small numbers; the risk grew progressively worse—two to three times worse—

___________________________

2 Defined as those seeing at least 1,000 deliveries per year and having the capacity to perform a caesarean section.

in parts of the world with the highest likelihood of death in childbirth (Souza et al., 2013). Rather, these deaths are the result of a dozen smaller failures: delays in treatment, lack of proper referrals, clinicians not trained in emergency case management, poor quality medicines, problems with blood banking, and stock outs of essential supplies. Making progress against maternal mortality requires addressing a constellation of related problems.

The same is true for deaths in children under five. Around the world, deaths in the first month of life, often on the first day, account for the greatest portion of child mortality (Liu et al., 2012). Newborn lives are protected with many of the same interventions in pregnancy and delivery that benefit their mothers. Other common killers of children, including pneumonia, diarrhea, and malaria, are greatly complicated by the potentiating effects of poor nutrition (Black et al., 2008; You et al., 2013). Although the relative burden of different infections varies by country, there is a resoundingly common problem with equity. Poor children are more likely to get sick; they are more exposed to disease vectors, contaminated water, poor housing, and crowding. Their poor nutrition and lowered immunity make ordinary infections more dangerous for them, but they are less likely to access any lifesaving measures, from routine immunizations to curative care (Gwatkin et al., 2004; Victora et al., 2003). Improving child survival means removing the barriers that keep the most vulnerable people from health (UNICEF, 2010).

Yet there is a risk to putting maternal and child health too much at the center of a global health agenda. Such emphasis, though helpful in building momentum for change and marshaling funding, can make pregnancy, delivery, and early childhood services a sort of vertical health program,3 delivering good care selectively to a narrow group. The very importance of these services makes it necessary to deliver them as effectively as possible, integrating them with primary care. Women of childbearing age in poor countries have a range of health complaints, including noncommunicable conditions such as diabetes, hypertension, cancer, asthma, depression, and injury (Stenberg et al., 2014). Children, similarly, should not survive the routine infections of early childhood only to suffer at school age for want of basic surgery or trauma care. Indeed, recent analyses indicate that the world’s overall burden of death from infections, malnutrition, maternal and neonatal causes, is decreasing; it fell by 9.2 percentage points between 1990 and 2010

___________________________

3 A health program targeted to a specific condition, often with specialized management, logistics, and delivery.

(Lozano et al., 2012). At the same time, the share of deaths from cancer, injury, diabetes and heart disease has grown. Non-communicable causes now account for two-thirds of all deaths worldwide (Lozano et al., 2012).

EMERGING MOMENTUM FOR UNIVERSAL HEALTH COVERAGE

Balancing competing priorities in health is at center of an important discussion on how to plan for global development after 2015 (sometimes called the post-2015 development agenda). There is an emerging consensus, backed by the World Bank and the World Health Organization (WHO), that bringing health and economic stability to the most vulnerable people in the world can be best achieved though universal health coverage (Brearley et al., 2013; Latko et al., 2011). The goal of universal coverage is “to ensure that all people obtain the health services they need without suffering financial hardship when paying for them” (WHO, 2012b). As such, it is a means to an end, a way to bring the full benefits of a healthy life to everyone.

Universal health coverage aims to bring about a fairer distribution of essential health services. This is partly to correct a historical problem, whereby public spending in developing countries has favored the rich (Moreno-Serra and Smith, 2012). In countries that have implemented universal coverage, the removal of financial barriers to care and the investment in primary health services have been an effective remedy to this problem. In Thailand, for example, the benefits of universal coverage, especially the reduction in infant mortality, were more pronounced among the poor (Gruber et al., 2012; Vapattanawong et al., 2007).

That does not mean that the growing support for universal coverage is a promise to supply high-tech curative procedures to every patient. Universal coverage applies to priority conditions, conditions which are, ideally, identified from national epidemiological data (Bristol, 2014; WHO, 2012b). Furthermore, reaching universal coverage in a country can be long process—it took 127 years in Germany (Averill and Marriott, 2013). There is no reason, however, that developing countries should have to wait as long. Thailand has made rapid progress over the past 40 years, introducing a national coverage scheme in steps, starting with the people in formal employment and with basic coverage for the poor, and gradually expanding from there (Hanvoravongchai, 2013).

Women and children have the most to gain from universal coverage; they are the furthest behind (Quick et al., 2014). Because they are

poorest, they are also the most deterred by costs. But they are not the only ones who stand to benefit. Building a cohesive health system in low- and middle-income countries, which universal coverage aims to do, is a necessary pre-requisite for all of the Millennium Development Goals in health (Travis et al., 2004). In a larger sense, building a reliable health infrastructure in developing countries has consequences that go beyond health, to advancing global prosperity and security. When implemented effectively, universal coverage can be an instrument for poverty reduction and government accountability as well as health. Such are the concerns of the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), the agency in the U.S. federal government, “that works to end extreme global poverty and enable resilient, democratic societies to realize their potential” (USAID, 2014).

THE CHARGE TO THE COMMITTEE

USAID’s Bureau for Global Health commissioned this report to study the value of health system strengthening in low- and middle-income countries. This discussion is particularly important now, as the timeline on the Millennium Development Goals runs out and new goals for global development replace them. The U.S. government can use this time to take stock of its investment in global health, reviewing its changing role as a partner in development. To this end, USAID commissioned the Institute of Medicine (IOM) to bring together an expert committee to produce a short and focused report on investing in health systems in developing countries. Box 1-1 gives background on the study and statement of task.

This report aims to help government decision makers assess the rapidly changing social and economic situation in developing countries and its implications for effective development assistance. Many countries that have traditionally been recipients of donor assistance for health are now able to finance basic health services from domestic monies (Jamison et al., 2013). Even among countries that depend more on donor aid, the burden of disease and health needs is changing; donor strategy has to change with it. In light of these developments, this report will discuss why an investment in health systems is crucial to sustain the gains of the past 25 years. First, it will describe why it is in the United States’ pressing national interest to improve health systems in developing countries and why that needs to be done now. Next, it will lay out what actions will best serve this goal and how to go about them.

BOX 1-1

Statement of Task and Committee Process

This report was commissioned by the USAID Office in Health Systems, a division of the Bureau for Global Health, after consultation with the IOM Standing Committee to Support USAID’s Engagement in Health Systems Strengthening in Response to the Economic Transition of Health. At their meeting in February 2014 the Standing Committee helped to develop the statement of task shown below. While doing this, the Standing Committee was sensitive to the fact that this report would be a narrowly focused project, and that its authoring committee would meet only once.

The Institute of Medicine convened an 11-person ad hoc consensus committee in March 2014 to examine the questions set out in the statement of task. These ad hoc committee members included some members of the Standing Committee and other experts with needed expertise. (See Appendix A for committee member biographies.) The committee met in April 2014 to hear testimony and deliberate. (See Appendix B for the meeting agenda.) The committee developed an approach to their task, considered the evidence and testimony, and came to tentative conclusions at this meeting. At this time, they determined that questions relating to corruption in donor aid, and the role of donor and recipient governments in controlling corruption, were outside the scope of this report.

Over the next months, the committee revised drafts, refined conclusions, and solidified references, resulting in the present report.

Statement of Task

An ad hoc committee under the auspices of the Institute of Medicine will prepare, over 6 months, a brief and focused report to Congress and other U.S. government authorities on the value of American investment in health systems in low- and middle-income countries. The report will summarize how health systems improvements can lead to better health, reduce poverty, and make donor investments in health sustainable. The committee should also describe an effective strategy for donor investment in health given the increasing self-sufficiency in USAID’s partner countries. The study will not involve detailed technical comparisons of specific regional or country strategies, but rather will recommend broad priorities for health systems strengthening.

Key Finding

- The health of women and children in poor countries has greatly improved over the past 25 years, but continued progress will not be possible without a better system to bring health services to the periphery of society.

Conclusions

- Improving maternal and child survival is an important goal, but there is a risk to making it the centerpiece of the global health agenda. The global disease burden is changing. Countries need a way to respond to these changes, and creating a targeted health program for maternal and child health is not a viable long-term solution.

- Bringing good services to a large number people is the next main challenge in global health.

- Developing a strong health infrastructure in low- and middle-income countries will improve health, and will have consequences that go beyond health to building a more stable and prosperous world.