6

Cash Transfers and Affordability

In a panel on cash transfers and affordability, speakers offered information on opportunities and challenges presented by the use of demand-side interventions. Cash transfers, which can be implemented in various ways, generally serve the purpose of bridging gaps in income or fee-for-service programs. They can be conditional, based on a set of requirements to receive the money or on how it can be spent, or unconditional, without any stipulations. Both approaches have shown evidence of success in various contexts. Speakers discussed the role cash transfers play in improving access to services, as well as their limitations. They also examined cash transfers in the larger context of additional inputs for systems improvements.

Quentin Wodon of the World Bank introduced the session on cash transfers and affordability with some reflection on the value parents place on early childhood development. He provided qualitative evidence that most parents know the value of investing in their young children and are willing to invest but that they often cannot do so because the cost of services is too high. Work on Uganda, for example, shows that while the country has implemented free universal primary and lower secondary education, preprimary education is provided mostly by private organi-

______________

1 This section summarizes information presented by Quentin Wodon, the World Bank.

zations, and the cost of attendance is often high. Even when fees may be lower, they are not always affordable for the poor (Tsimpo and Wodon, 2015).

For low-income families, both conditional and unconditional cash transfers have proved useful in some circumstances. They are generally well designed, but not necessarily a panacea. Wodon cautioned that, where possible, it may be better to simply provide key services for free. He gave the example of Burundi, which saw a 20 percent increase in enrollment when the government made public primary schools free (Sommeiller and Wodon, 2015). At the same time, however, Wodon noted that good quality matters to increase take-up of services, as again evidenced in Uganda. When birth delivery services were provided for free, some women still did not use the services provided by health facilities in part because of quality issues both in terms of personnel and infrastructure (Tsimpo and Wodon, 2015).

Wodon also mentioned the successful experience of Muso in Mali, which has succeeded, at low cost, in reducing child mortality by a factor of 10 thanks to a network of community health workers and free care for families in need. A poster on Muso presented by Naina Wodon (2014) at the workshop summarized results from an evaluation of the impact of the project in its catchment area by Johnson et al. (2013) and provided information on the innovative financing mechanism—part of the topic for this workshop—used to fund the project. Financing for Muso came in part from a global Rotary grant managed by the Rotary Club of Washington, DC, with 24 dozen Rotary Clubs in 11 countries across 4 continents coming together to support the project.

A HUMAN DEVELOPMENT PLATFORM WITH CASH TRANSFERS AND QUALITY SERVICES2

Amarjeet Sinha of the Department of Social Welfare, Government of Bihar emphasized the importance of ensuring quality in services. Although cash transfers increase access, health indicators will not improve unless backed by quality services. He gave the example of Janani Suraksha Yojana, a safe motherhood intervention that aims to reduce maternal and infant mortality by bringing more women to facilities to deliver their babies. The initiative provides financial assistance for this service to women living below the poverty line. Sinha stated that deliveries in facilities did increase—between 55 and 90 percent—but that the quality of services did not change. He also spoke of a program in Bihar in which

______________

2 This section summarizes information presented by Amarjeet Sinha, principal secretary, Department of Social Welfare, Government of Bihar.

girls (and later boys) were given bicycles for enrolling in school when they reached the ninth grade. Bicycles were not only provided as an incentive to increase enrollment but also had the more practical benefit of providing children a means of transport to school and other locations. According to Sinha, therefore, to improve outcomes, there needs to be a focus on the quality and utility of the interventions and services themselves. However, he suggested that cash transfers are difficult to implement in the context of the developing child because children are very resource- and labor-intensive. It is not just about paying for services, but providing the time for parents to interact with their children, as well as meeting children’s health and nutritional needs.

Sinha proposed that a common platform for human development takes a more holistic approach to incorporate such mechanisms as cash transfers to support children and their caregivers. In the state of Bihar, Sinha pointed to a cabinet committee on human development with 16 to 18 indicators on child development, such as education, health, and age at marriage. According to him, this committee—the first of its kind in India—takes a common approach to addressing issues around children, ensuring that their cross-sectoral needs are met but avoiding redundancy in service provision. Sinha recalled that this platform was developed within the context of the MDGs and the question of what each sector’s role should be in achieving the MDGs.

With a shared set of indicators to measure these outcomes, Sinha argued that it is then easier to allocate responsibilities to specific departments. In addition, he said the use of a common platform allows for more intersectoral approaches to financing investments in young children because many outcomes are interrelated. For example, nutritional inadequacy affects learning ability over time. He suggested that a segmented approach might lack the coordination necessary to bring the sectors together but that a common platform could cut through bureaucratic red tape more easily. Although each department has its own budget to implement its programs, Sinha said those programs constitute a larger plan approved at the cabinet level.

Sinha outlined several challenges inherent in public delivery that might be easier to address with greater cohesion in the government. For example, he noted that food security is an issue in which cash transfers can be useful, but only insofar as there is actual supply of these goods. Nowhere in the world, he postulated, has human development happened without credible and functional public systems.

In response to a question about ensuring access for disabled or “differently abled” children, Sinha noted that identifying such children has been a challenge because they are not always picked up in a census. He also noted that often the solution is to increase the number of teachers

CASH TRANSFERS, SOCIAL CARE, AND HIV PREVENTION3

Lucie Cluver of Oxford University shared a set of findings on the impact of cash transfers on HIV risk behavior. Using propensity school matching4 to simulate a randomized control trial, her team compared 6,000 adolescents whose families received a small child support grant from the South African government against those who did not (Cluver et al., 2013). They found promising results. For girls whose families received the funds, there was a 50 percent odds reduction in transactional sex5 and a 70 percent odds reduction in the risk of disparate sex.6 Both of these are big risks for girls in sub-Saharan Africa, according to Cluver.

Cluver noted that while there was success with girls, cash transfers did not have an effect on boys’ risk of contracting HIV or behaving in risky sexual ways, such as multiple partners, unprotected sex, and having sex while drunk or taking drugs. In other words, she said, the intervention had little effect on the teenagers’ risky behavior and other behaviors that are not related to having money. It did, however, give girls the ability to make decisions around who their sexual partners would be by reducing the dependence on men who might pay their school fees.

While these results were somewhat successful, Cluver noted that several stakeholders thought there might be a way to introduce an additional component to the program to improve results. What they found most effective was a system of cash plus care with care defined as positive parenting, school counseling, teacher support, or other components as determined at the country level (Cluver et al., 2014). For girls, cash plus care had an additional benefit, but for boys, while cash alone did nothing, cash plus care resulted in a 50 percent odds reduction in HIV risk behavior incidence.

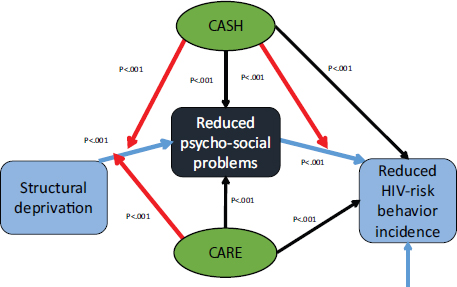

In explaining the mechanism of this successful program, Cluver displayed a model with multiple points of intervention (see Figure 6-1). In the model, structural deprivation, such as living in an AIDS-affected

______________

3 This section summarizes the information presented by Lucie Cluver, Oxford University.

4 Cluver and her team matched participants on numerous characteristics and compared those in the group receiving cash transfers against those in the group who did not receive cash transfers.

5 Sex in exchange for money.

6 Sex with a partner more than 5 years older.

FIGURE 6-1 Cash and care: Greatest effects for highest-risk adolescents.

NOTE: P < .001 indicates high statistical significance.

SOURCE: Cluver et al., 2014.

family, an informal settlement, the context of hunger, or high community violence setting, interacts with mediators of increased psychosocial risk, such as abuse, school dropouts, psychosocial problems, and delinquency, to lead to HIV risk behavior. Cash and care not only directly impact psychosocial risk and HIV risk behavior, but they also have a moderating effect on the pathways between these elements. Because of that latter effect, Cluver indicated the program is most effective with those who are most structurally deprived—in other words, it counters the inequalities with which children start.

Cluver pointed out that cash plus care extended beyond HIV and also had effects in areas such as reduced pregnancy, school dropout rates, and criminal behavior. She also noted strong evidence that the earlier these interventions are implemented, the more impact they will have. Studies conducted in Latin America and South Africa show positive links between early child support grants and parenting programs on HIV risk reduction. But in order to maintain the most success out of a cash plus care program, Cluver stated, it needs to start early and be sustained throughout childhood. However, she acknowledged that the research is still in early stages, and more knowledge is needed. In addition, Cluver said that more analysis is needed on the cost of the intervention to determine the best way to fund it.

This page intentionally left blank.