In addition to the renal toxicity and neurobehavioral effects discussed in the preceding chapters, the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) will pay for the treatment of 13 other medical conditions specified in the Janey Ensminger Act. These conditions are detailed in the VA guidance and accompanying algorithms to help clinicians and administrators make decisions about whether or not veterans and family members are eligible for health care benefits under the Camp Lejeune Program. These other outcomes are presented here in the same order as in the guidance: cancer, scleroderma, miscarriage and infertility, and hepatic steatosis. The description and discussion of each outcome includes a brief overview, a review of the documentation and algorithm, and the committee’s recommendations for improvement. Where applicable, algorithms have been revised to highlight the committee’s suggested changes. Discussion of VA’s decision-making process for the health conditions listed in the act, including screening and secondary health conditions, is presented in Chapter 5.

CANCER AND RELATED CONDITIONS

Overview

The Janey Ensminger Act lists eight malignant neoplasms (esophageal cancer, lung cancer, breast cancer, bladder cancer, kidney cancer, leukemia, multiple myeloma, and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma) and myelodysplastic syndromes among the 15 conditions covered by the act. These conditions were included in the legislation because of evidence presented in the 2009 National Research Council (NRC) report, which concluded that there was “limited/suggestive evidence of an association” between chronic exposure to solvents, particularly perchloroethylene (PCE), and cancers of the breast, bladder, kidneys, esophagus, and lungs (NRC, 2009). The toxicologic evidence was strongest for the associations between trichloroethylene (TCE) and kidney cancer and between PCE and kidney cancer. The report found that there was limited/suggestive evidence of an association between solvent mixtures and adult leukemia, myelodysplastic syndromes, and multiple myeloma. The report also concluded that there was inadequate/insufficient evidence to determine whether an association exists between non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma and TCE, PCE, or solvent exposure.

New Research

Reports and meta-analyses published since the 2009 NRC report have also assessed whether exposure to TCE or PCE results in an increased risk of cancer, including dying from a cancer (Christensen et al., 2013; Hansen et al., 2013; Lipworth et al., 2011; Scott and Jinot, 2011). These new studies have generally supported the conclusions of the previous report and also addressed other cancers.

Because a number of authoritative reviews of the carcinogenicity of various solvents have been published since the NRC report in 2009, the committee summarizes the conclusions of those reviews in the following sections. These documents were written or reviewed by panels of experts, and the information in them was collected, analyzed, and presented systematically. The committee also reviewed two studies conducted by Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR) of military and civilian cohorts exposed to contaminated water at Camp Lejeune (Bove et al., 2014a,b).

Authoritative Reviews

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) published toxicologic reviews of TCE and PCE in 2011 and 2012, respectively. Based on human studies, EPA found that TCE is carcinogenic by all routes of exposure (ingestion, inhalation, etc.) with clear evidence of a causal relationship between TCE and kidney cancer in humans. Evidence was strong for an association between TCE and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma but less so for liver and biliary cancer, esophageal, prostate, cervical, breast, and childhood cancers (EPA, 2011). EPA also concluded that PCE is likely to cause cancer in humans by all routes of exposure. This conclusion is supported by suggestive evidence in humans and by conclusive evidence in animals. Epidemiologic studies show associations between PCE and bladder cancer, non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, and multiple myeloma. More limited data exist for esophageal, kidney, lung, cervical, and breast cancers (EPA, 2012).

In 2013, the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) published assessments of the association of TCE and PCE with cancer. Human studies were used to determine what specific kinds of cancer each solvent caused. Regarding TCE, IARC found sufficient evidence in humans and animals to conclude that it causes cancer. IARC found that there is sufficient evidence that TCE causes kidney cancer and identified a positive association between TCE and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma and liver cancer. It also reported statistically significant excess risks of lung, cervix, and esophageal cancers, but the evidence was insufficient to allow for specific associations to be made. Regarding PCE, IARC concluded from sufficient evidence in animals and limited evidence in humans that it is probably carcinogenic in humans. Human data show a positive association between PCE and bladder cancer, but the evidence was inconsistent for non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, and esophageal, kidney, and cervical cancers (IARC, 2014a,b).

ATSDR Studies

ATSDR has published three epidemiologic studies investigating cancers in the Camp Lejeune population exposed to contaminated drinking water. Ruckart et al. (2013) looked at increased risks of cancer among 12,598 children born to mothers residing at Camp Lejeune. The study reported eleven cases of leukemia and two cases of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma in children exposed while in utero. The odds ratios (ORs) for any childhood cancer were elevated but not statistically significant for first-trimester exposure to PCE, vinyl chloride, and dichloroethylene. This study was limited by the small numbers of events and the possibility of differential recall bias and missing data. Bove et al. (2014a) compared the mortality of Marine Corps and Navy personnel exposed to contaminated drinking water at Camp Lejeune with that of Marine Corps and Navy personnel stationed at Camp Pendleton. Elevated hazard ratios for the Camp Lejeune cohort were reported for deaths resulting from kidney cancer, liver cancer, esophageal cancer, cervical cancer, multiple myeloma, and Hodgkin lymphoma; however, the confidence intervals all included 1.0 (Bove et al., 2014a). The same authors conducted an almost identical analysis among civilian workers employed at Camp Lejeune and Camp Pendleton. Elevated but statistically nonsignificant hazard ratios for the Camp Lejeune cohort for kidney cancer, hematopoietic cancers, multiple myeloma, leukemias, rectal

cancer, lung cancer, and oral cancer were observed among the 197 total deaths at Camp Lejeune and 234 at Camp Pendleton (Bove et al., 2014b). The authors concluded that a longer follow up would be necessary in both cohorts to allow for more precise estimates because only 6% of the military cohort and 14% of the civilian cohort had died at the time of the assessment (Bove et al., 2014a,b).

Latency

Adult cancers have latency periods of years and childhood cancers have latency periods of at least months (de Gonzalez et al., 2012). The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s World Trade Center Health Program has summarized the latency periods for various cancers, suggesting a minimum latency of 4 to 20 years for most solid tumors and several months to 10 or 15 years for lymphoproliferative and hematopoietic cancers (Howard, 2013). The VA guidance and algorithm do not explicitly consider latency in coverage determinations for the cancer diagnoses.

VA Guidance and Core Algorithm

For the eight cancers and myelodysplastic syndromes covered by the act, there are well-established diagnostic criteria. The Camp Lejeune program includes additional health care benefits in the form of comprehensive medical care during active cancer treatment, because such treatment (including surgery, chemotherapy, and radiation) can result in systemic secondary effects on virtually all other organ systems. The treating oncologist may specify the active treatment time period or VA will provide coverage in 6-month increments after the initial diagnosis.

The core algorithm in the guidance is used for all the cancers regardless of other risk factors and time of onset. (Onset, latency periods, and exposures for cancer are only briefly mentioned in the guidance on page 7.) Because the diagnosis of these cancers is expected to be based on established criteria and because the risk attributable to other causes cannot be ascertained, all qualified veterans and family members with one of these diagnoses are automatically accepted to the Camp Lejeune program and are eligible for coverage (Walters, 2014a).

Recommendations

The core clinical algorithm addresses cancer diagnoses, asking whether the veteran or family member has an established diagnosis of one of the eight cancers or myelodysplastic syndromes. Although this is relatively straightforward, VA may want to consider the following findings and recommendations:

- According to VA, it plans to cover tumors regardless of latency. This follows the precedent set by VA in response to Agent Orange exposures for Vietnam veterans, and provides the benefit of the doubt to the veteran and, in this case, the family member (Walters, 2014a).

The committee recommends that VA clearly state in the guidance its policy decision to not consider the latency of cancers.

- Second, VA may want to clarify whether it will cover second primary cancers if the first primary (which must be one of the cancers covered by the act) occurred before the exposure at Camp Lejeune.

The committee recommends that VA include in the Camp Lejeune program patients with second primary cancers (but not recurrent or metastatic cancers) whose primary cancer was one of the covered cancers, even if their first primary cancer was diagnosed before residence at Camp Lejeune.

- Third, the guidance and algorithm do not address whether precancerous lesions of the cancers covered by the act are also covered—such as ductal carcinoma in situ (noninvasive breast cancer); Barrett’s esophagus, which can precede esophageal cancer; and monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance, which

may precede multiple myeloma. VA has indicated to the committee that it plans to cover precancerous lesions (Walters, 2014b), and the committee finds this approach to be reasonable.

The committee recommends that VA clearly address precancerous lesions in the clinical guidance and in the core algorithm.

- Fourth, the guidance defines active treatment for cancer as surgery, chemotherapy, or radiation therapy, or some combination of the three, but it does not specifically include hormonal treatment or immunotherapy. Even if the primary purpose of such treatment is to prevent the recurrence of cancer (e.g., hormonal therapy to prevent recurrence of breast cancer), such treatment is indicated in 38 CFR 17.38, which states that the VA medical benefits package covers treatment to prevent recurrence of a disease.

The committee recommends that VA specifically include hormonal treatment and immunotherapy as part of the “active treatment” for cancer in the clinical guidance.

SCLERODERMA (SYSTEMIC SCLEROSIS)

Overview

Scleroderma, also referred to as systemic sclerosis, is a rare autoimmune condition characterized by the presence of thickened, sclerotic skin lesions. It is the result of an overproduction and accumulation of collagen in tissues (Scleroderma Foundation, 2014). The impact and symptoms vary from having patches of hardened skin to the involvement of other tissues and organs such as the heart, lungs, kidney, and digestive system (Scleroderma Foundation, 2014). Scleroderma is thought to be caused by several factors, with the immune system, vascular system, and connective tissue metabolism all playing a role (NORD, 2014). Scleroderma occurs most commonly in adults (Scleroderma Foundation, 2014).

Scleroderma can be broadly classified into three groups: systemic sclerosis or systemic scleroderma; localized scleroderma1 (morphea and linear scleroderma); and scleroderma-like conditions, a heterogeneous group of diseases linked by the presence of thickened, sclerotic skin. These scleroderma-like conditions include eosinophilic fasciitis, localized forms of scleroderma, scleredema and scleromyxedema, keloids, and environmental exposure–associated conditions, including eosinophilia–myalgia syndrome and pseudosclerodermas induced by various drugs (Mori et al., 2002). CREST syndrome (calcinosis, Raynaud’s phenomenon, esophageal dysfunction, sclerodactyly, and telangiectasia) is another subdisorder (ISN, 2014). Risk factors for scleroderma include abnormal immune activity, environmental triggers, and genetic predisposition (NORD, 2014).

Scleroderma has an annual incidence of 1 to 2 per 100,000 individuals in the United States (Lawrence et al., 1998). Estimates indicate that scleroderma affects between 40,000 and 165,000 people in the United States (NORD, 2014). Peak onset is between the ages of 20 and 55, and the disease is more common in women (Mayo Clinic, 2013; NORD, 2014; Scleroderma Foundation, 2014).

The diagnosis of scleroderma can be difficult, and misdiagnoses and undiagnosed cases may be common. The American College of Rheumatology has developed and supported established diagnostic criteria for scleroderma since 1980. In 2001, it published diagnostic criteria requiring that a patient have either proximal diffuse sclerosis (skin tightness, thickening, non-pitting induration) or at least two of the following three symptoms: sclerodactyly of fingers or toes, digital pitting scars or loss of substance of finger pads (pulp loss), or bilateral basilar pulmonary fibrosis. In 2013, the diagnostic criteria for systemic sclerosis were updated in collaboration with the European League Against Rheumatism. Validation of the new criteria indicated a sensitivity of 91% and specificity of 92% vs 75% and 72%, respectively, for the former criteria in the same sample of patients. The new criteria rely on

_________________

1 Morphea occurs in adults, is characterized by having skin plaques that are oval shaped and ivory colored but with no involvement of internal organs, and generally improves without treatment. Linear scleroderma generally occurs in children and manifests as thick skin on arms or legs and can cause a limb to grow more slowly than its counterpart (NORD, 2014).

TABLE 4-1 Diagnostic Criteria for Systemic Sclerosis (Scleroderma)

| Item | Subitem(s) | Weight/Score* |

|

Skin thickening of the fingers of both hands extending proximal to the metacarpophalangeal joint (sufficient criteria) |

— |

9 |

|

Skin thickening of the fingers (only count the higher score) |

Puffy fingers Sclerodactyly of the fingers (distal to the metacarpophalangeal joints but proximal to the proximal interphalangeal joints) |

2 4 |

|

Fingertip lesions (only count the higher score) |

Digital tip ulcers Fingertip pitting scars |

2 3 |

|

Talengiectasia |

— |

2 |

|

Abnormal nailfold capillaries |

— |

2 |

|

Pulmonary arterial hypertension and/or interstitial lung disease (maximum score of 2) |

Pulmonary arterial hypertension Interstitial lung disease |

2 2 |

|

Raynaud’s phenomenon |

— |

3 |

|

SSc-related autoantibodies (anti-centromere, anti-topoisomerase I [anti-Scl-70], anti-RNA polymerase III) (maximum score is 3) |

Anti-centromere Anti-topoisomerase I Anti-RNA polymerase III |

3 |

NOTE: These criteria are applicable to any patient considered for inclusion in an SSc study. The criteria are not applicable to patients with skin thickening sparing the fingers or to patients who have a scleroderma-like disorder that better explains their manifestations (e.g., nephrogenic sclerosing fibrosis, generalized morphea, eosinophilic fasciitis, scleroderma diabeticorum, scleromyxedema, erythromyalgia, porphyria, lichen sclerosis, graft-versus-host disease, diabetic cheiroarthropathy). SSc = systemic sclerosis (scleroderma).

* The total score is determined by adding the maximum weight (score) in each category. Patients with a total score of ≥ 9 are classified as having definite SSc.

SOURCE: Reproduced from van den Hoogen et al. (2013) with permission from BMJ Publishing Group Ltd.

weights for various aspects of the disease; patients with a score of 9 or greater were classified as having systemic scleroderma (van den Hoogen et al., 2013). The new criteria are shown in Table 4-1.

Other important clinical features may include dysphagia, hypertension, and renal insufficiency; diarrhea with malabsorption; dyspnea secondary to the lung involvement; mucocutaneous telangiectasia on the face, lips, oral cavity, or hands; and erectile dysfunction (Varga, 2014).

A skin biopsy is generally not essential for confirmation, but blood tests or other studies may be helpful in confirming the diagnosis, as might consultation with a dermatologist or rheumatologist (Scleroderma Foundation, 2014). Treatment is limited to symptom management and efforts to improve quality of life; there is no cure (NORD, 2014; Scleroderma Foundation, 2014).

Although scleroderma is generally considered an autoimmune disease, a variety of occupational and environmental exposures have been associated with its development, including exposure to silica, vinyl chloride, and adulterated rapeseed oil (Mora, 2009). Scleroderma has also been reported with exposure to organic solvents and epoxy resins.

The mechanisms by which solvents induce autoimmune effects are poorly understood. The specific gaps in scientific knowledge include insufficient data on human immune suppression, on the effects of age and sex on susceptibility to TCE-related autoimmune effects, and on the effects of dose, duration, and timing of exposure (Weinhold, 2009). Most of the immune alterations associated with scleroderma involve antigen recognition, cell signaling, and cytokine production, but there may be multiple mechanisms by which environmental exposures initiate or contribute to the development of scleroderma (Mora, 2009).

Epidemiologic Studies of Exposure to Organic Solvents

In 2003, the Institute of Medicine (IOM) concluded that there was inadequate/insufficient evidence to determine whether an association exists between solvent exposure and scleroderma. On the basis of four additional studies of occupational solvent exposure (IOM, 2003), in 2009 the NRC concluded that the evidence of an association between mixed solvent exposure and scleroderma is limited/suggestive with some evidence pointing toward TCE exposure in particular (NRC, 2009).

Subsequent to the 2009 NRC report, reviews conducted by authoritative entities have also noted TCE’s autoimmune effects. In light of the new evidence, an expert panel of the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences examined the epidemiologic data available at the time and concluded that solvent exposure could contribute to the development of scleroderma (Miller et al., 2012). In 2011, EPA conducted a toxicological review of TCE, which noted:

The relation between systemic autoimmune diseases, such as scleroderma, and occupational exposure to TCE has been reported in several recent studies. A meta-analysis of scleroderma studies (Garabrant et al., 2003; Diot et al., 2002; Nietert et al., 1998) conducted by the EPA resulted in a statistically significant combined OR for any exposure in men (OR: 2.5, 95% CI: 1.1, 5.4), with a lower OR seen in women (OR: 1.2, 95% CI: 0.58, 2.6). (EPA, 2011, p. 4-427)

Two meta-analyses also examined the risk of scleroderma following solvent exposure. Barragan-Martinez et al. (2012) showed that organic solvent exposure is associated with systemic scleroderma (OR = 2.54, 95% CI [confidence interval] 1.23–5.14) and all autoimmune disorders (OR = 1.54, 95% CI 1.25–1.92) and that people with inherent risk factors (familial autoimmune disorders or genetic susceptibility) are particularly at risk. Cooper et al. (2009) used the concordance between human and animal studies to support the role of TCE in autoimmune diseases (skin hypersensitivity with systemic effects) and, based on an analysis of three case-control studies, reported an OR of 2.5 (95% CI 1.1–5.4) for scleroderma among TCE-exposed workers.

Additional literature reviews of epidemiologic evidence have supported the role of solvents or TCE as a risk factor for scleroderma (Mora, 2009) and autoimmune effects (Gilbert, 2010; Pollard, 2012; Pollard et al., 2010).

VA Guidance and Algorithm

As is the case with cancer, scleroderma’s diagnostic criteria are well established. Currently the VA guidance refers to the American College of Rheumatology criteria published in 2001; however, in 2013 the American College of Rheumatology adopted new criteria for systemic sclerosis (van den Hoogen et al., 2013) (see Table 4-1).

Because onset can occur at any time after exposure to a toxicant, any exposed veteran or family member is eligible for health benefits and accepted to the Camp Lejeune program regardless of when the disease was diagnosed. The core algorithm asks if a patient has an established diagnosis of scleroderma, and if the answer is yes, the patient is accepted into the program. Again, as with cancer, there is no separate algorithm for scleroderma; it is one step in the core algorithm.

Recommendations

The committee finds that the guidance and the core algorithm for scleroderma are reasonable and appropriate.

The committee recommends that VA update the guidance in accordance with the 2013 American College Rheumatology diagnostic criteria for scleroderma.

MISCARRIAGE AND INFERTILITY

This section provides separate descriptions of miscarriage and infertility and new research on each of them, including on their long-term health consequences. The committee then reviews the guidance and algorithm on miscarriage and infertility together since VA combined these outcomes into one algorithm, algorithm W Reproductive Health: Miscarriages and Infertility in Women.

Miscarriage

Overview

Miscarriage is a common term used to describe a spontaneous abortion. A spontaneous abortion is the naturally occurring expulsion of an embryo or fetus before viability. In clinical practice, expulsion before 20 weeks gestation is defined as a miscarriage (Storck, 2012). The rate at which miscarriages occur in the general population is difficult to estimate because many go undetected and unreported. Rates also vary greatly by gestational age; in one study, the highest reported rate was more than 20 miscarriages per 1,000 women-weeks up to week 13. Rates fall steadily with each additional week of gestation. Estimates suggest that between 11% and 22% of pregnancies between weeks 5 and 20 end in miscarriage (Ammon Avalos et al., 2012).

Common causes of miscarriage include maternal hormone problems, infections, physical and emotional trauma, being of an older age (there is a 50% chance of miscarriage in women over 45), smoking, illicit drug use, malnutrition, excessive caffeine, radiation exposure, and exposure to toxic substances, including the solvents to which residents at Camp Lejeune were exposed. Women who have had previous miscarriages are also at increased risk of additional miscarriages (25%, but this risk is only slightly increased compared to women who have not previously miscarried) (American Pregnancy Association, 2014).

A miscarriage may result in long-term psychologic and medical consequences. Mental health effects reported after miscarriage include depression, anxiety, and posttraumatic stress disorder (Frost and Condon, 1996). Depression and anxiety resulting from a previous miscarriage can be persistent, do not necessarily diminish after the birth of a subsequent healthy child (Blackmore et al., 2011), and differ from other kinds of perinatal loss (Adolfsson, 2011; Broen et al., 2004). Depression after miscarriage may be accompanied by long-lasting psychological, social, and health consequences (Beutel et al., 1995).

New Research

Recent research continues to support the association between solvent exposure and miscarriage. Miscarriage has been associated with occupational exposures to solvents in many industries, including wood processing (Viragh et al., 2014), pharmaceutical production (Attarchi et al., 2012), hairdressing (Peters et al., 2010), dry cleaning, semiconductor manufacturing, and petrochemical production (Kumar, 2011). In contrast to the occupational studies, a study on a general population cohort of women exposed to PCE-contaminated drinking water in Cape Cod did not find any meaningful associations between exposure and pregnancy loss (Aschengrau et al., 2009).

EPA’s toxicological review of PCE indicated that while some research is limited by imprecise estimates or an inability to evaluate confounding factors, occupational studies have generally reported maternal solvent exposure to be associated with elevated risks of miscarriage. However, studies of two populations did not observe an association (EPA, 2012). EPA’s review of TCE reported the same limitations for epidemiologic studies and found them to be not “highly informative” (EPA, 2011). ATSDR’s updated assessment of TCE reported little published evidence of an association between spontaneous abortion and TCE exposure (ATSDR, 2013). However, animal data show a consistent association between TCE exposure and prenatal loss (EPA, 2011).

Infertility

Overview

Infertility is defined as the failure to achieve a clinical pregnancy after 12 months or more of regular unprotected sexual intercourse. About 10% of women aged 15–44 have difficulty getting pregnant or staying pregnant (Eisenberg and Brumbaugh, 2009), but other estimates indicate a much lower prevalence (Mascarenhas et al., 2012; Thoma et al., 2013).

Female infertility may be caused by many factors affecting several different aspects of female reproduction. Polycystic ovary syndrome, hyperprolactinemia, eating disorders, excessive exercise, injury, and tumors all may

affect ovulation. Uterine or cervical abnormalities, such as uterine fibroids or other tumors, may distort the uterus or block fallopian tubes. Pelvic inflammatory disease, sexually transmitted diseases, and other conditions may cause inflammation of or damage to fallopian tubes. Endometriosis may affect the fallopian tubes, uterus, and ovaries. Primary ovarian insufficiency (early menopause) can be caused by immune disease, radiation therapy or chemotherapy, and smoking. Pelvic infections or surgeries can cause pelvic adhesions (scar tissue). Various health conditions including thyroid hormone abnormalities, cancer and cancer treatments, celiac disease, Cushing’s disease, sickle cell disease, kidney disease, diabetes, and genetic abnormalities, as well as certain medications can also reduce a woman’s fertility. Reduced fertility in women is also related to age, being overweight or underweight, and the use of tobacco and alcohol (Mayo Clinic, 2014). Exposure to environmental contaminants—and, in particular, PCE and TCE—can also affect fertility, for example by reducing fecundity and altering menstrual cycles (Dzubow et al., 2010; EPA, 2011).

Long-Term Effects of Infertility

Infertility may have an impact on the quality of life and mental health. Some studies indicate that infertility is associated with depression and loneliness, as well as with social isolation in older women (although the association may be confounded by marital status) (Gift and Spence, 2014). Psychological distress caused by infertility may be exacerbated by an extended duration and by infertility treatments (Greil, 1997).

VA Guidance and Algorithm

The guidance for female infertility and miscarriage is more specific with regard to the onset and occurrence of these effects than it is for other outcomes. Exposed veterans and family members who experienced or were diagnosed with these problems during their time at Camp Lejeune are eligible for health benefits if they require ongoing medical treatment. The guidance clearly states that there is no evidence to support an increased risk of female infertility or miscarriage after the exposure ended or after an individual moved away from Camp Lejeune. Thus, current infertility or a miscarriage in a woman who was a child, adolescent, or young adult while at Camp Lejeune is excluded.

Furthermore, the guidance states that there is no evidence that the exposure of a fetus to solvents increases the risk of that person being infertile when he or she becomes a reproductively mature adult. This excludes any claims of miscarriage or infertility from the offspring of women who were pregnant while exposed to contaminated drinking water at Camp Lejeune between 1957 and 1987.

The guidance focuses on women with complications secondary to past infertility or miscarriage that require continued treatment. These complications would have developed or persisted between 26 and 56 years after problems with infertility and miscarriage occurred while at Camp Lejeune. Algorithm W begins with the identification of past health record data for pregnancy, miscarriage, or infertility dating to 1957–1987. There must be documentation that the infertility or miscarriage occurred during residence on Camp Lejeune. It is possible that medical records from that period may not be available. In these cases, it is important that VA encourage informed clinical judgment to identify veterans or family members with persistent problems that may have resulted from miscarriage or infertility that occurred concurrent with exposure to drinking water at Camp Lejeune. The next step in algorithm W asks the clinician to determine if there are ongoing “medical complications” or “medical problems” that might be attributed to the infertility or miscarriage that occurred at that time. Those health conditions, including mental health problems, are covered by the Camp Lejeune program if they can be related to miscarriage or infertility that occurred while in residence at Camp Lejeune.

Recommendations

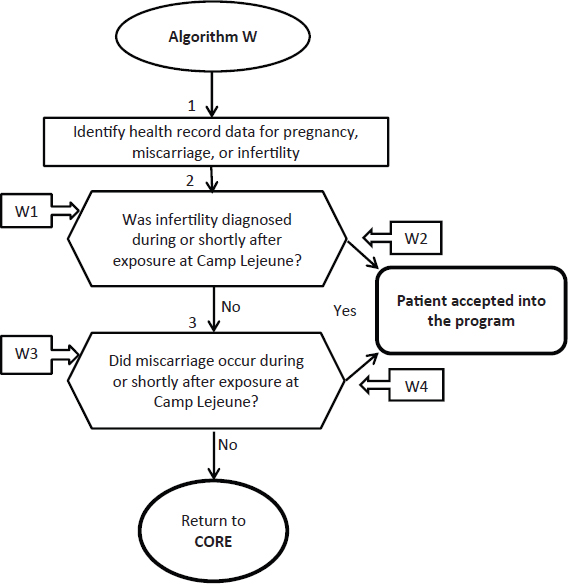

The committee finds the guidance and algorithm for miscarriage and infertility to be generally appropriate. Suggested revisions to algorithm W are shown in Figure 4-1.

FIGURE 4-1 Revised algorithm W—Reproductive health: miscarriage and infertility in women.

ANNOTATIONS FOR ALGORITHM W:

W1—Infertility was diagnosed after leaving Camp Lejeune. There is currently no scientific evidence to support an association with chronic female infertility after cessation of exposure to solvents. Similarly the NRC report found no evidence that exposure to organic solvents while in utero increases the risk for adverse fertility effects as a reproductively mature adult. Applicant does not have female infertility that is covered by the Camp Lejeune program.

W2—Applicant has a physical or mental health condition requiring continued medical treatment from female infertility that occurred while b e i n g exposed to contaminated water at Camp Lejeune. The medical condition is related to the infertility experienced during residence at Camp Lejeune. Applicant accepted into the Camp Lejeune program.

W3—Miscarriage occurred after leaving Camp Lejeune. Current scientific evidence suggests that there are no persistent effects of solvent exposure on miscarriage or fetal loss. Applicant does not have a miscarriage that is covered by the Camp Lejeune program. Applicant is not accepted into the Camp Lejeune program at this time.

W4—Applicant has a physical or mental health condition requiring continued medical treatment from a miscarriage experienced while exposed to contaminated water at Camp Lejeune. Clinicians should carefully assess whether continued health care is needed for chronic, persistent medical problems associated with a miscarriage that occurred during solvent exposure at Camp Lejeune; if care needs are persistent, the applicant is accepted into the Camp Lejeune program.

The committee recommends that throughout the guidance and algorithm VA refer to “physical and mental health conditions” related to prior infertility or miscarriage, rather than “medical conditions,” “medical problem,” or “medical treatment.”

HEPATIC STEATOSIS

Overview

Hepatic steatosis, commonly referred to as fatty liver, is the initial pathologic manifestation of fatty liver disease. It is an accumulation of lipids in hepatocytes (Day, 2006; Kaiser et al., 2012), which leads to an inflammatory response in the liver which in turn may progress to fibrosis, cirrhosis (Wahlang et al., 2013), and liver cancer (Du and Wang, 1998; Jiang et al., 2014). Hepatic steatosis is associated with a variety of other conditions, including type 2 diabetes; metabolic syndrome; hepatitis; hyperlipidemia; other less common liver diseases, such as Weber–Christian syndrome, Wilson disease, and lipodystrophy (Angulo, 2002; Bayard et al., 2006); starvation (McAvoy et al., 2006); severe weight loss such as experienced after bariatric surgery (Mohanty, 2006); and increased cardiovascular risk (Anstee et al., 2013; Bhatia et al., 2012a,b). Hepatic steatosis may also result from the use of some medications (e.g., chemotherapeutic agents) and from exposure to some solvents (such as TCE, PCE, and chloroform), halogenated hydrocarbons (carbon tetrachloride, vinyl chloride), volatile organic mixtures, pesticides, and nitro-organic compounds (Wahlang et al., 2013). Susceptibility to hepatic steatosis is influenced by a number of factors including genetics, alcohol consumption, the use of prescription medications, and nutritional factors such as obesity (Wahlang et al., 2013). Steatosis occurs in 90% of those who consume 16 g of alcohol or more per day (Wahlang et al., 2013). (Note: One “standard” drink [e.g., 5 ounces of wine, 12 ounces of regular beer, 7–8 ounces of malt beer, or 1.5 ounces of 80-proof spirits] contains roughly 14 grams of pure alcohol.2) Hepatic steatosis may also occur in up to 92% of obese adults (WGO, 2012).

Drugs reported to cause fatty liver include methotrexate, tamoxifen, corticosteroids, griseofulvin, diltiazem, anti-retroviral therapy, nifedipine (Mohanty, 2006), valproate (Depakote), high doses of intravenous tetracycline or amiodarone, and certain herbs (for example, the Chinese herb jin bu huan, used as a sedative and pain reliever) (Lee, 2014).

Most patients who present with hepatic steatosis have elevated liver enzyme levels but may be asymptomatic; others may complain of fatigue and right upper quadrant abdominal fullness or pain. Up to 50% of patients with steatosis have hepatomegaly (Sanyal, 2002). A probable diagnosis can be established by imaging studies including ultrasound, computerized tomography (CT), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). A definitive diagnosis is established by a pathological finding on liver biopsy, accompanied by the exclusion of other potential causes (Angulo, 2002).

Treatment focuses on removing the inciting agent (such as alcohol or a toxic exposure) or reducing risk factors related to associated conditions, including weight loss, exercise, and the treatment of diabetes and hyperlipidemia. No medications intended to protect hepatocytes have been found to be effective in treating steatosis (e.g., ursodexycholic acid, vitamin E, betaine) (Bayard et al., 2006) and there are no U.S. Food and Drug Administration–approved medications for the treatment of fatty liver disease. The prognosis for hepatic steatosis is generally benign and the condition reversible, but if it persists, more severe pathologies can develop, such as fibrosis, cirrhosis (such as cryptogenic cirrhosis), and liver cancer (Kaiser et al., 2012; McAvoy et al., 2006).

VA Guidance and Algorithm

The VA guidance states that in evaluating whether a veteran or a family member has hepatic steatosis that may be the result of exposure to drinking water at Camp Lejeune, the clinician should first consider whether it is more likely than not that the patient’s hepatic steatosis is the result of a “known etiology.” The most common causes include obesity and significant alcohol consumption; less common causes include dyslipidemia; metabolic

_________________

2 See http://niaaa.nih.gov/alcohol-health/overview-alcohol-consumption/standard-drink (accessed November 5, 2014).

syndrome; diabetes; hepatitis; other liver diseases such as hepatitis C genotype 3 and Wilson’s disease; and some medications.

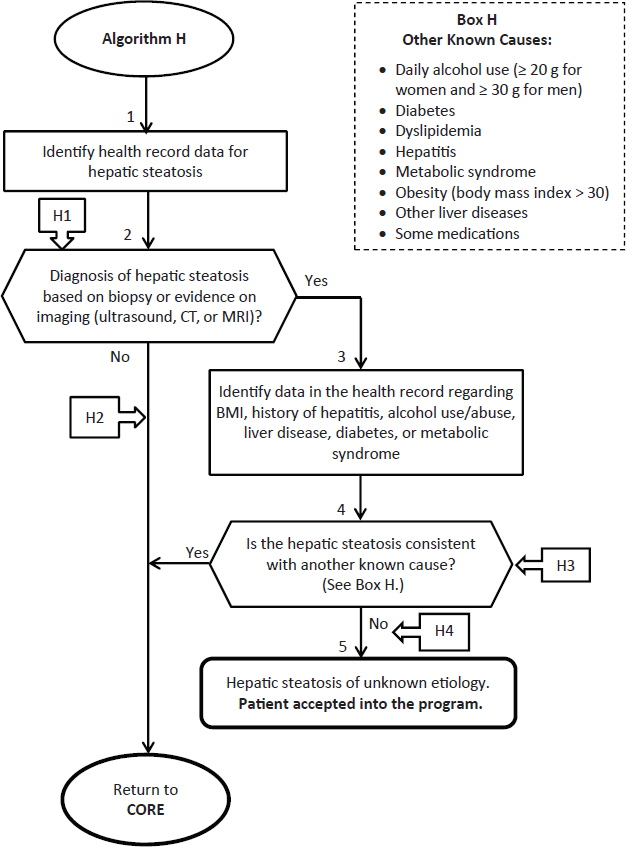

Algorithm H begins with a diagnosis of hepatic steatosis based on medical records and liver biopsy or evidence from imaging studies (e.g., ultrasound, CT, or MRI). The committee notes that ideally a clinician would also evaluate any abnormal liver function results from tests that were conducted while the individual resided at Camp Lejeune or shortly after; however, the committee emphasizes that these test results are unlikely to be available because toxicant-induced injury soon after exposure would likely have been asymptomatic, and such tests would not have been conducted.

The guidance states that hepatic steatosis may occur during or shortly after acute exposure to solvents. In most cases hepatic steatosis associated with solvent exposure is expected to resolve after the exposure ceases; and its onset is unlikely to occur many months or years later. Thus, the guidance suggests that clinicians carefully consider the onset and duration of the condition when evaluating its potential association with drinking water at Camp Lejeune. However, neither the guidance nor algorithm H provide further information on how to assess whether the onset and duration support an association between steatosis and exposure to solvents at Camp Lejeune. The committee notes that the published literature does not provide definitive evidence regarding the onset and duration of steatosis and its resolution after the exposure ends.

The guidance specifies that if a patient’s history is consistent with a known cause of hepatic steatosis, the patient would not be covered by the Camp Lejeune program. Conversely, Camp Lejeune veterans and family members with hepatic steatosis of unclear or unknown etiology should be covered by the program. The guidance on hepatic steatosis concludes by noting that “if a patient’s clinical course is atypical or progresses faster than expected, then exacerbation by TCE, PCE or other organic solvents from Camp Lejeune should be considered” (page 10). The committee was unable to find evidence to support this statement.

The third step in algorithm H asks the clinician to determine if there are diagnoses or medical record data indicating other likely etiologies for the hepatic steatosis. Possible causes to be considered include obesity, alcohol abuse, dyslipidemia, metabolic syndrome, diabetes, hepatitis, and other liver diseases such as hepatitis C genotype 3 and Wilson’s disease. Medical record data to be considered by the clinician include elevated body mass index, a history of hepatitis, alcohol use, and liver disease or metabolic syndrome. If a patient’s hepatic steatosis is not consistent with those other possible causes, then the patient is accepted to the Camp Lejeune program.

In considering other etiologies, the algorithm suggests a threshold of 20 grams of alcohol per day in women and 30 grams per day in men to indicate alcohol-related fatty liver disease (AFLD). Unfortunately, AFLD is pathologically indistinguishable from non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, or toxicant-associated fatty liver disease (TAFLD) (Wahlang et al., 2013). To distinguish AFLD from other types of fatty liver disease, two cutoffs based on alcohol consumption have been proposed: two drinks per day or greater (Bayard et al., 2006), or 20 g alcohol/day for women and 30 g alcohol/day for men (Adams et al., 2005). Neither TAFLD nor toxicant-associated steatohepatitis—a more severe form of TAFLD characterized by hepatic steatosis, inflammatory infiltrate, and in some cases fibrosis—is associated with significant alcohol consumption or obesity.

Recommendations

The application of algorithm H for hepatic steatosis is challenging because of the high prevalence of other potential causes of hepatic steatosis in the general population, such as obesity, alcohol use, diabetes, dyslipidemia, medications, and other exposures. Thus, it is important that VA encourage informed clinical judgment to identify veterans or family members with hepatic steatosis that may have resulted from exposure to drinking water at Camp Lejeune based on its persistence since residing at Camp Lejeune or the absence of other more likely causes. In contrast, when other causes are present, steatosis is not likely to be attributable to exposure at Camp Lejeune.

The phrase in the guidance “[M]oreover if a patient’s clinical course is atypical or progresses faster than expected, then exacerbation by TCE, PCE or other organic solvents from Camp Lejeune should be considered” is not consistent with the known pathogenesis of TAFLD. In particular, there is no evidence that solvent exposure would result in an atypical presentation or rapid progression of hepatic steatosis at a later date.

Based on the evidence, the committee recommends that VA delete the phrase “atypical or progresses faster than expected” in the clinical guidance. The committee further recommends that VA replace the term “alcohol abuse,” listed among the other causes of hepatic steatosis in the clinical guidance and algorithm, with “alcohol use ≥ 20 g/day for women or ≥ 30 g/d for men.”

There are several commonly used medications that are known to cause fatty liver, including methotrexate, tamoxifen, corticosteroids, griseofulvin, diltiazem, anti-retroviral therapy, amiodarone, nifedipine, and valproate.

The committee recommends that VA include “some medications” in the list of other causes in algorithm H and that examples of those medications be listed in the text of the clinical guidance.

Suggested revisions are shown in Figure 4-2.

ANNOTATIONS FOR ALGORITHM H:

H1—Hepatic steatosis (fatty liver) is an accumulation of lipids (triglycerides and other lipids) in the liver hepatocytes. Patients are often asymptomatic. It is often diagnosed as an incidental finding on routine medical exams with blood tests revealing abnormal liver function tests. Liver biopsy is the only definitive test to confirm diagnosis, exclude other causes, assess extent and predict prognosis. In most instances, it will be possible to identify the existence of hepatic steatosis and to define the extent of the condition using diagnostic imaging techniques (ultrasound, CT, or MRI).

H2—Applicant does not have clinical evidence (positive biopsy, CT, MRI, or ultrasound test) of hepatic steatosis at this time.

H3—The most common known causes of steatosis are obesity and alcohol abuse. Other possible causes include dyslipidemia, metabolic syndrome, diabetes, hepatitis or other liver disease, and some medications such as methotrexate, tamoxifen, corticosteroids, griseofulvin, diltiazem, anti-retroviral therapy, amiodarone, nifedipine, and valproate.

Applicant has clinical evidence of hepatic steatosis due to a cause other than exposure at Camp Lejeune. Fatty liver disease can be divided into two main categories: alcohol-related fatty liver disease and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). Consumption of < 20 gm alcohol per day in women and < 30 gm in men suggests a diagnosis of NAFLD. NAFLD is associated with obesity and with abnormal glucose tolerance and dyslipidemia, and has been described as the hepatic manifestation of the metabolic syndrome. Fatty liver develops in 46% to 90% of heavy alcohol users, and in up to 94% of obese individuals. Thus, hepatic steatosis in women who drink ≥ 20 g of alcohol or in men who drink ≥ 30 g of alcohol per day or who are obese (that is, have a body mass index of > 30), is not likely due to exposure to the contaminated water at Camp Lejeune. A typical drink contains 14 g of alcohol (http://www.niaaa.nih.gov/alcohol-health/overview-alcohol-consumption/standard-drink [accessed November 5, 2014]).

Current hepatic steatosis is due to another cause other than exposure to contaminated water at Camp Lejeune. Applicant does not have a condition eligible for coverage by the Camp Lejeune program at this time.

H4—Applicant has hepatic steatosis of unknown etiology. Applicant is accepted into the Camp Lejeune program.

FIGURE 4-2 Revised algorithm H—Hepatic steatosis.

REFERENCES

Adams, L. A., P. Angulo, and K. D. Lindor. 2005. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Canadian Medical Association Journal 172(7):899-905.

Adolfsson, A. 2011. Meta-analysis to obtain a scale of psychological reaction after perinatal loss: Focus on miscarriage. Psychology Research Behavior Management 4:29-39.

Ammon Avalos, L., C. Galindo, and D. K. Li. 2012. A systematic review to calculate background miscarriage rates using life table analysis. Birth Defects Research Part A Clinical Molecular Teratology 94(6):417-423.

Angulo, P. 2002. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. New England Journal of Medicine 346(16):1221-1231.

Anstee, Q. M., G. Targher, and C. P. Day. 2013. Progression of NAFLD to diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular disease or cirrhosis. Nature Reviews, Gastroenterology and Hepatology 10(6):330-344.

APA (American Pregnancy Association). 2014. Miscarriage. Available at americanpregnancy.org/pregnancycomplications/miscarriage.html (accessed July 30, 2014).

Aschengrau, A., J. M. Weinberg, L. G. Gallagher, M. R. Winter, V. M. Vieira, T. F. Webster, and D. M. Ozonoff. 2009. Exposure to tetrachloroethylene-contaminated drinking water and the risk of pregnancy loss. Water Quality Exposure and Health 1(1):23-34.

ATSDR (Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry). 2013. Addendum to the Toxicological Profile for Trichloroethylene. Atlanta, GA: Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry, Division of Toxicology and Human Health Sciences. Available at www.atsdr.cdc.gov/toxprofiles/tce_addendum.pdf (accessed January 2, 2015).

Attarchi, M. S., M. Ashouri, Y. Labbafinejad, and S. Mohammadi. 2012. Assessment of time to pregnancy and spontaneous abortion status following occupational exposure to organic solvents mixture. International Archives of Occupation and Environmental Health 85(3):295-303.

Barragan-Martinez, C., C. A. Speck-Hernandez, G. Montoya-Ortiz, R. D. Mantilla, J. M. Anaya, and A. Rojas-Villarraga. 2012. Organic solvents as risk factor for autoimmune diseases: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Public Library of Science One 7(12).

Bayard, M., J. Holt, and E. Boroughs. 2006. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. American Family Physician 73(11):1961-1968.

Beutel, M., R. Deckardt, M. von Rad, and H. Weiner. 1995. Grief and depression after miscarriage: Their separation, antecedents, and course. Psychosomatic Medicine 57(6):517-526.

Bhatia, L. S., N. P. Curzen, and C. D. Byrne. 2012a. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and vascular risk. Current Opinions in Cardiology 27(4):420-428.

Bhatia, L. S., N. P. Curzen, P. C. Calder, and C. D. Byrne. 2012b. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: A new and important cardiovascular risk factor? European Heart Journal 33(10):1190-1200.

Blackmore, E. R., D. Cote-Arsenault, W. Tang, V. Glover, J. Evans, J. Golding, and T. G. O’Connor. 2011. Previous prenatal loss as a predictor of perinatal depression and anxiety. British Journal of Psychiatry 198(5):373-378.

Bove, F. J., P. Z. Ruckart, M. Maslia, and T. C. Larson. 2014a. Evaluation of mortality among marines and Navy personnel exposed to contaminated drinking water at USMC Base Camp Lejeune: A retrospective cohort study. Environmental Health 13:10.

Bove, F. J., P. Z. Ruckart, M. Maslia, and T. C. Larson. 2014b. Mortality study of civilian employees exposed to contaminated drinking water at USMC Base Camp Lejeune: A retrospective cohort study. Environmental Health 13:68.

Broen, A. N., T. Moum, A. S. Bodtker, and O. Ekeberg. 2004. Psychological impact on women of miscarriage versus induced abortion: A 2-year follow-up study. Psychosomatic Medicine 66(2):265-271.

Christensen, K. Y., D. Vizcaya, H. Richardson, J. Lavoue, K. Aronson, and J. Siemiatycki. 2013. Risk of selected cancers due to occupational exposure to chlorinated solvents in a case-control study in Montreal. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine 55(2):198-208.

Cooper, G. S., S. L. Makris, P. J. Nietert, and J. Jinot. 2009. Evidence of autoimmune-related effects of trichloroethylene exposure from studies in mice and humans. Environmental Health Perspective 117(5):696-702.

Day, C. P. 2006. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: Current concepts and management strategies. Clinical Medicine 6(1):19-25.

de Gonzalez, A. B., A. I. Apostoaei, L. H. S. Veiga, P. Rajaraman, B. A. Thomas, F. O. Hoffman, E. Gilbert, and C. Land. 2012. RadRAT: A radiation risk assessment tool for lifetime cancer risk projection. Journal of Radiological Protection 32(3):205-222.

Du, C. L., and J. D. Wang. 1998. Increased morbidity odds ratio of primary liver cancer and cirrhosis of the liver among vinyl chloride monomer workers. Occupational and Environmental Medicine 55(8):528-532.

Dzubow, R. B., S. Makris, C. S. Scott, and S. Barone, Jr. 2010. Early lifestage exposure and potential developmental susceptibility to tetrachloroethylene. Birth Defects Research Part B—Developmental and Reproductive Toxicology 89(1):50-65.

Eisenberg, E., and K. Brumbaugh. 2009. Frequently asked questions: Infertility. Department of Health and Human Services. Available at www.womenshealth.gov/publications/our-publications/fact-sheet/infertility.pdf (accessed January 22, 2015).

EPA (U.S. Environmental Protection Agency). 2011. Toxicological review of tricholorethylene (CAS No. 79-01-6) in support of summary information on the Integrated Risk Information System (IRIS). EPA/635/R-08/011F. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

EPA. 2012. Toxicological review of tetracholorethylene (perchloroethylene) (CAS No. 127-18-4) in support of summary information on the Integrated Risk Information System (IRIS). EPA/635/R-08/011F. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

Frost, M., and J. T. Condon. 1996. The psychological sequelae of miscarriage: A critical review of the literature. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry 30(1):54-62.

Gift, T., and O. Spence. 2014. Abstract: Infertility and Quality of Life: Findings from a Literature Review. Paper read at CDC STD Prevention Conference, June 9-12, 2014, Atlanta, GA.

Gilbert, K. M. 2010. Xenobiotic exposure and autoimmune hepatitis. Hepatitis Research and Treatment 248157.

Greil, A. L. 1997. Infertility and psychological distress: A critical review of the literature. Social Science & Medicine 45(11):1679-1704.

Hansen, J., M. Sallmen, A. I. Selden, A. Anttila, E. Pukkala, K. Andersson, I. L. Bryngelsson, O. Raaschou-Nielsen, J. H. Olsen, and J. K. McLaughlin. 2013. Risk of cancer among workers exposed to trichloroethylene: Analysis of three Nordic cohort studies. Journal of the National Cancer Institute 105(12):869-877.

Howard, J. 2013. Minimum Latency & Types or Categories of Cancer. World Trade Center Health Program, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

IARC (International Agency for Research on Cancer). 2014a. Tetrachloroethylene. In IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans, Vol. 106. Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer.

IARC. 2014b. Trichloroethylene. In IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans, Vol. 106. Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer.

IOM (Institute of Medicine). 2003. Gulf War and health, Volume 2: Insecticides and solvents. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

ISN (International Scleroderma Network). Undated. Systemic Sclerosis: CREST Syndrome. Available at www.sclero.org/medical/about-sd/types/systemic/limited/crest/a-to-z.html (accessed September 17, 2014).

Jiang, C. M., C. W. Pu, Y. H. Hou, Z. Chen, M. Alanazy, and L. Hebbard. 2014. Non alcoholic steatohepatitis a precursor for hepatocellular carcinoma development. World Journal of Gastroenterology 20(44):16464-16473.

Kaiser, J. P., J. C. Lipscomb, and S. C. Wesselkamper. 2012. Putative mechanisms of environmental chemical-induced steatosis. International Journal of Toxicology 31(6):551-563.

Kumar, S. 2011. Occupational, environmental and lifestyle factors associated with spontaneous abortion. Reproductive Sciences 18(10):915-930.

Lawrence, R. C., C. G. Helmick, F. C. Arnett, R. A. Deyo, D. T. Felson, E. H. Giannini, S. P. Heyse, R. Hirsch, M. C. Hochberg, G. G. Hunder, M. H. Liang, S. R. Pillemer, V. D. Steen, and F. Wolfe. 1998. Estimates of the prevalence of arthritis and selected musculoskeletal disorders in the United States. Arthritis and Rheumatism 41(5):778-799.

Lee, D. 2014. Drug induced liver disease: Steatosis (fatty liver). Available at www.medicinenet.com/drug_induced_liver_disease/page7.htm#steatosis_fatty_liver (accessed August 13, 2014).

Lipworth, L., J. S. Sonderman, M. T. Mumma, R. E. Tarone, D. E. Marano, J. D. Boice, Jr., and J. K. McLaughlin. 2011. Cancer mortality among aircraft manufacturing workers: An extended follow-up. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine 53(9):992-1007.

Mascarenhas, M. N., S. R. Flaxman, T. Boerma, S. Vanderpoel, and G. A. Stevens. 2012. National, regional, and global trends in infertility prevalence since 1990: A systematic analysis of 277 health surveys. PLoS Medicine 9(12):e1001356.

Mayo Clinic. 2013. Scleroderma. Available at www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/scleroderma/basics/causes/con-20021378 (accessed August 4, 2014).

Mayo Clinic. 2014. Infertility basics. Available at www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/infertility/basics/causes/con-20034770 (accessed July 30, 2014).

McAvoy, N. C., J. W. Ferguson, I. W. Campbell, and P. C. Hayes. 2006. Review: Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: Natural history, pathogenesis and treatment. British Journal of Diabetes & Vascular Disease 6:251-260.

Miller, F. W., L. Alfredsson, K. H. Costenbader, D. L. Kamen, L. M. Nelson, J. M. Norris, and A. J. De Roos. 2012. Epidemiology of environmental exposures and human autoimmune diseases: Findings from a National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences Expert Panel Workshop. Journal of Autoimmunity 39(4):259-271.

Mohanty, S. R. 2006. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) (fatty liver). University of Chicago. Available at www.liverfoundation.org/downloads/alf_download_194.pdf (accessed July 28, 2014).

Mora, G. F. 2009. Systemic sclerosis: Environmental factors. Journal of Rheumatology 36(11):2383-2396.

Mori, Y., V. M. Kahari, and J. Varga. 2002. Scleroderma-like cutaneous syndromes. Current Rheumatology Reports 4(2):113-122.

NORD. 2014. Scleroderma. Available at www.rarediseases.org/rare-disease-information/rare-diseases/byID/69/viewFullReport (accessed August 4, 2014).

NRC (National Research Council). 2009. Contaminated water supplies at Camp Lejeune: Assessing potential health effects. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Peters, C., M. Harling, M. Dulon, A. Schablon, J. Torres Costa, and A. Nienhaus. 2010. Fertility disorders and pregnancy complications in hairdressers—A systematic review. Journal of Occupational Medicine and Toxicology 5:24.

Pollard, K. M. 2012. Gender differences in autoimmunity associated with exposure to environmental factors. Journal of Autoimmunity 38(2-3):J177-J186.

Pollard, K. M., P. Hultman, and D. H. Kono. 2010. Toxicology of autoimmune diseases. Chemical Research in Toxicology 23(3):455-466.

Ruckart, P. Z., F. J. Bove, and M. Maslia. 2013. Evaluation of exposure to contaminated drinking water and specific birth defects and childhood cancers at Marine Corps Base Camp Lejeune, North Carolina: A case-control study. Environmental Health 12:104.

Sanyal, A. J. 2002. AGA technical review on nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Gastroenterology 123(5):1705-1725.

Scleroderma Foundation. 2014. What Is Scleroderma? Available at www.scleroderma.org/site/PageNavigator/patients_whatis.html#.U-DiMGNY8RF (accessed August 4, 2014).

Scott, C. S., and J. Jinot. 2011. Trichloroethylene and cancer: systematic and quantitative review of epidemiologic evidence for identifying hazards. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 8(11):4238-4272.

Storck, S. 2012. Miscarriage. Available at www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/ency/article/001488.htm (accessed September 17, 2014).

Thoma, M. E., A. C. McLain, J. F. Louis, R. B. King, A. C. Trumble, R. Sundaram, and G. M. Buck Louis. 2013. Prevalence of infertility in the United States as estimated by the current duration approach and a traditional constructed approach. Fertility and Sterility 99(5):1324-1331.

van den Hoogen, F., D. Khanna, J. Fransen, S. R. Johnson, M. Baron, A. Tyndall, M. Matucci-Cerinic, R. P. Naden, T. A. Medsger, Jr., P. E. Carreira, G. Riemekasten, P. J. Clements, C. P. Denton, O. Distler, Y. Allanore, D. E. Furst, A. Gabrielli, M. D. Mayes, J. M. van Laar, J. R. Seibold, L. Czirjak, V. D. Steen, M. Inanc, O. Kowal-Bielecka, U. Muller-Ladner, G. Valentini, D. J. Veale, M. C. Vonk, U. A. Walker, L. Chung, D. H. Collier, M. E. Csuka, B. J. Fessler, S. Guiducci, A. Herrick, V. M. Hsu, S. Jimenez, B. Kahaleh, P. A. Merkel, S. Sierakowski, R. M. Silver, R. W. Simms, J. Varga, and J. E. Pope. 2013. 2013 classification criteria for systemic sclerosis: An American College of Rheumatology/European League against Rheumatism collaborative initiative. Arthritis and Rheumatology 65(11):2737-2747.

Varga, J. 2014. Scleroderma: Diagnosis and differential diagnosis of systemic sclerosis (scleroderma) in adults. Available at http://www.uptodate.com/contents/diagnosis-and-differential-diagnosis-of-systemic-sclerosis-scleroderma-in-adults (accessed August 13, 2014).

Viragh, E. J., K. A. Viragh, and J. Laczka. 2014. Abstract: Prevalence of spontaneous abortion in workers in the wood-processing industry. Paper read at Challenges for Occupational Epidemiology in the 21st Century EPICOH, June 24–27, 2014, Chicago, IL.

Wahlang, B., J. I. Beier, H. B. Clair, H. J. Bellis-Jones, K. C. Falkner, C. J. McClain, and M. C. Cave. 2013. Toxicant-associated steatohepatitis. Toxicologic Pathology 41(2):343-360.

Walters, T. 2014a. Presentation and Charge to Committee: Institute of Medicine Committee to Define Clinical Terms in P.L. 112-154 & Review Clinical Guidelines. Washington, DC, May 15, 2014.

Walters, T. 2014b. Questions posed by IOM committee and subsequent answers from Dr. Terry Walters, U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, July 8, 2014.

Weinhold, B. 2009. A clearer view of TCE: Evidence supports autoimmune link. Environmental Health Perspective 117(5):A210.

WGO (World Gastroenterology Organisation). 2012. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. World Gastroenterology Organization Global Guidelines. Available at www.worldgastroenterology.org/assets/export/userfiles/2012_NASH%20and%20NAFLD_Final_long.pdf (accessed August 13, 2014).