The National Research Council and other entities have previously studied components of the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) laboratory enterprise. Their studies have resulted in a number of important recommendations to increase the efficiency and effectiveness of EPA’s research capabilities. The focus of those studies and recommendations has been, for the most part, on the Office of Research and Development (ORD) laboratories. EPA has generally been responsive to the recommendations and has improved the management of ORD. One example is the Pathfinder Innovation Project, an internal competition to engage workers with release time to generate new ideas of high benefit and high leverage. Another example is the designation of national program directors to improve alignment of the work of ORD laboratories with program office needs.1 (See Appendix D for a list of recommendations provided in previous reports.)

As discussed in previous chapters, however, ORD is only one component, albeit an important one, of the laboratory enterprise. More important for present purposes, the other components—the regional office laboratories and program office laboratories—are not mini-ORD laboratories. They generally do different types of work; ORD focuses more on basic and applied research whereas program office laboratories and regional office laboratories focus more on technical support and analytic services. The various components typically work on different timeframes; ORD may undertake research with a 5-year view whereas a regional office laboratory might need an answer for a cleanup facility extremely quickly and a program office laboratory may be engaged in technical projects that span a couple of years. As a result of their different tasks, the various laboratories need different types of scientific and technical expertise, and the various components report to different managers and policy officials—ORD laboratories report to the ORD assistant administrator, each regional office laboratory reports to its regional administrator, and each program office laboratory reports through its program office to its program office assistant administrator.

One consequence of those differences is that the previous recommendations for the ORD laboratories cannot simply be applied to the laboratory enterprise as a whole. Of greater importance is the fact that the “enterprise as a whole” consists of diverse types of entities that have different immediate priorities, are typically in different places, and are required to do different things. EPA’s laboratory enterprise thus presents a management challenge. A cohesive entity with roughly comparable components near one another is one thing; EPA’s laboratory enterprise, which is operated as a distributed network of laboratory facilities, is quite another. There are, to be sure, institutional links and substantial interactions among the various components of the enterprise, but, except for the concept, there appears to be little substance to the notion of a laboratory enterprise as a single entity. Indeed, the committee’s requests for information and questions presented to EPA about its laboratory enterprise generally produced responses that focused on specific types of laboratories. The impression conveyed was that the laboratory enterprise consists of many different components, not a single functioning cohesive entity.

_________________________

1Each of ORD’s six national research programs is led by a national program director. The directors are responsible for ensuring that the science conducted is relevant and of high quality (EPA 2014c).

It is not within the committee’s statement of task to recommend reorganization or a consolidation of components of the enterprise. We do, however, recommend a reorientation and synchronization of the enterprise. Specifically, as discussed below, EPA should approach management of its laboratory enterprise not so much as separate types of laboratories but as a system of the various laboratory efforts in EPA in which science and technical support activities are undertaken to support and advance the agency’s mission–in other words, as an organized composition of diverse components. (Recommendation 4-1)

We discuss here first the need for a clear vision for the laboratory enterprise in accordance with summary principle 1: Every science institution is more effective if it has a vision of how its scientists, technicians, and other professionals can best contribute to the organization’s mission and goals. Next, we address the management processes that would help to tie the enterprise together, focusing on planning and budgeting, implementation and allocation of resources, assessment, and communication within EPA. The chapter also provides the figures presented in Chapter 2 with additional questions (criteria) to illustrate kinds of information needed by the different types of labs to enhance effectiveness and efficiency at the enterprise level. The questions serve as an overview of the areas of improvement discussed in the chapter.

An important part of management is knowing what the entity is and what it is intended to do, and this is true of every scientific institution as well. (Principle 4-1) As noted above, the laboratory enterprise is currently more of a conglomeration than an organization. The amorphous nature of the enterprise is made all the more difficult for outsiders to grasp because the laboratories (be they ORD laboratories or regional office laboratories or program office laboratories) are only a part of the many and varied scientific efforts within and external to EPA that support its mission. Scientists, technicians, and engineers play important roles in the Office of the Administrator, in the program offices, and in the regional offices apart from the varied laboratories. That is all supplemented or complemented by the broad university research community around the country; by scientific research sponsored by many other parts of the federal government, its laboratories, and its research centers; by state agency laboratories; and by the private sector. As we discuss below, all those components (and the connections forged between them) contribute to EPA’s ability to carry out its regulatory responsibilities on a day-to-day basis and to generate frontier knowledge that will contribute to fulfilling the EPA mission and to its future accomplishments.

The 2012 National Research Council report Science for Environmental Protection: The Road Ahead captured the role of science in EPA for the agency as a whole but did not single out the role of the laboratory enterprise in that effort. On the basis of our examination and review, we have concluded that EPA does not have a comprehensive justification or organizing vision for its current laboratory enterprise. For example, the EPA Web site includes a historical perspective: “Why Are Our Regional Offices and Laboratories Located Where They Are?” was written by Assistant EPA Historian Dennis Williams in 1993 in response to a request from the director of the EPA Office of Administration, John Chamberlin. The history (Williams 1993) concludes, “Since the early 1970s, some facilities have been closed and a few new ones have been opened, but the Laboratory system remains a product of the practical solutions developed by agency officials in the early 1970s to the problem of how to best use the facilities it inherited in December 1970.” Today there may be sufficient reasons for the locations of most of the EPA laboratories. Some of those reasons are in part historical, others may have to do with the needs and priorities of the regions and the laboratories that support them, and still others may have to do with the needs and priorities of the programs.

We have not been tasked with sorting out the reasons for the locations of the laboratories or with recommending changes or consolidations. EPA has made substantial changes in its laboratory enterprise in the last decade and is examining ways to improve the efficiency and effectiveness of the enterprise further. In the process, EPA will probably consider such questions as these:

• Why is the laboratory enterprise structured (or not structured) as it is?

• Why do the components of the laboratory enterprise undertake the work they do?

• Most important, “how do the various elements of the EPA laboratory enterprise work together to achieve EPA’s missions most effectively?

In light of those questions and related consolidation options, the committee notes that EPA laboratories in some parts of the country often support EPA missions in other parts of the country. EPA has several nationally and internationally well-regarded large fixed, laboratory facilities that would be expensive to move,2 but EPA is generally noted for the scientific and technical expertise of its people, wherever they are. Accordingly, EPA can consider its laboratory enterprise primarily from the point of view of its capability to fulfill EPA missions overall.

Another important part of this process will be to articulate a vision for the EPA laboratory enterprise. That vision should strive to answer Director Chamberlin’s question anew and address not only why the laboratories are where they are but how the various elements of the EPA laboratory enterprise work together to achieve EPA’s missions. A vision for EPA’s scientific endeavors will help EPA scientists, engineers, and technicians to see where they fit in, help the overall laboratory structure operate more effectively, and help to avoid unproductive efforts. As indicated in the summary principles presented in Chapter 3, every science institution is more effective if it has a vision of how its scientists, and technicians, and other professionals can best contribute to the organization’s mission and goals. The EPA laboratory enterprise underpins the role of the agency as regulator, as setter of standards, and as a center of research related to its mission. It is wide-ranging and requires the insight of many scientific disciplines. We revisit those issues below. In any event, EPA should develop a vision for its laboratory enterprise that maintains the strengths of the individual components but provides synergy through systematic collaboration and communication throughout the agency. (Recommendation 4-2)

If EPA were to think of the laboratory enterprise as a system consisting of several different components organized to advance the mission of the agency, then there are a variety of management processes that could be strengthened to tie the components together without sacrificing the decided advantages that come from the in-depth experience, strong relationships, and proximity that has been the hallmark of the research, program office, and regional office laboratories. To better develop the effective and flexible management called for in summary principle 6, we look specifically at planning and budgeting, implementation and allocation of resources, assessment processes and, perhaps the most important, communications (summary principle 7).

Planning and Budgeting

As discussed below, EPA now uses a relatively well-developed strategic planning process; this extends to the separate components of the laboratory enterprise but not to the enterprise as a whole. Budgeting generally tracks the planning process for the agency and does not provide all the information that would be helpful in enhancing the efficiency and effectiveness of the laboratory enterprise.

_________________________

2For example, the National Vehicle and Fuel Emissions Laboratory, in Ann Arbor, MI, is the primary EPA research laboratory used for fuel and emission testing. Its work supports the Office of Air and Radiation’s efforts to establish and enforce emission standards for motor vehicles, engines, and fuels and to develop automotive technology (EPA 2013a).

Planning

On the basis of information provided by EPA, we understand that each ORD national program director, “building upon feedback received from ORD partners during the previous planning cycle, and the identification of new and emerging issues identified by the Laboratories and Centers, conducts a Portfolio Review” in the winter or spring of each year (EPA 2014j).3 Thereafter, each research program conducts a program update with the appropriate program and regional offices.4 In the July and August timeframe, further high-level discussions take place among officials of ORD, the program offices, and the regional offices to update the status of ORD research related to their programs, to confirm the research needs of the partners, and to receive approval for changes in research direction. In later summer and early September, ORD senior managers meet with the regional administrators and assistant administrators involved in each national program area to discuss the preceding year’s accomplishments and priorities for the future. The information gathered through this process is formalized within the ORD research-management system, a database that contains a comprehensive view of ORD’s current and planned research, which is used internally by ORD management and staff and can be accessed by program and regional offices throughout the agency.

The committee commends EPA for its progress in aligning the research efforts of the agency with the needs of its program and regional offices and ultimately with its strategic goals. However, more probably can and should be done. The materials that we have reviewed suggest that ORD, which has been through the most extensive external reviews, has implemented many of the reviewers’ recommendations (see Appendix D), with the result that it appears to have a solid planning process. The committee strongly supports ORD’s efforts to engage the program and regional offices as part of its annual planning process. We assume that the program office laboratories provide input to the program offices and the regional office laboratories provide input to the regional offices for the planning process. But the committee (and presumably other outsiders) does not know the extent of such involvement or whether it is ad hoc or systematic, because this part of the planning process is not transparent.5 In addition, we commend Region 6 for its performance during the gulf spill and Region 2 in the New York City polychlorinated biphenyls schools crisis, but we have not seen how the experience of those emergencies or of other unexpected situations factors into the present year’s or future years’ planning.

Another gap that may exist (again, the committee does not know) is in the extent of consultation and coordination among the various regional office laboratories or program office laboratories for their own planning purposes. Many of the regional office laboratories undertake the same or similar activities. Although there are venues for consultation among them, such as annual meetings of the regional office laboratory directors, the committee was not able to assess the level of coordination flowing from them, including measures to improve the efficiency and effectiveness of the regional office laboratories as a group.

Systematic involvement of all the agency’s laboratories in the planning process is far preferable to ad hoc connections and would probably yield a stronger and more efficient laboratory enterprise. (Princi-

_________________________

3The purposes of the portfolio review, in which both the management and research staff of the laboratories and centers participate, are to review the status and progress of research projects and tasks, to highlight issues that affect completion or timeliness, to review ending tasks, and to discuss potential new projects or tasks with EPA partners and stakeholders.

4These updates occur at the staff level and include a review of and discussion about the status of products, discussion of issues or changes in research directions, documentation of partner comments on previously delivered products, and identification of new or emerging partner needs.

5The committee also does not know the extent to which the program office and regional office laboratories have input into the planning processes of their chains of command whereby any new needs of the program offices or regional offices are filtered down to the work plans of the laboratories or how elimination of a laboratory-related function is communicated to the laboratories and implemented by them. In fact, what we have been provided suggests an expectation in both the program office and regional office laboratories that business will proceed as it has in prior years.

ple 4-2) At the very least, it would bring into the planning process each of the various contributors to the end result, so they would be cognizant of how their efforts lay the foundation for or build on work done by others to achieve the optimal performance of the agency in moving toward its strategic goals.6 And systematic involvement of the laboratories in the planning process would make it evident to EPA senior managers where there may be duplicative or overlapping resources that can be eliminated or redirected to other, more pressing needs of EPA. EPA should ensure that its laboratory planning process includes cross–regional office and cross–program office laboratory input and that it is more transparent within the agency and to outsiders. (Recommendation 4-3)

Budgeting

In moving toward more efficient and effective management of its laboratory enterprise, EPA may be hampered by a lack of critical information related to its laboratories. Specifically, during the committee’s deliberations, it was difficult to get a handle on the amount of funds attributable to the laboratory enterprise. There is a line item in the agency’s budget for science and technology, which includes costs (primarily salaries) for scientists, and so on, for laboratory scientists and those working in nonlaboratory settings (such as risk assessors), and there is another line item for capital expenditures that includes the laboratories’ capital equipment and other capital needs of the agency. But there is not a line item in the agency’s budget for just the laboratory enterprise. The funds for the ORD laboratories can be identified in the budget, funding for the program office laboratories can be extracted from the program offices’ budgets, and funding for the regional office laboratories can be extracted from the regional offices’ budgets. But it appears that EPA does not routinely add all the numbers together to produce a laboratory enterprise budget.7

That may be a function of the fact, noted above, that EPA has traditionally viewed the laboratory enterprise as many components, not as a single cohesive enterprise. In that light, it may not have been thought important for EPA to know how much was actually budgeted for the laboratory enterprise or for each of the individual laboratories, wherever they are on an organization chart.8 If there were a reorientation that would bring EPA to view the laboratory enterprise as a coherent system of various components operating together at some level, such information would be valuable in enabling EPA to manage that entity.

Some of this information may become available from the EPA’s current facility-level analysis (see Chapter 1). EPA itself can undoubtedly generate other data internally. Having such data would enable EPA not only to ensure that its available resources are being allocated to projects of the highest priority for the agency but to make comparisons among similarly situated laboratories and to have a benchmark for contract laboratories or university researchers when it chooses to outsource some of it work. It would also enable EPA to determine more easily the marginal cost of new laboratory capacity, equipment, or capabilities. And it would enable EPA to determine more easily whether its budget provides for long-term laboratory needs, especially whether there is room in the budget for emerging issues. It is often said that what gets measured gets managed. Equally important, it would enable outsiders to understand and evaluate EPA’s choices better. Indeed, as resources become even more constrained and the scientific issues

_________________________

6Personnel in the program office and regional office laboratories have the best insight into what is happening on the ground (for example, the compliance issue in the regions) or into the tricky questions in drafting regulations or standards (for example, measurement issues in the program office laboratories). Such insight would be valuable for planning purposes as well as for operational issues.

7In presentations to the committee, EPA representatives continually stressed that the laboratories do not receive budgets but rather that ORD, the programs, and the regions receive budgets and these entities, depending on their specific priorities, provide funding to their associated laboratories to support projects that ORD, the programs, and the regions have attached priorities to.

8This may have been accepted practice because the Office of Management and Budget does not usually ask agencies to provide budget information below the program or project level.

related to the environment become more complex and demanding, it may well be critical for EPA to have these types of data so that it can defend its need for resources or increased resources for the laboratories to carry out their functions.

EPA’s staff and leaders may be reluctant to break out laboratory costs. For example, it might make some activities vulnerable to being eliminated by the Office of Management and Budget or Congress in its attempt to delete items that are expensive or controversial. However, it is just as likely that if EPA has reliable data to support its research, it will be able to withstand many such pressures. Accordingly, EPA should conduct an annual internal accounting of the cost of the entire laboratory enterprise as a basis for assessing efficiency and assisting in planning. (Recommendation 4-4)

Implementation and Allocation

The Committee did not have the time or the resources to begin to answer several questions regarding implementation, including this one: Are there sufficient people, facilities, equipment and instrumentation, and funds to carry out the annual work plan? However, the committee identified two ways in which we believe greater use of traditional management processes could be used to strengthen EPA’s laboratory enterprise. The first is related to developing or capitalizing on assets (especially people) that can be used to respond to or resolve common problems throughout the laboratory enterprise, and the second is related to enhancing the likelihood that funding for work in the laboratory enterprise is directed to the agency’s highest priorities.

Personnel Deployment

Once a research project has begun, there may be discussion or collaboration among scientists, technicians, and engineers throughout the laboratory enterprise—indeed, throughout the agency—and with colleagues in other parts of the federal government; in state, local, or tribal agencies; in the private sector; or even in international agencies.9 As with planning, however, such cross-fertilization appears to be ad hoc rather than the result of any systematic process.

The committee was nonetheless encouraged by briefings on two undertakings that capture the essence (in different ways) of an approach that would use the expertise, talents, and general capabilities of all its laboratories personnel more efficiently. The first is the National Center for Computational Toxicology (NCCT). The NCCT is a relatively small ORD center, founded in 2005, that has 15 federal full-time-equivalent personnel, 30 research fellows and contractors, and a budget of about $7 million in FY2013. The mission of the center is “to integrate modern computing and information technology with molecular biology to improve Agency prioritization of data requirements and risk assessment of chemicals” (Kavlock 2009). Although it is an ORD center, its expertise can be deployed to assist all the EPA laboratories—ORD, regional office, and program office laboratories—when confronted with issues that would benefit from these specialized skills and thereby eliminate the need to replicate this type of service in different laboratories in the laboratory enterprise.10

A second undertaking is that of the Emergency Response Laboratory Network (ERLN) mentioned in Chapter 1 and the National Homeland Security Research Center. The center’s mission is to “conduct re-

_________________________

9Examples include the development and validation of methods to assess the exposure of honey bees to agricultural pesticides. In this instance, Office of Chemical Safety and Pollution Prevention laboratories worked with the Office of Pesticide Programs Environmental Fate and Effects Division.

10A program office laboratory that has a similar cross-EPA role is the National Analytical Radiation Environmental Laboratory (NAREL), whose missions are sample analysis, technical assistance, and guidance related to radiation. “NAREL is EPA’s only radiation laboratory and provides analytical support and technical Assistance to ORIA [Office of Radiation and Indoor Air], the EPA regions, other EPA offices, and other federal agencies and states” (Griggs 2013). EPA also defines NAREL as the National Air and Radiation Environmental Laboratory.

search and develop scientific products that improve the capability of the Agency to carry out its homeland security responsibilities”;11 it is primarily in and staffed by ORD’s Cincinnati facilities and is a major contributor to the ERLN. Unlike those in NCCT, ERLN participants are not colocated but rather work from 148 federal, state, and commercial locations and form a virtual analytic network, maintaining their day jobs but linked for rapid responses for issues that they are prepared to deal with.12

Both those models (and others are available) pool or draw from the skills, expertise, and experience of the scientists, technicians, and engineers that work in the various components of the laboratory enterprise. The committee commends EPA for developing these variations of entities within the laboratory enterprise and encourages it not only to continue its support of these and similar entities but to look for other opportunities in which different laboratories might encounter the same or similar problems, issues, or obstacles and a centralized resource—real or virtual—can assist in their resolution. In short, EPA should continue to look for innovative ways to address emerging problems and opportunities that create synergies among agency personnel who might encounter similar problems or opportunities within different EPA laboratories within ORD, program offices, and regional offices. (Recommendation 4-5)

Funding Allocations

The previous discussion was focused on pooling resources, but another process whereby the laboratory enterprise can be strengthened involves the allocation of common resources (the funding authorized by Congress) to the various laboratory activities in a way that is aimed at the strategic goals of the agency. During our information-gathering sessions, EPA representatives continually stressed that the laboratories are not allocated funds from a single source. Instead, the program offices, the regional offices, and ORD receive budgets, and these entities, depending on their own priorities, provide funding to their associated laboratories to support projects to which the programs, regions, or ORD have assigned high priority.13 We are not aware of any important shortfalls or lapses in laboratory-related activities with this approach, but it is troublesome that there is no process whereby the entire portfolio of laboratory projects can be arrayed to enable an evaluation of whether available funds are being allocated to activities so as to align best with the agency’s mission. Moreover, if resources are constrained further, as they might well be, there is no systematic way to ensure that the funds will be directed to the projects of highest priority to the agency.

Earlier in this chapter, when we discussed the potential benefits of having more robust budget information for the planning process, we focused on the costs of individual laboratories. This section goes one step further to recommend that EPA compile adequate data regarding the costs of individual activities in the various laboratories so that it can manage the laboratory enterprise appropriately. (Recommendation 4-6)

It is not clear from the information that we received from EPA how the various laboratories determine how much a specific laboratory project will cost when they provide an estimate for budgeting and planning purposes or whether any specific cost accounting is maintained by a given laboratory in implementing a project—be it a short turn-around project conducted by a regional office laboratory or a multiyear scientific research project undertaken by an ORD laboratory—so that it can monitor costs during the life cycle of an activity and refine budgeting procedures. The overall aim should be for EPA to have the ability to produce fairly accurate estimates of costs for implementing various types of laboratory activities

_________________________

11The center was charged by presidential directive for EPA to be the lead agency in coordinating protection of the nation’s water infrastructure and efforts to decontaminate outdoor and indoor environments.

12The center does have a core staff of 48 people but can scale up to meet needs.

13In ORD, each national program director receives a research budget through a process of setting priorities for specific research projects that have been identified as part of the annual strategic planning process. The program directors then go to the ORD laboratories and ask what part of the high-priority items can be done with the available funds.

before undertaking a project and be able to provide final costs at the completion of the project.14 (Principle 4-3) EPA can use such data to compare the costs of similar projects in different laboratories,15 to benchmark for any outsourcing that may be contemplated for similar projects,16 or to answer fundamental questions about benefit–cost ratios for different projects undertaken in various laboratories.17

Assessment

As discussed in Chapter 2, the test of effectiveness focuses on the utility of the laboratory enterprise outputs and outcomes for the agency’s science consumers. The hallmarks are relevance, quality, cost effectiveness, and maximum usefulness in meeting the priorities and anticipated needs of the program offices and regional offices. Communication throughout the agency, as discussed below, provides the foundation for the planning and implementation phases of the work of the laboratory enterprise. The assessment phase provides verification of the process and informs planning and budgeting for laboratory activities.

Most successful organizations use both internal and external mechanisms for assessment. (Principle 4-4) The ORD planning process described in Chapter 2 provides the internal feedback for the relevance and utility of the outputs of the ORD laboratories. Also the proximity (in both location and relationships) that the program office and regional office laboratories enjoy with their offices should generally ensure that their outputs are relevant and useful for the decision-making undertaken by their offices, and these laboratories do undertake some systematic internal assessment. Expansion of the planning and implementation processes recommended above would probably provide a step in the right direction toward such an internal assessment process. In addition, it is important for managers to focus specifically on such questions as the following:

- Are the results of sufficient quality to be useful?

- Does the research address the problem, and is it ready for implementation?

- Does the work continue to reflect current program or compliance priorities?

EPA’s program office laboratories and regional office laboratories should undergo regular internal reviews of their efficiency and effectiveness. (Recommendation 4-7)

ORD not only has an internal assessment process but uses external review for assessment. In particular, the Board of Scientific Counselors (BOSC), a committee convened under the Federal Advisory Committee Act (FACA), is charged with providing technical and management advice regarding ORD’s research program and program plan development.18 The BOSC executive board meets three times a year with ORD and conducts a continuous peer review of ORD’s centers, laboratories, and research programs aligned with ORD’s 5-year strategic plan. The review includes midcycle program progress assessments. The BOSC focus is to ascertain that the right science is being done and that it is being done well in sup-

_________________________

14Although this may seem a daunting task, it is akin to the information that proposers routinely submit as part of the grant-submission process and then at the conclusion of the work done under the grant. In the era of big data, this information is “knowable”. For instance, the statistical agencies have long been able to calculate the cost per case for each survey respondent.

15Surely, several regional office laboratories undertake substantially similar measurement or testing projects for their regional offices; although the work may be the same, the costs may not be (for a variety of reasons).

16EPA reports on the success of the Ann Arbor vehicle-testing laboratory, but the committee is not aware of any data on the budget of the laboratory, how much a specific testing project costs, or how the cost compare with those of external laboratories.

17For instance, in retrospect the actual costs of the very successful polychlorinated biphenyls project in Region 1 might be trivial compared with the benefits of the project.

18BOSC communicates to the EPA administrator through the assistant administrator for ORD. When a federal agency establishes an advisory group, the agency may be required to comply with FACA if the group has one or more members who are not federal government employees. See EPA 2010.

port of the strategic plan and EPA’s mission. BOSC has reciprocal liaison with EPA’s Science Advisory Board (SAB), another FACA committee, which has a broader technical mandate to advise the agency on program development, research planning, and research-program balance, including implementation of the Strategic Research Action Plan. The SAB also reviews specific guidance, white papers, and reports that result from ORD and program office activities. However, such requests are ad hoc, and there is no similar process for external review of the outputs of the program office and regional office laboratories. Given the benefits of the external reviews, but recognizing that they are not cost-free, either in money or in person-hours of relevant EPA staff, the committee recommends that EPA expand the use of external reviews to cover all components of its laboratory enterprise. (Recommendation 4-8)

Communication

This chapter has included a number of recommendations for improving the management processes in the laboratory enterprise. Our objective is to help EPA to think about the enterprise not so much as a group of individual components but as a system of various scientific and technical efforts within EPA all of whose various laboratories support and advance the agency’s mission. To that end, the most important process —and the glue that will hold the enterprise together—is communication.

As emphasized in summary principle 7, communication in an organization goes to the heart of what the organization is about. Effective communication helps to keep employees working well together and reinforces the best tendencies of an organization. Tight-knit organizations thrive on and depend on close communication. It is even more important in a diversified and distributed enterprise to share information about priorities, practices, and problems. Without adequate communication, misunderstandings can develop, employees can begin to work at cross-purposes, and unnecessary rivalries can develop.

In EPA, with its strong science perspective and multifaceted laboratory enterprise, effective communication is central. It is especially true because EPA maintains a small but diverse laboratory enterprise with a small fraction of the funding available to the larger federal science agencies. It is especially important if EPA is to navigate the process of looking 10 years out in its research agenda.

Like all federal agencies, EPA maintains a matrix management system in which most employees have more than one supervisor or boss. Typically, science employees may have an EPA headquarters boss, a programmatic or regional boss, and bosses who represent particular science disciplines. There is nothing wrong with that situation, and it is unavoidable in a complex, technical federal organization like EPA. But effective communication within and between units is essential to making it work. That means that the program offices and their laboratories need to have close communication with all elements of the laboratory enterprise so that each of the various EPA laboratories understands intimately the needs of the program offices. The program office laboratories are not designed or staffed to solve all the problems that their programs or regions present. The programs therefore reach out to the rest of the EPA laboratory enterprise. It is important for the communication to be two-way so that program offices can stay up to date on what the various laboratories are doing and its relevance to program needs and similarly for the regional offices and their laboratories.

All that requires not only frequent communication but the maintenance of a variety of lines of communication, some of which exist in and some of which will be new to EPA. We recognize that there has been substantial progress in establishing and maintaining channels of communication throughout the agency and between ORD and the program offices and regional offices. For example, each regional office serves, on a rotating basis (see Table 4-1), as the lead regional office assigned with the responsibility for identifying and synthesizing the concerns of the 10 regions into an overall view to inform decision making in specific EPA offices outside of the regions. As another example, an ORD representative attends annual meetings of the regional laboratory directors. Also, the ORD laboratories maintain connections to the program offices through representatives assigned to those offices to ensure that the needs of the program offices are being met; this is a relatively new effort but will be useful for EPA.

TABLE 4-1 EPA Lead Region Assignmentsa

| Area of Responsibility | Lead Region FY 2013–2014 | Lead Region FY 2015–2016 |

| Office of the Administrator | 1 | 7 |

| Office of Environmental Information | 1 | 5 |

| Office of Administrator and Resources Management Office of the Chief Financial Officer | 2 | 9 |

| Office of Chemical Safety and Pollution Prevention | 3 | 1 |

| Office of Air and Radiation | 4 | 8 |

| Office of Homeland Security | 5 | b - |

| Office of International and Tribal Affairs | 6 | c - |

| Office of Solid Waste and Emergency | 6 | 2 |

| Office of Enforcement and Compliance Assurance Office of General Counsel | 7 | 6 |

| Office of Water | 8 | 4 |

| Office of Solid Waste and Emergency Response | 9 | 10 |

| Office of Research and Development & OA-Regional Science & Technology | 10 | 3 |

aA map of the EPA regions is shown in Figure 1-1 of Chapter 1.

bCombined with the Office of Solid Waste and Emergency Response

cCombined with the Office of the Administrator

Source: Adapted from EPA 2014k.

A question that EPA should consider is whether these efforts should be expanded and explicitly encompass the program office and regional office laboratories, which do not appear to be have established systematic lines of communication other than through their offices. We understand that the program office and regional office laboratories might participate in the weekly staff calls with the administrator’s office, (Szaro 2013) that the directors of the regional office laboratories meet with one another, and that there are often ad hoc conferences that include people from the program office and regional office laboratories.

EPA provided many examples of communication (indeed, collaboration) between program office and regional office laboratories and other centers of expertise, both in and outside EPA, and this suggests that such outreach is not unusual. To name a few, the National Enforcement Investigations Center has worked with ORD, program offices, and regional offices to develop techniques for its criminal investigations; the National Vehicle and Fuel Emissions Laboratory has coordinated with ORD on health-effects research with the Oak Ridge National Laboratory and Southwest Research Institute on truck and power-train test methods and with Argonne National Laboratory on vehicle test methods; and the Microbiology Laboratory, under the Office of Pesticide Programs, works regularly with the Food and Drug Administration, the Center for Disease Control and Prevention, the US Department of Agriculture, and state, local, and tribal governments.

Those and other examples are good and useful steps, but the connections are too important to be left to informal arrangements. Difficult issues can arise as the components of the laboratory enterprise seek to coordinate their work. For example, program and regional offices will need to balance the workloads and capabilities of their dedicated laboratories against the workloads and capabilities of the ORD laboratories; the decision-making process will entail having confidence that the laboratories not under their immediate control are aware of their needs and are bringing their best capabilities to bear. That will take close communication and may require new connections and linkages. It requires persistent management effort and attention; if management is not paying attention to sustaining these lines of communication, they will not achieve their objective. Employees know what is important to management and what is not and focus their efforts accordingly.

The challenge for EPA is to develop mechanisms that permit the effort required to sustain appropriate communication to be handled easily and efficiently, become second nature, and enhance the output and performance of all its laboratories. EPA should determine precisely what lines of communication are needed, which ones already exist, and which ones should be established. It should then clearly articulate the need for these avenues and the mechanisms by which they will be sustained. (Recommendation 4-9)

PULLING THE ENTERPRISE TOGETHER

The framework analyses provided in Chapter 2 provide criteria for evaluating the several components of EPA’s laboratory enterprise. The same criteria can be applied to the laboratory enterprise as a whole and help to guide future investments, planning, and implementing actions for it. We encourage EPA to develop and strengthen management processes using those criteria, which will enable the individual components to perform better and to be synchronized with each other. Our proposal is not to create an integrated entity but rather to enhance communication and coordination among the various components.

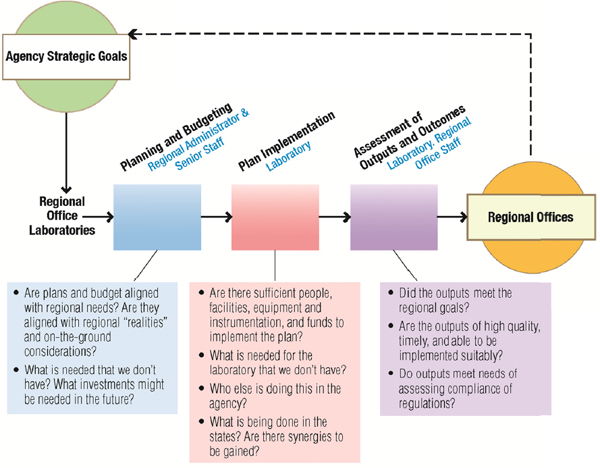

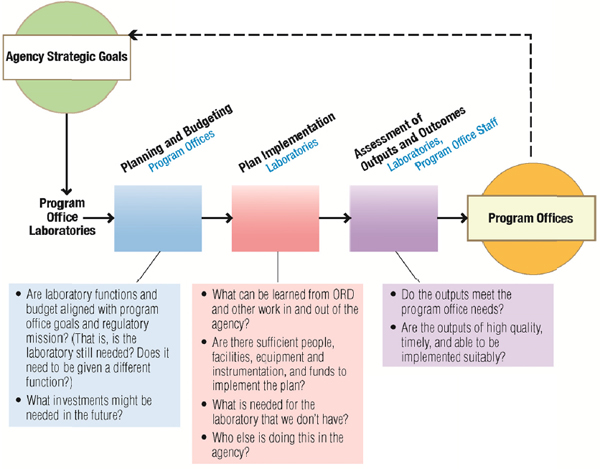

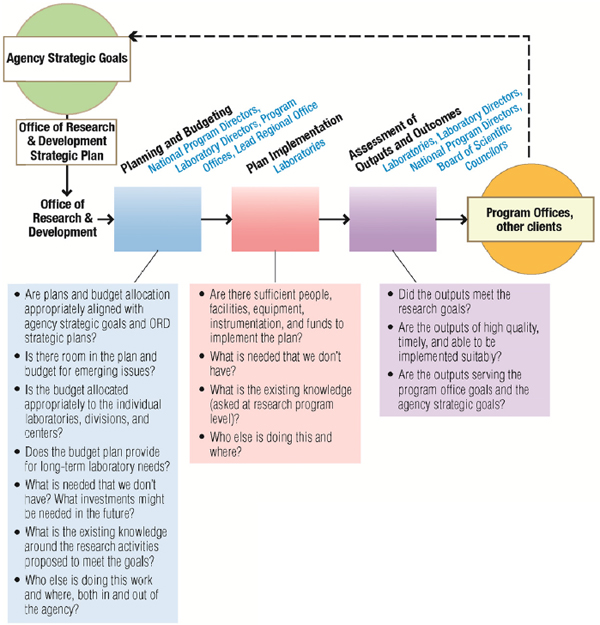

As discussed in Chapter 2, the general criteria of efficiency and effectiveness can be made specific in their application to the different components of the laboratory enterprise. Figures 4-1 through 4-3 include illustrative questions to be asked for each major component and for each phase in the planning–implementation–assessment cycle of each. Questions posed in these figures are aimed at helping EPA better align laboratory activities with the mission as called for in summary principle 2. Figure 4-1, for example, lists questions keyed to each phase of the cycle in ORD laboratories. Figures 4-2 and 4-3 offer comparable specifications for the regional office and program office laboratories, respectively.

FIGURE 4-1 Aligning agency strategic goals to the ORD portion of the laboratory enterprise.

Using the questions from Figures 4-1, 4-2, and 4-3, management can help to ensure the efficiency and effectiveness of each component of the laboratory enterprise but not necessarily of the enterprise as a whole. Although it is possible that the system functions optimally simply by having each component work well on its own, the agency has experienced substantial gains from greater coordination between ORD and the program offices and regional offices, and this suggests that additional benefits can be achieved by extending the coordination and communication throughout the agency. This experience includes ongoing technology transfers from ORD to the regional office laboratories (up to 20% of ORD’s work), the marshaling of agencywide resources to form the virtual ERLN, and the creation of laboratories with cross-EPA functions, such as the NCCT and the National Analytical Radiation Environmental Laboratory. It also includes single-event collaborations such as EPA’s response to the Deepwater Horizon oil spill in 2010. This experience is testimony not only to the fruitfulness of past coordination efforts but to the promise of measures to strengthen and systematize coordination in the future.

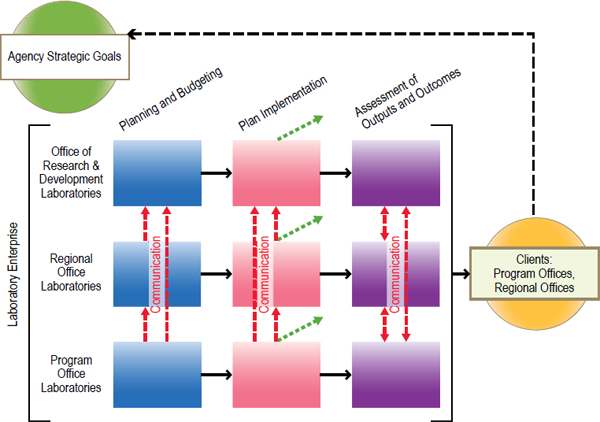

Figure 4-4 represents the laboratory enterprise as a composite of its three main components, which are represented separately above. The dotted lines connecting the components represent added efficiency and effectiveness to be gained through enhanced communication and coordination.

Cross-cutting questions analogous to those for the individual components can be framed for the laboratory enterprise as a whole. For example, at the level of planning and budgeting for the enterprise, it would be important to ask regularly

• Whether the agency’s laboratories have the right personnel, facilities, and equipment to perform their functions and whether those resources are allocated among functions in a way that maximizes the overall contribution to meeting the agency’s goals.

• Whether the right balance between meeting short-term needs and building long-term capacity is being maintained across the enterprise as a whole.

• Whether appropriate provision is being made for interdisciplinary or multimedia work that does not fit within the purview of an individual program office.

• Whether there are collaborations or other synergies that would enhance efficiency and effectiveness further. This last question would include potential collaboration not only among EPA laboratories but with other federal agencies, states and tribes, universities, and the private sector.

In implementation, questions that would benefit from an enterprisewide perspective include

• Whether there is sufficient capacity (workforce, facilities, and equipment) at the project or activity level.

• Whether additional needed capacity is available in the laboratory enterprise or from other federal agencies, states, universities, or the private sector.

• Whether redirection may be necessary in response to changed circumstances, including changes in immediate or long-term needs or priorities.

Finally, at the assessment stage, the agency could benefit from enterprisewide answers to such questions as

• Whether outcomes are meeting the needs of all affected program elements, when outcomes have multiple applications.

• Whether outcomes suggest the need for similar work elsewhere in the agency (for example, a regional office laboratory investigation to address a problem that may warrant attention in other regions or nationally).

• Whether systemic factors may be affecting performance throughout the laboratory enterprise.

• Whether practices that have improved the usefulness, timeliness, or cost effectiveness of the work of one component can be used to advantage elsewhere in the system.

FIGURE 4-4 The overall laboratory enterprise with emphasis on lines and directions of communication that should be institutionalized. In addition to communication, the dashed red lines represent coordination within the enterprise; the dotted green lines under “Implementation” indicate where EPA must reach out to other agencies, academe, and other research organizations to inquire about what is going on concurrently in relation to a given science need.

The Agency is already asking some of those questions and acting on answers to them through processes specific to each component of the laboratory enterprise and informal networks that operate among them, as described earlier in this chapter. The gains from informal collaboration persuade us, however, that the laboratory enterprise would realize even greater benefits from more formal and systematic arrangements for communication and coordination. For that reason, we strongly urge EPA to use the frameworks presented in Figures 4-1 through 4-4 for the individual components of the laboratory enterprise and for the laboratory enterprise as a whole. (Recommendation 4-10)

We are not recommending that the entire enterprise be directed or managed by a single person, nor are we recommending that it be operated as a single entity. On further examination, we believe that the Government Accountability Office (GAO) understanding of the diverse components of the laboratory enterprise and their ability to contribute to the mission of the agency in different ways may have been incomplete and may have led GAO to oversimplify its recommendation. Rather, we envision that the enterprise would seek to preserve the strengths of the individual components but provide for more systematic communication and coordination among them. We discussed enhanced communication above and recommended that it build on the lines of communication that already exist. Similarly, enhanced coordination can be built on existing networks and processes.

There are several possibilities for structuring the coordinating entity. One option would be to use the existing Science and Technology Policy Council (STPC), an agencywide committee that is chaired by the science advisor, who reports to the administrator and deputy administrator. The objective is to have participants with diverse backgrounds and experience provide familiarity and authority with the operations of the various components of the enterprise. An alternative option would be to task the EPA deputy administrator, the science advisor, or the ORD assistant administrator with responsibility for overseeing an assemblage of relevant people from the various components of the laboratory enterprise and to give the pro-

gram office and regional office laboratory managers dotted-line (secondary or indirect) responsibilities to that person. We have identified several available options, the committee recommends that the means of implementing the vision for the laboratory enterprise be determined by the EPA administrator with a view to meeting the functional criteria set forth in this report for enhancing the efficiency and effectiveness of the enterprise. (Recommendation 4-11)

We recognize that the STPC has already been assigned some functions and that it has several subgroups, one of which is designated as a working group for the EPA laboratory enterprise.19 But, as discussed above, EPA has not thought of its various laboratories as an organized composition of diverse components, and most of the efforts of the working group have been related to one or more of the components. With the reorientation suggested above and given the importance of enhanced communication and coordination, the tasks of the managing entity for the enterprise could well include a needs assessment, an inventory of equipment and facilities, an inventory of skills, and development of training programs. Here, as above, although we have identified some tasks for the managing entity, the committee believes that the design of a suitable communication and coordination function is for the administrator and the administrator’s senior team.

We are sensitive to the concern that communication and coordination themselves are not costless and that efforts to overspecify dispersed systems, such as EPA’s laboratory enterprise, may impose more burdens than benefits. The test of any move toward greater coordination is whether it improves the efficiency and effectiveness of the whole enterprise when costs of coordination are taken into account. We are persuaded, however, that a properly reoriented EPA laboratory enterprise could be more efficient, make greater contributions to achieving the agency’s goals, and have more effective interactions with other agencies and with the larger scientific community, both nationally and internationally.

COLLABORATION WITH ENTITIES BEYOND EPA

The committee’s charge states that the committee “will develop principles for the efficient and effective management of EPA’s Laboratory Enterprise to meet the agency’s mission needs and strategic goals” while “recognizing the potential contributions of external sources of scientific information from other government agencies, industry, and academia in the U.S. and other nations [emphasis added].” Summary principle 9 emphasizes this need for linkages to universities, industry, and other government partners. A closely related consideration is the need to avoid duplication of capabilities readily available outside EPA, as called for in summary principle 3. EPA has a broad array of responsibilities and mandates, and its mission requires a wide variety of scientific knowledge, much of which needs to be based on data produced by scientific laboratories through experimentation and analysis of environmental samples. The US national research program related to environmental science is extensive and extends well outside the boundaries of EPA. The federal government supports research in environmental science that is useful for EPA’s mission through many programs and agencies, including the National Science Foundation, the Department of the Interior, the Department of Energy, the National Institutes of Health, the Department of Defense, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, and the National Aeronautics and Space Administration. Research is also conducted in universities, in national laboratories, and by various other contractors. And research and collection of environmental data are undertaken by state agencies, private industry, nongovernmental organizations, and consulting firms. Furthermore, as noted in

_________________________

19According to EPA’s Web site, “The Science and Technology Policy Council (STPC) serves as a mechanism for addressing EPA’s many significant science policy issues that go beyond regional and program boundaries. With a goal of integrating policies that guide Agency decision-makers in their use of scientific and technical information, the STPC works to implement and ensure the success of selected initiatives recommended by external advisory bodies such as the National Research Council and the Science Advisory Board, as well as others such as the Congress, industry and environmental groups, and Agency staff. In this way, the STPC contributes guidance for selected EPA regulatory and enforcement policies and decisions.” (EPA 2013b)

the charge to the committee, the United States does not have an exclusive claim to research in environmental science: relevant research is also conducted in other countries.

An effective EPA laboratory enterprise should be fully cognizant of the array of research conducted outside EPA laboratories, should have mechanisms and programs to capitalize on that scientific work, and should have plans and staffs in its own laboratories not only to accomplish work necessary for its mission but to complement efforts of other agencies and to provide a means of collecting, sorting, and analyzing the results of those efforts to serve EPA’s mission. (Principle 4-5) There is evidence that EPA does this and that it recognizes the need to incorporate relevant non-EPA research. Several specific examples of collaboration with other agencies and universities were provided to the committee (such as collaborations between EPA laboratories and the California Air Resources Board to develop approaches for improving air quality). However, the preponderance of information and the overall tenor of our discussions with EPA managers suggested that EPA is focused mostly on internal organization and on the procedures for distributing needed work among the EPA laboratories.

The primary mechanism that we are aware of for engaging universities in work related to EPA’s mission is the Science to Achieve Results (STAR) program, which we believe is a valuable and effective means of meeting some part of the need to use outside expertise. The STAR program, however, is small relative to the overall US and international effort in environmental science. It is also small relative to the ORD budget. As discussed in Chapter 3, training grants constitute a mechanism for building bridges to the university research community, as does the reinstitution of the postdoctoral program. Both programs can provide the types of expertise needed to conduct research either within the agency laboratory system or in a university laboratory. The committee endorses both programs because they can enhance the awareness of mission-relevant research performed outside EPA. In addition, EPA should reconsider the undergraduate and STAR graduate fellowships in environment-related fields that are no longer offered in 2014). Such programs seem to be important if EPA is to provide a foundation in environmental science and engineering that would allow flexibility for it either to have relevant research performed outside EPA or to acquire staff for its inhouse expertise.

In addition to reaching out to universities, EPA has established a diverse set of industry partnerships.20 For example, the Automobile Industry/Government Emissions Research (AIGER) Cooperative Research and Development Agreement (CRADA)21 was set up to identify, encourage, evaluate, and develop instrumentation and techniques for measuring emissions from motor vehicles accurately and efficiently. The technologies developed under that CRADA are intended to be commercialized and be made readily available for emission-testing activities. It is important for EPA to communicate internally throughout the organization about such private-sector interactions and their potential benefits, such as benchmarking EPA laboratories against laboratories doing similar work in the private sector.

EPA clearly needs to have a substantial amount of high-quality inhouse scientific expertise and laboratory capabilities because it typically needs to answer specific questions related to regulation and enforcement and questions related to environmental effects of specific chemicals, activities, and processes. Other entities may produce relevant information in many circumstances, but it is EPA that must have the expertise to recognize the relevance of information, evaluate its quality, and synthesize it for specific purposes. EPA is also faced with situations in which research or analytic work is urgent, so it is imperative that it have access to dedicated staff and facilities that can respond quickly to such needs. Although we can surmise and in some cases identify which of EPA’s laboratory facilities and associated scientists are required for the agency’s mission, it would behoove the agency to develop criteria for determining which capabilities need to be maintained inhouse and which potential new capabilities that might be required in the future should be developed inhouse as opposed to being acquired through partnerships. Such an ap-

_________________________

20EPA’s Office of Acquisition Management provides information on current procurement opportunities (EPA 2014l).

21Members of the AIGER CRADA are EPA, the California Air Resources Board, and the US Council for Automotive Research, which includes Chrysler LLC, Ford Motor Company, and General Motors Corporation (EPA 2013c).

proach would be consistent with summary principle 3, which is concerned about avoiding duplication of capabilities that are readily available externally.

Many problems require specific data to be generated to address environmental issues, but data are being generated globally at an enormous rate, and this has created the challenge of maintaining the capability to take advantage of the rapidly expanding knowledge base. It is critical for EPA to have a strong capability for accumulating, managing, and mining extremely large datasets from diverse sources related to its mission. Such a capability is a critical component of efficient use of its laboratory facilities and scientific staff.

Assuming that effective use of the agency’s scientific and technical capabilities requires optimal use of non-EPA scientific resources, there should be a process by which identified research priorities are accompanied by assessment of whether further research is needed and then assessment of the best way to obtain that research. Presumably, it might be preferable in many cases to partner or contract with other agencies to obtain the needed research, and it might be best in an equal number of cases to have the research done by EPA scientists in EPA laboratories. Although we have been given evidence that much of that process is used, we did not see an explanation of how it is determined whether and which outside sources of information should be used. EPA should develop more explicit plans for partnering with other agencies (federal and state), academia, industry, and other organizations to clarify how it uses other federal and nonfederal knowledge resources, how it maintains scientific capabilities that are uniquely and critically needed in the agency, and how it avoids unnecessary duplication of the efforts or capabilities of the other agencies. (Recommendation 4-12)

![]()

As discussed above, the committee was not tasked with reorganizing or redesigning the EPA laboratory enterprise. However, in suggesting the principles and recommendations that we have developed, we believe that EPA now has the tools needed to design and implement a plan for enhancing the efficiency and effectiveness of its network of laboratories.