4

The Shifting Career Landscape

Professional opportunities and career paths for scientists and engineers have changed dramatically over the past few decades. However, this shift has, for the most part, not been fully acknowledged within academe or the policy-making arena. Despite a growing body of evidence to the contrary, the dominant perception among mentors and funders is that the standard scientific career path goal remains a tenure-track faculty position at a research-intensive academic institution (references in Sauermann and Roach 2012). Compounding the issue, faculty advisors can be ignorant of—or biased against—what have been pejoratively termed “alternative” career paths and therefore are frequently incapable of advising their postdoctoral researcher on such options.

Efforts are being made by postdoctoral offices at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and many universities to reform graduate and postdoctoral training so that it is helpful to those who pursue career paths other than tenure-track academic research (Box 4-1). The National Postdoctoral Association maintains a database of university policies and practices, which includes career-related activities. In response to changes in the science and engineering labor market, more attention is being paid to career planning beginning earlier in the career trajectories of scientists and engineers. As mentioned in Chapter 3, the myIDP program and the numerous career-planning workshops conducted by individual universities are steps in the right direction, but universities need to provide more information about what their graduates do when they leave, and professional societies should provide more information about career trajectories in their disciplines. Universities should also be aware of the incongruity of making postdoctoral training more relevant for career paths that do not require or reward advanced research training, which suggests that transition to such career paths ideally must occur before the postdoctoral period commences. Therefore, the information required for trainees to make informed decisions about such careers must also be available before the commencement of postdoctoral training.

UNDERSTANDING THE CAREER DEVELOPMENT OPTIONS

Even with the promising developments of the past decade, many graduate students and postdoctoral researchers do not have sufficient information about possible career paths, job prospects, and earning potentials to make informed

Box 4-1

Career Exploration Opportunities

Many postdoctoral researchers acquired Ph.D.’s without acquiring much work experience outside of academic research. Two programs—the Graduate Student Internship for Career Exploration (GSICE) at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) and the National Institutes of Health’s National Institute of General Medical Sciences (NIGMS) biotechnology graduate research grants—address this issue by providing or requiring nonacademic experiences for graduates students.

The GSICE at UCSF recognizes that their Ph.D. recipients must be prepared for a variety of careers. The key aim is to include broader training in the UCSF graduate programs. This program, open to all graduate students in the basic and biomedical sciences, gives students work experience and provides career development workshops for 3 months (one academic quarter), and can be done either during or immediately following graduate school. Students can apply to be placed in companies in a variety of sectors, including education, business, and law. By encouraging students’ exploration of other career paths, UCSF is not only preparing their graduates for the likely diversity of careers they will end up in, but also encouraging their students to think more broadly about their work and where it could lead them.

The NIGMS awards fellowships to institutions training graduate students in various areas of biomedical research, in order to support graduate research and high-quality training for graduate students. Grants awarded in biotechnology require recipient institutions to “include a two- or three-month industrial internship [during graduate education], to give students a meaningful research experience in a biotechnology or pharmaceutical firm. This research experience may be fully integrated with the trainee’s Ph.D. research, but it may also be used by the trainee to delve into new areas.” The NIGMS programs are currently established at 20 institutions across the country, and demonstrate the leverage that funding agencies have to affect the experience of graduate students and postdoctoral researchers.

SOURCES: More information about GSICE is available at http://gsice.ucsf.edu/. Accessed May 8, 2014. More information about the NIGMS biotechnology program is available at http://www.nigms.nih.gov/Training/InstPredoc/pages/PredocDesc-Biotechnology.aspx. Accessed May 8, 2014.

decisions at the appropriate stages to select realistic career goals. In addition, the National Science Foundation (NSF), which collects data on scientists and engineers, does not collect any data on the career outcomes of postdoctoral researchers who earned their doctorates in another country. Because a large fraction of today’s postdoctoral researchers received their doctorates outside the United States, essential information simply is not yet collected.

Tracking Postdoctoral Researchers

Even for those who earned their Ph.D.’s in the United States, data about employment are quite limited. The economist Paul Romer conducted a revealing study in the late 1990s in which he asked a research assistant to request information about graduate study at 10 leading departments of biology, physics, chemistry, mathematics, computer science, and electrical engineering, and at 10 leading law and business schools (Romer 2001). None of the science and engineering departments provided information about the salaries of their graduates, nor did they provide information when it was specifically requested again in a later inquiry. Seven of the 10 business schools and four of the 10 law schools included salary information in the application packet. One more business school and three more law schools provided information in response to a later request.

The situation has apparently improved very little in the following decade. A 2008 survey of the websites of 15 top graduate programs in electrical engineering, chemistry, and biomedical sciences produced disappointing results. Of the 45 programs surveyed about placement of their graduates, only 2 had specific information, and 4 had some general information. By contrast, visits to 15 top economics department websites showed that 7 provided annual lists of where students found jobs. In addition, it should be noted that the collected information was for applicants to graduate school and not for postdoctoral researchers. In general, there is a stronger institutional interest in graduate students than in postdoctoral researchers; information about placement of postdoctoral researchers is virtually nonexistent (Stephan 2012).

There are some programs that attempt to follow the career trajectories of postdoctoral researchers, but the populations that have been studied are still very small and the data are difficult to find (Box 4-2).

Box 4-2

Postdoctoral Researcher Exit Surveys

Several institutions have implemented an exit survey, either through a postdoctoral office or postdoctoral association. These surveys provide institutions with an opportunity to gather valuable feedback from postdoctoral trainees that can be used to develop new policies and training programs, evaluate satisfaction with existing policies and programs, identify problems and areas for improvement, enable data-driven policy decisions, and track the career pathways of departing postdoctoral researchers. These surveys also provide an opportunity for postdoctoral researchers to give constructive feedback to their institutions, and are used by the institutions to establish a database of postdoctoral researchers and an alumni community.

Although implementation of exit surveys varies widely, there are common characteristics. Surveys are often provided online, and results are typically reported anonymously before being used to inform institutional policies. Survey questions tend to fall into three categories: personal and demographic information, details of the postdoctoral experience, and information on future plans. In addition to tracking the career pathways of departing trainees, the questions about the postdoctoral experience afford the postdoctoral researcher an opportunity to rank the performance of the institution and offer other feedback that may contribute to the improvement of existing programs.

Examples of institutional exit surveys

- Brown University – http://www.brown.edu/about/administration/biomed/graduatepostdoctoral-studies/end-appointment-process

- Indiana University School of Medicine - http://www.surveymonkey.com/s.aspx?sm=Mxfp3s_2f7Bx0EukMOuwlvtQ_3d_3d

- Medical College of Wisconsin (Password protected) – http://www.mcw.edu/postdoc/exitsurvey.htm

- The Scripps Research Institute - https://www.surveymonkey.com/s/pdexitsurvey_v4

- Stanford University (Password protected) - http://unmc.edu/postdoced/exitsurvey.htm

- University of Kansas Medical Center - https://survey.kumc.edu/se.ashx?s=5A1E27D26557444B

- University of Chicago Biological Sciences Division - https://www.research.net/s/Postdoc_Exit_Survey-Contact_and_Job_Info

- University of Nebraska Medical Center - http://unmc.edu/postdoced/exitsurvey.htm

- University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill - https://apps.research.unc.edu//exit_survey/survey.cfm

- University of Tennessee Health Science Center - http://www.uthsc.edu/postdoc/pdfs/Postdoc-Exit-Survey.pdf

- Washington University in St. Louis Division of Biology and Biomedical Sciences - http://dbbs.wustl.edu/Postdocs/Postdoc%20Alumni/Pages/PostdocAlumni.aspx

- Yale University (Password protected) - http://postdocs.yale.edu/postdocs/leavingyale

SOURCES: National Research Council. “Enhancing the Postdoctoral Experience for Scientists and Engineers: A Guide for Postdoctoral Scholars, Advisers, Institutions, Funding Organizations, and Disciplinary Societies.” Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2000. More information http://www.nationalpostdoc.org/recommendations. Accessed May 8, 2014. Exit Survey examples last accessed April 17, 2014.

Attractiveness of the Academic Career Pathway

Assertions by policy makers about the career trajectories of postdoctoral researchers stem from calculations based on limited data. The data that do exist provide an overall picture of the career outlook for postdoctoral researchers and some detailed information about particular disciplines. For example, the NIH Biomedical Research Workforce Working Group compiled a flow chart for the career trajectories of U.S.-trained biomedical Ph.D.’s for their 2012 report; it indicated that more than 65 percent enter postdoctoral positions (BMW 2012).25 With caveats about the quality of the data, the NIH advisory committee estimated that about 23 percent of biomedical Ph.D.’s move into tenure-track faculty positions (seeTable 4-1 for a complete breakdown).

Survey research by Sauermann and Roach found that postdoctoral researchers do have a relatively accurate impression of the percentage of Ph.D.’s who find tenure-track research faculty positions within five years (seeTable 4-2, Sauermann and Roach 2013), but this apparently does not discourage a large percentage of graduates from pursuing postdoctoral training for that purpose.26 Sauermann speculates that, because they have always been at the top of the class and work at top-tier institutions, postdoctoral researchers assume that they also will be the lucky ones who obtain their desired jobs. Such findings highlight the fact that before becoming postdoctoral researchers, graduate students need more disaggregated information to truly understand the labor market. They especially need to know the outcomes for postdoctoral researchers at specific institutions.

As was highlighted in the BMW Report, a significant number of graduates pursue other types of research careers, including many that are open to people without postdoctoral experience. Nearly one-third enter positions that do not use

TABLE 4-1 Career outcomes for biomedical Ph.D. recipients

| Position | Percentage | |

| Tenure-Track Faculty Positions | 23 | |

| Non-Tenured Academic Research or Teaching | 20 | |

| Industrial Research | 18 | |

| Government Research | 6 | |

| Science-Related Positions (Non-Research) | 18 | |

| Non-Science-Related Positions | 13 | |

| Unemployed | 2 | |

SOURCE: BMW 2012

_____________________________

25 During the writing of the Biomedical Workforce Report, the rate at which U.S.-trained doctorates with definite commitments entered into postdoctoral positions for the life sciences was closer to 70 percent.

26 The Sauermann and Roach survey was conducted via on-line web survey at 39 tier-one U.S. research universities with doctoral programs in science and engineering fields determined by consulting the National Science Foundation’s reports on earned doctorates (Materials and Methods section of Sauermann and Roach 2012).

TABLE 4-2 Results of the Sauermann and Roach Postdoctoral Researcher Survey (percent)

| Life Sciences | Chemistry | Physics | Engineering | |

|

Ph.D.’s holding a tenure-track faculty position 5 years after graduation |

||||

|

• S&E* Indicators, 2012 |

14.3 | 16.5 | 16.5 | 15.5 |

|

• Postdoc’ Estimate |

14.7 | 15.5 | 13.3 | 17.1 |

|

Pursued a postdoc primarily to obtain a tenure-track faculty position in the future |

61 | 55 | 63 | 47 |

|

• If yes, probability that they will hold a tenure-track faculty position in 5 years |

55 | 68 | 42 | 58 |

|

Desired position for Ph.D.’s |

||||

|

• Faculty-Teaching |

23 | 20 | 22 | 9 |

|

• Faculty-Research |

30 | 14 | 29 | 25 |

|

• Government |

10 | 13 | 14 | 14 |

|

• Established Firm |

18 | 34 | 17 | 29 |

|

• Start-up Firm |

9 | 10 | 13 | 19 |

|

• Other |

10 | 9 | 5 | 5 |

|

Desired position for Postdocs |

||||

|

• Faculty-Teaching |

18 | 15 | 15 | 9 |

|

• Faculty-Research |

44 | 41 | 50 | 44 |

|

• Government |

14 | 19 | 19 | 18 |

|

• Established Firm |

13 | 15 | 6 | 21 |

|

• Start-up Firm |

5 | 7 | 5 | 7 |

|

• Other |

6 | 3 | 5 | 2 |

*S&E: Science and Engineering

SOURCES: Sauermann and Roach 2013, and unpublished presentation by Sauremann to the Committee on Science Engineering and Public Policy on September 9, 2013, available at

http://sites.nationalacademies.org/PGA/cs/groups/pgasite/documents/webpage/pga_084875.pdf, accessed on July 24, 2014.

their research skills (BMW 2012, Kahn 2011). Moreover, the data used to determine this level of skill mismatch are now “dated” and reflect the period when the NIH budget was doubling. In the flat funding environment of today, these data likely overstate the possibility of attaining a research position. Although independent postdoctoral research training could conceivably have

some value for someone in a non-research career, in many, if not most cases, the time spent in a postdoctoral position might have been more productively spent acquiring experience directly relevant to that career (BMW 2012).

Although the federal government has assumed most of the responsibility for collecting data about postdoctoral researchers, the institutions where they work are actually in the best position to track what postdoctoral researchers do after completing their training. The current effort to match the UMETRICS data for graduate students and postdoctoral trainees supported on federal grants at 12 universities to U.S. Census data is one promising experiment (Weinberg 2014). Collecting and making available information on the subsequent career paths of postdoctoral researchers would be very helpful to Ph.D.’s deciding whether to pursue postdoctoral training or not and to the nation’s research agencies, which must decide if their investment in postdoctoral training is producing the desired results (see Box 4-3).

Box 4-3

The United Kingdom’s Concordat to Support the Career Development of Researchers

A common complaint among postdoctoral researchers is the ambiguity of the position. Expectations and experiences vary among institutions and among principal investigators, making it difficult to determine if one is receiving proper treatment and management. In an effort to clarify what postdoctoral training should entail, a coalition of institutions in the United Kingdom, managed by Research Councils UK, developed the Concordat to Support the Career Development of Researchers, which has been endorsed by funding agencies, prominent scientific institutions, major universities, and professional societies.

The Concordat establishes important principles and sets explicit standards for the roles of principal investigators, mentors, supervisors, and the postdoctoral researchers themselves. The Concordat sets out seven key principles for funders and employers, including recognition of researchers’ role in their host institution and the importance of personal and career development. The principles include a system of oversight, with one principle being that “[t]he sector and all stakeholders will undertake regular and collective review of their progress in strengthening the attractiveness and sustainability of research careers in the UK.” For example, under the Concordat, regular surveys are done to track whether scientists are given the opportunity (and take the opportunity) to participate in management training. Additionally, many awards take into consideration institutional compliance with the principles in the Concordat.

SOURCE: Vitae. “Concordat to Support the Career Development of Researchers: An Agreement between the Funders and Employers of Researchers in the UK” https://www.vitae.ac.uk/policy/vitae-concordat-vitae-2011.pdf. Last accessed May 8, 2014

POSTDOCTORAL RESEARCHERS SUPPLY AND USE

Policy recommendations from the research community repeatedly warn of imminent shortages of graduates in science and engineering,27 but some job market data do not indicate a shortage. In many fields, more doctoral recipients are being produced in the United States and abroad than the market for research positions demands, given current levels of funding. (Stephan 2012). In addition, most of these studies focus on undergraduate, masters, and professional degree programs, not postdoctoral researchers.

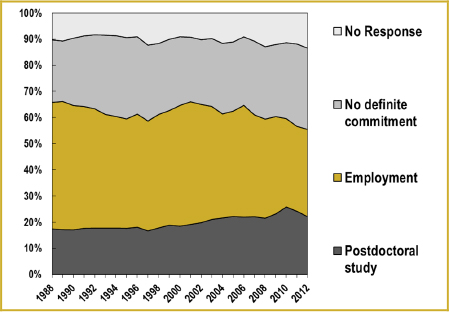

The supply of domestic doctorates depends on the number of Ph.D.’s who have recently been produced, and the options they have for other types of employment. In recent years, the supply, especially in engineering and the biomedical sciences, has been growing, while job opportunities outside of academia have not matched this increase. As a result, fewer new Ph.D.’s have definite commitments at the time they graduate, and those who do have plans are more likely to take a postdoctoral position (Figure 4-1).

FIGURE 4-1 Postgraduation plans of U.S.-trained doctorate recipients.

SOURCE: Data compiled from the NSF, NIH, U.S. Department of Education, U.S. Department of Agriculture, National Endowment for the Humanities, and NASA Survey of Earned Doctorates: 2012, 2011, 2010, 2009, and 2008.

_____________________________

27 For example PCAST 2012a.

In addition, the number of postdoctoral researchers per faculty position has more than doubled since the early 1970s.28 Each year, U.S. universities produce almost 28,000 new Ph.D.’s in science and engineering alone (GSS data). Moreover, a growing number of foreign-trained doctorates, notably from emerging economies such as China and India, add to supply. These trends have shown a dramatic increase in the past decade, especially in engineering and the biomedical sciences.29 At the same time, the percentage of doctoral recipients obtaining tenure-track faculty positions has been declining, and this trend does not show any sign of reversal (Table 4-3). Therefore, it would appear that far more doctoral recipients are pursuing postdoctoral training than there are job openings that require such training.

In other words, for many the postdoctoral researcher position is becoming the default after the attainment of the Ph.D., especially in the life sciences, and the decision to seek a postdoctoral position is often made without regard to whether advanced training in research is really warranted for the individual in question.

A major point of discussion is the historically low salary paid to postdoctoral researchers. The demand for workers with certain types of training and the salaries offered for different types of expertise are affected by a number of factors such as the business cycle, government research funding, industrial research and development budgets, and immigration policy. As with actual markets, the lower the salary, the greater the demand will be from principal investigators to hire postdoctoral researchers if it is perceived that doing so provides greater research output than hiring either staff scientists or additional graduate students.30 The research enterprise does not have a fixed need for a certain number of postdoctoral researchers; instead, principal investigators will typically hire a larger number of Ph.D.-trained workers when their funding allows.

_____________________________

28 According to the NSF-NCSES special tabulations (2013) of the 1973–2010 Survey of Doctorate Recipients, the ratio of U.S. trained postdoctoral researchers to full-time faculty increased nearly 170 percent from 1973. In addition, according to the GSS, between 2000 and 2010, the number of postdoctoral researchers increased from 43,115 to 63,415, or a 47 percent increase and the number of graduate students increased from 493,311 to 626,820, or a 28 percent increase. Over that same time period, the Department of Education’s Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System (IPEDS) Salaries, Tenure, and Fringe Benefits Survey for Faculty reported only a 13 percent increase in tenure and tenure track faculty positions (from 369,784 to 421,370), and a 21 percent increase in the total faculty (from 490,861 to 604,393), but a 45 percent increase in “Instructors, Lecturers, and Other” (non-tenure/tenure-track) faculty positions (from 121,077 to 183,023). The ratio of postdoctoral researchers to tenure and tenure-track faculty, according to GSS/IPEDS data, increased nearly 150 percent since 1975.

29 More details on these trends may be found in Chapter 2.

30 Discussed further below.

TABLE 4-3 Employed U.S.-trained science, engineering, and Health (SEH) doctorate recipients holding tenure and tenure-track appointments at academic institutions, by field of and years since degree: 1993–2010 (Percent)

| Years since doctorate and field | 1993 | 1995 | 1997 | 1999 | 2001 | 2003 | 2006 | 2008 | 2010 |

| < 3 years | |||||||||

|

All SEH fields |

18.1 | 16.3 | 15.8 | 13.5 | 16.5 | 18.6 | 17.7 | 16.2 | 14.7 |

|

Life sciences a |

9.0 | 8.5 | 9.3 | 7.7 | 8.6 | 7.8 | 7.2 | 6.5 | 7.6 |

|

Computer/information sciences |

31.5 | 36.5 | 23.4 | 18.2 | 20.7 | 32.5 | 31.2 | 22.0 | 20.8 |

|

Mathematics and statistics |

40.9 | 39.8 | 26.9 | 18.9 | 25.2 | 38.4 | 31.6 | 31.3 | 26.1 |

|

Physical sciences |

8.8 | 6.9 | 8.5 | 7.8 | 10.0 | 13.3 | 9.8 | 8.8 | 6.8 |

|

Psychology |

12.8 | 13.6 | 14.7 | 16.0 | 15.6 | 14.6 | 17.0 | 18.1 | 16.0 |

|

Social sciences |

43.5 | 35.9 | 37.4 | 35.4 | 38.5 | 44.8 | 39.3 | 45.4 | 41.1 |

|

Engineering |

15.0 | 11.5 | 9.4 | 6.4 | 11.3 | 10.8 | 12.4 | 9.3 | 7.5 |

|

Health |

33.9 | 34.2 | 30.1 | 28.1 | 32.1 | 30.3 | 36.2 | 27.7 | 24.2 |

|

3–5 years |

|||||||||

|

All SEH fields |

27.0 | 24.6 | 24.2 | 21.0 | 18.5 | 23.8 | 25.9 | 22.9 | 19.7 |

|

Life sciences a |

17.3 | 17.0 | 18.1 | 16.4 | 14.3 | 15.5 | 13.7 | 14.3 | 10.6 |

|

Computer/information sciences |

55.7 | 37.4 | 40.7 | 25.9 | 17.3 | 32.2 | 45.7 | 37.8 | 22.2 |

|

Mathematics and statistics |

54.9 | 45.5 | 48.1 | 41.0 | 28.9 | 45.5 | 50.6 | 40.7 | 41.7 |

|

Physical sciences |

18.8 | 15.5 | 14.5 | 11.9 | 15.8 | 18.3 | 19.7 | 16.5 | 14.7 |

|

Psychology |

17.0 | 20.7 | 16.8 | 17.6 | 17.5 | 19.9 | 23.8 | 18.3 | 19.1 |

|

Social sciences |

54.3 | 52.4 | 50.4 | 46.5 | 38.8 | 46.0 | 50.4 | 48.9 | 46.7 |

|

Engineering |

22.7 | 19.3 | 19.4 | 12.6 | 10.8 | 15.9 | 16.3 | 15.5 | 13.0 |

|

Health |

47.4 | 40.2 | 41.1 | 39.5 | 25.1 | 40.8 | 43.1 | 34.4 | 33.3 |

a Includes Biological, agricultural, and environmental life sciences.

NOTES: Proportions are calculated on the basis of all doctorates working in all sectors of the economy. Data for 1993–99, 2001, and 2006 include graduates from 12 months to 60 months prior to the survey reference date; data for 2003, 2008, and 2010 include graduates from 15 months to 60 months prior to the survey reference date.

SOURCE: National Science Foundation, National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics, Survey of Doctorate Recipients (1993–2010), http://sestat.nsf.gov. Science and Engineering Indicators 2014

Current Salary Levels

As described in Chapter 2, biomedical postdoctoral researchers are the largest segment of the postdoctoral population. As a result, NIH policies tend to

set the tone for all postdoctoral positions in terms of salary, benefits, and duration.31 In many institutions, and especially in the biomedical sciences, the NIH National Research Service Award (NRSA) postdoctoral salary rate becomes “the” salary that all postdoctoral researchers are paid.

The NIH NRSA stipend for beginning postdoctoral researchers in 2004 was $35,568, which would be $43,230 in 2012 dollars (or $44,207 in 2014 dollars). Despite repeated calls to raise postdoctoral salaries, the NRSA stipend was increased to only $39,264 in 2012. In 2014, NIH raised the stipend to $42,000, which, in real terms, is actually lower than the 2004 level. Institutions that do match the NRSA minimum tend to lag by 6 to 8 months, and many have yet to implement this most recent increase. Whereas some institutions do not match the NRSA stipend level, others pay considerably more. An extraordinary example is that of the postdoctoral researcher salary rates at the Los Alamos National Laboratory, where beginning postdoctoral researchers received a salary of $72,200 in 2013.32 These institutions, however, also often use the postdoctoral position as a way of screening future employees, something that is rarely done in academe.

Principal investigators, and some funding agencies, have recognized the financial advantages of hiring postdoctoral researchers rather than graduate students or staff scientists to work on research grants. Graduate student stipends coupled with tuition charges are often on par with—or exceed—standard postdoctoral researcher salaries, especially at private universities.33 Postdoctoral researchers also come with more experience than graduate students, do not require the same level of supervision and training, and according to the 2006 Survey of Doctorate Recipients, work between 2,500 and 2,650 hours a year depending on field (Stephan 2012), compared to just over 2100 hours a year for the average full-time worker the United States.34 Staff scientists have research expertise comparable to postdoctoral researchers, but standard salaries and

_____________________________

31 The NPA survey from late fall of 2011 found that at 47 percent of the responding institutions “the minimum salary or stipend was the NIH National Research Service Award (NRSA) stipend for 0 years of experience or gave the equivalent amount of $38,496. Other responses (41 percent) reported dollar amounts ranging from $28,000 to $55,000…, with most responses in the $35,000–$38,000 range.” More information can be found at http://www.nationalpostdoc.org/images/stories/Documents/Other/npa-survey-report-april-2012.pdf, last accessed April 4, 2014.

32 More information can be found at http://www.lanl.gov/careers/career-options/postdoctoralresearch/postdoc-program/postdoc-salary-guidelines.php, last accessed April 9, 2014.

33 Compiling data from GradPay—a crowdsourcing website set up to collect information about graduate student stipends—and IPEDS Institutional Characteristics Survey Tuition Data, it was determined that the average total cost for a science, engineering, or health graduate student in 2011 was approximately $50.7 thousand, ranging from around $40 thousand to an extreme of $94 thousand. Data were gathered for 73 institutions and 51 self-identified science, engineering, or health fields. More information about GradPay is available at http://gradpay.herokuapp.com/, last accessed April 8, 2014.

34 More information can be found at http://www.bls.gov/cps/cpsaat19.pdf, last accessed September 9, 2014.

benefits for these positions can be twice as high as a typical postdoctoral stipend. Clearly, postdoctoral researchers can be a bargain compared with many graduate students and staff scientists, from the perspective of a principal investigator. In fact, postdoctoral salaries, which start on average at about $41,000 a year, are approximately 52 percent of the average nine-month salary for newly hired assistant professors at public research universities (OSU 2014) and have not kept pace with other positions, making postdoctoral researchers an even more financially appealing choice.35

The starting salary is also low compared with other employment sectors. New Ph.D.’s who do not take postdoctoral positions at universities, for example, can command a starting salary that is 40 to 200 percent more than their counterparts, depending on their field and sector of employment (Survey of Earned Doctorates data). The postdoctoral starting salary is low even relative to that of those who earned only a bachelor’s degree who, by the time they reach their late 20’s to early 30’s, were earning about $49,911 in 2012.36 If one assumes that this is actually a market economy, the question arises as to why postdoctoral salaries are so low. One part of the answer is that the presence of temporary residents in the labor market, coupled with the large supply created by Ph.D. programs in the United States and the lack of alternative types of positions, puts downward pressure on postdoctoral wages and makes it possible for principal investigators to fill their laboratories with newly minted Ph.D.’s at “rock-bottom prices.” 37 Further, the number of postdoctoral researchers is largely set by the availability of research support (typically federal), rather than by the availability of suitable research positions after the postdoctoral period. Thus the scientific labor market for postdoctoral researchers does not function like a labor market in the usual economic sense of the term.

The Value of Training

The traditional rationale put forward to justify the low salaries paid to postdoctoral researchers is that advanced training positions will qualify the postdoctoral researcher for a better-paying position in the future. However, this argument can be challenged on several fronts.

First, there is no guarantee that the postdoctoral researcher will receive significant experience to prepare her or him for full-time independent research

_____________________________

35 The average nine-month salary of a newly hired assistant professor at public research universities in the biological and biomedical sciences is $74,177; in engineering it is $84,012; in math and statistics it is $67,383 (OSU 2014).

36 U.S. Census Bureau, Current Population Survey, Annual Social and Economic Supplements. Table P-28. “Educational Attainment—Workers 18 Years Old and Over by Mean Earnings, Age, and Sex: 1991 to 2012” More information can be found at http://www.census.gov/hhes/www/income/data/historical/people/, last accessed June 9, 2014.

37 For many non-U.S. doctorates, a $41,000 salary and the possibility of ultimately becoming a U.S. citizen is a very appealing option. Thus, it is not surprising that a majority of U.S. postdocs are on temporary visas, and a majority of these postdocs earned their Ph.D.’s in other countries.

positions. Roughly 80 percent of postdoctoral researchers are employed by principal investigators and paid out of research grants. The principal investigators are currently under no obligation to provide opportunities for development, such as experience writing grants, managing a laboratory, or giving presentations. This means that, in many cases, any training that occurs is a byproduct of work, rather than planned career development activity.

Second, as the discussion above indicates, the number of job openings each year that require postdoctoral training is far lower than the number of people who acquire postdoctoral positions each year. Although no one can be promised a job just because he or she completes a postdoctoral appointment, those entering a training program should know how well their predecessors fared in the job market.

Third, to the extent that training occurs, postdoctoral researchers pay an extremely high price for it. As mentioned, postdoctoral researchers work approximately one-third more hours than the average full-time worker in the United States,38 yet earn on average about 20 percent less than people of a comparable age who have only a bachelor’s degree. That works out to approximately 40 percent less per hour.

Fourth, when postdoctoral researchers do eventually pursue nonacademic or non-research jobs, they do not receive a wage premium for their additional training. Overall, the sacrifices made by postdoctoral researchers in salary and benefits are not compensated later in their careers. On average, postdoctoral researchers start at lower salaries than what is paid to graduates who entered similar jobs immediately after earning their Ph.D., even though a postdoctoral researcher has had several years of additional research experience (Kahn 2011). Additionally, the total earnings of postdoctoral researchers trail those of their Ph.D.-only contemporaries for the rest of their careers (Kahn 2011). Employers appear to be sending a signal that the time spent in postdoctoral research is not valued in many job markets.

Doctorate recipients are adults who have the right to choose a career path and accept low wages if they think that it will eventually lead to a satisfying career. However, there is a difference between abstract knowledge and concrete understanding of the prospects of those individuals who attend the same institution they are considering. To make informed decisions, they need detailed information on the current job market and the job results for those who have completed postdoctoral training broken down by field and institution. Too few institutions are collecting and disseminating those data.

_____________________________

38 More information can be found at http://www.bls.gov/cps/cpsaat19.pdf. Last accessed September 9, 2014.

This page intentionally left blank.