2

Post-Disaster Opportunities to Advance Healthy, Resilient, and Sustainable Communities

A strong category 2 hurricane makes landfall on a small island in the Gulf Coast (NOAA, 2008). Winds estimated at more than 100 mph and a storm surge of more than 10 feet result in significant flooding and damage to the island’s physical infrastructure—more than 70 percent of the buildings on the island are damaged or destroyed, including large concentrations of public housing. Much of the island, including the interior of remaining homes and structures, is covered in a layer of sediment contaminated with heavy metals and other toxic residues from an industrial area that was in the path of the storm surge. Residents are displaced for weeks and in some neighborhoods, for months. Many never return. Those that do face enormous challenges. Many of the businesses that supported the economy of the island are closed for months, including the large academic center that represents the largest employer in the area. Jobs are lost as a result of these closures but also because parents are unable to find safe places to leave their children while they work. Most people are not adequately prepared to provide the documentation and paperwork (e.g., proof of home ownership, proof of insurance, medical prescriptions) needed to access critical benefits and resources. The local housing authority experiences a five-fold increase in demand for housing assistance (Nolen et al., 2010). The trauma and stress of this situation exact a toll on the health of the population, especially those with preexisting conditions such as chronic disease or mental illness. At the 1-year mark, more than 10 percent of the population meet criteria for a probable mental health disorder diagnosis (Ruggiero et al., 2012).

As the recovery process proceeds, it becomes clear that disadvantaged individuals and neighborhoods face additional challenges that delay recovery. Many of the most severely damaged neighborhoods are in low-lying areas of the island characterized by large concentrations of impoverished and low-income populations (Nolen et al., 2010). Disruption of public transit in these areas poses great challenges for residents that lack cars, a problem exacerbated by the closure of many neighborhood amenities such as grocery stores. A “not in my backyard” mentality impedes the timely rebuilding of public housing, which was torn down before former residents were allowed to retrieve any remaining belongings. Many former public housing occupants who have been unable to return to the island because of the lack of affordable housing have no voice in the recovery planning process as a result of restrictions that limit participation to current residents. Such cor-

rosive social dynamics build distrust among neighbors and further distress the vulnerable. Five years after the storm, public housing still has not been rebuilt (Rice, 2014).

The scenario above is not hypothetical, but describes the impact of Hurricane Ike on the island of Galveston, Texas, in 2008. This example demonstrates how disasters can alter the status of many of the fundamental elements that affect the health of a community—the availability of housing, including public housing for low-income individuals; social networks; environmental quality; economic stability and the availability of employment; transportation access to essential goods and services; safe places for children to play and learn; access to nutritious food; and continuity of medical care. Not only did the disaster add stress for already vulnerable populations and amplify existing health disparities; its effect on the population as a whole was to cause the long-standing suboptimal health of the community to deteriorate further. Even prior to Hurricane Ike, Galveston ranked below the Texas state and national averages with regard to such key health status indicators as mortality from cardiovascular disease, lung cancer, and suicide (GCHD, 2001).

For Galveston, and communities like it, recovery from a disaster can provide a mechanism for addressing many of the factors that contribute to poor health status and vulnerability. Disasters, although unquestionably tragic, create new resources and opportunities to advance the design and realization of healthy communities. One such opportunity is the synchronization of strategic planning across multiple disciplines and sectors that occurs during disaster recovery (Nolen, 2014), providing a mechanism for engaging the whole community in the redesign process. The sudden destruction of physical infrastructure and disruption of systems may in some cases enable significant reorganization of facilities, services, and organizational structures to create more optimal arrangements and dispense with obsolete ones that may have been impeding communities from reaching their full potential. Additionally, an array of resources, scaled appropriately to the nature of the event, are mobilized with the specific purpose of assisting communities in addressing many of the fundamental factors that are important to health, by, among other things,

- restoring public health, medical, and social service systems to meet the needs of the impacted populations;

- supporting safety, psychosocial well-being, and social connections; and

- rebuilding physical infrastructure such as housing, transportation systems, and critical public works systems.

It should be recognized, however, that there is no such thing as a blank slate after a disaster. To varying degrees, all communities are constantly amending their circumstances through a variety of programs and plans. A disaster is an influence on those ongoing practices, a temporary detour. The question becomes how to seize the opportunities of reinvestment to address long-standing and perplexing problems that compromise the health and overall welfare of a community.

Across the world, communities are already working to improve their own health status from the ground up by engaging community members and organizations in all aspects of projects, from setting initial priorities to evaluating outcomes—a phenomenon known as the healthy communities movement (Norris, 2013; Pittman, 2010). Acknowledging that the starting point for individual communities varies widely, the committee emphasizes that disaster recovery offers a unique opportunity to further these efforts. In this chapter, the committee outlines the elements of a healthy, resilient, and sustainable community and explains why an integrated approach is essential to enable the realization of that shared goal.

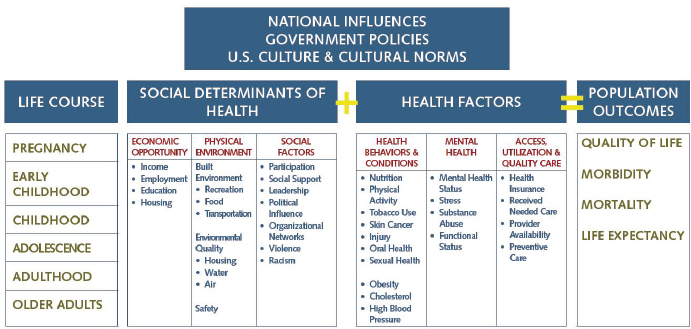

FIGURE 2-1 Model for the combinatorial effects of health determinants on population health outcomes.

SOURCE: Data provided by the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment, https://www.colorado.gov/pacific/sites/default/files/HealthEquityModel.pdf (accessed April, 4, 2015).

Leveraging the disaster recovery process to advance the health of a community necessitates an understanding of the diverse determinants that influence health and specific healthy community elements relevant to the post-disaster period. These are described in the sections below.

As shown in Figure 2-1, population health outcomes (e.g., life expectancy, morbidity, quality of life) result from a number of different factors. Interventions to improve population health1 have historically placed significant emphasis on changing health-related behavioral choices of individuals and the quality of public health and health care delivery systems. Although these remain important determinants of health, there is growing awareness that the locally specific built, natural, and social environments—now understood to be social determinants of health (see Box 2-1)—also are prominent influences on health outcomes. As is increasingly understood, “place matters” to health. As expressed by one set of authors, “Your zip code is a powerful predictor of how healthy you are and how long you are likely to live” (Standish and Ross, 2014, p. 31). Such factors as the presence of safe places to be physically active, access to healthy and nutritious food, a clean environment, quality educational systems, accessible social services, and strong systems for community support can make a big difference in the health of an individual, as well as the health of a community. Yet a large number of communities in the United States lack even these basic features. According to the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Commission to Build a Healthier America, “nearly a fifth of all Americans live in unhealthy neighborhoods that are marked by limited job opportu-

________________

1 The term “population health” describes “the health outcomes of a group of individuals, including the distribution of such outcomes within the group” (Kindig and Stoddart, 2003, p. 380).

BOX 2-1

What Are the Social Determinants of Health?

“The social determinants of health are the circumstances in which people are born, grow up, live, work and age, and the systems put in place to deal with illness. These circumstances are in turn shaped by a wider set of forces: economics, social policies, and politics” (WHO, 2014b).

nities, low-quality housing, pollution, limited access to healthy food, and few opportunities for physical activity” (RWJF Commission to Build a Healthier America, 2014, p. 10).

Geographic variation in factors that influence health creates significant differences in health outcomes across segments of the population (i.e., health inequities). Within a single city, for example, life expectancy can vary by as much as 15 to 25 years depending on the neighborhood (Standish and Ross, 2014). Many of the factors that contribute to this observed effect of place are systemic, with roots in the nation’s historical social policies, such as segregation (e.g., racially restrictive zoning) and other policies related to civil rights that have created barriers to meaningful civic participation (IOM, 2014). Thus, the physical and social environments are inextricably linked, and targeted, place-based interventions aimed at changing those environments in ways that better promote health and address socioeconomic disparities could have a large impact on population health outcomes.

Elements of a Healthy Community

In Chapter 1, a healthy community is defined as

one in which a diverse group of stakeholders collaborate to use their expertise and local knowledge to create a community that is socially and physically conducive to health. Community members are empowered and civically engaged, assuring that all local policies consider health. The community has the capacity to identify, address, and evaluate their own health concerns on an ongoing basis, using data to guide and benchmark efforts. As a result, a healthy community is safe, economically secure, and environmentally sound, as all residents have equal access to high quality educational and employment opportunities, transportation and housing options, prevention and healthcare services, and healthy food and physical activity opportunities. (HRIA, 2013, p. 24)

Inherent in this definition is the premise that a healthy community is not a fixed entity but results from continual efforts to create and improve physical and social environments that allow community members to support each other in carrying out the day-to-day functions of living and achieving their full potential. To increase awareness among stakeholders regarding their role in shaping the conditions that affect health, a better understanding of what makes a healthy community is needed. The committee found a wealth of sources that describe elements of healthy communities, with significant overlap. One of the most comprehensive lists was developed by the California Health in All Policies2 Task Force as a healthy community framework (California Health in All Policies Task Force, 2010; Rudolph et al., 2013a). The committee adapted that framework to derive the list of healthy community elements in Box 2-2. Communities can use such resources to develop their own locally relevant healthy community vision and goals. More detailed discussion of the link between health and many of the elements listed in Box 2-2 is included in the sector-specific chapters of this report (Chapters 5-10).

________________

2 Health in All Policies is defined as “a collaborative approach to improving the health of all people by incorporating health considerations into decision-making across sectors and policy areas” (Rudolph et al., 2013a, p. 5).

BOX 2-2

Elements of a Healthy Community

A healthy community encompasses the following elements:

A safe, healthy, and aesthetically pleasing physical environment, including:

- All features of complete and livable communities (quality schools, recreational areas and facilities, child care, libraries, financial services, and other daily needs)

- Clean (i.e., free of toxins) indoor and outdoor environments, including air, soil, surfaces, and water

- Affordable and sustainable energy use

- Parks and green spaces, including a healthy tree canopy and agricultural lands

- A regional transportation grid featuring street connectivity and safe, sustainable, accessible, and affordable active and public transportation options

- Facilities and recreational areas for safe, affordable physical activity and policies that promote equitable access to those areas

- Accessible locations at which to obtain affordable and nutritious foods

- Affordable, high-quality, and location-efficient housing that meets national healthy housing criteria

- Building construction that incorporates universal design principles to support access for all community members

- Land use policies that help mitigate against known hazards

- Safe, functional, and resilient critical infrastructure

An inclusive, supportive social environment, including:

- A whole-community approach to strategic planning and problem solving, involving robust civic participation by empowered residents and leadership from community organizations and public officials

- An emphasis on data-driven decision making and ongoing quality improvement in all sectors

- Inclusive, supportive, respectful community social bonds, from the neighborhood to the regional level

- Resiliency to adapt to changing environments and emergencies

- Quality educational opportunities accessible to all residents

- Living-wage, safe, and healthy job opportunities for all residents and a thriving economy

- Safe communities, free of violence, crime, bullying, racism, and discrimination

- Integrated and accessible social and community services to address the spectrum of human needs efficiently and effectively

- Support for healthy development of children and adolescents

- Opportunities for engagement with arts, music, and culture

A high-quality, comprehensive health system, including:

- Affordable, accessible, high-quality, and patient-centered preventive health services and health care

- Emphasis on individual and family health literacy, capacity building, and empowerment

- A robust public health system that provides the essential public health services

SOURCE: Adapted from California Health in All Policies Task Force, 2010.

From the list in Box 2-2, several cross-cutting themes for healthy communities emerge:

- Equity—The World Health Organization defines equity as “the absence of avoidable or remediable differences among groups of people, whether those groups are defined socially, economically, demographically, or geographically” (WHO, 2014a). Health inequity denotes health disparities that

-

result from “systemic, avoidable and unjust social and economic policies and practices that create barriers to opportunity” (Rudolph et al., 2013a, p. 135).

- Resilience—Resilience is the ability to prepare and plan for, absorb, respond to, recover from, and adapt more successfully to adverse events. No person or place is immune from disasters or disaster-related losses. “Enhanced resilience allows better anticipation of disasters and better planning to reduce disaster losses” (NRC, 2012, p. 1). Although the term often is associated with disasters and climate change, the concept of resilience also applies to everyday challenges in communities, such as gradual economic decline.

- Sustainability—Building on the Brundtland Commission’s definition of sustainable development,3 sustainability can be described as “the ability of communities to consistently thrive over time as they make decisions to improve the community today without sacrificing the future” (McGalliard, 2012, p. 2).

Health, equity, resilience, and sustainability are interdependent and mutually reinforcing—part of the same virtuous cycle. As a result of this interdependence, initiatives that reduce inequities will yield benefits for population health, as will efforts to strengthen the sustainability or resilience of a community. Conversely, a healthy population is a critical component of sustainable and thriving economic and social systems (Rudolph et al., 2013b).

EQUITY, RESILIENCE, SUSTAINABILITY, AND HEALTH IN THE POST-DISASTER CONTEXT

Equity, resilience, and sustainability are all relevant to post-disaster efforts to build healthier communities. To better clarify these linkages, each is described below in the context of health and disaster recovery.

Equity is integral to a healthy, resilient, and sustainable community; conversely, policies and practices that are exclusionary and promote inequality undermine a community’s long-term viability. In an equitable society, differences in the conditions and successes of individuals are not strongly linked to categories such as ethnicity, race, gender, or disability status (ICMA, 2014). Unfortunately, too many communities are characterized by significant variability in access to essential goods, services (including health care), amenities, and opportunities (e.g., education, employment, and other social determinants of health) across subgroups (RWJF, 2008). This unequal distribution of resources often manifests as geographic clusters of poverty, crime, and poor health status. The World Health Organization has declared addressing the underlying inequities resulting from “poor social policies and programmes, unfair economic arrangements, and bad politics” an ethical imperative (CSDH, 2008, p. 1).

Disasters tend to expose and exacerbate preexisting inequities. Past experiences have shown that the impacts of disasters are not experienced equally across a community, and recovery proceeds at different rates for different groups. People with fewer resources (financial and social) struggle to recover more than their more affluent and connected peers do. Health disparities also can be exacerbated by disasters, resulting in poorer health outcomes for those already dealing with preexisting conditions such as chronic disease (Davis et al., 2010). In effect, the social determinants of health are also the determinants of social vulnerability (see Box 2-3). This is an important point not only at the individual level but also at the community level: a community with large concentrations of vulnerable populations will be less resilient in the face of social and economic disruption and slower to recover. Thus, addressing equity issues before a disaster is also a means of overcoming system weaknesses or vulnerabilities. Although the importance of addressing social vulnerability through comprehensive disaster risk reduction strategies (discussed in

________________

3 The Brundtland Commission defined sustainable development as “development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs” (World Commission on Environment and Development, 1987).

BOX 2-3

Social Vulnerability to Disasters

Disasters can be viewed as a result of the interaction between a hazardous event and a vulnerable community. “Vulnerability is place-based and context-specific” (NRC, 2012, p. 97), linked to both the physical environment (e.g., where communities are built, the strength of buildings) and social environments, inclusive of a variety of economic, political, and cultural conditions. The concept of social vulnerability refers to “the characteristics of a person or group and their situation that influence their capacity to anticipate, cope with, resist and recover from the impact of a natural hazard” (Wisner et al., 2003, p. 11), and stratification in this capacity is observed across groups of people as a result of inequalities. As a result, disaster impacts are experienced differently among and within communities. The inverse relationship between social vulnerability and resilience (discussed in the following section) is apparent from the congruence in their definitions, with resilience having been defined as the ability to prepare and plan for, absorb, respond to, recover from, and adapt more successfully to adverse events (NRC, 2012).

Chapter 1) is increasingly being acknowledged, the connection between efforts to address social vulnerability and activities aimed at reducing disparities in social determinants of health has not been widely recognized (Few, 2007; Lindsay, 2003), and this represents a missed opportunity to achieve synergy among different professional sectors with shared goals.

After a disaster, there may be new opportunities to address inequities and related social vulnerability issues through recovery efforts. However, leveraging these opportunities requires careful planning in which equity is intentionally included as an objective, and special attention is given to accessibility, affordability, and inclusiveness as the community rebuilds. Recovery practices that intentionally or unintentionally exclude marginalized groups can instead deepen inequities. The committee heard in testimony that “not in my backyard” attitudes can arise during recovery and create significant tension within communities, potentially driving displacement of low-income and other underserved groups (disaster-related gentrification). For example, rebuilding of public housing became a hotly debated and highly politicized topic in Galveston, Texas, after Hurricane Ike (Nolen, 2014). However, discussions on health and creating healthy communities provided a pathway for overcoming these “not in my backyard” concerns and polarizing issues such as public housing. When these concerns and issues are presented in the context of the health and well-being of the whole community, common ground can be found (Nolen, 2014). Indeed, health and wellbeing have previously been described as foundations for expanding social equity initiatives (ICMA, 2014).

Examples of efforts that promote both social equity and health that may be relevant to post-disaster recovery include but are not limited to

- supporting development of affordable housing,

- providing housing options well suited to the elderly and disabled,

- developing transportation programs specifically for low-income residents and expanding bus routes,

- building community centers that offer educational and recreational programs designed to bring all members of a community together,

- ensuring access to information technology/the Internet for all residents (which helps ensure inclusiveness since digital forms of communication are increasingly being used),

- developing energy reduction programs to assist low-income residents,

- creating workforce development programs for underserved groups to increase economic stability among vulnerable populations, and

- developing initiatives to address food deserts (ICMA, 2014).

To be optimally effective, however, communities require complementary investments targeted to areas of greatest need (data-driven), leveraging cross-sector collaborations and aligned funding streams.

Resilience is multifaceted, and it can refer to infrastructure, individuals, environmental or economic systems, and organizations. Growing concerns regarding climate change and experiences from recent disasters such as Hurricanes Katrina and Sandy and the Deepwater Horizon oil spill have prompted greater attention to resilience among the emergency management, health, environmental, and public policy sectors. Such initiatives as 100 Resilient Cities—pioneered by the Rockefeller Foundation—are enabling cities around the world to learn from each other and develop a road map for becoming more resilient to the physical, social, and economic challenges resulting from sudden events (e.g., disasters such as hurricanes and earthquakes), as well as chronic stresses that weaken the fabric of a community (e.g., unemployment, an overtaxed or inefficient public transportation system, community violence, food and water shortages) (100 Resilient Cities, 2014).

Health status and resilience (or inversely, vulnerability) are intimately linked at both the individual and community levels. As stated by LTG Russell Honoré, Commander, Joint Task Force, Katrina, “The health of a community before any crisis has a direct correlation to the magnitude of the health crisis after the event” (Honoré, 2008, p. S6). Unhealthy individuals suffer more severe consequences when routine health system functions and social networks are disrupted and may require more time and resources to recover. For example, chronic diseases are exacerbated as routine disease management services are interrupted and access to nutritious food and medications is impeded (Davis et al., 2010).

Resilience-building efforts generally are aimed at reducing the impacts of future disasters,4 including impacts on health and the length of the recovery period. At the same time, however, actions that can be taken to make communities less vulnerable, and thus more resilient, also benefit the community in the everyday context through improvements in community health and well-being—for example, by addressing social determinants of health that create social vulnerability. This point is of paramount importance because in a fiscally constrained environment, investment in resilience (i.e., the future) is easier to justify when there are co-benefits to the community and its well-being beyond the disaster context (i.e., today). Community health resilience then emerges within this dual opportunity space that represents the intersection of community health promotion and emergency preparedness and provides a mechanism for alignment (Chandra, 2014). The process of building community health resilience has been described as a “reframing of long-standing approaches to improve community well-being” (Plough et al., 2013, p. 1190). Under this aligned framework, coalitions and partnerships developed for purposes of emergency preparedness and resilience can be leveraged for health promotion and disease prevention initiatives and vice versa (Plough et al., 2013). The resulting efficiency should have broad appeal as funding for both public health emergency preparedness and community health promotion continues to decline.

Like health status, social connectedness is a human characteristic that affects resilience at both the individual and the population level. Social networks are formed from the connections among community residents, as well as residents’ connections with individuals and organizations outside of their community (Bourdieu, 1986; Coleman, 1988; Granovetter, 1973). Previous experience has shown that communities with high levels of social connectedness (often referred to as social capital) display resilience that serves them well during post-disaster recovery (Aida et al., 2013; Aldrich and Sawada, 2014; Cutter et al., 2003; Nakagawa and Shaw, 2004). Individuals and communities with shared norms and strong ties can better connect to critical resources and mobilize to overcome problems that arise during a crisis through collective action (Adeola and Picou, 2012; Aldrich and Crook, 2008; Hurlbert et al., 2000; Kawachi et al., 2008). Following a disaster, many of the standard providers of resources and services—such as medical,

________________

4 It should be noted that resilience-strengthening activities undertaken during the disaster response/early recovery stages can improve the efficiency of recovery (shorten recovery time) in addition to providing protection against future disasters (Chandra, 2014).

retail, and child care—are shut down for days, if not weeks. These resources and services may be available only through friends, family, and neighbors, and they can be better accessed by individuals with stronger connections following a catastrophe (Hurlbert et al., 2000).

A number of the challenges faced by communities following a disaster occur at the neighborhood or block level, not the individual level. When a disaster strikes, and many times beforehand, social networks help organize evacuations. After a disaster, social capital continues to help communities mobilize as a collective. If only a single homeowner decides to clean up disaster debris, for example, the property values of that and the neighbors’ homes will not stabilize, but when all members of a neighborhood work together, they can improve the appearance of the whole area. Social ties to an area are important to its recovery because for many without such ties, the high costs of returning, including financial, opportunity, and psychological burdens, may overwhelm the benefits, and they may choose to start life anew elsewhere.

Like other forms of capital, social capital can be deliberately created. Double-blind field experiments have demonstrated that deliberate interventions can deepen existing bonds in a community regardless of its socioeconomic status or level of homogeneity (Brune and Bossert, 2009; Pronyk et al., 2008). Ideally, such efforts should be undertaken before a disaster as a component of resilience-building initiatives and may entail either top-down or bottom-up approaches (see the examples in Box 2-4).

Disaster recovery can be viewed as a special case of the ongoing sustainable community development process, with the benefit of linking recovery to existing sustainability planning activities in many communities5 (Natural Hazards Center, 2005). In sustainable development, values related to physical, economic, and social environments are balanced so that contemporary communities can thrive without compromising future generations (ICMA, 2014). The achievement of that balance results in communities that are livable (built in a way that allows residents to live the lives they want to live), equitable (such that the burdens and benefits of policy decisions are distributed evenly across a community), and viable (with policies and practices being flexible enough to adapt to changing needs and not compromising future generations).6 Needs related to these same three environments (physical, social, and economic) must be addressed holistically during recovery.

Although health and well-being are implicit in these concepts, there has been increased attention recently to addressing health issues strategically in the context of sustainability (Mishkovsky, 2010). When health is integrated into ongoing sustainability planning efforts, accountability extends beyond the public health agency to the broader local government. Because development decisions made by local government policy makers shape so many aspects of the physical, social, and economic environments that impact health, there is growing consensus that these leaders should work more consciously and deliberately to achieve public health goals (Mishkovsky, 2010).

U.S. sustainability policy leapt forward in 2009 with the development of the Partnership for Sustainable Communities—a joint initiative of the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), the U.S. Department of Transportation (DOT), and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)—and its six principles for livability (see Box 2-5). Over the past 5 years, HUD, DOT, and EPA have improved coordination and collaboration to better align federal policies and investments, reducing duplication and facilitating comprehensive and integrated solutions to the complex and interrelated economic, environmental, and social challenges that impede the realization of healthy communities (Partnership for Sustainable Communities, 2014). With increasing support from federal leadership, communities nationwide

________________

5 Although the term “sustainability” may for some denote only efforts to address long-term environmental problems (e.g., climate change) or issues of financial affordability, the committee uses it in its broadest sense to include dimensions of environmental integrity, economic viability, and social equity (ICMA, 2014).

6 In some communities, strategic planning focuses on these three core values rather than an explicit commitment to sustainability, which is a more politically charged term (ICMA, 2014).

Top-Down Approaches to Building Social Capital

Following the 2011 New Zealand earthquakes, the central government set up the Canterbury Earthquake Recovery Authority (CERA) to coordinate recovery efforts; among its core interests was strengthening social capital in the area by building efficacy and community connectedness. CERA has worked to use funds collected from the lottery to support the Community Organisation Grants Scheme by streamlined application processes. Through this program, volunteers can receive funds to support the development of local community and nongovernmental organizations. Further, CERA tracks various indicators of social capital in the area, including volunteering rates and sense of belonging, to track how its programs are impacting local community members. Through these top-down programs, the central government has strengthened the resilience of the community (CERA, 2013a,b).

Bottom-Up Approaches to Building Social Capital

San Francisco, California

In recognition of the value of strong community bonds and social networks to a region, a collaborative was formed in 2007 in San Francisco, California. This initiative brought together city agencies, business associations, corporations, community organizations, nonprofit and faith-based institutions, foundations, and academic centers around the mission of empowering their neighborhoods with the capacity to build resiliency. This collaborative, known formally as the Neighborhood Empowerment Network (NEN), has focused on using a grassroots approach to design tools and resources for use in all stages of community organization (NEN, 2014a).

NEN has established programs in several areas—including public safety, education, infrastructure, and emergency management—focused on building social capital in San Francisco neighborhoods. One such program, Resilientville, is a role-playing exercise aimed at developing awareness of the benefits of problem solving at the neighborhood level and strengthening the ability of residents to respond collectively to a wide variety of unforeseen challenges and opportunities by encouraging community members to focus first on daily issues

are integrating smart growth, environmental justice,7 and equitable development approaches to create the healthy, equitable, and sustainable communities that Americans have shown they want (Partnership for Sustainable Communities, 2014). In the post-disaster environment, sustainable redevelopment efforts often focus on hazard mitigation, but this focus reflects a narrow view of sustainability. As discussed in Chapter 1, increasing involvement of federal agencies, including HUD and EPA, with broader sustainability agendas is focusing more attention on interrelated economic, environmental, and public health outcomes.

The Need for an Explicit Focus on Health

The concept of capitalizing on the unique opportunities to reshape a community after a disaster is not a novel one, and sustainability and (more recently) resilience are common goals in recovery efforts focused

________________

7 EPA defines environmental justice as “the fair treatment and meaningful involvement of all people regardless of race, color, national origin, or income with respect to the development, implementation and enforcement of environmental laws, regulations and policies” (EPA, 2014). Environmental justice concerns have arisen primarily in response to empirical data showing that minority, tribal, and low-income groups are disproportionately exposed to environmental health hazards.

(SFDEM et al., 2015). Other events include parties, door-knocking events, and festivals, along with community planning meetings and block captain nominations.

In the low-income neighborhood of Bayview, for example, residents from a variety of age and demographic groups now meet regularly to implement a Resilience Action Plan (NEN, 2014c). Many of the participants had little connection to each other or city decision makers before these meetings began, but the increased communication, participation, and trust among residents enable them to participate collectively in problem solving and in planning for future disasters (NRC, 2012).

NEN also has launched a pilot initiative, the Empowered Communities Program, which is focused solely on building the neighborhood engagement that could make the difference for communities following a disaster or emergency. Modeled after the core tenets of the Federal Emergency Management Agency’s (FEMA’s) Whole Community Approach, this program “supports communities as they work to achieve a pre-event condition that will allow them to perform at the highest level in times of stress” (NEN, 2014b). The program includes forming partnerships with organizations that are not traditionally identified as disaster preparedness institutions (i.e., schools, civic groups), as well as focusing on building the social capital characteristics of trust, ownership, and cooperation within a community.

Lyttelton, New Zealand

Well before major earthquakes struck New Zealand in 2010 and 2011, the community of Lyttelton had established a time-banking program to develop local cohesion and build trust among residents. In 2005, the community of some 3,000 people set up a time bank whereby residents exchanged skills and earned credits for doing work for others that were traded for services. In exchange for transporting a neighbor to the doctor, for example, one could earn on hour of gardening on one’s property. Community currencies and other time-banking programs have been shown to increase levels of social capital and trust (Richey, 2007). Having this program in place well before the earthquakes struck allowed local residents in Lyttelton’s various organizations to work together in a nonemergency situation and build trust and experience. When the disaster struck, emergency providers worked seamlessly following the event and had various focal points, including local cafés and recreation centers, that served as hubs for recovery programs (Jefferies, 2012). The community’s cohesion allowed it to develop its own vision for development and to move more effectively toward recovery (Ozanne, 2010). For more information, see Lyttelton Harbour Timebank, available at http://www.lyttelton.net.nz/timebank (accessed April 4, 2015).

on “building back better.” It is clear from the above descriptions that equity, resilience, and sustainability are inextricably linked and that, ultimately, the community’s health and welfare are drivers of each. Nonetheless, the committee strongly believes there is still a critical need for both health and non-health sectors to include an explicit focus on health in recovery planning to ensure that recovery activities do not have unintended negative impacts on health, that opportunities to create healthier communities are not lost, and that health outcomes are tracked and used as measures of program success. At the same time, however, it is also critical that a healthy community approach to recovery not be presented as an alternative to post-disaster resilience and sustainability initiatives. Separate efforts that fail to recognize the links among these concepts dilute resources, cause confusion, and perpetuate silos.

The measurement and evaluation of recovery strategies focused on health improvement has been a sorely neglected area of research. Evaluation of programs or projects during recovery is conducted primarily in terms of process measures (e.g., numbers of individuals served) rather than outcome measures (e.g., changes in health status indicators). Consequently, the committee found a paucity of data on the return on investment from post-disaster investments in health improvement strategies. However, experience from healthy community initiatives outside the disaster context suggests that investing in health-promoting

BOX 2-5

Six Livability Principles of the Partnership for Sustainable Communities

The Partnership for Sustainable Communities is an interagency partnership among the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, the U.S. Department of Transportation, and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s Office of Sustainable Communities. Its six livability principles are as follows:

- Provide more transportation choices. Develop safe, reliable, and economical transportation choices to decrease household transportation costs, reduce our nation’s dependence on foreign oil, improve air quality, reduce greenhouse gas emissions, and promote public health.

- Promote equitable, affordable housing. Expand location- and energy-efficient housing choices for people of all ages, incomes, races, and ethnicities to increase mobility and lower the combined cost of housing and transportation.

- Enhance economic competitiveness. Improve economic competitiveness through reliable and timely access to employment centers, educational opportunities, services, and other basic needs by workers, as well as expanded business access to markets.

- Support existing communities. Target federal funding toward existing communities—through strategies like transit-oriented, mixed-use development and land recycling—to increase community revitalization and the efficiency of public works investments and safeguard rural landscapes.

- Coordinate and leverage federal policies and investment. Align federal policies and funding to remove barriers to collaboration, leverage funding, and increase the accountability and effectiveness of all levels of government to plan for future growth, including making smart energy choices such as locally generated renewable energy.

- Value communities and neighborhoods. Enhance the unique characteristics of all communities by investing in healthy, safe, and walkable neighborhoods—rural, urban, or suburban.

SOURCE: Excerpted from Partnership for Sustainable Communities, 2013.

measures during recovery will yield benefits at the individual and community levels and may also result in significant downstream savings in health-related and other societal costs (see Box 2-6).

THE NEED FOR AN INTEGRATED APPROACH

The concept of vulnerability, discussed above, creates an interface for two fields that both are developing more proactive approaches to ameliorating the elements that contribute to vulnerability but have been “doing so along parallel paths” (Lindsay, 2003, p. 292). Disaster management professionals from a variety of sectors (e.g., emergency management, urban planning) have shifted their focus away from the hazardous event itself to minimizing the event’s negative impact on the community. Accordingly, greater emphasis has been placed on understanding the factors that make communities vulnerable. The health

BOX 2-6

Why Invest in Healthy, Resilient, and Sustainable Communities?

- Improve quality of life—Health has a significant impact on quality of life. Many steps that improve the physical and social environments of a community also improve quality of life by making communities more livable and reducing the chronic stresses associated with inadequate access to basic needs.

- Reduce health-related costs—Poor health comes at a significant cost for individuals, communities, and the nation. Annual health care spending in the United States has grown to approximately $2.7 trillion, more than 75 percent of which goes to the management of preventable, chronic diseases (IOM, 2012; KFF, 2012; RWJF Commission to Build a Healthier America, 2014). Changes to the physical and social environments that promote health and prevent disease will reduce the unsustainable costs associated with the treatment of disease.

- Stimulate economic vitality—Beyond health care–related costs, unhealthy communities are bad business more generally. Failure to attend to the social determinants of health (employment, education, food access) can lead to high human service costs and a vicious cycle of disinvestment and depopulation. Healthy, livable communities attract residents and businesses, spurring improvement in economic vitality (Cornett, 2014).

- Reduce vulnerability to hazardous events—As discussed earlier in this chapter, social vulnerability and deficiencies in physical health increase the susceptibility of individuals and communities to the negative effects of a hazardous event. Disasters are associated with a variety of significant societal and financial costs that can be reduced through health improvement and resilience initiatives that bolster the ability of individuals and communities to cope with adversity.

sector simultaneously has been moving away from a reactive, treatment-focused approach to a population health model. As a result, it has been working to understand and address the upstream causes of the suboptimal health status observed within and across the nation’s communities. However, a health-focused approach to pre- and post-event (i.e., recovery-related) mitigation that addresses social vulnerabilities has been largely neglected; great benefit can potentially be achieved by bringing these paths together (Lindsay, 2003).

The committee notes with optimism a national policy context for achieving this goal. As noted in Chapter 1, the National Health Security Strategy places unprecedented emphasis on community health resilience—“the ability of a community to use its assets to strengthen public health and healthcare systems and to improve the community’s physical, behavioral, and social health to withstand, adapt to, and recover from adversity” (HHS, 2015, p. 10). It proposes the following vision for building and sustaining healthy, resilient communities:

The nation will create a robust culture of health resilience, promoting physical and behavioral health and well-being, connecting communities, and championing volunteers. Across the nation, communities, organizations, and individuals will all contribute through their unique resources and capabilities. A culture of resilience will equip them not only to address daily challenges, but also to prevent, prepare for, mitigate, respond to, and recover from large-scale emergencies. Individuals and households will know how to improve health and will act on that knowledge. They will be engaged with the healthcare system and understand how to support their neighbors and community. Households and communities will work together, with the support of local organizations, and will engage in training and planning that prepare them to fulfill their roles in health security. Communities will promote health in part by supporting community infrastructure, including secure housing, economically viable neighborhoods, quality healthcare facilities, and spaces for

gathering and exercise. Public health, healthcare, behavioral health, and social service organizations will understand the needs of the people they serve and be ready to meet those needs before, during, and after an incident. As individuals and organizations become more health-resilient and build robust social networks, whole-community resilience will thrive. (HHS, 2015, p. 10)

Of critical importance is the acknowledgment in this national policy document that this vision cannot be achieved by the actions of any one sector; a wide variety of capabilities and partners must be brought together (HHS, 2015). The health sector can work to reduce the vulnerability of its own facilities and programs, and it can advocate for measures that reduce the vulnerability of communities and their residents by strengthening community systems and addressing social determinants of health. However, every resident and organization within the community has a role to play and a responsibility to help break the negative cycle by which disasters exacerbate preexisting vulnerabilities. Leveraging the opportunities afforded by recovery to advance this health-focused approach to community resilience and ultimately the creation of healthier communities will require an understanding of the nature of a community as a complex system and a mechanism for incorporating health considerations across all elements of that system.

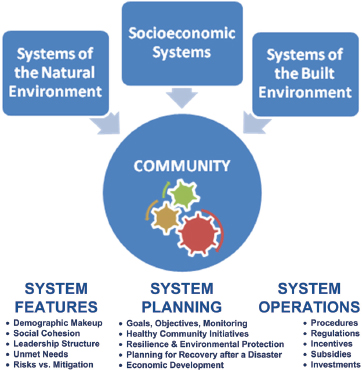

To contemplate options for building healthier and more resilient and sustainable communities after disasters, the community is best viewed from a systems perspective (see Box 2-7 and Figure 2-2). According to Duhl (2000, p. 116), “cities must be looked at as interrelated complex ecological organisms in which

BOX 2-7

The Community as a System:

Interdependence Among Sectors Influences Recovery

A community is not simply a collection of buildings and inhabitants; it represents a complex “system of systems.” A sharp distinction often is made between infrastructure and systems, with systems viewed as encompassing the combination of human needs and human services, but such a distinction fails to capture the critical interdependencies among sectors.

This point is illustrated by the example of Greensburg, Kansas, which received global attention for its investment in sustainability after a tornado in 2007 demolished 90 percent of the small rural town. The town made the choice to rebuild and to rebuild greener. Greensburg now has wind turbines providing power to the town and a plethora of energy-saving Leadership in Energy & Environmental Design (LEED) Platinum buildings (ULI, 2014). What it does not have (in adequate supply), however, is affordable housing stock. A three-bedroom home that would have cost $50,000 or $60,000 before the tornado is now priced at upwards of $160,000. The town lost about 50 percent of its population after the storm (Montgomery, 2014). Although population loss is common after a major disaster when displaced residents decide not to return, the lack of affordable housing serves as a barrier to drawing in new residents. Decisions regarding the recovery of the housing sector affect not only the overall economic recovery of the town but also other sectors in less expected ways. For example, Greensburg now has the first critical access hospital to reach LEED Platinum status. However, according to Mary Sweet, hospital administrator for Kiowa County Memorial Hospital, a number of the current staff live outside the town, and recruiting new staff has been a challenge because of the now relatively high cost of living in this small rural town (personal communication, Mary Sweet, Kiowa County Memorial Hospital, September 10, 2014). In the event of an emergency, this means that few of the local medical personnel will be nearby during off-duty hours to provide assistance, impeding the capacity of the medical system.

SOURCE: B. Hokanson/PLN Associates.

housing, transport, city planning, economic development, and many other facets interact with health and medical issues.” During recovery planning, interdependencies among components of the system need to be understood so that opportunities for synergy can be identified and unintended consequences can be avoided (see Box 2-7).

Community systems operate through a range of public and private initiatives. Some components of the overall community system are extensively planned and programmed, with established protocols, methodologies, budgeting, and subsidies. Transportation and land use planning, for example, are routine functions of communities and metropolitan areas, representing among the most highly organized influences on the configuration of community systems. Personal investments in housing and transportation are heavily influenced by public systems such as roads, development controls, utility lines, and public services. Commerce and government serve the population with education, employment, and the distribution of goods and services. There are gaps in these systems, however, causing unemployment, poverty, and hardship, with additional consequences affecting the health and well-being of families and individuals. In many cases, these social dysfunctions are concentrated in areas of blight and deterioration with high crime, low educational attainment, and unhealthy living environments.

All communities have processes in place to try to remediate these gaps through both place- and people-focused interventions. For example, community development programs attempt to address social dysfunction in communities through job training and a combination of public and private investment in neighborhood revitalization. The social services sector offers early childhood interventions and food access programs. Public health agencies may offer health services to the most vulnerable members of communities through a safety net system. In many cases, these programs and activities will target the same geographic regions and populations within a community, utilizing a systems approach to achieve synergies through

coordinated investments. Because disasters create dysfunction similar in nature to that which already exists in communities (although a disaster will increase the magnitude of the problem), these ongoing community remediation processes are important assets that can and should be augmented and leveraged to address post-disaster community needs and improve health outcomes.

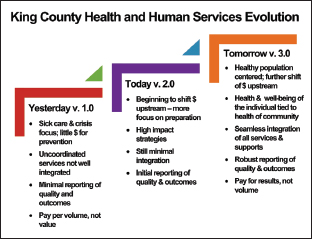

In the course of its research, the committee found examples of forward-looking communities that, recognizing the connections among system components (economic opportunity, social cohesion and stability, the conditions of the built and natural environments, and health), are developing strategic approaches that employ an array of diverse but coordinated place-based initiatives to address the complex and interrelated challenges posed by concentrated poverty, crime, blight, and economic decline. In Washtenaw County, Michigan, for example, cooperative agreements were used to create a collaborative organizational structure and a single, coordinated funding process to facilitate investment by county and municipal governments, local nonprofits, and foundations in human services initiatives related to safety net health services, hunger relief, homelessness, the elderly, children and youth, affordable housing, parks and recreation amenities, and workforce development (ICMA, 2014). In King County, Washington, persistent health disparities and unsustainable health care costs are spurring the implementation of a transformation plan that will facilitate the integration of health, human services, and community-based prevention (see Box 2-8) (King County, 2013). Similar efforts are under way in nearby Thurston County, Washington (see Box 2-9).

These initiatives are in many cases being driven by health sector stakeholders with the support of public and elected community leaders (with federal and state incentives) who are sensitized to the substantial social and economic costs associated with these chronic challenges, including significant health care–related costs arising from the association between poverty and poor health. Such initiatives, which are designed to yield improved health and social outcomes, as well as cost containment and economic vibrancy, require alignment of funding and collaborative efforts across a number of departments and nongovernmental entities, including health and human services, community development, education, law enforcement, economic development, housing, and urban planning. The process of developing and implementing these kinds of initiatives is a valuable asset that can be leveraged during disaster recovery since disaster-related deterioration of social, economic, and physical environments creates an end result similar to that of declines that take place over a much longer period of time. Moreover, as discussed further in Chapter 3, the same stakeholder groups that are involved in these initiatives should be engaged in the disaster recovery process.

A Health in All Policies Approach to Disaster Recovery

As discussed earlier in this chapter, intentional consideration of health, including health equity, is necessary during recovery to mitigate the negative effects of a disaster and seize opportunities to advance population health and well-being. Although disasters have direct impacts on health in the short term, negative effects on health also arise in the long term through the impacts of the disaster on social determinants of health, often exacerbating preexisting health inequities. Optimizing post-disaster health outcomes involves addressing acute conditions but also finding synergies to help overcome chronic health problems, thus advancing the achievement of a healthy, resilient, and sustainable community.

Since a community’s social and physical environments are shaped largely by the decisions and actions of nonhealth sectors, those sectors must be sensitized to the potential impacts of their activities on health outcomes and should be actively engaged in efforts to protect and promote health throughout the recovery period. The integration of health considerations into decision making across all sectors has been termed Health in All Policies (HiAP). The World Health Organization has put forth the following definition of HiAP:

Health in All Policies is an approach to public policies across sectors that systematically takes into account the health implications of decisions, seeks synergies, and avoids harmful health impacts, in order to improve population health and health equity. (WHO, 2013)

BOX 2-8

Health and Human Services Transformation in King County, Washington

“Our region’s health and human services delivery system is fragmented, focused more on providing costly late-stage care than on preventing crises from happening in the first place, and has not adapted to demographic trends that call for a shift in how and where services are delivered. With our partners, King County is working to create a system that is responsive, customer friendly, and focused on prevention and the social and health outcomes that support healthy and vibrant people and communities.”

—King County Executive

Dow Constantine (King County, 2014)

While King County is on average one of the healthier counties in the nation, behind the averages lie large disparities in health and unequal access to opportunities and choices. Among different zip codes in the county, for example, life expectancy varies by almost 10 years, obesity rates range from 8 percent to 35 percent, and the rate of uninsured residents ranges from 3 percent to 30 percent. To address these disparities, as well as the high costs of health care, the Metropolitan King County Council passed Motion 13768 in 2012, requesting that the county executive create a plan for integrating the systems of health, human services, and community-based prevention (King County, 2013).

The Health and Human Services Transformation Plan, accepted by the Council in 2013, charts a course for improving health and well-being by shifting “from a costly, crisis-oriented response to health and social problems, to one that focuses on prevention, embraces recovery, and eliminates disparities by providing access to services that people need to realize their full potential” (King County, 2013, p. 6). The plan, fueled by a vision that all people in the county should have “the opportunity to thrive and reach their full potential,” is focused on improving and integrating systems at two levels—individual/ family and community (King County, 2013, p. 20). The plan lays out a whole-person approach that acknowledges that social and health conditions are intertwined, and that a person’s care must be holistic, seamless, and extend across multiple domains (e.g., housing, health promotion, clinical services, employment). At the community level, the plan focuses on improving the conditions in the community (e.g., education, food security, access to parks), recognizing that a person’s health is determined in large part by the community in which he or she lives (King County, 2013). Thus King County is applying both people- and place-based strategies for improving the lives of its community members.

The planning and implementation of this initiative have brought together stakeholders from social services, health care, government, and nonprofits whose focus ranges from housing to developmental disabilities. The initiative has broken down silos by integrating social services, community development, health prevention, and health care, allowing for more holistic, efficient, and effective care for individuals and communities. After any disaster, sectors are forced to work together to respond to the myriad needs of affected individuals and communities. Thus by establishing this integrated system with input from multiple stakeholders before a disaster strikes, King County may be better prepared in the event of a disaster. The communication, collaboration, and integration that are the backbone of the Transformation Plan have the potential to result in more organized and successful disaster response and recovery.

SOURCE FOR FIGURE: King County, 2013. Health and Human Services Transformation Plan. King County, Washington. p. 19. Available at http://www.kingcounty.gov/elected/executive/health-human-services-transformation/background.aspx.

Thurston Thrives is an initiative developed to unite a wide range of community partners from within Thurston County, Washington, around the shared goal of making Thurston a healthy and safe place to live. One of the main focuses of the project is on aligning public health and social services efforts to promote health and social well-being in the community more effectively by addressing many of the social determinants of health through policy decisions. The program was initiated by the Thurston Board of Health but aimed to engage leaders from across numerous stakeholder groups. Thus, the 13-member Advisory Council for Thurston Thrives comprises representatives from the governmental, nonprofit (e.g., United Way and Habitat for Humanity), and private sectors and includes professionals from the fields of health, housing, economic development, education, planning, and social services. Thurston Thrives is using action teams to develop targets and strategies for achieving those targets for the following nine major areas that affect the health of the community:

- Child/youth resilience

- Clinical care and emergency care

- Community design

- Community resilience

- Economy

- Education

- Environment

- Food

- Housing

Each of these action areas would be relevant to the post-disaster environment. Thus, great efficiencies could be achieved by leveraging these preestablished transdisciplinary teams in disaster recovery planning.

SOURCE: Thurston County Board of Health, 2015.

A HiAP approach is founded on health-related rights and obligations. It emphasizes the consequences of public policies on health determinants and aims to improve the accountability of policy makers for health impacts at all levels (WHO, 2013). Motivation for a HiAP approach comes from understanding that “good health is fundamental for a strong economy and vibrant society, and that health outcomes are largely dependent on the social determinants of health, which in turn are shaped primarily by decisions outside the health sector” (Rudolph et al., 2013b, p. 1). Adoption of HiAP by all levels of government has been recommended by several organizations, including the Institute of Medicine (IOM, 2011), the National Association of County and City Health Officials (NACCHO, 2012), and the Association of State and Territorial Health Officials (ASTHO, 2013).

The committee asserts that not only is the aftermath of a disaster a prime opportunity to apply a HiAP approach; it in fact poses an acute need for this approach. Governmental public health agencies are an essential component of the diverse web of entities that make up the health system responsible for providing the health-related, population-based services required to create conditions in which people can be healthy. However, governmental public health acting alone cannot be successful in addressing the complex population health challenges faced by communities, particularly after a disaster. Partnering with other governmental and nongovernmental organizations brings

- new opportunities to influence policy (outside of the health sector) and spur system-level changes, and

- a means of yielding improved health outcomes from funds being spent in other sectors.

However, as indicated to the committee by James Blumenstock, chief program officer of ASTHO’s public health practice division, the connection between disaster recovery and HiAP has not been adequately made. Referring to ASTHO materials on HiAP, Blumenstock said that “while everything in writing is relevant to post-disaster recovery, there is absolutely no reference to post-disaster recovery as an opportunity or an issue or a circumstance where health in all policies needs to apply. No examples, no case studies, no verbiage basically linking the two” (Blumenstock, 2014). In point of fact, the committee found only two examples of the application of HiAP to disaster recovery operations. In New Zealand, the HiAP approach to recovery was government led, and the recovery process was recognized as an opportunity to advance HiAP efforts already under way by local health agencies (Stevenson et al., 2014). As a result of early successes, HiAP has become more institutionalized, with regular public health input into major policies (see Box 2-10). In the second case, an academic organization, the Center to Eliminate Health Disparities at University of Texas Medical Branch, championed a HiAP approach to recovery in Galveston after the devastating effects of Hurricane Ike (see Box 2-11). The Galveston case study demonstrates the challenges of applying a HiAP approach to disaster recovery without adequate pre-disaster investment in building cross-sector relationships (such as that illustrated by the King County and Thurston County examples described in Boxes 2-8 and 2-9, respectively) and support for creating healthier communities.

The HiAP concept is compatible with the “whole-community” approach to integrated disaster recovery now being promoted by the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) and others (described in Chapter 3). As a result of the failure to apply a HiAP approach more broadly, the health sector, like many

BOX 2-10

Advancing Health in All Policies After Disasters: A Case Study from New Zealand

In 2010 and 2011, a series of earthquakes struck Canterbury, New Zealand (see also Box 2-4); the most severe aftershock occurred on February 22, 2011, in the city of Christchurch. It caused mass destruction in the central city, leading to 185 deaths and more than 65,000 injuries and destroying more than 6,000 residential properties (Stevenson et al., 2014). Prior to the earthquake, the Canterbury District Health Board had been working on a health impact assessment on urban development programs as part of a broader Health in All Policies (HiAP) initiative, under which the multi-agency Canterbury Health in All Policies Partnership was formed. The local Public Health Unit leadership team, involved in these prior efforts, “recognised that this was an opportunity to ‘leapfrog’ to the HiAP approach and consequently, immediately after the February earthquake, the unit was reconstructed in order to prioritize HiAP and support staff to utilise a determinants framework in all areas of their work” (Stevenson et al., 2014, p. 125). Federal grants were allocated from the Ministry of Health to mobilize a HiAP team within the Public Health Unit, focused on post-disaster recovery issues. One particular area of focus was the promotion of health-centered urban designs in the Canterbury communities. The HiAP team also has provided input to local and regional policy makers on such issues as air quality, water quality, and building standards and ensured that local public health officials and community members are included in the recovery planning cycle. According to Stevenson and colleagues (2014, p. 126), “The HiAP team continues to lead major interagency collaborative projects with the result that public health input into major policy is now routinely sought at an early stage by our local and regional government partners.”

Hurricane Ike struck the island of Galveston, Texas, in September 2008. The city’s population of 50,000 faced pervasive devastation, largely from flooding, with 70 percent of city buildings being destroyed or badly damaged. According to Dr. Alexandra Nolen, director of the University of Texas Medical Branch Center to Eliminate Health Disparities (CEHD), the city’s health and safety network was essentially wiped out, as was its communication and social infrastructure. While Hurricane Ike brought significant challenges for all residents of the ravaged island, the city’s disproportionately high number of low-income residents, with their poor health and social indicators, faced an even more uncertain recovery. But amidst the chaos, Dr. Nolen and her center envisioned an opportunity to tap into the investment dollars flowing in for Galveston’s recovery to rectify health disparities and create a model healthy community.

Funded by two grants beginning in October 2009, Dr. Nolen and her center sought to increase the evidence base for post-disaster recovery planning through informed policy making related to the social determinants of health. She was driven by the hypothesis that post-disaster environments afford opportunities for local planners to address health disparities through the lens of Health in All Policies (HiAP).

The strategy behind CEHD’s efforts centered on three pillars of action: (1) assembling an evidence base on local challenges related to social determinants of health, (2) raising community awareness and knowledge of social determinants of health through education and engagement, and (3) partnering with decision makers and planners to incorporate evidence-based recommendations into the planning process.

To assemble evidence on local health challenges, CEHD adapted the Sustainable Communities Index (also known as the Healthy Development Measurement Tool, or HDMT) to a post-disaster context, tested its applicability, and drew lessons more generally on using this tool to improve health in a post-disaster planning environment. The HDMT was originally developed by the San Francisco Department of Public Health for the purpose of improving community health through urban development projects. The National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant to CEHD also funded geographic information systems (GIS) mapping of 125 health-related indicators from the HDMT, including indicators of environmental stewardship, sustainable and safe transportation,

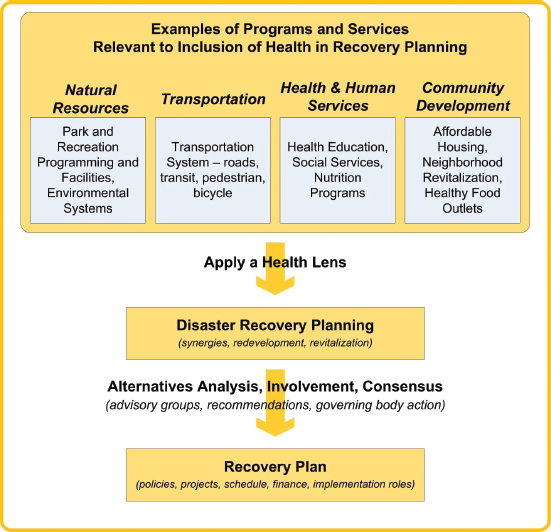

others involved in disaster recovery, has tended to act in isolation rather than as part of a coordinated, multidisciplinary group. HiAP in the recovery context is about (1) creating organizational structures that optimally enable the coordination of efforts and the creation of synergies whereby core missions of other sectors align with healthy community objectives, and (2) ensuring that information on potential health impacts of recovery decisions is available to the decision makers within those structures. These processes are discussed further in Chapter 3, but roles for health professionals in facilitating a HiAP approach to disaster recovery can include

- assembling the evidence base (data) on local challenges,

- raising community awareness (in the public but also among other sectors) regarding the myriad factors that affect health, and

social cohesion, public infrastructure/access to goods and services, adequate and healthy housing, and healthy economy. The GIS mapping showed that the hurricane adversely affected the social determinants of health: it left more concentrated poverty and segregation, fewer grocery stores, quick recovery of low-nutrition fast-food restaurants, greater environmental hazards from toxins in the sediment, higher residential proximity to truck routes, fewer infant and child care centers, and lack of geographically distributed primary care facilities.

Despite significant educational and advocacy efforts by CEHD in areas spanning social services, housing, comprehensive planning, health care, food security, and environmental health, a number of challenges remain in Galveston, particularly for the most vulnerable. For example, the hurricane reduced access to healthy food after several full-service grocery stores were flooded. Although Dr. Nolen and her colleagues documented the problem, especially for poor people, explored options with local community economic development groups, and highlighted the problem in the media, the problem remains unresolved. Public housing also remains an unresolved issue and has become a flashpoint for the community. Galveston’s public housing was badly damaged by the flooding and has yet to be rebuilt, despite CEHD’s advocacy regarding the benefits of mixed-income, mixed-use neighborhoods as an alternative to segregated neighborhoods. With rebuilding of public housing in limbo, the slower return of lower-income residents also appeared to impact overall recovery, including recovery of the local economy.

In terms of lessons learned, Dr. Nolen observed that one of the biggest problems is that recovery programs were not necessarily designed so as to have a positive impact on health. It was also difficult to coordinate funding streams for recovery. There were too many players at the table with divergent interests and not enough focus on healthy communities. Another important lesson was the value of preestablished relationships on which a HiAP approach should be built. CEHD was too new to have standing or a recognized role in the community when Ike struck the island. It took 2 years of frequent presentations at local planning meetings before the concept of a healthy community began to gain traction to the extent that community groups began seeking input from CEHD. Thus, pre-disaster planning and relationship building are essential to accelerating recovery and supporting a HiAP approach.

SOURCE: Nolen, 2014.

- partnering with decision makers and planners to incorporate evidence-based recommendations into the planning process by applying a health lens to the programs and services of other sectors (see Figure 2-3).

A primary barrier to the integration of health improvement strategies into the recovery process is the lack of data on return on investment. In the course of future disaster recovery efforts, it will be important to measure impacts on health outcomes.

A HiAP approach is ideally suited to ensuring that health considerations are incorporated into the recovery decision-making process across all sectors. However, further research is needed to better understand the facilitators of and barriers to a HiAP approach in the disaster recovery context.

SOURCE: B. Hokanson/PLN Associates.

The process of recovery from a disaster is well recognized to be a long one, often taking years. It is also a unique opportunity to address systemic issues that have multiple negative effects on communities in such areas as health, economic viability, and vulnerability. Although there appears to be growing emphasis on the incorporation of resilience-building efforts into the recovery process (spurred in part by the looming threat of climate change), the idea of simultaneously working to enhance the health of communities and their residents does not, unfortunately, appear to be widespread. Despite a growing healthy community movement outside of the disaster context, the committee noted only a handful of communities taking this forward-looking and synergistic approach to recovery. There are a number of reasons why the committee believes this approach should be adopted in a far more systematic way.

First, addressing the inequities that contribute to disparities in health is an ethical imperative. As stated by the World Health Organization’s Commission on the Social Determinants of Health, “social injustice is killing people on a grand scale” (CSDH, 2008, p. 26). The disruption caused by disasters may offer an

opportunity to change the physical, social, and economic environments that have stemmed from a legacy of unfair and discriminatory social policies. Beyond this ethical reason, however, is a national security reason: poor health and the social determinants of health contribute to social vulnerability in the disaster context. Disasters are unquestionable tragedies, but they are also an enormous burden for the communities they affect and the nation in which those communities reside. This burden manifests not only as financial but also social costs (e.g., the tearing of a community’s social fabric). Working to improve health and social well-being after a disaster needs to receive greater attention as a hazard mitigation process. This concept has much more weight outside of the United States in the context of disaster risk reduction. Finally, there is the issue of economic viability. Poor health indicators tend to cluster with other troubling and systemic problems for communities—issues such as blight, crime, and poverty. All can contribute to a negatively reinforcing cycle of disinvestment and economic decline, with rising, unsustainable health care and social service costs. Recovery offers an opportunity to infuse new vigor into declining communities. More livable and vibrant cities, towns, and neighborhoods will draw residents and businesses alike.