In its description on the Internet of its partnership programs, the Army Research Laboratory (ARL) notes as follows:

With the current pace of technology advancement, insular research and development (R&D) organizations will rapidly lose relevance and value. ARL has adopted business practices that have created a collaborative research environment between it and the private sector in select technology areas. ARL has also provided the Army access to private sector sources of research with the requisite diversity and quality. Currently, ARL outsources 80 percent of its research program to academia with over 250 academic partners in all 50 states and to industry through a mix of grants, cooperative agreements, other transactions authority, or contracts.1

In addition, ARL has continued to support single principal investigator (PI) projects, a tested model for the identification of leading researchers with entrepreneurial talents and skills.

ARL SINGLE PRINCIPAL INVESTIGATOR PROGRAMS

Single ARL principal investigators from HBCUs/MIs can significantly enhance the research mission of their institutions. Successful single-PI efforts—those that result in peer judgment of high-quality research—facilitate the identification of scientific leadership, scientific entrepreneurial talent, and inspirational skills that are critically needed at all institutions of higher learning. Single-PI projects facilitate, enhance, promote, and support interactions between students and researchers; this is a very successful model of mentorship in STEM. ARL has used roughly two-thirds of its HBCU/MI funding to support single-PI efforts.

A recent article2 observed that

College graduates had double the odds of being engaged at work and three times the odds of thriving in Gallup’s five elements of well-being if they had had ‘emotional support’—professors who ‘made [them] excited about learning,’ ‘cared about [them] as a person,’ or ‘encouraged [their] hopes and dreams.’ Graduates who had done a long-term project that took a semester or more, who had held an internship, or who were extremely involved in extracurricular activities or organizations had twice the odds of being engaged at work and an edge in thriving in well-being.

_________________

1Army Research Laboratory, “HBCU/MI,” http://www.arl.army.mil/www/pages/9, accessed May 25, 2014.

2Scott Carlson, “A Caring Professor May Be Key in How a Graduate Thrives,” Chronicle of Higher Education, May 6, 2014, http://chronicle.com/article/A-Caring-Professor-May-BeKey/146409/?cid=at&utmsource=at&utmmedium=en.

The impact that HBCUs/MIs are having in training the next generation of STEM Ph.D.’s relies on the fact that students attending these institutions have access to cutting-edge research. ARL single-PI funding not only brings research of interest to the Army into HBCUs and MIs but also, by putting funds in the hands of single PIs, reinforces the value, importance, and impact of individualized mentorship models. Single-PI ARL funding has increased the capacity for providing research opportunities at HBCU/MI institutions, naturally benefitting URMs.

The ARL resources provided to successful researchers—those who achieve peer judgment of high-quality research—have a direct impact on PI research programs, contributing to the development of the scientific workforce by offering training opportunities from the undergraduate to the postdoctoral level. Successful single PIs are entrepreneurs, aggressively searching for resources to carry out research programs that create new knowledge, enhancing the research capacity of the institution. Successful PIs were identified at all the institutions with which the committee engaged in discussion.

Navigating through the ARL funding process does not appear to be straightforward. PIs with prior knowledge of the culture of ARL and familiarity with the outreach efforts of specific ARL program directors became ideal mentors of early-career researchers looking for ARL funding. The lack of synchrony between the time to a Ph.D. and the duration of the funding (3 years) can limit the ability of HBCUs/MIs to support Ph.D. candidates.

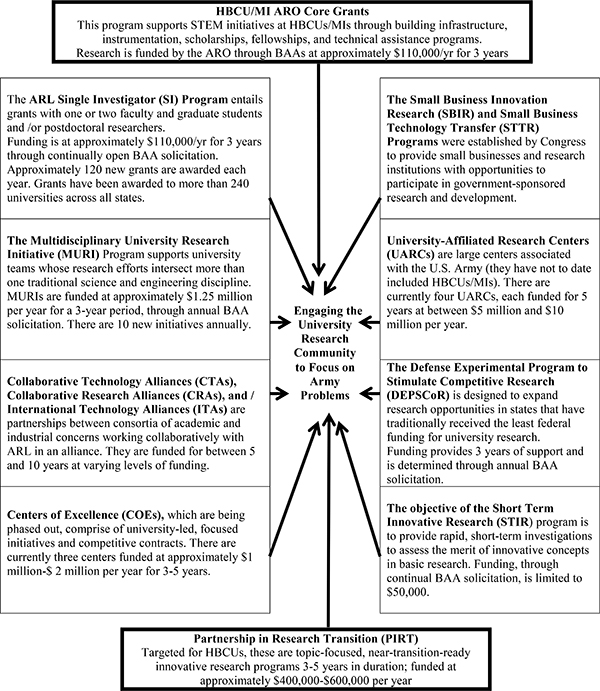

ARL is engaged in a variety of agreements with HBCUs and MIs that provide opportunities to participate in Defense research programs. The ARL funds STEM research programs at the institutions, STEM programs for students, and programs and opportunities for faculty and staff to interact with ARL scientists and engineers, to access scientific and technical information, and to collaborate with other educational institutions or research facilities such as the DoD laboratories. ARL programs are highlighted in Figure 5.1 and described in Appendix B. Of note, only two programs focus specifically on HBCU/MI support: HBCU/MI ARO Core Grants and the Partnership in Research Transition (PIRT), though support may also be provided through the other ARL programs.

RECONSIDERING THE BALANCE BETWEEN COLLABORATIVE PROGRAMS AND SINGLE-PI PROGRAMS

The ratio of number of grants to number of collaborative programs is high, averaging 87 percent to 13 percent over the past decade (see Table 5.1); in terms of real dollars, the ratio is lower—approximately 2 to 1 (see Table 5.2). Collaborative programs have received nearly 33 percent of the funds allocated to HBCUs/MIs over the past 10 years.

Collaborative Programs Foster Institution Building

As noted in Chapter 4, the discussions with representatives of HBCUs/MIs confirmed that all sources of money, whether grants or cooperative agreements, have immediate positive impacts, assisting students, enabling research by faculty and students, stimulating new and enhanced course offerings, and setting the stage for further funding by ARL and/or other agencies. Many of the administrators and faculty members interviewed suggested that cooperative/collaborative programs with ARL are more effective than single-PI grants or contracts in achieving the objective of institution building, provided that the cooperative/collaborative programs are properly managed.

FIGURE 5.1 ARL programs that engage the university research community to focus on Army problems. (Based on a chart presented to the committee by the manager of the ARL Outreach Office.) HBCU/MI ARO core grants and PIRT programs specifically target HBCUs/MIs, although other programs may also involve HBCUs/MIs.

TABLE 5.1 Number and Share of Grants and of Cooperative Agreements

|

|

||||

| Year | Number of Grants | Number of Cooperative Agreements | Percentage of Grants | Percentage of Cooperative Agreements |

|

|

||||

| 2004 | 98 | 13 | 88 | 12 |

| 2005 | 114 | 17 | 88 | 12 |

| 2006 | 128 | 20 | 84 | 16 |

| 2007 | 126 | 18 | 86 | 14 |

| 2008 | 121 | 17 | 86 | 14 |

| 2009 | 83 | 9 | 89 | 11 |

| 2010 | 106 | 3 | 97 | 3 |

| 2011 | 90 | 9 | 90 | 10 |

| 2012 | 116 | 17 | 85 | 15 |

| 2013 | 90 | 18 | 80 | 20 |

| Total/Average | 1,093 | 141 | 87 | 13 |

|

|

||||

TABLE 5.2 Comparison of Funds for Grants and Funds for Cooperative Agreements

|

|

||

| Year | Grants (%) | Cooperative Agreements (%) |

|

|

||

| 2004 | 76 | 24 |

| 2005 | 76 | 24 |

| 2006 | 58 | 42 |

| 2007 | 53 | 47 |

| 2008 | 51 | 49 |

| 2009 | 69 | 31 |

| 2010 | 84 | 16 |

| 2011 | 61 | 39 |

| 2012 | 67 | 33 |

| 2013 | 70 | 30 |

| Average | 67 | 33 |

|

|

||

The interviewees suggested that cooperative/collaborative programs are more effective because they

• Permit more extensive person-to-person interactions, which are more valuable in the long term for the students, faculty, and institutions.

• Facilitate the mentoring of fledgling institutions by more experienced HBCUs/MIs. A novice institution would benefit from securing collaborative projects funding with colleagues in

other more established research institutions that could add fuel to propel the capacity building of the institution.

• Enhance continuity. A 3-year grant can be an important part of a large, ongoing program, but a single-PI grant is not enough by itself to develop a program. If a grant is not renewed, the resulting disruption may require the investigator to start a new funding process.

• May help institutions in building their desired infrastructure and institutional base.

• Enhance the stability of an institution’s research programs, reduce the uncertainty of graduate student participation, and provide better research refocus at the institutions.

• Represent a more strategic approach to identify and reinforce the already growing centers of excellence at some HBCUs, building on their strengths.

The following factors were suggested by the interviewees with respect to the need for proactive management of cooperative/collaborative programs:

• When HBCU/MI involvement in programs is mandated, or when their participation is invited as an afterthought by the prime contractors, the HBCUs/MIs may not be given adequate consideration during program planning and development. For example, a prime contractor may organize a proposal and then identify the HBCU that “fits” the already written proposal. In such a case, little may be expected from the HBCU/MI participants, and little effort may be expended by either the prime or ARL program managers to draw upon the full capabilities of the HBCU/MI participants.

• In multiperformer projects, participating HBCUs/MIs often receive a much smaller portion of the project tasking than their non-HBCU/MI collaborators and much less research funding and support dollars. In some cases, lead non-HBCU/MI institutions may bring HBCU/MI students to the lead institution as research participants; this will benefit these students, but it will have no lasting impact on the HBCU/MI faculty, infrastructure, or reputation.

• HBCUs/MIs sometimes feel that they are not participants in the critical decision-making paths of consortia and that their science and technology (S&T) capabilities are not adequately utilized by the prime contractors.

• As regards UARC participation, HBCU/MI funding is not substantial enough to create the strong and sustaining foundation needed to compete successfully for UARC projects year after year without ARL mentoring and interaction.

• Without diligent management by ARL, program leaders may reallocate funding originally slated for HBCU/MI participants.

HBCU/MI faculty and administrators interviewed were consistent in suggesting that spreading limited funds across a large number of individual PIs and numerous HBCU/MI institutions provides positive short-term benefits to faculty and the students but fails to consider the long-term development of institutional capability.

Acknowledging that most HBCUs/MIs would not be where they are without grant programs like those funded by ARL, the HBCUs/MIs may be at an inflection point where revisiting the ratio of single-PI grants to collaborative programs is warranted, with an eye toward institution building. Increasing the allocation of funds to cooperative/collaborative programs with significant HBCU/MI participation could encourage the institutions to generate better strategic plans for growing their capabilities and for serving their student population.

Considering the Impact of Funding Approaches

ARL needs a strategic plan for the allocation of funds to HBCUs/MIs that includes assessment of the impact of the funds in terms of HBCU/MI program goals set by ARL (including, possibly, the goal of institution building) at those institutions and that applies the assessment to appropriately balance single-PI grants and collaborative/cooperative programs. Depending on how ARL decides to allocate funding to experienced, highly successful HBCUs/MIs, helping them to progress to the point at which they do not depend on such support, and to fledgling HBCUs/MIs, helping them to begin institution building, rebalancing will have to be slowly orchestrated.

Historically, as indicated in Table 5.3, over the past 10 years approximately 74.2 percent of the dollars and 70.9 percent of the cooperative agreements went to four institutions. The implication is that some HBCUs/MIs could mentor others on how to develop a productive, institution-building relationship with ARL. ARL could also learn from the successful HBCUs/MIs the success strategies that they have developed.

TABLE 5.3 Cooperative Agreements at 14 HBCUs/MIs

|

|

||

| HBCU/MI | Share of Total HBCU/MI Funding (%) | Share by Number of Agreements (%) |

|

|

||

| New Mexico State University | 46.8 | 28.37 |

| North Carolina A&T State University | 15.0 | 24.11 |

| Howard University | 8.4 | 11.35 |

| Tennessee State University | 4.0 | 7.09 |

| Subtotal | 74.2 | 70.90 |

| Tuskegee University | 4.8 | 6.38 |

| Hampton University | 4.3 | 4.96 |

| Prairie View A&M Research Foundation | 3.8 | 4.96 |

| Florida A&M University | 5.7 | 2.84 |

| Morgan State University | 0.4 | 2.84 |

| Clark Atlanta University | 0.5 | 1.42 |

| Lincoln University at Jefferson City | 2.4 | 1.42 |

| City College of New York, Queens College | 0.1 | 1.42 |

| University of Puerto Rico at Mayaguez | 0.1 | 1.42 |

| Total | 100.0 | 100.00 |

|

|

||

TABLE 5.4 HBCU/MI Shares of Total ARL Funding for Single PIs (percent)

|

|

||

| Dollar Amount of Grants | Number of Grants | |

|

|

||

| University of California, Riverside | 6.6 | 10.0 |

| University of New Mexico, Albuquerque | 9.8 | 9.7 |

| University of California, Berkeley | 23.5 | 8.8 |

| University of California, Los Angeles | 5.9 | 8.2 |

| North Carolina A&T State University | 6.5 | 6.2 |

| University of Puerto Rico at Mayaguez | 7.2 | 6.2 |

| City College of New York | 2.9 | 5.0 |

| Howard University | 2.2 | 4.1 |

| University of California, Irvine | 2.5 | 3.8 |

| Florida A&M University | 1.9 | 3.3 |

| City College of New York (Flushing) | 1.6 | 2.9 |

| University of Texas at San Antonio | 1.7 | 2.6 |

| Total | 72.3 | 70.8 |

|

|

||

As indicated in Table 5.4, several institutions are very experienced in securing single-PI grants. These institutions appear to have learned well the proposal development process and have overcome administrative roadblocks, so they might be good mentors for fledgling institutions.

It is necessary for ARL to be proactive in securing the significant participation of HBCUs/MIs in multiyear cooperative agreements to ensure that these institutions have adequate funding and time to gain access to and procure equipment, support the completion of graduate student research, arrange for onsite or virtual internships with ARL laboratories or other laboratories, and develop the capacity to respond to ARL programmatic redirection of funded research tasks. As part of a proactive strategy, it is important that ARL consider the following:

• Communicating a strategic vision for the program that aims to enhance the science and engineering education beyond just funding (e.g., internships, symposia),

• Assisting in mentoring the HBCU/MI candidates responding to the BAA and executing tasks after award,

• Reviewing its core and cooperative agreement BAA processes to minimize administrative burdens on HBCU/MI respondents.

• Developing metrics of performance to measure contract performance,

• Developing metrics for the impacts of the funding on the institution building of the recipients,

• Ensuring meaningful participation of fledgling HBCUs/MIs, and

• Assisting successful institutions to progress to a level of institution building that allows them to compete on an even footing with other research institutions.