In his keynote address, Manuel Pastor, a professor of sociology, American studies, and ethnicity and director of the Program for Environmental and Regional Equity (PERE) at the University of Southern California, described his research and shared his personal insights about the power of communities that participate in improving their collective health. PERE, he explained, was founded to support and directly collaborate with community-based organizations on issues of social justice.1 PERE conducts research and facilitates discussions on issues of environmental justice, regional inclusion, and social movement building.

ENVIRONMENTAL JUSTICE: SCREENING FOR HAZARDS WHERE PEOPLE LIVE, WORK, LEARN, AND PLAY

The San Francisco Bay area in California has been the site of a great deal of community-based environmental justice activity over the past decade. Because there had not been any systematic study to identify patterns of environmental impact in the area, Pastor and colleagues entered into a multiyear relationship with 35 different environmental and public health groups to form the Bay Area Environmental Health Collaborative (BAEHC), which set out to document environmental disparity in the Bay Area. A report prepared for BAEHC, Still Toxic After All These Years, mapped the hazards in the Bay Area relative to the surrounding communities and the health of the people living in them (Pastor et al., 2007).

____________

1 For more information see http://dornsife.usc.edu/pere (accessed August 15, 2014).

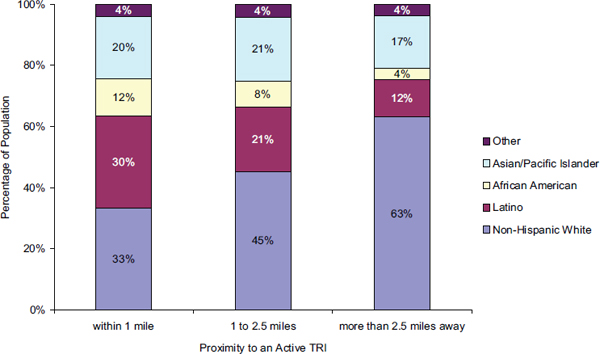

The first step of the project was to map neighborhood demographics against a toxic release inventory (TRI) that had been conducted by the federal government. Pastor and colleagues found that two out of every three people living within 1 mile of industrial facilities that release toxic substances were people of color (Latino, Asian/Pacific Islander, African American, or other; see Figure 2-1). Of those living more than 2.5 miles away, only one out of three were people of color (see Figure 2-1). From an economic perspective, housing located near these TRI sites is of lower value, and people with higher incomes are less likely to live near such facilities, but, Pastor noted, even after taking into account these income-based disparities, racial disparities were still apparent at every income level. In addition to preparing an academic paper on the use of this spatial autocorrelation approach in environmental justice research, Pastor and colleagues released a draft report at a scientific meeting, wrote an opinion piece in the San Francisco Chronicle, and held a press conference at a refinery in Richmond, California, with the community groups in the collaborative. Community organizers expressed their concern that the technical nature of the report would make it difficult for others to understand the significance of the work done by the researchers and community groups. Importantly, Pastor said, it was a community organizer trained by

FIGURE 2-1 Population by race/ethnicity (2000) and proximity to a TRI facility with air releases (2003) in the nine-county San Francisco Bay area.

NOTE: TRI = toxic release inventory.

SOURCE: Pastor presentation, April 10, 2014, from Pastor et al., 2007.

Pastor and his colleagues who presented the final research report to the members of the collaborative. This fostered an environment of “each one teach one,” Pastor explained, and community organizers actively helped bring the science into the debate, raising the issue of cumulative impacts with policy makers.

BAEHC’s next step, Pastor said, was to move beyond documenting disparities to effecting change. With support from the Air Resources Board (of the California Environmental Protection Agency), an environmental justice screening methodology was developed to identify communities that may be disproportionately overexposed to pollutants. Pastor noted that this is a screening tool, not an assessment tool; that it is currently focused primarily on air quality; and that it relies on available secondary databases (e.g., state and national data on environmental hazards, modeling from emissions inventories, census data). Communities were screened according to three categories of cumulative impact: proximity to hazards, exposure to health risks, and social and health vulnerability. Scores in these three categories were used jointly to assign a cumulative impact score to a community and to identify regions to target with more community outreach.

This environmental justice screening tool, Pastor said, was the forerunner for what the state of California now calls CalEnviroScreen, which is being used statewide to identify communities that are environmentally overexposed and socially vulnerable. This approach to screening has also been important in the debate about how best to invest the proceeds from California’s cap-and-trade program to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. According to the law that established this program, 25 percent of the revenues generated by it must go to disadvantaged communities.2 CalEnviroScreen has provided a tool that community organizations use to argue for additional attention, to suggest metrics, and to demand progress.

Pastor stressed the importance and value of community engagement in the development, review, and use of the screening tool. He noted, however, that the process was filled with “numerous inside–outside tensions,” including concerns from the state agency concerning the degree of openness with the community groups about the development of the method. Pastor said that agencies are starting to realize that an open process leads to greater public acceptance of the outcomes. In addition, when opportunities are created for people to participate through focus groups and through community-based participatory research, people start to moderate their own views and begin to find common ground.

____________

2 SB-535 California Global Warming Solutions Act of 2006: Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund, Chapter 80, approved September 30, 2012. Available at http://leginfo.legislature.ca.gov/faces/billNavClient.xhtml?bill_id=201120120SB535 (accessed July 15, 2014).

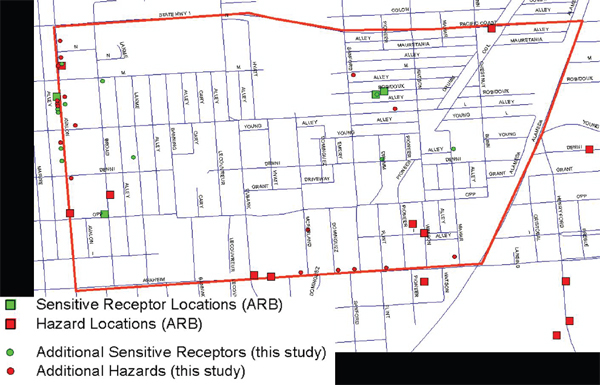

A parallel part of the process was educating and organizing community leaders around their environmental justice concerns and ground truthing the data (CBE, 2008). Pastor described ground truthing as a process in which teams of community members go out into the neighborhood to determine whether the official data on hazards are accurate. For example, hazards in the databases may no longer exist, new hazards may not be in the databases, or sensitive receptors in the community (e.g., informal day care centers) may not have been entered into official databases.

To further explain ground truthing, Pastor described a case from Los Angeles. A variety of hazard and sensitive receptor locations in the Wilmington neighborhood of Los Angeles are listed in the state database (see Figure 2-2, shown as squares), but a walk around the neighborhood by community members revealed additional hazards not included in the database (e.g., parked diesel trucks, brownfields, junkyards, and auto body shops) as well as several additional sensitive receptor sites (see Figure 2-2, shown as circles). The second phase of the ground-truthing exercise involved air monitoring. The results of ground truthing in eight Los Angeles communities were released in the report, Hidden Hazards, which was featured in the Los Angeles Times newspaper and on television

FIGURE 2-2 Hazards and sensitive receptor locations in the Wilmington neighborhood of Los Angeles as identified in state databases (squares) and from a community ground truthing exercise (circles).

SOURCE: Pastor presentation April 10, 2014, adapted from a figure created by his colleague James Sadd.

(LACEHJ, 2010). Following the release of the report, four City Council members introduced a resolution to create “green zones” in overexposed neighborhoods of Los Angeles. Pastor noted that community members were very engaged and spoke before the City Council about their experiences with ground truthing, arguing in support of the resolution. Now in its early stages, the Clean Up Green Up initiative is focused on reducing and preventing pollution, developing additional park space, and revitalizing neighborhoods.3

AUTHENTIC COMMUNITY ENGAGEMENT

Using insights gained from these and other equity projects, Pastor shared his perspective on community engagement, community organizing, crafting the narrative, and fostering change for better community health. Engagement, he said, is often done in one of two ways: the “Potemkin way” or the “Kabuki way.” Like a Potemkin Village, public engagement is often just for show. The decisions have already been made, and the engagement process is perfunctory. Engagement can also be similar to the stylized drama found in Kabuki theater, with staged conflict, dueling experts, and no clear search for common ground. Authentic engagement, Pastor said, involves community-based participatory research, ongoing dialogue with the community for the entire length of the project, and structures explicitly focused on reaching out to those least powerful in the process.

Community organizing involves projects, policy, and power. Research projects demonstrate what is possible, Pastor said, and policy is changed based on the results of that research. But without a constituency demanding policy changes, no changes will occur. For too long, Pastor said, foundations and academics have focused on demonstration projects, but demonstrating that something works does not mean it will be replicated or implemented. Pastor said that change in policy requires power, and power involves community organizing to build the voice of community. Pastor further explained that organizing is about shifting power to the community. It is long, hard work, he said, and it is both a science and an art. Community organizing takes a village, or an ecosystem, in which multiple groups play a role.

A clear narrative is also essential, Pastor continued. Research focuses on facts, but the facts need to be attached to a personal story and to be conveyed in a manner that is easily understood. The focus is often on one particular issue, rather than a deeper, transformative vision. When active members of the community speak about environmental justice, they are not just speaking about removing hazards from their community; they

____________

3 For more information see http://cleanupgreenup.wordpress.com (accessed August 15, 2014).

are speaking about transforming their communities into thriving, green places where they can live, work, learn, play, and prosper. Whatever the issue, Pastor said, it is necessary to have a narrative, a broader vision, and an understanding that community engagement convinces people of their voice and power.

Communities have inherent knowledge about issues, and they have wisdom that can be effectively coupled with science, Pastor said. Allies need to be humble in recognizing the value and role of community wisdom and confident about the research skills they bring to the community. Pastor added that often the underlying health issue in a community is a lack of power—power to get the resources needed to address whatever problems there are. In conclusion, Pastor said that community organizing is good not only for community health, but also for individual health because it builds social bonds among people, empowering them to get through adversity and make it to the next stage.

During the brief discussion that followed, Pastor expanded on the concept of organizing as creating an ecosystem, and individual participants discussed the issue of scale.

Community Organizing as Developing an Ecosystem of Partners

The traditional view of community organizing has been that the best approach is to create one organization or group on the basis of an interest. Pastor suggested that it is more effective to organize people based on their values, not their interests, and to develop an ecosystem of groups that can work together to transform the policies in an area. Focusing on values also helps to create a more compelling narrative. As an example, Pastor described the Community Coalition of South Los Angeles (CoCo),4 which was originally formed to combat the crack cocaine epidemic in the area. After polling the neighborhoods, CoCo learned that residents were more worried about liquor stores as neighborhood hazards (especially people congregating around liquor stores), so the coalition took up that issue as well. Over time the coalition has become a powerful force for taking back the neighborhood through efforts such as improving parks and educational infrastructure. CoCo has also recognized the need to help develop and support an ecosystem of high-performance groups by partnering with other entities such as InnerCity Struggle in East Los Angeles.5

____________

4 Discussed further by Harris-Dawson in Chapter 4.

5 Discussed further by Willems Van Dijk in Chapter 3.

CoCo’s efforts to transform education in South Los Angeles will only be successful in partnership with a similarly strong effort to reform education in East Los Angeles.

Pastor also said that when he and colleagues are approached by representatives from communities outside Los Angeles who wish to work with them, he instead helps them build research university–community partnerships with universities in their own regions, such as the Central Valley. Pastor has provided guidance on initial reports, but he emphasized that this is “an ecosystem approach, not an empire approach.” Rather than doing the work themselves, Pastor and his colleagues build capacity and make the movement stronger by passing the work on to others. An ecosystem involves community organizers asking themselves such questions as, Who are our partners? How can we strengthen our partners? and, How can we strengthen our networks? Pastor stressed the importance of academics supporting communities in conducting rigorous research and in developing relationships with technical people inside government agencies. Academics can play an important role in this form of inside organizing by reaching out to technical people who can verify that community data, methods, and claims have merit.

Scale

A participant raised the issue of scale, noting that while there are pockets of community engagement and organizing around the country, there are many areas where there are no such efforts. Pastor responded that bringing these efforts to scale involves thinking about power statewide and about where things can be changed. He noted that an alliance of community groups under the banner California Calls has worked to bring engagement to scale by mobilizing new and occasional voters and by targeting potential voters in areas that would not normally be targeted. Organizers walked around neighborhoods and asked people what they would like to see California become—in essence, tapping into their values and dreams. Community organizers need to scale from neighborhood to region and then to state.

Several of the participants also discussed the role of social media in scaling the movement. Pastor noted the need for both traditional “high touch” organizing and “high tech” online organizing in order to reach the ultimate goal of mobilizing people. What has not been scaled, Pastor said, is the academic/research side, which is a complementary part of the ecosystem. In this regard, he has been working on an initiative to institutionalize progressive, community-engaged research centers within universities throughout California (Sacha et al., 2013).