Coordinating Logistics to Execute Rapid Research in Disaster Response

This section focuses on the logistics of rapid research in a disaster, with discussions facilitated by Howard Zucker, acting commissioner of health for the state of New York. Participants discussed triggers for go/no-go scenarios, just-in-time training for research responders, integration of disaster research response into the ICS, and corresponding logistical needs when working in disaster settings.

INTEGRATING DISASTER RESEARCH INTO THE INCIDENT COMMAND STRUCTURE

From a state and local agency perspective, disaster research should inform or enhance emergency response or recovery activities, said Shelley DuTeaux, the assistant deputy director for public health and emergency preparedness for the California Department of Public Health. All disasters are local, she said, whether the locality is a neighborhood, a city or county, or multiple cities or counties. In a disaster, if localities lack or have exhausted their resources and capabilities, they will request assistance from a county or regional level. If they cannot assist, the request elevates to the state level (or state-to-state mutual aid through agreements such as an Emergency Management Assistance Compact) and then to the federal level.

Each state should have an ICS, which is a tool for coordinating resources and communication during an emergency. The ICS is integrated throughout the emergency management structure. All response and recovery activities (federal, state, mutual aid) are done in support of the local activities, and activities should integrate into the emergency management structure that is already in place. In this regard, anyone who brings research

resources to the field needs to know and integrate into the emergency management structure, DuTeaux said. She recommended that researchers planning to go in the field get basic training on the ICS so they know where they fit into the emergency operations structure and do not hinder the response.1 In particular, in the ICS there is an incident safety officer who is responsible for the safety of everyone in the field, and researchers should make their presence in the field known to the safety officer.

All states have different thresholds and capacity at which they may request federal assistance. Requests may be made in the case of a presidential declaration of emergency (a Stafford Act declaration authorizing the delivery of federal technical, financial, logistical, and other assistance during a declared disaster or emergency). Federal assistance, coordinated by FEMA, is provided if the governor certifies that the event exceeds the combined response capabilities of the state and local governments. DuTeaux pointed out that the presidential emergency declaration specifies the type of assistance authorized, and therefore, for assistance for disaster research to be authorized, it must be in the emergency declaration.

If there is no presidential declaration, access to federal assistance can still be given directly through the appropriate agency if that agency has the authority to act and to expend its own resources. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), for example, can act on its own authority with its own money to help states in the absence of a presidential declaration. DuTeaux noted that in the midst of an emergency, the state might not know what federal resources are available to it. It would help, she suggested, if federal partners would “lean forward” and suggest the kind of help they can provide.

In closing, DuTeaux noted that data collected during disaster response research could potentially be used in an enforcement action. Data should be secured, and researchers should follow up with local response and recovery authorities on next steps and leave their contact information with the community and local public health authority.

_______________

1Free training courses through FEMA can be found at http://training.fema.gov/emiweb/is/icsresource/index.htm (accessed February 4, 2015).

RAPID RESEARCH: THE U.S. CRITICAL ILLNESS AND INJURY TRIALS GROUP

The U.S. Critical Illness and Injury Trials Group (USCIITG) entered disaster and preparedness research because of its interest in rapid identification of and intervention in life- threatening situations, said Charles Cairns, associate director of USCIITG. This application is similar to public health practice and disaster epidemiology, discussed in Chapter 7. For example, the group implemented a heart attack system that reduced mortality across the state of North Carolina by getting everyone treated within 90 minutes, independent of where they were at the time of their heart attack or their hospital system affiliation. USCIITG is a “network of networks,” including established research networks and professional organizations and more than 200 investigators across 68 intensive care units in U.S. hospitals. USCIITG has four main programs focused on identifying and enrolling patients within minutes of their intersection with the health care system: Prevention of Organ Failure; Critical Illness Outcomes Study; Early Intensive Care Unit (ICU) Rehabilitation; and Program for Emergency Preparedness (PREP).

The aim of PREP is to “significantly enhance the national capability to rapidly glean crucial information regarding the clinical course of acute illness and injury and guide clinical resource requirements during emergent events.” The goal is to not only collect these data, but to analyze them quickly and disseminate the results, ideally within 24 hours. Most of the datasets are geared to be done in a minute or two, Cairns said, and would be considered very minimal from the point of view of a specialty researcher; however, the way their approach is done is “better than perfect.” Cairns listed several of the key clinical outcomes and operational questions to be addressed by the data:

- What was the nature of the clinical insult and the resulting phenotype?

- As a clinical responder, what, if anything, did you have to do differently?

- Did clinical diagnostics, countermeasures, and therapies work as expected?

- What was the operational impact on the patient and care setting?

- Was there anything essential needed that you did not get?

- What is the best/worst case that could happen next time?

The first step to working with a rapid response clinical research network in a public health emergency is to define a key dataset. An all-hazard minimum dataset was defined as applicable to all phases of care (prehospital, emergency department, intensive care unit, discharge/followup, rehabilitation). The NIH Research Electronic Data Capture system was used so that the data could be collected using a smart device and would also be accessible to an analytic system. Specialized datasets were then developed, addressing specific hazards (infectious diseases, radiation injury, traumatic injury).

We see emergencies every day on a large scale. If we can leverage that experience, knowledge, and infrastructure, we should be able to conduct sound research, we should be able to analyze it quickly, and of course, through professional organizations and clinical care structures, disseminate the results rapidly.

—Charles Cairns

A clinical feasibility pilot study was then done to test the concepts and “field usability” of the core dataset in an everyday setting (burn injuries). The pilot also assessed the logistics of human subjects research in a public health emergency, especially IRB approval. Cairns reported that within 24 hours, 195 patients were enrolled across 12 sites, data were collected and reported to the coordination center, and analysis was disseminated, showing that it is possible to perform and share rapid assessments.

A key challenge highlighted by the pilot study was the IRB process, specifically, what was defined as research for the purposes of the IRB review, the time frames for review, and the variance in responses. These issues need to be addressed if we are to conduct clinically meaningful interventional research on time-sensitive, life-threatening illness and injury, Cairns said. Moving forward, he recommended reliance agreements in conjunction with an operational PHERRB (discussed at greater length earlier in this summary). Other considerations moving forward include the need for standardized data elements and reporting platforms for public health emergencies and coordinated international networks.

In conclusion, Cairns said that emergencies happen every day on a large scale. If we can leverage that experience, knowledge, and infrastructure, we should be able to conduct sound research, analyze it quickly, and disseminate the results rapidly through professional organizations and clinical care structures.

FEDERAL PERSPECTIVE ON LOGISTICS FOR RAPID DISASTER RESEARCH RESPONSE

The NIEHS Worker Education and Training Program is authorized under the Superfund Amendments and Reauthorization Act of 1986 to provide competitive training grants in hazardous waste removal and containment, and emergency responses involving toxic substances. The WETP Emergency Support Activation Plan is built on the protocols of the Worker Safety and Health Annex of the National Response Framework (NRF). Hughes of NIEHS noted that of the 15 Emergency Support Functions (ESFs) of the NRF, much of the NIEHS work over the years has been under ESF 8, Public Health and Medical Services (for which HHS is the lead) and ESF 10, Oil and Hazardous Materials Response (for which EPA is the lead). He suggested that disaster research could be built into the ESF structure, for example, public health research as part of ESF 8.

When a disaster happens, decisions about exposure and protection of first responders, workers, or communities often happen in a silo because the site-safety officer is disconnected to what might be happening in the field. Decisions are made based on the best data and information available at the moment. The earlier we can bring in better information, the better we can ensure that people do not engage in risky activities, Hughes said. The challenge is how to get information to people in the field when research information about hazards becomes available.

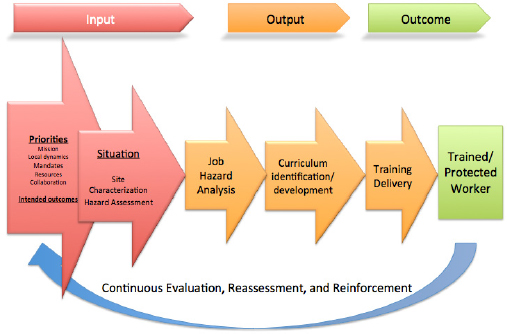

One approach to protecting workers is through site-specific training materials (see Figure 9-1). The NIEHS disaster response to the WTC collapses on 9/11 included, for example, on-site training for more than 7,000 response workers.

Deepwater Horizon oil spill response was another situation where instantaneous decisions about protection and risk had to be made, Hughes said. Just-in-time field training was provided for 150,000 people through short courses in English, Spanish, and Vietnamese. Training materials were developed by WETP together with BP, NIOSH, and the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA), and more than 35,000 training books were distributed.2

In response to Hurricane Sandy, WETP coordinated with OSHA and other agencies to provide site hazard assessments and develop site-

_______________

2Available at https://www.osha.gov/Publications/Oil_Spill_Booklet_05.11_v4.pdf (accessed December 18, 2014).

FIGURE 9-1 Site-specific training development.

SOURCE: Hughes presentation, June 13, 2014.

provided in-classroom, site-specific health and safety training for more than 3,000 cleanup workers, and hundreds of hours of technical assistance, training, and briefings were provided on-site.

In closing, Hughes concurred with the need to determine how research fits into the emergency response structure and the importance of connections to the ICS. Research should be ready to go, with pretrained responders, he said, and the acute response should help provide a foundation for further research (e.g., sample collection for later use, surveillance activities).

MAKING RESEARCH USEFUL TO THE RESPONSE

A critical gap in disaster research is during the disaster and immediately after impact, said Joseph Barbera, codirector of the Institute for Crisis, Disaster and Risk Management at George Washington University. Much of current research focuses on the predisaster and later postdisaster time frames, and there is a fair amount of disinformation around medical

problems that occur within the first hours after an event. The challenge is how to conduct good research in the immediate postimpact period when everything is chaotic, or at least recognize the limitations to close the gap as much as possible.

Collecting Perishable Data

Barbera emphasized the issue of perishable data. In a disaster, the scale, scope, and chaos can obscure the detail. Following an earthquake in the Philippines in 1990, for example, Baguio City in Luzon Province was completely isolated by landslides caused by the earthquakes. The only way in was by military aircraft. In addition to full-scale search and rescue, Barbera was trying to gather data from the three area hospitals for the Office of Foreign Disaster Assistance on which to base donation decisions. Barbera described the challenges of getting accurate information about how many patients the three local hospitals took care of in the first 24 hours after the earthquake. One hospital simply had no idea, as they cared for so many they were not even keeping track.

With perishable data there is also the issue of honest and unvarnished reporting versus processed and rationalized reporting, Barbera said. The raw story is the first time it is told, versus the polished version it becomes after many retellings. This is human behavior, often unintentional, and happens to everyone as our brains start to remember things differently, or the uncertainty starts to become less uncertain. This is why it is especially important to try to capture data rapidly in a sudden onset incident. Another phenomenon that is important to recognize when trying to capture data from a sudden onset incident is that the information reported can also evolve over time depending on why it is being provided. The story may lean one way early on when people or organizations are seeking assistance, and another way later when they are seeking to reduce potential liability (e.g., for performance during the disaster).

Barbera emphasized that part of data collection is also capturing the emergency context so that there can be accurate data interpretation. For example, Barbera shared how a man survived for 15 days buried in rubble following an earthquake in the Philippines in 1990 as a result of how the building collapsed and because rainwater was available. However, the situation was different after the earthquake in Haiti and searches were called off earlier as no further survivors were expected.

Sensitivities and Competencies

Sending researchers into disasters raises a variety of issues. The first concern highlighted by Barbera, and other speakers throughout this report, is the perception of research during a disaster. A situation is classified as a disaster because it exceeds resources, and research resources are often viewed as replacing response resources. Thus it is important to consider the relevancy of the research. Another issue is sensitivity, as the people impacted can feel that U.S. researchers come to their country and do research on their misfortunes so that the information can be used to help people in the researchers’ own country. There can also be similar sensitivities in local responses. Competency is another issue, and Barbera related it to the points made by DuTeaux about integrating research with the ICS. Researchers can be seen as interfering with or skewing the response, or potentially skewing later assessment of the response decisions and actions. Barbera told participants to think about how they would feel if firefighters had to respond to an incident in their research lab where all of their equipment and work is, and then to think of how firefighters might feel about researchers coming into an incident while they were working. Researchers might not be as physically destructive, he said, but could be every bit as functionally destructive.

One potential solution to these challenges, Barbera suggested, is to train responders to capture research data, although he acknowledged there are positives and negatives to that approach. Another approach, as noted by others, is for researchers to gain an operational level of proficiency with and participate in the ICS. One place for researchers to consider engaging is in the planning section of the ICS, in particular, the situation unit and the technical specialist unit. The planning section supports, promotes, and executes the development of the incident action plan for the next operational period. The situation unit is charged with capturing the data, particularly from the operation section, and putting that into a format that can inform decisions during the incident and action planning process. The data that might need to be collected to understand the situation at the action planning level are also data that could be very useful in research. Barbera added that collecting good data for the purposes of improvement of response might not need IRB approval and that data could be used later for research. Barbera noted that many of the ICS forms used for incident action planning contain data that could be used for research.

To study sudden onset events, researchers need to be able to deploy rapidly and have reliable transport to the incident. They need to know how

to check in with and integrate into the ICS even if they are “just doing research,” as this helps to build a trust relationship. Researchers also need to have an operational level of proficiency regarding safety and protective equipment, as well as other knowledge and skills relevant to operating in the disaster area (emphasizing DuTeaux’s earlier point around training in the ICS principles). It is also important that researchers understand the need to be self-sustaining (e.g., with regard to food, water, lodging/billeting). Barbera expressed concerns about “disaster tourism,” or people masquerading as researchers or clinicians. Researchers do not necessarily need to be at the scene, Barbera noted. Access to data could be facilitated through the emergency operation centers, for example, which directly support the incident management team. Researchers might also have services to offer the operations centers in terms of analyzing data in real time.

Overall, researchers should strive to be of use to the response, helping to collect data and rapidly disseminate raw aggregate information for use by appropriate responders. Be available to provide competent (i.e., situational) technical advice while conducting the research mission, and contribute to situation reports for incident action planning. Finally, Barbera said, consider this to be applied research. The disaster response becomes the research proof of concept for years of very intensive planning, peer review, and research. If we can understand these disaster contexts, we can develop useful strategies and tools and test the proofs of concept when they are needed (recognizing that there should be alternate plans that can be immediately implemented if the proof is not obtained).

A point reiterated throughout the discussion was the need to integrate research into the emergency response structure; Cairns reported in summarizing the session (see Box 9-1). There were discussions of public health integrating with state agencies and local responses, understanding where research fits into the ICS, and understanding that there are both operational and safety components that need to be addressed.

Another key issue was the need to identify the research priorities and key questions, and then develop data collection systems and train researchers, responders, and other partners to rapidly collect data to answer those questions. For example, Cairns said, do we want to understand the

BOX 9-1

Coordinating Logistics to Execute Rapid Research

in a Responsea

Challenges and Issues

- Integration with response structures and systems (ICS)

- Identify research questions and outcomes

- Capture immediate information (training, rapid data collection and systems)

Opportunities for Improvement

- Integrate research into elements of the Emergency Support Functions (ESFs)

- Centralized support for human subjects research (reliance agreements, PHERRB)

- Incorporate research into response training

- Develop a national research response framework

Critical Partnerships and Collaborations

- Response elements (local, state, federal)

- Trainers across multiple response dimension

- Federal research institutions (NIH, CDC, NSF, nonhealth)

______________

aThe challenges, opportunities, and partnerships listed were identified by one or more individual participants in this breakout panel discussion. This summary was prepared by the panel facilitator and presented in the subsequent plenary session. This list is not meant to reflect a consensus among workshop participants.

SOURCE: Plenary session summary of breakout panel discussion as reported by panel presenter Charles Cairns on behalf of facilitator Howard Zucker.

event; understand the systems of care and management; develop new interventions? The value of applied research is that it can help to answer immediate questions relevant to the response and provide decision makers with key information for allocating resources and meeting people’s needs, but it is also foundational data for later research and can inform policies and procedures going forward. Some participants highlighted the immediate post impact period as one of the information gaps in disasters and stressed

the need to collect “perishable” data rapidly and to collect contextual information associated with the data as well.

Cairns suggested that disaster research could be built into the ESF structure, particularly the public health–focused ESFs. A participant noted that the science required for response preparedness and recovery crosscuts all of the ESFs. The tendency is to focus on the health piece, but to be successful there needs to be a national research framework that includes everyone, local through federal, and public and private partners.

Part of the logistical network for disaster research would be centralized support for human subjects research, and similar to the IRB conversation, a few participants discussed the PHERRB and reliance agreements. The need for a national research response framework was also discussed, potentially integrating the elements of human subjects protection, minimum datasets, standardized terminology and processes, research training, the ICS, and public health emergency structures at the local, state, and national levels.

This page intentionally left blank.