ZOONOSIS EMERGENCE LINKED TO AGRICULTURAL INTENSIFICATION AND ENVIRONMENTAL CHANGE27

Bryony A. Jones, 28,29Delia Grace,29Richard Kock,30Silvia Alonso,28Jonathan Rushton,28Mohammed Y. Said,29Declan McKeever,30Florence Mutua,29Jarrah Young,29John McDermott,29and Dirk U. Pfeiffer28

Abstract

A systematic review was conducted by a multidisciplinary team to analyze qualitatively best available scientific evidence on the effect of agricultural intensification and environmental changes on the risk of zoonoses for which there are epidemiological interactions between wildlife and livestock. The study found several examples in which agricultural intensification and/or environmental change were associated with an increased risk of zoonotic disease emergence, driven by the impact of an expanding human population and changing human behavior on the environment. We conclude that the rate of future zoonotic disease emergence or reemergence will be closely linked to the evolution of the agriculture–environment nexus. However, available research inadequately addresses the complexity and interrelatedness of environmental, biological, economic, and social dimensions of zoonotic pathogen emergence, which significantly limits our ability to predict, prevent, and respond to zoonotic disease emergence.

_______________

27 Reprinted with permission from the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. Originally published as Jones et al. 2012. Zoonosis emergence linked to agricultural intensification and environmental change. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 110(21)8399–8484.

28 Veterinary Epidemiology, Economics and Public Health Group.

29 International Livestock Research Institute, Nairobi 00100, Kenya.

30 Department of Pathology and Infectious Diseases, Royal Veterinary College, University of London, Hertfordshire AL9 7TA, United Kingdom.

Since prehistoric time, major changes in human disease burden, spatial distribution, and pathogen types have arisen largely owing to human activity. The change from small hunter-gatherer to large agricultural communities was associated with the emergence of human contagious diseases, many of which are of animal origin. Travel and colonization facilitated the introduction of disease to naïve populations. In the last century, improved nutrition and hygiene and the use of vaccines and antimicrobials reduced the infectious disease burden. However, in recent decades, increasing global travel and trade, expanding human and livestock populations, and changing behavior have been linked to a rise in disease emergence risk and the potential for pandemics (Harper and Armelagos, 2010; McMichael, 2004; Morse, 1995).

An analysis of human pathogens revealed that 58% of species were zoonotic, and 13% were emerging, of which 73% were zoonotic (Woolhouse and Gowtage-Sequeria, 2005). A similar study found that 26% of human pathogens also infected both domestic and wild animals (Cleaveland et al., 2001). Emerging pathogens are more likely to be viruses than other pathogen types and more likely to have a broad host range (Cleaveland et al., 2001; Woolhouse and Gowtage-Sequeria, 2005). Many recently emerged zoonoses originated in wildlife, and the risk of emerging zoonotic disease events of wildlife origin is higher nearer to the equator (Jones et al., 2008). The human health burden and livelihood impact of zoonotic disease in developing countries are greater than in the developed world, but lack of diagnosis and underreporting mean that the contribution of zoonotic disease to total human disease burden is not sufficiently understood (Maudlin et al., 2009).

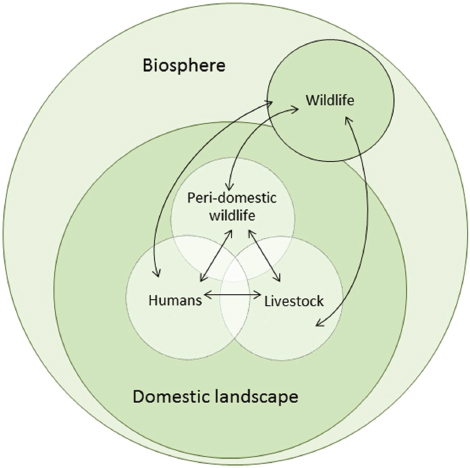

The interaction of humans or livestock with wildlife exposes them to sylvatic disease cycles and the risk of spillover of potential pathogens (Figure A11-1). Livestock may become intermediate or amplifier hosts in which pathogens can evolve and spill over into humans, or humans can be infected directly from wildlife or vectors (Childs et al., 2007). Human behavioral changes, driven by increasing population, economic and technological development, and the associated spatial expansion of agriculture, are creating novel as well as more intensive interactions between humans, livestock, and wildlife. These changes have been implicated as drivers of some recent emerging disease events (McMichael, 2004; Morse, 1995; Woolhouse and Gowtage-Sequeria, 2005) that had important impacts on human livelihoods and health. Sustainable agricultural food systems that minimize the risk of emerging disease will therefore be needed to meet the food requirements of the rising global population, while protecting human health and conserving biodiversity and the environment. These will require a better understanding of the drivers of disease emergence.

To inform the research policy of the United Kingdom’s Department of International Development, a systematic review was conducted to analyze qualitatively scientific knowledge in relation to the effect of agricultural intensification and environmental changes on risk of zoonoses at the wildlife–livestock–human interface.

FIGURE A11-1 Pathogen flow at the wildlife–livestock–human interface. Arrows indicate direct, indirect, or vector-borne candidate pathogen flow. In each host species there is a vast array of constantly evolving microorganisms, some of which are pathogenic in the host. These are a source of new organisms for other host species, some of which may be pathogenic in the new host or may evolve in the new host to become pathogenic. If the pathogen is also transmissible in the new host species then a new transmission cycle may be established. The rate and direction of candidate pathogen flow will depend on the nature and intensity of interaction between wildlife, livestock, and human compartments and the characteristics of the compartments (Table A11-1).

Results

In summary, the review found strong evidence that modern farming practices and intensified systems can be linked to disease emergence and amplification (Brown, 2004; Cutler et al., 2010; Daszak et al., 2000; Dorny et al., 2009; Epstein et al., 2006; Gould and Higgs, 2009; Gummow, 2010; McMichael, 2004; Newell

et al., 2010). However, the evidence is not sufficient to judge whether the net effect of intensified agricultural production is more or less propitious to disease emergence and amplification than if it was not used. Expansion of agriculture promotes encroachment into wildlife habitats, leading to ecosystem changes and bringing humans and livestock into closer proximity to wildlife and vectors, and the sylvatic cycles of potential zoonotic pathogens. This greater intensity of interaction creates opportunities for spillover of previously unknown pathogens into livestock or humans and establishment of new transmission cycles. Anthropogenic environmental changes arising from settlement and agriculture include habitat fragmentation, deforestation, and replacement of natural vegetation by crops. These modify wildlife population structure and migration and reduce biodiversity by creating environments that favor particular hosts, vectors, and/or pathogens.

Direct Pathogen Spillover from Wildlife to Humans

Examples of direct pathogen spillover from wildlife to humans are many. The emergence of HIV is believed to have arisen from hunting of nonhuman primates for food in central African forests, and outbreaks of Ebola hemorrhagic fever have been associated with hunting in Gabon and the Republic of Congo (Daszak et al., 2000; Gummow, 2010; Leroy et al., 2004). Transmission of rabies by vampire bats to cattle and humans was associated with forest activities in South America (Belotto et al., 2005), and Kyasanur Forest disease outbreaks followed encroachment of agriculture and cattle into Indian forests (Chomel et al., 2007; Varna, 2001). The early human cases of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) were associated with captive wildlife contact. It is likely that SARS corona virus-like virus of bats was transmitted, in the wild or in live animal markets, to various species of wild animal, such as masked palm civets (Parguma larvata), and spilled over into humans through contact with these intermediate hosts or their tissues, before establishing human–human transmission (Li et al., 2005).

Anthropogenic Environmental Change

Encroachment of human settlements and agriculture on natural ecosystems results in expansion of ecotones (transition zones between adjacent ecological systems), where species assemblages from different habitats mix. This provides new opportunities for pathogen spillover, genetic diversification, and adaptation. Associations between disease emergence and ecotones have been suggested for several diseases, including yellow fever, Lyme disease, hantavirus pulmonary syndrome, Nipah virus encephalitis, influenza, rabies, cholera, leptospirosis, malaria, and human African trypanosomiasis (Despommier et al., 2006). Most of these are zoonoses, and several involve both wildlife and livestock in their epidemiology.

Geographical expansion of Japanese encephalitis virus (JEV) in Southeast Asia has been associated with increasing irrigated rice production and pig farming due to an expanding human population (Pfeffer and Dobler, 2010; van den Hurk et al., 2009; Vora, 2008). The primary mosquito vector of JEV, Culex tritaeniorhynchus, breeds in irrigated areas, feeding primarily on herons and egrets but also on domestic and wild mammals. Although humans are dead-end hosts, pigs develop viremia and are amplifiers for human infection (Pfeffer and Dobler, 2010; van den Hurk et al., 2009). The combination of irrigated fields, which increase the density of vectors and water birds, and pig farming increases the risk of virus spillover into humans. Relocation of pigs away from households, in combination with human vaccination and vector control, has helped to decrease the incidence of human JEV in Japan, Taiwan, and Korea (van den Hurk et al., 2009).

A study of tsetse fly density and natural habitat fragmentation in eastern Zambia found that density was lowest in areas of greatest fragmentation, and intense human settlement and habitat clearance for agriculture has resulted in the disappearance of tsetse flies, which transmit human and animal trypanosomiasis (Ducheyne et al., 2009).

A study of the gut bacterium Escherichia coli in humans, livestock, and wildlife around Kibale National Park in Uganda found that isolates from humans and livestock living near forest fragments were genetically more similar to those from nonhuman primates in the forest fragments than to bacteria carried by nonhuman primates living in nearby undisturbed forest. The degree of similarity increased with the level of anthropogenic disturbance in the forest fragment (Goldberg et al., 2008). A second study in Bwindi Impenetrable National Park in Uganda found that the genetic similarity between E. coli isolated from humans and livestock and that of mountain gorillas increased with greater habitat overlap (Rwego et al., 2008). Higher interspecies transmission, which may be in either direction, is therefore likely to arise from greater ecological overlap.

The recent emergence of bat-associated viruses in Australia—Hendra virus, Australian bat lyssavirus, and Menangle virus—is associated with loss of bat habitat due to deforestation and agricultural expansion. Changes in the location, size, and structure of bat colonies, and foraging in periurban fruit trees have led to greater contact with livestock and humans, increasing the probability of pathogen spillover (Daszak et al., 2006; Field, 2009).

Loss of biodiversity can exacerbate the risk of pathogen spillover. In low diversity communities, vectors attain higher pathogen prevalences because they feed more frequently on primary reservoirs (Ostfeld, 2009; Vora, 2008). Conversely, vectors in high biodiversity communities feed on a wider range of hosts, some of which are poor pathogen reservoirs, often resulting in lower pathogen prevalence at ecological community level, as evidenced by the negative correlation between bird diversity and human West Nile virus incidence in the United States (Ostfeld, 2009). Forest fragmentation in North America has led to an increased risk of Lyme disease in humans as a result of reduced biodiversity and

the associated increase in the density of the white-footed mouse (Peromyscus leucopus), an efficient host for the causative agent, Borrelia burgdorferi, and its tick vector (Mathews, 2009; Pongsiri et al., 2009). Ticks occurring in forests with high vertebrate diversity have lower B. burgdorferi infection prevalence than ticks in low vertebrate diversity habitats, and there is a greater abundance of ticks in low diversity habitats (Ostfeld, 2009). The reemergence in Brazil of Chagas disease, caused by Trypanosoma cruzi, has been attributed to anthropogenic environmental change leading to low mammal diversity and abundance of the common opossum, Didelphis aurita (Vaz et al., 2007). T. cruzi sero-prevalence in small wild mammals in fragmented habitats was found to be higher than in continuous forest habitat owing to low small mammal diversity and increased marsupial abundance. Similar effects have been observed for leishmaniasis, Rocky Mountain spotted fever, and schistosomiasis (Vora, 2008).

Water management activities may result in increased density of breeding sites for mosquitoes. Rift Valley fever epidemics have occurred after the construction of dams and irrigation canals (Pepin et al., 2010). Liver fluke and its intermediate snail host have adapted to the irrigation systems of the Nile Delta in Egypt and in Peru, leading to increasing incidence of human fascioliasis (Mas-Coma et al., 2005). The effect of fertilizer use on disease dynamics varies depending on the pathogen, the host, the ecosystem, and the level of environmental nutrient enrichment (ENE), but parasites with complex life cycles, especially trematodes, increase in abundance under nutrient-rich conditions because their intermediate hosts—snails, worms, crustaceans—have increased population density and survival of infection. Increases in ENE in tropical and subtropical regions as agriculture develops may have an important impact because of the diversity of infectious pathogens in these areas (Johnson et al., 2010). The use of manure as a fertilizer may increase transmission of food-borne pathogens such as verotoxigenic E. coli and Salmonella (Newell et al., 2010).

Intensification of Livestock Farming

Intensification of livestock production, especially pigs and poultry, facilitates disease transmission by increasing population size and density (Cutler et al., 2010; Drew, 2011; Graham et al., 2008), although effective management and biosecurity measures will mitigate the between-herd spread of zoonotic diseases, such as brucellosis and tuberculosis (Perry et al., 2013). As an alternative to investing in improved husbandry or in situations of poor animal health service provision, antimicrobials are often used for growth promotion, disease prevention, or therapeutically, which in turn promotes the evolution of antimicrobial resistance in zoonotic pathogens (Gilchrist et al., 2007). Intensification also requires greater frequency of movement of people and vehicles on and off farms, which further increases the risk of pathogen transmission (Leibler et al., 2010).

Intensive livestock farming can promote disease transmission through environmental pathways (Graham et al., 2008). Ventilation systems expel material, including pathogens such as Campylobacter and avian influenza virus, into the environment, increasing risk of transmission to wild and domestic animals. Large quantities of waste are produced that contain a variety of pathogens capable of survival for several months if left untreated. Much of the waste is spread on land, where it can come into contact with wild animals and contaminate water. Similarly, use of animal waste in aquaculture leads to potential contact with wild birds (Graham et al., 2008).

Intensive farms use fewer workers per animal, thereby reducing the number of people exposed to zoonoses compared with extensive systems. However, several cross-sectional studies report higher sero-prevalence in farm workers of pandemic H1N1/09 influenza, hepatitis E, and highly pathogenic avian influenza H5 and H7 (Gilchrist et al., 2007; Graham et al., 2008) compared with the general community.

Intensive livestock systems generally have high density populations of low genetic diversity, which may favor increased transmission and adaptation (Drew, 2011). Epidemiological modeling experiments indicate that lower genetic diversity was associated with an increased probability of a major epidemic or no epidemic at all, whereas a more diverse population had a higher probability of a minor epidemic (Springbett et al., 2003).

Food-borne bacterial pathogens evolve in response to environmental changes, developing new virulence properties and occupying new niches, including antimicrobial resistance (Newell et al., 2010). Such evolution can be facilitated by intensified livestock systems. Increases in human salmonellosis have been due to the adaptation of Salmonella enteritidis phage type 4 to the poultry reproductive tract, and the emergence of vero cytotoxin-producing E. coli O157 to infect humans via contaminated beef and by environmental transmission (Newell et al., 2010).

Nipah Virus Emergence Linked to Livestock Intensification and Environmental Change

The first known outbreak of Nipah virus occurred in Malaysia during 1998–1999, causing respiratory disease in pigs and high case fatality in humans. Epidemiological outbreak investigation showed that pig and human cases had occurred in 1997 on a large intensive pig farm in northern Malaysia (Epstein et al., 2006), where Nipah virus-infected fruit bats were attracted to fruit trees planted around the farm. This provided the opportunity for virus spillover to susceptible pigs via consumption of fruit contaminated with bat saliva or urine. Respiratory spread of infection between pigs was facilitated by high pig and farm density and transport of pigs between farms to the main outbreak area in south Malaysia (Daszak et al., 2006; Field, 2009). Pigs then acted as amplifier hosts for human infection (Field, 2009). Almost all human cases had contact with pigs; there was no evidence of

direct spillover from bats to humans or of human-to-human transmission (Epstein et al., 2006). The outbreak was controlled by mass culling of pigs, and there have been no further outbreaks of Nipah virus in Malaysia (Epstein et al., 2006). Nipah virus was found to be closely related to Hendra virus, for which the reservoir hosts are Pteropus sp. fruit bats. A high sero-prevalence was found in several species of Malaysian bats, suggesting that they are reservoirs and that the virus is endemic (Chua et al., 2002; Epstein et al., 2006; Yob et al., 2001). Epstein et al. (2006) and Daszak et al. (2006) propose that Malaysian bats have historically been infected with Nipah virus and that there has probably been sporadic bat-to-pig and pig-to-human transmission. They hypothesize that the initial 1997 outbreak on the index pig farm died out quickly, causing only a few human cases, but the reintroduction of virus into a partially immune population in 1998 resulted in prolonged circulation on the farm, increasing the risk of spread to other farms and to humans. When infected pigs were sold from the affected farm to the south, where there was a high density of smaller intensive pig farms and a high human density, a large outbreak occurred in humans, stimulating an investigation and the discovery of Nipah virus as the causative agent (Daszak et al., 2006; Epstein et al., 2006). They conclude that the emergence of Nipah virus was primarily driven by intensification of the pig industry combined with fruit production in an area already populated by Nipah virus-infected fruit bats.

In contrast, seasonal clusters of human Nipah encephalitis cases occurred in Bangladesh and India between 2001 and 2005, with no apparent intermediate host (Field, 2009). Serological surveys found Nipah virus antibodies in Pteropus giganteus fruit bats but no evidence of infection in pigs or other animals (Daszak et al., 2006; Hsu et al., 2004). It is believed that humans in these outbreaks acquired infection initially from bats via contaminated date palm sap and that the outbreaks spread through human-to-human transmission (Daszak et al., 2006; Epstein et al., 2006). There is serological evidence that henipaviruses occur throughout the range of pteropid bat species, which occur from Madagascar to South and Southeast Asia, Australasia, and Pacific Islands (Epstein et al., 2006). Surveys in bats in India, Indonesia, Cambodia, Thailand, and Madagascar have found Nipah virus RNA or virus-neutralizing antibodies (Epstein et al., 2008; Iehle et al., 2007; Reynes et al., 2005; Sendow et al., 2006; Wacharapluesadee et al., 2010). Nipah and Hendra virus-neutralizing antibodies and henipavirus RNA were also found in Eidolon helvum fruit bats sampled in Ghana in West Africa, demonstrating that henipaviruses are not restricted to the range of pteropid bats (Drexler et al., 2009; Hayman et al., 2008).

Influenza A Virus Emergence Linked to Poultry Farming Practices

Influenza A viruses are segmented RNA viruses that evolve constantly by reassortment and mutation to create new strains of varying pathogenicity and host range (Landolt and Olsen, 2007; Pekosz and Glass, 2008). They are found

in birds, humans, pigs, horses, cats, dogs, and other animals (Landolt and Olsen, 2007; Riedel, 2006). Aquatic birds are considered to be the natural reservoir hosts (Irvine and Brown, 2009; Landolt and Olsen, 2007) and seem to host a variety of ephemeral variants rather than a single discrete strain (Dugan et al., 2008). Avian influenza is usually subclinical or of low pathogenicity in wild birds (Artois et al., 2009), but some strains may be highly pathogenic when introduced to domestic poultry (Landolt and Olsen, 2007). Swine influenza occurs in several subtypes in pigs worldwide, and infection may be transmitted between pigs, birds, and humans (Irvine and Brown, 2009; Landolt and Olsen, 2007).

Both extensive and intensive farming practices can influence the likelihood of influenza virus spillover from wild birds to domestic birds and pigs and the subsequent evolution and amplification in domestic animals and transmission to humans. Rice paddies combined with free-grazing duck farming in wetland areas bring wild water birds into close proximity with domestic water birds (Artois et al., 2009; Gilbert et al., 2007). The latter are susceptible to infection but less likely to develop disease than chickens and are infectious to other domestic poultry by direct contact or environmental contamination (Sims et al., 2005). Other low biosecurity rearing systems, such as scavenging poultry, household poultry, and small-scale commercial poultry, also allow direct or indirect contact between wild and domestic birds (Artois et al., 2009; Sims et al., 2005).

Although high biodiversity of the wild bird population can increase the risk of pathogen spillover, low genetic diversity in the domestic population encourages rapid dissemination of infection if the latter are susceptible (Drew, 2011; Keesing et al., 2010). The expansion of intensive livestock production in the last few decades, particularly for short generation interval species such as poultry and pigs, creates large high density populations in which there is an increased probability of adaptation of an introduced influenza virus and amplification for transmission between farms, to humans, and to wild animals (Gilbert et al., 2007; Graham et al., 2008; Kapan et al., 2006). The increased trade in poultry and poultry products can rapidly spread infection to new farms, areas, or countries, whether by small-scale informal or formal trade or large-scale commercial trade. Live bird markets in particular play an important role in disseminating infection and provide opportunities for cross-species transmission between domestic and wild birds (Fevre et al., 2006; Sims et al., 2005).

The human disease impact of recently emerged human pathogenic influenza viruses has been lower than was observed during the pandemics of the last century, but the potential remains for the evolution of a variant that is both highly transmissible to humans and of high pathogenicity (Landolt and Olsen, 2007). Farming systems that allow contact between wild and domestic birds and pigs and have large high density populations that facilitate transmission, adaption, and amplification are increasing the risk that such a pandemic variant will emerge.

Discussion

The results from this work will inform the research policy of the United Kingdom Department of International Development. Given the broad nature of the study question and the potential for significant biases, we decided that a systematic review approach was required, so that the scientific knowledge base could be examined in a structured and transparent manner. A key objective was to obtain as complete a literature database as possible. Most of the publications that were included did not present data and results suitable for quantitative analysis, such as metaanalysis, and therefore the interpretation needed to be based on qualitative methods.

Some of the limitations of our approach included the following: few papers described primary research; different review papers tended to be based on the same small number of primary research papers; the diversity of studies prevented metaanalysis; and non-English language papers were excluded from the initial database search.

This systematic review found several examples of zoonotic disease emergence at the wildlife–livestock–human interface that were associated with varying combinations of agricultural intensification and environmental change, such as habitat fragmentation and ecotones, reduced biodiversity, agricultural changes, and increasing human density in ecosystems. Expansion of livestock production, especially in proximity to wildlife habitats, has facilitated pathogen spillover from wildlife to livestock and vice versa and increased the likelihood that livestock become amplifying hosts in which pathogens can evolve and become transmissible to humans. Some wildlife species have adapted to and thrived in the ecological landscape created by human settlement and agriculture and have become reservoirs for disease in livestock and humans. Table A11-1 provides a conceptual framework of the characteristics of the types of wildlife–livestock–human interface where zoonotic disease has emerged or reemerged.

Human population growth and associated changes and increases in demand for food and other commodities are drivers of environmental change, such as urbanization, agricultural expansion and intensification, and habitat alteration. These play an important role in the emergence and reemergence of infectious diseases by affecting ecological systems at landscape and community levels, as well as host and pathogen population dynamics. Climate variability interacts with these environmental changes to contribute to disease emergence (Wilcox and Colwell, 2005). Changes in the ecosystem can lead to increased pathogen transmission between hosts or greater contact with new host populations or host species. This occurs against a background of pathogen evolution and selection pressure, leading to emergence of pathogen strains that are adapted to the new conditions (Daszak et al., 2001). The intensity of the interface between wildlife, humans, and domestic animal species has never been static, and all biological systems have an inherent capacity for both resilience and adaptation (Redman and

| Type of wildlife–livestock–human interface | Level of biodiversity | Characteristics of livestock population | Connectedness between populations | Examples of zoonotic disease with altered dynamics |

| “Pristine” ecosystem with human incursion to harvest wildlife and other resources | High | No livestock | Very low, small populations and limited contact | Ebola, HIV, SARS, Nipah virus in Bangladesh and India |

| Ecotones and fragmentation of natural ecosystems: farming edges, human incursion to harvest natural resources | High but decreasing | Few livestock, multiple species, mostly extensive systems | Increasing contact between people, livestock, and wild animals | Kyasanur Forest disease, Bat rabies, E. coli interspecies transmission in Uganda, Nipah virus in Malaysia |

| Evolving landscape: rapid intensification of agriculture and livestock, alongside extensive and backyard farming | Low, but increasing peridomestic wildlife | Many livestock, both intensive and genetically homogenous, as well as extensive and genetically diverse | High contacts between intensive and extensive livestock, people, and peridomestic wildlife. Less with endangered wildlife. | Avian influenza, Japanese encephalitis virus in Asia |

| Managed landscape: islands of intensive farming, highly regulated. Farm land converted to recreational and conservancy | Low, but increased number of certain peridomestic wildlife species | Many livestock, mainly intensive, genetically homogeneous, biosecure | Fewer contacts between livestock, and people; increasing contacts with wildlife. | Bat-associated viruses in Australia, West Nile virus in United States, Lyme disease in United States |

Kinzig, 2003), but the current pace of anthropogenic change could be too fast to allow system adaptation and overwhelm resilience.

In pristine or natural ecosystems, coevolution of host and pathogens tends to favor low pathogenicity microorganisms. In intensive systems, genetic selection and management of livestock creates frequent contact opportunities, high animal numbers, and low genetic diversity, providing opportunities for “wild” microorganisms to invade and amplify or for existing pathogens to evolve to new and more pathogenic forms. Human influence on the ecosystem through farming practices, extensive transportation networks, sale of live animals, and juxtaposition of agriculture or recreation with wildlife all contribute to emergence and shifting virulence of pathogens.

Key features of the systems within which these processes occur are their complexity, connectedness, feedback loops, and emerging properties. These cannot be captured by the single- or multidisciplinary approaches that the majority of published research is still based on, and simple globally generalizable explanations for zoonoses emergence are not possible. Instead the geographical diversity and complexity of systems requires local interdisciplinary studies to be conducted to generate locally relevant solutions. A priority for research therefore should be a holistic perspective on pathogen dynamics at the wildlife–livestock–human interface, based on an interdisciplinary approach to the examination of biological, ecological, economic, and social drivers of pathogen emergence. Investigations are required on the frequency and risks of pathogen flow between species, the mechanisms of amplification and persistence, the influence of different livestock production systems, and the socioeconomic context, to identify possible interventions to reduce pathogen emergence, as well as more effective strategies for responding to such events.

In conclusion, we find that available research clearly indicates the significance of the zoonotic disease threat associated with the wildlife–livestock interface. However, it inadequately addresses the complexity, context specificity, and interrelatedness of the environmental, biological, and social dimensions of zoonotic pathogen emergence and has therefore failed to generate scientific evidence to underpin effective management of zoonotic disease risk at the wildlife–livestock interface.

Methods

A qualitative systematic review was carried out during late 2010 to early 2011 by a multidisciplinary team with expertise in epidemiology, socioeconomics, and ecology. A systematic review is an analytical research study design that follows a structured approach toward selecting, analyzing, and interpreting available empirical evidence in an integrated way to answer a specific research question while explicitly taking potential bias into account (Tricco et al., 2011). The full protocol for conducting the review is provided as supplementary material

(SI Methods, Fig. S1, and Tables S1–S3) and is summarized here. The overall objective of the study was to analyze scientific knowledge in relation to zoonotic disease transmission by direct or indirect livestock–wildlife interaction, with emphasis on risk factors, drivers, and trajectories of transmission. This article focuses on those study findings that provide evidence of the effect of agricultural intensification and environmental change on zoonosis at the wildlife–livestock–human interface.

The overall objective was broken down into seven themes, for which literature database search terms and algorithms were defined. More than 280 unique algorithms were used and more than 100 keywords. Several databases were explored to assess the number and quality of papers identified, and PubMed (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed) and CAB Direct (www.cabdirect.org) were selected. The initial search criteria were English language papers published from 2006 to 2010 describing primary research and reviews. A total of 1,022 relevant published papers were identified by searching their titles and abstracts for specified key words. The abstracts were independently reviewed by at least two reviewers to identify those that contained relevant information, and 261 papers were selected to be assessed for eligibility using forms for data extraction and assessment of study quality (SI Methods). One hundred forty-five papers were eligible for inclusion. A further 133 papers were identified by screening the reference lists of the eligible papers and inclusion of relevant papers already known to the team. This resulted in a total of 278 eligible papers, 57 of which were relevant to the topic of this article. Because of the wide variation in type of study, geographical location, pathogens, and host species it was not possible to conduct quantitative metaanalysis, so information was extracted, summarized, and organized by emerging themes; these are the headings used in Results in this article.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the Department for International Development, United Kingdom.

References

Artois, M., D. Bicout, D. Doctrinal, R. Fouchier, D. Gavier-Widen, A. Globig, W. Hagemeijer, T. Mundkur, V. Munster, and B. Olsen. 2009. Outbreaks of highly pathogenic avian influenza in Europe: the risks associated with wild birds. Revue Scientifique et Technique 28(1):69-92.

Belotto, A., L. F. Leanes, M. C. Schneider, H. Tamayo, and E. Correa. 2005. Overview of rabies in the Americas. Virus Research 111(1):5-12.

Brown, C. 2004. Emerging zoonoses and pathogens of public health significance—An overview. Revue Scientifique et Technique 23(2):435-442.

Childs, J. E., J. A. Richt, and J. S. Mackenzie. 2007. Introduction: Conceptualizing and partitioning the emergence process of zoonotic viruses from wildlife to humans. Current Topics in Microbiology and Immunology 315:1-31.

Chomel, B. B., A. Belotto, and F. X. Meslin. 2007. Wildlife, exotic pets, and emerging zoonoses. Emerging Infectious Diseases 13(1):6-11.

Chua, K. B., C. L. Koh, P. S. Hooi, K. F. Wee, J. H. Khong, B. H. Chua, Y. P. Chan, M. E. Lim, and S. K. Lam. 2002. Isolation of Nipah virus from Malaysian Island flying-foxes. Microbes Infect 4(2):145-151.

Cleaveland, S., M. K. Laurenson, and L. H. Taylor. 2001. Diseases of humans and their domestic mammals: pathogen characteristics, host range and the risk of emergence. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London B Biological Sciences 356(1411):991-999.

Cutler, S. J., A. R. Fooks, and W. H. van der Poel. 2010. Public health threat of new, reemerging, and neglected zoonoses in the industrialized world. Emerging Infectious Diseases 16(1):1-7.

Daszak, P., A. A. Cunningham, and A. D. Hyatt. 2000. Emerging infectious diseases of wildlife—Threats to biodiversity and human health. Science 287(5452):443-449.

———. 2001. Anthropogenic environmental change and the emergence of infectious diseases in wildlife. Acta Tropica 78(2):103-116.

Daszak, P., R. Plowright, J. Epstein, J. Pulliam, S. Abdul Rahman, H. Field, C. Smith, K. Olival, S. Luby, and K. Halpin. 2006. The emergence of Nipah and Hendra virus: pathogen dynamics across a wildlife–livestock–human continuum. Disease ecology: community structure and pathogen dynamics:186-201.

Despommier, D., B. R. Ellis, and B. A. Wilcox. 2006. The role of ecotones in emerging infectious diseases. EcoHealth 3(4):281-289.

Dorny, P., N. Praet, N. Deckers, and S. Gabriel. 2009. Emerging food-borne parasites. Veterinary Parasitology 163(3):196-206.

Drew, T. W. 2011. The emergence and evolution of swine viral diseases: to what extent have husbandry systems and global trade contributed to their distribution and diversity? Revue Scientifique et Technique 30(1):95-106.

Drexler, J. F., V. M. Corman, F. Gloza-Rausch, A. Seebens, A. Annan, A. Ipsen, T. Kruppa, M. A. Muller, E. K. Kalko, Y. Adu-Sarkodie, S. Oppong, and C. Drosten. 2009. Henipavirus RNA in African bats. PloS One 4(7):e6367.

Ducheyne, E., C. Mweempwa, C. De Pus, H. Vernieuwe, R. De Deken, G. Hendrickx, and P. Van den Bossche. 2009. The impact of habitat fragmentation on tsetse abundance on the plateau of eastern Zambia. Preventive Veterinary Medicine 91(1):11-18.

Dugan, V. G., R. Chen, D. J. Spiro, N. Sengamalay, J. Zaborsky, E. Ghedin, J. Nolting, D. E. Swayne, J. A. Runstadler, G. M. Happ, D. A. Senne, R. Wang, R. D. Slemons, E. C. Holmes, and J. K. Taubenberger. 2008. The evolutionary genetics and emergence of avian influenza viruses in wild birds. PLoS Pathogens 4(5):e1000076.

Epstein, J. H., H. E. Field, S. Luby, J. R. Pulliam, and P. Daszak. 2006. Nipah virus: impact, origins, and causes of emergence. Current Infectious Disease Reports 8(1):59-65.

Epstein, J. H., V. Prakash, C. S. Smith, P. Daszak, A. B. McLaughlin, G. Meehan, H. E. Field, and A. A. Cunningham. 2008. Henipavirus infection in fruit bats (Pteropus giganteus), India. Emerging Infectious Diseases 14(8):1309-1311.

Fevre, E. M., B. M. Bronsvoort, K. A. Hamilton, and S. Cleaveland. 2006. Animal movements and the spread of infectious diseases. Trends in Microbiology 14(3):125-131.

Field, H. E. 2009. Bats and emerging zoonoses: henipaviruses and SARS. Zoonoses and Public Health 56(6-7):278-284.

Gilbert, M., X. Xiao, P. Chaitaweesub, W. Kalpravidh, S. Premashthira, S. Boles, and J. Slingenbergh. 2007. Avian influenza, domestic ducks and rice agriculture in Thailand. Agriculture Ecosystems & Environment 119:409-415.

Gilchrist, M. J., C. Greko, D. B. Wallinga, G. W. Beran, D. G. Riley, and P. S. Thorne. 2007. The potential role of concentrated animal feeding operations in infectious disease epidemics and antibiotic resistance. Environmental Health Perspectives 115(2):313-316.

Goldberg, T. L., T. R. Gillespie, I. B. Rwego, E. L. Estoff, and C. A. Chapman. 2008. Forest fragmentation as cause of bacterial transmission among nonhuman primates, humans, and livestock, Uganda. Emerging Infectious Diseases 14(9):1375-1382.

Gould, E. A., and S. Higgs. 2009. Impact of climate change and other factors on emerging arbovirus diseases. Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 103(2):109-121.

Graham, J. P., J. H. Leibler, L. B. Price, J. M. Otte, D. U. Pfeiffer, T. Tiensin, and E. K. Silbergeld. 2008. The animal–human interface and infectious disease in industrial food animal production: rethinking biosecurity and biocontainment. Public Health Reports 123(3):282-299.

Gummow, B. 2010. Challenges posed by new and re-emerging infectious diseases in livestock production, wildlife and humans. Livestock Science 130(1):41-46.

Harper, K., and G. Armelagos. 2010. The changing disease-scape in the third epidemiological transition. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 7(2):675-697.

Hayman, D. T., R. Suu-Ire, A. C. Breed, J. A. McEachern, L. Wang, J. L. Wood, and A. A. Cunningham. 2008. Evidence of henipavirus infection in West African fruit bats. PloS One 3(7):e2739.

Hsu, V. P., M. J. Hossain, U. D. Parashar, M. M. Ali, T. G. Ksiazek, I. Kuzmin, M. Niezgoda, C. Rupprecht, J. Bresee, and R. F. Breiman. 2004. Nipah virus encephalitis reemergence, Bangladesh. Emerging Infectious Diseases 10(12):2082-2087.

Iehle, C., G. Razafitrimo, J. Razainirina, N. Andriaholinirina, S. M. Goodman, C. Faure, M. C. Georges-Courbot, D. Rousset, and J. M. Reynes. 2007. Henipavirus and Tioman virus antibodies in pteropodid bats, Madagascar. Emerging Infectious Diseases 13(1):159-161.

Irvine, R. M., and I. H. Brown. 2009. Novel H1N1 influenza in people: global spread from an animal source? Veterinary Record 164(19):577-578.

Johnson, P. T., A. R. Townsend, C. C. Cleveland, P. M. Glibert, R. W. Howarth, V. J. McKenzie, E. Rejmankova, and M. H. Ward. 2010. Linking environmental nutrient enrichment and disease emergence in humans and wildlife. Ecological Applications 20(1):16-29.

Jones, K. E., N. G. Patel, M. A. Levy, A. Storeygard, D. Balk, J. L. Gittleman, and P. Daszak. 2008. Global trends in emerging infectious diseases. Nature 451(7181):990-993.

Kapan, D. D., S. N. Bennett, B. N. Ellis, J. Fox, N. D. Lewis, J. H. Spencer, S. Saksena, and B. A. Wilcox. 2006. Avian influenza (H5N1) and the evolutionary and social ecology of infectious disease emergence. EcoHealth 3(3):187-194.

Keesing, F., L. K. Belden, P. Daszak, A. Dobson, C. D. Harvell, R. D. Holt, P. Hudson, A. Jolles, K. E. Jones, C. E. Mitchell, S. S. Myers, T. Bogich, and R. S. Ostfeld. 2010. Impacts of biodiversity on the emergence and transmission of infectious diseases. Nature 468(7324):647-652.

Landolt, G. A., and C. W. Olsen. 2007. Up to new tricks—A review of cross-species transmission of influenza A viruses. Animal Health Research Reviews 8(1):1-21.

Leibler, J. H., M. Carone, and E. K. Silbergeld. 2010. Contribution of company affiliation and social contacts to risk estimates of between-farm transmission of avian influenza. PloS One 5(3):e9888.

Leroy, E. M., P. Rouquet, P. Formenty, S. Souquiere, A. Kilbourne, J. M. Froment, M. Bermejo, S. Smit, W. Karesh, R. Swanepoel, S. R. Zaki, and P. E. Rollin. 2004. Multiple Ebola virus transmission events and rapid decline of central African wildlife. Science 303(5656):387-390.

Li, W., Z. Shi, M. Yu, W. Ren, C. Smith, J. H. Epstein, H. Wang, G. Crameri, Z. Hu, H. Zhang, J. Zhang, J. McEachern, H. Field, P. Daszak, B. T. Eaton, S. Zhang, and L. F. Wang. 2005. Bats are natural reservoirs of SARS-like coronaviruses. Science 310(5748):676-679.

Mas-Coma, S., M. D. Bargues, and M. A. Valero. 2005. Fascioliasis and other plant-borne trematode zoonoses. International Journal for Parasitology 35(11-12):1255-1278.

Mathews, F. 2009. Zoonoses in wildlife integrating ecology into management. Advances in Parasitology 68:185-209.

Maudlin, I., M. C. Eisler, and S. C. Welburn. 2009. Neglected and endemic zoonoses. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London B Biological Sciences 364(1530):2777-2787.

McMichael, A. J. 2004. Environmental and social influences on emerging infectious diseases: past, present and future. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London B Biological Sciences 359(1447):1049-1058.

Morse, S. S. 1995. Factors in the emergence of infectious diseases. Emerging Infectious Diseases 1(1):7-15.

Newell, D. G., M. Koopmans, L. Verhoef, E. Duizer, A. Aidara-Kane, H. Sprong, M. Opsteegh, M. Langelaar, J. Threfall, F. Scheutz, J. van der Giessen, and H. Kruse. 2010. Food-borne diseases—The challenges of 20 years ago still persist while new ones continue to emerge. International Journal of Food Microbiology 139 Suppl 1:S3-15.

Ostfeld, R. S. 2009. Biodiversity loss and the rise of zoonotic pathogens. Clinical Microbiology and Infection 15 Suppl 1:40-43.

Pekosz, A., and G. E. Glass. 2008. Emerging viral diseases. Maryland Medicine 9(1):11, 13-16.

Pepin, M., M. Bouloy, B. H. Bird, A. Kemp, and J. Paweska. 2010. Rift Valley fever virus (Bunyaviridae: Phlebovirus): an update on pathogenesis, molecular epidemiology, vectors, diagnostics and prevention. Veterinary Research 41(6):61.

Perry, B. D., D. Grace, and K. Sones. 2013. Current drivers and future directions of global livestock disease dynamics. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 110(52):20871-20877.

Pfeffer, M., and G. Dobler. 2010. Emergence of zoonotic arboviruses by animal trade and migration. Parasit Vectors 3(1):35.

Pongsiri, M. J., J. Roman, V. O. Ezenwa, T. L. Goldberg, H. S. Koren, S. C. Newbold, R. S. Ostfeld, S. K. Pattanayak, and D. J. Salkeld. 2009. Biodiversity loss affects global disease ecology. Bioscience 59(11):945-954.

Redman, C. L., and A. P. Kinzig. 2003. Resilience of past landscapes: resilience theory, society, and the longue durée. Conservation Ecology 7(1):14.

Reynes, J. M., D. Counor, S. Ong, C. Faure, V. Seng, S. Molia, J. Walston, M. C. Georges-Courbot, V. Deubel, and J. L. Sarthou. 2005. Nipah virus in Lyle’s flying foxes, Cambodia. Emerging Infectious Diseases 11(7):1042-1047.

Riedel, S. 2006. Crossing the species barrier: the threat of an avian influenza pandemic. Proceedings (Baylor University Medical Center) 19(1):16-20.

Rwego, I. B., G. Isabirye-Basuta, T. R. Gillespie, and T. L. Goldberg. 2008. Gastrointestinal bacterial transmission among humans, mountain gorillas, and livestock in Bwindi Impenetrable National Park, Uganda. Conservation Biology 22(6):1600-1607.

Sendow, I., H. E. Field, J. Curran, Darminto, C. Morrissy, G. Meehan, T. Buick, and P. Daniels. 2006. Henipavirus in Pteropus vampyrus bats, Indonesia. Emerging Infectious Diseases 12(4):711-712.

Sims, L. D., J. Domenech, C. Benigno, S. Kahn, A. Kamata, J. Lubroth, V. Martin, and P. Roeder. 2005. Origin and evolution of highly pathogenic H5N1 avian influenza in Asia. Veterinary Record 157(6):159-164.

Springbett, A. J., K. MacKenzie, J. A. Woolliams, and S. C. Bishop. 2003. The contribution of genetic diversity to the spread of infectious diseases in livestock populations. Genetics 165(3): 1465-1474.

Tricco, A. C., J. Tetzlaff, and D. Moher. 2011. The art and science of knowledge synthesis. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 64(1):11-20.

van den Hurk, A. F., S. A. Ritchie, and J. S. Mackenzie. 2009. Ecology and geographical expansion of Japanese encephalitis virus. Annual Review of Entomology 54:17-35.

Varna, M. 2001. Kyasanur Forest disease. In The Encyclopedia of Arthropod-Transmitted Infections, edited by M. Service. New York: CABI. Pp. 254-260.

Vaz, V. C., P. S. D’Andrea, and A. M. Jansen. 2007. Effects of habitat fragmentation on wild mammal infection by Trypanosoma cruzi. Parasitology 134(Pt 12):1785-1793.

Vora, N. 2008. Impact of anthropogenic environmental alterations on vector-borne diseases. Medscape Journal of Medicine 10(10):238.

Wacharapluesadee, S., K. Boongird, S. Wanghongsa, N. Ratanasetyuth, P. Supavonwong, D. Saengsen, G. N. Gongal, and T. Hemachudha. 2010. A longitudinal study of the prevalence of Nipah virus in Pteropus lylei bats in Thailand: evidence for seasonal preference in disease transmission. Vector Borne and Zoonotic Diseases 10(2):183-190.