Creating the Conditions for Sustainability

KEY SPEAKER POINTS

- The first step in blending knowledge into the flow of work, Brent James said, is to identify a high-priority clinical process—one for which research will have a relatively rapid impact on care delivery performance as measured in patient, clinical, and cost outcomes—and build an evidence-based best practice protocol which will admittedly be imperfect but that creates a low-energy state in which the best practice is the default choice that happens automatically unless modified intentionally by the physician.

- Thomas Garthwaite said that the best physicians for his organization are the ones who embrace a dialogue around clinical excellence and that engaging all members of the health care team as active research participants improves retention and boosts morale.

- Being an organization known for research aimed at improving care can help grow market share, Garthwaite said.

- A critical piece of a sustainable research enterprise, Garthwaite added, is the ability to estimate impact, which not only provides feedback to physicians but also offers justification to management.

- What patients want from research, Sally Okun said, is to believe that the health care professionals who participate in research are going to bring the knowledge that they gain from that research to bear on their care. What patients will not tolerate, she added, is being asked to participate in research that does not eventually benefit them or future patients.

- One model of sustainability has a value proposition of what can be called reasonable value at acceptable cost, Lewis Sandy said, while another creates an environment in which research activities pay for themselves through continuous learning and improvement and are positive contributors to a return on investment.

This session, moderated by Lewis Sandy, executive vice president for clinical advancement at UnitedHealth Group, explored the business and financial issues and opportunities presented to organizations by moving toward continuous learning and improvement. Sandy said that there are at least three changes in the context in which health care exists today that could contribute to sustainability: payment reform and the alignment of incentives, the changing role of the consumer, and transparency.

Brent James, executive director of the Institute for Health Care Delivery Research and vice president of medical research and continuing education at Intermountain Healthcare, started the session with a presentation on how to create the conditions for sustainability. Three respondents—Thomas Garthwaite, chief operating officer and vice president of the HCA Clinical Services Group; Sally Okun, vice president for advocacy, policy, and patient safety at PatientsLikeMe; and Karen DeSalvo, National Coordinator for Health Information Technology—then provided their insights on the issue of sustainability. An open discussion followed the panel’s presentations and comments.

THE LEARNING HEALTH CARE SYSTEM

Before discussing the topic at hand, Brent James recommended a text called Realistic Evaluation that proposes an alternative to the randomized clinical trial that may be useful for evaluating context-specific interventions (Pawson and Tilley, 1997). He also recommended a second text, Meta-Analysis by the Confidence Profile Method, that also describes methods that could be used to construct more appropriate designs for testing the complex interventions that this workshop is discussing (Eddy and Shachter, 1992).

In 1991 James and his colleagues conducted a large randomized clinical

trial designed to assess the comparative effectiveness of using an “artificial lung” versus standard ventilator management for acute respiratory distress syndrome. They discovered that there was huge variation in the control arm of the trial with regard to the ventilator settings used by expert pulmonologists, something that had never been noticed or studied. As a result, the researchers created a protocol for ventilator settings in the control arm of the trial. James mentioned this study to illustrate the point that Level 1, 2, or 3 evidence on best practices is available only about 15 to 25 percent of the time, depending on the specific condition, and that percentage can range from close to zero to up to half of the time (see Figure 5-1).

James also noted that the rate of production of new knowledge exceeds the capacity of the unaided expert mind to assimilate all of that knowledge, creating a major source of variation in practice. In 2009, for example, the results from just under 30,000 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) were published in the medical literature, with the results of 75 trials and 11 systematic reviews appearing in the literature every day. As a result, expert consensus is often unreliable. In addition, guidelines rarely if ever guide practice, and even though physicians say they are useful and that guidelines change their practice, they in fact do not change practice, perhaps because no guideline, with rare exception, perfectly fits any individual patient.

An important question that health care faces is how to blend knowledge into the flow of work so that access to knowledge at the point of care does not rely solely on human memory. James said the first step is to identify a high-priority clinical process and build an evidence-based best practice protocol, which will admittedly be imperfect. Intermountain Healthcare then uses what James characterized as 20 different tools for blending that

FIGURE 5-1 Five levels of clinical research at Intermountain Healthcare.

SOURCE: Reprinted with permission from Brent James.

protocol into the clinical workflow. What this does, he explained, is create a low-energy state in which the best practice is the default choice that happens automatically unless modified intentionally by the physician. The 20 tools include standing orders, clinical flow sheets, patient work sheets, and other action lists. Together, these tools turn evidence-based best care into routine care.

One of these tools is an embedded data system that tracks protocol variations and both short-term and long-term patient results. A critical constraint here is that Intermountain Healthcare demands that clinicians vary the treatment protocol on the basis of each patient’s individual needs. The resulting data are used to create a feedback loop that constantly updates and improves the protocol, a process that is transparent to frontline clinicians. These cycles of data collection and analysis also generate the formal knowledge that will go into peer-reviewed publications. Applying this type of learning trial design to acute respiratory distress syndrome patients led to a change in protocol that increased survival from 9.5 percent to 44 percent with a reduction in costs of approximately 25 percent and an increase in physician productivity of almost 50 percent. “This was the first time since this syndrome was defined in the 1960s that anybody had shown an improvement in clinical outcomes,” James said. He added that Intermountain Healthcare has used this process with more than 100 different clinical practices to produce dramatically better clinical outcomes and, in most cases, at dramatically lower cost.

There are several lessons from these experiences, James said. First, this knowledge management system saves lives, which is the real measure of success. Second, James observed that in his experience better care is almost always less expensive, and he estimated that the Intermountain system saves $350 million per year thanks to these improvements, a dramatic return on investment.

Because of these outcomes, Intermountain Healthcare has used this knowledge system as a foundation that has enabled it to make clinical quality its core business strategy, James explained. Beginning in 1996, Intermountain conducted a key process analysis of more than 1,400 clinical processes, with each process being a way that a patient experiences care. Of these, 104 processes—42 outpatient and 62 inpatient—were identified as accounting for about 95 percent of all care the system delivered. By 2000 Intermountain had a full rollout of this knowledge system and full administrative integration. One problem that occurred was that, despite having a fully integrated and widely used EHR and full activity-based costing, there were still large pieces of data missing that were essential for clinical management. In fact, these missing data were the reason that Intermountain’s first two initiatives for clinical management failed. The remedy was to deploy a methodology for identifying critical data elements for clinical

management and then to build those into clinical workflows, James said. Intermountain also created 58 clinical development teams, each led by a physician who has time allotted for this role, and it hired 17 statisticians to work with these teams.

The clinical processes tracked by these teams account for approximately 80 percent of all care delivered within the Intermountain system. Every patient is followed longitudinally, and the record is stored in a condition-specific patient registry. James noted that the system currently has about two petabytes of data that are used in routine clinical management. All told, these activities and the data storage component cost about $7 million annually, and they enable James and his team to validate every published result in the context of the Intermountain system. “My job,” James said, “is to make sure that my physicians and nurses can say to a patient that, in our hands, ‘This is what you will get if we pursue this particular clinical course.’”

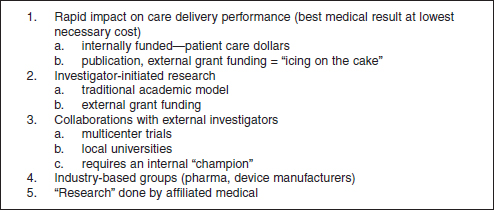

Another step that Intermountain has taken is to divide its clinical research effort into five levels.

Level 1 research has a relatively rapid impact on care delivery performance as measured in patient, clinical, and cost outcomes. “This is the only area where I can justify spending Intermountain patient care dollars,” James said. Priorities for Level 1 research are set by Intermountain’s clinical development teams, and no external funding is required, James said, although he added that once this type of data-driven research effort is established, it starts to attract significant amounts of external research funding. James said that the most productive clinical development team at Intermountain, which focuses on women and newborns, published 23 peer-reviewed articles in 2013, while the three cardiovascular teams together published 64 peer-reviewed articles. The point of highlighting this productivity, he said, is that Intermountain’s internal research effort is outperforming most academic institutions. His goal, he added, is that Intermountain’s clinical development teams publish 1,000 peer-reviewed Level 1 publications in a single year.

Level 2 research is the standard academic model of grant-funded, investigator-initiated research. James said that if someone proposes a major research project that has significant external funding but does not fit with Intermountain’s list of internal priorities, he will turn that project down. “It is not the money, but the intellectual capital, the time and attention needed,” he said. Level 3 research involves multicenter trials and other forms of collaboration with external investigators and local universities. Each Level 3 project requires an internal champion. Level 4 research is funded by and conducted for industry-based groups, such as pharmaceutical companies and device manufacturers. Level 5 research is done by affiliated medical staff who are independent of Intermountain.

In summary, James offered three ideas for driving sustainability. First, make the business case. “That means you are going to have to explicitly track cost outcomes in every study that you perform,” he said. In his case, he benefits from Intermountain’s activity-based costing system, which generates patient-level data. His second idea was that data collection should be embedded in the normal workflow, which he said is essential from both an operational and a research standpoint. James’s final suggestion was to make the case to senior management that this research is just part of routine operations and that it should be funded as such. He closed his remarks with an old Yiddish proverb: Better has no limit.

EVALUATION AND IMPROVEMENT OF CARE DELIVERY

In his remarks, Thomas Garthwaite spoke about how to conduct and sustain the type of research that James discussed in health systems that are not at Intermountain’s level of development, which would include doctors and community hospitals that are not part of a system. HCA, he explained is a large system containing primarily community hospitals, with only 2 of its 165 hospitals being academic medical centers. HCA credentials 65,000 physicians, although only about 30,000 are active at any one time, and about 3,000 of these are employed by the hospital. Garthwaite noted that employed physicians are not necessarily engaged physicians.

HCA’s program to partner with physicians to detect and reduce unintended variations in care, both between patients and from the standard of care, is called Clinical Excellence. When this initiative began, HCA executives were worried that suggesting that the quality of their care could be improved might prompt physicians to take their patients to other hospitals. The challenge, then, was to create a data-driven quality-improvement program in a way that engaged physicians rather than driving them away. A pilot study in Nashville, Tennessee, showed that physicians responded positively to accurate, data-driven feedback on how they were doing, coupled with dialog based on the evidence in the medical literature. In fact, Garthwaite said, HCA found that when physicians were engaged in this manner and the changes they suggested were implemented, they became leaders in creating and leading system improvement.

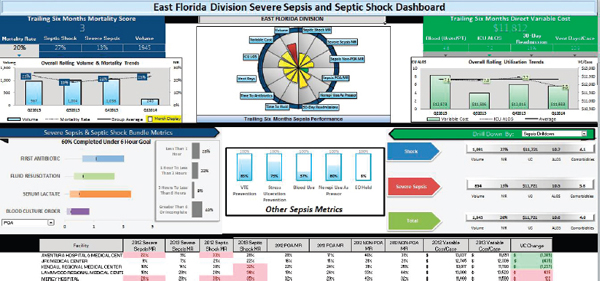

The Clinical Excellence initiative that Garthwaite and his colleagues are creating at HCA starts with metrics generated by its substantial data systems that are focused on where variation occurs. From these metrics, teams at each facility decide which areas they want to target and then work to support preparation, implementation, and tracking. When teams in the field have a question, HCA staff members conduct a review of the literature about the specific topic in question, and the teams then set a targeted performance level using the literature to set what is a realistic goal regarding

clinical performance. A critical part of this process is structuring a plan and supporting it with members of a project management group that is dedicated to this purpose. Data that measure the progress are then displayed in near real-time on a dashboard (see Figure 5-2) that measures, tracks, and guides the management of clinical performance and provides continuous feedback, to both the physicians and management.

Garthwaite said that partnerships with government agencies, academic institutions, professional organizations, and patient-centered nonprofit organizations play an important role in developing and sustaining a learning health care system for community hospitals. As an example, he discussed a project conducted in partnership with the March of Dimes that looked at the elective induction of deliveries before 39 weeks of gestation. This study, using HCA system data, showed that babies born at 37 and 38 weeks had a significantly higher risk of requiring admission to the neonatal intensive care unit. HCA published the results of this study (Clark et al., 2011), and guidelines based on the study have been adopted by The Joint Commission and most insurers.

Concerning business imperatives, Garthwaite said there are a number of factors that can contribute to sustainability. Reiterating something that had already been stated by other speakers, Garthwaite said that good quality care is the most effective and efficient care, with reduced variable cost. HCA’s work has led to the increased use of high-value medications, reduced complications, and shorter lengths of stay. Another benefit from a business perspective is that nurses who become active participants in this research feel more valued and proud of their efforts, which improves both retention and morale. Reputation enhancement is another benefit that can help grow market share.

Garthwaite said that he believes it is important to create an accountability structure that reviews progress on a regular basis. “It is critical that the improvement in outcomes is measured, shared, and celebrated,” he said. Quantifiable quality and economic impacts provide feedback to physicians and management.

Concluding his remarks, Garthwaite said that a key challenge for the future will be developing real-time decision support that is valued by physicians and other providers because any investment in their time is offset by an improvement in the quality of care. He said that creating decision-support tools that can meet those requirements will be important for driving evidence to the bedside and identifying the most effective treatments.

IMPROVING CARE FOR ME AND PATIENTS LIKE ME

The focus of Sally Okun’s talk was an equation that she believes leads to a new way of thinking about how patients and patients’ perspectives can

FIGURE 5-2 HCA’s dashboard links performance and outcome.

SOURCE: Reprinted with permission from Thomas Garthwaite.

have the most significant impact on a sustainable learning health system. This patient-centric value equation states that shared data plus shared decision making equals shared accountability, and it can be applied to every level of the health care system, from the patient level to the institutional level to the community. “Without patients, you will not have a continuous learning health system, and if we don’t embrace that notion right from the start, we are probably not going to get very far,” Okun said.

Okun’s company, PatientsLikeMe, has been in business since 2004 and currently has more than 250,000 patients with some 2,000 conditions reporting to the site. PatientsLikeMe is research oriented and research based, and Okun said that what patients want from research is to believe that the health care professionals who participate in research are going to bring the knowledge that they gain from that research to bear on their care. She added that surveys have shown that most individuals would share their medical information if it was going to be used to improve their health or someone else’s health. However, when Americans are asked if they believe that this is actually happening, most say they do not know. “I think we have a long way to go to help patients and families in our communities to begin to understand that research actually is something that they should be engaging in,” Okun said, “but we should also give them the opportunity to engage in it seamlessly.” She suggested that research should be part of the routine of care and that patients should take it for granted that they are participating in a learning health system on a regular basis.

Sarah Greene had mentioned earlier that patients do not like the idea that the health system is still learning. What would help alleviate that concern, Okun said, would be to convey the message that the health system is learning from each patient so that health care professionals can do their job to the highest degree of excellence. The fundamental question that PatientsLikeMe tries to answer for patients pertains to this issue: Given my status and data, what is the best I can hope to achieve, and how am I going to get there?

Okun explained that basing decisions on the patient-centric value equation does not imply that clinical data should be shared with patients so that they can make informed decisions and get some outcome. What it does imply is that the patient and physician should each share data in a way that enables them to come together to understand potential benefits and burdens of a particular course of action and how those will impact the ability to achieve the desired outcome.

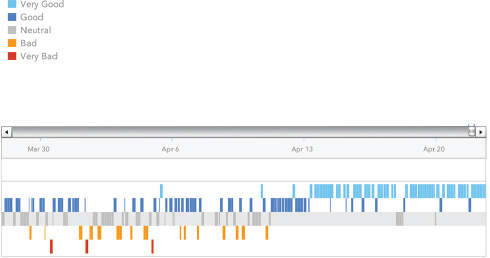

Most health care systems, Okun said, do not have a mechanism for systematically collecting patient-generated data. “We all collect data about what patients say, but not in a way that helps us learn much about the next patient that might come along who maybe had the same subjective experience of that same chief complaint,” she said. “My charge here is to suggest that we can quantify patient-generated data in ways that let us aggregate

FIGURE 5-3 PatientsLikeMe’s InstantMe history tool for a patient with bipolar disorder.

SOURCE: Reprinted with permission from PatientsLikeMe, Inc.

it, collect it, learn from it, and then ultimately we have measured it in such a way that we can then apply it broadly.” Okun suggested that it would be powerful indeed if it was possible to bring together patient-generated data and clinical data in a systematic way that would inform decision making for individual patients.

Referring to the last part of the equation—shared accountability—Okun said that too often the expectation is that patients cannot rise to the occasion when it comes to accountability. “I’m going to challenge you to accept that they definitely can,” Okun said, adding that she had drawn that conclusion from what she and her colleagues see every day on PatientsLikeMe, where patients provide data on what it is like to live with a wide range of conditions. She added that the shared-accountability piece is important because medical care is not about the clinician getting a good outcome—it is about the patient getting a good outcome in the specific context of each patient’s life.

PatientsLikeMe spends a good amount of time looking at reported outcomes from patients to see if there are clinical endpoints and surrogate endpoints in order to learn if particular types of patients report side effects and outcomes. One of the simplest tools it uses with every patient is the InstantMe tool, which asks one simple question: “How are you doing?” Patients record the answer to that question one or more times a day and bring this information into their clinical encounters (see Figure 5-3). Patients report that this format brings their information to life in a way that their health care professionals can easily assimilate and use.

As a final message, Okun said that patients want to see their data coming to life in a way that is useful to their clinicians. What she would like to have happen is for the health care community to come to PatientsLikeMe and work with it to design tools that will help it better understand what patients are experiencing in their lives away from the clinic. “If you begin to embrace that notion,” she said, “you will find that patients are ready, willing, and able to participate in a variety of questions and research studies that you might have in mind and that actually could bring insights that you will just never get in any other way.”

LEVERAGING DATA FOR IMPROVEMENT

Karen DeSalvo started her talk by saying that Okun is right about patients knowing quite well what is going on with them and that asking them one simple question—How would you rate your health?—can help predict how that patient will do going forward. “Of all the things that we can capture and know,” she said, “please don’t forget what patients are trying to tell us because it is as powerful as what we can capture.”

DeSalvo then described the Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology (ONC), an agency formed in 2004 as a way to develop a national strategic plan and approach to health information technology. There was an infusion of capital associated with the economic stimulus and passage of the Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health, or HITECH, Act, which charged the agency to work with the private sector on building an infrastructure that would allow for standard data capture across the health care environment for certain eligible providers. Money was also made available to build the workforce that would manage this system and help utilize the resulting accumulated data. DeSalvo noted that 9 out of 10 hospitals have had the opportunity to participate in the meaningful use program, with the result that there is now rapid uptake of certified, standardized EHRs in the United States. This, she said, is a dramatic increase compared to other nations that have not made this type of investment.

DeSalvo said that it is increasingly clear that some parts of the health care continuum do not have the opportunity to contribute to the grand amount of data in the nation’s learning health systems. “Importantly, that is where some of the most vulnerable and some of the most expensive patients are in our community,” she said. Reaching those places, which include long-term post-acute care facilities, behavioral health, dialysis, the emergency medical services sector, and some of the smaller health systems that are not capturing data on the scale of an Intermountain Healthcare or HCA, is a national imperative because without the entire picture, it will be a major challenge to achieve the triple aim of having better care at a

better price and improving the health of the population as a whole. It has also become clear, she said, that there are opportunities to improve the usability of EHRs in ways that will increase safety and enable clinicians to do their jobs better.

Interoperability is a priority for ONC, DeSalvo said. “We must create an infrastructure that is open enough that if you collect information in your database, in your health care environment, whatever that might be, that it can be free and flow to the benefit of that patient across the care continuum,” she said. This is challenging work because it requires defining the right standards and building the right systems so that they are sustainable over time and not just experiments in closed systems. It requires defining privacy and security in a way that is palatable to everyone, that protects people and their data, and yet that allows the data to be put to good use. It also requires creating the right governance infrastructure, which involves coming to some agreement about who gets into the system and who does not and what happens to those who do not follow the rules.

DeSalvo ended her remarks with some words of caution concerning big data. “Big data is really tempting,” she said. “It is tempting to anyone in the private sector to begin to play with, but you need to walk into this with some a priori hypothesis that is testable. Let’s be careful with how we are using this data.” She also said it is important to be thoughtful as the PCORnet infrastructure is being developed about not over-burdening the frontline health care professionals because, at the end of the day, it is a health care system and its foremost responsibility is to care for patients. “We certainly want to make sure that we are not over standardizing and structuring data in such a way that we lose context and narrative or prevent that care environment from being the rich place that patients and providers so enjoy,” DeSalvo said. Returning to her initial comments, she again stressed how important it is to capture the rich and valuable information that patients have to contribute.

To start the discussion, session moderator Sandy said that the message he heard from the presentations was that there are two models for sustainability. The first had as its value proposition what he called “acceptable cost, reasonable value.” With this model, the activities of a learning health system are not too costly, and they produce some value. Some of that value is easy to measure, some not, and some could tie into an organization’s nonprofit status. The key is that these activities are not a big strain on the budget, and that makes them sustainable. The second model of sustainability, Sandy said, is one in which the continuous learning and improvement system should pay for itself and be a contributor to return on investment.

James and Garthwaite both agreed with Sandy’s assessment. James went on to say that that Intermountain Healthcare’s efforts are based on the second model. He said that the system’s chief financial officer set a goal that its learning activities should produce enough return on investment so as to limit the health plan’s rate increases to no more than 1 percent above the consumer price index by 2016. Intermountain nearly met that goal in 2013 and has likely surpassed it in 2014. He noted that in 2013, six projects alone accounted for $39 million in savings. Where this type of activity will not work well is in a fee-for-service system, which actually punishes these kinds of improvements because they reduce utilization. “That is why Intermountain is shifting to a capitation model as rapidly as we reasonably can,” James said. He also said that there is now an opportunity to apply this model to the entire health care system and noted that it would have a tremendous financial impact if it avoided even half of the estimated $1 trillion in wasted expenses the nation spends annually on inefficient and ineffective procedures.

Jeremy Boal of the Mount Sinai Health System said that he is impressed by the handful of health systems that seem to have operationalized this second model and that have built return on investment into the core of their operations, but he wondered why so few health systems are following in these pioneers’ footsteps. “What is holding us back,” he asked the panelists, “in being able to make the kinds of transformations that you and a few other key organizations have been successful in making?” James replied that he believes that the key is to spend the time and effort to build an infrastructure, which includes data systems, that makes it easier to accomplish an organization’s goals and that provides transparency to both patient and clinician. “If you build the right infrastructure, it makes it easy to do it right,” James said.

James Rohack of Baylor Scott & White Health commented on the difficulty in getting different EHR systems to talk to one another, which even extends to the U.S. Department of Defense and VA systems not being able to communicate with one another. The question he had for DeSalvo was that, given that ONC is coming out with rules and regulations that the federal government cannot seem to implement itself, “What is the solution, and when will we see that these electronic systems will be able to talk to each other?” DeSalvo, who had been at ONC for only 3 months at the time of the workshop, replied that she understood his frustration from her own experiences as a physician dealing with different EHRs but said that the success story so far is that there are now data that are available to be shared, thanks to the standards that ONC has developed. The goal for ONC now, she said, is to work with the private sector to decrease the technical optionality that makes interoperability so difficult and to develop an open architecture for data exchange. DeSalvo also said that the govern-

ment has not given up on getting the U.S. Department of Defense and VA systems to be interoperable and that she is intent on making that happen.

DeSalvo went on to say that ONC’s efforts now are focused on identifying a core set of information that matters for patients and clinicians in much the same way that physicians do when they prepare index cards for each of their patients that they carry with them. “We have to get focused and serious and parsimonious about what it is that matters,” she said. “What are the measures that matter? What are the core pieces of information that matter for the clinical environment that we need to share? That begins to simplify the conversation about interoperability.”

In response to a question about why more work is not being done to reduce fixed costs, given that they account for 70 to 80 percent of a health system’s budget, Garthwaite said that one reason is that variable costs are more easily calculated for specific interventions. Having said that, he added that there are opportunities to reduce fixed costs, perhaps by limiting the “technical arms race,” where each hospital feels it needs robotic surgery capabilities to remain competitive in attracting the best surgeons. James said that Intermountain does track fixed costs, and he estimated that over half of the savings his group has realized are from fixed costs. For example, Intermountain’s initiative to reduce elective labor inductions saved approximately 45,000 minutes in labor and delivery time, enabling the system to deliver some 1,500 more babies each year without adding any capacity.

Bray Patrick-Lake, the patient representative on the PCORnet coordinating center executive leadership committee, asked James if Intermountain involves patients in setting the priorities that determine which research projects are approved and which are rejected. James replied that each of the clinical development teams, which set the research agenda, involve patients directly. Patient input is also an important part of Intermountain’s clinical operations, he added. Patrick-Lake also asked James how Intermountain balances the speed of implementation against the time it takes for research to be published in the peer-reviewed literature. James said that Intermountain is not very good at publishing because it is not an organizational priority—implementation is. “As soon as we get the answer, it’s on to the next question,” he said.

After some discussion that reiterated the message that patients have a great deal to contribute to a learning health care system, Okun said that it is important for the research community to understand that patients will be intolerant of research that does not go anywhere. “They want to see some outcomes that are going to benefit them,” she said. James agreed strongly. “Any organization that does not put the patient outcomes first should not be allowed to treat patients,” he said. “If your research comes before your patient outcomes, you should not be allowed to treat patients.”