3

Financing for Outcomes and Equity

As the early childhood development community continues to learn more about what works to promote growth and development, speakers noted a need to finance successful programs beyond the pilot or subnational stage to the national or regional level. Both globally and nationally, there is recognition at the country level of the importance of early childhood development, but gaps still exist in financing these programs. Speakers discussed financing programs to reach marginalized populations, to reduce disparities among recipients, and to support child rights.

KEYNOTE: WHAT IT MEANS TO FINANCE INVESTMENTS IN YOUNG CHILDREN1

Sumit Bose, former finance secretary and member of the Expenditure Management Commission of the government of India, presented the keynote address, speaking about lessons learned from India’s commitment to financing investments for its sizable population of children under age 8. India is home to the largest number of children in the world; nearly one in five children between birth to 18 years lives in the country. While this has spurred the government to invest in education, care, and health, many children continue to fall through the cracks each year, for both financial and nonfinancial reasons. Bose framed his remarks by describing a feder-

______________

1 This section summarizes information presented by Sumit Bose, former finance secretary and member of the Expenditure Management Commission of the Government of India.

alist system of governance in India, in which both the central government and state and local governments are assigned specific functions, which include both policy and regulatory duties. Taxation mostly lies within the realm of the central government, and every 5 years a finance commission is convened to determine how to allocate tax revenue among government levels.

Financing Education

Bose stated that in the realm of elementary education, for example, financing is shared between the central government and the states, with the states obligated to provide free and compulsory education up to age 14, per a court ruling that education is a fundamental right. This commitment began in the 1990s, with funding from external donors such as the World Bank, and it was formalized in a program for universal education in 2001 as determined by a constitutional amendment, according to Bose. In 2009, the Right to Education law was passed, providing free and compulsory education for children and including provisions for resources in the form of teachers, classrooms, and schools. It also reserved 25 percent of private school admissions for disadvantaged groups, reimbursed at a level equal to per-child expenditure at equivalent government schools. Bose stated that in the past decade, funding for universal education has increased both at the central government and state government level, with state governments now taking on up to 35 percent of expenses. He described this program as a successful undertaking made possible by a commitment to financing: in 2004, to fund primary education, the government levied a central tax at the rate of 2 percent. Similar measures have been duplicated at the state and municipal level. Bose pointed out that in the state of Madhya Pradesh, for example, the Indore municipality levied a surcharge of 20 percent on property taxes to fund school infrastructure.

Bose noted the success of this financing scheme, including the ability to raise both the relative level of funding (as a percentage in relation to an increase in the federal budget) and absolute level of funding (the overall number of dollars), but cautioned that increasing levels of central government and external donor expenditure could result in “substitution funding.” For Bose, there is a danger in the federal government providing funds to state governments without the state governments maintaining their level of funding. However, Bose said, this problem was addressed in the latest Finance Commission’s report, which mandated a minimum growth rate of 8 percent in state budgets for elementary education in order to receive central government funds. He also noted that additional means of funding school education, through private individuals and institutions, are encouraged via various tax exemptions.

Financing Nutrition in Education and Care Settings

Bose stated that in 1995, India launched a midday meal program in primary schools in parts of the country. As they did for education, civil society organizations organized to promote the concept of a right to food, which resulted in a series of Supreme Court decisions in 2001, 2004, and 2006 that first recognized that right, and also called for the universal provision of the midday meal program as well as the expansion of the Integrated Child Development Service (ICDS) for children under age 6. Bose noted that following the 2006 decision, central government funding for the midday meal skyrocketed from 6 billion rupees to 132 billion rupees to cover the expansion of services, with states providing an additional 25 percent of funding.

Bose went on to describe the ICDS, which provides supplementary nutrition, preschool education, health and nutrition services for children and mothers, immunizations, primary health care, and referral services. The ICDS, initiated in 1975 and expanded through later provision, is the largest early child development program in the world, reaching more than 80 million children and 20 million mothers. Services are provided through Anganwadi centers, of which there are more than 1 million. Anganwadi centers are located in communities and are the main interface for women and their children. Through the 2013 National Food Security Bill, the Anganwadi centers are authorized to provide free meals for women, children, and adolescent girls, and cash transfers as part of maternity benefits (see Box 3-1 for additional information on Anganwadi centers). Bose stated that the current budget for the ICDS is 18 billion rupees.

Linking Financing to Outcomes

Bose also discussed the limitations to financing large-scale child development schemes. In particular, ensuring that funding reaches the appropriate recipients is dependent on robust and transparent institutions and governance structures. Sometimes, because of the pressure to create short-term solutions, there is a failure to develop sustainable institutions. At the same time, redundancies develop, as now in India. He said there is a need to merge such institutions to ensure transparency.

These limitations can be barriers to achieving the ultimate goal of financing social welfare schemes that lead to positive outcomes in child development. Despite various attempts at ensuring the efficiency of funding, Bose stated that sometimes expenditures do not convert into outcomes, and “those who control the purse strings” must be shown that these expenditures produce the desired results. In situations where this is not true, Bose argued that stakeholders need to be ready to respond with corrective action in both how the money flows and how the pro-

BOX 3-1

Anganwadi Centersa

Anganwadi centers were established in 1975 as part of the Integrated Child Development Services scheme with the goals of improving the nutrition, health, and development of children ages 0 to 6 and strengthening caregivers’ ability to monitor the well-being of children in low-income families. These aims are achieved by providing a package of services, including

- supplementary nutrition,

- immunization,

- health check-ups,

- referral services,

- preschool nonformal education, and

- nutrition and health education.

Currently there are more than 1 million Anganwadi centers across India, employing 1.8 million workers, most of whom are women. According to government figures, centers reach approximately 58.1 million children and 10.23 million pregnant or lactating women.

______________

a All information contained in this box is provided by http://www.aanganwadi.org (accessed October 20, 2014).

grams operate. There is political conviction that funding child programs is important, but it has to translate into results.

Although funding child development programs in India has been a success, Bose questioned whether that was sufficient to see improved child growth and development outcomes. He noted that despite the increase in numbers of schools and enrollment of children, there has been a decline in reading levels, math skills, and even attendance. One problem, he observed, is that top-down resourcing often produces significant bottlenecks in funding flows, preventing funds from reaching schools themselves. He also cited a survey, the Hungama Survey Report by the Naandi Foundation, which found that although Anganwadi centers were widespread, they were not always efficient.2 On the day of the survey, for example, only 50 percent of the centers examined provided food, and only 19 percent provided nutrition and education services for mothers. He cited a similar example in which, following a scale up of sanitation

______________

2 For more information about the Hungama Survey Report, please visit http://www.hungamaforchange.org/index.html (accessed October 20, 2014).

infrastructure provision, there was no increase in toilet usage. It is not enough, he noted, to simply provide services—campaigns to raise awareness and generate behavior change are also necessary. In this regard, Bose underscored the role that various stakeholders play and the coordination required to ensure success.

FINANCING IN THE CONTEXT OF CHILD RIGHTS3

Enakshi Ganguly of the HAQ: Centre for Child Rights in India noted that budget analysis plays a crucial role in monitoring state performance and ensuring government transparency and accountability. In budgeting for children’s rights, she suggested that budgeting be based on the following principles: nondiscrimination, indivisibility of rights, and best interests of the child. In financing child programs, she asked, are these principles being upheld?

Ganguly reiterated that the population in India ages 0 to 6 consists of 158 million children, many of whom lack social protection and food security. In this context of vulnerability, she finds that despite some commitments to children as a group and to the young child in particular, there are still gaps. For example, the right to education as dictated by the courts only covers children ages 6 to 14, neglecting the 0 to 6 population. In addition, despite laws that have provisions for a number of services for children, including daycare facilities, for example, the services are not always funded. In response to the growing demand for a separate law for early childhood care in India, Ganguly raised a number of questions regarding the reality of creating new laws and policies: Whose concern is the young child? Do different categories of children require separate laws? Should the rights of children be mainstreamed? What does it mean to create a law, in terms of financing?

Ganguly pointed out that, within India, programs for young children are spread across multiple government ministries and departments. Given that children have a multitude of needs, this is somewhat understandable, she stated, but it makes budgeting and budget analysis difficult. This also means that, practically speaking, except for one program, all others are under the Ministry of Women and Child Development. This ministry is also responsible for drafting and implementing the National Policy for Early Childhood Care and Education, although it has little experience in education, and there is a separate ministry responsible for education, said Ganguly. This point was further highlighted in her response to a question about how to better locate services and provide coordination. She noted

______________

3 This section summarizes information presented by Enakshi Ganguly, HAQ: Centre for Child Rights.

that, because the right to education specifically includes ages 6 to 14, those under age 6 are not covered by the Ministry of Education at all. Ganguly pointed out that while it makes certain sense to separate children into age groups to ensure age-specific interventions, it is also important to make the cross-cutting connections among age, category of children, and the issues that confront them. At the same time, it is also important to make these interventions in the context of the continuum of childhood, as each stage impacts the next. When asked about the creation of a common institutional platform, however—a body that integrates programming across multiple departments and ministries such as health, labor, education, and women and child development—she cautioned on its use. For her, specific ministries and departments exist to ensure services for all populations. One overarching platform may become too cumbersome to cover all groups and might lead to the exclusion of some marginalized populations who require extra services or funding. Furthermore, she emphasized that the method of delivery is not the outcome of interest, but rather the development of the child, which might in some circumstances be better served with segmented programming.

Ganguly discussed an array of programs in India dedicated to the young child that are provided by various agencies and ministries for children ages 0 to 6. On the basis of a computation of the allocations made by the government, HAQ: Centre for Child Rights found that their share is 1.16 percent of the national budget for India.4 This does not include the allocations made in the states. Furthermore, she found that funding was not uniformly applied across groups, often leaving out the most marginalized groups, such as social and ethnic minorities and children with disabilities. In particular, she observed an urban/rural divide in the ICDS, which, as previously stated, offers services through Anganwadi centers. Ganguly stated that while children in rural areas receive more services from Anganwadi centers than children in urban areas, rural centers are underperforming, and in urban areas, they are nothing more than feeding centers.

An additional challenge Ganguly highlighted in financing in the context of child rights is that the private sector, both organized and unorganized, is perhaps the second-largest service provider of early childhood education and development. According to her, the quality of service this sector provides is varied and is largely exclusive and expensive, thus inaccessible to those who need it the most. In addition, there is no estimate of the number of children it caters to and the financial resources spent by families. Ganguly added that there is an increasing push for privati-

______________

4 This figure was calculated by comparing the federal budget for India from 2008–2009 to 2013–2014 to the budgets of all programs impacting the young child.

zation of programming for the young child but that the government is ultimately responsible for providing these services. According to her, the state’s responsibility was recognized and clearly articulated in General Comment No. 7—Implementing Child Rights in Early Childhood—in the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child.5 Therefore, she said, the entry of the private sector into basic services, on its own and in public–private partnerships, must not lead to the state’s abdication of its responsibility. Instead, it should contribute to the pool of resources available to the government to be used to augment its own resources. Finally, Ganguly stated the need to harmonize the activities of private service providers with program mandates, standards, and legislation, the primary responsibility for which lies with the government.

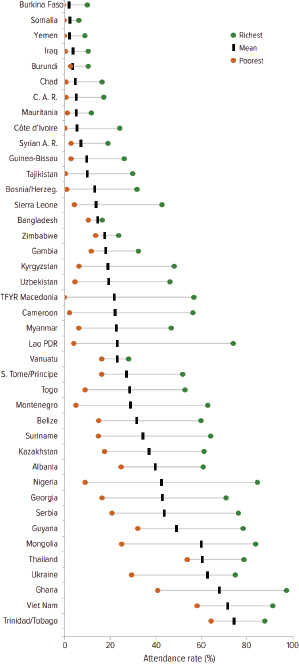

Caroline Arnold of the Aga Khan Foundation (AKF) discussed the state of financing for early childhood education across the globe. While acknowledging progress made in India and other countries, she highlighted the reality of gaps in funding in many countries. In looking at trends in access to early childhood education, she indicated that although gross enrollment ratios have increased in all regions, enrollment is still quite low in several others (as presented by Arnold, 2014). For example, enrollment in preprimary education is high in Latin American countries and the Caribbean, as well as in central and eastern Europe, but it is very low in South Asia, the Arab states, and sub-Saharan Africa. Arnold also highlighted gaps in education among children within countries. In preprimary schools in Tajikistan, for example, enrollment is 4 times higher for urban children than rural children and 20 times higher for rich children than poor children (as presented by Arnold, 2014). Figure 3-1 shows the discrepancy in enrollment status by income within countries. Arnold argued that these gaps show a lack of financing for early childhood education and that political will for investments is necessary to create equity.

AKF works in several countries to address these gaps and mobilize public financing for early childhood education. Arnold shared a few examples from AKF’s work in Central Asia. In several countries in this region, school classrooms go underutilized. AKF has worked with governments to initiate preprimary classes in these empty spaces, with teachers being paid by the community. The ministries of education have committed to taking on these salaries as the program scales nationally. In Tajikistan, for

______________

5 For more information on General Comment No. 7, see http://www2.ohchr.org/english/bodies/crc/docs/AdvanceVersions/GeneralComment7Rev1.pdf (accessed October 5, 2014).

6 This section summarizes information presented by Caroline Arnold, Aga Khan Foundation.

FIGURE 3-1 Disparities between rich and poor in access to preprimary education (percent of children aged 36 to 59 months attending some form of organized early childhood education program, by wealth).

NOTE: Created using information contained in the World Inequality Database on Education.

SOURCE: Arnold, 2014.

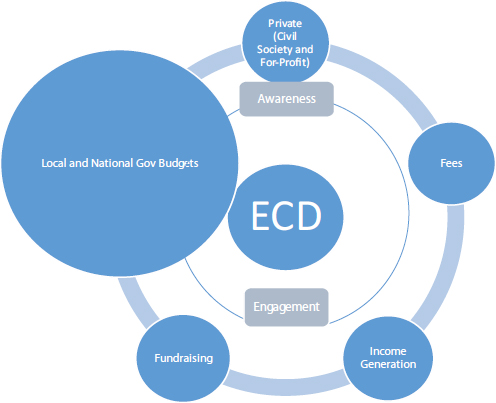

example, the commitment to absorb costs has been made, and in Kyrgyzstan, the government has almost wholly done so in terms of both salaries and operations, according to Arnold. She stated that in Afghanistan, the program is still a decade away from government uptake. In these countries, where public financing is still in its infancy, Arnold said there is a role to be played by the community in terms of assessing fees, fundraising, and generating income for schools, even while public financing remains the biggest piece of the puzzle (see Figure 3-2). The financial investment from the community builds local ownership of financing.

When some workshop participants questioned a fee-for-service structure of early childhood education, Arnold argued that free education is a worthwhile goal but not necessarily achievable in the short term. She asserted that the key element was ensuring that the ability to pay was not a factor in access and that some provision must exist to include children from families who could not afford to pay. While the goal is to have gov-

FIGURE 3-2 Elements of the financing puzzle.

NOTE: ECD = early childhood development.

SOURCE: Arnold, 2014.

ernments absorb costs, having parents contribute even a small amount lends itself to sustainability, Arnold stated.

She also emphasized the role of local engagement not only in financing but also in providing a rationale for such financing. In the countries in which AKF works, she noted that having local evidence for the cost-saving benefit of early childhood education programs has had a significant influence on policy makers prioritizing scarce resources. Arnold closed her talk by referencing a new program of AKF in which an investment vehicle is created to invest in businesses, with a portion of the financial returns going into a nonprofit trust mechanism to fund social development. Although the program is still in early stages, Arnold noted that it held promise for innovating financing schemes for social impact in underresourced locations.

FINANCING SERVICES FOR CHILDREN WITH DISABILITIES: SHISHU BIKASH KENDRA CHILD DEVELOPMENT CENTERS OF BANGLADESH7

Ashrafi Ahmad of the Directorate General of Health Services spoke about the rising rates of neurodevelopmental disorders in Bangladesh. From 1990 to 2013, she said, the rate of under-5 infant mortality has declined steadily (UNICEF et al., 2014). Neurodevelopmental disorders, however, have risen in almost inverse proportion, from 68 per 1,000 in 1988 (Zaman, 1990) to 185 per 1,000 in 2013 (GOB Survey, 2013). To combat this issue, Ahmad said, the government of Bangladesh has incorporated into its Hospital Management Plan the establishment of Shishu Bikash Kendras (SBKs), or child development centers, located within medical college hospitals throughout the country. According to Ahmad, SBKs are comprised of child physicians, child psychologists, and developmental therapists whose collective aim is to prevent disability in children, optimize their development, and improve their quality of life. These objectives, she said, are achieved through providing cost-free early screenings, assessments, interventions, early treatment, and management of developmental delays and disabilities. To date, 15 centers have been established, with an additional 5 planned per year. As of June 2014, 110,000 children have been screened, some of whom were referred from other wards in the hospitals. Ahmad indicated that SBKs have been successful in the early detection of neurodevelopmental disorders.

Ahmad noted that SBKs fall under the government of Bangladesh’s operating budgeting and are funded by a donor pool fund. She added that

______________

7 This section summarizes information presented by Ashrafi Ahmad, Hospital Management Services, Directorate General of Health Services.

some challenges are found in the system, particularly in funding flows. For example, she explained that donors contribute their funds to a pool, which is held in the operating portion of the government’s budget. The program operates per its own budget, and funds are then requested from the donor pool for reimbursement. However, she said, the request goes through numerous layers of bureaucracy in the central government, such that reimbursement requests (which are used to pay salaries, for example) often take months to be processed. To address these lags, Ahmad said, additional direct funding is being sought from potential donors to whom the program would be directly accountable.

This page intentionally left blank.