The United States spends more on health care than any other nation, yet there are many questions about the value that the nation receives for all of that spending and whether that spending is equitable. A 2013 report from the National Research Council (NRC) and the Institute of Medicine (IOM) found a pervasive pattern of health disadvantages in diverse categories of illness and injury that exists across age groups, sexes, racial and ethnic groups, and social classes (NRC and IOM, 2013). The same report also pointed out that significant health disparities exist between different income groups and geographic locations in the United States and that among the important contributors to these disparities are various social determinants, such as education and income, and also place-based characteristics of the physical and social environment in which people live and the macrostructural policies that shape them.

A recently published discussion paper (Zimmerman and Woolf, 2014) noted that of all the various social determinants that play a role in health disparities by geography or demographic characteristics, the literature has consistently identified education as a major factor. Indeed, the authors report that research based on decades of experience in the developing world has identified educational status, especially the status of the mother,

_____________________________

1 The planning committee’s role was limited to planning the workshop, and the workshop summary has been prepared by the workshop rapporteurs as a factual summary of what occurred at the workshop. Statements, recommendations, and opinions expressed are those of individual presenters and participants, and are not necessarily endorsed or verified by the Institute of Medicine, and they should not be construed as reflecting any group consensus.

as a major predictor of health outcomes and that the literature indicates that the gradient in health outcomes by educational attainment has steepened over the past four decades across the United States (Goldman and Smith, 2011). Other scholarship has examined the impacts of health on the ability of students to learn and the manner in which health contributes to the achievement gap between urban youth of color and white youths (Basch, 2011). Since the 1990s, while the average life expectancy in the United States has been steadily increasing, life expectancy has actually decreased for people without a high school education, especially white women (Olshansky et al., 2012).

To understand the complex relationship between education and health and how this understanding could inform our nation’s investments and policies, the IOM’s Roundtable on Population Health Improvement held a public workshop in Washington, DC, on June 5, 2014. This workshop, which featured presentations and extensive discussion periods, also explored how the health and education sectors can work together more effectively to achieve improvements in both health status and educational achievement. The workshop focused on three objectives:

- learning from education leaders about ways in which the health sector could support their efforts at the level of students, families, and schools through actions such as addressing health care needs, advocating for better health care for children, and promoting better connections between schools and the health care delivery system;

- learning from education leaders about which education policy efforts could benefit most from health sector partners’ contributions and what education or other policy and investment changes could contribute to benefits for both health and education; and

- highlighting state and local examples of successful collaboration between the health and education sectors.

THE ROUNDTABLE ON POPULATION HEALTH IMPROVEMENT

The Roundtable on Population Health Improvement provides a trusted venue for leaders from the public and private sectors to meet and discuss leverage points and opportunities for achieving population health that arise from changes in the social and political environment. The Roundtable’s vision is of a strong, healthful, and productive society that cultivates human capital and equal opportunity. The Roundtable recognizes that such outcomes as life expectancy, quality of life, and health are shaped by a variety of interdependent social, economic, environmental, genetic, behavioral, and health care factors and thus that achieving its vision will require robust national and community-based policies and dependable resources.

The goals of the Roundtable are to catalyze urgently needed action toward a stronger, more healthful, and more productive society and to facilitate sustainable collaborative action by a community of science-informed leaders in public health care, business, education, early childhood development, housing, agriculture, transportation, economic development, and nonprofit and faith-based organizations. To accomplish these lofty goals, the Roundtable has identified six areas of activity on which it is working:

- identifying and deploying key population health metrics;

- shedding light on and reflecting on the allocation of adequate resources to achieve improved population health;

- identifying, assessing, and reflecting on research and its implementation;

- discussing and helping stakeholders who work to develop and implement high-impact public and private population health policies;

- fostering and building relationships that will catalyze action to improve population health; and

- developing and deploying communication to educate about and motivate action directed at improving population health.

WORKSHOP SCOPE AND ORGANIZATION OF THE SUMMARY

In his introductory remarks, Roundtable co-chair and planning committee co-chair David Kindig, professor emeritus of population health sciences and emeritus vice chancellor at the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health, said that the evidence shows that education and health are linked in multiple and complex ways and that the workshop would highlight some of that evidence. In her opening comments, roundtable member and planning committee co-chair Gillian Barclay, vice president of the Aetna Foundation, pointed out that health care accounts for just a small portion of the factors that influence health. “Factors that reside in our socioeconomic and built environments, such as educational attainment, access to parks, and safe neighborhoods, have a great deal more to do with whether we are able to live long and healthy lives,” Barclay said, noting the increased recognition of the fact that it takes partnerships and collaborations across sectors to alter the non-health factors that shape health.

This workshop, the sixth in a series organized by the Roundtable, included an overview of a National Institutes of Health (NIH)-sponsored meeting on the evidence for education improving health that had been held a day earlier along with two keynote presentations and three panel discussions. This publication summarizes the discussions that occurred

during the workshop, highlighting the key lessons presented as well as opportunities for addressing the disparities in education that negatively impact health. Chapter 2 discusses the evidence for why educational attainment is crucial for improving population health. Chapter 3 considers how the health sector can support the education sector, and Chapter 4 discusses the connection between rising health care expenditures and diminishing funds for education and suggests some approaches for restructuring the nation’s investments in both health and education. Chapter 5 describes the potential for the health sector to contribute to the implementation of best evidence about what supports educational achievement, and Chapter 6 discusses state- and local-level collaborations between the health and education sectors. Chapter 7 recapitulates the wide-ranging end-of-workshop discussion and describes reflections on the day’s proceedings that were offered by various workshop participants.

REPORT ON THE JUNE 4 NIH MEETING ON THE EVIDENCE FOR EDUCATION IMPROVING HEALTH

Robert Kaplan, the chief science officer at the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality and a Roundtable member, recounted the June 4, 2014, meeting, “Understanding the Relationship Between Years of Education and Longevity,” which he had helped organize while serving in his previous position as director of the NIH Office of Behavioral and Social Sciences Research (OBSSR). The goals of that meeting, he said, were to convene a heterogeneous group of experts representing fields including education, economics, sociology, demography, epidemiology, psychology, and medicine; to identify gaps in knowledge; and to stimulate interest by funding agencies in developing a robust research agenda around the issue of education and life expectancy.

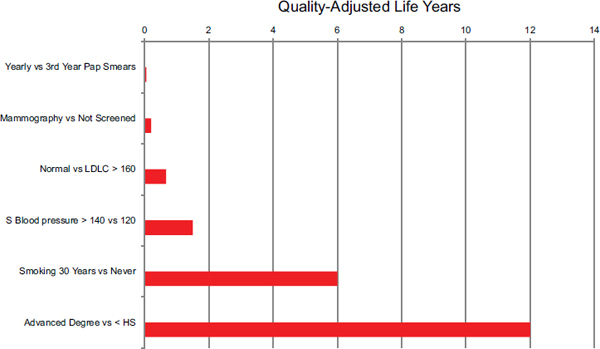

Kaplan began his summary by making the argument that educational attainment has a significant effect on life expectancy. When compared to other risk factors that people generally see as having a large impact on life expectancy, he said, educational level has a major impact on quality-adjusted life years by risk group (see Figure 1-1). For example, having a Pap smear once per year rather than once every 3 years increases quality-adjusted life years by, on average, a few days at most (Mandelblatt and Phillips, 1996). Having regular mammograms provides a benefit of about 1 month versus no screening at all (Gøtzsche and Jørgensen, 2013), while maintaining normal blood pressure adds about two-thirds of one quality-adjusted life year compared to having a systolic blood pressure of more than 140 (Clarke et al., 2009). The 6 years of quality-adjusted life years that one can gain by not smoking is much larger than these other factors (Clarke et al., 2009), but those who earn an advanced degree have an even

FIGURE 1-1 The effect of various risk factors on quality-adjusted life years. Data estimated from Whitehall 38-year follow-up study. NOTE: LDLC = low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; S Blood Pressure = systolic blood pressure.

SOURCE: Kaplan, June 4, 2014, NIH meeting presentation, adapted from Clarke et al., 2009.

greater edge over those who never graduated high school—as many as 12 quality-adjusted life years (Brown et al., 2012; Montez et al., 2012). Effects this large are too big to ignore, Kaplan said. Granted, these data did not come from randomized controlled trials (RCTs), Kaplan said, but in this case that does not matter. RCTs are needed to identify subtle differences, but the 12-year effect of differences in education is not subtle (see Box 1-1).

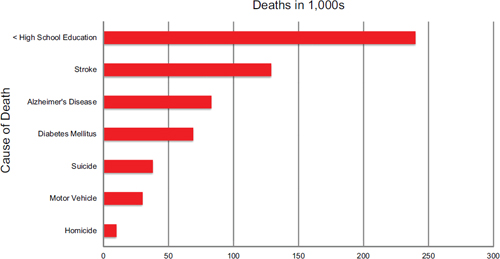

Another way to look at the effect of education on life expectancy is to examine the impact of various events on the number of lives lost (see Figure 1-2). These data also show a clear relationship between education and risk of premature death. In particular, having less than a high school education is associated with 240,000 lives lost annually, compared with 125,000 for stroke and up to 70,000 for diabetes (Galea et al., 2011).

Addressing the policy implications of educational attainment differences may be quite challenging. Kaplan highlighted the presentation of Neal Halfon, who described an approach to revising the nation’s health care system. In this talk, Halfon (2014) argued that there have been three eras in modern health care. The first, based largely on an industrial model, focused on acute disease and infections. In that era, hospitals were like factories where physicians worked and people with acute illnesses came to get “fixed.” The second era, which resulted from advances in science, particularly in epidemiology, placed an increasing focus on chronic dis-

BOX 1-1

How Different Interventions Will Improve Life Expectancy (in Quality-Adjusted Life Years), as Described by R. Kaplan

- Mammograms versus no mammograms → about 1 month of life

- Not smoking versus smoking → 6 years

- An advanced degree versus no high school diploma → 12 years

FIGURE 1-2 Deaths associated with low educational level in perspective.

SOURCE: Kaplan, June 4, 2014, NIH meeting presentation, death data from the National Vital Statistics System of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC, 2013a) and education estimates from Galea et al., 2011.

ease and attacking the risk factors associated with chronic disease. In this second era, health care moved from the acute care setting in hospitals into ambulatory care settings, and the goals shifted from simply reducing deaths to reducing morbidity and disability. The third era, which has not quite started, will place an increasing focus on achieving optimal health through investments in population-based prevention using a network model. Again, scientific advances will drive the transition between today’s health system and tomorrow’s, just as it did between yesterday’s and today’s.

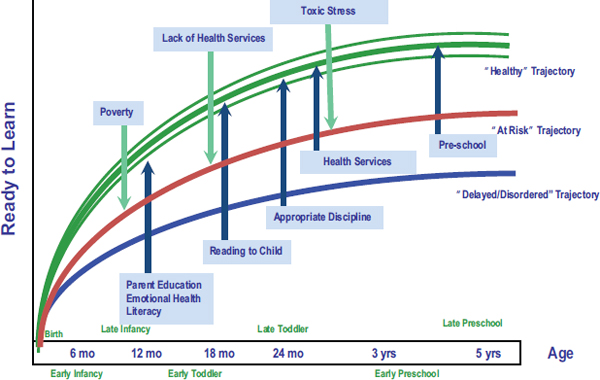

Halfon suggested that today there are a number of factors—parent’s lack of education and literacy among the biggest and earliest—that con-

spire to put some American children on a “delayed/disordered” developmental and health trajectory (Halfon, 2012) (see Figure 1-3). He said that pushing children back onto a “healthy” trajectory will require a number of interventions, many of which will involve education. An integral part of tomorrow’s health system will be to consider the entire life course of an individual, not just when someone presents with an illness.

Another presentation at the NIH meeting that Kaplan wanted to highlight was made by economist Favio Cunha, who, along with colleagues, has detailed the relationship between reading to children and the development of appropriate vocabulary (Cunha et al., 2010). Cunha argued that the well-known correlation between cumulative vocabulary and socioeconomic status at age 36 months has to do with allocation of parental resources, which includes both time and information. “This serves as a cornerstone for [many] other developmental processes,” Kaplan said.

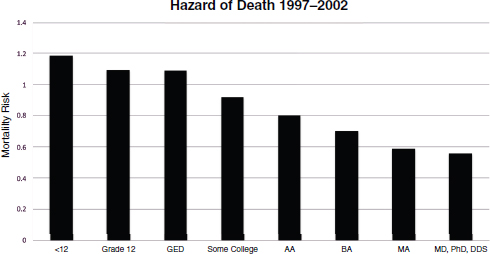

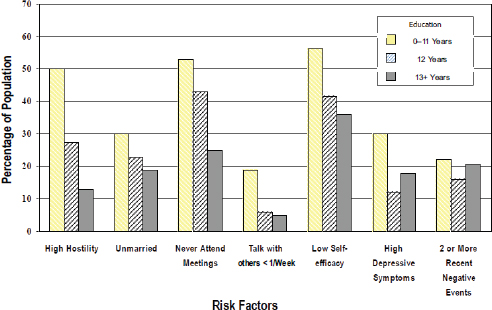

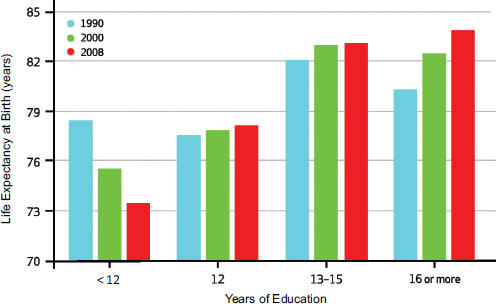

The heart of the NIH meeting was spent on the relationship between educational attainment and mortality risk (see Figure 1-4) and between education and morbidity risk factors (see Figure 1-5). Although the profound relationship between racial and ethnic group membership and life expectancy should never be downplayed, in fact the relationship between

FIGURE 1-3 Life-course health development: Reducing risk and optimizing protective factors.

SOURCE: Halfon, June 4, 2014, NIH meeting presentation.

FIGURE 1-4 Hazard of premature death by years of education.

SOURCE: Kaplan, June 4, 2014, NIH meeting presentation, adapted from Rogers et al., 2010.

FIGURE 1-5 Education and morbidity/risk factors.

SOURCE: House, June 4, 2014, NIH presentation, adapted from IOM, 2000.

educational attainment and life expectancy is stronger and more systematic (Herd et al., 2007; McDonough et al., 2000). The issue of whether these trajectories are changing over time received a great deal of attention at the NIH meeting (see Figure 1-6). The data suggest that the trajectories are changing, particularly among white women. While there have been declines in mortality risk among educated white women, there have been increases in mortality risk among women who do not attain a high school diploma. This is particularly the case for young white women (Montez et al., 2011). “I think that is something quite disturbing and needs attention,” Kaplan said.

Kaplan discussed data that he collected with George Howard and other colleagues showing that the relationship between educational attainment and life expectancy attenuates somewhat when the data are adjusted for demographic variables, further when an income adjustment is made, more when biological risk factors are considered, and more still when behavioral variables are added. He noted that there was a great deal of discussion among the demographers at the meeting as to whether this is a stepped relationship based on education level, where much of the gain in life expectancy occurs with post-high school education and then on through graduate education. More research is needed to confirm the functional form of the relationship.

FIGURE 1-6 Life expectancy by years of education at age 25 for white females.

SOURCE: Kaplan, June 4, 2014, NIH presentation, citing Olshansky et al., 2012.

Kaplan then discussed Sandro Galea’s presentation in which Galea argued that educational differentials, not educational attainment, are the real cause of these observed disparities. Galea hypothesized that variability in educational attainment across the population leads to diversion into other activities, particularly during adolescence, and that this diversion can have adverse effects on health outcomes years later (Galea et al., 2011). Galea noted that there is a need for more research on this relationship. Kaplan noted that in addition to the direct effects of education on individuals, there is a benefit obtained from a spouse’s educational attainment (Montez et al., 2009). For couples with differences in educational achievement, the less-educated spouse can experience up to approximately 3 years of benefit in life expectancy through association with a more educated spouse, he said.

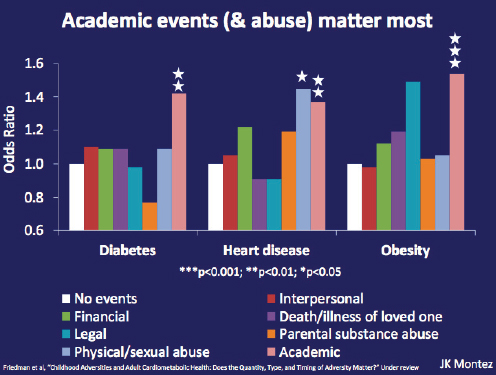

Adverse childhood events also have an impact on life expectancy (Montez and Hayward, 2014). Academic failures in childhood seem to have a particularly strong effect on being healthy as an adult, Kaplan said, and are remarkably strong predictors of disease outcomes in adult-

FIGURE 1-7 Adverse childhood events predict poorer adult health.

SOURCE: Montez, June 4, 2014, NIH presentation, citing Friedman et al., n.d.

hood (see Figure 1-7). The data also show that it is possible for a child’s educational achievements to overcome the negative impact of a parent’s low level of educational attainment.

A better understanding of the complex interplay between social factors—including education and health—will only come from more research in naturalistic settings, Kaplan said. One way to conduct such research would be to add health measures to some of the many intervention studies now being funded by the U.S. Department of Education and the department’s Institute of Education Science. One such study, for example, is looking at children selected at random by lottery to attend high-profile charter schools in Los Angeles. This study will track education performance, health habits, and the transition to additional education.

Kaplan noted that the participants at the NIH-sponsored meeting discussed three different hypotheses, regarding neuroplasticity, personality, and habits, to explain the relationship between education and health. The neuroplasticity hypothesis suggests that interventions must be in the first 1,000 days of life, while the personality hypothesis holds that conscientious people are more likely to live longer and complete more education (Friedman et al., 1995). The habits hypothesis posits that education is associated with the development of better health habits (Cutler and Lleras-Muncy., 2010). Current evidence, Kaplan said, does not clearly support any one of these hypotheses.

In order to advance this field, researchers will need to explore new sources of data, Kaplan said. One opportunity for testing these hypotheses can be found in the development of a data infrastructure and the availability of “big data,” such as the data that are being collected in Project Talent (Wise and McLaughlin, 1977). This longitudinal study of 440,000 high school seniors, who underwent testing in 1960 and were followed for 20 years, is now being analyzed to look for factors that influence mortality more than 50 years after the participants’ high school graduations. Other novel data sources include new data available from the Society of Actuaries and from the many states that can link school performance to detailed information about communities, teachers, and school characteristics.

Kaplan concluded his remarks by noting that the NIH-sponsored meeting brought scholars together from disciplines that do not ordinarily have contact with one another. He noted how little progress has been made to date in identifying knowledge gaps and said that the diverse group of experts at the meeting suggested several important new directions. The meeting’s effect on funding agency interest remains to be determined, Kaplan said, but he remains committed to furthering the dialogue on this topic.

This page intentionally left blank.