Building healthier and more resilient and sustainable post-disaster communities is a multifaceted endeavor that requires complementary investments to address interrelated physical, social, and economic environments, not single-purpose projects. Recovery entails a multistage process of applying a set of resources, both financial and human capital, first to restore a community’s infrastructure, services, economy, and health and then, where possible, to improve them beyond pre-disaster levels. No single program can meet the complex and diverse recovery needs of a community.

The process of assembling the resources required after a disaster has been likened to the creation of a patchwork quilt: community leaders represent the quilters, who must catalyze the development and realization of a new vision; the pattern for the quilt, representing the recovery plan, is informed by information from existing plans, data repositories, and experts who can provide technical assistance; and the material for the quilt comes from an array of programs providing funding and/or services to realize the vision (Thomas et al., 2011). The quilt is created through the concerted efforts of the whole community—government and the nonprofit and private sectors—all working to stitch the many pieces together. This chapter describes this process to facilitate the participation of the many audiences for this report (as detailed in Chapter 1) in the planning for and realization of a vision for a healthier post-disaster community. Included are summaries and analyses of key funding sources that can be applied to minimizing the impacts of a disaster on health and social services and ultimately creating healthier communities.

RESOURCE IMPLICATIONS OF DISASTER DECLARATIONS

The resources that become available after a disaster will depend on the pattern and extent of damage and whether the crisis results in a presidential declaration of a major disaster, which triggers significant federal assistance. Regardless of whether there is a presidential declaration, however, recovery must occur, and the mobilization of resources from all sources represents an opportunity to create a healthier community.

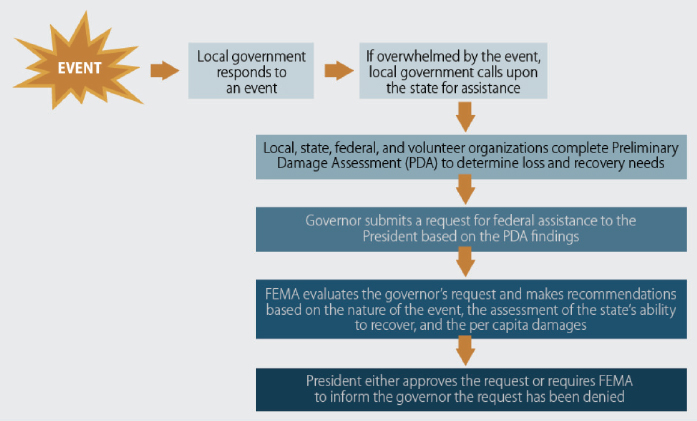

After a disaster, local officials conduct a visual assessment of the damage and share that information with the state, which then decides whether a state disaster declaration is needed. If it is determined that the damages exceed the state’s ability to respond, the governor’s office can request, through the regional Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) office, that the President make a federal disaster declaration (CRS, 2014a; Smith, 2011). FEMA then conducts its own damage assessment and compares

FIGURE 4-1 The Stafford Act process for declaring a major disaster.

SOURCE: CRS, 2014b.

estimated monetary losses with a predetermined per capita threshold. This information is presented to the President along with a recommendation, but ultimately the President decides whether to declare a major disaster (see Figure 4-1). A major disaster is declared when there is a clear need for the President to provide federal disaster assistance under the auspices of the Robert T. Stafford Disaster Relief and Emergency Assistance Act1 (Stafford Act), which is the traditional federal vehicle through which post-disaster assistance is delivered (CRS, 2014b).

Although funding receives the greatest attention in discussions of disaster assistance resources, Smith (2011) delineates three major resource categories: financial resources, policy, and technical assistance. While there is no question that financial resources are requisite to community recovery efforts, greater attention to the other categories is warranted so that communities understand the full spectrum of assistance that is available. Often, policies and technical assistance will be tied to individual funding programs.

Policy may not commonly be viewed as a resource but can have a major influence on recovery processes and outcomes. Policies can create incentives (or remove disincentives) for rebuilding in smarter, more resilient ways. For example, the Sandy Recovery Improvement Act2 removed the penalty associated with structural or functional changes made to infrastructure when rebuilding using FEMA Public Assistance funds (described further below).

________________

1 42 U.S.C. § 5121 et seq.

2 Sandy Recovery Improvement Act of 2013, Public Law 113-2, 113th Cong., H.R.152 (January 29, 2014).

Technical assistance can encompass education, training, and outreach efforts (Smith, 2011), and it is an important means of sharing knowledge on both lessons learned from previous disasters and resources available to support recovery. It helps build local capacity and expertise and strengthen relationships at the local level so that communities are better able to manage on their own when future disasters fail to elicit a major disaster declaration. The capacity for technical assistance is enabled by assessment processes designed to expand the evidence base for decision making. The practice of conducting after-action evaluations (or hotwashes), for example, has yielded information on best or promising practices, as well as lessons about what has not worked in previous disaster experiences. In some cases, this information is distilled into guidance materials. Examples of databases created to serve as clearinghouses for this information include FEMA’s Lessons Learned Information Sharing system and, specific to health information, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ (HHS’s) Disaster Information Management Research Center (http://disasterinfo.nlm.nih.gov). In most cases, these evaluations have been oriented to the disaster response phase, but the information they yield may also be relevant to short-term recovery and may provide valuable methodology or examples.

FEDERAL RECOVERY PROGRAMS AND THEIR APPLICATIONS TO HEALTH RECOVERY

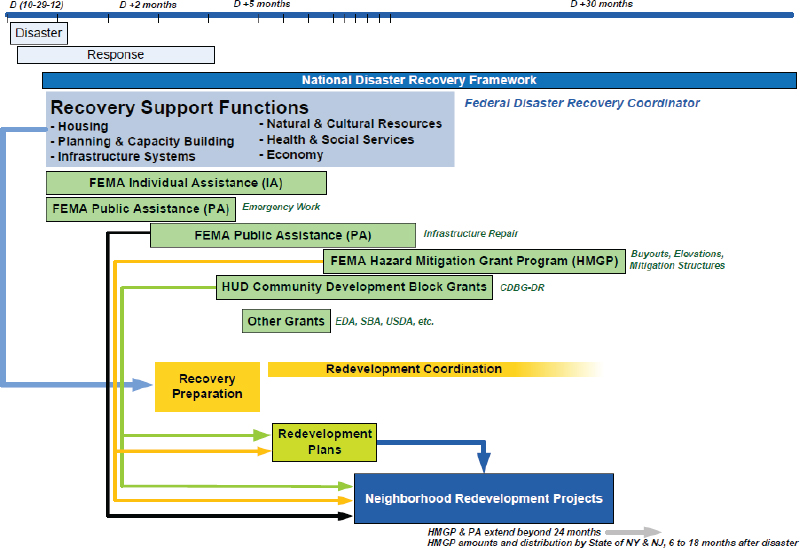

If the President declares a major disaster, a joint field office is established, a federal coordinating officer is named, and an array of federal programs are activated to assist in the response and recovery effort (see Figure 4-2 for a funding timeline and Annex 4-1 at the end of this chapter for a summary of programs). In a major disaster, a federal disaster recovery coordinator also is named, along with a state counterpart. The joint field office includes state partners, including a state coordinating officer, and comprises personnel from federal and state agencies. Staff are organized according to Emergency Support Functions (ESFs) and Recovery Support Functions (RSFs) (described in Chapter 3). Operation plans and project specifications are developed and administered in this office, in some cases supplemented by area field offices in other parts of the state. In coordination with state agencies and the state coordinating officer, federal resources—a combination of grants, loans, and technical assistance—can be used for:

- post-disaster recovery planning,

- debris removal,

- infrastructure repairs,

- financial support to individuals and families,

- services such as crisis counseling and case management,

- economic development, and

- hazard mitigation.

FEMA Funding Programs Authorized Under the Stafford Act

FEMA programs authorized under the Stafford Act include Individual Assistance, the Crisis Counseling Assistance and Training Program, Public Assistance, and the Hazard Mitigation Grant Program, as described briefly below. (For more information on disaster relief funds, see the resource lists in Appendix C.) Not all programs authorized by the Stafford Act are activated after a major disaster. Individual Assistance but not Public Assistance may be offered after some disasters, and vice versa. Damage assessment information, along with other relevant information on need, is used in determining which programs will be activated. In most cases, however, hazard mitigation funds will be offered (FEMA, 2014a).

Individual Assistance comprises a collection of programs designed to provide individuals and families with aid including but not limited to temporary housing, living expenses, limited home repairs (if not covered by insurance), unemployment assistance, legal services, and medical expenses not covered by insurance (CRS, 2012a). For most of these forms of assistance, individuals apply directly to FEMA. Individual Assistance programs support health recovery by providing survivors with financial assistance for

FIGURE 4-2 Recovery planning timeline.

NOTE: The diagram is derived from a combination of various Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) and the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development’s (HUD’s) graphics, based specifically on the post-Sandy recovery initiatives in the state of New York but generalized for all disasters where an element of Community Development Block Grant-Disaster Recovery (CDBG-DR) funding is included. The diagram is not expected to replace the specialized program guidance for funding sources such as FEMA or HUD, rather to illustrate the interrelatedness when viewed from a state or community perspective.

SOURCE: B. Hokanson/PLN Associates.

essential goods (e.g., food), services (e.g., medical services), and shelter (through repair funds or provision for temporary housing costs) during the short-term recovery period (individual and household assistance generally is limited to a period of 18 months).

The Crisis Counseling Assistance and Training Program (CCP) is the largest single federal program supporting disaster-related behavioral health services. The U.S. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) operates the CCP with funds provided by FEMA. Authorized under the Stafford Act, CCP grants are available only after a presidential disaster declaration but are not automatic; the affected state must formally apply for CCP funding. The grants are of two types: the Immediate Services Program, with a duration of 60 days, and the Regular Services Program, which lasts 9 months. The main goals of the CCP are to contact a large number of people by face-to-face outreach, to offer basic crisis counseling and connection to community support systems, and to make referrals to traditional mental health services when necessary. The funds cannot be used for formal behavioral health diagnostic and treatment services. The types of services funded by the CCP are individual and group crisis counseling; supportive educational contact; assessment, referral, and resource linkage; and media and public service announcements. These services typically are provided by behavioral health organizations under contract to the state mental health authority (SAMHSA, 2009). The providers of these services are a combination of mental health professionals and paraprofessionals trained in crisis counseling. Training and education of CCP staff also can be undertaken with grant funds. The CCP, as well as challenges related to the program’s current design, are discussed further in Chapter 7.

Public Assistance3 grants generally represent the largest disbursement of federal funds for short- and long-term disaster recovery. They are the primary form of assistance offered by FEMA to state and local governments for debris removal and for the repair, replacement, or restoration of public infrastructure (e.g., roads and bridges, public buildings), including many that support health and safety (police and fire stations, hospitals, schools) and restore the fabric of the community (e.g., libraries, community centers, schools).4 Certain nonprofit organizations (e.g., hospitals) also are eligible for these grants, but for-profit businesses are not. FEMA obligates funds for Public Assistance projects based on detailed cost estimates derived from damage assessments. There is usually a 25 percent state cost share (FEMA provides 75 percent of estimated costs and states must cover the other 25 percent). However, the President can partially or totally waive these costs to the state, or they can be covered with funds from other federal grant programs, such as the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development’s (HUD’s) Community Development Block Grant for Disaster Recovery (CDBG-DR), which is discussed in more detail below.

Although Public Assistance funds generally have been used to restore facilities to their pre-disaster state and function, hazard mitigation add-on funding (designated as Public Assistance 406 program funds) can be obtained for improvements that strengthen the facility to better resist future hazardous events. Typically, the technical and engineering work of writing specifications and producing cost estimates for repair projects, including additional 406 mitigation, is performed by FEMA personnel or FEMA contractors, subject to approval by the subrecipient and the state. However, 406 proposals must show that the proposed improvements are cost-effective through a cost-benefit analysis. The committee heard testimony that the time requirement for collecting these data and conducting the required analyses can deter making improvements for hazard mitigation purposes during the repair of critical infrastructure, which local governments are under great pressure to restore quickly. It is unclear whether this assertion reflects insuf-

________________

3 This section draws on a paper commissioned by the Committee on Post-Disaster Recovery of a Community’s Public Health, Medical, and Social Services on “Disaster Recovery Funding: Achieving a Resilient Future?” by Gavin Smith (see Appendix B).

4 In the event of a pandemic such as influenza, FEMA may offer direct federal assistance through Public Assistance grants under the Stafford Act if there is a presidential declaration. Such assistance may include, among other things, the provision of emergency medical care and temporary medical facilities; the purchase and distribution of food, water, medicine, and other supplies; management, control, and reduction of immediate threats to public health and safety; and the provision of congregate shelters, mass mortuary services, and security and fencing. However, assistance provided by FEMA may not duplicate assistance provided by HHS or any other federal agency (FEMA, 2009).

ficient surge staffing or other organizational impediments. All costs of project design and development are eligible expenses under the FEMA programs.

Public Assistance funds have historically been among the most restrictive funding sources for recovery because the projects funded under this program generally were limited to restoring pre-disaster conditions (function and structure), with the exception of upgrades to comply with contemporary and applicable codes and standards. Changes to the function or location of facilities can be supported with Public Assistance funds, but in the past, this would result in a reduction in the grant amount (i.e., a penalty). Changes to the Stafford Act brought about by the Sandy Recovery Improvement Act of 2013 not only have streamlined the application processes for Public Assistance funds but also have eliminated disincentives and provided increased flexibility (FEMA, 2013a), thus increasing this program’s applicability to the process of creating a healthier and more resilient and sustainable post-disaster communities. For example, the addition of bicycle lanes during the repair of streets previously would have been penalized by a reduction of the costs eligible for coverage, but under alternative procedures authorized by the Sandy Recovery Improvement Act, this penalty has been eliminated. In planning for the use of Public Assistance funds, communities need to be aware of these important changes.

Hazard Mitigation Grant Program funds are used for mitigation activities during recovery designed to reduce impacts and losses associated with future disasters. For example, these funds can be used for elevations and bulkheads (e.g., sea walls) to protect structures in hazard zones or for buyouts to relocate structures out of hazardous areas. In contrast with the Public Assistance 406 program for hazard mitigation discussed above, FEMA does not approve the use of Hazard Mitigation Grant Program funds for individual projects; instead, distribution of these funds to states is formula based (generally 15 percent of estimated aggregate amounts of Stafford Act disaster assistance5), and states have wide latitude to determine how the funds will be allocated. Hazard mitigation activities can contribute to healthy, resilient, sustainable communities by reducing the risk of future injury and the significant psychosocial impacts associated with disaster-related losses. These activities are discussed further in Chapter 9 (see Recommendation 11).

One other important FEMA program that provides relief after a disaster is the National Flood Insurance Program. Property owners who have purchased flood insurance through this program can submit claims for flood-damaged properties. Most private insurance does not cover flooding, which has been a large problem for community recovery after a flooding event.

Federal Block Grant Programs for Disaster Recovery

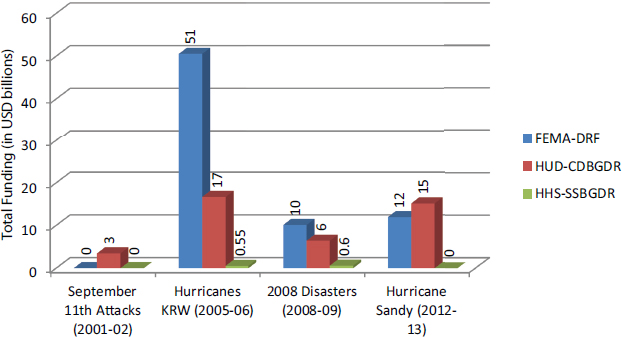

The Stafford Act is the primary means by which federal assistance is provided for recovery, but in the case of a catastrophic disaster, Congress may deem it necessary to provide additional assistance in the form of a supplemental appropriation. In recent decades, two notable grant programs have been used as a vehicle for these supplemental funds: HUD’s CDBG-DR program and HHS’s Social Services Block Grant (SSBG) program. After Hurricane Sandy, CDBG-DR appropriations exceeded levels of FEMA disaster relief funds (see Figure 4-3).

Community Development Block Grant6

Among the largest single sources of supplemental recovery assistance is CDBG-DR. All 50 states and most large cities and counties currently receive an annual appropriation through HUD’s CDBG program for such day-to-day activities as funding community centers and fixing roads. After a major disaster, Congress may choose to use this funding mechanism to provide additional support to communities for

________________

5 To incentivize hazard mitigation planning, states with enhanced mitigation plans are eligible to receive 20 percent of estimated disaster assistance disbursements under the Hazard Mitigation Grant Program.

6 This section draws on a paper commissioned by the Committee on Post-Disaster Recovery of a Community’s Public Health, Medical, and Social Services on “Disaster Recovery Funding: Achieving a Resilient Future?” by Gavin Smith (see Appendix B).

NOTES: FEMA-DRF = FEMA Disaster Relief Funds, including Individual Assistance, Public Assistance, and Hazard Mitigation Grant Program funds; HHS-SSBGDR = HHS Social Services Block Grant Disaster Recovery Funds; HUD-CDBGDR = HUD Community Development Block Grant Disaster Recovery funds; KRW = Hurricanes Katrina, Rita, and Wilma.

SOURCES: Data from CRS, 2012b, 2014b; HUD, 2014a

disaster recovery. CDBG-DR funds are targeted to those communities that have demonstrated significant unmet needs not addressed by other grant programs. These funds have three important advantages over Stafford Act funds: flexibility (owing to their nature as a block grant), the ability to address unmet needs, and targeted assistance provided to socially vulnerable populations. At least half of CDBG-DR funds must be used to assist low- and moderate-income people (unless a waiver is granted by the HUD Secretary). The funds can be used for a variety of disaster recovery activities, including

- the acquisition and relocation of flood-damaged housing as a hazard mitigation activity;

- relocation payments for people and businesses displaced by a disaster;

- debris removal not covered by FEMA;

- rehabilitation of homes and buildings damaged by a disaster;

- buying, constructing, or rehabilitating public facilities such as streets and community centers and water, sewer, and drainage systems;

- code enforcement;

- homeownership needs such as down payment assistance, interest rate subsidies, and loan guarantees;

- public services;

- workforce training and development;

- help for businesses in retaining or creating jobs in disaster-impacted areas; and

- recovery planning and administration costs (HUD, 2014b).

Because they are more flexible and available for a broad range of uses, CDBG-DR appropriations create a number of opportunities for communities to make changes to physical and social environments that influence health. “With community development dollars you can address housing, economic recovery

as well as social services, bricks and mortar, economic development” (Smith Parker, 2014)—all factors that significantly influence health. All that is needed is vision to utilize the funds in creative ways that meet multiple needs (e.g., multipurpose buildings). However, these funds can be used only for needs that arose as a direct result of a disaster. This restriction can be a challenge for some communities, particularly with regard to health and social service investments, as it can be difficult to demonstrate how a disaster exacerbated homelessness or concerns regarding air pollutants that affect health. Furthermore, given their supplemental nature, CDBG-DR funds are not available in all presidentially declared disasters.

The committee heard about several examples of the use of CDBG-DR funds for health-related purposes. After Hurricane Sandy, New York City invested $183 million CDBG-DR dollars in the restoration of Bellevue and Coney Island Hospitals, along with associated personnel and mobile health service costs. As a result of the lessons learned from Hurricane Katrina, Louisiana invested in the creation of urgent care centers in proximity to other health services (Smith Parker, 2014). (The redesign of the health care delivery system in New Orleans during the recovery from Hurricane Katrina is further discussed in Chapter 6 [see Box 6-7].) While these health care system–focused investments are important to healthy communities, perhaps of even greater importance is the opportunity to use CDBG-DR funds to help communities address some of the upstream or social determinants of health that are often exacerbated after a disaster. For example, these funds can be used for workforce development for residents of disaster-impacted neighborhoods. In Springfield, Massachusetts, CDBG-DR funds were used to finance job training programs for community members from underserved neighborhoods in which the population, which already faced multiple barriers to employment before a tornado struck the town in 2011, was also heavily impacted by the disaster (Leydon, 2014).

HUD has used the CDBG-DR funds to advance a forward-looking agenda that promotes resilience and sustainability (specifically promoting consideration of the six livability principles of the Partnership for Sustainable Communities during rebuilding; see Box 2-5 in Chapter 2). As discussed in Chapter 2, the focus of this agenda will yield co-benefits to health, and from a programmatic standpoint, it may be precedent setting. For example, the most recent CDBG-DR funds for Hurricane Sandy relief included a requirement for grantees to (1) show “sound, sustainable long-term recovery planning informed by a post-disaster evaluation of hazard risk,” and (2) “use green rebuilding standards for replacement and new construction of residential housing.”

Social Services Block Grant

SSBGs are administered by the Administration for Children and Families (ACF) within HHS (ACF, 2014b). All 50 states, the District of Columbia, and five territories receive these grants (ACF, 2012), which are designed to help states provide residents with “locally relevant social services,” such as helping people achieve economic self-support and self-sufficiency to reduce dependence on social services and reducing neglect, abuse, and exploitation of children and adults (ACF, 2013a, 2014b). The money is distributed directly to the states, which then determine what services will be provided and to whom and how the funds will be divided among those services (ACF, 2014c).

Supplemental appropriations through the SSBG program are intended to help meet social service needs linked to a disaster, including social, health, and mental health services for individuals. The funds can be used for

- food cards (ACF, 2013b);

- child care vouchers (ACF, 2013b);

- reimbursement to community agencies that incurred costs in providing services to affected people (ACF, 2013b);

- temporary housing (ACF, 2013b);

- education and training to meet the social service needs of affected people (ACF, 2014a); and

- medication and medical equipment (ACF, 2013b).

The block grant also covers the repair and rebuilding of health care, mental health, child care and other social service facilities, as well as vans or other equipment needed to provide social services. However, the committee heard that SSBG funds are oriented more to supporting individual needs than to addressing social determinants of health at the population level (Nolen, 2014).

Leveraging Block Grant Programs

Regardless of whether a supplemental appropriation is made to provide additional funds beyond those authorized under the Stafford Act, the funds available through annual block grant programs such as CDBG and SSBG generally can be reprogrammed for disaster recovery purposes and used for many of the same functions described above for disaster recovery funds.7 Because every state and most large cities and counties receive annual funding through the CDBG program for day-to-day purposes, there is broad familiarity with the requirements attached to these federal funds (CRS, 2011). Leveraging this knowledge after a disaster necessitates ensuring that those familiar with these programs are engaged in the recovery planning process. Community development programs in cities and counties are long-term initiatives that address widespread disparities and are connected with diverse organizations concerned about these issues, including advisory committees and community development financial institutions. These organizational resources are key to planning for effective and optimized disaster recovery. Recovery and community development are overlapping initiatives with virtually identical objectives and tools; thus, integrated approaches are essential.

Other Federal Recovery Funding Programs

In addition to FEMA, a number of other federal agencies may offer disaster recovery assistance through a variety of programs:

- Individuals may apply for loans from the Small Business Administration (SBA) that can be used to replace personal property (e.g., furniture) and to restore a creditworthy homeowner’s primary residence to its pre-disaster state when the damage is not covered by insurance (the loan can be increased to cover additional costs for hazard mitigation). Similarly, businesses can apply for SBA loans to help cover physical damage and losses, as well as economic losses related to the disaster (CRS, 2012a). SBA loans may be an important source of funding to support recovery for private health care providers who are not eligible for FEMA Public Assistance funds.8 In hazard areas such as flood plains where buyouts are proposed, SBA plays a crucial role in what is called bridge financing—the temporary arrangements made to help homeowners transition from an existing mortgage on a damaged, unlivable house to a replacement home elsewhere, given the approximately 24-month waiting period for buyout real estate transactions.

- The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) offers a number of housing and rural development programs to support recovery, particularly for rural communities. For example, after a tornado destroyed Kiowa County Memorial Hospital as well as much of the rest of the small town of Greensburg, Kansas, USDA funds were used together with FEMA Public Assistance funds and insurance payouts to help cover the costs of rebuilding the hospital.9

________________

7 ACF provides guidance on the use of block grant funds, including CSBGs, SSBGs, and its Child Care and Development Fund, to meet response and recovery needs after a disaster.

8 Federal Housing Administration (FHA)-insured loans from HUD with up to 90 percent loan-to-value ratios also can be used by hospitals (public and private) for reconstruction.

9 E-mail communication, M. Sweet, Kiowa County Memorial Hospital, to R. Kirkland, Institute of Medicine, regarding Institute of Medicine study on post-disaster recovery, September 10, 2014.

- Economic Development Agency10 funds generally are used to support economic recovery. Programming is oriented to job creation or retention projects and initiatives to keep employers from leaving the disaster area. Given the link between economic vitality and the health and wellbeing of a community, these programs are critical to building healthy communities after a disaster.

- The Federal Highway Administration provides emergency relief assistance for repair and restoration of roads and bridges on the federal-aid highway system (nearly all roads and bridges in the United States are eligible) (CRS, 2014a). These funds can be used for improvements that increase the resilience of the infrastructure if the added cost of the betterment project can be justified based on expected future damages from similar disasters (FHWA, 2013).

Further information on the federal and nonfederal funding programs described in this report, and many others, is available through the National Disaster Recovery Program Database, a web-based tool developed by FEMA to support communities in planning for, responding to, and recovering from disasters. This database can be found at https://asd.fema.gov/inter/ndhpd/public/searchHousingProgramForm.htm.

NONFEDERAL RESOURCES FOR RECOVERY

If there is no presidential declaration of a major disaster, none of the funding programs authorized by the Stafford Act are available to support communities through recovery. As a result, there is little in the way of federal support, although, as discussed earlier, existing federal grant funds received by a community can be reprogrammed after a disaster to yield an additional set of resources, and some federal agencies, such as SBA, USDA, and the Federal Highway Administration, can provide programmatic funding for recovery assistance apart from the funding that is authorized under the Stafford Act. This approach builds local capacity but must be supported by clear guidance and strong vertical integration (e.g., good relationships with federal grant staff).11 Generally, however, if there is no presidential disaster declaration, communities must look to nonfederal funding opportunities, including private-sector investments; charity from nonprofit and philanthropic organizations; and state and local insurance, cash reserves, and disaster budgets when available.12 These funding sources, described below, are important contributors to the pool of recovery resources even when a major disaster is declared by the President.

Funds and other forms of assistance (e.g., goods, facilities) from the private sector are an important component of the disaster assistance framework, and the private sector has an inherent interest in seeing a community recover. Thus, one critical application of private recovery funds is the significant investment made by for-profit organizations—which are rarely eligible to receive federal assistance—in rebuilding their own infrastructure and restoring business operations. As noted earlier, the viability of a community is dependent on its economic vitality (e.g., employment opportunities). Therefore, the decision of local businesses to rebuild within the community has major implications for the ultimate success of recovery in terms of community confidence, employment opportunities, and availability of services, all of which will ultimately affect the health and well-being of the local population.

Businesses also frequently donate funds to nonprofits to support community recovery. For example, Nike provided financial support to the nonprofit design group Architecture for Humanity to support

________________

10 The Economic Development Agency is part of the U.S. Department of Commerce.

11 This section draws on a paper commissioned by the Committee on Post-Disaster Recovery of a Community’s Public Health, Medical, and Social Services on “Disaster Recovery Funding: Achieving a Resilient Future?” by Gavin Smith (see Appendix B).

12 Cash reserves and disaster budgets are difficult to ensure in current economic times. Some governments levy a tax on certain services to develop this funding source, while others appropriate amounts from their general funds for a disaster account. However, these funds usually are not at a level that can provide the needed recovery assistance and are designed to supplement the expected federal funds (e.g., for cost shares).

the reconstruction of school athletic facilities in New Jersey after Hurricane Sandy (Open Architecture Network, 2014).

One of the most critical sources of funds for rebuilding after a disaster and for accelerating recovery is private insurance. Many homeowners and businesses hold private insurance policies, and payouts are made according to the terms of the contract. Homeowner’s policies cover not only the dwelling itself but also the owner’s possessions and are usually a condition for obtaining a mortgage. Yet while most homeowner’s policies cover the damage from tornadoes, that from floods and earthquakes often is not covered, creating a gap. Flood coverage is available through a separate policy from the National Flood Insurance Program and from some private insurers. Nonetheless, lack of insurance and underinsurance are a major problem for homeowners and businesses, including critical service providers such as hospitals. Moreover, governments often are self-insured, so any expenditures on disaster recovery must come from their overall budget.

Investment firms and private developers will provide funds and human capital used for infrastructure restoration and neighborhood redevelopment, and thus they have a large role to play in a healthy community approach to recovery. The general category of these activities is termed “community development.” The scope of these activities, however, is larger than direct federal expenditures, and it entails using such mechanisms as tax credits, community loan funds, and community development financial institutions. Community development corporations, which aid low-income communities with capacity building and planning and development, may invest in micro loans, job creation, affordable housing, and other community amenities that may not otherwise be a priority for developers.13 Local initiatives are supported by the Community Development Financial Institutions Fund in the U.S. Department of Treasury and the “advent of a new investment tax credit for small business and community facilities, the so-called New Markets Tax Credit” (Erickson and Andrews, 2011, p. 2058). Some types of development have health and social service improvements as explicit goals (Erickson and Andrews, 2011). One study found measurable health benefits to populations served by transit-oriented development and walkable neighborhoods in Charlotte, North Carolina, where a community development organization (Low Income Investment Fund) “was needed to crack the code in assembling favorable capital so that low-income families could share in the benefits of more walkable neighborhoods that have stronger connections to the regional economy” (Erickson and Andrews, 2011, p. 2060). Disaster recovery efforts can tap these diverse resources. In the case of recovery of Joplin, Missouri, from the 2011 tornado, for example, the Missouri Housing Development Commission redistributed its tax credits such that Joplin received 38 percent ($100 million) of the statewide allocation (Novogradac & Company LLP, 2011).

Nonprofit and Philanthropic Resources

Nongovernmental (community-based, faith-based, and national-level) organizations are at the front line of all disaster response and recovery efforts. They provide an array of short- and long-term assistance to fill gaps left by governmental programs that result in unmet needs, including social services and mental health, and thus are essential to health recovery. They are able to respond quickly with funding after a disaster and allow for more flexibility than governmental funding sources; thus, pre-disaster relationships with these organizations at the local level are essential. The programs offered by these organizations are in many situations the first step for an individual’s or a family’s recovery. Some provide training, and others work directly on restoring the infrastructure of a community, but generally in the realm of assisting in home repairs and/or rebuilding (e.g., Habitat for Humanity), not rebuilding the community’s commercial structures or transportation and utility components. Many of these organizations are members of National Voluntary Organizations Active in Disaster (VOAD). Coordination of their activities at the state and local levels occurs through VOAD and/or local Community Organizations Active in Disaster (COAD) (see

________________

13 This section draws on a paper commissioned by the Committee on Post-Disaster Recovery of a Community’s Public Health, Medical, and Social Services on “Disaster Recovery Funding: Achieving a Resilient Future?” by Gavin Smith (see Appendix B).

BOX 4-1

Voluntary and Community Organizations Active in Disaster

Voluntary Organizations Active in Disaster (VOAD) are community organizations comprising nonprofit and for-profit organizations that work together to prepare for, respond to, recover from, and mitigate disasters. Rather than providing direct services, VOAD provides a network through which individual organizations can help during a disaster in an efficient manner and with reduced duplication of services (Riverside County VOAD, 2011).

National VOAD is an organization of more than 100 nonprofit and faith-based organizations involved in disaster response and recovery nationwide (NVOAD, 2014). Within National VOAD, each organization/ denomination has specialized roles in response and recovery; this system encourages coordinated effort in disasters among members nationwide (VAUMC, 2014).

Community Organizations Active in Disaster (COAD) go by many different names (and are sometimes synonymous with VOAD), but they tend to be local- or regional-level groups that are organized independently but in loose affiliation with state and national VOAD (Missouri SEMA, 2014). COAD works almost exclusively on recovery and can form the core of a long-term recovery group, but there is a growing awareness of the need for their involvement throughout the emergency management cycle. COAD may or may not focus explicitly on health, depending on who is at the table. In Kentucky, for example, the state health department appoints a representative from a county health department to all COAD. COAD emphasizes the building of relationships prior to a disaster, and can facilitate discussion of healthy community goals for recovery.

FEMA’s “whole-community” approach acknowledges the critical role of VOAD and COAD, noting that these types of collaborations can leverage existing assets, ensure that recovery efforts meet the actual needs of the community, and make the community more resilient (FEMA, 2011b).

Box 4-1). VOAD and COAD also are often involved in the formation of long-term recovery committees (LTRCs), which can serve as a neutral conduit for recovery funds donated to assist individuals and families. LTRCs comprise representatives from faith-based communities, nonprofit agencies, charities and foundations, and state and local agencies. They are involved in fundraising, organizing volunteers, and providing assistance to those who have unmet needs even after receiving help from government disaster aid programs. FEMA’s voluntary agency liaisons and National VOAD can assist communities in setting up LTRCs.14

Foundations/philanthropies often become involved in financial assistance during major disasters. Their funds normally are applied to other nonprofit organizations already in the disaster response and recovery arena, or are used specifically to fund LTRCs. As an example of how nonprofit and philanthropic funding can help support improvements in health during recovery, the American Red Cross and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation funded a mental health infrastructure and training project in New Orleans to address gaps in the capacity to deliver mental health support services after Hurricane Katrina (Meyers et al., 2011).

Academic institutions are another kind of nongovernmental organization that can supply a wide range of resources after a disaster to promote a community’s recovery and resilience. Although they are not as likely to be a source of recovery funding as other nongovernmental organizations, these institutions can provide other important resources, such as facilities and training (Dunlop et al., 2014). Yet despite their resources and capacity for community engagement, academic institutions are a source of often untapped potential. Their increased engagement in community recovery may be achieved by establishing formal relationships with emergency management and public health agencies (e.g., contracts, memorandums of understanding, advisory positions) in advance of a disaster (Dunlop et al., 2014).

________________

14 National VOAD has created a manual to support the development of these long-term recovery structures, available at http://www.nvoad.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/long_term_recovery_guide_-_final_2012.pdf (accessed April 4, 2015).

State and Local Government Funding Mechanisms

Some states may create rainy day funds that are specifically for or applicable to a disaster situation. A state-level department will administer the grant, and local governments can apply for these funds after a disaster. “Currently, many state grants offer limited funds with extensive administrative requirements and narrowly defined performance expectations. The outcome is that many grant opportunities are prohibitive and ineffective. Efforts are needed to inform and educate policy-makers about these restrictions which impact the intended use of these funds to best meet local community needs” (GCHD, 2007, p. 5).

Taxes and bonds, which are often used to fund capital improvements outside of the disaster context, are another potential source of funding for state and local governments to assist in recovery when there is no presidential declaration of a major disaster or to cover matches and noneligible expenses (e.g., upgrades) under federal grant programs. Bond initiatives allow state and local governments to borrow from investors, usually within their own jurisdictions, and are appealing as a funding vehicle because they often are exempt from federal and state income taxes. These public-purpose bonds are used to improve and rebuild roads, streets, highways, sidewalks, libraries, and government buildings (DOT, 2012). In Joplin, Missouri, where the 2011 tornado destroyed a number of schools, bond financing ($62 million in general-obligation bonds sold by the city’s school district) was used to cover some of the rebuilding costs (Niquette, 2013).

According to Johnson and Olshansky (2013, p. 18), when large sums of public funding become available after a disaster, “the true power over the recovery resides with the level of government that controls the flow of money and how it is acquired, allocated, disbursed and audited.” In some cases, a newly established recovery office will hold these powers, but in others, existing legislative and administrative units will assume new responsibilities. Adding to the complexity of the recovery process is the fact that different federal recovery assistance funds may be dispersed to states, local governments, or both.16 In the case of Hazard Mitigation Grant Program and Public Assistance funds from FEMA, the state (usually the emergency management agency) will be the grantee. However, eligibility of restoration projects for Public Assistance funds is determined by FEMA, and the state acts as a facilitator, working with local governments and institutions that apply for the funds. In contrast, for the Hazard Mitigation Grant Program, the state emergency management agency grantee will make decisions about how the funds are used. In the case of CDBG-DR funds, states and/or local governments can be the grantees, depending on the extent and pattern of damage after the disaster, and the grant often will be administered by an agency responsible for administering the annual CDBG appropriation (i.e., not the emergency management agency). The level of government receiving the funds will control how they are spent (as long as HUD requirements are met). In some cases, a city and the state in which it is located may both receive CDBG-DR funds (as was the case in New York after Hurricane Sandy). In the case of large disasters when there has been a supplemental appropriation, this complexity poses challenges to the coordination of funding both horizontally and vertically (discussed further below).

State grant recipients of Hazard Mitigation Grant Program and CDBG-DR funds can finance recovery activities directly or pass the funds along to local governments. The process by which states determine the localities to fund and the amount of those awards varies. When serving as “pass-through” organizations, states work with both federal agency representatives and local government officials to evaluate a community’s needs in the aftermath of a disaster and determine whether damages meet eligibility requirements for federal assistance. State grantees (and local grantees in the case of entitlement communities that receive CDBG-DR funds) are responsible for the development of prioritization (HMGP) or action plans (CDBG-DR). In these plans, the grantee determines which types of projects can be funded, working within

________________

15 This section draws on a paper commissioned by the Committee on Post-Disaster Recovery of a Community’s Public Health, Medical, and Social Services on “Disaster Recovery Funding: Achieving a Resilient Future?” by Gavin Smith (see Appendix B).

16 FEMA Individual Assistance and SBA loans go directly to impacted community members and organizations.

federal guidelines such as “cost-effectiveness” in the case of the Hazard Mitigation Grant Program and providing assistance to a set percentage of low-income disaster recipients in the case of HUD’s CDBG-DR.17 State grantees also set criteria for prioritizing projects when the requests submitted by local governments exceed the available balances. For both HMGP and CDBG-DR activities, planning studies are assumed and encouraged by the federal guidelines, and recipients are expected to spend a portion of the grants (e.g., up to 15 percent) on planning.

CHALLENGES IN APPLYING FUNDING TO THE CREATION OF HEALTHY COMMUNITIES

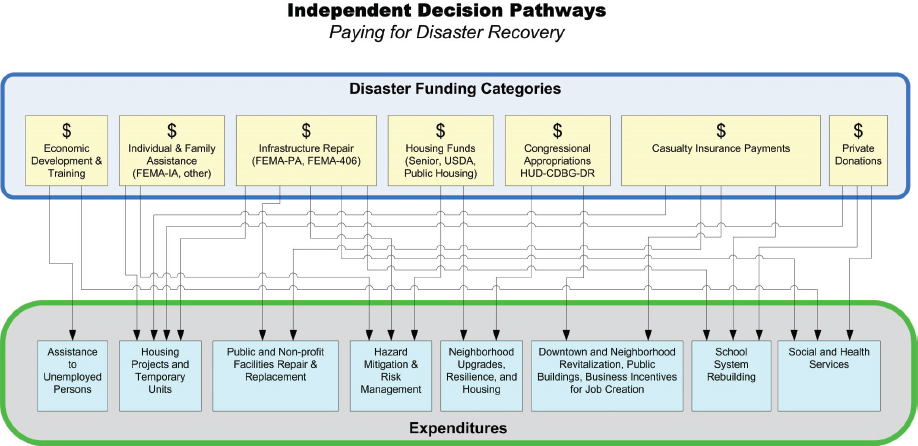

As discussed earlier, a patchwork quilt approach well describes the process of weaving together various funding sources to meet recovery needs. The complexity of this process is illustrated in Figure 4-4.

A number of challenges related to the funding pathways for disaster recovery impede optimal coordination. Foremost among them is the inadequate investment in pre-event recovery planning and capacity building. Post-disaster challenges include the complicated processes by which funds reach localities and the multiple sets of requirements along the way, as well as the variability in timing of assistance. Further, the considerable burden of administering post-disaster federal assistance programs complicates the recovery process and can impede the ability to plan in the aftermath of a disaster (Smith, 2011).

Limited Pre-Disaster Recovery Planning Resources

The National Disaster Recovery Framework (discussed in detail in Chapter 3) promotes pre-disaster recovery planning, including it as a core principle of the framework, but it is not accompanied by any funding to support state and local governments in such efforts (FEMA, 2011a). There are in fact no dedicated financial resources for pre-disaster recovery planning, which is troubling given the evidence that the timing and success of recovery are greatly enhanced by such investments (CPW, 2010; FEMA, 2011a; Smith, 2011). This national lack of investment in pre-disaster recovery planning contributes to an overemphasis on post-disaster assistance, impeding efforts to plan and develop capacity at the state and local levels before an event.18 However, several existing grant programs include recovery as a target capability and therefore can be used to support recovery planning. The Public Health Emergency Preparedness (PHEP) Cooperative Agreement and the Hospital Preparedness Program (HPP) (discussed in more detail in Chapters 5 and 6, respectively) provide funds and guidance for health sector recovery planning activities. Other grant programs that similarly include recovery as a supported planning capability are FEMA’s Emergency Management Preparedness and Homeland Security grants and Pre-Disaster Mitigation grants; the latter provide states and territories with funds for mitigation planning and activities. By law, hazard mitigation plans must be in place prior to a disaster in order for a community to be eligible for post-disaster mitigation funds, thus providing an incentive for pre-event planning.

Although preparedness programs offer communities an opportunity to fund recovery planning efforts, exploiting this opportunity will require many state and local governments to shift priorities. Determination of how the grant funds are to be applied to the different target capabilities is left to the grantees, so the funds have been applied primarily to preparedness activities related to response capabilities (Lockwood, 2014; Pereira, 2013). If funding from the PHEP Cooperative Agreement and HPP continue to decline, as it has over the past decade,19 public health departments will be hard-pressed to maintain current capabilities (CDC, 2011), much less support the development of new ones. There is also significant variability in the proportion of preparedness funds that reaches the local level. As discussed in Chapter 3, an additional

________________

17 HUD monitors periodic program reports from grantees to verify that the required benefit to low-/moderate-income individuals and families is being met (generally required to be 70 percent of total expenditures unless a waiver is granted) (HUD, 2015).

18 This section draws on a paper commissioned by the Committee on Post-Disaster Recovery of a Community’s Public Health, Medical, and Social Services on “Disaster Recovery Funding: Achieving a Resilient Future?” by Gavin Smith (see Appendix B).

19 In 2008, PHEP funds totaled just over $700 million, but in 2013, states and territories received only $584 million. Similarly, HPP funds decreased from nearly $400 million in 2008 to $331 million in 2013 (Pines et al., 2013).

FIGURE 4-4 Funding pathways for disaster recovery.

NOTES: This schematic is not intended to comprehensively describe all disaster assistance categories but shows the complexity of the process by which funds from a multitude of sources are woven together to support comprehensive disaster recovery. This scenario assumes that there has been a presidential declaration of a major disaster and that Congress provided Community Development Block Grant Disaster Recovery funds through a supplemental appropriation.

SOURCE: B. Hokanson/PLN Associates.

challenge related to the use of preparedness funds for recovery planning is the paucity of specific guidance to aid state and local organizations, particularly with respect to long-term recovery.

Challenges in the Post-Disaster Context

Restrictive Requirements That Fail to Align with Community Needs

A common complaint alluded to earlier regarding federal and in some cases state funding programs is their restrictive requirements. Narrowly defined criteria impede the ability of communities to rebuild in ways that improve health and overall system effectiveness. As noted earlier in the discussion of FEMA’s Public Assistance funds, this situation is changed somewhat by the 2013 Sandy Recovery Improvement Act, now Section 428 of the Stafford Act, which removed disincentives that may previously have prevented decision makers from rebuilding infrastructure to any state other than its original form and function.

States can implement further restrictions on federal funding that is passed on to local jurisdictions. When states lack an understanding of local needs, these restrictions may impose an undesirable burden. However, these strictures also can be an opportunity for forward-looking states to promote practices that support increased resilience and sustainability. For example, states may require receiving jurisdictions to adopt higher codes and standards than those currently in place or to develop plans before the release of federal funds20 (Smith et al., 2013).

Coordination Challenges Related to the Timing and Flow of Funding

In the implementation of recovery and reconstruction efforts, local governments frequently face uncertainty regarding when they will receive grant program funding (Smith, 2011). Some programs, such as CDBG-DR and SSBG-DR, require a supplemental appropriation, so the timing of these funds will depend on the speed of congressional action and the time required for federal agencies to implement the legislation. The inability to determine easily when federal assistance will be available to carry out the many projects necessary for recovery in the aftermath of a disaster means that recovery outcomes are driven by such ambiguous timelines rather than by a more clear, logical, and integrative process (Smith, 2011). This ambiguity has widespread effects, especially on the ability to consider the interconnected nature of post-disaster recovery activities, such as the removal of debris, the repair of damaged infrastructure, and the reconstruction of damaged neighborhoods (see Box 4-2).

Each additional governmental layer increases the complexity and uncertainty of the post-disaster recovery process. Rules for federal programs can delay the timing of the delivery of funds. The administration of Hazard Mitigation Grant Program funds, for instance, can be delayed for extended periods of time (Smith, 2011). Individual grant recipients, such as homeowners slated to have their homes acquired, frequently must wait more than a year to receive these funds.21 The agencies responsible for the adminis-

________________

20 In North Carolina following Hurricane Fran, the state required communities receiving Hazard Mitigation Grant Program funds to develop hazard mitigation plans. This requirement predated the similar stipulation adopted by FEMA under the Disaster Mitigation Act of 2000.

21 Developing a pre-disaster hazard mitigation project can speed up the administration of federal program funds. Such a project, when linked to a disaster recovery plan that provides a method for post-disaster decision making, can improve the efficiency and efficacy of future post-disaster federal assistance. The value of the development of such a project is exemplified in the following case, which compares the post-disaster recovery process between two disasters that struck the same community: “Following Hurricane Fran, which struck North Carolina in 1996, it took one year to develop and approve the acquisition of approximately 360 flood-damaged homes using HMGP funds. After all of the available HMGP funds were expended, Kinston, North Carolina developed a HMGP application in anticipation of a future disaster and the release of additional funding. The grant was developed in close coordination with state and federal officials, all of whom had gained valuable knowledge in the development of an eligible grant application following Hurricane Fran. Three years later, Hurricane Floyd struck, devastating the town again. This time, it took approximately one week to have a grant approved for the acquisition of more than 300 homes and funds began to flow into the community shortly thereafter” (Smith, 2011).

BOX 4-2

Challenges in Merging Funding Streams for Disaster Recovery Projects

After a major disaster, many communities express a desire to “build back better” (e.g., in a way that improves quality of life and/or strengthens resilience). However, requirements attached to federal recovery funds and the staggered timing of different grant programs can pose significant challenges to making such improvements. For example, Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) Public Assistance funds typically cover the cost (minimum of 75 percent) of restoring an eligible building to its original size or design capacity and function (FEMA, 2014b). Other federal funds (e.g., Community Development Block Grant for Disaster Recovery [CDBG-DR]) can be used to cover nonfederal cost shares and to finance improvements that are not covered by FEMA’s Public Assistance program (duplication of benefits is prohibited). However, because CDBG-DR funds are dependent on a congressional appropriation, they may not be available as quickly as Public Assistance funds, necessitating delays in reconstruction. These kinds of delays can create a public outcry as community members seek a return to normalcy, thus deterring community betterment projects. Transparency and effective communication with the public are needed to ensure broad understanding that delays associated with betterment will ultimately yield positive change and improved quality of life in the community.

tration of such federal programs are located in a number of regional offices throughout the United States. The timeliness of funding is impacted by the capacity of these agencies to manage these programs, which varies dramatically depending on the staffing levels and post-disaster experience of each regional office. Variations in staffing capacity and post-disaster experience also characterize state and local agencies that administer federal grants, including the Hazard Mitigation Grant Program, Public Assistance, and the CDBGs. These variations, too, influence the speed with which federal funds reach the local governments and individuals carrying out the post-disaster recovery process (Smith, 2011; Smith et al., 2013).

As discussed earlier, coordination challenges can arise from the siloing of FEMA (specifically Hazard Mitigation Grant Program) and HUD CDBG-DR funding streams, both of which can be applied to hazard mitigation activities such as buyouts. In some cases, moreover, state grantees may choose to fund recovery activities directly rather than passing funds on to local governments. Should a city and the state in which it is located both receive CDBG-DR funding, the challenges for coordination are further increased. In such situations, proactive coordination among the administering agencies will be needed to merge the funds effectively. Public officials such as mayors and governors are key in ensuring such coordination occurs, but they may not always agree on spending approaches (Fossett, 2013).

OVERCOMING BARRIERS TO COORDINATION OF FUNDING TO SUPPORT A HEALTHY COMMUNITY APPROACH TO RECOVERY

There are two main mechanisms by which to drive use of disaster recovery funding to achieve a desired outcome—technical requirements and financial incentives. Both have been used successfully to advance other desired activities, such as hazard mitigation, and could likewise be used to overcome barriers that impede the post-disaster realization of healthier communities.

Technical requirements attached to funding programs are a powerful means of advancing a desired outcome and even best practices. This approach currently is being used by the federal government to foster resilience and sustainability in areas affected by a disaster. After Hurricane Sandy, for example, HUD required recipients of CDBG-DR funds to rebuild using green building standards, which, as discussed in more depth in Chapter 10, have been linked to improved health outcomes. Such requirements, however, should be considered carefully and ideally with input from stakeholders representing potential grantees because they increase the restrictiveness of funds, and this, as noted earlier, has been identified as a major impediment to the development of creative solutions that meet local needs.

In addition, funding agencies need to work to align the requirements for different grant programs around agreed-upon goals because diversity of requirements among funding sources creates a burden for applicants, and the requirements may even conflict, preventing the use of different funding streams in a cumulative manner to support large, multifaceted initiatives. Collaboration among funders is required to achieve the necessary coordination. The Partnership for Sustainable Communities, a joint effort of the U.S. Department of Transportation, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, and HUD, provides a model for how this coordination has been accomplished in a steady-state context (DOT et al., 2014). One mechanism that can aid such coordination efforts is establishment of a funding eligibility matrix tied to mutually agreed-upon goals.22

In recent years, financial incentives have been used to drive more progressive approaches to pre-disaster planning and resilience building. A similar approach may be warranted to catalyze the paradigm shift needed to facilitate a healthy community approach to recovery. The examples discussed below, while not exhaustive, could be examined for their applicability to incentivizing pre- and post-disaster investments in healthier communities.

Financial Incentives for Pre-Disaster Planning and Action

Several existing programs can serve as models for how pre-disaster planning can be supported through financial incentives:

- According to the Disaster Mitigation Act of 2000,23 only communities with hazard mitigation plans in place prior to a disaster are eligible to receive Hazard Mitigation Grant Program funds for mitigation activities after a disaster.

- The Community Rating System provides a mechanism for incentivizing pre-disaster efforts to minimize flood damage for communities with flood insurance through the National Flood Insurance Program. The program is voluntary, but as communities undertake more extensive mitigation efforts, premiums are reduced. Policy holders in the Class 1 category have their premiums reduced by 45 percent.

- FEMA recently initiated a pilot program, authorized by the Sandy Recovery Improvement Act of 2013, to incentivize pre-disaster planning for timely debris clearance. Communities with FEMA-approved plans in place prior to a disaster receive a 2 percent increase in the federal cost share for debris removal using FEMA Public Assistance funds. FEMA provides a list of criteria that debris removal plans must meet to be accepted.

________________

22 This section draws on a paper commissioned by the Committee on Post-Disaster Recovery of a Community’s Public Health, Medical, and Social Services on “Disaster Recovery Funding: Achieving a Resilient Future?” by Gavin Smith (see Appendix B).

23 Disaster Mitigation Act of 2000, Public Law 106-390, 106th Cong., H.R.707 (October 30, 2000).

Rebuild by Design is a competition sponsored by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) that is intended to spur redevelopment of resilient communities in Hurricane Sandy-impacted areas. The competition represents a collaboration among HUD, the Presidential Hurricane Sandy Rebuilding Task Force, and the Rockefeller Foundation, with financial contributions from other foundations. The competition’s purpose is to protect communities that are most vulnerable to ever-more-intense weather events. The competition brings together the nation’s most talented designers with the Sandy-affected area’s active businesses, policy makers, and local groups to seek ways of redeveloping in an environmentally and economically healthier manner.

On April 3, 2014, HUD selected 6 winning designs from 10 finalists following 5 months of heightened analysis and public outreach to the populations living and working in Sandy-affected areas. Many of the proposals included measures that would increase not only the resilience of the area but also sustainability and ultimately health (Rebuild by Design, 2014b).

One of the winners was the “New Meadowlands Park and City,” from a team of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and several design firms. This $150 million project provides an integrated vision for protecting, connecting, and growing a land area—the Meadowlands basin—that is vital to both New Jersey and nearby metropolitan New York. The project weaves together transportation, ecology, and development to transform the Meadowlands basin into an area that can withstand a broad range of environmental risks, while also providing urban amenities, parks, and new opportunities for development. The project utilizes a series of intricate berms and marshes to protect against ocean surges, to collect rainfall, and to reduce sewer overflows in nearby towns. An aim of the project is to shift zoning from suburban to urban, with the expectation that doing so will enhance the identity of the basin, raise the value of the land, and provide for higher tax returns (Rebuild by Design, 2014a).

Competition-Based Incentives for Innovation and Resilience

In response to recommendations in the report of the Hurricane Sandy Rebuilding Task Force, HUD and its partners initiated a competition-based effort—Rebuild by Design (see Box 4-3)—to stimulate innovation in recovery approaches and promote multisector collaboration (notably public–private partnerships). According to HUD (2013b): “The goal of the competition is two-fold: to promote innovation by developing regionally-scalable but locally-contextual solutions that increase resilience in the region, and to implement selected proposals with both public and private funding dedicated to this effort. The competition also represents a policy innovation by committing to set aside HUD Community Development Block Grant Disaster Recovery funding specifically to incentivize implementation of winning projects and proposals.” Rebuild by Design is considered so successful—it garnered recognition as one of CNN’s Best Ideas for 2013—that it serves as a model for another new competition, the National Disaster Resilience Competition, announced by President Obama in summer 2014. That competition will be funded by $1 billion set aside from the CDBG-DR program. Communities that have been through natural disasters are invited to compete for funds to assist in rebuilding and increasing their resilience to future disasters. HUD is setting aside $181 million of that amount for applications from the states of New York and New Jersey and from New York City because of the catastrophic damage caused in those jurisdictions by Hurricane Sandy (HUD, 2014c). The competition is intended to spur creative resilience projects at the local level while also motivating communities to plan for the effects of extreme weather and climate change. While promising, however, this initiative does not address the need for support for pre-disaster planning since the competition is limited to communities that have recently been impacted by a natural disaster (HUD, 2014c).

SUMMARY OF FINDINGS AND RECOMMENDATION

The decisions made by those leading recovery efforts at the local level are inevitably based on the resources available to them. Through the Stafford Act, and in some cases supplemental appropriations from Congress, significant federal resources are made available to facilitate the rebuilding of communities, including many of the elements that contribute to healthy communities (e.g., housing, community centers). State and local governments, philanthropies, and the private sector also are key sources of recovery funding, particularly if there is no federal declaration of a major disaster. The amendments to the Stafford Act and other provisions of the Sandy Recovery Improvement Act represent a promising step forward in terms of removing impediments to rebuilding in ways that are forward thinking. However, the delivery of funding in isolation, which places the onus on communities to overcome barriers to coordinated use of the funds, remains a major challenge to achieving healthy community outcomes through recovery actions. Funding organizations need to better facilitate the coordinated expenditure of pre- and post-disaster funding. The first step to this end is broadening the understanding of resources that each stakeholder provides and the timing of assistance, as well as the various interests represented by funding organizations. Although a number of reports, websites, and other sources describe individual recovery programs,24 funders need to seek opportunities to align around mutually compatible policies, which will have the dual benefit of coordinating the distribution of funds and reducing duplicative and counterproductive efforts.

Diverse resources are made available for rebuilding community features that impact health. Some federally funded rebuilding efforts focused on resilience and sustainability, such as those meeting HUD’s requirement after Hurricane Sandy that communities applying for CDBG-DR funds rebuild green, may ultimately contribute to health. However, the various resources available to fund rebuilding generally are not mobilized with the explicit intent of improving community health status. The committee concludes that communities are missing opportunities in post-disaster recovery efforts to maximize resources devoted to health. Using mutually agreed-upon goals and policies to drive the coordinated use of resources, funders need to ensure that financial resources are mobilized more effectively by recovery decision makers to create healthy communities.

Recommendation 6: Leverage Recovery Resources in a Coordinated Manner to Achieve Healthier Post-Disaster Communities.

Federal agencies (the Federal Emergency Management Agency [FEMA], the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development [HUD], the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services [HHS], the U.S. Department of Transportation [DOT], and other federal partners) providing funding for recovery, including pre-event recovery planning, should lead and promote an integrated recovery approach by

- aligning technical requirements and guidance for federal recovery funding opportunities within and across agencies around identified core needs;

- including a requirement and financial incentives for grantees to demonstrate how health considerations will be incorporated into short- and long-term recovery planning conducted using those funds; and

- identifying and removing disincentives that impede the coordination of efforts and the combining of different funding streams to support a healthy community approach to recovery.

Working with private and philanthropic organizations, elected and public officials should ensure that state and local funding regulations and guidelines are consistent with these federal integration efforts.

________________

24 For example, descriptions of disaster recovery programs can be found in FEMA disaster assistance guides (see http://www.fema.gov/pdf/rebuild/ltrc/recoveryprograms229.pdf and https://www.fema.gov/media-library/assets/documents/31850) and through the National Disaster Recovery Program Database at http://www.fema.gov/national-disaster-recovery-program-database (accessed March 4, 2015).

Annex 4-1

Funding for Disaster Recovery

TABLE 4-1 Funding for Disaster Recovery

| Recovery Area | Source of Funds | Funding Pathway | Use of Funds (with notable restrictions) | ||||||

| Pre-disaster Funding | |||||||||

| Pre-disaster Mitigation | Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) | Federal→state or local government | The Pre-Disaster Mitigation (PDM) program furnishes funds for hazard mitigation planning and projects on an annual basis. The PDM program was established to reduce overall risk to people and structures while reducing reliance on federal funding should an actual disaster occur. “Hazard mitigation is any sustained action taken to reduce or eliminate long-term risk to people and property from natural hazards and their effects” (FEMA, 2013a, p. 7-1). | ||||||

| Hospitals and Health Care Systems | Office of the Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response (ASPR) | Federal→state or local government | ASPR’s Hospital Preparedness Program (HPP) provides cooperative agreements to state and local agencies for strengthening their capabilities in the areas of “health care system preparedness, health care system recovery, emergency operations coordination, fatality management, information sharing, medical surge, responder safety and health, and volunteer management” (ASPR, 2012, p. vii). | ||||||

| Recovery Area | Source of Funds | Funding Pathway | Use of Funds (with notable restrictions) | ||||||

| Public Health | Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) | Federal→state or local government | CDC’s Public Health Emergency Preparedness (PHEP) cooperative agreements are provided to state and local health departments for developing the following capabilities needed to respond to a health emergency: community preparedness, community recovery, emergency operations coordination, emergency public information and warning, fatality management, information sharing, mass care, medical countermeasure dispensing, medical material management and distribution, medical surge, non-pharmaceutical interventions, public health laboratory testing, public health surveillance and epidemiological investigation, responder safety and health, and volunteer management (CDC, 2011). | ||||||

| Emergency Management | FEMA | Federal→state | The purpose of the Emergency Management Performance Grants (EMPG) Program is to assist state, local, territorial, and tribal governments in preparing for all hazards, as authorized by the Robert T. Stafford Disaster Relief and Emergency Assistance Act. The act authorizes FEMA to make grants for the purpose of “providing a system of emergency preparedness for the protection of life and property in the United States from hazards and to vest responsibility for emergency preparedness jointly in the federal government and the states and their political subdivisions” (FEMA, 2015b). | ||||||

| Homeland Security | FEMA | Federal→state | The Homeland Security Grant Program (HSGP) supports “the building, sustainment, and delivery of core capabilities” essential to achieving a secure and resilient nation. The funds support core capabilities across five mission areas: prevention, protection, mitigation, response, and recovery from acts of terrorism or other catastrophic events (FEMA, 2014c). | ||||||

| Recovery Area | Source of Funds | Funding Pathway | Use of Funds (with notable restrictions) | ||||||

| Housing Private housing | FEMA | Federal→homeowner | FEMA’s Individual Assistance grants are for homeowners to rebuild damaged properties. There is a $32,400 limit per homeowner.a The funds may be used for rental assistance; lodging expenses; home repairs; home replacement assistance; housing construction; personal property; moving and storage; transportation; and disaster-related medical, dental, and funeral expenses. | ||||||

| Private homeowner’s insurance | Private→homeowner | Homeowner’s insurance payouts are made according to the contract between the insurance agency and the homeowner. | |||||||

| Small Business Administration (SBA) | Federal→homeowner or renter | SBA provides low-interest disaster loans to homeowners or renters. SBA “disaster loans can be used to repair or replace the following items damaged or destroyed in a declared disaster: real estate and personal property” (SBA, 2015). | |||||||

| Public and private housing | U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) | Federal→state or local government (supplemental appropriation) | HUD’s Community Development Block Grant-Disaster Recovery (CDBG-DR) can be used to rebuild homes and buildings, contingent on a presidential disaster declaration. Recipients must demonstrate a logical connection between the impacts of the covered disaster and the activity’s contribution to community recovery (HUD, 2013a). Generally, at least 70 percent of the total grant must benefit persons of low and moderate income (HUD, 2015). | ||||||

| Public Infrastructure | FEMA | Federal state (local government or nonprofit organizations can be subgrantees) | “Through the Public Assistance program, FEMA provides supplemental federal disaster grant assistance for debris removal, emergency protective measures, and the repair, replacement, or restoration of disaster-damaged publicly owned facilities and the facilities of certain private nonprofit organizations” (FEMA, 2015c). Grants often are for rebuilding schools, municipal buildings, public hospitals, sewer systems, communication systems, and fire stations. Grantees generally are required to supply a 25 percent nonfederal cost share. The grants are contingent on a presidential disaster declaration (FEMA, 2015c). | ||||||

| Municipal bonds | Bondholders→ municipalities | Cities borrow money from bondholders to finance municipal projects. Interest is usually tax free. | |||||||

| Recovery Area | Source of Funds | Funding Pathway | Use of Funds (with notable restrictions) | ||||||

| Hazard Mitigation | FEMA | Federal→state | FEMA’s Hazard Mitigation Grant Program (HMGP) is intended to ensure that the opportunity to implement critical mitigation measures to reduce the risk of loss of life and property from future disasters is not lost during the reconstruction process following a disaster. Grants are provided only after a presidential disaster declaration. Grantees are required to supply a 25 percent nonfederal cost share. States are required to develop pre-disaster hazard mitigation plans to be eligible for funding (FEMA, 2007). | ||||||

| Business/Economic Development | SBA | Federal→business | SBA provides low-interest disaster loans to businesses of all sizes and private nonprofit organizations. “SBA disaster loans can be used to repair or replace the following items damaged or destroyed in a declared disaster: real estate, machinery and equipment, and inventory and business assets” (SBA, 2015). | ||||||