2

Sustainability: From Ideas to Actions

Sustainability has evolved from an aspiration to a body of practices. The evolution includes a transition from the development of broad goals toward the implementation of specific policies and programs for achieving them and the use of indicators and metrics for measuring progress. A focus on the management of waste generated by societal activities and remediation of contaminated sites has broadened to include the use of new technologies and products that enable individuals and organizations to do more while creating less environmental impact. Businesses are coevolving collaborative and competitive strategies and initiatives that encourage innovation, regulatory change, and consumer choice in the pursuit of sustainability objectives. Individuals and organizations that are proponents of sustainability are more connected with other members of society through new social media that promote participation and transparency in the development and implementation of sustainability plans. Scientific endeavors are expanding from the study of single environmental media toward systems-focused, integrative research that deploys big-data capabilities and advanced analytics to assess effects over a broad range of considerations. Examples of results of sustainability initiatives include increased efficiencies in the use of energy and natural resources, the production of materials and goods that pose much less environmental hazard, and the construction of green buildings and communities.

That evolution is taking place against a backdrop of global forces and trends that are shaping how societies and the environment are interacting and changing. As those changes occur, institutional policies and approaches need to change in response. Societies are being challenged to move away from unsustainable practices toward ones that meet their needs while preserving or restoring the life-support systems of the planet (NRC 1999, 2011a).

In practice, sustainability initiatives explicitly strive to consider the broad assortment of factors and potential effects across an interlinked set of issues, both upstream and downstream of particular pollution sources, rather than focusing on potential health effects of particular environmental exposures. Sustainability approaches examine the sources of pollution and other challenges across entire value chains rather than focusing on individual point or area sources in specific economic sectors.

This chapter discusses various forces, trends, and considerations that are shaping sustainability concepts and sustainability practice. It also discusses Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) efforts to build consistency and continuity in the ways in which it incorporates sustainability concepts into its activities.

FACTORS THAT DRIVE THE NEED FOR SUSTAINABILITY TOOLS AND APPROACHES

Megatrends

Megatrends—including climate change, mega-urbanization, democratization of knowledge, and a renaissance in the development of industrial materials—present challenges to and opportunities for advancing sustainability initiatives.

Climate Change

Two recent scientific assessments find that climate change is already happening and that human activities—mostly related to energy and land use—are the primary cause of most of the change and that the resulting effects could undermine sustainability.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC 2014) finds that greenhouse-gas (GHG) emissions increased steadily on a global scale from 1970 to 2000 and then more steeply from 2000 to 2010—1.3% and then 2.2% per year. It also finds that achieving some measure of climate safety will involve a dramatic global increase in the use of low-carbon energy (to 3–4 times the share of low-carbon energy in 2010) and a dramatic global decrease in GHG emissions (by 40–70% from 2010 emission levels) by the middle of the 21st century. In addition, it notes that “adaptation and mitigation choices in the near-term will affect the risks of climate change throughout the 21st century” (IPCC 2014, p. 10).

The third National Climate Assessment produced in 2014 by the US Global Change Research Program finds that “global climate is changing and this is apparent across the United States in a wide range of observations” (Melillo et al. 2014, p. 15). The assessment confirms an increase in extreme weather and climate events and other effects, which can threaten human health and well-being, damage infrastructure, affect water quality and water-supply reliability, and disrupt agriculture and ecosystems.

Managing climate change is viewed as a challenge of managing risks. Societies need to make decisions (about both mitigation and adaptation) and take actions in the face of considerable uncertainty to address the extent and magnitude of climate change and the severity of its local and regional effects. The focus is becoming less on predicting climate and more on how societies can make themselves more resilient in the face of changes that can no longer be avoided. Mitigation and adaptation are seen as constituting a down payment on a sustainable future.

Mega-Urbanization

More than half the global population is urban, so cities constitute a dominant habitat for humans. The drive to urbanize is a transformative process that permeates many aspects of development as societies seek the services that urban centers provide. The services include transportation systems, which depend heavily on fossil fuels and are a major source of GHG emissions; buildings, which are often designed to over-rely on nonrenewable resources; and infrastructure (especially sewer systems, roads, and transmission lines), which was not designed to withstand hazards of climate change and other natural events. Also, in ethnically diverse urban areas, language barriers can isolate groups from official communication in advance of and in response to hazard events.

The demographic shift to urban areas is closely related to the large increase of the global middle class and its increasing purchasing power that, in turn, drives greater consumption of resources (Guarín and Knorring 2014). Increased population growth rates and demographic shifts present complex challenges. For instance, in the near future megacities will not only be required to support a growing and diverse population, but an increasingly aging one as well. This trend will present a substantial challenge to the ability of megacities to provide needed services to an increasingly aging population.

This economic shift is opening large new markets as regions that have historically exported raw materials are beginning to import products and develop their service economies to meet the demands of their growing middle class. As with any major transformation, the benefits will also come with some downsides. The increased mobility that comes from rising car ownership, for example, will put increased pressure on road infrastructure and likely will result in vehicle emission increases that degrade air quality. In addition, the growth of the global middle class suggests an increased demand for resources in global markets for oil, food, and minerals.

Cities can serve as crucibles for innovation and often are massive economic engines that can account for substantial improvements in the efficiency of activities, such as energy production and use, transportation, and health-care delivery. They present an opportunity to develop new sustainability metrics, tools,

and approaches that can be used to guide how cities are designed, built, and managed (NRC 1999). Urban areas also present an opportunity to increase understanding of human–environment interactions at the local level (NRC 2010). If increased urbanization is inevitable, it will be essential to find ways of making it more sustainable.

Democratization of Knowledge

Advances in electronic devices allow broad access to large amounts of information in a society. Such democratization of knowledge constitutes a dramatic change from the past. Coupled with the rapid expansion of computing capabilities, massive amounts of data enable highly advanced modeling and analysis that would have been unthinkable even 5 years ago and present new opportunities for sophisticated, evidence-based, and rapidly deployed sustainability assessments.

For example, high-performance computing has enabled the business, scientific, and regulatory communities to address a wide variety of complex problems in life sciences, health sciences, climate change, and many other spheres. The report Computing Research for Sustainability (NRC 2012a) describes the rich interplay between computing research and other disciplines in addressing the challenges of sustainability. The context provided by increased scientific and technical knowledge increases exponentially the value of the data collected. And high-performance computing and data analytics coupled with geographic information systems (GIS) leads to a growing ability to trace and track materials, supplies, and products around the globe with surprising accuracy and allows substantive improvements in documentation of the provenance of raw and processed materials. Such capability will be important in sustainability assessments in that it yields better data for sustainability tools and approaches, which in turn provide more accurate results.

Analysis of open-source data collected through social media can be a powerful tool in the execution of sustainability assessments. The value of social-media analytics lies in the opportunity to discover sentiments of millions of interested persons as expressed in on-line discussions and through direct solicitation of public comments. Powerful analytics make it possible to categorize and assess large numbers of public comments to obtain actionable insights and demonstrate responsiveness to public comment.

Materials Renaissance

New materials (such as graphene, quasicrystals, ceramics, shape memory alloys, nanomaterials, and thermoelectric materials) are being developed for industrial applications, such as enhanced production of transportation fuels, absorption of large volumes of oil from seawater by using porous nanostructructured fly ash, production of nanotransistors for microelectronic devices by using nanowires, repair of bones and teeth with biomaterials, treatment of drug-resistant bacterial infections with nanopolymer hydrogels, and purification of large quantities of freshwater at relatively low cost by using hybrid nanoscale materials. Such applications will present the challenge of understanding the potential unintended effects of the widespread use of the materials. A confounding issue associated in the development of a vast array of new materials is that they often become available for commercial use with little assessment of risks to the environment and health. For the promise of the materials to be realized, more purposeful assessments will be needed. It is unclear how many of the newly developed materials will lend themselves to the rapid screening assays developed for use in computational-toxicity assessments (EPA 2013b).

Public-Sector Policies and Initiatives

On an international level, the 2012 UN conference on sustainable development focused on pragmatic concerns related to sustainability, such as the green economy, green growth, and low-carbon development. The emphasis on building economic benefit from environmental protection reflected both the downturn of the global economy and the inevitability of climate change. Other international initiatives are

embracing sustainability in their missions, emphasizing results-oriented interventions that make use of new technology and tools, alternative forms of financing, business opportunities, and leadership. For example, the UN Greening the Blue initiative builds best practices in energy and environment into UN peacekeeping and other missions, and it uses social media to catalyze change and ensure accountability. The World Bank’s World Development Report (World Bank 2010) focuses on climate change and development and on the notion that a “climate-smart” world is within reach with targeted investments. At its 2014 meeting in Davos, Switzerland, the World Economic Forum devoted considerable time to high-level discussions of how to tackle climate change in the context of the global economic downturn.

In the United States, the Obama administration’s lead-by-example initiative places sustainability at the forefront of the federal government’s energy, water, and procurement targets. Executive Order 13514, Federal Leadership in Environmental, Energy, and Economic Performance, signed by the president in 2009, sets sustainability goals for federal agencies and focuses on improving environmental, energy, and economic performance. The order directs federal agencies to purchase sustainable products and services, improve efficiencies in water and energy use, and plan for climate adaptation (see Box 2-1). The potential effects of such practices on natural-resource consumption and on the kinds of materials flowing through supply chains are large because of the high volumes associated with the government’s procurement activity.

Federal-agency partnerships with communities can promote local sustainability initiatives. For example, the Sustainable Communities Regional Planning (SCRP) grant program, which the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) administers, supports locally led collaborative efforts among residents, municipal governments, and other interested parties with the goal of determining optimal ways to target housing, economic and workforce development, and infrastructure investment to create more jobs and regional economic activity. This is a key program of the Partnership for Sustainable Communities, in which HUD works with the Department of Transportation and EPA to coordinate and leverage programs and investment in federal housing, transportation, water, and other infrastructure entities to increase the prosperity of neighborhoods, provide accessible (available and affordable) transportation, and reduce pollution. The program has reached 74 regional grantees in 44 states and has assisted about 112 million people (HUD 2014).

Federal agencies are developing adaptation plans as part of the strategic planning recommended by the Interagency Task Force on Climate Change Adaptation and guided by Executive Order 13514. The plans consider the potential effects of climate change on government operations and the opportunities for adaptation in the context of effective natural-resource management. The president’s 2013 Climate Action Plan enhances federal support for adaptation through the creation of a task force, which was launched in November 2013 and is made up of state, local, and tribal government officials; it advises the federal government on climate-related issues that communities face in the hope that this will help in determining how the government can assist local communities.

Many local efforts are facilitated by nongovernment organizations—such as ICLEI [International Council for Local Environmental Initiatives] USA, which began in 1995 and now serves as a global network for local governments for sustainability initiatives—and by a burgeoning service industry in which a growing number of companies are developing frameworks that are intended to have wide appeal. For example, ICLEI's Sustainability Planning Toolkit, which is based on the model pioneered by city of New York's PlaNYC, provides guidance in developing a sustainability plan for improving the livability of cities, towns, and counties (ICLEI 2009).

The emphasis of those efforts is on deriving economic benefit from environmental protection and smart growth, building resilient communities, using new communication tools better so that plans can address the desires of individuals and communities, providing people with knowledge and resources needed to realize their goals, and spurring local innovation. In multiple studies, two-thirds or more of the US public supports taking sustainable actions and supports government efforts to promote sustainability initiatives (Cohen, et al. 2005; Leiserowitz et al. 2005; Morales 2010; Smart Growth America 2011; Greenberg et al. 2014).

In response to Executive Order 13514, EPA issued comprehensive procurement guidelines to promote the use of materials recovered from solid waste (also known as the buy-recycled program). EPA designates for purchase products that have high concentrations of recovered material. The agency also administers the Federal Green Challenge, which commits federal offices or facilities to an improvement goal of at least 5% per year in two of six target sectors: development waste, electronics, purchasing, energy, water, and transportation.

Leadership in Business and Industry

Perhaps the most rapid expansion of sustainability practice in the last decade has been in the private sector. Sustainability has become a greater business imperative, a source of competitive advantage, and an enabler of innovation. As described in Chapter 5, leading companies are seeking ways to lower their costs while building more efficient and sustainable operations, processes, products, and services. The focus of sustainability takes companies beyond mere compliance with government regulations to the creation of innovative products and services that give rise to new markets and revenue streams.

The Evolution of Sustainability Science

The scientific foundation and analytic tools used to support decisions in a sustainability context—regardless of whether the decisions are made by governments, businesses, nongovernment organizations, or individuals—will benefit greatly from new knowledge and better use of existing knowledge (NRC 1999; NRC 2011a). Such scientific capabilities as computational toxicology, remote sensing, and chemical screening are helping to build connections between the research domains of environmental sciences, economics, and sociology (Anastas 2012). Those advances are enhancing the development of sustainability science, a field of research recommended by the National Research Council report Our Common Journey: A Transition Toward Sustainability (NRC 1999) to address the special challenges of sustainability and sustainable development.

The Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America (PNAS) describes sustainability science as “an emerging field of research dealing with the interactions between natural and social systems, and with how those interactions affect the challenge of sustainability: meeting the needs of present and future generations while substantially reducing poverty and conserving the planet's life support systems” (PNAS 2014). It is defined by problems, not by disciplines (Clark 2007). Kates et al. (2001) presented a theoretical framework for sustainability science.

In a review of a large database of publications, Bettencourt and Kaur (2011) observed that sustainability science coalesced around the year 2000 as a result of collaborations among various disciplines throughout the world in several decades. The number of scientific publications increased at a rate of around 15–20% per year from 1997 to 2007 (Clark 2007). In 2005–2008, five new journals on sustainability science were launched. Several recent books and articles review the evolution of the field (Ness, 2013), showing its orientation toward action, integrated assessments, and interdisciplinary approaches (Spangenberg, 2011; de Vries, 2012); expansion and diversification (Komiyama et al., 2011); contribution to resolving problems of science and society (Wiek et al., 2012); and treatment of issues related to urbanization (Weinstein and Turner, 2012), planning (Hamdouch and Zuindeau, 2010), and energy (Kajikawa, et al 2014).

Networks have been developed for improving discussion between scientists and practitioners (Clark and Dickson 2003; NRC 2006) and for linking knowledge with action and supporting decisions (NRC 1999; NRC 2006; Cash et al. 2002; Cash et al. 2003). Recent areas of emphasis include addressing the need for better understanding of human behavior in response to environmental change, the resilience of complex and adaptive systems, better ways to disseminate relevant knowledge, and better models for de-

cision-support (Miller 2013; Miller et al. 2014) and ways of analyzing system components and their interrelationships (Liu et al., 2013).

Higher-education research centers, educational-degree programs, and interdisciplinary academic and research programs concerned with the environment and sustainability have grown considerably in the last several years (Ness 2013) and offer new partnership opportunities for EPA, business, and academic institutions. According to a 2013 survey by the National Council for Science and the Environment, there were 1,121 sustainability-science programs and centers in 236 universities; a 2012 census identified 1,151 academic units or programs that were offering 1,859 interdisciplinary environment and sustainability baccalaureate and graduate degrees in 838 colleges and universities (Vincent et al. 2013, p. 8). Those figures represents a 28% increase in the number of schools offering such programs and a 57% increase in the number of degree programs over a 4-year interval (Vincent et al. 2013). Such growth may be indicative of a shift in emphasis rather than of overall growth in education in the fields of science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (see Chapter 6).

Federal Science and Research Planning

In October 2010, the president’s National Science and Technology Council reconfigured its main committee on environmental R&D to encompass sustainability to form the Committee on Environment, Natural Resources, and Sustainability (CENRS) to develop a comprehensive R&D program among federal agencies; ensure strong linkages among science, policy, and management decisions; encourage the use of sustainability science; and promote innovation. Officials in EPA, the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy (OSTP), and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration serve as co-chairs of CENRS. In 2011, CENRS established a task force on Integration of Science and Technology for Sustainability, which includes EPA and 11 other federal departments and agencies, to define the research opportunities and needs in federal agencies. CENRS subcommittees, such as the Subcommittee on Global Change Research, are encouraged to develop their portfolios of programs with a view to sustainability outcomes.

The 2010 annual budget guidance memorandum to federal agencies from the directors of OSTP and the Office of Management and Budget identified science and technology for sustainability as having high priority for the FY 2012 budget, calling for “research on integrated ecosystem management approaches that bring together biological, physical, chemical, and human uses data into forecast models, assessments and decision support tools” that would address the presidential priority of “managing the competing demands on land, fresh water, and the oceans for the production of food, fiber, biofuels, and ecosystem services based on sustainability and biodiversity” (Orszag and Holdren 2010). Implementing those efforts requires interagency cooperation and joint programs, because no single agency has all the necessary expertise, data, or mandate to understand or mange the competing demands.

A 2103 National Research Council report, Sustainability for the Nation: Resource Connections and Governance Linkages, recommended that federal agencies supporting scientific research be given incentives to collaborate on sustained cross-agency research. The report also recommended that sustainability concepts be supported by a broader spectrum of federal agencies and that additional federal partners become engaged in science for sustainability (NRC 2013a).

SUSTAINABILITY IN THE ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION AGENCY

EPA’s mission is to protect public health and the environment. Societal needs, megatrends, market interactions, and advances in scientific understanding—described in this report—are driving the agency to incorporate sustainability concepts into its planning and activities. As noted in the Green Book, EPA’s mission is consistent with sustainability in that it fosters “human and environmental well-being at the same time for the benefit of present and future generations” (NRC 2011a, p. 9).

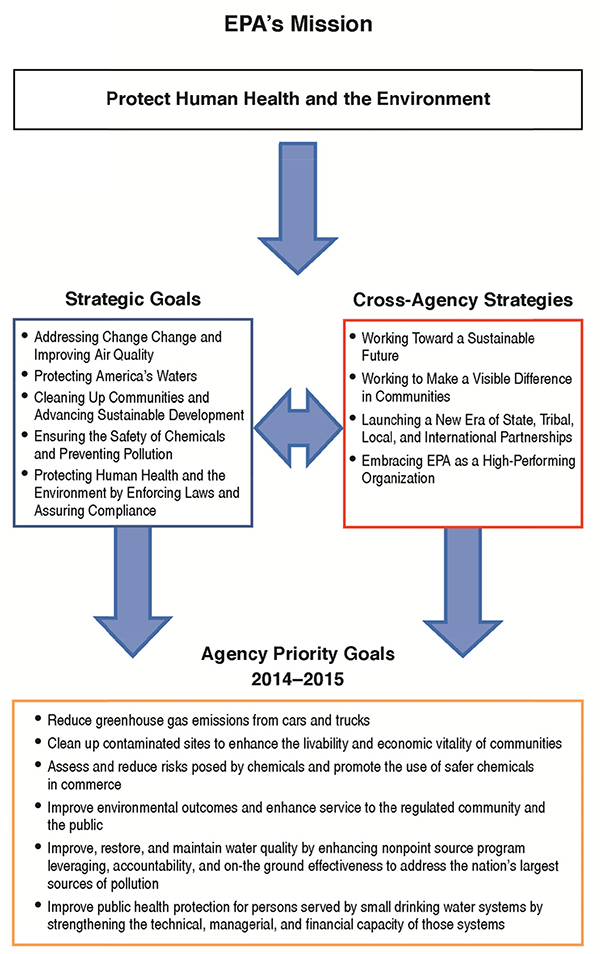

Figure 2-1 presents the agency’s overall strategic goals, cross-agency strategies (which include “working toward a sustainable future”), and the agency priority goals for 2014–2015. The priority goals reflect EPA’s present efforts to address climate change and improve air quality, improve water quality, promote green infrastructure development, reduce chemical risks, and enhance the livability and economic vitality of neighborhoods in and around waste sites (EPA 2014a). Sustainability can serve as an integrating decision framework covering all those priorities—not only as a way to think about problems but as a way to work toward their solutions across time horizons, geographic scales, and other considerations.

Four Priorities for Sustainability

In addition to establishing the goals and strategies mentioned above, EPA identified four priorities to advance sustainability (see Table 2-1). They were developed in recognition of legal constraints and of a desire to apply scientific tools and approaches in different circumstances and different modalities to move the sustainability agenda forward (Perciasepe 2013). With respect to the four priorities, EPA indicated (EPA 2014c, p. 1) that it will

• “Identify leveraging opportunities with communities, businesses, universities, and other stakeholders with which the agency is already working or should work to advance sustainability.

• “Identify opportunities to incorporate sustainability principles into regulatory, enforcement, incentive-based, and partnership programs.

• “Design a targeted strategy including identifying appropriate goals to advance the four areas.

• “Identify process and lessons learned through the four areas to be applied to other areas.” (EPA 2014b, p. 1)

EPA’s four priorities for sustainability provide a good beginning for establishing comprehensive, cross-medium activities. It is not peculiar to EPA that consideration of the environment pillar of sustainability has dominated, but many of the trends noted previously in this chapter reinforce the need to improve understanding of other aspects of human well-being—the social and economic pillars.

Incorporating Sustainability Considerations in All Activities of the Environmental Protection Agency

EPA’s mission provides ample opportunities for incorporating sustainability into the broad array of the agency’s activities (see Table 2-2). EPA’s activities are in two general categories: required activities driven by congressional mandates or administration directives, such as executive orders, and voluntary or discretionary activities driven by agency policy priorities that are consistent with its statutory responsibilities for advancing the application of innovative methods and best practices related to a variety of public-health and environmental challenges. EPA’s required activities (such as regulatory development and enforcement) stem from mandates and directives that tend to be related to specific environmental media (air, water, and land), pollutants (particular chemicals), responses (such as oil spills), issues (such as endangered species), or demographic groups (such as children). Voluntary activities afford greater flexibility for incorporating sustainability. Table 2-3 provides several examples.

Taken together, EPA’s required, voluntary, and discretionary activities are wide in scope and scale and thus present the agency with considerable opportunities to incorporate sustainability considerations at multiple levels of activity (see Box 2-2). Even regulatory actions involve decisions that can begin to incorporate sustainability concepts through screening evaluations, problem scoping, or identification of alternative actions to be considered. For each activity presented in Table 2-2, several general questions can help to integrate sustainability thinking:

• How does the activity expand the scope from the environmental pillar to address the social and economic pillars?

• What sustainability-related outcomes does the agency seek to achieve for a particular activity? How does the activity advance the outcome?

• What tools and approaches could the agency use to achieve the desired outcomes?

• What types of processes or partnerships with industry, nongovernment organizations, or academe will mobilize action?

TABLE 2-1 EPA Sustainability Priorities (FY 2014)a

| Priority | Initial Focus |

| Sustainable products and purchasing | Multistakeholder systems to define and rate sustainable products and purchasing |

| Green infrastructure | Storm-water management |

| Sustainable materials management | Food |

| Energy efficiency | Measures to enhance electricity-system efficiency that can support the president's Climate Action Plan |

aThe priority areas are the ones provided by EPA (Trovato and Shaw 2013). The priority areas are also discussed in Working Toward a Sustainable Future: FY 2014 Annual Action Plan (EPA 2014b).

TABLE 2-2 Some Potential Opportunities for Incorporating Sustainability Concepts into EPA Activities

| EPA Activity | Potential Opportunity for Incorporating Sustainability Concepts |

| Program development | Responding to emerging issues and setting priorities when resources are limited |

| Internal guidance | Advising on the application of tools and approaches, such as risk assessment, benefit–cost assessment, life-cycle assessment, social cost of carbon analysis, ecosystem-services valuation, and systems analysis for sustainability |

| Research planning and cross-cutting strategies | Using workshops and other techniques to encourage an integrated, science-based process throughout the agency |

| Budget decisions | Using a sustainability perspective for planning and allocating funds in all types of activities |

| Regulatory and standards development | Conducting regulatory impact analyses that use sustainability approaches |

| Regulatory enforcement | Including consideration of best practices in reducing chemical releases into the environment and a broad array of expected impacts, including value-chain impacts |

| Knowledge transfer | Providing information on tools for remediation that advance sustainability outcomes |

| Permitting | Advising states, other federal agencies, and EPA regions on the preparation of environmental-impact statements that incorporate sustainability criteria |

| Superfund | Including in the process for arriving at a record of decision the broad consideration of possible effects of remediation alternatives and the potential for natural systems to advance remediation |

| General communication and education | Compiling a compendium of lessons learned by incorporating sustainability concepts into activities and disseminating best practices through communication, education, and other activities |

| Stakeholder, community, and congressional relations | Including explanations of sustainability concepts and tools used to incorporate them into specific EPA activities |

| State and tribe collaborations and assistance | Using interactions to test the application of innovative sustainability approaches |

TABLE 2-3 Examples of Voluntary Programs in EPA to Advance Sustainability

| Program or Type of Activity | Objective |

| Design for Environmenta | Evaluate human health and environmental concerns associated with chemicals and industrial processes. Inform the selection of safer chemicals and technologies. |

| Green chemistryb | Design chemical products and processes that reduce or eliminate the generation of hazardous substances. |

| ENERGY STARc | Support the deployment of energy-efficient products, practices, and services. |

| Sustainable Water Leadership Programd | Recognize water and wastewater utilities that demonstrate sustainable management approaches for promoting resource efficiency and protection. |

| People, Prosperity and the Planet Student Design Competition for Sustainability (P3)e | College competition for designing projects to advance sustainability—water, energy, agriculture, built environment, materials and chemicals, cookstoves, and green infrastructure. |

aEPA (2014c).

bEPA (2014d).

cEPA (2014e).

dEPA (2013c).

eEPA (2014f).

Successful integration of multiple sustainability factors relies on

• Systems thinking and integrated approaches that address the connected aspects of multiple stresses or problems rather than focusing exclusively on solutions to individual problems.

• Decision-making that reflects the state of sustainability science, innovation, and knowledge about environmental, social, and economic consequences, alternatives, and tradeoffs.

• A sustainability framework, tools, and approaches for guiding actions.

• A process that asks initially what communities care about, identifies options, and uses relevant knowledge to identify sustainability indicators and metrics, select analytic tools to assess the options, and assess the outcomes.

• Management that is adaptive and flexible in addressing sustainability objectives among value chains, geographic regions, and time horizons; pursues collaborations and partnerships; seeks to be transparent and accountable in a more connected society; and ensures that decisions are achieving objectives.

Research and Development in the Environmental Protection Agency for Sustainability Science

In 2011, EPA began to reorganize its research programs to be as responsive as possible to the agency’s science-priority needs and to advance sustainability science (see Box 2-3) (EPA 2012a). Early impetus for the realignment was provided by EPA’s development of a sustainability research strategy in a systems-based multimedia context (EPA 2007). More recent motivations were provided by the Green Book (NRC 2011a) and guidance from EPA’s Science Advisory Board (EPASAB 2010). The reorganization is intended to link the traditional regulatory program offices (air, water, and chemical safety) with broader sustainability-related concerns.

EPA’s response to the Green Book recommendations also includes building capabilities needed to apply the sustainability assessment and management approach (see Chapter 1) by gathering analytic tools and approaches and indicators and metrics for sustainability assessment and management. For example, through the Sustainable Futures Initiative, EPA worked with industry and nongovernment organizations to develop computer-based models for industry to use in identifying risky chemicals in the early stages of development and in finding safer substitutes or processes before chemicals are submitted to EPA for approval (see also the case study on Design for the Environment in Chapter 4) (EPA 2012b)

In addition, EPA issued A Framework for Sustainability Indicators at EPA (EPA 2012c), which provides methods and guidance to support the application of sustainability indicators in EPA decision-making. Indicators are measurements that provide quantitative information on important environmental, social, and economic trends. The indicators presented in that EPA report are intended to be consistent with and augment the indicators in EPA’s Report on the Environment (EPA 2014g),1 which provides information on national conditions and trends in air, water, land, human health, and ecologic systems.

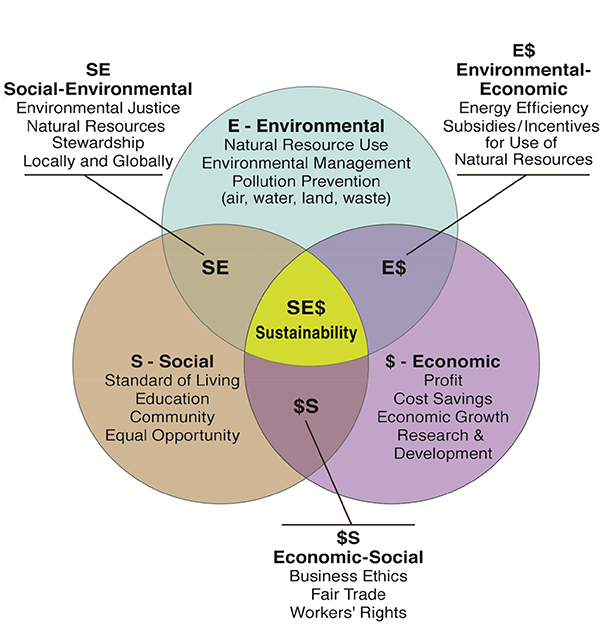

As shown in Figure 2-2, individual indicators can be relevant to one or more of the sustainability pillars. For example, the amount of fossil fuel consumed to produce energy for residential use is a sustainability indicator in the environmental pillar (region E in the figure). A more integrated indicator is change in the energy efficiency of residential heating and cooling equipment (region E$ in the figure) because energy efficiency is relevant to fossil-fuel use and cost savings. An example of a single indicator that is relevant to all three pillars (region SE$ in the figure) is per capita floor space of residential dwellings. Because the indicator correlates with energy consumption and economic status, it reflects aspects of financial prosperity, quality of life, and resource use (EPA 2012c).

____________________

1The Report on the Environment is a compilation of scientific indicators that describes the condition of and trends in US environmental and human health. The new version of the report is entirely Internet-based.

EPA has been involved in developing integrated indicators, such as environmental burden (ecologic-footprint analysis), flow and conservation of energy resources (energy budget), and regional economic health (Green Net Regional Product) (Campbell and Garmestani 2012; Gonzalez-Mejia et al. 2012; Heberling et al. 2012; and Hopton and White 2012).

BOX 2-2 EPA Activities in the Gulf of Mexico

As a first responder to environmental hazards, EPA was called on to make decisions about the use of chemical dispersants during the Deepwater Horizon oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico in 2010. EPA also chaired the Gulf of Mexico Restoration Task Force established in 2010, because it is the lead agency in restoring degraded environments and developing long-term programs for protecting the environment and human health. EPA was also a participant in the National Ocean Council, which was established coincidentally in the aftermath of the Deepwater Horizon oil spill to coordinate marine spatial planning for multiple human uses of near-shore marine areas, including the Gulf of Mexico.

The decision to use dispersant chemicals to promote the breakup of spilled oil into smaller droplets in the water before it could reach wetlands and the shoreline had implications for the locations and priorities for restoration in the near term and for sustainability considerations in the long term. The considerations include fate and effects of the dispersed oil, toxicity of the dispersant chemicals, and the health and economic well-being of gulf-states residents. Decisions at multiple levels need to consider the implications of system dynamics and environmental, social, and economic factors.

FIGURE 2-2 Three sustainability pillars, showing various indicators in their relevant domains. Some indicators are relevant to only one domain, and others are appropriate to more than one. Source: EPA 2012c, p. 7.

BOX 2-3 Research Programs of EPA’s Office of Research and Development

Air, Climate, and Energy: Exploring the dynamics of air quality, global climate change, and energy as a set of complex and interrelated challenges.

Chemical Safety for Sustainability: Investigating ways of producing chemicals in safer ways and embracing principles of green chemistry.

Homeland Security Research: Protecting human health and the environment from the effects of terrorist attacks or accidental releases.

Human Health Risk Analysis: Understanding effects of pollutant exposure on biologic, chemical, and physical processes that affect human health.

Sustainable and Healthy Communities: Building a deeper understanding of the balance between the three pillars of sustainability.

Safe and Sustainable Water Resources: Maintaining drinking-water sources and systems and protecting water integrity.

After the Green Book was issued, EPA also prepared a report Sustainability Analytics: Assessment Tools and Approaches, which provides examples of science-based tools and approaches for conducting sustainability assessments once indicators are selected and corresponding metrics are identified (EPA 2013a). It is not intended to set policy or prescribe a process for implementing sustainability analytics. As discussed in Chapter 3, the committee used that EPA report as one of its bases for identifying the tools and approaches that it would consider in carrying out its study.