4

Innovative Strategies and Opportunities

Several presentations and discussions on innovative strategies focused on system-level levers and blockages in funding implementation of evidence-based preventive interventions for children and on new business models. These strategies include forging public–private partnerships and applying new or underused funding provided by various divisions of the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), as well as ways to build consumer demand for evidence-based interventions (EBIs).

ADDRESSING BARRIERS WITH NEW BUSINESS MODELS AND FUNDING MECHANISMS

Kelly Kelleher began his presentation by noting that a major barrier to broad-based implementation of EBIs is a lack of sustainable funding for them, particularly those that rely on government funding, because when the grant funding runs out or the government changes, the funding disappears, he noted. “I’ve spent many years trying to implement prevention programs, and I have become convinced that in our current medical system, the only thing that really matters is does it [the intervention] get paid for, because our system figures out what to do about all the other issues,” he said.

Kelleher pointed out that prevention initiatives are often not reimbursed because they usually do not occur in medical settings, frequently use unlicensed professionals, or offer group interventions, for which it is difficult to bill an insurer. Grants often do not cover the expense of professional development and infrastructure, he added, and regulatory or legislative mandates are often too specific for prevention initiatives, requiring piecing

together several funding sources that have to be continually renewed and that change as governments change.

Public–Private Partnerships

An innovative way to support a prevention initiative is to create a sustainable business model that is based on a shared value between a business and a social agency, such that their partnership can carry out a social good while simultaneously offering a sustainable business opportunity, Kelleher said. These partnerships require clear outcomes that can be measured, intensive data collection, and alignment of incentives for both the business partner and the social good, Kelleher noted.

Partners for Kids

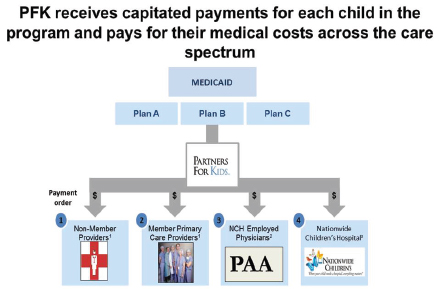

Kelleher reported on a public–private partnership he is involved with in Columbus, Ohio, called Partners for Kids (PFK). This partnership between Nationwide Children’s Hospital and 800 physicians was formed 10 years ago as an intermediary insurance organization and is now an accountable care organization. The Ohio Department of Medicaid contracts with five Medicaid managed care organizations, which deduct an administrative fee and pass all the remaining resources to PFK. PFK then uses these capitated payments for the 300,000 children in the program to pay for their medical costs across the health spectrum.

It took a concerted effort involving many meetings with the governor of Ohio, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), and diverse hospitals and provider groups that supported the program to forge this public–private partnership and have one accountable payer for all children’s services in 34 rural and urban counties in central and southeastern Ohio, Kelleher noted (see Figure 4-1). What aided the partnership’s implementation was the recognition that “kids were different and that pediatric exclusivity was really of value to the state Medicaid director, who was a pediatrician,” Kelleher said.

A major expense for PFK was the cost of behavioral health drugs, which made up one-third of all the pharmacy costs for the children PFK covered, many of whom came from inner-city, low-income areas and were being treated in emergency rooms. To reduce the costs of treating such children for behavioral problems, PFK focused on preventing problems with such EBIs as the Good Behavior Game, The Incredible Years®, Safer Choices, and home visiting with the Supporting Partnerships to Assure Ready Kids (SPARK).

“The physician–hospital organization has committed to introducing these programs because the long-term growth and health of the community

FIGURE 4-1 Funds flow in Partners for Kids contracting.

NOTE: NCH = National Children’s Hospital; PAA = Pediatric Academic Association.

SOURCE: Kelleher, 2014.

are critically important,” Kelleher said. Children’s hospitals in close to 10 states have also developed partnerships similar to PFK, and about half of these provide prevention initiatives targeting the neighborhoods that could most benefit from having them. “It’s not unique to Columbus, but it’s actually the beginning of something that hospitals are understanding—it’s not only an ethical mandate, but a business mandate,” Kelleher said.

PFK is also part of a pay-for-outcomes business plan for an alliance of rural agencies in southeastern Ohio that serve Appalachian children. PFK and Nationwide Children’s Hospital pay social service agencies that are part of the alliance a flat fee every time they enroll a child in Medicaid. But the social service agencies receive additional fees for providing beneficial yet cost-saving services and outcomes for their members, such as providing their clients with a long-acting, reversible contraceptive or early prenatal care that results in the birth of a healthy baby. The agencies also receive an additional fee if one of their teenagers participates in the Safer Choices program and graduates from high school.

For its operations, PFK collected abundant data on its clients on a regular basis, including claims data that indicated costs, patient locations, and eligibility. In addition, the organization uses electronic health records to

find children at risk who are starting to show patterns of concern, including those being admitted to the emergency room frequently for minor trauma. In addition, although PFK provides no obstetric care, it built a database registry for all prenatal providers in its system to enter their progesterone doses for women with prior preterm births and immunizations and long-acting contraceptive data into a system that could serve as a common community platform that PFK analyzed for quality of care. For a selected subset of clients, such as children with gastric feeding tubes, PFK administered surveys to their families to assess activities of daily living scales and satisfaction in an effort to monitor and change practice.

Social Accountable Care Organizations and Social Impact Bonds

Social accountable care organizations, also called total accountable care organizations, are an extension of the accountable care organization concept and address social and human service concerns in addition to physical health concerns. Public health advocates have argued that many determinants of health are social and that to address them adequately requires social and human service interventions, Kelleher noted. These organizations not only provide medical care for their clients, but they are also partnering with state agencies to provide school-based mental health, juvenile justice, and foster care services in their early forms.

Richard Frank reported on social impact bonds, also known as pay-for-success bonds. These bonds are a new idea that originated in the criminal justice arena in the United Kingdom. For the past three budget cycles, President Obama has proposed about $100 million per year in social impact bonds, although only a starter fund of $10 million to $20 million per year was actually budgeted for these initiatives that have come out of the Departments of Justice and Labor and are just starting to emerge in HHS.

Social impact bonds are issued by the federal, state, or local government and offer participating investors payouts based on the achievement of program outcomes, which are monitored by the private sector. The private up-front money relieves public budgets and shifts the risk of investment in programs from the government to the private sector. If the program that is supported is successful, the private investors receive from the government their original investment plus a rate of return above that, based on the achievement of particular outcomes that are socially desirable. In addition to the outcomes they aim to achieve, typically social impact bonds result in savings of public monies, Frank pointed out, and are currently being used to support nurse home visitation, targeted prekindergarten, and child abuse and neglect prevention programs.

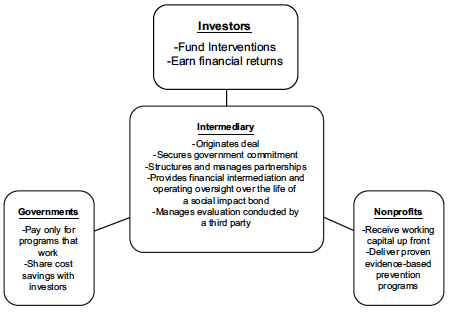

Social impact bonds usually involve four parties: investors, an intermediary, government, and nonprofits. The investors fund interventions and

earn financial returns on them. Frank noted that investors also serve as evaluators of a program’s feasibility as part of the vetting of the investment they make, which adds another level of accountability. The government pays only for programs that work and shares its cost savings with investors. Usually an intermediary organization, which originates the deal, secures government commitment and structures and manages the partnership. This organization provides financial intermediation and operating oversight over the life of a social impact bond and manages the evaluation of outcomes conducted by a third party. Nonprofits provide the actual services after receiving working capital up front (see Figure 4-2).

Social impact bonds create new sources of funding for prevention initiatives and are popular among politicians because the government only pays for programs shown to work, Frank noted. Social impact bonds are also attractive to investors because there are tax rules that provide incentives for these types of investments.

Frank added that one downside of this business model is that many valuable public programs do not generate savings quickly. For example,

FIGURE 4-2 Social impact bonds.

NOTE: “Social impact bonds” refers to a new and innovative financing vehicle for

social programs in which government agencies define desired outcomes and provide

payment to external organizations that achieve those outcomes.

SOURCE: Frank, 2014.

in nurse home visitation programs, in which nurses make home visits to pregnant women on Medicaid and for the first 2 years following birth of their children, many benefits, such as reduced rates of juvenile delinquency and drug use in mothers’ children once they become teenagers, are not accrued until several years after women start participating in the program. However, indicators of strong progress can be used for those programs with long-term payoffs, Frank said, with payments to investors tied to reaching certain milestones. He added that juvenile justice payoffs tend to occur quickly, and New York City has social impact bonds funding one of their programs in this sector.

Later during discussion, David Brent added that behavioral health interventions can have an impact on physical health, so their payoff can be determined by proximal measures that are more accepted and already in use, such as maternal depression, pediatric asthma, and emergency room visits. He also pointed out that social impact bonds can be bundled such that there is a mixture of short- and long-term payoffs that makes them more attractive to investors. Frank concurred that bundling of social impact bonds is a good idea. He noted, however, that when one carefully analyzes health care outcome effects of preventive mental health services, social impact bonds only work for a small slice of the population. To make this argument, Frank said, requires targeting programs to that group with the aim of making clinical advances, but not necessarily public health advances.

Frank added that social impact bonds also can be risky investments that make them unappealing to some investors, although there is potential to make them more attractive if foundations are willing to take on some of the risk. The ultimate effectiveness of social impact bonds as a means to support prevention programs is not yet known, Frank noted, because they are in the early stages of development.

In their breakout session summary, members of the child welfare and juvenile/family justice group expressed interest in public–private partnerships, such as those between the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and community groups and those created by partnering with private investors. Members of the group discussed the necessity of developing a venture capital model that will appeal to community-based private investors.

Health and Human Services Funding

Some presenters and workshop participants reported on new or underused HHS funding sources for prevention EBIs, including medical waivers and new opportunities offered under the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) and mental health parity legislation. Bryan Samuels noted that Title IV-E of the Social Security Act enables the Child Welfare Waiver

Demonstration authority to provide states with an opportunity to use federal funds more flexibly in order to test innovative approaches to child welfare service delivery and financing. Using this option, states can design and demonstrate a wide range of approaches to reforming child welfare and improving outcomes in the areas of safety, permanency, and well-being (HHS, 2014).

Samuels pointed out that Title IV-E is the largest funding source that goes to state child welfare agencies to support out-of-home care for children. This federal waiver allows states the flexibility to use federal funding not only for children who are in care, but also for children before and after they come into such care to ensure adequate continuity of care. Samuels reported that about 20 states are currently applying these waivers to learn how to implement EBIs at the state welfare agency level as well as to assess their effectiveness at the child and family level. HHS has the authority to grant waivers to 10 more states, he added.

Another source of funding for prevention EBIs are Medicaid waivers. Eric Bruns noted that as a means for decreasing Medicaid expenditures for costly residential and psychiatric in-patient care, some states are applying more of their Medicaid funds to invest upstream in prevention and early intervention programs. “We need to find ways to encourage states to maximize the options available to them in Medicaid,” Bruns said, and suggested Medicaid funds be used to cover a broader array of behavioral health home- and community-based services and intensive care coordination using multimodal EBIs.

Hendricks Brown suggested broadening the use of waivers beyond Medicaid and also considering using waivers from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) as well as from across sectors, including a combination of state funds allocated for education, juvenile justice, and child welfare programs. Director Frances Harding added that SAMHSA provides block grant funding for substance abuse and 20 percent of that fund is earmarked for primary prevention. SAMHSA has a discretionary portfolio, she said, under which communities or states could be funded to do screening for maltreatment as a way to help prevent mental and substance abuse disorders, if their data point to this need.

Lauren Supplee, Office of the Administration for Children and Families, reported that in the federal appropriations bill for fiscal year 2014, funding was allocated for Performance Partnership pilots, which are waivers for up to 10 communities to focus on improving outcomes in young people age 14 to 24 who are homeless, in foster care, involved in the justice system, or not working or not enrolled in (or at risk of dropping out of) an educational institution (Department of Education, 2014). Performance Partnership pilots will allow a state, region, locality, or federally recognized tribe to propose pooling a portion of discretionary funds they receive under mul-

tiple federal streams while measuring and tracking specific cross-program outcomes. Supplee said that this model for pooling funds, combined with strengthened accountability for results, is designed to ease administrative burden and promote better education, employment, and other key outcomes for youth.

The Performance Pilots initiative, which is spearheaded by the Obama administration, does not provide additional funds, but rather enables more flexible use of existing funds (Department of Education, 2014). There will be waivers for education, labor, child welfare, SAMHSA, runaway and homeless youth, and other programs, according to Supplee. CMS may not necessarily be a source for the waivers in this program, she added. But members in the health care breakout group suggested considering waivers and other payment flexibilities for the funds CMS provides that could be used to support prevention programs.

Frank reported that the Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act (MHPAEA) of 2008 requires group health plans and health insurance issuers to ensure that financial requirements (such as co-pays, deductibles) and treatment limitations (such as visit limits) applicable to mental health or substance use disorder benefits are no more restrictive than the predominant requirements or limitations applied to substantially all medical/ surgical benefits (CMS, 2014). The law is limited to firms that offer mental health benefits as part of their coverage and to firms with 50 or more employees.

Frank also noted that the ACA, which was signed into law in 2010, further expands coverage for behavioral health services by establishing mental health and substance abuse benefits as essential health benefits that must be offered at parity to other health benefits in qualified health plans, just as they are for health insurance issuers and group health plans. It has been estimated that the ACA will newly insure about 30 million people (CBO, 2012), thus improving access to mental and behavioral health services and substance abuse treatment for many people.

The ACA also established a Prevention and Public Health Fund that can be tapped for prevention initiatives for children. In addition, the ACA supports innovative delivery systems for health care including accountable care organizations, Medicaid Health Homes, and patient-centered medical homes. These new health care systems are designed to shift the emphasis away from fee-for-service, insurance-based designs to more budgeted systems that still have an insurance component but are run by clinical organizations, Frank reported. This provides economic incentives to save money with prevention and early intervention programs, especially for clinical preventive services. “In theory, you would expect these new organizations to use that flexibility to invest in preventive services because they pay off, according to some evidence,” he said.

But the challenge will be providing the appropriate outcome measures that ensure quality clinical standards are being met, which is a stipulation for receiving funding from the ACA. The standards for behavioral health, Frank noted, are still in their infancy. In addition, measures of behavioral health have to be correlated to other clinical health measures, such as cardiovascular or pediatric, because of the growing emphasis on integrating behavioral health with physical health.

The ACA funding also cannot be used to support large-scale public health measures, which tie into social welfare, housing, and juvenile justice, Frank noted. “The incentives to do that are much weaker under these new organizations because you’re asking people not only to use dollars that are based on health care accounting, but you’re asking them to go way beyond their traditional areas of expertise and areas of touch,” Frank said.

The ACA expanded federal community benefit requirements for nonprofit hospitals by creating new standards relating to the conduct of needs assessments whereby nonprofit hospitals, in consultation with the communities where they are located, identify the communities’ health-related needs. Several participants in the schools breakout session suggested exploring whether the needs assessment could be used to support design and implementation of prevention programs in schools.

In one discussion session, a participant suggested manipulating CMS billing codes so providers may be reimbursed for early interventions for children who have experienced psychological trauma but who do not have a diagnosis of posttraumatic stress disorder. Such children tend to have other conditions for which CMS will reimburse care, he noted. “We can use less specific diagnoses sometimes for something more specific and get paid for it,” he said. Samuels responded that the federal standard for treatment is medical necessity, which states tend to define as having a diagnosis. So in theory, based on the federal standard of medical necessity, one could get reimbursed for treating a child who has experienced trauma, but state law would not allow this. If one tries to bypass the need for a posttraumatic stress syndrome diagnosis by treating for another frequently related diagnosis, he added, then one is subjected to the specific treatment protocols for the other diagnosis such that the child is probably not getting the care they need for their trauma, Samuels said.

Chambers reported that several members of the health care breakout group discussed the need to make a business case for prevention programs and that effort should be made to tailor those programs so they fit existing funding streams. They also discussed how multiple funding sources are often needed to cover the services as well as build the workforce needed to carry out those services.

BUILDING DISSEMINATION AND UTILIZATION OF EVIDENCE-BASED INTERVENTIONS

Several workshop attendees emphasized the need to build consumer demand for EBIs by assessing and responding to community needs and by marketing the likely impact of the EBIs employed. A menu of EBIs should be offered from which communities can choose, suggested Charles Collins as well as members of the health care breakout group, and multiple EBIs may have to be used to meet a community’s needs, Bruns noted. “We need to overcome some of our potentially outdated concepts about implementation of frameworks that are only geared to scaling up one EBI in the system, when we know we’ll probably need multiple EBIs to cover all the needs of a population,” he said.

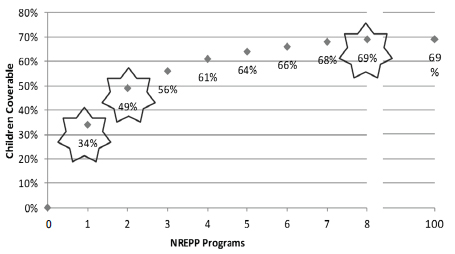

Bruce Chorpita noted that when he simulated enrolling approximately 2,000 youth matched for age, gender, and presenting problem from the Hawaii state mental health system into randomized trials to determine the best-fitting EBIs, the most relevant evidence-based program would serve only 34 percent of those youth. Adding an additional EBI would serve 49 percent, with additional benefits accrued by adding more interventions up to a maximum of 69 percent reached when eight different EBIs were used. Beyond eight, additional EBIs would not serve any additional youth in the system. Chorpita emphasized that “the bottom line is EBIs may not be sufficient to create high-performance systems because about a third of the cases are exceptions for which there are no matching EBIs available in the literature” (see Figure 4-3).

In addition, he found that although Los Angeles County mandates using EBIs with its prevention and early intervention programs, 39 percent of the cases he reviewed did not use an EBI. When EBIs were used, they did not match any of the youth’s top three concerns in 32 percent of those cases, so only about one-quarter of the youths in the system were getting an appropriate EBI. This study found that the biggest predictor of what providers deliver is whatever program they were trained to use, rather than characteristics of the youth. Furthermore, 94 percent of the time that providers delivered trauma-focused care, it did not match any of the child’s top three concerns. So although there was great dissemination of EBIs in Los Angeles County, “they did not help the children with the problems for which they were seeking help,” Chorpita said. He suggested not only matching EBIs better to the children who need them, but also being dynamic about assessing and adjusting those that are applied with a strategy he developed called Managing and Adapting Practice (MAP), which is described in Chapter 2.

Collins noted the tension that often occurs between adaptation of EBIs when they are used in real-world settings and the fidelity required in order

FIGURE 4-3 Matching youth to studies on problems, age, and gender.

NOTE: NREPP refers to the National Registry of Evidence-based Programs and Practices.

SOURCE: Bernstein et al., 2010.

to have the same results seen in academic studies. “Adaptation tends to be a secondary thought for many researchers, but it’s the exact reverse when you’re dealing with communities,” who have to adapt the intervention so it better meets the needs of clients and the staff running the programs, he said. He cautioned that such adaptation should be encouraged and not frowned upon because “adaptation is necessary for ownership, which is necessary for sustainability. Rather than adaptation being a frightening word, it needs to serve as a stimulus for your dialogue with your providers to begin to move toward fidelity.” If a community is only carrying out half of a program, instead of viewing them as being half non-compliant, he suggested, consider that “they’re halfway there, and see how you can move them further.”

Collins views implementation of interventions as a blending of behavioral science with local knowledge and suggests that materials be flexible and rewritten based on the experiences learned from consumers. He suggested assessing why some interventions are not selected and implemented by consumers and whether the staff leaves the training provided with the skills and materials to actually implement the intervention. He noted that communities frequently will indicate what interventions are not appropriate for them, and those programs should be dropped. He added that if different

communities applying the intervention are achieving different outcomes, then assess if there are any implementation clues as to why one program is having better outcomes than another. “I think you have to think about the whole process step by step in terms of corrections to your system,” Collins said.

Participants in the health care breakout group concurred that it is important to understand local community needs and how to meet them. Program delivery should be guided based on data collected from consumers. Members of the group noted it may be more appropriate to follow evidence-informed core principles than to have “manualized” delivery of EBIs. Collins noted that communities tend to need a packaged intervention that details how to recruit the target audience and that provides other concrete steps, including detailed lesson plans, whereas physicians or academic partners may just need principles as opposed to packaged interventions. Some members of the health care breakout group also suggested engaging communities better so there is more community ownership of different interventions and marketing the impact of prevention to both consumers and funders using a range of mechanisms, including op-eds in local newspapers and reports in scientific journals.

Based on the experience CDC had in disseminating HIV prevention programs, Collins suggested using a range of dissemination partners and adjusting the intervention to the capacity of the disseminating organization. He noted that “different partners have different tentacles reaching into different organizations” and that CDC chose the appropriate range of partners as part of its dissemination strategy. He added that CDC tries to include the original researcher of an EBI on the dissemination team if that researcher is interested in being a dissemination partner with CDC. However, not all researchers want to be involved in this way.

CDC also tries to balance community-developed interventions with academic ones. About 20 percent of the programs it disseminated and funded as part of the HIV prevention initiative were community developed, Collins reported. When CDC learned of a program that was developed in the community and saw that it had good process data and a logical model and was starting to do pre- and postintervention tests on clients that revealed changes, it gave the program an extra $100,000 for 2 years and then tested its outcomes, Collins said. This led to CDC discovering and more widely disseminating interventions developed by community practitioners. However, Collins cautioned that there must be good process measures, outcome monitoring, and consistent delivery of community-developed interventions before considering an intervention’s adoption and dissemination.

Participants in the schools breakout group had a few suggestions for improving the uptake of EBIs in the school system, including emphasizing common shared goals and marketing prevention EBIs as able to meet the

needs of not just students, but teachers and school administrators, while making their jobs easier rather than more burdensome. These participants also suggested using easily understood terms and familiar goals, such as the Common Core State Standards Initiative goals,1 when conveying to schools that the social, emotional, and family supports that EBIs provide for children are needed for their students’ academic achievement.

Having a system of common metrics for those goals that are publicly reported for schools could serve as a lever to get EBI adoption in schools, one participant noted. Alternatively, such metrics could be tied to school funding such that schools are rewarded financially when their students have better outcomes. Either way, the metrics will motivate teachers and school administrators to do proactive planning with those objectives in mind. For example, many schools receive more funding if they have greater student attendance, so an EBI that has been shown to boost school attendance could be marketed to schools as a way to increase their budgets, one participant noted.

Members from both the schools and the child welfare and juvenile/ family justice breakout groups suggested establishing a clearinghouse for which EBIs have worked and where, including information on how to fund them, as well as EBIs that have failed when implemented in certain settings. Collins emphasized that “negative findings are very important for being able to change direction and determine how you might work in a different way.” Lastly, Bruns suggested that state centers of excellence be established for prevention EBIs.

Bernstein, A. D., B. F. Chorpita, and E. L. Daleiden. 2010. Mapping the relevance of evidence-based treatments to real service populations. Symposium presented at the 44th annual convention of the Association for Behavioral and Cognitive Therapies, San Francisco, CA.

CBO (Congressional Budget Office). 2012. Updated estimates for the insurance coverage provisions of the Affordable Care Act. http://www.cbo.gov/sites/default/files/cbofiles/attachments/03-13-Coverage%20Estimates.pdf (accessed September 8, 2014).

CMS (Centers for Medicaid & Medicare Services). 2014. The Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act. http://www.cms.gov/CCIIO/Programs-and-Initiatives/Other-InsuranceProtections/mhpaea_factsheet.html (accessed September 8, 2014).

Common Core. 2014. About the standards. http://www.corestandards.org/about-the-standards (accessed September 3, 2014).

Department of Education. 2014. Performance partnerships for disconnected youth. http://www.ed.gov/blog/wp-content/uploads/2014/03/2014-PPPs-Fact-Sheet.pdf (accessed August 11, 2014).

__________________

1The Common Core State Standards Initiative sets academic standards in mathematics and English language arts/literacy and outlines what a student should know and be able to do at the end of each grade (Common Core, 2014).

Frank, R. G. 2014. Economics, policy and scaling interventions for children’s behavioral health. Presented at IOM and NRC Workshop on Harvesting the Scientific Investment in Prevention Science to Promote Children’s Cognitive, Affective, and Behavioral Health, Washington, DC.

HHS (Department of Health and Human Services). 2014. Child welfare waivers. http://www.acf.hhs.gov/programs/cb/programs/child-welfare-waivers (accessed August 11, 2014).

Kelleher, K. J. 2014. Prevention does not scale/sustain: Lack of payment. Presented at IOM and NRC Workshop on Harvesting the Scientific Investment in Prevention Science to Promote Children’s Cognitive, Affective, and Behavioral Health, Washington, DC.