The primary goal of Army Research Laboratory (ARL) programs that fund and support research is to improve the combat readiness, efficiency, and survivability of U.S. warfighters – by developing and deploying technologies that will serve that basic imperative. How do ARL programs that support investigators and programs at historically black colleges and universities and minority institutions (HBCUs/MIs) further the fundamental goals of improving America’s warfighting capabilities? In the current technologically innovative era, the answer is straightforward: The United States must have a strong and expanding intellectually talented and practically trained workforce in STEM disciplines. Underrepresented minorities (URMs) make up growing parts of the overall U.S. population, and even though historically black and other minority-serving colleges and universities are relatively few in number in the overall universe of U.S. colleges and universities, they continue to enroll a disproportionate share of minority students.1, 2 These institutions are critical to the education and scientific and technical training of the minority component of the diverse cadre of engineers, mathematicians, and scientists on which the military depends for effective warfighting technologies. HBCU/MI universities are one of the ways the United States, including the U.S. Army and other military departments, can ensure a fully mobilized, diverse workforce.

The recruitment and effective education of intellectually talented students requires strong, dynamic academic institutions. The capabilities of colleges and universities matter as much as the credentials of the students they enroll. Effective science and technology education at HCBU/MIs depends upon these institutions’ capacity to attract and retain capable faculty, gifted students, and postdoctoral researchers, providing them with appropriate facilities and infrastructure to support their scientific activities. ARL has contributed to building up the human and infrastructural capacities of HBCUs/MIs in the past, and the committee has looked for ways to enhance the impact of the ARL program on institution-building in the future, confident that more capable black and minority-serving institutions will, in turn, help the United States develop a more diverse and intellectually capable STEM workforce.

An active HBCU/MI program is under way at ARL. ARL identified for the committee five objectives for its programs supporting HBCUs/MIs:

1. Foster support for meritorious research proposals originating at HBCUs/MIs;

2. Assist HBCUs/MIs in strengthening their capability to conduct quality research of interest to the Army;

3. Assist in the development of or enhancement of science and engineering education programs at HBCUs/MIs;

_________________

1Dexter Mullins, “Historically black colleges in financial fight for their future,” Al Jazeera America, October 22, 2013, http://america.aljazeera.com/articles/2013/10/22/historically-blackcollegesfightfortheirfuture.html.

2Education Encyclopedia, “Hispanic-Serving Colleges and Universities—The History of HSIs, HSIs and Latino Educational Attainment, Conclusion,” http://education.stateuniversity.com/pages/2045/Hispanic-ServingColleges-Universities.html, accessed May 25, 2014.

4. Increase the participation of URMs in research and development; and

5. Coordinate ARL’s HBCU/MI programs with similar programs in other federal agencies.

ARL has also noted as follows on its website:3

The objective of the U.S. Army Research Laboratory’s (ARL’s) Historically Black Colleges and Universities/Minority Institutions (HBCU/MI) program is to address the projected shortfall of scientists and engineers among the diverse populations of the 21st century, leverage HBCU/MI technical capabilities to fulfill ARL requirements, and expand the involvement of HBCU/MIs in ongoing research at ARL. ARL presently has Education Partnerships with six HBCUs/MIs.

However, ARL reported that there is no formal policy directive at the ARL or the Army that describes a vision or strategy for the enhancement of STEM capability or other goals at HBCUs/MIs, and no metrics for assessing the success of ARL’s programs that support these institutions.

ARL is charged with conducting research and development to support the technological needs of the Army and of others that support it with reimbursable funding. This charge is consonant with the objective of assisting HBCUs/MIs in strengthening their ability to conduct quality research of interest to the ARL’s mission and is focused on technology results. ARL provides on its Internet website4 the following description of the mission for its Army Research Office:

The U.S. Army Research Laboratory’s Army Research Office (ARO) mission is to serve as the Army’s premier extramural basic research agency in the engineering, physical, information and life sciences; developing and exploiting innovative advances to insure the Nation’s technological superiority.

To fulfill its charge to support the technology needs of the Army, ARL needs to consider its own workforce development and that of others who participate in advancement of Army technological capabilities. In that regard, fostering workforce diversity is an obvious goal; however, workforce diversity was not identified by ARL as one of the objectives listed above. Like most other organizations in the Department of Defense (DoD), ARL pursues admirable DoD-wide and national societal goals as recognized by the objectives of increasing the participation of underrepresented minorities in research and development, fostering support of meritorious research proposals originating at HBCUs/MIs, and helping HBCUs/MIs to develop and enhance STEM education programs.

ARL’s stated objectives for its programs supporting HBCUs/MIs are not internally consistent and do not benefit from a top-level Army or ARL policy directive. ARL could establish a vision, strategy, and set of metrics to assess success in areas related to HBCUs/MIs: institutional STEM capability, contribution to Army STEM workforce diversity, contribution to Army technology advancement, and/or other DoD or national goals.

ARL has as one of its goals in funding HBCU/MI programs, enhancing the institutional development at the recipient institution. The highly respected array of research universities in the United States is a model that is now replicated in most developed and developing countries. The development of this educational system began soon after the Second World War, when few government science and technology (S&T) programs existed and few of them were carried out at universities. The few universities

_____________________

3U.S. Army Research Laboratory, “HBCU/MI,” last update/reviewed November 3, 2010, http://www.arl.army.mil/www/default.cfm?page=39.

4Ibid.

that offered advanced degrees in the sciences and engineering undertook modest amounts of research, often funded by local industry. Several schools had already begun to develop strong departments, based on the European models, and in many cases peopled by émigrés from the stressed European systems.

The success of government-funded research in the prosecution of that war (e.g., the atomic bomb, radar, and jet propulsion), highlighted in Vannevar Bush’s report Science, The Endless Frontier,5 led to the subsequent establishment of DoD agencies in the Air Force (AFOSR) and Army (ARO), mimicking the already existing Office of Naval Research (ONR), as well as organizations such as the Atomic Energy Commission, the National Science Foundation (NSF), the National Institutes of Health, and the National Aeronautics and Space Administration, each committed to funding research at universities. The university community responded; those universities that already had strong departments were in the vanguard, but there was funding and strong incentive for other universities to perform S&T research.

The typical university at the time was primarily a teaching institution, targeted at producing enough teachers, mining and petroleum engineers, and agriculture-related professionals to satisfy the local economy. The path to research was clear, however: identify an area of a discipline to pursue, hire appropriate faculty (especially proven senior researchers) to establish the base, obtain federal funding for the targeted area, recruit graduate students, acquire facilities, establish STEM curricula, and add additional faculty over time.

Federal research programs drove the selection of target areas for development and supplied the critical resources required to hire faculty, capitalize research facilities and equipment, and fund the graduate students and research projects. In this environment, through the 1980s, several of the small teaching colleges transformed into large research universities. Then the federal funding leveled off (in real terms) just as the U.S. population grew from approximately 238 million in 1985 to 317 million in 2014, with African Americans, Latinos, Native Hawaiian and other Pacific Islanders, and American Indian or Native Alaskans comprising at least 36.5 percent of the U.S. population by 2012.6 Universities that achieved research success during the years of budget growth were no longer so readily or easily emulated. Areas for potential federal funding were focused on already targeted areas at research universities. It was in this new reality that HBCUs/MIs were making their way from primarily four-year teaching colleges to research institutions. Universities realized that true institutional development requires funding targeted areas of disciplines for many years as faculty and facilities are added and developed. The infrastructure requires continual funding to maintain and enhance program capability. When successful, HBCUs and similar latecomers to the university research scene pulled all of these elements together from disparate sources—for example, state money, local donors, foundations, research funding from various federal agencies, and industry partnerships—to form a STEM institutional capability.

Many HBCU/MI institutions receive grants for small, single principal investigator (PI) programs; some have been centers of excellence, others have participated in multiyear, multiperformer projects, and some have received funds for all three of these broad categories. It is the last two categories through which sizable and competitive STEM capabilities have been established. All ARL HBCU/MI programs contribute to STEM programs, but those ARL programs that are multiyear and/or that collaborate with other research universities or with ARL researchers have achieved the most recognizable enhancement of institutional STEM capability. Individual grants provide flexibility and (if so targeted) excellent start-up resources, but they are not very effective in developing significant local strength. Cooperative grants and contracts do offer such possibilities, but they too must be managed in a manner intended to accomplish a well-defined institution-building goal that yields mutual long-term value for the Army and the university.

______________

5NSF Office of Scientific Research and Development, 1945, Science, The Endless Frontier—A Report to the President, United States Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C.

6U.S. Census Bureau, “State and County Quickfacts,” http://quickfacts.census.gov/qfd/states/00000.html, accessed May 25, 2014.

Starting in 1987 funding in support of HBCUs/MIs was governed by statute 10 USC 2323, wherein a goal was established that 5 percent of DoD contracts should go to small, disadvantaged businesses and HBCUs/MIs. In 2010, that statute was replaced by 10 USC 2362, which eliminated goals and “set asides” for small, disadvantaged businesses and HBCUs/MIs. Today, ARL, like other DoD organizations, continues to support HBCU/MI programs, but absent statutorily set goals.

OVERVIEW OF ARL FUNDING PATHS FOR HBCUs/MIs

ARL is the Army’s corporate research laboratory, providing the underpinning science, technology, and analysis that enable full-spectrum operations. It has a substantial multidisciplinary in-house capability within seven divisions (six laboratory directorates and the ARO). It also issues contracts, grants, and cooperative agreements for work by extramural research performers (e.g., industry, other federal laboratories, and universities, including HBCUs/MIs).

The ARO invests Army basic research funding with extramural performers, principally universities. The ARO manages a core HBCU/MI program for ARL and the Army. The ARO also serves as the executive agent for the OSD’s HBCU/MI funding (this funding is not considered in this report). Program managers in the other six divisions of ARL can and do include HBCUs/MIs in their programs. ARL’s Outreach Program office monitors and encourages interaction with HBCUs/MIs.

ARL (including its ARO) selects HBCU/MI performers based on the quality of responses to Broad Agency Announcements (BAAs) or requests for proposals (RFPs). Grants or cooperative agreements to conduct research on particular technical matters are concluded between ARL and those HBCUs/MIs that are selected after reviewing the responses to BAAs. Grants are typically, but not exclusively, between ARL and a single PI and include some funding for his/her graduate or undergraduate research student(s). Cooperative agreements take several forms, but typically an HBCU/MI will be a partner with ARL, with another or other universities, or with industry. Contracts are concluded between ARL and a selected HBCU/MI performer when the applied research involves a deliverable product.

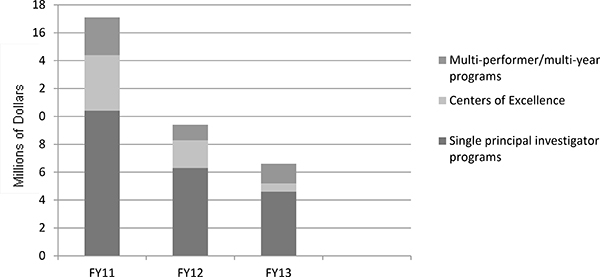

ARL has many options to deploy funding to HBCUs/MIs. The most common have been grants to single PIs, centers of excellence (which are being phased out), and multiyear, multiperformer cooperative agreements; Figure 2.1 depicts recent funding, and Chapter 5 and the appendixes describe the various programs in more detail.

While HBCU/MI programs are important to ARL for technical mission achievement, workforce enrichment, and DoD (or other national) societal priorities, the ARL investment in HBCUs/MIs is not large in relative terms and has even been declining in recent years. The ARL annual budget from Army sources and from work it does for others is approximately $1.3 billion, of which approximately $700 million is for Army research and development funding; the rest may be generally characterized as reimbursable work for other agencies. The average annual ARL support for all HBCU/MI programs has been approximately $11 million annually over fiscal years FY2011, FY2012, and FY2013. Figure 2.1 shows a top-level summary of the funding amounts and percentages of the total investment for the various ARL programs for HBCUs/MIs for 3 recent fiscal years. Multiyear, multiperformer programs in Figure 2.1 include Partnership in Research Transition (PIRT) programs, Cooperative Technology Alliances (CTAs), and Cooperative Research Alliances (CRAs).

FIGURE 2.1 ARL investments in grants and programs to HBCUs/MIs, fiscal years FY2011-2013. Multiyear/multiperformer programs include the Partnership in Research Transition (PIRT) program, Cooperative Technology Alliances (CTAs), and Cooperative Research Alliances (CRAs). Single principal investigator programs include HBCU/MI ARO core grants in the following amounts: FY2011 ($3.6 million), FY2012 ($3.3 million), and FY2013 ($2.5 million).

ARL has supported a wide variety of HBCU/MI projects, with the stipulation that projects support ARL mission research, which covers such disciplines as computational science, materials science, ballistics, sensors, electron devices, survivability, vehicle structure and mobility, and human sciences. While ARL HBCU/MI programs do contribute to STEM programs at HBCUs/MIs, they are not substantial enough to significantly enhance the institutional STEM capabilities. Moreover, they are relatively small when compared with ARL’s total annual funding, and they are declining, especially for the HBCU/MI programs that have the most impact: those that involve multiperformer agreements and/or multiyear funding.

HBCU/MI PROGRAMS AT OTHER MILITARY DEPARTMENTS

The committee was tasked to identify ARL practices with regard to HBCUs/MIs that may be useful to other military departments. The committee was briefed by the U.S. Air Force and the U.S. Navy on their respective HBCU/MI programs. The briefings and associated discussions described core HBCU/MI support in those military departments for single PIs and creative programs that focused on strategic HBCU/MI priorities, such as workforce development. The discussions showed that the Army, Air Force, and Department of the Navy are intimately familiar with each other’s arrays of HBCU/MI programs. Each military department has unique HBCU/MI programs tailored to its needs and culture. The various ARL multiyear, cooperative agreement programs are unique among the military departments, and they are well known by one another; considering their level of funding, discussions with selected HBCUs/MIs suggest that these programs successfully support institutional STEM improvement.

SUPPORT FOR UNDERREPRESENTED MINORITY FACULTY AND STUDENTS

The majority of PIs supported by ARL HBCU/MI programs have not been African American, Hispanic, or Native American. Over the past 10 years, the numbers and percentages of the 220 principal investigators funded by ARL have been 102 (46 percent) Caucasians, 14 (6 percent) African Americans, 11 (5 percent) Hispanics, 47 (21 percent) Middle Eastern and South Asians, 46 (21 percent) East Asians, and 0 Native Americans.

These findings are disconcerting but understandable. A primary requirement for participation in ARL programs supporting HBCUs/MIs is that the supported STEM research contribute to developing and transitioning technologies that enhance the safety and effectiveness of Army warfighters. There is a dearth of African American, Hispanic, and Native American researchers at HBCUs/MIs in STEM fields relevant to ARL activities. Over the past 20 years, many minority faculty have left HBCUs/MIs and joined nonminority institutions, drawn by factors that include higher salaries and opportunities to work with more advanced equipment than that typically available at HBCUs/MIs. There is a tendency for recent URM graduates with Ph.D.’s in STEM fields to join the faculty at nonminority institutions, for similar reasons. Native American colleges and universities have particularly low levels of ARL-relevant researchers and supporting equipment.

Given the constraints on available URM faculty at HBCUs/MIs, ARL’s funding of non-URM researchers at these institutions has helped to build institutional STEM capabilities at the institutions. The funded researchers establish and maintain STEM research programs, instruct undergraduate and graduate students, work collaboratively with postdoctoral researchers, and secure funding and equipment to support the students and postdoctoral researchers.

To achieve the goal of increasing the number of URM researchers working in STEM areas at HBCUs/MIs, it is first necessary to make every effort to reach out to HBCUs/MIs to make sure that ARL opportunities are widely known. Sponsoring broadly announced, periodic information dissemination symposia at which opportunities and program processes are elucidated would be helpful, especially if followed by proactive and regular mentoring of HBCU/MI candidates for funding on the BAA selection and program execution processes and on identification of other funding and collaboration opportunities within the Army.

It will also be necessary to support the students and postdoctoral researchers who will grow the ranks of future URM faculty and to help the institutions attract and retain the URM faculty. ARL could consider ways to expand the support at HBCUs/MIs of students serving as research assistants on ARL-sponsored projects. Multiyear (e.g., a 5-year norm) grants for single principal investigators and collaborative/cooperative agreements would support graduate students through completion of their theses and dissertations. This approach could be beneficially augmented by increasing the sponsorship of internships at ARL and by virtual internships with ARL laboratories and other laboratories. Other agencies (e.g., NIH and NSF) offer models for consideration that support minority undergraduate and graduate research students, summer interns, postdoctoral fellows, and faculty researchers.

To help attract and retain URM researchers at HBCUs/MIs, ARL could seek ways to provide public recognition and visibility for the sponsored research. Mentoring HBCU/MI faculty in the processes for applying for sponsored research and helping to alleviate administrative burdens associated with such research would contribute to overcoming current administrative challenges that could otherwise be one factor motivating researchers to move from HBCUs/MIs to larger institutions with more administrative support. Increasing HBCU/MI involvement in collaborative funded programs could be associated with opportunities for HBCU/MI investigators to share equipment with collaborators, and such collaboration also yields rewards with respect to research opportunities, recognition, and visibility in the S&T community.

Many research students at HBCUs/MIs are not from underrepresented minority (URM) groups, and some (especially graduate students) are not U.S. citizens.

The HBCU student body is still overwhelmingly black,7 while Hispanic-serving institutions (HSIs) are increasingly highly heterogeneous.8 Because of the relative homogeneity of the HBCU student population, the likelihood that URMs have access to cutting-edge research activities is higher at HBCUs than at HSIs.

There are 105 HBCUs in 20 states, the District of Columbia, and the U.S. Virgin Islands; though they represent less than 3 percent of all colleges and universities, they are responsible for awarding 18 percent of all degrees earned by black undergraduates. Although their enrollments are becoming more diverse, the vast majority of HBCUs continue to be predominantly black institutions: Black students make up more than 90 percent of the enrollments at 47 HBCUs and more than 75 percent of the enrollments at 80 HBCUs; moreover, black students are in the minority at only 7 HBCUs.

Most HSIs were not originally established to serve a particular student population. HSIs are generally characterized by their enrollment ratios rather than by their institutional mission, though there are several exceptions. HSIs represented 6 percent of all institutions of higher education in 2003, enrolling about half of all Latino undergraduates.9 The number of HSIs has grown dramatically, but there are only unofficial lists like the Department of Education’s list of High Hispanic Enrollment Institutions10 or information contained in Title V Developing Hispanic-Serving Institutions Program (Historical List of all Grantees).11 The Excelencia in Education group reported that the nation had 370 HSIs in 2013, an increase of roughly 60 percent from the 242 colleges that met the definition in 2003.12

Despite the fact that many ARL-supported faculty and research students at HBCUs/MIs have not been from URM groups, ARL HBCU/MI funding has generally enhanced STEM capability at the funded institutions and therefore has the potential to benefit URMs in STEM learning and research.

For at least its collaborative and multiyear HBCU/MI programs, ARL encourages summer internship programs, at ARL or similar Army facilities, for research students supported by ARL HBCU/MI funds. Such arrangements can be useful to the student and the funded research by, for example, exposing the student to leading-edge research efforts and researchers collaborating on ARL projects, providing access to sophisticated equipment at ARL, and providing familiarity with ARL staff, equipment, and facilities that may encourage subsequent applications for positions at ARL or later work with ARL in other contexts. However, such internships can conflict with progress-toward-degree plans or can be geographically inconvenient.

____________

7M. Christopher Brown II and Ronyelle Bertrand Ricard, The honorable past and uncertain future of the nation’s HBCUs, National Education Association Higher Education Journal, Fall 2007, pp. 117-130, http://www.nea.org/assets/img/PubThoughtAndAction/TAA_07_12.pdf.

8Lindsey E. Malcom-Piqueux and John Michael Lee, Jr., “Hispanic-Serving Institutions: Contributions and Challenges,” College Board Advocacy and Policy Center Policy Brief, October 2011, http://advocacy.collegeboard.org/sites/default/files/11b_4853_HSBC_PolicyBrief_WEB_120110.pdf.

9Education Encyclopedia, “Hispanic-Serving Colleges and Universities—The History of HSIs, HSIs and Latino Educational Attainment, Conclusion,” http://education.stateuniversity.com/pages/2045/Hispanic-ServingColleges-Universities.html, accessed May 25, 2014.

10U.S. Department of Education, “Accredited Postsecondary Minority Institutions,” http://www2.ed.gov/about/offices/list/ocr/edlite-minorityinst-list-hisp-tab.html, accessed May 25, 2014.

11U.S. Department of Education, “Title V Developing Hispanic-Serving Institutions Program Historical List of All Grantees,” http://www2.ed.gov/programs/idueshsi/hsi-allgrantees.pdf, accessed May 25, 2014.

12C. Dervarics, Hispanic-serving institutions continue growth with more poised to join ranks, Diverse: Issues In Higher Education, February 25, 2014, http://diverseeducation.com/article/60920/.