The first of the workshop’s panel sessions focused on how the education and health sectors could work together to address the health care needs of students and families and advocate for better health care for children. This session also explored ways of forming better connections between schools and local health care delivery systems. Charles Basch, the Richard March Hoe Professor of Health and Education at Columbia University’s Teachers College, described some approaches for reducing the health barriers that contribute to the achievement gap between low-income minority students and other students. Allison Gertel-Rosenberg, the director of national prevention and practice at Nemours, and David Nichols, program manager for Nemours Health and Prevention Services, then discussed ways of leveraging relationships between health and education sectors to improve health. A discussion moderated by Jeffrey Levi, the executive director of Trust for America’s Health and a Roundtable member, followed the presentations.

“No matter what we do to improve schools, no matter how effectively teachers could teach, how rigorous curricula may be, what assessments or standards are put in place, and how we organize schools, the educational benefits of all of these efforts are going to be limited unless the students are motivated and able to learn,” Basch said to start his presentation on

the power of health barriers to impede academic achievement. Addressing these barriers has largely been overlooked as a strategy for improving academic performance, he said, particularly among the most vulnerable of student populations. Basch noted that 40 percent of high school dropouts come from a mere 10 percent of the nation’s high schools.

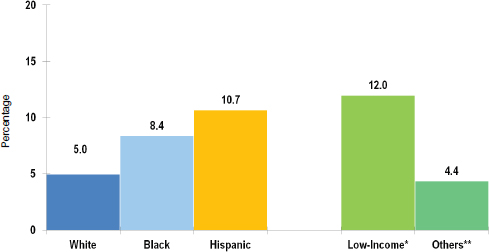

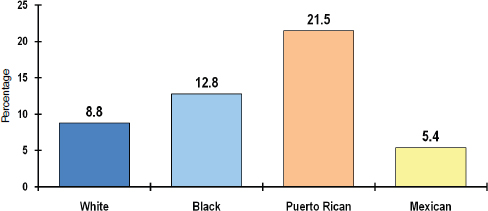

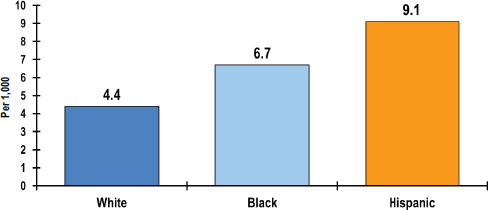

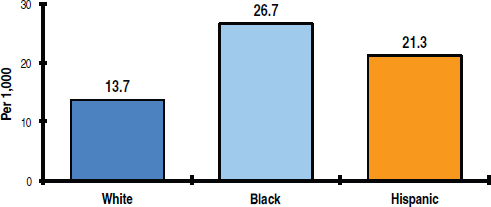

Schools cannot be all things to all people, and they must prioritize. Until now, schools have not been engaged in the nation’s health agenda because it has not been part of their fundamental missions. But given the connection between health and education and the impact of disparities on both health and educational achievement, those missions Basch noted, need to change to reflect this connection. “We have to have criteria for prioritizing,” he said. “I suggest considering the extent of disparities, the evidence of causal effects of health factors on education, and the evidence that we can do something about these problems, and based on those criteria, I am saying that these are a set of seven health problems—vision, asthma, teen pregnancy, aggression and violence, physical activity, skipping breakfast, and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)—that warrant consideration.” He further emphasized that mental and emotional health must be addressed thematically because it is a cause or consequence, or both, of the other problems. The precise makeup of this list can be debated, Basch acknowledged, but the central idea is that “there are multiple health problems that influence academic achievement and that all of these problems are highly prevalent and disproportionately affect low-income kids.” Vision problems, for example, affect low-income children more than others and black and Hispanic children more than white children (see Figure 3-1). The prevalence of childhood asthma is approximately 45 percent greater in black children and more than twice as high among children of Puerto Rican descent as compared with non-Hispanic white children, he said, noting that these numbers also demonstrate the importance of disaggregating the Latino population (see Figure 3-2).1 These same disparities are found in the statistics for poorly controlled asthma. Concerning aggression and violence, some 35 percent of high school students report that they have been in a physical fight over the preceding 12 months (see Figure 3-3),2 and almost 10 percent of Hispanic high school students in the United States say they have missed

_____________________________

1 More recent data show that the asthma prevalence for youth ages 5 to 14 has increased for whites and blacks. The asthma prevalence rate for black youth is twice the rate for whites (18.8 percent versus 9.4 percent). See Moorman et al. (2012).

2 The most recent Youth Risk Behavior Survey (2013) indicates that the percentage of high school students who report being in a physical fight in the past 12 months dropped from approximately 35 percent in 2011 to approximately 25 percent in 2013. Disparities among white students (20.9 percent) versus Hispanic students (28.4 percent) and black students (34.7 percent) persisted. See Kann et al. (2014).

FIGURE 3-1 Rates of visual impairment in the United States among persons 12 years or older by race/ethnicity and income.

NOTE: * Income below poverty level; 10 Income ≥ 2× poverty level.

SOURCE: Basch presentation, June 5, 2014, adapted from Vitale et al., 2006.

FIGURE 3-2 Asthma prevalence for U.S. youth ages 5–14 by race/ethnicity.

SOURCE: Basch presentation, June 5, 2014, adapted from Moorman et al., 2007.

1 or more days of school in the past month because they were afraid to be at school or to travel to or from school (see Figure 3-4).3

_____________________________

3 The most recent Youth Risk Behavior Survey (2013) indicates that more than 7 percent of high school students did not go to school at least 1 day in the past 30 because they felt unsafe to be at school or to travel to or from school. Rates among white students (5.6 percent) were lower than among black students (7.9 percent) and Hispanic students (9.8 percent). See Kann et al. (2014).

FIGURE 3-3 Percentage of high school students in the United States who were in a physical fight in the previous 12 months, by race/ethnicity.

SOURCE: Basch presentation, June 5, 2014, adapted from Eaton et al., 2012.

FIGURE 3-4 Percentage of high school students in the United States who did not go to school because they felt unsafe at school or on their way to or from school, by race/ethnicity.

SOURCE: Basch presentation, June 5, 2014, adapted from Eaton et al., 2012.

Although these statistics tell an old story, what is new is research that has been carried out over the past 10 to 15 years showing how and why these health problems affect academic achievement and educational attainment. Basch said that his research has identified at least five causal pathways: cognition, sensory perceptions, school connectedness and engagement, absenteeism, and temporarily or permanently dropping out of school. Cognition pertains to working memory and the ability to focus and sustain attention, shift from one task to another, solve problems,

and think critically, he explained. Sensory perception refers to being able to see and hear well. Basch noted, for example, that in New York City, vision screening of kindergarten children in the 60 lowest-performing elementary schools showed that 25 percent of the children failed the vision screen but, worse yet, that 60 percent of those children, or 15 percent overall, failed the vision test a second time when rescreened in first grade, indicating that they never got the care they needed for their eyes. “Imagine trying to learn how to read when you have hyperopia,” he said. “You are trying to distinguish and decode letters and words,” work that is hard for children with normal vision.

The third causal pathway, school connectedness and engagement, has to do with the extent to which the young people in school feel like they belong there and whether they feel like their peers and others care for them as people and as learners. “This is about human relationships,” Basch said, “and we know how important human relationships are in shaping our mental and emotional health. Indeed, that, in turn, confers benefits and opportunities for learning.” Regarding absenteeism, Basch said that about 20 percent of the 1.1+ million public school students in New York City schools are chronically absent, which means they miss a month or more of school each year. He noted that chronic absenteeism in the early grades, which can result from a health-related problem such as uncontrolled asthma, is highly predictive of high school graduation. And teen pregnancy and the consequences of ADHD—inattention and hyperactivity—are major contributors to dropping out of school.

“[E]ach of these causal pathways is influenced by multiple health problems simultaneously,” Basch said, adding that children living in poverty are, in fact, those who are most often affected by multiple concurrent health-related problems, a phenomenon with interactive and synergistic negative effects on school performance. School health programs must therefore focus on multiple health barriers simultaneously. “Unfortunately, that is not the way most of our evaluation research has been conducted,” Basch said. There are instead hundreds, if not thousands, of studies showing that breakfast alone does not have a consistent impact on achievement or that physical activity alone has merely a small or inconsistent impact.

So how can schools influence the health of the nation’s youth? “We actually know a lot about how to do this,” Basch said, noting the importance of developing a strategic focus on health problems that are known to have powerful effects on education. “We have to rely on evidence-based, scientifically generated knowledge, and we have to have efforts that are effectively coordinated.” The silos that separate health, education, and social services that Steven Woolf discussed in his presentation are a major obstacle to enacting coordinated efforts, Basch said.

An important challenge to addressing these issues on a national scale is that, unlike most countries, the United States has a decentralized educational system. “That said, I think the United States Department of Education can really have a powerful role to play because it can influence state education departments through a variety of ways,” Basch said. That influence can start with communicating the importance of the links between health and education to a national audience that includes not only school administrators but parents and community leaders. Basch said that the most successful programs will be those that involve the family, not just the children, and that provide financial support and incentives, technical assistance, and teacher development opportunities and involve the broader community in public–private partnerships.

The crux of the matter, Basch said, is that while there is a great deal of evidence identifying what needs to be done, “we are not doing what we already know how to do. We have to put into practice things that we have already learned through large investments in research and development.” On the other hand, he added it is imperative that widely used school health programs with no evidence of effectiveness be stopped. Basch said that colleges of education, medicine, and public health have an important role to play in preparing the next generation of teachers, school leaders, pediatricians, and others in the community to use evidence-based programs and to advocate for changes in the ways health care services in schools are reimbursed. Today, he said, Medicaid rules make it difficult to pay for health care services in schools even though schools are a powerful place to have an impact on the health of the nation’s youth. “That is where 50+ million young people in America go every day,” he said in closing.

LEVERAGING THE LINKS BETWEEN HEALTH AND EDUCATION

Nemours, an operating foundation that provides integrated child health services in the Delaware Valley and Northern Central Florida, promotes comprehensive, multi-sector prevention efforts, said Allison Gertel-Rosenberg. She and her colleagues at Nemours realized early on that no sector was going to be effective at addressing the health of children without taking a comprehensive approach that considered societal health issues and incorporated the child’s entire family. They know that when the health and education sectors work together and cross-reference each other, they can generate synergies that produce positive outcomes.

Nemours’ prevention-oriented strategy uses a socio-ecological model that looks beyond the individual to include a range of other factors that affect health outcomes at multiple levels and that takes a population health perspective rather than one focusing solely on an individual’s health. Gertel-Rosenberg acknowledged that taking such an approach

requires a shift in thinking from a health system in which providers are used to thinking about the patient sitting in front of them and not of the population as a whole. Nemours also came to realize early on in its work that strategic partnerships are important in assuring that a program has the greatest possible impact in effecting the desired policy and practice changes and that it leverages limited resources more effectively. Nemours also concluded in its planning activities that social marketing would be important for creating and accelerating the social policy and behavioral changes that would be required in order to have a truly transformative impact on health at the population level.

To illustrate how Nemours is turning these ideas into action, Gertel-Rosenberg discussed two programs, one focused on early literacy, the other on healthy eating and physical activity. Nemours’ BrightStart! program focuses on early childhood literacy and creating materials and services targeted at young children who are at risk for having reading problems. The goal, she explained, is to effectively teach young children to read. This program goes beyond the child, though, and aims to help parents, teachers, health care providers, community leaders, and policy makers understand the critical actions that promote reading success for all.

One important element of BrightStart! is screening all 4- and 5-year-old children using a quick, psychometrically sound measure of reading readiness in order to identify at-risk children. Those children then receive a 20-lesson, small-group instructional program, followed by rescreening. A 4-year, cluster-randomized study conducted in preschools and child care centers screened more than 13,000 children, of whom 3,300 received the BrightStart! intervention. Two-thirds of the children moved to an age-appropriate range in reading readiness skills after the intervention. “The great part about this is that we are also seeing these gains sustained as the children move into grade three,” Gertel-Rosenberg said. “It is both those short-term gains and those longer-term gains that we are looking for from this intervention.”

She explained that after each school year her colleagues used the data they collected to modify the intervention to respond to the weaknesses that the data had identified. The primary weakness identified by the data involved the need to do more work to enhance phonological awareness in young children. She added that additional research is needed to develop approaches to reach those children who are not responding to the treatment.

The second program Gertel-Rosenberg discussed was the National Early Care and Education Collaborative Initiative, which is funded through a cooperative agreement with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). This program focuses on changing systems and

practices at early care and education centers in order to promote healthy eating, physical activity, and breastfeeding and to decrease time spent watching television and on the computer. The program consists of five learning sessions plus homework given over the course of the year. The in-person sessions are spaced approximately 6 to 8 weeks apart to provide enough time for the leadership teams to complete their “homework” with early childhood education program staff.

The program’s first cohort, which includes 7 partner organizations in 6 states, and more than 500 early care and education programs serving 52,000 children, is finishing its fifth learning session, and Gertel-Rosenberg said she expected to have the first data available on the impact of this intervention in the fall of 2014. Three-quarters of the children enrolled at these early childhood education centers are preschoolers, ages 37 to 59 months. Two out of five of the centers participate in the Quality Rating and Improvement System, and two out of three participate in the Child and Adult Care Food Program. All but 2 percent of the programs serve food, and two-thirds of the centers prepare the food they serve, which, Gertel-Rosenberg said, provides the opportunity to influence how food is prepared for a large group of children.

Gertel-Rosenberg said she and her colleagues have already learned some important lessons about what is needed to have an effect, and not just at the center level. At the state level, organizations need greater capacity and they need to start thinking more about weaving projects into existing initiatives. Gertel-Rosenberg and colleagues also learned that it is important to ask center staff to become leaders, to have a trained workforce, and to provide staff support through coaching. They also discovered that there are no perfect trainers because those who are strong in early childhood education are usually weak in health knowledge, and vice versa. Early data have also shown the challenge of getting families to agree with and commit to the changes that they need to make in order to support what their children are learning in the program. State organizations have reported that personal contact and relationships with early childhood educators are critical for engagement and participation and that some providers need coaxing to implement these changes.

Gertel-Rosenberg concluded her presentation by saying that her team is evaluating this initiative comprehensively and is starting to roll out the initiative’s second cohort in two phases. In the first phase, she said, the program will be extended to several new states, while the second phase will add new centers in the original six states.

Gertel-Rosenberg’s colleague, David Nichols, spoke about three school-focused initiatives that Nemours Health and Prevention Services is managing. The organization started this work, he explained, when the U.S. Department of Agriculture issued new regulations mandating that

schools create a wellness policy and a wellness council. “We saw that as an opportunity to work with school districts to change the way they look at students and to start to impact that and help them move to thinking more about students’ health instead of just students’ academic performance,” Nichols explained. He noted that one of the effects of demanding that educators focus more on testing has made children’s health a low priority.

The first initiative he described is called Making School a Moving Experience, which Nemours started in 2009. “After working with school districts for several years on wellness policy, our school district leaders in Delaware were telling us that they could not figure out how to change the food policies in their school or how to change the physical activity patterns that children had in school,” Nichols said. “They saw those as something important, but something beyond their capacity to do given their other requirements.” Nichols’ approach was to identify schools that were tackling these two problems and using them as exemplars to showcase to school districts.

The goal of this initiative, which was funded by a Carol M. White Physical Education Program grant from the U.S. Department of Education, is to support partner schools in providing students with at least 150 minutes of physical activity per week. Nichols and his colleagues work with schools to help them create their own combination of physical education, classroom activities, recess activities, and other adaptations to the school schedule in order to meet this goal. The Nemours team suggests some evidence-based practices that each school could undertake, though Nichols noted that there are not many evidence-based programs available. Two that he identified were the Coordinated Approach To Child Health (CATCH) program developed at the University of Texas and the Take 10! program from the International Life Sciences Institute (ILSI) Research Foundation. Once each school develops its plan, the Nemours team develops materials such as window decals, signs, pins, and slides to communicate the plan to staff. Staff then receives multiple onsite and offsite training sessions, provided as part of the Making School a Moving Experience initiative. Nichols and his team monitor implementation and make suggestions for adjusting the original plan. He said that he views the role of Nemours as providing a supportive atmosphere and technical assistance that help schools make these changes in a way that fits their individual requirements and circumstances and that give each school ownership of its particular program. “That proved to be very important,” Nichols said.

By the end of the U.S. Department of Education grant, Nemours had partnered with 13 out of 15 school districts in Delaware that have elementary grades and had gotten 74 public elementary schools to incorporate 150 minutes of physical activity into the school week. More than 40,000

students participated in the program, and more than 2,000 teachers and staff members were trained to provide physical activity. The result was that student physical activity increased from an average of less than 100 minutes per week to around 200 minutes per week, Nichols said, and approximately 138 of those minutes involve moderate to vigorous activity. “We didn’t meet our ‘150 moderate to vigorous’ goal, but we made great strides,” he said.

The second program that Nichols discussed used a CDC community transformation grant to focus on physical activity, active living, nutrition, and behavioral health. This initiative was designed to help schools coordinate the resources that they already had but that were not well-coordinated. Using available tools, the Nemours team helped schools evaluate their wellness policies and understand the activities that should be undertaken in light of the opportunities available for improving both health and education. The team also helped create nutrition promotion plans that included such things as food of the month and taste testing and that used behavioral economics to promote increased consumption of healthy foods and decrease plate waste. Nichols said that when this grant ends in late September 2014, there will be a population of school leaders who understand wellness policy, who see the benefits of it and understand what it should look like, and who are committed to implementing strong wellness policies in their schools.

The third program Nichols described, the Student Health Collaboration, is designed to transform care coordination by collaborating with school nurses. School nurses, he said, provide essential medical care to children while they are in school. Many of these children have complex medical conditions that require careful management and care coordination. Unfortunately, school nurses today are not routinely considered as part of a child’s care team. Recognizing this problem, a multidisciplinary team was formed to develop a way to facilitate the exchange of medical and educational information among school nurses, primary and specialty clinicians, and families with the goals of improving communication between school nurses and Nemours clinicians and enhancing nurses’ access to students’ health information and medical records.

Through this effort, 100 percent of Delaware’s public school districts, 64 percent of its charter schools, 24 percent of its private schools, and 48 percent of its diocese schools have completed partner and user agreements with Nemours. More than 1,500 students with chronic or complex conditions are now enrolled, as are 235 school nurses. Nurses report that because of the closer ties to clinicians that have developed, they are making better use of their time and now find it easy to get the medical and treatment information they need for their students. In the process, Nemours learned that having integrated care champions is a key to suc-

cess and that it is important to use systems that are already in place rather than building new ones. Parental feedback on communication products has proven important, as has the opportunity for school nurses and clinical staff to have face-to-face meetings. Going forward, the main focus of this program will be to ensure that all school nurses in Delaware have the opportunity to participate and also to use quality improvement measures to improve health outcomes for all students and improve health communications betwen the families and health care providers. Nichols and his team are currently fielding a pre–post survey with parents and guardians to measure perceived changes in health-related quality of life, parent opinions about the program and their child’s health, and days of work missed due to children’s illnesses.

The session moderator, Jeffrey Levi, started the discussion by describing a few of the key messages he took away from the presentations, the most important of which was that these are multi-factorial problems that require multi-factorial solutions. He also mentioned the importance of breaking down silos, and he said he thought that Roundtable members need to consider how they can add to conversations about strategies for dismantling silos. There is value in thinking across generations when thinking about health and education, he said, so that even if the focus starts with children, it must eventually expand to include families and communities. There is also a tremendous opportunity for the Roundtable to promote ways to educate educators and clinicians about ways to collaborate and sustain team-based care that broadens the notion of who should be part of that team.

Levi then asked the panelists if they had any data yet showing that these programs are capable of improving the bottom line of health systems. Both Nichols and Gertel-Rosenberg replied that it was still too early to see those kinds of gains, but each described some of the tangible benefits that they are seeing. Nichols noted that one component of the Make School a Moving Experience initiative was to assess children in fourth grade as being either fit or unfit, and the data showed that students who were fit attended a remarkable 30 days of school more per year. “They did markedly better on their state tests and there were few discipline problems,” Nichols said (Gao et al., 2011). Gertel-Rosenberg said that the collaboratives in Delaware that were focused on healthy eating induced 81 percent of the enrolled centers to make changes to both physical activity and healthy eating policies or practices that were sustained at least 1 year after the collaborative program ended, while the other 19 percent of the centers made changes to either healthy eating policies and practices

or physical activity policies and practices that were sustained for at least 1 year after the program ended. “The idea is that if we are changing the context of the environment, whether that is through the availability of more water or low-fat milk or increased physical activity,” he said, “that we are increasing the opportunities for healthy behaviors to take place and that in the long run would hit the students themselves.”

Basch responded to Levi’s question by describing a collaboration he has with the Children’s Health Fund that provides mobile delivery of health care to about 400,000 of the nation’s most vulnerable children and families. This organization, he explained, came to the conclusion independently that it could have a bigger impact by helping children succeed in school and in life. In the fall of 2014, the collaboration will launch the first phase of an initiative called Healthy and Ready to Learn. This initiative will start in New York City and be rolled out through a network of approximately 200 schools located in some of the most high-poverty communities across America.

One example of the barriers that this initiative will attempt to address is the lack of follow up after a failed vision screen. Each student will get an onsite exam with an optometrist, and students with a refractive error will be provided with two pairs of glasses, one each for home and for school. Students will receive replacement glasses when their glasses are lost or broken. In addition, this collaboration with New York City public elementary schools will work to educate teachers about the need for their students to use their eyeglasses and work with parents and guardians to encourage children’s use of eyeglasses at home. This project is also going to focus on identifying children with poorly controlled asthma, connecting them to a medical home and helping them receive the medications necessary to get their asthma under control. It will also be important, Basch said, to implement social-emotional learning programs that can help produce permanent behavior changes. He noted that there is a list of social-emotional learning programs for which there is an impressive body of evidence available at the U.S. Department of Education’s What Works Clearinghouse and the Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning.4

Basch said that the collaboration with the Children’s Health Fund will also implement physical activity programs, which the education community finds attractive because of the evidence showing that short breaks in the morning and afternoon improve children’s on-task learning

_____________________________

4 For more information see the U.S. Department of Education’s Institute of Educational Sciences website at http://ies.ed.gov/ncee/wwc (accessed August 4, 2014); also see the Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning (CASEL) website at http://www.casel.org (accessed August 4, 2014).

behavior. “That is what school administrators pay attention to,” Basch said. They will also be working to increase participation in school breakfast programs, an important task given that New York City has one of the lowest participation rates of large cities in the United States. Parent outreach and education will be a critical component of this effort, as will professional development for teachers. Basch commented that principals in these schools already recognize the need for these programs and are both excited about and open to participating. They understand that certain health problems affecting children in their schools are undermining and jeopardizing the other investments that are being made to foster educational attainment.

Basch said that the Children’s Health Fund is trying to build a database that will integrate education and health-related data to help determine which children need what services when. This database will also be valuable in evaluating programs to determine if the changes they produce lead to improvements in health and education. Levi said that having the data be bidirectional so that health care providers know what is happening academically with the children under their care will be an important challenge to address. Basch replied that there is also work under way to get pediatricians to start asking questions relevant to school performance, such as whether parents are reading to their children and if their children are happy at school.

Sanne Magnan from the Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement asked Gertel-Rosenberg if there had been a control group in the BrightStart! experiment. Gertel-Rosenberg replied that schools were randomly assigned to intervention or control groups based on zip code and the percentage of children receiving financial subsidies. The timing of the introduction of the interventions at schools were also staggered, and there was no difference between interventions delivered in the spring and those delivered in the fall. Debbie Chang added that BrightStart! was first tested in Jacksonville, Florida, and that it has since spread across the entire state. Nemours now has a partnership with Kaplan Early Learning Company and is planning to spread the program nationally.

Phyllis Meadows from The Kresge Foundation and the University of Michigan said that from her perspective all of these issues were debated in the 1950s, “and yet here we are again fighting for the same policies to feed our children, to make sure that there is community use of schools so that we can have extra activities for our children, that we can have access to supportive referral resources within the schools.” Given this situation, she asked the panelists if they had ideas on the kinds of policies needed to make such efforts more sustainable so that the same situation does not repeat itself in another 50 years. “What kind of sustainable policies do we need to be thinking about,” she asked, “and how do we structure those?

Are there some policies that we need to sunset, either on the educational side or the health side that are really not advantageous to this agenda?”

Basch responded that these questions demonstrate that science is not the only thing that drives policy. “Indeed, ideology, political will, and economic factors have a pervasive effect,” he said, “and one thing that would address these concerns is to have a strategic plan for the nation that invests in shaping the lives of youth through schools.” Healthy People 2020 is a useful blueprint that creates accountability for the national health agencies, he added, and a strategic plan for the nation’s schools could provide a similar accountability structure to keep these issues on the agenda, he added. Basch said that he agrees with Woolf’s assessment that better communication efforts are needed to inform other audiences—particularly members of the business and industry communities, those who make economic policy, elected officials, and members of the media—of the importance of the connection between health and education. In particular, he said, efforts should be made to elevate the discussion above health or education outcomes and to frame it in terms of economic security and the vitality of American democracy.

Robert Kaplan of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality remarked that the educators he talks to all say they are doing the best that they can, given all of the programs that they are responsible for administering, and he asked the panel members what they would say in response to a principal or school superintendent. Basch answered that when he speaks with education leaders, he emphasizes that if they do not address these health barriers to learning, they will jeopardize the educational benefits of all the other investments they are making. “They seem to understand that more and more,” Basch said, adding that there is increasing recognition of the educational significance of health barriers to learning throughout the education community, from the secretary of education to the state superintendent to principals, teachers, and parents. He added that school leaders need help setting priorities, which is why he suggested a conversation about a strategic plan. Levi said that the development of good metrics and report cards might warrant some attention as well, and Basch strongly agreed.

Mary Pittman of the Public Health Institute asked Nichols to expand on how data are exchanged between schools and health providers, and Nichols said that such a two-way exchange does not occur. “Honestly, the schools are not sharing medical information with us,” he said. “We are sharing medical information with them, but they do not have the systems in place yet to share back with us.” Nemours is able to share data with the schools by using an add-on tool to its medical records system that allows information sharing with physician groups and community doctors. He noted that an assumed conflict between the regulations in the Health

Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) and the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act turned out to be an easy obstacle to overcome.

Pittman also asked how school nurses were funded. Nichols said that in Delaware school nurses are part of regular school funding. “Every school is expected to have a school nurse,” he said. “That is part of the teacher count.”

This page intentionally left blank.