6

State and Local Collaboration Between the Health and Education Sectors

The workshop’s third and final panel discussion featured three presentations on the conditions under which state and local collaboration between health and education can work. Loel Solomon, vice president for community health at Kaiser Permanente, discussed some models of state and local collaboration based on his organization’s work in eight states and the District of Columbia. Kent McGuire, president and chief executive officer of the Southern Educational Foundation, described the regional disparities that exist regarding poverty and health outcomes and the policy challenges at the state and local levels for those interested in addressing those disparities. Terri Wright, director of the Center for School, Health, and Education at the American Public Health Association (APHA), discussed her organization’s focus on partnering with school nurses to reduce dropout rates. A discussion moderated by Solomon followed the presentations.

MODELS OF STATE AND LOCAL COLLABORATION BETWEEN HEALTH AND EDUCATION

Kaiser Permanente is the nation’s largest nonprofit private health care organization that both delivers care and offers a health plan, Solomon told the workshop participants. Kaiser Permanente has both the incentives in place and the mission to provide high-quality, affordable care and to improve the health of the members in the communities that it serves, he said. Of particular relevance to this workshop, Kaiser Permanente has a

long history in early childhood education and in schools, starting with the early childhood care centers that Henry J. Kaiser established, at the personal request of Eleanor Roosevelt, in the Kaiser shipyards that existed during World War II. These centers, which were established to support the women who worked in the shipyards, offered well-child care and immunizations.

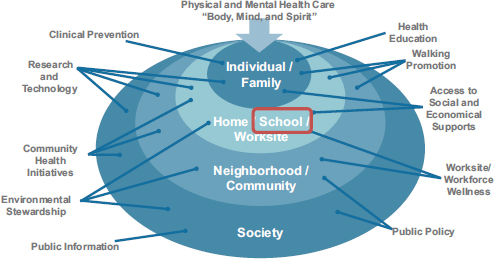

Over the past 25 years Kaiser Permanente has run an education theater program that has performed for some 10 million children, and over the past decade Kaiser Permanente has been engaged in community health initiatives that feature multi-sector collaborations, including collaborations with schools. Over the past couple of years, Solomon said, the organization has been trying to determine how best to integrate these different programs and its assets with a deliberate focus on schools. The logic for this focus is that 20 percent of Kaiser Permanente members spend most of their days in school and that there is a growing amount of research indicating that schools are the hub of health. “Schools, as the heart of health, represent an important civic anchor,” Solomon said. “They can generate health, not just for the school, but for the entire community, and there is a growing evidence base” that school-based interventions work. Solomon added that Kaiser Permanente’s total health perspective (see Figure 6-1), which looks for ways to affect health in a positive way outside of its medical facilities, is another driver of the organization’s focus on schools, in alignment with the organization’s overall priorities.

Kaiser Permanente’s school strategy primarily stresses health goals, but it also takes into account the fact that those are not the goals that are most important to its education partners. As a result, the Thriving Schools program aims to produce, in addition to health benefits, the benefits in academic performance, school achievement, and workforce productivity that are of most importance to school leaders. The program’s areas of focus are promoting healthy eating and active living—two areas of competence for Kaiser Permanente that are a major focus of school wellness policies—and also improving school climate, including addressing behavioral issues and promoting the social and emotional health of students. The targets for this work include students, staff and teachers, and all of the other people who are engaged in promoting student health within schools during the day.

Solomon remarked that Kaiser Permanente is trying to involve its entire workforce to serve as volunteers who can bring their varied experiences into the schools. For example, senior leaders in its Oakland headquarters are working with the Oakland Unified School District on strategic planning and project management issues that are important for the school district. In addition, Kaiser Permanente is partnering with other organizations, such as the Alliance for a Healthier Generation, the Safe

FIGURE 6-1 Kaiser Permanente’s total health perspective aims to activate the organization’s assets at all levels to improve the health of the communities it serves.

SOURCE: Solomon presentation, June 5, 2014.

Routes to School National Partnership, and the School-Based Health Alliance, to build on their expertise and leverage Kaiser Permanente’s competencies. For example, Kaiser Permanente is working with the Alliance for a Healthier Generation and its program managers to deliver intense interventions across its partner schools and is also working with the Safe Routes to School National Partnership to support physical activity at or on the way to and from school. Kaiser Permanente’s collaboration with the School-Based Health Alliance is looking at ways in which school-based health centers could become a more effective driver of school wellness.

To date, out of the 14,000 schools located in its service areas, Kaiser Permanente has engaged some 1,000 schools in physical activity programs and about 250 schools in a joint program with the Alliance for a Healthier Generation. Solomon said that the Los Angeles Unified School District, the nation’s second largest school district, has recently joined the Thriving Schools program and that he and his colleagues are now putting in place an evaluation that will provide solid baseline data so that the program will be able to measure success and drive improvement efforts.

Based on Kaiser Permanente’s experience in cross-sector collaboration, Solomon offered a few lessons that he and his colleagues have learned. He prefaced those lessons with the comment that both the education system and the health system are undergoing incredible transformations today that can cause organizations either to become narrowly

focused, which is not a good environment for collaboration, or to reach out to others to get new ideas and new partners. “We need each other so much more than ever,” Solomon said. “Health needs education to deliver prevention and bend the trend in a sustainable way on health care cost growth. Education needs health to have kids that are ready to learn.” Turning back to the lessons learned, he said that those who are interested in creating the necessary conditions for successful cross-sector collaboration must start with and be focused on areas where there are convergent strategies even when the goals are divergent. It is important, too, to find people who are “bilingual in health and education and to support them on the ground,” Solomon said. “These local champions are so incredibly powerful. We need to nurture them, and we need to provide sustainable funding streams for them.”

Another lesson Solomon offered is that it is important to mind the gap between knowledge and practice. “We have found very few people in education [who] don’t understand the connection between health and education,” he said. It is all a matter of making “it easy for educators to implement those practices that are evidence-based and that are going to make a difference.” Also critical is the need to align measurement and accountability systems. “That is what institutionalizes the incentives,” Solomon said. Imagine the opportunities for natural experimentation, he said in conclusion, if there were educational data systems that included longitudinal core health measures.

REGIONAL DISPARITIES IN HEALTH AND EDUCATION

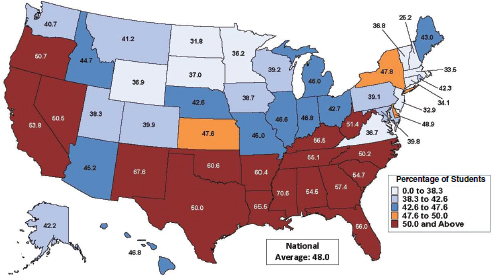

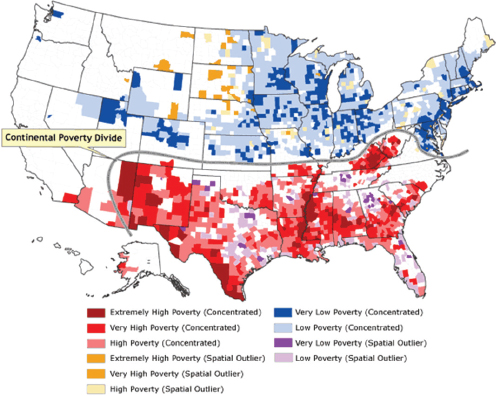

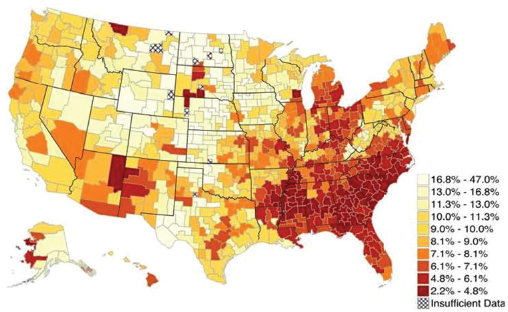

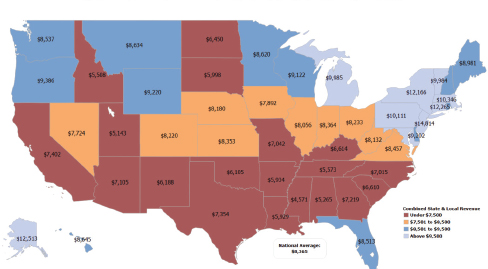

Kent McGuire began his presentation by showing a series of maps of the United States that illustrated the regional disparity in the percentage of low-income students enrolled in public schools (see Figure 6-2). These maps showed rates of persistent poverty (see Figure 6-3), social mobility (see Figure 6-4), obesity rates (see Figure 6-5), life expectancy (see Figure 6-6), teenage births (see Figure 6-7), graduation (see Figure 6-8), and state and local funding of public schools (see Figure 6-9), and by comparing them one can see a clear connection among poverty, poor health outcomes, graduation rates, and school funding.

“The states that we worry about the most,” McGuire said, “are the ones that are persistently in extremely high poverty,” particularly given the dire situation that these figures show in aggregate. “[The figures] pretty much speak for themselves,” he said. “Not too surprisingly, the lowest high school graduation rates are in the same geography.” These are also the same areas where the least amount of money is spent on public school education, where life expectancy is lowest, where childhood obesity is most prevalent, and where teen pregnancy rates are the highest, he noted.

FIGURE 6-2 Percentage of low-income students in all public schools, 2010–2011.

SOURCE: McGuire presentation, June 5, 2014, citing Suitts, 2013.

FIGURE 6-3 Rates of persistent poverty.

SOURCE: McGuire presentation, June 5, 2014, citing Holt, 2007.

FIGURE 6-4 Social mobility for a generation of poor children.

SOURCE: McGuire presentation, June 5, 2014, adapted from Chetty et al., 2014.

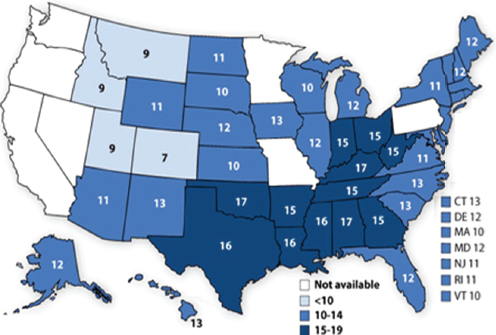

FIGURE 6-5 Obesity rates for high school students.

SOURCE: McGuire presentation, June 5, 2014, Eaton et al., 2012.

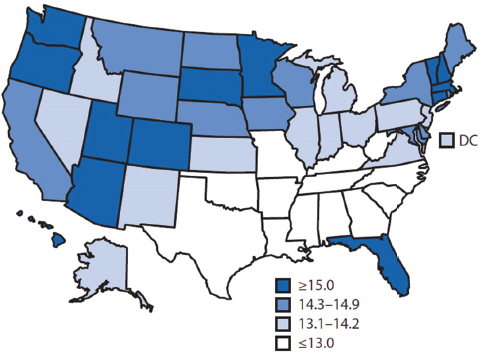

FIGURE 6-6 Life expectancy at age 65.

SOURCE: McGuire presentation, June 5, 2014, citing CDC, 2013b.

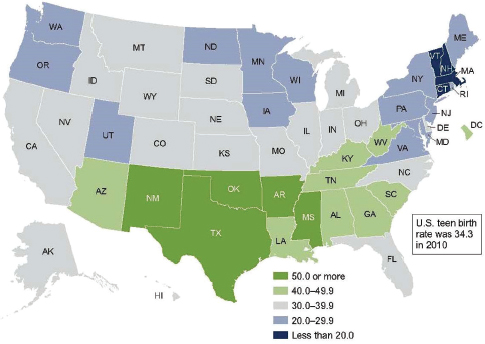

FIGURE 6-7 Rates of teenage births.

NOTE: Birth rate for women aged 15–19, by state, 2010.

SOURCE: McGuire presentation, adapted from Hamilton et al., 2012.

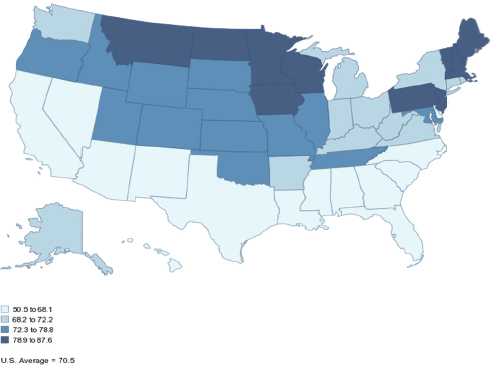

FIGURE 6-8 High school graduation rates, 2009.

SOURCE: McGuire presentation, June 5, 2014, citing National Center for Higher Education Management Systems, 2014, adaptation of National Center for Education Statistics common core data.

FIGURE 6-9 State and local funding of public schools.

NOTE: State and local spending per student for K–12 education, 2011.

SOURCE: McGuire presentation, June 5, 2014, adapted from U.S. Census Bureau, 2012, by the Southern Education Foundation.

With that as a background, McGuire provided several examples of successful collaboration and interaction between the health and education communities aimed at remedying the unacceptable situation illustrated by the maps. One example was how school report cards are incorporating an increasing number of health and wellness indicators, which goes hand in hand with the increased activity in screening and fitness assessment in schools. Louisiana, he noted, asked for Medicaid waivers so that it could pay for school-based health services. The systems that are interacting and collaborating closely, he said, are those with fewer resources. “They have more incentives and interest in trying to figure things out.”

On the other hand, he said, it is uncommon to find examples of systematic thinking, which can be hard to sustain when reliable funding is lacking. It is important, McGuire said, to get school systems to start to think in terms of evidence-based interventions. “We have got some maturation to do on the education side in that respect,” he said. Other items on his to-do list are preparing teachers and principals to promote health and wellness and arming schools and school districts with effective, evidence-based strategies. More needs to be done to incorporate health and wellness into school metrics and accountability policies and to better integrate school and health care data systems so that student academic records are merged with health data, McGuire said. He also noted that most of the attention paid to data systems in public schools is focused on the alignment of administrative records for preparing school report cards. “It is not for decision making and continuous improvement,” he said. “That is a very different motivation.”

Describing actions he would like to see, McGuire suggested that existing state Medicaid plans could be tuned to adapt to the opportunities and challenges of paying for services in school districts. He also thought that integrating student academic and medical records should be a top priority for action because it would create an opportunity to conduct experiments in conjunction with coordinated care networks in order to better understand how various programs are working. There is also an opportunity to create more sustainable policies by better integrating support for students and families. McGuire said that the charter school movement could be an ideal environment in which to innovate but that, for the most part, this is not happening.

McGuire also listed some policies that should be retired. First, he said, there needs to be a better dependent variable than standardized test scores for judging the efficacy of educational programs. “If we could focus on the whole child, that would open up to all of the things you would need to take into consideration in order to get the learning outcomes that we are really interested in,” he said. One challenge, he added, is that too many reformers and political leaders are unsure that the current

educational system can accomplish anything and so are reluctant to add new responsibilities and provide new resources to improve the system. He also said that the focus on test scores as a means of holding teachers and schools accountable is misdirected. “Accountability is not a capacity-building strategy for schools,” he said.

In his concluding remarks, McGuire emphasized that the disparities and gaps in income that he illustrated with his series of maps and the correlations between those gaps and health and wellness are real, and he said that it is time for the health community to step to the podium and argue for systemic change. “If there was ever a leadership moment for folks outside of the education system to underscore how important it is for that system to actually work and then offer a range of ideas to generate better outcomes, I would say that now is that time,” McGuire said. He asked the Roundtable to drill more deeply into ideas and strategies that might give rise to broad-scale systemic change to go along with the efforts being funded largely by philanthropies to create pilots and generate evidence.

REDUCING DROPOUT RATES TO IMPROVE HEALTH OUTCOMES

As a preface to her remarks, Terri Wright said that public health, population health, and health care have distinctive roles that are complementary. “One is an outcome, and two are processes and products that can lead to that outcome,” she said. She then provided some background information about the Center for School, Health, and Education, which was established in 2010 at APHA to focus on, and elevate, dropout prevention as a public health policy. She said that APHA has a policy in place that speaks specifically to public health and education and to the need to work collaboratively across sectors to improve high school graduation rates as a means of eliminating health disparities. The Center for School, Health, and Education is a focal point for APHA’s work at the intersection of public health and education. She also commented that it was significant that high school graduation was as an explicit goal in Healthy People 2020.

Wright briefly reviewed the reasons that had already been given for why high school graduation matters: Dropouts experience shorter life expectancy and are more likely to suffer from chronic illnesses such as cardiovascular diseases, cancer, infections, lung disease, and diabetes; dropouts earn 41 percent less than someone with a high school diploma and are 28 percent less likely than college graduates to have insurance coverage; and dropouts are less likely to be enmeshed in social conditions that promote health as an adult. Wright also reiterated the oft-stated

message that for children and adolescents, health and education are two sides of the same coin.

Wright said that she and her colleagues at the Center for School, Health, and Education believe that it is possible to make a difference for all youth through school-based health care because schools are the only institutions that can reach nearly all youth. In that respect, she said, schools are in a unique position to improve both education and the health status of young people throughout the nation. With that in mind, the center works to advance school-based health care as a comprehensive strategy for preventing school dropouts and improving graduation rates as an interim step toward adult health.

“Why school-based health centers?” Wright asked. “Because they have a track record of dealing with the social circumstances associated with educational success.” They also have a track record of dealing with some of the social experiences associated with dropping out, such as school violence and bullying. In addition, school-based health centers explicitly focus on risky behaviors and the dangerous health outcomes associated with adolescents, and they do so as a confidential, nonjudgmental, trusted source of expertise in the school building upon which both students and school personnel have come to rely.

Wright said that the primary reasons that male students drop out of school are disciplinary issues, the need to earn an income, poor academic performance, absenteeism, and disengagement from school. For females, the number one reason for dropping out is pregnancy. Other reasons that females drop out are parenting and caregiving responsibilities, the need to earn an income, and harassment at or on the way to or from school. The center focuses on a public health approach to addressing these factors and uses school-based health centers as trusted hubs for making that happen. These school-based health centers play a number of other key roles, including using assessments to identify the factors involved in students dropping out, responding to those factors, being the catalyst for raising awareness of the important issues that the assessments have identified, and then bringing the resources into the school to address those issues (see Figure 6-10).

School-based health centers represent a successful example of state and local partnerships between the health and education sectors, Wright said. At the state level, health departments and education agencies may work in partnerships, along with the Medicaid agency, to provide financial resources. In some cases, these financial resources can be state or federal funds that are used directly or indirectly to address these issues in local schools. State health and education departments also provide guidance and technical assistance. Some of these programs, Wright said, are funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s coordinated

FIGURE 6-10 The Center for School, Health, and Education’s strategic model for dropout prevention.

SOURCE: Wright presentation, June 5, 2014.

school health programs, which put people in state health and education departments with the explicit mandate of collaborating together to address issues at the local level that can affect the health and success of children at school.

At the local level, Wright continued, there are partnerships between local school districts and health agencies in which the school districts pay for school nurses, who are school employees, while the health providers in school-based health centers are sometimes funded by large hospitals or health systems. In some cases, the funding for school-based health care comes from a patchwork of private and public sources that come together in a collaborative way to meet the needs of children and adolescents through the schools, Wright explained.

There is a variety of evidence supporting a central role for school-

based health centers, Wright said. Studies show, for example, that they attract harder-to-reach populations, particularly racial and ethnic minorities and males. And they do a better job of getting these hard-to-reach populations the services they need, such as mental health care, and of conducting risk assessments and early interventions. Data also show that adolescents are 10 to 21 times more likely to come to a school-based health center than to a community health center for mental services. “Why?” Wright asked. “Because it is in the school building, which makes it easier for them to do.”

Other evidence shows that sexually active adolescents are more likely to accept and use contraception when it is provided by a school-based health center. Furthermore, students, teachers, and parents with access to a school-based health center rated academic expectations, school engagement, safety, and respect significantly higher than did those in schools without a health center. “The mere presence of a school-based health center positively impacts the overall school climate and learning environment,” Wright said.

Students who have access to school-based health centers have lower rates of absenteeism and tardiness and higher grade point averages than students in schools without a health center. African American males in particular are three times more likely to stay in school if they have access to a school-based health center. There is even preliminary evidence that school-based health centers have a positive impact on school suspensions.

Wright concluded her presentation by discussing some sobering statistics collected in a school-wide assessment in one high school and one middle school in an impoverished U.S. city. This assessment was conducted in a manner that allowed the students to truly tell what was going on in their lives and to speak openly about their behaviors and their environmental circumstances. Thirty percent of the middle schoolers said they were sad or had nothing to look forward to, and 24 percent of them reported carrying a weapon. Nearly half of the students had gotten into trouble because of anger, and 35 percent missed school for work, because of transportation issues, or because they had to care for someone in the family. One-third of the students were earning a grade of less than a C in one or more classes.

Among the high school students, 51 percent had had sex, and 25 percent of those were not using a condom or any type of protection. “It is not if they are going to get pregnant,” Wright said, “it is when are they going to get pregnant or cause a pregnancy.” More than one-third of the high schoolers carried a weapon to school, nearly one-third felt sad or hopeless, and 28 percent got in trouble because of anger. More than one-fifth of the students smoked marijuana or used other street drugs; 39 percent missed school for work, because of transportation issues, or to care for a family member; and about one-third had grades of less than a C in all of

their classes. “This is just a smattering of what you learn about what is going on in their lives when you give students a way to respond confidentially and without judgment,” Wright said.

In this assessment, Wright and her colleagues also asked about homelessness and whether the students had electricity or running water in their homes. “This is when you start unpacking what we mean when we talk about poverty and what it means in the lives of these young people: not being able to take a shower or wash their clothes and having to go to school perhaps not smelling good and being teased and then deciding they are not going back to school the next day because they are tired of being teased.” She said that this is why one principal asked a school-based health center to put a washer, dryer, and shower facilities in the health center.

Wright stressed the importance of gathering this type of information if the real goal is to make a significant and long-lasting impact in the lives of these young people. “I suggest to you that we are not going to change the indicators that we care about,” she said, “until we dig deeper, beyond the global bucket of poverty, to figure out what it is that is going on in their lives, get to the root of what is happening, and make a difference in their lives.” To conclude, she read some of the sobering stories that the students recounted:

- “[T]here was like 13 people in that house. . . . [A]fter a while, you know, there’s not enough food and everything for everybody to be there.”

- “One winter we had no heat. We had no electricity. We had no water. It was bad.”

- “People judge me for the way I look all the time. . . . I think it’s because I’m black and I’m tall. . . . I’m walking past cars, people lock their doors.”

- “What’s stressful in my life is being raped and getting pregnant from it.”

- “They took away the swings and the play skate [at the park]. . . . [T]here’s nothing but a basketball [court] there, and they don’t even have nets. . . . [I]t’s irritating and makes [me] mad.”

- “[B]ring all the rich people back . . . so they can fix it up. . . . I would put them in our place to see how it feels to be us at the bottom of the food chains.”

Raymond Baxter from Kaiser Permanente started the discussion by asking the panelists whether they believed that the fragmentation of systems will make it difficult to implement what he called “grand schemes” for aligning the health system with the education system. McGuire said that it will be a challenge to overcome the fragmentation of both the health and education systems but that it needs to happen, and he said

he thought that the biggest obstacle will be surmounting the language barrier that exists between the two fields. Wright said that to address this language issue her team engaged a consultant from the education community who could help translate education language into concepts that the health community could understand and who could help navigate the differences between these two communities. “You have got to learn the language,” she said. “You have got to learn the nuances. You have got to learn the protocols. You have got to learn the sweet spots that make sense for them, just like any other culture.”

Wright then commented on some of the expectations associated with the Affordable Care Act and the way that the health care community will need to identify and respond to social factors such as homelessness. “I am trained as a physician,” she said. “I am not trained as a fixer around that kind of social issue. I know that that social issue absolutely impacts what I see in an exam room, but I don’t know what to do about it.” One way to address this dilemma would be to integrate public health and primary care in a very deliberate and demonstrative way. This, Wright said, would give primary care providers some comfort in asking those questions because they will have other experts available to provide responses to those social factors.

George Isham from HealthPartners then asked what he characterized as a “provocative” question, which was how various organizations should determine their areas of focus, given the list of seven health care priorities that Charles Basch noted in his talk and other areas, such as oral health, that have been noted throughout the workshop. Solomon said that the questions that an organization has to ask itself as it figures out how to marshal its finite resources and connect to another organization are: “What do I have to offer? What are my unique competencies and expertise? What are my organizational imperatives? How can I build a case for connecting to another institution, another setting, another group of stakeholders in a way that I can actually bring something to the game that matters to my organization and my leadership?” Then, he said, once you get into a collaboration and start working on a few priority areas, others arise that can be identified and added to the list. “You can’t boil the ocean,” Solomon said. “You have to start somewhere, and you might as well start somewhere where you have got some competence and where schools have a willingness to engage.”

Debbie Chang explained that Nemours picked prevention as a focus area because there was a void that needed to be filled and the organization felt it had the capacity to work in that area. Then, in the course of understanding the connection between primary care and population health, the organization realized there was a need for work on asthma. Chang

summarized Nemours’ approach as being opportunistic, proactive, and prioritizing along the way.

Jeffrey Levi of Trust for America’s Health said that there are some collaborative grant programs, such as the school climate transformation program, that require potential grantees to apply for grants from each of the participating federal agencies. Other programs, such as the performance partnership grant initiative, blend funding from several agencies into one grant, an approach that required specific legislative authority. The relevance of this approach, Levi said, is that it helps break down the silos that were mentioned earlier in the workshop. McGuire wondered if the Roundtable could offer advice on how to modify grant programs and requests for proposals to encourage—rather than discourage—cross-sector collaboration. He also said that government agencies could be more effective if there were more strategic interaction among agencies at the stage at which programs are being designed. The research side could then weigh in on designs that will generate interesting results that could, in turn, create opportunities to learn how things work, McGuire said.

Michelle Larkin from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation asked the panel to comment on challenges and innovations in the area of dissemination and sustainability. Solomon replied that public resources are critical to sustaining efforts and that those resources can be marshaled, even in tough fiscal environments, when advocacy is brought to bear in order to raise awareness. Wright agreed with Larkin’s comment. Solomon said that without public resources, physical education will not be back in school and the spread of programs such as Colorado’s Breakfast After the Bell initiative will be limited.

Wright added that an important piece of sustainability is transformation. Transforming behavior—as opposed to merely throwing money at a problem—increases the odds that a successful program will find the support it needs to spread. For example, programs to address asthma in students that merely pass out inhalers are not transforming behavior, while those that include home teaching and that bring in a public health team to help address environmental and social factors that can make it difficult for a student to use their inhaler consistently are more likely to transform behavior. Taking the latter approach requires educating primary care physicians that writing a prescription for an inhaler or nebulizer is just the first step needed to treat their patients in a sustainable manner. The physicians need to start thinking about what else is going on in a student’s life and to know what other components of the health and school system need to be involved in that student’s care. Larkin added that the goal is to change the culture—to enable adults and children to be resilient and to empower them to create the change that needs to be fostered in their communities.

Sanne Magnan of the Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement brought up the need to find the right balance between accountability and flexibility—a need that health and education share. As an example, Magnan told the story of a fifth grader who did not receive a grade on spelling because her teacher did not want to give her a failing grade but instead wanted to address this student’s learning disability. The teacher may have gotten into trouble for her flexibility because she did not use consistent grading metrics. Similarly, she described the case of a man who was counseled to take a statin for elevated cholesterol but refused to do so—a response that was likely to cause that man’s physician to be scored lower on accountability measures even though the physician did counsel the patient to use a statin. The point of these stories, she said, is that there is a need to identify the right measures and accountability metrics in both health and education that can be used to advance a child’s welfare by considering the needs of specific patients and families. Solomon said that meeting this challenge is exactly what Trust for America’s Health and its partners in the Health in Mind campaign are doing. Commenting that the field is “drowning in metrics and indicators,” McGuire concluded the discussion session by saying, “We have to have the discipline to arrive at the smallest number of things that make the biggest difference in telling us if we are getting what we want.”

This page intentionally left blank.