9

Place-Based Recovery Strategies for Healthy Communities

Consider that Detroit, an area of 139 square miles and over 900,000 citizens, has just

five grocery stores. An apple a day may help keep the doctor away but that assumes

you can find an apple in your neighborhood.

—James Marks, Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (Marks, 2009)

As discussed in Chapter 2, the concept of “place matters” has grown in recent years, with many health departments and community groups around the country realizing the connection between health status and social determinants such as transportation, housing, and education. As noted by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation in Time to Act, “place-based differences in health are strongly linked with differences in people’s incomes, educational attainment, and racial or ethnic group” (RWJF, 2014, p. 32). The World Health Organization defines social determinants of health more broadly as “the conditions in which people are born, grow, live, work and age, including the health system. These circumstances are shaped by the distribution of money, power and resources at global, national and local levels, which are themselves influenced by policy choices. Social determinants of health are mostly responsible for health inequities—the unfair and avoidable differences in health status seen within and between countries” (WHO, 2014).

As an example of action to combat some of these place-based health inequities, the Boston Public Health Commission operationalized the concept in 2010 when it launched an interactive “What’s Your Health Code” website to show the variations in health throughout the city depending on the neighborhood and to bring awareness to health equity needs (Boston Public Health Commission, 2010). Other cities have employed various place-based strategies,1 some of which are discussed throughout this chapter, to improve the physical and social environments in communities in hopes of improving the health status of their residents (see Box 9-1 for differences between place-based and people-based interventions). “Place-based policies leverage investments by focusing resources in targeted places and drawing on the compounding effect of well-coordinated action. Effective place-based policies can influence how rural and metropolitan

________________

1 It is important to note that although place-based strategies are geographically targeted, they are not limited to alterations of the physical environment. Place-based strategies often also address the social and economic environments of a community.

BOX 9-1

Place- Versus People-Based Interventions

Although there are a number of ways to define place- versus people-based interventions, the terms are used here as follows:

Place-based—encompasses “real estate- and infrastructure-based activities, including affordable housing preservation and development, commercial development, green space set-asides and improvements, and community facilities including charter schools, health centers, day and elder care centers, and community centers devoted to other community activities and gatherings; transit, communications, and energy improvements.”

People-based—encompasses “child care and job training and placement to enable adults to work and improve their incomes, savings and homeownership programs to help people build assets (but not tied to housing development or rehabilitation), early childhood interventions and charter school services intended to narrow educational achievement gaps, small business development and lending for economic development, community policing and safety, community organizing, and social case work to address special needs like addiction or disabilities or reentry after incarceration.”

People-based interventions are discussed in more detail in Chapter 8.

SOURCE: Belsky and Fauth, 2012, p. 76.

areas develop, and how well they function as places to live, work, operate a business, preserve heritage, and more. Such policies can also streamline otherwise redundant and disconnected programs” (The White House, 2009).

While coordinated, place-based initiatives are strong in theory and academic support, they can be difficult to achieve in practice because of the need for robust collaboration across community agencies, as well as sometimes-significant reallocation of funding. Disaster recovery also requires multi-agency coordination and long-term planning, but it can sometimes be accompanied by more funding and fewer restrictions. Combining these areas of practice and intertwining their goals and policies can have an increased collective impact on a community’s progress toward becoming healthy, resilient, and sustainable. This chapter outlines the evidence behind these theories while highlighting real-life examples that illustrate the effect these types of initiatives can have in practice—both in normal times and during recovery from a disaster.

During this study and throughout its deliberations, the committee identified key place-based recovery strategies that appear as recurring themes throughout this chapter and cut across multiple sectors involved in planning, transportation, sustainability, health, and community development. Application of these strategies, which apply to multiple pre- and post-disaster activities, will facilitate the protection and promotion of health as a community works to meet physical, social, and infrastructure needs after a disaster:

- Reduce health disparities and improve access to essential goods, services, and opportunities.

- Preserve and promote social connectedness.

- Use a systems approach to community redevelopment that acknowledges the connection among social, cultural, economic, and physical environments.

- Seek holistic solutions to socioeconomic disparities and their perverse effects on population health through place-based interventions.

- Rebuild for resilience and sustainability.

- Capitalize on existing planning networks to strengthen recovery planning, including attention to public health, medical, and social services, especially for vulnerable populations.

The chapter concludes with a checklist of key activities that need to be performed during each of the phases of recovery.

A SYSTEMS VIEW OF A HEALTHY COMMUNITY

As discussed in Chapter 2, viewing a community from a systems perspective can help in considering options for rebuilding and holistic recovery. Healthy behaviors do not occur in isolation within a community, so it is important to consider connections among a society’s social, cultural, economic, and physical elements. Simply building a park and a walking trail for residents may not be successful if the trail is not well lit or the park is in an area plagued by crime. In addition to examining how these different systems intersect, it is important to consider how residents in a community are able to access those systems. Rebuilding after a disaster is an opportunity to give these elements a fresh look.

There is growing consensus on the elements that help build a healthy and sustainable community (see Box 2-2 in Chapter 2). This chapter examines some of those elements in the context of the physical and social environments of a community. Specifically, these elements can include clean air, parks and green spaces, a sustainable transportation grid promoting active living, access to nutritious food and clean water, safe communities free of violence, and accessible and integrated community services that can contribute to increased social cohesion. How communities are structured and how public transportation, health care, and social services are built within a city often can dictate the level of access residents have to these and other community services and features. When these elements are not present in a community or their integration is not well designed, making access strained or difficult, adverse health effects can result. The following section expands on this evidence.

The environment in which a person lives influences health in countless ways. The natural and built environments of a community can promote the health of its residents by providing opportunities for physical activity, clean air and water, safe roadways, and access to healthy food and essential services; as noted above, the absence of these elements can hinder health. The physical environment is heavily influenced by a community’s social environment. Neighborhoods with high concentrations of racial minorities or low-income families tend to lack elements that promote health, such as opportunities for activity, and contain elements that hinder health, such as pollution from highways or factories.

Physical Activity and the Environment

Regular physical activity can help reduce or maintain body weight; reduce the risk of cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and some cancers; improve mental health; and increase life expectancy (CDC, 2011). Unfortunately, fewer than half of U.S. adults meet the recommended guideline of 150 minutes of moderate activity per week (CDC, 2014a). Chronic diseases associated with a lack of physical activity plague millions of Americans: more than one-third of adults and 17 percent of children are obese (Ogden et al., 2014), 29.1 million have diabetes (CDC, 2014c), and one in four deaths each year are due to heart disease (Murphy et al., 2013). Inactivity’s burden on the health care system is sizable, with one study estimating the aggregate national cost of overweight and obesity at $113.9 billion (Tsai et al., 2011).

Communities that include parks, sidewalks, and public transit give residents opportunities to be active and can make activity safer and more appealing (Williams, 2007). For example, physical activity levels are higher for people who live near recreational facilities—parks, playgrounds, sports facilities (Sallis et al., 2012)—or whose neighborhood sidewalks are well maintained (Kwarteng et al., 2013). Walking and

biking for transportation are increased when neighborhoods are more densely populated, use a grid pattern, and have commercial areas within walking distance (Transportation Research Board, 2005). People who use public transportation are more active than those who do not, and 29 percent of those who use transit meet the recommended activity level of 150 minutes per week by simply walking to and from transit (Sallis et al., 2012).

When the Austin, Texas, airport was relocated in 1999, the community of Mueller, Texas, was left with 700 acres of what could have been unused space (Mueller, 2014). Instead, Mueller is being redeveloped as a mixed-use urban village as a joint project with the city of Austin. Following a Texas A&M study sponsored by the American Institute of Architects, researchers found that nearly three of four residents reported more physical activity after joining the new community. They found that such elements as sidewalks, parks, open space, and bike routes, along with diverse uses and destinations, supported more physical and social activity (ULI, 2013).

Air and Water Pollution

John Snow famously demonstrated the link between environment and health when he mapped the public wells in his London neighborhood along with the location of cholera deaths. Noticing a cluster around one particular well, he lobbied local authorities to remove the handle from the pump, and the outbreak subsided. Today, environmental threats to communities include particulate air pollution associated with motor vehicle traffic and industrial facilities, and poor water quality related to stormwater management.

Air becomes polluted with particles when mechanical or chemical processes—such as construction, agriculture, or burning of fossil fuels in cars or factories—create tiny particles of chemicals, metals, and other pollutants that are inhaled. This pollution is linked to short- and long-term health issues including respiratory and cardiovascular diseases, cancer, inflammation of lung tissue, exacerbation of asthma, infant mortality, and decreased life expectancy (State of the Air, 2013). The air quality of a community is influenced by its characteristics; for example, industrial plants or large agriculture operations in a community will produce particulate pollutants, while motor vehicles contribute to more than 50 percent of the air pollution in urban areas (CDC, 2009). Altering the built environment of a community to eliminate or diminish these elements may reduce pollution. For example, to accommodate the visitors to the 1996 Olympic Games, Atlanta developed an extensive public transportation system, encouraged telecommuting, and closed the downtown to private automobiles. As a result, peak weekday morning traffic was reduced by 22.5 percent, and there were measurable decreases in air levels of ozone, carbon monoxide, and nitrogen dioxide. During this time period, the number of children seeking acute care or hospitalization for asthma events was significantly reduced (Friedman et al., 2001). This example starkly demonstrates the close relationship among environment, pollution, and health and suggests that changes in the community environment can have an immediate impact on residents’ health. Using “green,” or environmentally friendly, infrastructure also can lower air temperatures, which is valuable in tightly packed urban areas that suffer from the “urban heat island” effect (ASLA, 2010). Another study found that large numbers of trees and green spaces throughout a city can reduce the local air temperature by 1-5 degrees Celsius (McPherson, 1994).

The water quality in a community is affected in part by stormwater management. Stormwater runoff can pollute drinking and recreational water with harmful pathogens such as Cryptosporidium, Giardia, and E. coli, as well as pollutants such as heavy metals, insecticides, and excess nitrogen. While community drinking water is usually treated, several common microorganisms are resistant to treatment and remain in the water (Gaffield et al., 2003). These waterborne pathogens can cause illness and death. In Milwaukee, for example, an outbreak of Cryptosporidium spread via the public water supply and sickened 403,000 people (Mac Kenzie et al., 1994) and contributed to the deaths of 54 people (Hoxie et al., 1997). Contamination by stormwater runoff is more likely when a community has large impervious surface areas, such as roads and parking lots (Gaffield et al., 2003). Runoff can be controlled, and water contamination reduced,

by adding such features as green parking lots, grassed swales, permeable pavement, and vegetation. These types of “green infrastructure” allow stormwater to be absorbed by the ground rather than into the city water system or a nearby waterway. A program in Michigan, for example, diverted roof downspouts into yards rather than into the sewer system. This simple change reduced the flow of stormwater into sewers by up to 62 percent, thus reducing both the cost of water treatment and potential contamination (Kaufman and Wurtz, 1997). Green absorbent infrastructure, while aesthetically pleasing, also can be the most cost-effective way to manage stormwater, in addition to appreciating in value over time and providing multiple uses (Francis, 2010). Elements such as rain gardens or green roofs can mitigate flooding and pollution of the aquifer. One inch of rainwater hitting 1 acre of asphalt produces 27,000 gallons of stormwater over the course of 1 hour (Elmendorf, 2008).

Injuries Associated with Unsafe Streets

Millions of people are injured or killed each year on the nation’s roads. In 2013, 26,491 drivers or passengers and 5,552 pedestrians or cyclists died in traffic crashes (NHTSA, 2014). While many of these injuries and deaths are attributable to individual error, some are due to unsafe road conditions, including roadway design, maintenance, and such features as lighting and crosswalks. A study by the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) found that 16.3 percent of motor vehicle crashes involved at least one roadway-related factor—roadway condition, view obstruction, geometry of the road, narrow shoulder or road, or missing traffic signs (NHTSA, 2008). Another NHTSA study found that 24 percent of nonfatal pedestrian injuries were due to tripping on cracked or uneven sidewalks, and 13 percent of nonfatal cyclist injuries occurred because the roadway was not in good repair (NHTSA, 2012). Pedestrian safety can be improved not only by maintaining sidewalks but also by using crosswalks with traffic signals, raised medians, and traffic-calming measures such as curb extensions and lane reductions (FHWA, 2005). In short, the condition and design of a community’s roads can contribute greatly to the safety and well-being of its residents.

Hazard Risk

The natural and built features of a community can dramatically affect its ability to withstand and recover from disasters. Natural protective land features such as sand dunes, wetlands, and barrier islands can blunt the impact of a storm or hurricane and protect inland areas from flooding and damage. The design of the built environment—including homes, buildings, and infrastructure—is a critical factor in the health and safety of residents during and after a disaster. It has been said that “earthquakes don’t kill people—buildings do” (FEMA, 2014a). Residences and buildings that are well built and well maintained can help keep residents safe from seismic activity, fire, flooding, and strong winds. In addition, if facilities such as water treatment and power plants are not sufficiently disaster-resilient, the loss of these critical services can make disaster response and recovery even more difficult. For example, millions of residents in New York City lost power during Hurricane Sandy as a result of storm-related damage and flooding. Many residents—including those in the city’s public housing—were without power for more than 2 weeks, during which time they lacked electricity for such essentials as heat and medical devices (Rexrode and Dobnik, 2012).

Health Disparities

Health disparities are “preventable differences in the burden of disease, injury, violence, or opportunities to achieve optimal health that are experienced by socially disadvantaged populations” (CDC, 2013a). Socially disadvantaged populations—such as those of lower socioeconomic status or racial minorities—bear a disproportionate burden of disease and death. African Americans, for example, have higher rates of premature death, infant mortality, obesity, and homicide than their white counterparts, and poor people are

more likely to suffer from asthma, diabetes, and poor self-rated health (CDC, 2013c). These disparities are due in part to differences in the communities in which people live (LaVeist et al., 2011). Neighborhoods populated primarily by racial minorities and/or low-income families are less likely to have a retail outlet offering healthy food (Grimm et al., 2013), more likely to be in close proximity to a highway (and thus pollution) (Boehmer et al., 2013), less likely to have access to recreational facilities (Gordon-Larsen et al., 2006), and more likely to have high rates of street violence (Prevention Institute, 2011). These neighborhoods also have less access to health and other essential services, and their housing, infrastructure, and roads may be poorly built or maintained.

By almost every measure, neighborhoods with concentrations of low-income people and racial minorities tend to be less conducive to health than other neighborhoods, and this difference is exhibited in the disparities in their health outcomes. Babies born in the suburbs of Maryland and Virginia have a life expectancy 6 to 7 years longer than those born a few miles away in Washington, DC (RWJF, 2014). Children who live in low-income urban neighborhoods are more likely to suffer from asthma than their counterparts in bordering neighborhoods (Olmedo et al., 2011). These health disparities might be diminished by efforts to change the environment of the neighborhood through policies designed to improve housing, transit, infrastructure, sources of pollution, and access to healthy food and health care (Lee and Rubin, 2007).

A Systems Approach for Health Improvement

While the natural and built environments have direct effects on population health and the social determinants of health, it is important to consider the socioeconomic systems that operate within those environments. There are obvious relationships between the shape, pattern, and composition of physical environmental features and socioeconomic systems. When it is necessary to rebuild or repair a community’s physical infrastructure, including residences and businesses, it makes sense to do so in concert with strategies addressing the services and systems that operate there. In New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina, for example, major repairs were needed for many features of the health care infrastructure. In light of more serious underlying problems represented by low metrics of population health, however, the community and its health care leadership fashioned a whole new approach, a reconfiguration of the entire system, instead of simply rebuilding those buildings that had been damaged by the storm and subsequent flooding. Thus, physical environments and human systems within those environments determine success in striving for a healthy community.

Well-being is a general metric of how well the community functions, how smoothly its systems perform. Social and health disparities typically arise when system performance wanes or, rarely, in the event of a disaster. Significantly, many federal and other government programs address issues of socioeconomic system failure. Those same programs, to varying degrees, are forced into “overdrive” when a disaster strikes—old problems are exacerbated and new problems arise. One example concerns crime, especially violent crime that has a severe negative effect on health. A contributor to crime is poor community design. A partial remedy for crime is to design streets, sidewalks, businesses, and housing to incorporate impediments to criminal behavior and to increase social observance of public places through increased social activity and stronger social capital. Also needed, however, is attention to crime prevention systems such as crime analysis, effective policing, and new inducements for those who may be inclined to pursue crime. Obvious linkages are education, employment, poverty, behavioral health, and a variety of social service initiatives pertaining to substance abuse, teen pregnancy, gambling addiction, and early childhood development. In this context, it is not sufficient simply to restore the community to its prior state after a disaster. Achieving a safe environment promises major co-benefits for health, especially for vulnerable populations.

These relationships are crucially important after a disaster, and they affect the pace of recovery because these fundamental risks in society’s systems are ever present, but they are stressed and exacerbated by a disaster. The committee heard testimony, for example, on the toxic effect of temporary housing on children as a result of relocation, change of schools, and other disruptions (Redlener, 2014). Restoring the natural and built environments after a disaster is an important step, but attention must also be paid to

system weaknesses. Importantly, this is a challenge already well recognized because communities of all sizes must wrestle with the high cost of servicing neighborhoods dominated by disparities in the socioeconomic system. Addressing blight, poverty, low educational attainment, commercial decline, joblessness, and the full range of negative influences from deteriorated housing is the mission of community development (supported in part by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development’s [HUD’s] Community Development Block Grant). Communities with experience in system remedies are well suited to bridging the gap between concerns for the natural and the built environment and the social and economic functions within those environments.

Box 9-2 highlights a real-world example of a community using this type of systems planning in its disaster recovery. Springfield, Massachusetts, came together as a community following a tornado in 2011 that destroyed areas of the city and used a “nexus” framework for an integrated approach to recovery project planning. Since creating the plan and executing the plan are fundamentally different and also can be separated by a period of months or even years, it will be important to monitor how Springfield’s plan becomes operational to see whether the community’s needs are truly met when competing financial priorities arise. Coordinated implementation of the plan elements is necessary so that each element is not implemented as an individual project, which could lead to inefficiencies and gaps in execution.

Contemporary Approaches to Healthier and More Resilient and Sustainable Communities

Revisiting the “duality of use” concept, many agencies and organizations outside the health sector also are thinking about sustainable, long-term planning for communities. As it happens, many of the smart growth strategies recommended by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) for achieving sustainability also can have positive impacts on community health as well as mitigate the impacts of a disaster.

As discussed earlier, environmental quality has both direct and indirect effects on population health. Major improvements in water quality in the nation’s streams and lakes have been made since the 1970s. Planning for better infrastructure for wastewater treatment has lowered concentrations of toxic material. In some extreme cases—such as Love Canal in New York and Times Beach in Missouri—homes have been relocated away from hazards because of explicit health risks. Community plans also have become more health conscious. Transportation planning has integrated measures of environmental effects on the population, including emissions, noise, safety, and elements that facilitate pedestrian and bicycle travel for both recreational and commuting trips. Themes such as smart growth represent an attempt to balance social and economic objectives. EPA’s report on creating equitable, healthy, and sustainable communities describes smart growth as “a range of strategies for planning and building cities, suburbs, and small towns in ways that protect the environment and public health, support economic development, and strengthen communities” (EPA, 2013, p. 4). The Partnership for Sustainable Communities, an initiative of the U.S. Department of Transportation (DOT), HUD, and EPA, is the centerpiece of the nation’s new approach (DOT et al., 2014), empowered by three factors: (1) coordinated financing, (2) planning mandates, and (3) technical assistance. While this notion of development and interaction with the environment goes back decades, new ways of incorporating sustainable strategies and elements into homes, public centers, parks, and other sections of a community have increased in recent years.

Accompanying this shift is guidance and renewed energy from EPA and such groups as the Partnership for Sustainable Communities and the American Society of Landscape Architects. In 2009, through a partnership with local government councils, EPA developed smart growth guidelines for sustainable design and development for communities striving to achieve future growth that results in stronger neighborhoods, protected open space and watersheds, and healthier and more affordable homes (EPA, 2009). These strategies, coupled with “green” initiatives—environmentally friendly approaches that can range from building practices to product labeling to chemical engineering—can lead to a more resilient, sustainable community. These practices, although created with sustainability in mind, can have an impact on the health of a population. For example, people in communities with abundant green space tend to be healthier (Maas et al., 2006). Cities incorporating green infrastructure into their planning often find

BOX 9-2

Building the Community Nexus

Significant social and financial costs are associated with siloed approaches to community planning and the resultant inefficiency. For communities looking to design a more collaborative and systematic approach, particularly in the process of rebuilding following a disaster, the “nexus” concept may serve as a guideline for meeting the comprehensive needs of community members. These needs, which include a community’s most crucial quality-of-life resources, fall into six domains:

- the physical domain, which includes a community’s built and natural resources;

- the cultural domain, which includes those aspects of a community related to individual and collective values;

- the social domain, which governs well-being and includes a community’s health and human services;

- the economic domain, which works to maintain a healthy balance among a community’s financial, human, and environmental capital;

- the organizational domain, which encompasses programs and services such as community clubs, civic societies, and city and county school boards and councils; and

- the educational domain, which covers the span from early childhood education to college, as well as workforce training programs.

It is the nexus of interactions among these domains that will best serve to promote a community’s overall wellbeing and health.

The nexus planning framework is a highly integrated model in which a nexus of planning exists for the people, programs, and places involved in the provision of public services and programs. A fully developed nexus site will serve as the place where a variety of community services and amenities—such as grocery stores, farmer’s markets, parks, libraries, child care centers, and schools—are situated, coordinated, and administered to best address and serve the needs of the community. Importantly, the approach transcends physical design,

that the environmental benefits justify the up-front costs and are worthwhile for day-to-day needs, such as by reducing energy use, filtering air and water pollutants, and preserving wildlife habitats. Preserving habitats to ensure healthy ecosystem functioning can have a positive impact on the dense urban and suburban environments in which more than 80 percent of the U.S. population lives (USDA, 2014). For those concerned about hazard mitigation and resiliency, such strategies as green roofs, rain gardens, and porous concrete can help manage stormwater runoff, alleviate flooding, and prevent aquifer pollution after a hurricane or other disaster.

Again, however, many of these ideas are attractive in theory and in the planning stages, but they are sometimes challenging to execute. To overcome such barriers, federal agencies are using programmatic incentives to drive sustainable change in communities that aligns with national strategic priorities. Leadership in Energy & Environmental Design (LEED) for Neighborhood Development (LEED-ND), for example, is “a rating system that incorporates principles of smart growth, New Urbanism, and green building into a voluntary framework for sustainable neighborhood planning and design” (HUD, 2012). To incentivize the use of this framework, “HUD recently incorporated LEED-ND into all of its grant funding through the General Section and required LEED-ND certification for Choice Neighborhoods Planning Grant recipients” (HUD, 2012). Other federal support and community grants with this type of focus on green development and smart growth strategies can help communities manage hazards in a cost-effective way while realizing other benefits for social and physical well-being.

and also integrates program design and policy tools. For example, joint use agreements can expand access to amenities by enabling the community to use school facilities such as gyms, auditoriums, and libraries during evenings and weekends. The result is not only a more sustainable community but also a more equitable one—vehicle ownership is no longer a prerequisite for accessing community amenities and services. The opportunity for increased physical activity benefits all community members.

In Springfield, Massachusetts, redevelopment under a nexus framework is under way in response to a devastating tornado that tore through the city on June 1, 2011. In the aftermath of this disaster, citizens came together to develop a community-driven plan called Rebuild Springfield, with both residents and stakeholders working collaboratively inside the nexus framework. Among the recommendations prioritized as part of this plan is putting schools and libraries at the center of a nexus approach to provide a wide range of community services and programs. One proposed approach for catalyzing this process is the development of partnerships between public library branches and educational institutions.

Springfield has been designated as a “Gateway City,” a title given to formerly thriving industrial cities now showing promise as regional economic and cultural centers. Many recommendations of the Rebuild Springfield plan take into account and celebrate Springfield’s cultural diversity. The redevelopment proposal emphasizes the need to better connect the community, both physically and culturally. This will be accomplished with improved transportation systems, as well as efforts to increase access to cultural amenities through coordinated outreach.

Rebuild Springfield represents a unique example of a planning project developed entirely around the nexus framework and domains. While implementation of Springfield’s plan is still in progress, there are numerous examples of completed nexus sites whose positive impact on their communities can already be observed. In Houston, Texas, the Baker-Ripley Neighborhood Center was completed in 2010 and serves as a true neighborhood nexus site. The center includes an elementary school, a public library, a farmer’s market, parks, business facilities, and a community health center. Since its completion, the center has become a vibrant community hub, providing a vast number of services for a previously underserved community.

SOURCES: Bingler, 2011, 2014; Springfield Redevelopment Authority, 2012.

DISASTER IMPACTS ON COMMUNITY SYSTEMS: IMPLICATIONS FOR HEALTH AND RECOVERY

Following a disaster, the short-term impacts on community systems and overall health generally are well known, often receiving significant media coverage. Initial concerns include impeded access to goods and services—including food and supplies and ambulance services—because of impassable roads or nonfunctioning transit. Another concern is impaired functioning of critical infrastructure that provides clean water to the community and power to important buildings such as hospitals. Environmental degradation that can exacerbate existing conditions (e.g., asthma) or cause new ones may be less apparent in the immediate aftermath of a disaster. After Hurricane Sandy, for example, “Floodwaters, massive storm runoff, wind damage, and loss of electricity combined to cause wastewater treatment plants up and down the mid-Atlantic coast to fail. These failures sent billions of gallons of raw and partially treated sewage into the region’s waterways, impacting public health, aquatic habitats, and resources” (Hurricane Sandy Rebuilding Task Force, 2013, p. 27).

By the time long-term disaster impacts start to manifest in a community, the media cameras usually are long gone, and many downstream consequences go unnoticed until the situation reaches a threshold. Occasionally, commercial buildings or housing projects are too damaged to be repaired easily, so they are abandoned or shifted further down the priority list. The result can be an increase in blight and associated crime, causing the community to break up and individuals to scatter across a state or region. Positive health effects of the social capital that existed in the neighborhood may be at risk. Because disasters often cause disproportionate hardship for vulnerable populations and low-income neighborhoods, recovery planning

requires careful demographic analysis. Post-disaster reconstruction and relocations are steep hurdles for individuals and families. Upgraded construction codes, mitigation requirements, and changes in actuarial insurance rates are major challenges for elderly and fixed-income individuals, for example. Neighborhood changes and the loss of hospitals, physicians, grocery stores, and pharmacies can exacerbate the hardships faced by residents even if temporary housing is provided. Rarely do recovery plans address all of these needs, nor can restoration of full community services be accomplished immediately, leaving the population in dire straits at a time when all forms of stress and uncertainty are at their highest levels. This is an important unmet need. If a family is displaced from its affordable housing but wants to stay in the community, there may be limited options for doing so. All of these scenarios lead to further deterioration of the social determinants of health.

It is possible to overcome these challenges, although as Robert Olshansky from the University of Illinois testified to the committee, intensive planning is required to rebuild a city successfully after a disaster (Olshansky, 2014). Building a city under normal circumstances is highly complex, with many different actors involved. Added complexity arises during disaster recovery as a result of the compression of time in which the same set of tasks must be accomplished. Despite the added challenges, this planning process should be guided by a shared goal of helping people create settlements that are healthy and safe places to live that provide viable livelihoods, and that enable convenient access to all of the things they need. Sudden loss creates opportunities for reorganizing the elements of a community—not just facilities, but also services. As discussed earlier, disaster-related challenges provide an opportunity to approach community redevelopment in ways that improve health and social well-being. It is important to note, however, that the extent of need and opportunities for community redevelopment will depend on the pattern and extent of the damage caused by a disaster. Every disaster may not present the opportunity to revamp the community or undertake long-term planning. For example, tornados usually leave the foundations or basements of buildings intact, so the most economical solution often is to build on the preexisting base, keeping the same footprint.

ORGANIZATIONAL STRUCTURES AND RESOURCES FOR HEALTHY COMMUNITY PLANNING AND REDEVELOPMENT

In steady-state times, a number of federal agencies provide funding and technical assistance to support the development of the built and natural environments. A comprehensive review of these resources is beyond the scope of this report, but the relevant agencies and funding sources related to community development and rebuilding are briefly reviewed here. As mentioned earlier, the major federal agencies whose policies and funding shape the built and natural environments in the United States came together in 2009 to form the Partnership for Sustainable Communities. Through the efforts of DOT, HUD, and the EPA, “more than 1,000 communities in all 50 states, Washington, D.C., and Puerto Rico have received more than $4 billion in grants and technical assistance to help them grow and improve their quality of life” (DOT et al., 2014, p. 2).

Individually, the agencies within the partnership also are major funding sources for sustainable community building. DOT offers the Transportation Investment Generating Economic Recovery (TIGER) Discretionary Grant program that enables applicants to invest in road, rail, transit, or port projects. Applicants must describe the benefits of their proposed project for “five long-term outcomes: safety, economic competitiveness, state of good repair, livability and environmental sustainability” (DOT, 2015).

In response to community demands from around the country, EPA’s Office of Sustainable Communities launched the Building Blocks for Sustainable Communities Program. This program offers targeted technical assistance to selected communities using tools that already have demonstrated widespread results.

________________

2 A broader synopsis of legislation and federal policy related to disaster recovery and health security can be found in Appendix A.

To illustrate some of the topic areas within the program, the topics highlighted for the 2015 program are listed below, showing overlap among sustainable objectives for cities, hazard mitigation needs, and healthy community elements:

- bikeshare planning,

- supporting equitable development,

- infill development for distressed cities,

- sustainable strategies for small cities and rural areas, and

- flood resilience for riverine and coastal communities (EPA, 2014).

HUD offers the Community Development Block Grant (CDBG) program, alluded to earlier, which provides funds for addressing a wide range of community needs. Specifically, grantees must use at least 70 percent of the funding for projects directed at low- or moderate-income populations and encourage citizen participation (HUD, 2015). The program provides annual funding to state and local entities, but it also is flexible enough to provide assistance following a presidentially declared disaster, subject to the availability of a congressional supplemental appropriation.

HHS also has a role in healthy community development. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC’s) Built Environment and Health Initiative (also known as the Healthy Community Design Initiative) works to improve community design decisions by linking them with public health surveillance, utilizing such tools as the health impact assessment (HIA), building partnerships with key decision makers in the community, and conducting research and translating its results into best practices. The initiative funded and supported 34 HIAs in 2011 and continued to fund 6 local, county, and state entities’ HIAs from 2011 to 2014. Data from the HIAs have been used to develop health-focused frameworks in communities in Nebraska, North Carolina, and Oregon (CDC, 2013b). Additionally, the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) authorized the Community Transformation Grant Program through the CDC, aimed at helping communities design changes to their built and social environments to address chronic diseases3 (CDC, 2014b).

After a disaster, a number of different federal funding mechanisms come into play. When a disaster exceeds the capacity of the state or locality to respond, a presidential disaster declaration can bring in federal aid under the Robert T. Stafford Disaster Relief and Emergency Assistance Act4 (CRS, 2014; see also Chapter 4). The National Disaster Recovery Framework (NDRF, described in detail in Chapter 3), serves as a conceptual guide for recovery planning at all levels of government and is intended to improve coordination of federal recovery resources (FEMA, 2014b). Similar to the Emergency Support Functions (ESFs) of the National Response Framework (NRF), the NDRF introduces six Recovery Support Functions (RSFs), each designated to a different lead federal agency:

- Community Planning and Capacity Building—Federal Emergency Management Agency,

- Economic—U.S. Department of Commerce,

- Health and Social Services—U.S. Department of Health and Human Services,

- Housing—U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development,

- Infrastructure Systems (including transportation) —U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, and

- Natural and Cultural Resources—U.S. Department of the Interior (FEMA, 2014b).

Under the NDRF, a FEMA official functions as the federal disaster recovery coordinator and for presidentially declared disasters, FEMA also provides public assistance and hazard mitigation funding for repair and restoration of public (and some nonprofit) infrastructure where needed. Although HUD leads

________________

3 Funding for the Community Transformation Grant Program was eliminated by Congress in the Fiscal Year 2014 Omnibus package.

4 42 U.S.C. § 5121 et seq.

the Housing RSF, it is also an important funder for major disasters if Congress makes a supplemental appropriation through HUD’s CDBG program for Disaster Recovery (CDBG-DR) as a vehicle to aid rebuilding efforts and to provide the start-up funds necessary to initiate the recovery process. Since such funding may support a wide range of recovery activities, it enables HUD to better assist communities that otherwise might not recover because of limited resources and to prevent them from experiencing the long-term health impacts discussed previously (HUD, 2014). However, as discussed in Chapter 3, HUD’s community development function has not adequately been integrated into the NDRF.

The framework aspires to better utilization of existing resources; however, it does not yet clearly capture the contemporary healthy community and sustainable development practices that are being led by CDC and the Partnership for Sustainable Communities. As discussed in Chapter 3, the NDRF needs to be upgraded to reflect these prior achievements and their relevance to disaster circumstances. Combined, these additional themes of integration and transformation could foster a major advance in the nation’s capacity for disaster recovery.

As discussed in Chapter 3, states and regional entities have key roles in recovery, and in many cases, they are the grantees for federal grant programs in the case of a presidentially declared disaster. State emergency management agencies, for example, are the grantees for FEMA Public Assistance and Hazard Mitigation Grant Programs, and they must work closely with community planning entities to manage mitigation activities. For optimal vertical integration, state agencies need to align with the NDRF structure and, in doing so, should ensure that their state-level entities with everyday responsibilities for urban or regional planning and development are incorporated into the RSF structure and understand their roles. For long-range transportation planning, for example, there are transportation planning and policy assets and personnel at both state and regional levels that need to be incorporated into long-term recovery planning following a disaster to see projects through to fruition. The state should not rely on the emergency operations personnel that may have represented that sector during the immediate response to fulfill an ESF.

In contrast to the strong state-local relationships designed into financial, technical, and operational systems funded by DOT, HUD, and EPA for steady-state community planning, disaster recovery is a process that often reveals a mismatch between state and municipal governments. Because of the infrequency of disaster occurrences and the absence of strong policy foundations, states, cities, and counties do not have regular opportunities to share information or practice how to address recovery issues that arise during disasters. Strategies of redevelopment, economic incentives, and neighborhood revitalization are inherently in the municipal domain and may not be well understood by state agency personnel. After Hurricanes Katrina, Rita and Ike, both Louisiana and Texas experienced tumultuous reorganizations of their disaster recovery programs midstream, with legislative and media investigations of disharmony (Kirkland, 2012). States need to organize and align their RSF structure with both the national and the local level to ensure that events from past disasters are not repeated.

Since some planning—particularly for transportation and economic development—takes place primarily at the regional (substate) level, it is important for those organizations to be included in the development of recovery plans, especially as their functions may align with the NDRF structure. Metropolitan planning organizations (MPOs) play a large role in organizing and executing transportation planning throughout a defined urban area of one or more counties and sometimes a multistate region. Since they already exist, with defined leadership, processes, and networks, they often can play an important role in making recovery decisions for transportation- and development-related issues. In Washington’s Puget Sound region, for example, the 2014 Transportation Recovery Annex recommends including MPOs in a transportation stakeholder forum for the development of regional transportation recovery policies (Washington Emergency Management Division, 2014). Because the Economic Development Administration serves as the coordinating agency for the Economic RSF (EDA, 2015), organizing the regional economic development districts to align with the NDRF structure also can facilitate the recovery process for a community. By

becoming involved in recovery at the regional level, the economic development districts can provide important on-the-ground knowledge and awareness to the federal RSF lead and ensure that national recovery decisions are being made with the most accurate economic information available.

Comprehensive plans created at the local level drive land use policy and community investments in infrastructure, but different locally derived structures for developing and implementing policies for health exist across the country. In Pinellas County, Florida, for example, the health department is actively engaged with other departments in addressing the needs of blighted and deteriorated neighborhoods, followed by redevelopment with new, safe construction enabled by HUD grants and interagency collaboration. King County in Washington is taking a similar approach through its Communities of Opportunity program (see Box 2-8 in Chapter 2). Yet there are virtually no known research cases that address how this kind of demonstrated capacity of health and social service agencies at the local level to achieve high levels of collaboration around development policies translates to better post-disaster recovery. It is reasonable to assume that this approach can offer distinct advantages and that better plans will result when health, medical, and social services are viewed holistically among themselves and with other community policies of a recovery plan.

Like state and regional entities, local government agencies need to align with the NDRF structure and appoint or identify representatives to coordinate with their state, regional, and federal counterparts. Such arrangements should be put in place before a disaster. While recommendations and guidelines may come from the state or national level, ultimately it is often up to the local government to decide how to reinvest in its community. As discussed throughout this chapter, there are many ways to leverage strategies and the energy and interest of community leaders to bring about positive change at the local level.

Nonprofits, Philanthropies, and the Private Sector

Nonprofit organizations and businesses have a vested interest in rebuilding in the communities in which they work and with which they feel a connection, and therefore, they also should be included in discussions at the local government level to facilitate and execute recovery planning. Philanthropies can be important funders for redevelopment to address the needs of underserved populations, especially those groups, such as the Rockefeller Foundation and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, that support resilience building and improvement of the social determinants of health in their day-to-day work. Following a disaster, having their added funding along with expertise in focusing health interventions on vulnerable populations also can aid in long-term recovery. After a disaster, nonprofit organizations such as Architecture for Humanity provide pro bono design services through their membership. These groups need to be engaged proactively in recovery planning to ensure that recovery activities are seamless across the spectrum of a community.

Nonprofit institutions and the private sector also can play a role in financing recovery and supporting public health outcomes. The Reinvestment Fund is a Community Development Financial Institution (CDFI) that serves people who might otherwise be disconnected from the credit system (TRF, 2015). CDFIs use federal resources, such as incentives, tax credits, and bond guarantees, to serve low-income people and communities that lack access to affordable financial services and products (U.S. Department of the Treasury, 2014). This sector also is experiencing a change in focus, with increased awareness of the nexus between healthy and productive communities. In recognition of this nexus, one nonprofit CDFI, the Low Income Investment Fund, has been taking a more holistic approach that involves not only building affordable housing in a neighborhood but also building and supporting high-performing schools, health clinics, and recreational facilities with access to public transit (IOM, 2014b). While some might be skeptical that larger banking institutions would invest in these kinds of community development projects, the Commu-

nity Reinvestment Act,5 passed in 1977, mandates that banks reinvest in low-income communities from which they take deposits. They are graded on their performance in this regard and so are incentivized to strive for higher rankings. Tax credit incentives through the New Markets Tax Credit also are spurring investors to revitalize impoverished areas. Established as part of the Community Renewal Tax Relief Act of 2000,6 it has helped jump-start community development and is used to capitalize lending institutions that finance small businesses and help address the social determinants of health in low-income neighborhoods (Erickson and Andrews, 2011).

Collaboration and Coordination

During steady-state periods, mechanisms for collaboration and coordination are necessary because of the interconnected nature of the various facets of community planning (e.g., land use and transportation). These mechanisms are essentially systematic arrangements for professional teams and advisory groups to carry out analysis and program development that includes plans, projects, and budgets. Some groups, such as MPOs, are more familiar and comfortable with working together than others because they operate together routinely. For others, it is important to assess the ability to work together on short notice in the event of a disaster demanding multisector recovery planning. Such an assessment needs to consider the ability to collaborate across sectors and whether the partners are familiar with each other’s language and terminology. With the emergence of many new opportunities for partnerships with the health sector, the question arises of what collaboration among various sectors would look like. In a 2013 study conducted for the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation’s Commission to Build a Healthier America, the researchers wanted to measure the degree to which cross-sector collaboration occurs between health and other sectors, whether such collaborations have positive effects, and what the indicators of positive collaboration are (Mattessich and Rausch, 2013). They report that respondents frequently cited major benefits of collaboration such as pooling resources and dividing risk. They also note that skilled leadership was identified as one of the top three factors for a successful collaboration, yet at the national level, no single formal network exists to unify this newly emerging field of cross-sector collaboration aimed at improving health (Mattessich and Rausch, 2013). Finally, they emphasize the importance of “building the evidence base for cross-sector initiatives that effectively improve health by creating environments that protect and actively promote health” (Mattessich and Rausch, 2013, p. 10). Determining how to acquire and share the evidence needed to make the case for joint investments can make partnerships between the health sector and entities involved in the design of the physical environment even more attractive and widespread. If such integrated initiatives can be shown to save medical costs downstream, health management and affordable care organizations may have an even greater incentive to collaborate (Erickson and Andrews, 2011). New networks can create an opportunity for breaking down siloes to achieve shared goals across sectors. Opportunities for such collaborations are discussed in the sections below.

Planning and Design

Although community planning as a field was created in large part in response to public health needs (e.g., addressing sanitation issues), the fields of public health and planning have since diverged. There is growing recognition, however, that these two sectors cannot continue to operate in isolation (Ricklin et al., 2012). Health concerns increasingly are falling within the scope of planning departments, and the public health field has discovered the power of comprehensive plans, social capital and cohesion, and other planning tools for altering the physical and social environments that impact health. As discussed earlier in this chapter, decisions being made about community design, land use, and transportation are

________________

5 Community Reinvestment Act of 1977, Public Law 95-128, 91 Stat. 1147, Title VIII of the Housing and Community Development Act of 1977, 12 U.S.C. § 2901 et seq.

6 Community Renewal Tax Relief Act of 2000, incorporated into Public Law 106-554.

having effects on air and water quality, physical activity, exposure to contaminated industrial sites, and other important determinants of health.

Recognizing this linkage, New York City established a working group in 2010 comprising design organizations; academics; and city agencies involved in health, city planning, transportation, and construction. The group was tasked with developing Active Design Guidelines—“evidence-based and best-practice strategies for increasing physical activity in the design and construction of neighborhoods, streets, and buildings” (Lee, 2012, p. 5). Likewise, the American Institute of Architects has established a New Design and Health Agenda, and in 2014 it held a summit focusing on how public health officials and designers can intersect (AIA, 2014). Planners are beginning to understand the impact they can have on public health, and some public health departments are even hiring planning professionals to advise communities on healthy designs. Likewise, planners would benefit from data and metrics that are available to public health departments to understand where interventions would best be implemented. A recent example of such partnerships is King County Board of Health’s adoption of “Planning for Healthy Communities” guidelines in 2011. These guidelines are intended to inform land use and transportation planners about strategies that could have an effect on all residents of King County, Washington, based on actual causes of death and illness (King County, 2011).

Community Development Entities

Recent years also have seen increased collaboration between the community development sector and the public health sector as greater understanding of their shared goals reveals opportunities to coordinate or combine their individual funding streams. As with the planning and green infrastructure sector, community development entities are realizing that the benefits of their efforts extend to health. At an Institute of Medicine (IOM) workshop on financing population health, Raphael Bostic, the Judith and John Bedrosian Chair in Governance and the Public Enterprise at the Sol Price School of Public Policy, University of Southern California, said he believes a reset is occurring in the way people think about community development and population health (IOM, 2014b). He attributed this reset in part to demonstration projects in the housing and urban development sectors revealing the largest effect on health benefits:

For example, the Moving to Opportunity program, in which low-income families were given vouchers that enabled them to move out of areas with concentrated poverty, produced marked improvements in stress-related outcomes, depression, obesity, and diabetes. “That was a wake-up call,” Bostic said. “When the demonstration started, health was not even on the radar screen.” (IOM, 2014b, p. 27)

Erickson and Andrews (2011) also argue that through the ACA, federally qualified health centers should coordinate more closely with community development entities. If medical clinics were able to connect more easily and seamlessly with a network with existing links to funders, social services, and other community organizations, divisions between sectors could be further broken down.

The increased awareness of shared goals between the community development and health sectors is encouraging but represents only a first step. The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation’s Commission to Build a Healthier America recommends that the United States fundamentally change its approach to revitalizing neighborhoods by fully integrating health into community development (RWJF, 2014). By extending the concept of “health” into the neighborhoods where people live, play, and work, both sectors can think more broadly about potential interventions and desired outcomes to build healthier communities.

Transportation

Transportation has long been associated with public health with respect to prevention of injuries related to vehicle crashes and safety laws such as those mandating the use of seatbelts. However, DOT and the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) also have been involved in policies related to health,

and increasingly are regarding healthy outcomes as an important part of their objective in creating livable, sustainable communities. In 2012, they created a Health in Transportation Working Group to examine their policies and regulations on health issues, as well as ways to incorporate health into transportation planning and educate both internal and external stakeholders (FHWA, 2015).

Awareness of this connection occurred at the state level in Massachusetts. In 2009, a strong transportation reform law designed to consolidate disparate services in the state led to the development of the Healthy Transportation Compact, an interagency group chaired by the secretary of transportation and secretary of health and human services at the state level. Its goal is to collaborate on the potential health effects of transportation decisions. Examples of the group’s initiatives include:

- Mass in Motion Program (a statewide program that promotes opportunities for active living);

- Municipal Wellness Grants (distributed at the local level so communities can increase opportunities and customize initiatives to their needs); and

- Safe Routes to School (which promotes healthy alternatives for children to travel to school) (IOM, 2014a).

Creating a Healthy Community Vision for Recovery

Prior to a disaster, when there is time to think through priorities, leaders can take various actions to create and promote a healthy vision for recovery should a disaster strike. Holding community planning and visioning workshops—also called charrettes—is a good way to obtain input from residents with which to prioritize needed actions, and it also can secure buy-in for projects or developments. Such visioning exercises may have been conducted in the past, either as a coordinated effort or by separate groups. As discussed in Chapter 3, building on these efforts and being as inclusive as possible can ensure less push-back by those who contributed previously and may shorten the timeline for action if work has already been done or processes designed.

In these efforts, it is important to engage the health sector. The health sector is a source of data and information that may be difficult to find elsewhere (e.g., from community health assessments); it has connections with various community networks; and it brings a different perspective on strategies for building stronger communities. The vision and goals created from these workshops should be incorporated into the overall comprehensive plan for a town or city, as discussed in Chapter 3.

Organizing for Disaster Recovery Planning

Each sector has its own roles and responsibilities in recovery planning that need to be laid out, but a forum also is needed to identify and create synergy among the various projects and programs being planned. There may often be overlap or shared goals across projects within a community, and being aware of those projects and their goals before a disaster will facilitate streamlining recovery in a coordinated manner should such an event occur. It is difficult to plan what every sector’s actions will be during pre-event recovery planning, since most communities are at risk of several different types of disasters with varying impacts. Nonetheless, it is important to plan the operations and identify roles and contingencies. As part of its project to update its 1998 report, Planning for Post-Disaster Recovery, the American Planning Association created an annotated Model Pre-event Recovery Ordinance designed to guide communities in preparing prior to a disaster so they can better manage the recovery process. This guidance includes advising communities to create a recovery management organization prior to a disaster (APA, 2014a).

As discussed earlier, the representatives for the RSFs in community recovery will need to be different from those leading the ESFs. In some cases there may be some overlap but, generally, different expertise is needed to address long-term needs versus those associated with the emergency response. As discussed

in Chapter 3, jurisdictions need to leverage existing community structures that promote an integrated approach. There is no value to building a new network of people and processes that will be used only in the aftermath of a disaster. Structures and networks already in place are familiar with their target audiences, stakeholders, and potential vendors and partners for rebuilding. After a tornado demolished much of Joplin, Missouri, in 2011, City Manager Mark Rohr attributed some of the success of the town’s recovery, including the development of the Citizens Advisory Recovery Team (CART), to activities initiated in 2001 to revitalize the downtown area. Rohr suggested that the community’s history of engagement in downtown revitalization served as a precursor to the CART’s mission to consider and outline a long-term disaster recovery strategy (Abramson and Culp, 2013). By building on a holistic vision, especially one already known and shared among stakeholders, sectors in a community can determine how they can best work together to realize that vision for their neighborhood, town, or city during recovery.

Conducting Vulnerability and Capacity Assessments

In addition to creating a vision for recovery and organizing sectors and stakeholders for recovery management, it is important for communities to conduct assessments of their vulnerable infrastructure, populations, and locations; take inventory of their assets; and understand their capacity limitations that would be stressed during the recovery process. For example, rebuilding and redevelopment will likely necessitate a massive amount of permitting so communities should assess in advance their capacity to meet this surge in need rapidly and smoothly. Capacity assessments of physical assets alone will be insufficient; the workforce needed to provide the increased services required after a disaster must also be assessed, and alternatives explored if it is inadequate. Having memorandums of understanding in place and processes for waiving regulations and collaborating across sectors prior to an event can facilitate recovery. Pinellas County, Florida, in its recent post-disaster redevelopment plan (PDRP), described its capacity assessment as follows:

The purpose of the Pinellas County Institutional Capacity Analysis is to examine the capacity of the county to facilitate redevelopment in the context of the goals and objectives of this plan. “Capacity” in the context of this plan is not focused on physical assets (i.e., number of fire trucks, ambulances, etc.). Instead, capacity is assessed to determine if the framework exists to implement the goals and actions in the PDRP, such as programs, agencies, organizations (and their associated staffs) and other tools. The assessment is intended to determine the robust programs and resources that strongly support post-disaster redevelopment, programs that exist but could be improved to better support post-disaster redevelopment goals, and the weakness or gaps where programs or plans could be implemented to improve the County’s capacity to recover in the long term. (Pinellas County, 2012, p. 4-55)

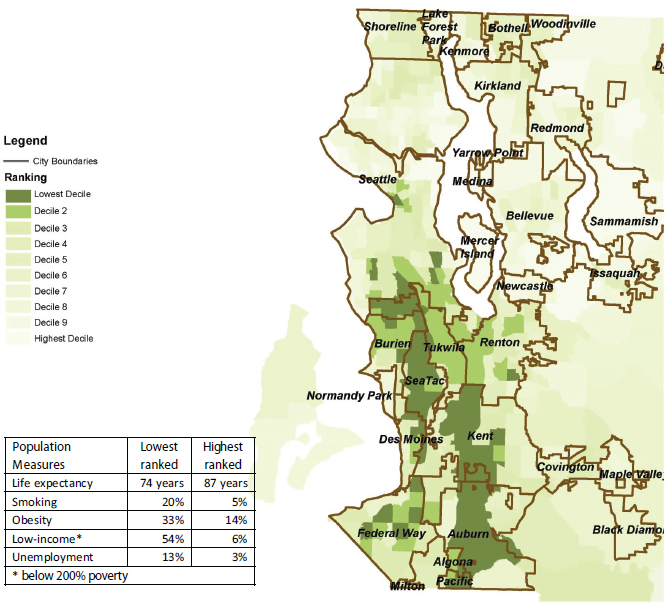

In addition to capacity, a strong understanding of a community’s vulnerabilities is needed to inform recovery planning. Although these kinds of analysis often focus on critical infrastructure, social vulnerability is increasingly being evaluated in the risk management process (see Chapter 2 for discussion on social vulnerability). The Pinellas County PDRP, for example, includes a socioeconomic profile (Pinellas County, 2012) as a component of its vulnerability assessment. Digital technologies are enabling emergency managers and health officials alike to identify areas with high social vulnerability. While geographic information systems (GIS) often are used in emergencies to map flood plains or key assets that can be deployed, they also can be used to map public health and social services data to show community and government officials where vulnerable neighborhoods may be following a disaster. In New Orleans, the health department, using data from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), created a map of residents who were oxygen dependent and would need immediate assistance in the case of lost power. The CMS data were found to be 93 percent accurate, giving the health department a clear picture to start with in the event of an emergency (DeSalvo et al., 2014). Similarly, King County, Washington, used GIS software to map socioeconomic factors in the county that are associated with health risks (see Figure 9-1). Such data are invaluable to the effective targeting of resources to areas of need after a disaster.

SOURCE: King County. 2014. Health and Human Services transformation plan and communities of opportunity. King County, Washington. Available at http://www.kingcounty.gov/exec/HHStransformation/coo.aspx.

EARLY POST-DISASTER RECOVERY PRIORITIES

The early recovery period often overlaps with and runs parallel to the disaster response phase. During this time, communities assess the extent of the disaster-related damage and begin restoration efforts. Although it is tempting to postpone considerations related to rebuilding in ways that support health, resilience, and sustainability, without these goals in mind, early restoration efforts may be undertaken in a manner that impedes future betterment opportunities.

Assessing Disaster Impacts on Community Systems

In the early stages of disaster recovery, it is important to conduct an impact assessment. This assessment will dictate what resources are needed, how the available funding will best be allocated, as well as

what players and stakeholders need to be engaged quickly. As mentioned previously, if a tornado destroys a neighborhood or private businesses, much of the recovery can be funded by private insurance, and a robust effort to overhaul the social fabric of a community will not be warranted. However, if public facilities are affected, infrastructure is destroyed past the point of repair, or an already declining area is heavily impacted, it will be necessary to assess the impacts quickly and facilitate the community’s transition from disaster response to disaster recovery planning—not waiting until the response ends to plan the recovery needs.

Restoring Critical Infrastructure and Remediating Immediate Health Threats

Following an impact assessment, early restoration operations needed for the short term, including those addressing infrastructure, land use, and environmental management, should be conducted. A comprehensive examination of the restoration phase of recovery is beyond the scope of this report, but the sections below highlight restoration needs related to protecting health.

Infrastructure and Transportation

In the initial phases of recovery, communities should address post-disaster challenges of transportation access in a prioritized manner. FEMA Public Assistance funds often cover emergency repair of public infrastructure and debris removal. However, debris removal can be a rate-limiting step for recovery activities and is critical to restoring access to goods and services that are essential to health. With the passage of the Sandy Recovery Improvement Act of 2013,7 FEMA developed a pilot program to incentivize rapid debris removal. Upon receiving a debris management plan prior to a declared disaster, FEMA will provide a one-time incentive of a 2 percent cost share adjustment for the first 90 days of debris removal activities, beginning the first day of the declared incident period, provided the plan is implemented for that disaster (FEMA, 2014c).

Selection of an appropriate site for dumping of debris is important to prevent potential health risks to nearby or future populations. Historically, careful site selection has not occurred, leading to issues of environmental justice (Allen, 2007). In light of the increased emphasis on green infrastructure and design discussed earlier in this chapter, a community also may want to consider a recycling program for debris, which could lessen the workload of disposal as well as contain costs. Through the FEMA pilot program, costs of sorting debris for a recycling program are eligible for reimbursement.

Reopening roads is another key recovery priority and can impact health. In setting criteria for reopening roads and restoring power, access roads to hospitals and other medical and ancillary facilities (e.g., pharmacies) should have priority. The need for alternative transit routes should be evaluated as well. If large temporary housing sites are set up in an area outside typical access routes, for example, community leaders may need to ensure that they are serviced by public transit so those temporarily displaced residents without access to personal vehicles can access essential goods and services as well as employment.

Another critical early priority is the restoration of utilities and communications systems. For example, water treatment facilities need to be up and running to prevent illness from contaminated water supplies and power is essential to health facilities and individuals requiring electricity-dependent medical equipment. Reestablishment of communication infrastructure is important for continued use of health information systems after a disaster, particularly for providers using cloud-based record storage. For those organizations that established backup measures in advance of the disaster (e.g., power generators, physical servers at nearby sites) as part of resilience-building efforts, such systems can be used until critical infrastructure is restored, thereby protecting against adverse health outcomes.

________________

7 Sandy Recovery Improvement Act of 2013, 113th Congress, H.R. 219 (January 29, 2013).

Land Use

Although there is often pressure to get a community “back to normal” after a disaster, it is important to discourage immediate rebuilding in potentially hazardous areas. A moratorium on immediate rebuilding may be the best option when there has been a great deal of destruction so that authorities and building owners can explore the advantages and disadvantages of rebuilding in the same location. Instituting a building moratorium also can prevent unscrupulous contractors who come into the affected community from taking advantage of people who have been traumatized and are willing to pay the first person who offers to help them get their home and life back. Following the Cedar Rapids, Iowa, floods in 2008, the city developed a model that required anyone doing repair or reconstruction in the city to first visit city hall and become certified as qualified and trustworthy (Schwab, 2014).

On the other hand, it is also important to examine options holistically and to consider the downstream effects a moratorium could have. Low-income housing often tends to be in vulnerable (e.g., low-lying) areas of a community. Delays in rebuilding public housing could add even more strain to parts of a community that are in great need (APA, 2014b). An extreme consequence could be increasing homelessness for residents and families who are unable to find affordable housing options. With this in mind, if a moratorium is deemed necessary while authorities examine mitigation strategies, particular attention should be given to temporary housing needs to ensure that vulnerable populations are provided for. (Temporary housing needs are explored in further detail in Chapter 10.) Many actions that should be taken at the local level are described in the American Planning Association’s model recovery ordinance described earlier in this chapter.

Environmental Management

Another early recovery priority is securing public sites contaminated with hazardous materials. It is important for municipal leadership to understand that this is a priority even if no immediate health effects are noticed. Following removal of hazardous materials, immediate environmental remediation should be executed to ensure that these materials do not pose a risk to the community in the months or years to follow.

The health promotion strategies discussed in this section are evidence-based but communities will need to determine what is appropriate to their local conditions and community vision. Communities should inventory their prior plans to identify opportunities to apply disaster-related resources to meet previously agreed-upon objectives. If those plans focus on safe access to healthy foods, for example, the recovery plan might include locating new or rebuilding retail grocery businesses or farmer’s markets in areas with demonstrated need. However, it is important to remember that the severity of the disaster may dictate what is possible with respect to strategies and desired outcomes of recovery. In cases of widespread damage, comprehensive initiatives such as mixed-use and transit-oriented development are possible, but if the impact is not as widespread and the corresponding recovery funding is more limited, smaller-scale initiatives, such as creating buffer areas around rivers, may be more practical.