In consideration of the various tools and approaches addressed in previous chapters of this report, this chapter discusses the evolving framework for sustainability and EPA decision making, including opportunities to make sustainability the integrating core of the agency’s strategic planning process and embedding the use of sustainability tools into its activities.

Throughout the history of the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), various major decision-making frameworks have guided policy choices covering a variety of public-health and environmental issues. In the agency’s formative years, the frameworks included the application of technology-based standards to restrict emission and effluents from specific sources or source categories; the development of health-based standards to protect drinking-water supplies or ambient-air quality; and the establishment of registration processes and application rates for pesticides and their designated uses. Those and other decision-making frameworks constituted a response to statutory requirements and an expression of the evolution of institutional practices among agencies that preceded the formation of EPA (Portney 1978; Lave 1981).

The publication of the National Research Council’s 1983 report Risk Assessment in the Federal Government: Managing the Process was another major inflection point in EPA’s decision making frameworks. The formalization of risk assessment and risk management processes had been evolving in EPA in the 1970’s, but they received more direct and official codification by a series of policy pronouncements issued by several EPA administrators in the 1980s and beyond (NRC 1983).1 Rather than displacing earlier frameworks however, the risk-assessment–risk-management paradigm added to the scientific tools and approaches used by EPA in implementing its statutory authorities.

Through a combination of statutory changes or through its own initiatives, additional frameworks and approaches continued to supplement EPA’s policy toolkit through the 1980s and later years, including:

• The adoption of pollution prevention as a method for examining pollution-reduction opportunities before the point of effluent, emission, or waste generation or discharge.

• The development and implementation of incentive-based offset and “cap and trade” control measures (plant-specific and regional) for such issues as acid-deposition precursors, including nitrogen oxides and sulfur oxides.

• The establishment of an expanded number of voluntary initiatives aimed at accelerating the reduction of toxic emission, expanding energy efficiency, and other objectives.

• The initiation of cross-statutory or multisector initiatives that aspired to identify and manage tradeoffs among statutes to maximize both environmental protection and economic efficiency.

____________________

1EPA’s Science Advisory Board provided further guidance to EPA in using risk-based decision-making in its report Reducing Risk: Setting Priorities and Strategies for Environmental Protection (EPASAB 1990).

• The development of more robust initiatives with state and local authorities to address regional air-quality and water-quality problems (such as ozone and fine-particle pollution in the mid-Atlantic and Northeast corridor and regional watershed-management planning for the Great Lakes or Chesapeake Bay).2

In recent years, EPA has begun to examine and introduce elements of sustainability-related thinking into research and development, method development, federal procurement guidelines, and strategic planning. For example, EPA’s FY 2014–2018 strategic plan incorporates a number of sustainability-relevant initiatives into the agency’s five Strategic Goals, Cross-Cutting Fundamental Strategies and Strategic Measurement Framework (EPA 2014a).

EPA’s decision making frameworks function in parallel and are in various states of transition, but they are not in integrated relationships with each other. In that respect, EPA’s FY 2014–2018 strategic plan mirrors those discontinuous relationships, and it is unclear how the decision making frameworks support each other in executing the agency’s mission. Given that each decision making framework has its own set of implementing tools and methods, it is important that EPA achieve greater internal consistency, clarity, and priority-setting among these tools and their applications.

EPA should consider the present transition in its decision making approaches as an opportunity to evolve towards making sustainability the integrating principle of its strategic planning process. The committee urges EPA to continue in its efforts to adopt or adapt the sustainability framework presented in Sustainability and the U.S. EPA, the so-called Green Book (NRC 2011a). (Recommendation 7a)

The advantages of such an evolution include:

• Enabling EPA to achieve greater clarity of purpose in its various regulatory and non-regulatory programs.

• Aligning the agency’s sustainability tools and approaches and their implementation with global, regional, and local megatrends; market developments; and stakeholder leader expectations.

• Gaining access to newer tools and methods that have emerged in recent years from private sector and non-government organization (NGO) partnerships, universities, and other stakeholders (examples of some of the tools and methods are cited and illustrated in the present report).

• Building new relationships with thought leaders in multiple institutions to design innovative sustainability tools.

• Providing greater clarity and understanding of EPA’s mission and value to the American people at a time of public uncertainty over many public-health and environmental issues and EPA’s role in resolving them.

Numerous government reports, scholarly analyses, and private-company investments attest to the growing importance of mitigation and adaptation strategies necessary to respond to problems as varied as climate change, natural-resource scarcities, public-health protection, and building of more sustainable communities.3 As the concept of adaptation advances, there are direct implications for how government

____________________

2EPA’s Common Sense Initiative and Project XL were prominent examples of these types of initiatives in the 1990s.

3Examples of such reports include City of New York 2014; IPCC 2014; World Economic Forum 2014.

agencies and private-sector organizations need not only to revise policy frameworks but to recast their own institutional capabilities, resilience, and assessment and implementation tools in a clear and predictable manner that is consistent with their missions and responsibilities.

In EPA’s 4.5 decades of existence, there have been many instances in which it has adapted its identification of priorities to recognize new generations of problems (for example, naturally occurring exposures to radon gas and the phaseout of chlorofluorocarbons and successor chemicals to protect the stratospheric ozone layer), modified its implementation strategies to take account of innovative thinking (for example, emission trading and offset initiatives and agreement for testing of high-production-volume chemicals), and developed new tools and approaches for managing public-health and environmental challenges (for example, the formalization of risk-assessment guidelines and the development of a risk-screening model to identify potential risks earlier in the chemical-development process and to encourage substitutions).

EPA has a major opportunity to embed sustainability considerations further in its decision-making methods and to communicate and disseminate its application of sustainability tools and approaches outside the agency. EPA should pursue this embedding throughout the agency. (Recommendation 7b)

The committee has identified four kinds of major activities (derived from Table 2-1) in which EPA has substantial opportunities to apply sustainability tools and approaches to the extent practicable under budget constraints. Each is consistent with the agency’s existing statutory authorities and, in fact, builds on initiatives previously implemented.

Setting and Enforcing Regulatory Standards

Furthering the incorporation of sustainability as a core principle of EPA’s mission includes consideration of fundamental public-health and environmental protections related to a suite of air, land, and water issues that are administered at the federal, state, and local levels of government. To ensure effectiveness and accountability, baseline standards and their enforcement are periodically reviewed to account for new scientific information, technologic innovation, and reviews of program effectiveness. Supplemented by such tools as data-quality management, risk assessment, life-cycle assessment (LCA), economic analysis, peer review, management systems, public participation, and other forms of transparency, EPA’s standard-setting and enforcement roles provide an important basis of additional efforts in advancing toward more sustainable health, environmental, and economic outcomes. That approach is similar to that used in the private sector, in which sustainability strategies and initiatives have been designed and implemented on the basis of an original structure of environmental, health, and safety policies and management systems.

As part of its continuous strategic planning efforts, EPA should consistently review opportunities to insert sustainability concepts, tools, and methods to strengthen evaluations of its existing regulatory policies and simultaneously apply these sustainability approaches to emerging challenges. (Recommendation 7c)

In any discussion of standards (regulatory and nonregulatory)—whether they are outgrowths of statutes, outcomes of deliberations of professional bodies (such as those developed by the International Organization for Standardization), or results of obtaining consensus about best practices related to specific issues (such as pollution prevention)—the critical barometer of success is the outcome of application of the standards. Standard-setting is a core role of EPA, not merely through the implementation of its statutory authorities but through collaborative efforts with other organizations to address the suite of sustainability challenges related to its mission.

One of the critical future challenges to both EPA and the private sector will be the need to increase the scale of its environmental and quality-of-life improvements. Individual companies, even when successful, are limited in their scaling potential by the individual markets that they serve.

EPA—in collaboration with the private sector, NGOs, multilateral institutions, and other national governments—should evaluate existing best practices to identify opportunities for increasing the scale of the benefits of sustainability decision-making within the United States and around the world. (Recommendation 7d)

Managing and Synthesizing Data

EPA is responsible for collecting, managing, and interpreting a number of diverse databases for a variety of policy decisions. These efforts range from support of air-quality monitoring stations to evaluate compliance with National Ambient Air Quality Standards in specific air sheds, review of water-discharge data to assess compliance with National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System permits, analysis of data submitted by chemical manufacturers to assess whether to allow new chemicals to enter the marketplace under the Toxic Substances Control Act, and the collection and publication of Superfund Amendments and Reauthorization Act Title III data.

Beyond program-specific data collection and analysis, EPA has for many years performed the role of data manager and synthesizer. The agency’s Integrated Risk Information System (IRIS) is an international resource for business, government, and the public to gain access to information on individual chemical profiles as a basis for regulatory policy decisions, discussions of community risks, and risk-management decisions taken by individual companies and consumers. IRIS provides a platform for public discussion and exchange of information; it provides access to scientific tools and enables users to link to related databases. Other agencies have adopted the IRIS concept to implement their missions.

EPA has a major opportunity to build on data initiatives, such as IRIS, by becoming a data manager and synthesizer for a growing number of information-management challenges, including

• Synthesizing and interpreting data to aid the investment community—EPA could assist such organizations as the Sustainability Accounting Standards Board and the Securities and Exchange Commission in collecting and synthesizing general-public comments and provide advice on public-health and environmental issues that are material to the performance and governance of corporations.

• Filling information gaps—EPA could collect and aggregate databases that bear on the materials used in the sourcing, manufacture, distribution, and use in a host of consumer products. There are major gaps in individual companies’, government agencies’, and consumers’ knowledge as to the ultimate disposition of economically valuable materials that can also present health and environmental risks if they are not subject to a cradle-to-cradle system of material recovery and reuse. The development of information-management capability would be a critical step in the advance of infrastructure for sustainable material-management policies.

• Monitoring and surveillance to identify problems and trends—EPA could search for patterns and trends among databases that would yield insights into health and environmental outcomes. As owners and tenants of homes, offices, and other commercial buildings begin to install “smart” information technologies that measure energy and water consumption, for example, their measurement devices will provide data that, when aggregated, can yield important information about emission, natural-resource consumption, and other indicators useful to consumers, businesses and service providers, and public-policymakers. Another opportunity for pattern recognition and outcomes analysis lies in the synthesis of a growing number of databases that are reporting greenhouse-gas emission. Improved transparency in shale-gas operations, for example, would yield data and trend analysis that can assist operating companies in working collaboratively to design best practices to capture or prevent the release of methane.

Those instances of data management and synthesis represent important opportunities to expand public and stakeholder engagement in decision-making for environmental sustainability. By becoming a greater catalyst for transformational transparency, EPA can unlock new opportunities for innovation in the application of publicly available information and for developing methods applicable to its own and stakeholders’ needs. Chapters 4 and 5 of this report provide specific examples of how the private sector and other institutions have made use of these opportunities—and the associated tools that support them—to improve sustainability outcomes.

Convening for Collaboration for System-Level Solutions

A growing number of major sustainability challenges transcend specific environmental media or markets. For example, attempts to reduce or eliminate the disposal of residua in landfills depend increasingly on collaboration among a variety of important economic decision-makers, including providers of raw materials, packaging companies, and producers, retailers, and consumers of manufactured goods. No single institution or group has the capability to design an effective solution to reduce or eliminate the landfilling of such residua. Instead, an empowered convener has the opportunity to leverage the various parties involved in related economic activities for the common good.

There are structural impediments to the private sector’s ability to serve in such a convening role. They include antitrust considerations, competitive interests that militate against the direct disclosure of information to rival companies, and periodic public skepticism about the private sector’s credibility or motivation.

Such impediments do not exist when the convener is a major government agency that has legal authority to invite major economic actors and their stakeholders into a collaborative, problem-solving process. EPA’s history contains many examples of its application of convening authority, including voluntary initiatives with companies to report reductions of high-priority toxic releases, acquisition of data from testing of high-production-volume chemicals, development of test methods for identifying endocrine-disruption potential, and conducting formal regulatory negotiations as a precursor to formal rulemaking on such issues as residential wood heaters, equipment leaks from chemical processes, and cleaner fuel development.

Further developing EPA’s role as a convener would have several advantages, including

• Obtaining access to scientific and other data generated by less traditional sources that are relevant to EPA decision-making, such as information from private sector and NGO partnerships, initiatives led by NGOs to develop global standards, and newer consortia of private companies, NGOs, and universities (for example, The Sustainability Consortium).

• Gaining valuable experience in applying sustainability tools and methods. Many private companies and NGOs have taken the lead in applying sustainability tools, including LCA, accounting methods for calculating the social cost of carbon, natural-capital valuation, and assessment of tradeoffs at the climate–water–energy–food nexus of issues.

• Initiating a federal interagency process to develop and apply tools, such as LCA, in a sustainability context. EPA is a lead agency in many interagency forums, including science and technology for environment, natural resources, and sustainability in which science and technology priorities, budgets, and programs are assessed and aligned with policy priorities. The process could include assessments of the best practices, research and analytic impediments, data gaps, case studies of federal agencies’ tools applications, and approaches that would enable the best use of sustainability tools.

• Applying transregional and global scenarios and trends analysis to problem-solving that is within EPA’s specific jurisdiction. The interconnected nature of the global economy requires greater EPA understanding of such scenarios and trends to inform its decision-making on such issues as climate change, recycling opportunities, and green-product development.

• Leveraging existing EPA capabilities to achieve larger-scale outcomes that would greatly exceed the effects of following traditional decision-making approaches. For example, convening the important producers along an entire value chain of the energy market (rather than focusing on emission from the utility sector alone) provides EPA and the public that it serves with the opportunity to use many more tools and options and generate more effective decisions. The cost effectiveness of such an approach is likely to be higher than if single source categories are focused on in isolation.

Expanding EPA’s convening role and capabilities would enable the agency to create new decision-making platforms to achieve critical objectives by applying innovative tools and approaches.

Catalyzing Innovation in Decision-Making

An examination of EPA’s programs yields many instances of innovation in decision-making frameworks and their applications. EPA made early use of economic-incentive approaches that later found application in the 1990 Clean Air Act Amendments, which codified the use of emission offsets to reduce acid-deposition precursors, such as nitrogen oxides and sulfur oxides, at a small fraction of the previously estimated cost. Similarly, support for pollution-prevention initiatives led a number of companies to examine their business processes to identify less expensive, environmentally effective solutions in their operations.

The committee has identified various assessment approaches that could be used to identify new opportunities for incorporating sustainability concepts into EPA’s decision-making.

Developing a Cradle-to-Cradle Approach to Assessing Materials Management4

Many of today’s most important products—appliances, automobiles, computers, electricity, food, mobile telephones, and synthetic materials—are made and consumed without sufficient understanding of their full life-cycle effects or recognition of their full social costs.5 As a result, huge volumes of usable materials go unrecovered and unused because current policies (such as water subsidies) encourage over-consumption or make materials recovery or resource efficiencies uneconomical for many products. Given the span of its responsibilities, EPA is well positioned to examine materials management in various business sectors and develop assessment practices that encourage the application of life-cycle approaches and identification of opportunities for innovative design and development of a materials recovery–reuse infrastructure in multiple market sectors.

Evaluating Pollution-Related Risks and Risk-Reduction Opportunities Throughout an Entire Value Chain and Not Only for Individual Sources

In EPA’s history, there is precedent for this type of thinking, but it has had little application. A major application of this approach occurred in the aftermath of the 1990 Clean Air Act Amendments. EPA was charged with the responsibility to promulgate regulations by 1995 that would result in cleaner fuels by reducing volatile organic compounds and other air toxics. EPA quickly concluded that such a mandate could not be successfully achieved by focusing on petroleum refiners alone, so it convened a process through which many of the major participants in the fuels value chain contributed scientific data, modeling scenarios, and test results of varied fuel compositions and emission performance of various families of fuels and vehicles. The participants included refining companies, chemical companies that supplied fuel

____________________

4For a more extensive discussion of the cradle-to-cradle concept and its applications, see McDonough and Braungart 2002.

5See, for example, NRC 2010.

components, major automotive manufacturers, engine manufacturers, agricultural interests, state and local government officials, and environmental organizations. The result of their deliberations was encapsulated in a formal agreement among most of the participants. EPA converted the accord into a formal rulemaking proposal subject to public notice and comment before a final rule promulgation that was achieved in advance of the statutory deadline.6

There are substantial environmental sustainability challenges along a number of important value chains. Examples include reducing packaging in consumer products, such as clothing, electronics, and food; decreasing the carbon and water footprints of the manufacturing and service sectors; and reducing the carbon intensity and fine-particle emission of the nation’s energy-production system.

Simultaneously, new value chains are being constructed in ways that have major implications for EPA. The automobile industry, for example, is in the formative stages of a historic transformation away from primary reliance on the internal-combustion engine powered by hydrocarbon-based fuels toward more innovative propulsion by electricity, hydrogen, and other alternatives. In the midst of this transformation, EPA’s traditional risk-assessment framework—focused on tailpipe and other evaporative emission from existing fuel combinations—will be less relevant or even rendered obsolete.

EPA should examine various sustainability challenges in collaboration with outside organizations and seek to evaluate risks and optimize decision-making and environmental performance for a number of value chains, both existing and in formation. (Recommendation 7e)

Constructing a Research and Evaluation Template for Sustainable Cities

The historic demographic transition that is under way has already meant that a majority of the US and world population lives in cities. That trend is expected to continue (Portney 2003; Pijawka and Gromulat 2012; Pearson et al. 2014). Providing economic opportunities, infrastructure, and services to the growing urban population poses one of the major challenges to current and future generations. Leading companies, universities, and other thought leaders have initiated plans and programs to prepare for this future and advance the concept of sustainable cities in connection with varied issues, such as commercial and residential buildings; congestion management; health-care delivery systems; optimization of energy, water, and food delivery systems; infrastructure design and investment; and smart technologies

EPA has a number of important responsibilities and leverage points to advance the development of more sustainable cities. They include air and water-quality permitting; remediation practices and requirements; and use of natural systems in addition to human-made infrastructures for combined sewer overflow and storm-water and storm-surge management.

In developing a research and evaluation template for sustainable cities, EPA should explore the application of a broader set of sustainability tools. (Recommendation 7f)

Examples include building on the best practices of cities, such as New York, that have developed widely accepted initiatives for making the energy performance of commercial buildings transparent to architects, engineers, realty companies, building-maintenance and energy-service firms and tenants and creating opportunities for their collaboration to achieve a more efficient use of energy. New York is also a leader in developing plans for mitigation of natural hazards that EPA, in its various authorities, will have a role in reviewing and implementing. Some federal agencies, such as the Department of Defense and Department of Energy, have large land holdings that include small urban centers; these are being man-

____________________

6For example, the regulatory negotiations on Reformulated Gasoline under Title II (Section 211) of the 1990 Clean Air Act Amendments.

aged with consideration of sustainability factors as part of the planning process and may provide insights for EPA and other institutions.

MOTIVATIONS FOR LEADERSHIP BY BUSINESS, NONGOVERNMENTAL ORGANIZATIONS, AND GOVERNMENT

As the landscape of the global economy continues to evolve and global megatrends present major new risks and opportunities, institutions in the public, private, and NGO sectors are re-examining their roles and capabilities. For business, these developments are leading to new business models, accounting methods, and accountability processes that recognize the materiality of risks and effects, innovation and market-access opportunities, and a necessity to align value-chain relationships to achieve greater efficiencies and performance improvements.

For NGOs that are reviewing the same macrodevelopments as business, a perceptible shift has evolved in the approach to working with government and business. Concerned about the large-scale effects of climate change, scarcities of natural resources and food, loss of biodiversity, and other planetary-scale effects, many of the leading NGOs have entered into more collaborative relationships with leading global companies. This process of dialogue has reached the point where they are developing common solutions and advocating similar agendas for resolving global, regional, national, and local issues. Beyond the collaboration with business, some NGOs have taken initiatives on various topics, such as developing global standards that would encourage the application of best practices to water management and water-quality protection. NGOs are also increasingly engaged with investors and the financial sector to alter methods of assessing effective governance, expanding transparency, and reconsidering valuations of capital and risk.7

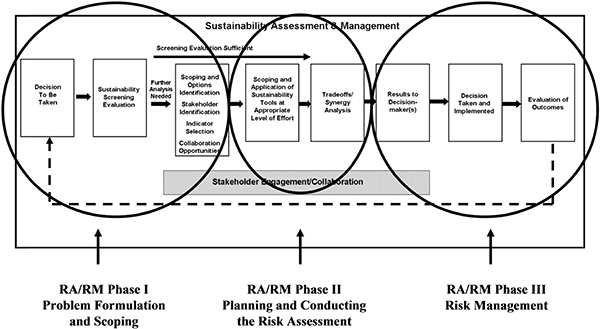

EPA has decades of experience in applying risk-assessment and risk-management decision tools to a variety of public-health and environmental challenges. As already noted in the present report, the agency has formalized the use of the tools in a formal decision-making framework that it periodically updates (EPA 2014d). In addition, the committee that prepared the Green Book (NRC 2011a) observed that its proposed Sustainability Assessment and Management (SAM) approach can include each of the basic elements of the risk-assessment and risk-management paradigms (see Figure 7-1).8 The Green Book recommended that EPA include risk assessment as a tool, when appropriate, as a key input into sustainability decision-making.

Risk-assessment and risk-management approaches are dynamic and are continually informed by new scientific information. A similar characteristic is present in sustainability tools and methods, such as LCA, benefit–cost analysis, megatrend analysis, and data analytics.

As discussed in Chapter 3, risk assessment can be used to inform considerations of sustainability concepts by estimating whether and to what extent public health and the environment will be affected if an action is taken. The present committee’s evaluation of how best to integrate risk assessment and other sustainability tools and methods is based on a consideration of four major factors:

____________________

7For an examination of recent coalitions between businesses and NGOs, see Grayson and Nelson 2013.

8In some cases, such as a short timeframe for a decision, the formal four-step risk assessment will not help to discriminate among potential decision options in a sustainability framework. For a decision process in which four-step risk assessment is included, the sustainability framework can be viewed as representing the risk paradigm expanded and adapted to address sustainability goals. See Chapter 5 of NRC 2011a.

• Planning and scoping that address all major sources of a problem. This would include not only the probabilistic evaluation of health and environmental effects associated with a specific pollutant or pollutant source (the most frequent application of risk assessment in EPA) but an examination of the economic activities in which the pollution originated (for example, the pollution-generating characteristics associated with the source of raw materials burned in a factory).

• Expanding the scope of problem formulation to include not only point and area sources that directly emit or contribute to pollution generation but energy and material flows throughout a value chain of activities that ultimately generate pollution further downstream. Transitioning from a “pollution source” to a “value chain” unit of problem formulation and analysis will provide EPA with important insights into how pollution is created and distributed.

• Many such innovations have emerged through the application of information technology that enables cost-effective analysis of individual problems and their linkage to interconnected systems of problems (for example, climate–water–food challenges) or the application of “traceability” methods that enable the tracking and tracing of pollutants or material flows among multiple participants in the economy (such as suppliers, manufacturers, distributors, and consumers). The application of those and other innovations has led to important insights for decision-makers in public, private, and nongovernment institutions and should be integrated into EPA’s decision-making frameworks.

• Using risk assessment and other sustainability tools that are “fit for purpose”. That term refers to the utility of an analytic tool that is best suited and adapted to support decision-making (EPA 2014d, p. xii). It applies equally to traditional risk assessment and sustainability methods.

EPA decision-makers need an expanded array of available tools to understand relevant trends emerging from the changing dynamics of the economy (locally, regionally, nationally, and globally). By integrating sustainability tools with an existing suite of risk-assessment methods, EPA would be better informed about the changing nature of risks that it is responsible for reducing and would have a system-level view of key interrelationships in economic–environmental–societal spheres of activities.

The committee agrees with the Green Book recommendation that EPA include risk assessment as a tool, when appropriate, as a key input into sustainability decision-making.

EPA should develop an integrated risk-assessment–sustainability analytic approach for decision-makers that can be applied as part of the SAM process throughout the agency’s programs. Such an approach should

- Identify the appropriate tools and methods for a variety of specific decision-making issues and scenarios.

- Articulate how particular sets of risk–sustainability tools and methods can be applied to specific sets of challenges within the scope of EPA’s decision-making responsibilities, such as regulatory, technical support and guidance, cross-media and cross-business sector, and international.

- Evaluate how EPA can apply risk–sustainability tools to specific value chains.

- Conduct a selected number of postdecision evaluations to determine the efficacy and effects of integrated risk–sustainability methods, assess how and whether they would have changed the outcomes achieved, identify risk tradeoffs, and identify new opportunities for solving sustainability challenges. (Recommendation 7g)

KEY CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

Conclusion 7.1: EPA’s various decision-making frameworks for the application of analytic tools and approaches function in parallel and are in various states of transition or development. Integrat-

ing the frameworks on the basis of sustainability concepts would enhance EPA’s decision-making to match the degree and scale of current and future challenges.

Recommendation 7.1: As EPA continues to evaluate and update its current decision-making tools and frameworks, it should strive to use sustainability concepts as an integrating principle for its strategic plan and implementation of its program responsibilities. The committee urges EPA to continue in its efforts to adopt or adapt the sustainability framework recommended in the Green Book (NRC 2011a). (See Recommendation 7a)

Conclusion 7.2: The application of sustainability tools and approaches to EPA’s day-to-day operations on a cross-program basis would enhance the agency’s execution of its existing activities.

Recommendation 7.2: EPA should embed the application of sustainability tools and approaches in its major activities in a manner that is consistent with its existing statutory authorities and programmatic experience:

- Evaluating existing regulatory policies for public-health and environmental protection and approaches to emerging challenges.

- Extending EPA’s role in data management and synthesis to aid the investment community, to fill information gaps in the commercial economy, and to monitor and identify problems and trends, many of which emerge in a nonregulatory context.

- Serving as a convener for collaboration in system-level solutions to leverage knowledge and problem-solving beyond the capability of any single institution or group, to foster cross-business sector collaboration and public–private partnerships, and to design system-level evaluation approaches throughout specific value chains.

- Developing approaches for cradle-to-cradle assessment of materials management, for evaluation of pollution-related risks and risk-reduction opportunities throughout an entire value chain and not only to individual sources or sectors, for integrated assessments of multiple individual risks that apply to cities, and for incorporation of resilience approaches. (See Recommendations 7b-7f)

Conclusion 7.3: Applying an expanded array of risk assessment and other sustainability tools and approaches would enhance EPA decision-makers’ understanding of the changing dynamics of the economy and risks associated with the changes.

Recommendation 7.3: EPA should develop an integrated sustainability and risk-assessment–risk-management approach for decision-makers. Such an integrated approach should include an updated set of appropriate tools and methods for specific issues and scenarios, examination of how EPA can apply risk assessment and other sustainability tools throughout specific value chains, and selected postdecision evaluations to identify lessons learned and new opportunities to inform future decision-making. (See Recommendation 7g)