Behavioral health1 problems and disorders are among the most frequent adverse health effects after exposure to a disaster—this despite chronic underreporting due to the stigma often associated with these conditions, the lack of visible or physical wounds, the separation of mental health services from medical services, and the lag time between exposure and the onset of disorder. Almost everyone in a community struck by a disaster will feel some type of emotional effect. For most, the acute reactions will be transient, and functional recovery will occur without intervention. For some, however, the impacts of a disaster on behavioral health can be severe and long-lasting, and if not addressed, can impede the recovery of individuals, families, and communities, resulting in significant long-term health burdens. Consequently, it is critically important to identify those individuals at risk for more severe and persistent psychopathology after a disaster and link them with the appropriate preventive and/or rehabilitative services. To this end, however, significant pre-disaster planning is required to establish clear roles and responsibilities for the myriad stakeholders at all levels, an agile and resilient system for delivery of behavioral health services, and a process for evaluating the needs for those services and ensuring that those in need are receiving timely and effective treatment. Where such conditions do not exist in advance, the disaster recovery process can represent an opportunity for advancing toward that more optimal state.

This chapter examines the linkages among behavioral health, resilience, and healthy communities; activities that mitigate adverse behavioral health effects in survivors; the gaps in the current system for addressing disaster-related behavioral health needs; and the opportunities for strengthening the behavioral health sector and integrating it with other sectors by leveraging disaster-related resources and experiences. Based on documented expert consensus on the important elements of behavioral health interventions (Watson et al., 2011, p. 485), the committee proposes the following key recovery strategies for the behavioral health sector that should cut across all phases of the disaster cycle and that represent recurring themes throughout this chapter:

________________

1 For the purposes of this report, the term “behavioral health” encompasses “the interconnected psychological, emotional, cognitive, developmental, and social influences on behavior, mental health and substance abuse” (HHS, 2014, p. 4).

- Integrate behavioral health activities and programming into other sectors (e.g., education, health care, social services) to reduce stand-alone services, reach more people, foster resilience and sustainability, and reduce stigma.

- Provide a spectrum of behavioral health services and use an approach based on stepped care (from supportive intervention to long-term treatment).

- Maximize the participation of the local affected population in recovery planning with respect to behavioral health, and identify and build on available resources and local capacities and networks (community, families, schools, and friends) in developing recovery strategies.

- Promote a sense of safety, connectedness, calming, hope, and efficacy at the individual, family, and community levels.

BEHAVIORAL HEALTH IN THE CONTEXT OF A HEALTHY COMMUNITY

Behavioral health and its integration with health promotion, health care, education, and social services are increasingly appreciated as essential to the realization of healthy communities and healthy individuals (SAMHSA, 2003). The U.S. surgeon general’s landmark 1999 report on mental health significantly advanced the nation’s understanding of these conditions and their importance to the overall health of the American population:

“(M)ental health” and “mental illness” … may be thought of as points on a continuum. Mental health is a state of successful performance of mental function, resulting in productive activities, fulfilling relationships with other people, and the ability to adapt to change and to cope with adversity. Mental health is indispensable to personal well-being, family and interpersonal relationships, and contribution to community or society. (HHS, 1999, p. 4)

In the context of this report, the observation that good behavioral health is key to the ability to adapt to change and cope with adversity (i.e., resilience) is of particular importance. Additionally, the surgeon general’s report emphasizes the importance of viewing mental health through a public health lens. It asserts that public health has a critical role in identifying risk factors for mental illnesses and in undertaking interventions to prevent their emergence and promote overall mental health. These concepts are reinforced by the recent Healthy People 2020 report (Secretary’s Advisory Committee, 2010). Despite the increased attention to mental health conditions resulting from these reports, however, these conditions remain among the most frequent causes of disability. The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) reports that an estimated 9.6 million American adults are afflicted by a serious mental illness on an annual basis (SAMHSA, 2013b). In the United States, mental health disorders are the leading cause of disability, and these conditions account for a quarter of all years of life lost to disability and premature mortality (NIH, 2014). Moreover, approximately 40,000 Americans take their own lives each year; suicide ranks as the tenth leading cause of death in the United States (CDC, 2014, 2015).

Unfortunately, the consensus among experts is that behavioral health still does not receive the attention it deserves. Specific to the committee’s focus on the interrelationship between healthy communities and disaster experiences, the committee was concerned to hear testimony that long-term behavioral health planning and programming are not adequately considered by federal, state, and local disaster and health officials in post-disaster recovery planning (Herrmann, 2014; NBSB, 2010; North and Pfefferbaum, 2013). And although the committee does note growing awareness of the importance of improving the delivery of mental health care, as evidenced by vigorous legislative and other efforts under way to ensure parity in reimbursement2 for treatment of mental health disorders and medical clinical care, as well as greater coordination between the two (AHA, 2012; Goodell, 2014), much more effort in this regard is required.

Pertinent to the goals of this report, it is important to gain a better understanding of how to optimize

________________

2 Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act of 2008, Public Law 110-343, Title V, Subtitle B, 110th Cong. (October 3, 2008).

the integration of behavioral health planning components into overall healthy community planning; how to incorporate the consultation of behavioral health professionals (e.g., leadership and policy consultation, assistance with behavioral health needs assessments, advice on risk and crisis communications, program evaluation) into pre-disaster planning; and how to use the opportunities and resources available along the disaster recovery continuum appropriately to advance toward the realization of more mentally healthy communities and, ultimately, healthier communities overall.

DISASTER-RELATED BEHAVIORAL HEALTH CHALLENGES

Disasters affect the biological-physical, psychological, and sociocultural well-being of survivors in a number of ways, including

- the acute psychological trauma of the disaster itself (including the bereavement associated with the loss of loved ones), whose effects can be immediate or delayed;

- the stress and upheaval associated with the cascade of adversities experienced in the post-disaster environment, such as displacement from homes, challenges in accessing disaster relief benefits, loss of business revenue, uncertainty related to employment, and the increased need to care for others (e.g., children and the frail elderly);

- disruption of health protective medical services, social services, and behavioral health support services;

- disruption of social networks that can leave people feeling isolated and without support (social effects); and

- an increased propensity for risky and destructive behavior, such as cigarette smoking (Vlahov et al., 2002), alcohol abuse and binge drinking (Adams et al., 2006), and domestic violence (Phua, 2008; Weisler et al., 2006).

Patterns of mental illness after a disaster are variable depending upon preexisting local factors and disaster specifics, such as the individual’s direct proximity to the disaster, the number of lives lost, the number of injured (which will impact rehabilitation issues), the extent of damages (which determines the level of disruption of normal activities such as economic and family functioning), the type of disaster (e.g., naturally occurring versus human-caused, novelty of the event); the degree of disruption of behavioral health services/infrastructure; the demographics of the affected population; the resilience of the residents; and the ability of community systems/services to support those in need. As a result, some people within a community may experience more severe adverse behavioral health effects than others. For example, one study conducted after the Oklahoma City bombing in 1995 found that women were more at risk and developed new-onset psychiatric disorders at a rate nearly double that of men (North et al., 2005) (see Table 7-1). Individuals with previous psychiatric disorders may also be at heightened risk following a disaster. The pattern after exposure to Hurricane Katrina was notably characterized by exacerbation of preexisting diagnoses, primarily depression and substance use disorders (North, 2010). The prevalence of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in a sample of residents affected by Katrina increased from a baseline rate of nearly 15 percent, measured 5-8 months after the Hurricane, to nearly 21 percent when measured again one year later (Kessler et al., 2008). Although rates of mental illness of this order of magnitude will present significant challenges to a community’s recovery from a disaster, these data show that even after the most horrific disasters, the majority of the exposed population will not develop diagnosable behavioral health disorders. However, the distress of the event and the recovery process still can generate a wide range of responses—including stress, anxiety, grief, sleeplessness, fatigue, irritability, gastrointestinal distress, and poor concentration (Freedy and Simpson, 2007)—that can interfere with community members’ roles within the family, community, workplace, or school (NBSB, 2010). Beyond the impacts on quality of life for individuals, these long-term behavioral health sequelae have a cumulative negative effect on the functioning of society.

TABLE 7-1 Incidence of Psychiatric Diagnoses After Oklahoma City Bombing

| New-Onset Psychiatric Diagnoses | Men (%) | Women (%) |

| Posttraumatic stress disorder | 19.8 | 35.1 |

| Major depression | 8.0 | 17.0 |

| Panic disorder | 5.8 | 3.2 |

| Generalized anxiety disorder | 0.0 | 5.3 |

| Alcohol use disorder | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Any diagnosis | 20.5 | 40.4 |

SOURCE: North et al., 2005.

Moreover, while most will be resilient in the face of disaster and experience only mild, transient stress reactions, certain populations are especially vulnerable to behavioral health disorders and require targeted outreach and intervention. These populations warrant special consideration and proactive planning to meet their unique disaster recovery needs:

- Children and youth—Children and youth are more likely than adults to be severely impaired after a disaster, most commonly with PTSD or its symptoms (Norris et al., 2002). They also experience anxiety disorders, depression, grief, bereavement, and behavioral and academic difficulties (Pfefferbaum et al., 2014). Children’s vulnerability is dependent upon their age, cognitive level, and degree of exposure to the event, as well as how their parents/caregivers are doing after the event (Pfefferbaum et al., 2014). Parent/caregiver status is of particular importance because children are dependent on adults to identify their needs and to access behavioral health and other support services for them. Problems can arise when caregivers themselves are experiencing symptoms of behavioral health disorders or emotional disturbances. Disasters threaten children’s perception that the world is safe and predictable; thus, recovery for children requires that parents, caregivers, and the community reestablish a protective shield for them (Pynoos et al., 2007). Media portrayals of disasters also can adversely impact children. A number of studies have explored the direct relationship between media coverage and behavioral health problems following disasters. A study conducted after the Oklahoma City bombing found an association between the amount of disaster-related television viewing and PTSD and depression in children (Pfefferbaum et al., 2002). This association has been documented in numerous other studies examining children’s responses to traumatic events, prompting recommendations from researchers (Fairbrother et al., 2003), federal agencies such as the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), and organizations such as the American Red Cross (FEMA and ARC, 2004) to limit children’s disaster-related television viewing.

- Individuals with a preexisting behavioral health disorder (mental illness or substance abuse disorder) and those having experienced prior trauma—Pre-disaster functioning is an important predictor of post-disaster functioning (Dirkzwager et al., 2006). For example, among directly exposed survivors of the Oklahoma City bombing with a mental health disorder, 63 percent had some form of mental illness prior to the bombing (North et al., 1999). Meeting the needs of individuals with preexisting behavioral health disorders requires special consideration to ensure continuity of care throughout response and recovery.

- Responders and recovery workers—First responders and other recovery workers also are at increased risk for developing mental or substance use disorders (Ehring et al., 2011; Flannelly et al., 2005; Mitani et al., 2006; Rosser, 2008). One key study of 27,449 police officers, firefighters, construction

workers, and municipal workers who responded to the September 11 terrorist attacks in New York City found that among police officers, 7.0 percent developed depression, 9.3 percent developed PTSD, and 8.4 percent developed panic disorder (Wisnivesky et al., 2011). Among other rescue and recovery workers, cumulative incidence of depression was 27.5 percent, PTSD 31.9 percent, and panic disorder 21.2 percent. Before the attacks, only 1 percent of these workers had a history of physician-diagnosed PTSD and 3 percent a history of depression (Wisnivesky et al., 2011). Another study, which looked at psychiatric disorders in rescue workers following the Oklahoma City bombing, found that 13.0 percent of firefighters who served as rescue workers developed PTSD (North et al., 2002). Behavioral health impacts in this population can seriously compromise response and recovery efforts by interfering with workers’ abilities to carry out essential job functions.

Other disaster response personnel—including health care professionals and those providing social support and counseling to victims (e.g., social workers, mental health professionals)—are susceptible to burnout and compassion fatigue (reduced capacity to be empathic), which can result from secondary trauma (hearing about the traumas experienced by patients/clients) (Adams et al., 2008). Burnout—“a state of physical, emotional, and mental exhaustion caused by long term involvement in emotionally demanding situations” (Pines and Aronson, 1988, p. 9)—can develop when responders attempt to tackle too much. Compassion fatigue similarly involves the depletion of one’s physical, mental, or spiritual resources. Workers with compassion fatigue frequently suffer from a sense of isolation and may be unable to offer emotional support to their patients (Mendenhall, 2006).

The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ (HHS’s) definition of at-risk individuals3 identifies a number of other population groups that may also be at increased risk for adverse behavioral health outcomes after a disaster. They include senior citizens (e.g., frail elderly displaced from damaged nursing homes), pregnant women, individuals who have disabilities or live in institutionalized settings, people who have limited English proficiency or are non-English-speaking, the transportation disadvantaged, and those with chronic medical disorders (ASPR and ABC, 2012). Vulnerability in many of these populations stems from barriers to their access to behavioral health services such as inadequate finances, lack of health care coverage, language impediments, and difficulties arranging for transportation or daycare. Bridging the language and cultural barriers of different minority groups is a special challenge for successful response and recovery efforts.

BEHAVIORAL HEALTH SECTOR ORGANIZATION AND RESOURCES

The behavioral health sector consists of a fragmented collection of federal, national, state, and local (public and private) resources that “aims to provide a continuum of services and activities—including communication, education, basic support, as well as access to clinical behavioral health services when needed—in order to mitigate the progression of adverse reactions into more serious physical and behavioral health conditions” (HHS, 2014, p. 5). The sector’s roles and responsibilities and the associated challenges related to integrating behavioral health effectively at each level are described in the sections below. Although much of the focus is on those agencies and organizations directly supporting behavioral health services, it is important to remember that the trauma of the event itself is only one contributor to psychosocial sequelae after a disaster. The cascade of challenges experienced by disaster survivors after the immediate threat has passed is a key factor as well; thus, behavioral health interventions can in the broadest sense include all actions that reduce the adversities and associated stress of the short-term response and

________________

3 “Before, during, and after an incident, members of at-risk populations may have additional needs in one or more of the following functional areas: communication, medical care, maintaining independence, supervision, and transportation. In addition to those individuals specifically recognized as at-risk in the All Hazards Preparedness Act (i.e., children, senior citizens, and pregnant women), individuals who may need additional response assistance include those who have disabilities, live in institutionalized settings, are from diverse cultures, have limited English proficiency or are non-English speaking, are transportation disadvantaged, have chronic medical disorders and have pharmocological dependency” (HHS, 2013, p. 1).

long-term recovery periods. By providing accessible small business loans and loans for repair of homes, for example, the Small Business Administration can be viewed as a key federal agency providing a form of behavioral health support, removing one stressor from individuals and families. The same may be said when efforts are made to reopen schools as quickly as possible and to train teachers in how to support students in facing the myriad issues they encounter after a disaster. Such initiatives may be just as beneficial as more traditional behavioral health interventions in reducing individual, family, and community stress.

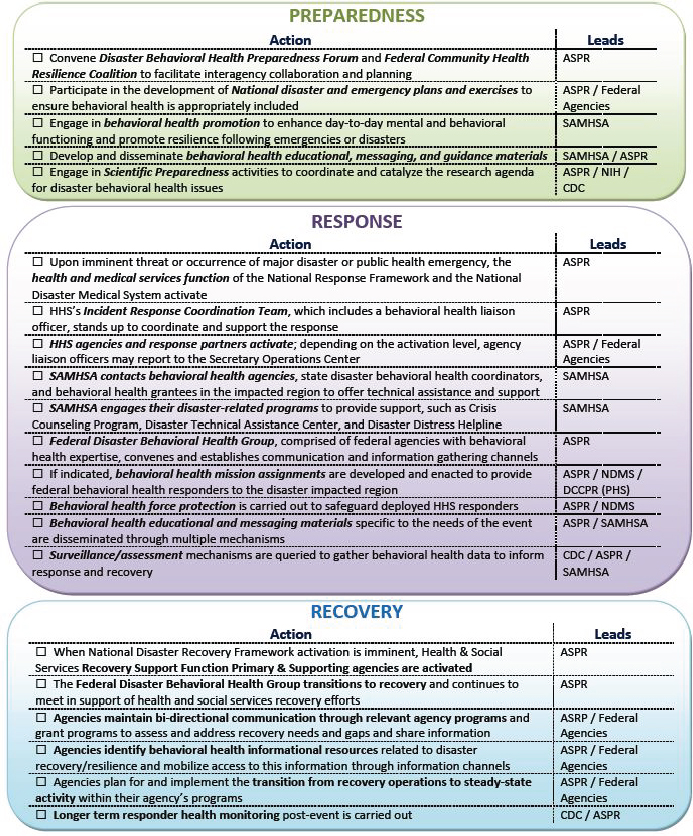

At the federal level, several government agencies carry out an array of behavioral health activities across the disaster continuum (see Figure 7-1). HHS and its subcomponents—including the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response (ASPR), SAMHSA, the Administration for Children and Families (ACF), the Administration for Community Living (ACL), and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)—play key roles specifically in the integration of behavioral health into disaster preparedness, response, and recovery activities (HHS, 2014). Other key federal partners, such as FEMA, the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), the U.S. Department of Education, the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), and the U.S. Department of Defense (DoD), also have important roles in supporting the behavioral health needs of individuals both before and after a disaster.

Although the federal agencies cited above offer an array of resources, both financial and technical, their primary role is to support state and local assets based on locally defined behavioral health needs (HHS, 2014). The availability of many federal resources after a disaster, including behavioral health assets, depends on a presidential disaster declaration even though those that do not receive such a declaration may generate significant mental health needs in the impacted population (Hyde, 2014). Even in the absence of a presidential disaster declaration, however, federal agencies can offer technical assistance and support to current grantees of existing (steady-state) federal programs. It should be noted that mass violence events—which are relevant to this report because, like natural and technological disasters, they can exceed a community’s capacity to recover without outside assistance—result in the activation of different federal services and funding streams in the absence of a presidential disaster declaration.5

As noted above and depicted in Figure 7-1, HHS and its subcomponents, especially ASPR, play a significant role in the preparation for, response to, and recovery from disasters as well as public health emergencies. This role includes providing financial resources in the form of grant funding (cooperative agreements), as well as technical assistance and tools to augment state and local planning and preparedness efforts, including addressing behavioral health. ASPR’s national Hospital Preparedness Program (HPP) grant, discussed in more detail in Chapter 6, is intended to prepare health care systems, both public and private, for the surge in services that typically occurs after a disaster. The program focuses on, among other things, building health care coalitions at the state and local levels to enhance the coordination and integration of disaster planning and response activities (see Boxes 6-3 and 6-6 in Chapter 6 for discussion of health care coalitions). Public and private behavioral health organizations are highly encouraged by ASPR to join and participate actively in these coalitions.

The federal government workforce is also a vital resource, especially during disaster response and early recovery. It encompasses a variety of health care professionals, including behavioral health specialists serving under ASPR’s National Disaster Medical System as well as public health and health care personnel serving as part of the U.S. Commissioned Corps, a program managed nationally by the Office of the Surgeon General within HHS. The ASPR-based Medical Reserve Corps (MRC) program, a network of approximately 1,000 local units comprising volunteers from a variety of health- and nonhealth-related

________________

4 A broader synopsis of legislation and federal policies related to disaster recovery and health security can be found in Appendix A.

5 Examples of federal programs specific to mass violence events include Victims of Crime funding, the U.S. Department of Justice’s Antiterrorism and Emergency Assistance Program for Crime Victims, and the U.S. Department of Education’s School Emergency Response to Violence Program.

FIGURE 7-1 Federal roles in behavioral health preparedness, response, and recovery.

SOURCE: HHS, 2014, p. 7.

professional backgrounds, can be another valuable resource for expanding the nation’s public health and medical response capability (MRC, 2015). The vast majority of MRC units are collocated in public health departments; others are housed in emergency management or law enforcement agencies or are independent, not-for-profit organizations.

Other HHS components play key roles across the disaster continuum. SAMHSA supports “states, territories, tribes, and local entities to deliver an effective mental health and substance abuse (behavioral health) response to disasters” (SAMHSA, 2014b). It develops and disseminates behavioral health educational, messaging, and guidance materials, in addition to providing technical assistance and training manuals for state and local governments to ensure the adoption of behavioral health practices that are evidence-informed. Many of these behavioral health resources (e.g., tip sheets, guidance documents, training resources) are available from SAMHSA’s Disaster Technical Assistance Center6 (SAMHSA, 2014b). Some of the agency’s grant-funded initiatives (e.g., the National Child Traumatic Stress Network) also provide technical assistance, training, and services in the preparedness and recovery phases of a disaster. SAMHSA’s national Disaster Distress Helpline provides a virtual connection with trained professionals offering tips for coping and referral to local crisis call centers (Hyde, 2014). To address post-disaster domestic violence issues, the HHS Administration for Children and Families provides emergency sheltering, statewide services coordination, and the National Domestic Violence Hotline (HHS, 2014).

The Crisis Counseling Assistance and Training Program (CCP), which is funded by FEMA and administered through an interagency agreement with SAMHSA, is the largest federal program supporting short-term disaster-related mental health services. Authorized under the Stafford Act, CCP grants are available only after a presidential disaster declaration and are of two types: the Immediate Services Program, which lasts 60 days, and the Regular Services Program, which lasts 9 months (SAMSHA, 2014a). The main goals of the CCP are to contact a large number of people through face-to-face outreach, to provide basic crisis counseling and connection to community support systems, and to make referrals to traditional mental health or substance abuse treatment services when necessary. CCP-funded services include individual crisis counseling; supportive educational contact; group crisis counseling; assessment, referral, and resource linkage; and media and public service announcements. These services are typically provided by behavioral health staff from organizations under contract to the state or territory mental health authority. CCP funds can be used to train and educate these staff. CCP crisis counselors, consisting of both mental health professionals and paraprofessionals, do not diagnose or treat people with behavioral health disorders, nor are they allowed to create a record of the type of services provided to an individual (FEMA, 2015; HHS, 2014).

Although the CCP is a critical resource for increasing workforce capacity after a major disaster, the committee learned of multiple challenges with the program as currently designed and administered. A number of problems are highlighted in a 2008 report of the U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO, 2008). For example, the administrative aspects of applying for CCP services are time-consuming and cumbersome for states, particularly in the midst of a crisis. According to testimony provided to the committee by SAMHSA (Hyde, 2014), 6 years after release of the GAO report, many of these problems had not yet been resolved. Specific concerns include the following:

- Those seeking the two types of available CCP funds must apply for them separately (funding is not automatic after a presidential disaster declaration), and applicants must demonstrate that no other funding sources are available.

- The application for the Immediate Services Program is due within 14 days of a disaster declaration (FEMA, 2013), when states (and localities) may still be in the midst of the emergency response phase. The time required for review of an Immediate Services Program application, receipt of an award, and contracting and training of service providers means that the time for service provision is significantly less than 60 days—in some cases, less than 30 days—unless an extension request is

________________

6 Resources from SAMHSA’s Disaster Technical Assistance Center can be found at http://www.samhsa.gov/dtac/dtac-resources (accessed November 2, 2014).

-

granted (GAO, 2008). States have suggested extending the length of the Immediate Services Program to 90 days to help alleviate these timing challenges.7

- Applications for the Regular Services Program are due about 6 weeks later (by day 60) and duplicate information from the Immediate Services Program application (FEMA, 2013). Some states have recommended that funding through the Immediate Services Program be made available automatically after a presidential disaster declaration.8 The review process for the Regular Services Program also is lengthy, sometimes necessitating multiple extensions of the Immediate Services Program, which is disruptive to counseling and can delay training of Crisis Counseling Assistance and Training Program staff (FEMA, 2013; Walker, 2014).

- The lack of an electronic system for data collection and reporting to SAMHSA on encounters, assessments, and referrals by crisis counselors creates a large administrative burden by necessitating the compilation of individual paper forms to transfer to the state and, ultimately, SAMHSA.

- Neither CCP grant covers indirect costs, thereby preventing some states from seeking the funds because the local provider agencies often cannot afford to cover those costs.

- Neither mental health treatment (short- or long-term) nor financial coverage for such services is available under the CCP.

Mechanisms for streamlining CCP processes are urgently needed. The committee noted that SAMHSA and FEMA have already initiated a collaborative process to relieve some of the burden of the application process,9 and it applauds these efforts. However, some needed changes (automatic availability of Immediate Services funds after a presidential declaration, support for electronic data collection and reporting systems, and coverage of indirect costs) require congressional action.

It should be noted that although HHS programs, such as those offered through ASPR and SAMHSA, support behavioral health preparedness and immediate response efforts,10 little in the way of post-disaster federal resources and funding to support behavioral health activities during long-term recovery is available from HHS unless there is a supplemental appropriation, such as through the Social Services Block Grant (discussed in Chapter 4). SAMHSA also has a relatively small amount of discretionary funds available through the SAMHSA Emergency Response Grant (SERG) program that can be used for behavioral health services during long-term recovery. For example, these funds were used after Hurricane Katrina to continue methadone treatment for displaced individuals (SAMHSA, 2013a). The annual amount of available funds under this program is modest ($750,000-$1,000,000) (Hyde, 2014), and there is no specific congressional appropriation for SERG funds. Instead, SAMHSA must estimate annually the amount of appropriated discretionary funds that needs to be set aside for this purpose. Consequently, during periods of budgetary constraint, no SERG funds may be available to support disaster-stricken communities (Hyde, 2014). While funding limitations for recovery activities are a particular challenge, the administrative burdens associated with demonstrating need within the allotted time window for applications presents further challenges to states. For example, the committee heard that one state withdrew its request for funding “because providing such information took their time and energy away from directly responding to the people, community and state in crisis.”11

________________

7 Letter, P. Hyde, SAMHSA, to A. Downey, Institute of Medicine, regarding questions posed at Committee on Post-Disaster Recovery of a Community’s Public Health, Medical, and Social Services: Meeting Five, October 7, 2014.

8 Letter, P. Hyde, SAMHSA, to A. Downey, Institute of Medicine, regarding questions posed at Committee on Post-Disaster Recovery of a Community’s Public Health, Medical, and Social Services: Meeting Five, October 7, 2014.

9 Letter, R. Glover, Executive Director, NASMHPD (National Association of State Mental Health Program Directors), to Desk Officer, FEMA, regarding NASMHPD comments on FEMA’s Crisis Counseling Assistance and Training Program (CCP), September 25, 2014.

10 It should also be noted that HHS preparedness funds do not always flow to mental health agencies, which are frequently separate from state public health agency grantees.

11 Letter, P. Hyde, SAMHSA, to A. Downey, Institute of Medicine, regarding questions posed at Committee on Post-Disaster Recovery of a Community’s Public Health, Medical, and Social Services: Meeting Five, October 7, 2014.

National-Level Nongovernmental Resources

A variety of nongovernmental resources and programs are available to assist states, territories, and localities in behavioral health preparedness, response, and recovery. Nongovernmental organizations, including Voluntary Organizations Active in Disasters (VOAD) such as the American Red Cross, play a key role in providing psychosocial support and spiritual care after disasters. Under its congressional charter, the Red Cross provides an array of services and offers substantial behavioral health capacity for disasters through its corps of trained mental health volunteers that respond to such events across the country. “Red Cross has well-defined procedures to provide disaster behavioral health support, identify behavioral health needs through triage and assessment, promote resilience and coping, and target interventions—including crisis interventions, secondary assessments, referrals, and psychoeducation” (HHS, 2014, p. 12). Other National VOAD members such as the Salvation Army, Catholic Charities USA, and Save the Children, as well as private organizations such as Doctors without Borders, provide essential services, including psychosocial support, in the immediate aftermath of disaster.

To take advantage of the support offered by these organizations, they and the services they provide must be coordinated and integrated into the overall disaster response. Still, many of these national organizations provide only short-term response and recovery services, leaving the states and localities to address their long-term recovery needs. Thus, expanding the capacity of first responders and other disaster workers is critical, especially for large-scale events in which such state and local resources are limited. The Emergency Management Assistance Compact (EMAC), a program established in 1996 and administered by the National Emergency Management Association, meets this need during states of emergency declared by governors and in presidentially declared disasters. EMAC is a mutual-aid agreement among all 50 states; the District of Columbia; and the U.S. territories of Puerto Rico, Guam, and the U.S. Virgin Islands. It allows for the sharing of personnel, equipment, and commodities across jurisdictions during disasters and is a vehicle through which behavioral health assets can be requested from other member states (EMAC, 2015).

The behavioral health system at the state level varies from state to state, with behavioral health services being offered through a complex web of government, nonprofit, and private-sector agencies. Since the enactment of the Stafford Act, state mental health authorities have been required to have plans addressing the mental health aspects of disasters. In some instances, inadequate planning has delayed federal funding (SAMHSA, 2003). Two years after the events of September 11, 2001, SAMHSA provided preparedness grants to mental health and substance abuse agencies in many states to enhance behavioral health disaster planning. This grant funding augmented that provided at the time by other federal agencies (i.e., the CDC and the U.S. Department of Homeland Security) to build state and local capability for responding to future terrorist events and other emergencies (GAO, 2008). Many of the state grant awardees used the funding to support a designated disaster behavioral health coordinator. This individual was assigned the responsibility of coordinating behavioral health disaster planning and response activities, often working with state emergency management and public health agencies to ensure integration with broader response and recovery operations. Today, all states have such a position (ASPR, 2014). However, with the decline and subsequent elimination of this SAMHSA-specific preparedness funding stream, and despite the advances made in preparedness planning since 2001, the committee found that mental health and substance abuse issues are not adequately integrated into recovery efforts at the state level, and the capacity to do so is widely lacking. A 2013 report from the Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists indicates that fewer than 20 percent of states reported having systems for monitoring the efficacy of mental health services delivered following a disaster and only 15 percent said they had the ability to monitor the population to identify mental health needs arising in the later post-disaster stages (CSTE, 2013). These assessments are

critical to targeting behavioral health services where they are most needed and need to be integrated into existing public health and comprehensive state emergency management planning processes.

Some state mental health authorities and public health agencies have made a concerted effort to prepare for the surge in behavioral health care needs typically seen after a disaster by providing disaster-related mental health education and training to health and mental health clinicians and other providers (Cross et al., 2010). While generally viewed as a local resource, these trained professionals can be activated as a team to respond to incidents within their region or state. Additional efforts are needed at the state level to ensure that local behavioral health teams are integrated into the statewide disaster plan and that adequate training is provided to these professionals to ensure a consistent and coordinated response in the acute aftermath of a disaster. More important, it is essential to ensure that this expanded capacity also is available to meet a community’s long-term behavioral health recovery needs, when more severe and complex behavioral health disorders are more likely to arise.

State financial resources to aid in behavioral health preparedness, response, and recovery are limited. Typically, states rely on federal funding to support behavioral health planning. Federal funding mechanisms previously mentioned in this report, such as the CDC’s Public Health Emergency Preparedness (PHEP) cooperative agreements and ASPR’s HPP grants, offer support to states, territories, and selected metropolitan cities for building and strengthening their behavioral health preparedness and response capabilities. Following a disaster, states also may be eligible for SAMHSA CCP funding, discussed above, which in turn can be used to establish local contracts to train service providers and offer relevant post-disaster crisis services (e.g., crisis counseling).

At the local level, the behavioral health sector consists of a fragmented collection of local mental health agencies, public and private community mental health centers, psychiatric hospitals, general hospitals with psychiatric beds, nursing homes, addiction services, and local networks of behavioral health and other medical providers (primary care physicians, pediatricians).12 Behavioral health services are integrated into other community service systems and institutional settings, including corrections, education, and child welfare. As discussed in Chapter 8, a variety of human services are available at the county/city level that provide support to individuals and families on a day-to-day basis, assisting them with housing, food, and child care services. Having ready access to these agencies and their services after a disaster can greatly mitigate stress due to a disaster and enhance the recovery process.

As mentioned earlier in this chapter, access to behavioral health services can be challenging even in the absence of a disaster. Stigma, diminished capacity to provide such services, and cost contribute to the inadequate availability and utilization of such services. Even if access to such services were improved in the steady-state period, communities might still be faced with a lack of clinicians trained and skilled in disaster-related behavioral health treatments and interventions. Most behavioral health professionals receive no specific training and education in this area during their normal course of study. Greater effort is needed to provide these professionals with the knowledge and skills needed to respond to the myriad behavioral health issues that can be expected to emerge after a disaster among both their existing patients and new patients they will encounter.

To accommodate the surge in behavioral health needs that typically occurs after a disaster, local mental health and emergency management authorities may look to nonprofit and private-sector partners to assist in the community’s behavioral health response. Many local Red Cross chapters provide mental health services following community emergencies such as a fire or motor vehicle accident resulting in fatalities, as well as larger disasters such as floods or tornadoes. As noted above, these services typically

________________

12 Behavioral health service providers receive information and other forms of support from professional organizations such as the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, the American Psychiatric Association, and the American Psychological Association.

BOX 7-1

The Red River Resilience Project

One example of a community-led coalition that emerged to support coordinated behavioral health care following a disaster is the Red River Resilience Project, initiated in Fargo, North Dakota, in the aftermath of a flood. Partners in the coalition, which is led by the local Red Cross chapter, include the county mental health department, health insurers, a university, Catholic Charities, and local mental health centers. The Red River Resilience Project strives to educate the public on simple steps that can be taken toward resilience, such as fostering hope, engaging in active coping, acting with purpose, connecting with others, taking care of oneself, and searching for meaning (Red River Resilience, 2010).

are short-term in nature and, when warranted, often result in referral to other community-based mental health organizations, although on some occasions, the Red Cross has coordinated longer-term support for survivors by organizing community-based coalitions (see Box 7-1). Local Medical Reserve Corps units, alluded to earlier in this chapter, provide an array of medical and nonmedical services, including behavioral health care, at the local level following a disaster.

Disaster behavioral health services also may be delivered through private-sector for-profit organizations under contract to state and local governments or private employers. Examples of these private providers include Crisis Care Network, Kenyon International, and the KonTerra Group. These organizations offer a range of mental health services, including crisis intervention, individual counseling, health promotion, stress management, and psychoeducation. Some states establish contracts with such behavioral health organizations prior to a disaster to ensure the availability of behavioral health workers should such an event occur. Such contracts may be of particular value in those areas in which disasters are recurring events, not only to ensure that their services will be available immediately following a disaster but also to reduce reliance on local providers, who may themselves be suffering the effects of the disaster (Clements, 2014).

Sometimes overlooked, but more recently gaining visibility, are local faith-based organizations, which often are well positioned to deliver spiritual and emotional care both in the immediate aftermath of disaster and during the recovery phase. Although disaster spiritual care has long existed, it only recently has been acknowledged as a critical part of holistic healing for individuals and communities.13 Disaster spiritual care is “a process through which individuals, families, and communities affected by disaster draw upon their rich heritage of faith, hope, community, and meaning as a form of strength that bolsters the recovery process” (National VOAD, 2014, p. 5). A disaster can tear apart the fabric of a community; thus, a critical part of the recovery process is rebuilding a sense of community (e.g., through community gatherings). Disaster spiritual care providers can support this process and also offer individuals grief support for the many kinds of losses that accompany disasters. Disaster spiritual care providers often do not share the same faith as the individuals and families they care for (Massey, 2006); however, they find ways to connect spiritually with those in need of their services in a manner that is supportive and comforting. Bonding of local faith-based groups into an alliance may reinforce the message that spiritual care is appropriate for all people and may diminish concerns about the focus on any one religious group (Paget, 2014).

Other key recovery partners include national (e.g., the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation) and local

________________

13 No government agency has authority over spiritual care, so until recently there were no standards or guidelines for such care. To fill this gap, National Voluntary Organizations Active in Disaster (VOAD), through its Emotional and Spiritual Care Committee, has used a consensus process to develop a number of resources to support the provision of appropriate and respectful disaster spiritual care, including the National VOAD Disaster Spiritual Care Guidelines, released in 2014. For more information, see http://www.nvoad.org/resource-center (accessed October 13, 2014).

foundations. During past disasters, these philanthropic organizations have been important contributors of funding to support behavioral health recovery. For example, the Missouri Foundation for Health provided funding to the Ozark Center, the behavioral health division of Freeman Health System, for behavioral health recovery efforts in Joplin, Missouri, following the May 2011 tornado. These efforts included employment of community crisis workers; telepsychiatry services; and a text/online messaging service that could be used by students to discuss such issues as depression, suicidal thoughts, and family problems (Freeman Health System, 2012).

Finally, the media, including companies representing print, radio, and television communications, can be instrumental local partners in the aftermath of disaster and throughout the recovery process. Early on, effective crisis and emergency risk communication can help alleviate fear among individuals and communities and aid in obtaining compliance with emergency management directions or other response activities. As recovery proceeds, the media can be an important resource for conveying strategies developed by the public and private sectors for improving emotional well-being and resilience, including coping skills and community prosocial activities (i.e., volunteering to help others). At the same time, however, as stated earlier in this chapter, it is necessary to be aware of the potentially negative influences of the media on behavioral health. Media hype following disasters or other traumatic events and repetitive television coverage (e.g., the replaying of footage of the aircrafts crashing into the World Trade Center towers) can amplify feelings of risk and uncertainty (Vasterman et al., 2005) and contribute to behavioral health problems and disorders, especially in children. For adults who have previously experienced traumatic events, such as veterans, media coverage also can exacerbate symptoms of PTSD (Kinzie et al., 2002).

Challenges to Coordination and Integrated Planning

As discussed earlier in this chapter, the number of stakeholders, both public and private, with key roles in supporting behavioral health grows significantly when behavioral health interventions are viewed broadly to include the many activities that reduce adversity and stress during recovery. This multiplicity of individuals and organizations involved in disaster behavioral health requires effective leadership and coordination at all levels. Coordination is required horizontally among the public, nonprofit, faith-based, and private organizations that make up the local behavioral health sector, and it must also extend across other sectors, including local social services (e.g., case management, homeless programs), education, housing, and emergency management. Coordination also is required vertically to encompass state and federal agencies responsible for mental health and overall disaster response and recovery. Information and data sharing (e.g., sharing of electronic health records) and the development of partnerships and coalitions are critical to the coordination function. Unfortunately, coordination remains a challenge for many communities: data and information systems are inadequate; issues related to the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) and confidentiality must be addressed; and behavioral health representatives are not routinely included at the table during planning discussions or in emergency operation centers (CSTE, 2013).

States and localities impacted by disasters have reported frustration associated with the lack of coordination within and across federal agencies, including HHS, HUD, and the U.S. Department of Homeland Security (NBSB, 2010). This lack of coordination results in overlap and duplication, as well as inconsistent guidance. A recent GAO report cites HHS and seven other federal agencies for failing to fully coordinate behavioral health programs targeting those with serious mental illness (GAO, 2015). The report also indicates that federal agencies failed to formally evaluate many of these mental health programs and thus were unable to ensure that the program activities were meeting the needs of those they were intended to serve. This report and its findings have important implications for disaster recovery in that some of the programs cited are those on which vulnerable populations, such as the severely mentally ill, rely to support them both before and after a disaster. The report also emphasizes the importance of establishing a robust evaluation component for programs that receive federal funding to ensure that they are reaching their targeted audiences and that the services they provide are effective.

By virtue of its coordinating role for both Emergency Support Function (ESF) #8 (Public Health and Medical Services) and the Health and Social Services Recovery Support Function (RSF), ASPR has a lead role in coordinating internal and external federal agencies for the purpose of ensuring that behavioral health issues are integrated into public health and emergency preparedness, response, and recovery. In 2014, HHS released the latest version of its Disaster Behavioral Health Concept of Operations (CONOPS), which provides a framework for ASPR’s coordination of federal disaster behavioral health activities (HHS, 2014). Interagency coordination is further promoted by two ASPR-led interagency groups—the Disaster Behavioral Health Preparedness Forum (to support preparedness activities) and the Federal Disaster Behavioral Health Group—both of which can be utilized during a disaster response as well as during the recovery period, as needed (HHS, 2014).

The committee finds HHS’s Disaster Behavioral Health CONOPS to be a welcome improvement in policy making and coordination of the department’s behavioral health response to disasters. Nonetheless, there remains a need for a “clear and directive national policy” to establish behavioral health as an integral component of the response to and recovery from disasters and to delineate the governmental role in this area across all federal agencies (Pfefferbaum et al., 2012). Such a policy is particularly needed for events that do not result in a presidential disaster declaration; in such cases, further guidance is needed regarding the incident command structure, including delineation of the lead federal agency and the mechanisms for coordination among agencies.14 In a 2010 report, the Disaster Mental Health Subcommittee of the National Biodefense Science Board concludes that “the most pressing and significant problem that hinders integration of disaster mental health and behavioral health is the lack of appropriate policy at the highest Federal level. Compounding that problem is the lack of any clear statement as to where the authority to devise, formulate, and implement such policy should reside” (NBSB, 2010, p. 3). Based on a review of the literature, the findings of the Disaster Mental Health Subcommittee’s report, and testimony from key subcommittee members, the committee believes many of these issues and challenges remain salient today.

At the state and local levels, the structural organization of mental health agencies varies widely, which affects both vertical and horizontal coordination and integration of mental health into broader preparedness, response, and recovery efforts (NBSB, 2010). Mental health agencies often are separate from public health agencies, and siloing of these two sectors has been cited as a significant barrier to post-disaster mental health surveillance (CSTE, 2013). Because of the variation in structural organization, states, territories, and localities need to work proactively to overcome barriers to coordination and integration. Moreover, federal policies designed to promote integration need to account for this variation. States have reported that a lack of understanding of state and local structures and capabilities at the federal level has resulted in confusion in guidance materials (NBSB, 2010). Thus, it is important to engage state and local authorities, as well as nongovernmental, professional, and voluntary organizations that provide behavioral health services, in federal efforts to further integrate behavioral health into disaster preparedness, response, and recovery.

Testimony provided to the committee by experts in disaster behavioral health supported conclusions drawn from the literature that there is virtually no emphasis on integrating behavioral health into intermediate- and long-term recovery planning at the state and local levels (Herrmann, 2014). The committee heard that existing behavioral health programs are tailored primarily to meet short-term, immediate needs during the response phase. Although preparedness funds can be used to improve planning for behavioral health during later recovery stages, cutbacks in critical federal funding support from the HPP and the PHEP cooperative agreements pose significant challenges to making such improvements. Indeed, in the face of reduced funding, advances made in the last few years are being eroded as training opportunities are reduced or eliminated (Herrmann, 2014).

________________

14 M. Brymer, National Center for Child Traumatic Stress at University of California at Los Angeles, to A. Downey, Institute of Medicine, comments provided regarding draft Behavioral Health chapter October 30, 2014.

PRE-DISASTER BEHAVIORAL HEALTH SECTOR PRIORITIES

Not only is mental health essential to the realization of a healthy community; it is also a key component of community resilience (Chandra and Acosta, 2010). A resilient community is one that has fewer risk and resource inequities; engages residents in taking significant, resolute, and collaborative action to remedy a problem; creates linkages to various community resources; promotes and maintains healthy social connections; and successfully adapts to adversities in a flexible manner (Norris et al., 2008). The committee identified two key pre-disaster priorities in which the behavioral health sector should be engaged to support pre-disaster resilience building efforts:

- Strengthening the Existing System with Day-to-Day Responsibility for Promoting Behavioral Health and Delivering Behavioral Health Services

- Engaging in Disaster Preparedness and Recovery Planning Activities

To mitigate the behavioral health impacts of disasters (increase resilience) while also building healthier communities, pre-event activities need to focus on strengthening the existing systems with day-to-day responsibility for promoting behavioral health and delivering behavioral health services. Inadequate attention to individuals with prior trauma, for example, can result in a larger population at risk of developing more severe behavioral health disorders after a disaster (HHS, 2014). It is important to stress, however, that during steady-state times, as during recovery, a broad view of behavioral health interventions needs to be taken and the importance of behavioral health to individual and community health emphasized.

Strengthening existing systems is not just about treating those with disorders but also entails preventive measures such as integrating a curriculum for building emotional well-being, coping skills, and social competence into schools to foster healthy students. Another example is the development of programs to foster increased social connectedness15 as part of preparedness activities (HHS, 2014; NBSB, 2014). An inverse relationship between individual-level social capital and mental health disorders has been observed (De Silva et al., 2005), suggesting that stronger social support may be a protective factor that can reduce the risk of post-disaster mental health disorders. An individual’s social network is an important source of emotional support after a disaster (Chandra and Acosta, 2010), and cohesion among family members has been associated with reduced symptoms of PTSD following such events (Birmes et al., 2009). Investment in stronger systems for the delivery of behavioral health services, the integration of preventive behavioral health services into other community systems, and increased social connectedness can build resilience at the individual, family, and community levels, which in turn can reduce disaster-related effects on behavioral health and alter the trajectory of recovery. It is worth pointing out that some primary care practices and patient-centered medical homes are already integrating behavioral health with health care (NCQA, 2014). To encourage such integration, existing payment and reimbursement barriers need to be reduced or eliminated so that patient-centered medical homes can increase their everyday capacity and, as a result, their disaster-related capacity.

Engaging in Disaster Preparedness and Recovery Planning Activities

To ensure that behavioral health providers are prepared to function as part of a coordinated health system after a disaster, they need to be actively engaged in pre-disaster preparedness activities. One mechanism for integrating behavioral health into pre-disaster planning for response and recovery is through exist-

________________

15 An example of an emergency preparedness program focused on increasing social connectedness is SF72, which was developed by the San Francisco Department of Emergency Management. For more information, see http://www.sf72.org/home (accessed April 2, 2015).

ing or newly formed regional (substate) health care coalitions, which, as mentioned earlier in this chapter and discussed in greater detail in Chapter 6, serve as coordinating groups for the health system before and after disasters and provide an interface with the public health and emergency management sectors (ASPR, 2012). As noted earlier, the HPP supports the development of health care coalitions, and according to the National Guidance for Healthcare System Preparedness, behavioral health providers should be considered essential members of these groups. Included among program measures for state-level awardees of HPP funds is an indicator for whether the health care recovery plan, developed in collaboration with the health care coalition, addresses how the community’s post-disaster behavioral health care needs will be met (ASPR, 2013). To ensure a specific focus on behavioral health challenges during planning activities, a behavioral health task force could be formed within the health care coalition. Another task for the health care coalition is to develop adequate continuity of operations plans for mental health agencies, organizations, and facilities providing behavioral health services. These plans should consider the surge in demand arising from the needs of individuals who were not utilizing these services before the disaster.

In addition to pre-event planning, providing disaster-specific training in advance of an event on behavioral health interventions can increase community resilience by enhancing self-sufficiency and enabling the community to better meet the surge in behavioral health needs. This type of training can be provided to community members, behavioral health professionals, and/or community partners. These trained individuals can then form a local disaster behavioral health response team that can be deployed after a disaster to offer supportive interventions that mitigate the acute and long-term behavioral health consequences of the disaster (University of Rochester et al., 2005). For example, one state invested PHEP cooperative agreement funds in a program used to teach community partners how to deliver psychological first aid (described in more detail in the section below), thus creating a cadre of individuals ready to provide behavioral health services when activated in subsequent disasters (Singleton, 2014). The American Red Cross offers a 4-hour training course, Coping in Today’s World: Psychological First Aid and Resilience for Families, Friends and Neighbors, aimed at building community resilience by helping people learn to cope with stresses, including those related to a disaster, as well as to help their fellow community members (ARC, 2010).

To facilitate and expedite the deployment of behavioral health services after a disaster, behavioral health professionals who wish to assist can be encouraged to affiliate with a local or state-based disaster behavioral health team (e.g., American Red Cross, local MRC unit) and register in the Emergency System for Advance Registration of Volunteer Health Professionals (described in Chapter 6) or similar state registries so their credentials can be verified in advance of a disaster. Additionally, memorandums of understanding can be established with community partners who will offer behavioral health services after a disaster to articulate their roles and responsibilities. Participation in pre-disaster drills and exercises will further prepare community members, behavioral health professionals, and community partners to address disaster behavioral health needs.

THE CONTINUUM OF POST-DISASTER BEHAVIORAL HEALTH INTERVENTIONS

As discussed earlier in this chapter, most disaster survivors will not develop major psychological or psychiatric problems but short-term stress reactions that will resolve on their own or through minimal supportive care. Others, however, will go on to develop more significant behavioral health problems that will require more intensive, targeted intervention and treatment. According to Pfefferbaum and colleagues (2012, p. 60), “Timely mental and behavioral health interventions can improve response efficiency, prevent secondary adversities due to inappropriate or inadequate response, help affected populations recover and adjust to changed circumstances, improve adherence to future recommendations and directives, and increase confidence in government.”

Behavioral health interventions help survivors adjust to the consequences of a disaster and its secondary adversities. However, three major challenges are encountered in efforts to deliver effective and adequate behavioral health services after a disaster. First, disasters generate an increased need for services in a system already strained by capacity limitations. Second, this disaster-related surge in mental and behavioral health

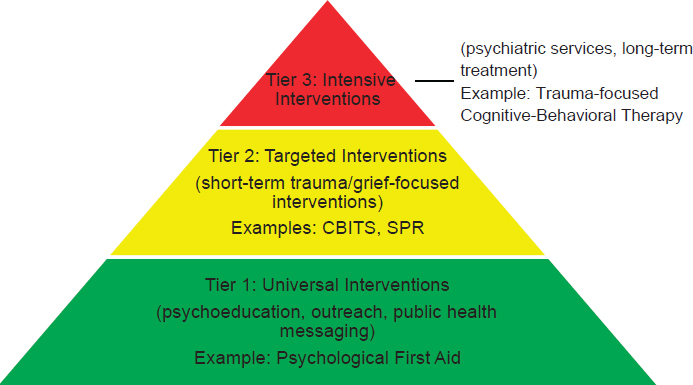

FIGURE 7-2 A 3-tiered public health model for behavioral health interventions after disasters.

NOTE: CBITS = Cognitive-Behavioral Intervention for Trauma in Schools; SPR = Skills for Psychological Recovery.

SOURCE: Adapted from Pynoos et al., 1998.

needs occurs at the same time that the mental health infrastructure is weakened. And third, as discussed earlier, behavioral health systems often are fragmented so that it is difficult to coordinate the efforts of the many actors and sectors involved.

When post-disaster behavioral health needs are not adequately addressed, they can become chronic and subsequently lead to an increased demand for long-term behavioral health services. In the immediate post-disaster stage, interventions need to focus on alleviating the emotional suffering caused by the traumatic events, reinforce short- and longer-term adaptive functioning and coping, provide clear communication aimed at destigmatizing help seeking for those in distress, prevent the progression to mental illness or substance abuse, address the immediate mental health needs of those with preexisting behavioral health disorders, and refer those severely affected to appropriate therapeutic services. While each of these issues presents critical short-term needs, activities should be undertaken with the long-term goal of building a more socially supportive and cohesive environment and a resilient behavioral health infrastructure in which preventive and rehabilitative services are integrated with other community services.

Disasters affect different people in different ways as a result of factors specific to the disaster (e.g., exposure) and the individual (e.g., resilience).16 Thus, different types of support will be required to meet the spectrum of needs within a community. A three-tiered public health approach that offers multiple intervention strategies at different post-disaster time points will ensure that survivors receive services based upon their disaster experience and current needs (see Figure 7-2). With a tiered approach, triage and assessment strategies are needed to determine the appropriate level of care in each case and to target

________________

16 A number of individual resilience factors have been identified and can inform the development and refinement of behavioral health interventions. These include personality traits, attributional style, social support, coping self-efficacy, and a variety of biological factors (Watson et al., 2011).

interventions to priority groups (Pynoos et al., 2007). For example, the Fast Mental Health Triage Tool (Brannen et al., 2013) and Psychological Simple Triage and Rapid Treatment (Schreiber et al., 2014) are examples of triage tools that can assist in identifying individuals who may be at risk of more serious mental health consequences and thus require further assessment from qualified behavioral health specialists. It is important that behavioral health responders and others using these triage tools be trained in their use and understand how to identify the most appropriate level of care based on the symptoms being assessed.

Although there is broad recognition of the value of population-level psychosocial support methods that provide comfort and promote resilience, and several such interventions are discussed in the sections below, the committee recognizes that studies are urgently needed to determine the effectiveness of these methods. Evaluation of other interventions that were once commonly used, such as psychological debriefing,17 has demonstrated the importance of showing not only that interventions are beneficial but also that they cause no further harm. One challenge with evaluation studies, however, is that what constitutes meaningful change as opposed to statistically significant findings may not be clear. In the absence of adequate evidence from research studies, consensus methods are used to inform interventions. For example, a panel of experts on the study and treatment of survivors from disasters and mass violence events developed empirically supported consensus principles that can guide intervention and prevention efforts. Based on expert consensus, early and mid-term interventions should promote “1) a sense of safety; 2) calming; 3) a sense of self- and community efficacy; 4) connectedness; and 5) hope” (Hobfoll et al., 2007, p. 283).

Delivering Early Behavioral Health Interventions

The first priority after a disaster is to ensure that basic needs are met by addressing individuals’ safety concerns; connecting them with their loved ones; providing practical assistance, information, and emotional support; and linking them with other community services (Tier 1 in Figure 7-2). The behavioral health needs of the community must be assessed if appropriate care is to be provided, and at-risk individuals or groups that may need further intervention should be identified during this assessment. If the disaster disrupted the usual provision of behavioral health services, it should be reestablished as soon as possible to assist survivors with preexisting mental health and substance abuse disorders (as well as a possible surge in demand due to the disaster). However, it is important to note that the steady state of behavioral health services often is inadequate for individuals with Medicaid or those lacking health or behavioral health insurance coverage. These are often, not coincidentally, the most vulnerable populations—impoverished children and adults, individuals for whom English is not the primary language spoken, and those who lack U.S. citizenship (ASPR and ABC, 2012). If necessary, mobile services, such as those provided by some community and faith-based organizations, can be used to reach patients when facilities are damaged or patients are displaced. Behavioral health response teams, such as those discussed in the previous section, can be activated after the disaster to begin assisting the community.

Psychological first aid (PFA) is a widely accepted technique used during the response phase by first responders and other disaster workers to address these initial priorities. In 2006, the National Center for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder and the National Child Traumatic Stress Network released the second edition of Psychological First Aid Field Operations Guide, a set of comprehensive guidelines on the definition and use of PFA (Brymer et al., 2006). This guide, produced after consultation with first responders and disaster mental health professionals, as well as disaster survivors, appears to represent the strongest attempt yet

________________

17 Psychological debriefing is “an intervention consisting of one or more individual or group sessions provided hours or days after a traumatic event.” Its goals are to “normalize survivors’ reactions, process their trauma experiences, address psychological distress, [and] enhance resilience.” Its elements include “assist[ing] survivors in sharing their experiences and ventilating their emotional reactions, provid[ing] education about common reactions, [and] encourag[ing] further intervention if appropriate” (North and Pfefferbaum, 2013, p. 514). Psychological debriefing gained popularity internationally without evidence of efficacy. An influential review of numerous randomized controlled trials of single-session debriefing for individuals found that it lacked effectiveness for reducing distress or preventing PTSD and that it could worsen posttraumatic symptoms, but only in those at greatest risk for PTSD (Rose et al., 2002).

made to develop a consensus on guidelines for conducting PFA, which is defined as “a systematic set of helping actions aimed at reducing initial post-trauma distress and supporting short- and long-term adaptive functioning” (Ruzek et al., 2007, p. 17). The core actions for PFA are

- contact and engagement,

- safety and comfort (to enhance immediate and ongoing safety and provide physical and emotional comfort),

- stabilization to promote calm,

- information gathering to identify immediate needs and concerns,

- practical assistance to offer help in addressing immediate needs and concerns,

- connection with social supports,

- information on coping support, and

- linkage with collaborative services (Ruzek et al., 2007).

Psychological first aid can be performed by a wide variety of trained professionals and paraprofessionals in diverse settings, including general-population shelters, special-needs shelters, field hospitals and medical triage areas, schools, acute care facilities, staging or respite centers for first responders, and crisis hotlines or phone banks (Brymer et al., 2006). Training resources for PFA exist across the country and are offered through various organizations, including the American Red Cross (ARC, 2014), the World Health Organization (WHO) (2011), and the Bloomberg School of Public Health at Johns Hopkins University (Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, 2014). One Red Cross program—Coping in Today’s World—can be offered throughout the recovery period to help community members better help themselves, their families, and their neighbors (CDMHC, 2011).

While PFA is a widely accepted and utilized technique within the mental health and disaster recovery communities and has received support from major stakeholders such as WHO, the National Institute of Mental Health, the American Red Cross, and several relief organizations (including The Sphere Project18), it has not been empirically evaluated for efficacy (Watson et al., 2011). Further scientific evaluation of this intervention is essential to determine its value and effectiveness.

Providing Ongoing Psychosocial Support

Following the acute post-disaster stage, one measure for judging the progress of recovery is how people feel they are coping with their lives. During the recovery period, therefore, it is critical to provide community members with the tools and resources they need to cope with the ongoing challenges they face (i.e., a self-help approach). According to Gluckman (2011, p. 2),

A comprehensive and effective psychosocial recovery programme needs firstly to support the majority of the population who need some psychosocial support within the community (such as basic listening, information and community-led interventions) to allow their innate psychological resilience and coping mechanisms to come to the fore, and secondly to address the most severely affected minority by efficient referral systems and sufficient specialised care. Insufficient attention to the first group is likely [to] increase the number represented in the second group.

Although no single evidence-based psychosocial support program can be applied in all communities after a disaster, expert consensus documents highlight the important elements of a disaster behavioral health program (see Box 7-2), as well as evidence-informed and promising models. Ideally, programs should be

________________

18 The Sphere Project brings together humanitarian agencies around the common goal of improving the quality and accountability of humanitarian assistance and actors. The Sphere Project was established in 1997 and is “governed by a Board composed of representatives of global networks of humanitarian agencies.” The Sphere Handbook, Humanitarian Charter and Minimum Standards in Humanitarian Response, offers a set of common guidelines and standards (The Sphere Project, 2015).

BOX 7-2

Expert Consensus on Disaster Behavioral Health Interventions

Commonalities across guidelines and recommendations from expert consensus on disaster behavioral health interventions include the following:

- Be proactive/prepared ahead of time, pragmatic, flexible, and plan on providing the appropriate services matched for phase across the recovery period.

- Promote a sense of safety, connectedness, calming, hope, and efficacy at every level.

- Do no harm, by:

- – participating in coordination of groups to learn from others and to minimize duplication and gaps in response;

- – designing interventions on the basis of need and available local resources;

- – committing to evaluation, openness to scrutiny, and external review;

- – considering human rights and cultural sensitivity; [and]

- – staying updated on the evidence base regarding effective practices.

- Maximize participation of local affected population, and identify and build on available resources and local capacities (family, community, school, and friends).

- Integrate activities and programming into existing larger systems to reduce stand-alone services, reach more people, be more sustainable, and reduce stigma.

- Use a stepped care approach: Early response includes practical help and pragmatic support, and specialized services are reserved for those who require more care.

- Provide multilayered supports (i.e., work with media or Internet to prepare the community at large; facilitate appropriate communal, cultural, memorial, spiritual, and religious healing practices).

- Provide a spectrum of services, including

- – provision of basic needs;

- – assessment at the individual level (triage, screening for high risk, monitoring, formal assessment) and the community level (needs assessment and ongoing monitoring, program evaluation);

- – psychological first aid/resilience-enhancing support;

- – outreach and information;

- – technical assistance, consultation, and training to local providers; [and]

- – treatment for individuals with continuing distress or decrements in functioning (preferably evidence-based treatments like trauma-focused cognitive-behavioral therapy).

SOURCE: Excerpted from Watson et al., 2011, p. 485.