3

A Framework for Integrating Health into Recovery Planning

“Long-term recovery planning is an opportunity to improve a community’s quality

of life and disaster resiliency. It has the potential to inspire communities to set goals

beyond restoration of the status quo.”

—Boyd, 2014, p. 3

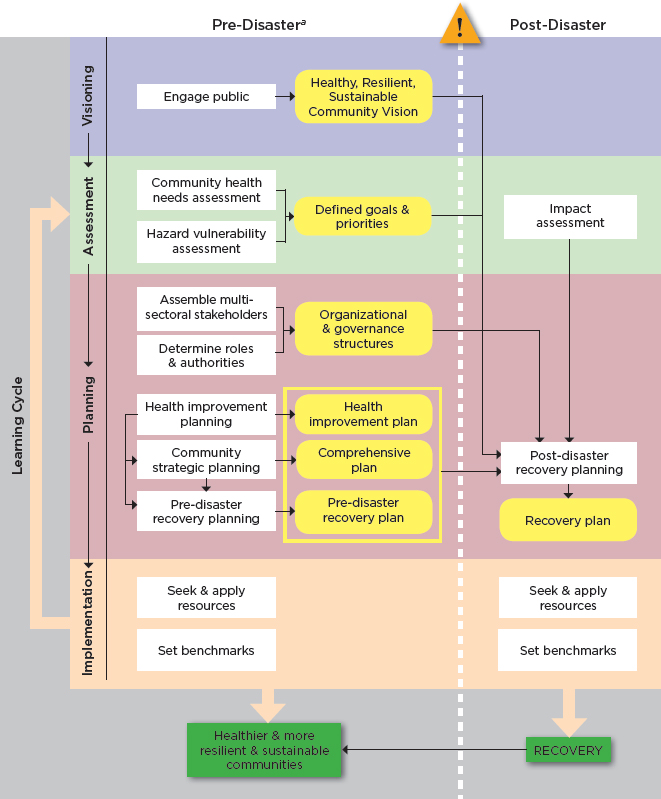

Disaster recovery is a process of strategic community planning, similar to that which takes place in communities throughout the country every day, except that it entails the enormous challenges of time compression: a process that would normally occur over decades must be carried out within a relatively short period of time (Olshansky, 2014). Beginning the recovery planning process before a disaster and leveraging the products of other community planning efforts can make post-disaster recovery planning more efficient and also better ensure that opportunities for community betterment (including health improvement) are not missed. In this chapter, the committee uses the strategic planning process as a framework for describing the opportunities and mechanisms for incorporating health considerations into the recovery planning process, both before and after a disaster. It should be emphasized that the intent here is not to provide a comprehensive description of the recovery planning process; such a description is beyond the scope of this study and has been provided elsewhere.1

THE STRATEGIC PLANNING PROCESS AS A FRAMEWORK

In strategic planning, quantifiable data and a process of systematic analysis are used to develop goals, identify alternatives, and establish criteria for decision making. Although there are slight variations and differences in terminology, the general structure of such planning processes (whether developing a comprehensive plan, health improvement plan, or disaster recovery plan) is similar. After an initial period

________________

1 Of note, in 2014 the American Planning Association released Planning for Post-Disaster Recovery: Next Generation, an update of its 1998 report on recovery planning (APA, 2014). The committee suggests this report as a useful resource for those desiring a more detailed description of the disaster recovery planning process. The report is available online at: https://www.planning.org/research/postdisaster (accessed March 13, 2015).

of laying the groundwork, there is often a visioning process and an assessment of community status and needs, assets, and contextual factors (e.g., political environment). The results of these two processes are used to establish goals and set priorities by comparing the findings of the assessment against the community’s vision to identify gaps between the current status within the community and the desired state. Strategies are developed to close the gaps through input from stakeholders (including the public) and analysis of alternatives. These strategies are incorporated into a plan, and implementation partnerships (or operational structures) are developed. Finally, the plan is implemented. Resources are identified and applied, and progress is continuously measured using preestablished benchmarks. Even if it is not possible to tackle each priority area initially, a prioritized list makes it possible to evaluate future opportunities to determine how they can be leveraged to achieve the community’s shared vision. Thus, the process of implementation feeds into a continuous cycle of assessment, planning, and implementation.

The strategic planning process, if successful, creates new channels for communication and builds consensus on the community’s greatest needs going forward. This consensus building is critical to keep decision makers focused on long-term strategic objectives rather than on reactionary responses to the crisis of the day. Thus, obtaining buy-in from leadership is an essential step in ensuring that the plan is acted upon.

In the context of integrating health into the disaster recovery planning process, each of the steps in the strategic planning cycle presents opportunities. These are summarized below and then described in more detail throughout this chapter. It should be emphasized that, although the process is presented as sequential for purposes of exposition, in reality the order of steps may be varied, and some may be undertaken simultaneously. For example, visioning may occur before, simultaneously with, or after an assessment process, and because the process is a continuous cycle, the implementation step feeds into a new assessment used to evaluate the impact of the activities undertaken.

- Visioning: Recovery is viewed as an opportunity to advance a shared vision of a healthier and more resilient and sustainable community.

- Assessment: Community health assessments and hazard vulnerability assessments provide data that show the gaps between the community’s current status and desired state and inform the development of goals, priorities, and strategies.

- Planning: Health considerations are incorporated into recovery decision making across all sectors. This integration is facilitated by involving the health sector in integrated planning activities and by ensuring that decision makers are sensitized to the potential health impacts of all recovery decisions.

- Implementation: Recovery resources are used in creative and synergistic ways so that the actions of the health sector maximize health outcomes and the actions of other sectors yield co-benefits for health. A learning process is instituted so that the impacts of recovery activities on health and well-being are continuously evaluated and used to inform iterative decision making.

Building on Previous Strategic Planning Processes

Rationale for the Integration of Planning Processes

In the post-disaster period, there is intense pressure from the residents of the community to return to a state of normalcy. As a result, attempts to address deficiencies in pre-event conditions (including health deficiencies and disparities) through post-disaster planning alone will be challenging and may not be successful. Thus, pre-disaster recovery planning is critical to seizing opportunities for improving community conditions beyond the pre-disaster state. After a disaster, the resources that become available to support recovery can then be evaluated against the preestablished goals for improvement of health and social vulnerability, and relationships developed through the planning process can be leveraged in developing strategies for achieving the community’s preestablished vision of a healthy, resilient, and sustainable community.

In most cases, communities (cities, counties, towns) that have been struck by a disaster already have strategic plans in place that were created to guide decision making related to long-term development and

investment. It follows that these plans would be consulted in the process of developing a recovery strategy so that the recovery process can help the community advance toward a previously agreed-upon vision and set of goals. Figure 3-1 shows how products from previous planning processes—including a shared vision, assessments, and plans—are optimally leveraged and built upon to guide the disaster recovery planning process.

Relevant to the purposes of this report, a community’s comprehensive plan,2 health improvement plan, sustainability plan, and mitigation plan—and, in some cases, its regional development plan—can yield health-related goals and investment strategies to inform the recovery planning process. Ideally, the community health improvement plan (following from a community health assessment) will have informed the development of the comprehensive plan. The decisions and strategies that are the domain of the comprehensive planning process—land use, transportation, housing—determine the nature of the physical and social environments in which people live. Planning decisions over the past century have had enormous impacts on some of the nation’s most intractable public health challenges, such as obesity, chronic respiratory diseases, health disparities, and mental health (Dannenberg et al., 2003; Frumkin et al., 2004; Ricklin et al., 2012). Consequently, the comprehensive planning process is an important mechanism for enacting change in arenas beyond the direct influence of the health sector, such as the design of the built environment (APA, 2006a).

The integration of a health-focused community vision and health improvement goals into the community strategic planning process and the comprehensive plan itself helps ensure buy-in from leadership (since these plans must be formally adopted by the community’s governing body) and subsequently the incorporation of these elements into recovery strategic planning. According to the American Planning Association (Schwab et al., 1998, p. 238), “Post-disaster recovery plans should be a specific application of the relevant portions of the community comprehensive plan, designed to deal with the constraints and opportunities posed by disaster conditions.” Thus, a community that has undertaken this integration before a disaster is likely to be better equipped to address health considerations during recovery. Similar approaches are being promoted for the purposes of resilience. The Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) now recommends the integration of hazard mitigation planning into the comprehensive plan as a means of ensuring that resilience is established as a community value and that hazard vulnerability is considered during all future development (FEMA, 2013a). According to the American Planning Association, “hazard mitigation works best as a policy objective of local planning when it is so completely integrated into the comprehensive plan that it becomes a normal assumption behind all daily planning activities” (Schwab et al., 1998, p. 61). The committee envisions the same outcome for health and social well-being.

The Current State of Integration of Planning Processes

Unfortunately, the committee found that the predominant model at present is one in which community comprehensive planning, health improvement planning, resiliency and sustainability planning, and disaster recovery planning occur largely in isolation. Barriers to integration noted by both public health and planning professionals include a lack of resources, tools, and guidelines, as well as an absence of qualified personnel able to bridge the two fields (APA, 2006a). In 2010, the American Planning Association surveyed planning departments across the United States to determine how comprehensive plans and sustainability plans are and can be used to protect and promote health. Just over a quarter of the nearly 900 respondents indicated that public health issues were addressed explicitly in their jurisdiction’s officially adopted comprehensive plan, either through stand-alone health planning elements or the incorporation of health concerns into other planning elements, such as land use (Hodgson, 2011). Common health topics in the examined plans included physical activity or active living, clean air and other environmental exposures, and public safety. However, there was a notable lack of focus on food and nutrition, health and human services, social

________________

2 The comprehensive plan, also known as the general plan, is the product of a community’s comprehensive planning process, which is used to determine community goals and aspirations for future community development.

a Although the committee strongly encourages communities to undertake these activities in the pre-disaster period to maximize opportunities for leveraging the post-event recovery process to create healthier and more resilient and sustainable communities, there is still benefit to incorporating them into post-disaster recovery planning if they have not been undertaken beforehand.

cohesion, and mental health (Ricklin and Kushner, 2013). A 2010 International City/County Management Association survey found that although many communities have a range of sustainability activities that address social equity (e.g., affordable housing, preschool programs, workforce development initiatives), only about one-third of the approximately 2,100 responding local governments considered social justice a priority, and few were organizing and resourcing sustainability-related programs in a coordinated way or incorporating them into the comprehensive plan (ICMA, 2014). The two studies together indicate that the social aspects of health are not yet a focus for most local governments and that much greater effort is needed to integrate all determinants of health into comprehensive plans.

Similarly, the committee found little evidence of integration of a healthy community vision and long-term health improvement goals into pre-disaster recovery plans. Unfortunately, few communities have taken a proactive approach to the development of comprehensive pre-disaster recovery plans (Community Planning Workshop, 2010; Smith, 2011b). Two recent publications highlight cases in which pre-disaster planning for recovery was undertaken (City of Seattle, 2013; Community Planning Workshop, 2010), both concluding that few models were available to guide communities in the development of such plans. This paucity of pre-disaster recovery plans is due in part to the lack of incentives for communities to undergo what can be a complex, time-consuming, and controversial process (Community Planning Workshop, 2010). To better understand the degree to which community health improvement goals have been incorporated into pre-disaster recovery planning, the committee reviewed available pre-disaster recovery plans and sought testimony from public health, emergency management, and city management representatives. These information gathering processes yielded the following findings:

- Approximately three-quarters of the roughly two dozen pre-disaster recovery plans examined3 explicitly address health considerations to some degree but are focused almost exclusively on short- and intermediate-term recovery activities (e.g., reopening and restoring health facilities; retaining medical personnel; ensuring access to pharmaceuticals; meeting the needs of vulnerable populations; providing mental health assistance; handling mass casualties; controlling disease outbreaks; and preventing exposure to unsafe materials such as debris, mold, and chemicals).

- Pre-disaster recovery plans that are more operational in nature (lay out organizational structures, roles, and responsibilities) focus primarily on short- and intermediate-term recovery activities with discussion of long-term recovery being limited to a return to pre-incident conditions/normal operations. Although these plans address increasing resilience through recovery activities (e.g., through hazard mitigation processes), the committee found no references to using the recovery process as an opportunity to build healthier communities. Plans that are more visionary in nature4 are more likely to reference opportunities to use the recovery process to create healthier post-disaster communities, although none of the plans examined mentions leveraging the community’s health improvement process. However, several plans recommend incorporating the vision and goals of the comprehensive plan, reinforcing the importance of integrating health improvement and comprehensive planning prior to a disaster (Hillsborough County Government, 2010; Pinellas County, 2012).

- Testimony of public health officials from jurisdictions that have been through a disaster was focused largely on short- and intermediate-term needs (e.g., restoring health care operations, ensuring access to pharmaceuticals), although testimony from the former health commissioner of New Orleans did include considerable discussion of strategies undertaken in that city to rebuild both public health

________________

3 It should be noted that the vast majority of these plans were from Florida counties. Florida has led the development of pre-disaster redevelopment plans, spurred in part by a statute requiring all coastal communities to have them (Section 163.3177(6)(g), Florida Statutes; Section 163.3178(2), Florida Statutes). The state developed a planning guide, the Web link to which can be found in Appendix C.

4 The redevelopment plans of Hillsborough County (Hillsborough County Government, 2010) and Pinellas County (Pinellas County, 2012) in Florida were found to be good models for ensuring that health and social well-being considerations are incorporated into diverse aspects of recovery planning. Links to these plans are available in Appendix C.

-

and health care systems in a way that would improve the health of the community (DeSalvo, 2013). The testimony of urban and regional planners was more likely to include discussion of opportunities to build the community back in a way that promotes health—perhaps reflecting growing interest in health within the urban and regional planning and design fields since many of the opportunities to change the physical and social environments of a community fall under the purview of planning professionals.

- Health departments find leveraging the recovery process for long-term health improvement challenging because of their intense mission focus on response activities, the lack of funding to support long-term recovery projects, their lack of engagement in community long-term recovery planning, and the perception that a discussion of such topics as long-term health improvement strategies would not be well received by a community still dealing with significant acute post-disaster needs (Beardsley, 2014; Clements, 2014; Zucker, 2014).

- Although federal preparedness funds available from both the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response within the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) are eligible for use to support recovery planning, there is currently little emphasis on using the recovery process for long-term community health improvement (Blumenstock, 2014; Shah, 2014).

- Nearly all communities in the nation are recipients of federal community development funding, and a large proportion of these local governments are using the targeted funds to revitalize troubled neighborhoods and address the needs of residents—efforts essentially similar to those of disaster recovery. Nonetheless, there is low awareness of pre-existing community development endeavors during the preparation of pre-disaster recovery and hazard mitigation plans.

In summary, based on the testimony of a diverse set of stakeholders, including the public health community, and a review of available recovery plans, the committee finds that a healthy community vision rarely guides the development of pre-disaster and post-disaster recovery plans. As a result, a health lens is not applied to the process of decision making regarding the allocation of recovery resources, and unique opportunities are being missed. The following four gaps impede the development of plans to “build back better,” and specifically in ways that contribute to an overall healthier community:

- inadequate pre-disaster community health improvement planning (not being done at all, or not using a process that engages the full range of community stakeholders in addressing the comprehensive physical and social determinants of health);

- inadequate integration of health improvement planning and the community comprehensive (strategic) planning process used to set priorities and allocate funds;

- lack of integration of health improvement planning and disaster recovery planning;

- insufficient awareness across all sectors of the health-related threats and opportunities posed by disasters and of the benefits to be gained from integrating community health improvement objectives and priorities into comprehensive and disaster recovery plans to achieve shared goals.

In some cases, these gaps reflect long-standing silos within and among institutional arrangements and staffing structures. Enhanced collaboration across sectors offers an opportunity to align planning processes around a shared vision and goals so as to optimize community health and social service outcomes during recovery. Table 3-1 illustrates potential roles for diverse community stakeholders in this integrative process. For the most vexing problems, however, especially where large-scale community revitalization is at stake, solutions may require significant leadership investment to achieve organizational readiness and the capacity for synergistic, multisector health-sensitive disaster recovery planning.

TABLE 3-1 Collaborative Roles of Sector and Community Stakeholders in the Integration of Strategic Planning Processesa to Achieve Healthier and More Resilient and Sustainable Post-Disaster Communities

| Visioning | Assessment | Planning | Implementation | ||||||

| Task | Educate community on elements of healthy, resilient, and sustainable communities | Conduct community health assessments, ensuring that Internal Revenue Service (IRS)required hospital Community Health Needs Assessments (CHNA) are integrated | Develop health improvement plan based on health assessment | Exercise pre-disaster recovery plan by practicing organizational arrangements suited to hypothetical disasters | |||||

| Lead(s) | Public health, emergency management, urban and regional planning | Public health, health care | Public health | Emergency management | |||||

| Partners | All sectors, all stakeholders, community members | Social services, behavioral health | All sectors | All sectors | |||||

| Whenb | |||||||||

| Task | Conduct community visioning process | Assess vulnerability of critical infrastructure | Develop comprehensive plan, ensuring inclusion of all relevant plans (e.g., hazard mitigation, health improvement, economic, redevelopment) | Adopt regulations, incentives, programs, budgets, and community outreach to achieve community vision and goals | |||||

| Lead(s) | Urban and regional planning, public health | Public health, public works, emergency management, facility management, planning | Urban and regional planning | Chief executive, community managers, elected governing body | |||||

| Partners | All other sectors | Management, finance, budget | Public health, emergency management, other local agencies | All implementing agencies and organizations | |||||

| Whenb | |||||||||

| Task | Incorporate community vision into comprehensive planning process | Identify areas with large socially vulnerable populations | Plan organizational structures for postdisaster coordination of activities | Seek methods for making optimum use of technology and information systems for both public outreach and pre-disaster policy analysis | |||||

| Lead(s) | Urban and regional planning, public health, environmental health, social services | Public health, urban and regional planning, emergency management, social services | Emergency management | Emergency management, public health, urban and regional planning | |||||

| Visioning | Assessment | Planning | Implementation | ||||||

| Partners | All sectors, plus management, finance, budget offices | Research organizations, community groups, neighborhood associations, health and medical system partners | All sectors | All sectors | |||||

| Whenb | |||||||||

| Task | Ensure that pre-disaster recovery plan incorporates community-developed vision of healthy, resilient, sustainable community | Periodically assess effectiveness of institutional arrangements that promote cross-sector collaborations and joint mitigation activities | Develop pre-disaster recovery plan | Establish joint communications center; facilitate information exchange on community recovery needs | |||||

| Lead(s) | Emergency management, urban and regional planning | Emergency management, urban and regional planning, public health | Urban and regional planning, economic development agency, emergency management | Emergency management, public officials | |||||

| Partners | Public health and other agencies | Education system, health and medical system partners, business representatives | All sectors | Public health, health care, behavioral health, social services | |||||

| Whenb | |||||||||

| Task | Periodically revisit community vision statements for relevance in light of changing conditions and altered vulnerabilities | Assess unmet social needs, pre- and postdisaster | Conduct health impact assessments to inform recovery planning | Develop recovery finance strategy, determine funding eligibility, apply for funds, administer grants | |||||

| Lead(s) | Urban and regional planning, public health, emergency management | Social services | Public health | Designated recovery manager | |||||

| Partners | All sectors, plus management, finance, budget offices | Public health, behavioral health, emergency management | All sectors | All sectors | |||||

| Whenb | |||||||||

| Task | Monitor economic development and community development initiatives that may strengthen the community, add resilience, create sustainability | Conduct postdisaster assessment of disaster impact on infrastructure and systems | Develop post-disaster recovery plan | Carry out recovery projects and programs; arrange project and program management | |||||

| Visioning | Assessment | Planning | Implementation | ||||||

| Lead(s) | Urban and regional planning, public health, emergency management | Emergency management | Emergency management, urban and regional planning | All sectors | |||||

| Partners | All sectors, plus management, finance, budget offices | Urban and regional planning, public works, public health, management | All sectors | Management departments such as budget, finance, legal services | |||||

| Whenb | |||||||||

a The processes to be integrated include community comprehensive planning, health improvement planning, mitigation/ resilience planning, and disaster recovery planning.

b 1 = pre-disaster; 2 = response and short-term recovery; 3 = long-term post-disaster recovery. Coloring of the symbols indicates urgency: red = priority; black = possibility.

A HEALTHY, RESILIENT, SUSTAINABLE COMMUNITY VISION FOR DISASTER RECOVERY

Disasters, although devastating, create an opportunity through the recovery process to advance a shared vision of a healthier and more resilient and sustainable community. In Chapter 2, the committee describes the elements of a healthy community and its linkages with the concepts of equity, resilience, and sustainability. How these elements are incorporated into the shared vision for an individual community needs to be defined as an integral part of community strategic planning processes conducted before an event, so that a clear vision is in place to drive post-disaster decision making as new resources become available and opportunities arise. Otherwise, pressure to rebuild quickly after a disaster may result in missed opportunities.

A common vision for recovery is highlighted by FEMA (2011c) as one of eight major components of a successful recovery in Lessons in Community Recovery, a 2011 report that presents lessons learned from 7 years of experience with the long-term community recovery emergency support function. A vision provides a “beacon for decision makers and some framework within which decisions will be taken” (Schwab et al., 1998, p. 47). Without an overall vision, goals and objectives often are disconnected from each other and from a larger purpose. A community’s vision becomes the foundation for subsequent policies and regulatory changes, and investments. A visioning process also can drive enthusiasm and provide a foundation for creative collaboration. It is not surprising, then, that many planning processes, including disaster recovery planning, begin with a visioning process that defines a desired future state.

The Importance of Having a Vision and Goals in Place Before a Disaster

Visioning is a common early step in the recovery planning process after a disaster. As the committee learned through testimony from disaster recovery experts and from a review of case studies, however, a community that has already gone through the process of envisioning its future and setting measurable goals and priorities before a disaster is in a better position to converge on a plan for recovery quickly after such an event (see Box 3-1). The urgency of the post-disaster period poses a significant challenge to the development of recovery plans that meet a community’s long-term needs. Governments facing the complex

BOX 3-1

The Value of Pre-Disaster Visioning and Planning: A Tale of Two Cities

The New Orleans Experience

The flooding of New Orleans that resulted from levee failure after Hurricane Katrina struck the Gulf Coast in 2005 is among the most catastrophic disasters in U.S. history. The recovery process in New Orleans continues today and was significantly impeded by disputes over processes and goals for reconstruction, with tensions arising from conflicting desires to quickly rebuild the familiar or to create a safer and more sustainable and equitable city (Kates et al., 2006). In many cases, ideas for reducing the size of the city and increasing green space were viewed as efforts to get rid of predominantly African American and low-income neighborhoods (Colten et al., 2008). Although the recovery planning process was initiated shortly after the flood, it took nearly 2 years and multiple rounds of planning initiated independently by the state and city to develop an officially accepted plan (the Unified New Orleans Plan). Despite these delays, the city of New Orleans has seized on the opportunities presented by disaster recovery to build back better. A 2010 update of the city’s comprehensive plan, Plan for the 21st Century: New Orleans 2030, includes as goals livability, opportunity, and sustainability (Collins, 2011).

The Cedar Rapids Experience

On June 13, 2008, the Cedar River, which flows through Cedar Rapids, Iowa, rose a record-setting 30+ feet, causing significant flooding in the city. Although no deaths resulted, the flood caused widespread destruction of the city’s physical infrastructure and resulted in the displacement of more than 10,000 residents. Fortuitously, the city council and city manager had initiated a broad community engagement effort just months before the flood to develop a shared vision for the community’s future (CARRI and CaRES, 2013). This existing engagement process, the resultant community vision, and a related effort to adopt a systems approach to government operations all enabled the community to come together quickly after the flood around a plan for what their new community would look like. The recovery plan, which incorporated input from thousands of residents, included such goals as encouraging active, healthy lifestyles; ensuring equitable redevelopment; building resource-efficient and resilient buildings; and protecting the city against future floods by rebuilding outside of flood-prone areas (ULI, 2014). Cedar Rapids has been recognized for its success by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, the American Planning Association, and the International Downtown Association, and it is touted as a model for other communities because of its ability to rapidly develop a publicly supported recovery plan that will create a better, safer future for all of its residents (CARRI and CaRES, 2013).

process of reconstruction after a disaster must balance two competing priorities—speed and deliberation (Johnson and Olshansky, 2013). Tensions inevitably arise between the need to restore infrastructure and a sense of normalcy as quickly as possible and the desire to leverage the recovery process as an opportunity for community betterment. Without a preexisting vision and associated goals, reactive decision making early in the recovery period may severely limit the range of options for betterment during later recovery phases. Accordingly, the phrase “window of opportunity” often is associated with the short period of time immediately after a disaster. As expressed by Jennifer Pratt, assistant director of planning services for the city of Cedar Rapids, Iowa, “One thing we heard from other communities that had suffered natural disasters was that it was important to have a plan rather quickly, because people naturally become nostalgic and just say, ‘Well, I want it the way it was before’” (ULI, 2014, p. 21).

Communities undertake a number of planning processes that yield a shared vision for the future that could be incorporated into pre- and post-disaster recovery planning efforts. A disaster should not change the long-term vision for a community, just the steps for achieving it. Plans that should be examined (if

available) include a community’s comprehensive plan, health improvement plan, and sustainability plan. If a holistic vision for a healthy, resilient, sustainable community is lacking, however, the pre-disaster recovery planning process can be used to build on previous visioning efforts. Using the shared vision as a guide, action plans can be developed after a disaster based on the new social, economic, and environmental conditions of the community (ASTHO, 2007).

Creating a Shared Vision as a First Step in Engaging the Public in Disaster Recovery

The involvement of informed and empowered individuals and communities through an authentic community engagement process is nearly universally recognized as a factor in the success of any community planning endeavor, including healthy community planning and disaster recovery (FEMA, 2011c; Love and Vallance, 2014). Community engagement has been defined as “the process of working collaboratively with and through groups of people affiliated by geographic proximity, special interest, or similar situations to address issues affecting the well-being of those people” (CDC, 1997, p. 9). “With and through” are the key words in this definition. Community engagement entails more than extracting information from residents about their needs and wants. True engagement integrates the affected community into every aspect of a project, from identifying needs to selecting priorities to implementing programs. Thus, there should be an “ongoing dialogue among residents to build relationships and a shared vision of what the community is, what it should be, and how to get there” (Norris and Pittman, 2000, p. 121).

The visioning process is an opportunity for communities to begin to rectify a legacy of exclusion that has contributed to the significant disparities apparent across U.S. communities today. Consequently, it is essential that groups representative of all members of the community—including the most vulnerable populations—be involved in the planning process, thus ensuring that the voices, perspectives, and needs of all segments of the community are addressed. Vulnerable populations often have special needs during and after a disaster, but they continue to be excluded from disaster planning processes (Sherry and Harkins, 2011). For example, low-income residents displaced by a disaster may not be able to return to the community as easily as their higher-income neighbors. Because of their absence, their voices are not heard at meetings and their perspective is not taken into account when rebuilding is being planned. In Galveston, Texas, this scenario led to a harsh outcome for low-income residents (Nolen, 2014). After 569 public housing units on the island were demolished following Hurricane Ike, many locals, including city council members, fought vigorously not to rebuild them. Community advisory committees that were providing input on recovery plans were limited to residents who were living in Galveston after the disaster, thus excluding anyone who had not yet returned. It took state and federal intervention to finally spur rebuilding of the units, a full 6 years after the hurricane struck (Rice, 2014). Had there been an attempt to include the displaced low-income residents in the crafting of the recovery plan, their voices would have been heard, and the public housing might have been rebuilt much more quickly.

Means of engaging the community in visioning often include town hall meetings, public workshops, surveys, and charrettes.5 Some activities undertaken while laying the groundwork for planning can help ensure the success of the visioning process. These activities may include but are not limited to

- identifying and engaging local health champions (from health and nonhealth sectors) to facilitate discussions;

- identifying other previous efforts and experiences that are relevant; and

- conducting health literacy efforts and educating the community on the elements of and benefits to healthy, resilient, and sustainable communities.

________________

5 A charrette is an iterative process that is often used to exchange ideas between urban and regional planners/designers and the community, resulting in an evolving series of designs (APA, 2006b).

ASSESSMENTS TO INFORM RECOVERY PLANNING

An assessment process is undertaken to inform the strategic approach to community planning. This process can be used to identify the needs, assets, and capacities of the community; prioritize interventions; and provide a baseline against which change can be measured. Three common assessments of relevance to disaster recovery planning are community health assessments, threat and hazard identification and risk assessments, and disaster impact assessments (see also the discussion of health impact assessments later in this chapter).

A community health assessment (sometimes referred to as a community health needs assessment) is “a systematic examination of the health status indicators for a given population that is used to identify key problems and assets in a community” (PHAB, 2011, p. 8). Community health assessments are part of a strategic planning process for health improvement, such as that described by the Mobilizing for Action through Planning and Partnerships (MAPP) framework (Lenihan, 2005). MAPP was developed to enable communities to “seek to achieve optimal health by identifying and using their resources wisely, taking into account their unique circumstances and needs, and forming effective partnerships for strategic action” (NACCHO, 2014c). Communities that use MAPP carry out a six-phase process: organizing, visioning, assessments, strategic issues, goals/strategies, and action cycle (NACCHO, 2014d). Although the collection of traditional health status indicators (e.g., obesity rates, numbers of uninsured) is an important part of the assessment process, it is necessary to adopt a more holistic approach. Other information relevant to a community health assessment may include community perceptions regarding health and quality of life, the performance of the local health system, and an evaluation of factors influencing health in the community (e.g., policies). Conducting a more comprehensive community health assessment to include these additional elements will provide a more complete understanding of the factors that influence community health (NACCHO, 2014b). Another valuable tool for community health assessment is the Community Health Needs Assessment Toolkit from Community Commons, an online tool that consolidates data from multiple sources and enables users to create maps and reports of health indicators (Community Commons, 2014).

Many local health departments, as well as nonprofit hospitals, are conducting community health assessments and leveraging them in the development of community health improvement plans. Health improvement planning is a requirement for public health agency accreditation, and under the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA), the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) requires nonprofit hospitals to conduct a community health needs assessment (CHNA) at least once every 3 years as a condition for retaining tax-exempt status.6,7 Data from the 2013 National Profile of Local Health Departments indicate that within the past 5 years 70 percent of local health departments conducted a community health assessment, and more than half (56 percent) completed a community health improvement plan (NACCHO, 2014a). While the committee found these data encouraging, it is unclear how many of these plans have been successfully implemented. The suboptimal status of nationwide health statistics indicates that despite these increased planning initiatives, problems with implementation remain. Further, there is little evidence to suggest that these plans are aligned with broader community strategic planning processes such as those associated with the development of comprehensive or sustainability plans. As a result, the goals developed in those planning processes may not be sufficiently understood by the key community leaders and officials who are typically responsible for managing disaster recovery and, thus, may not be identified as priorities or leveraged during the recovery planning process.

________________

6 Under a final regulation effective as of December 29, 2014, a charitable hospital must (1) define the community it serves; (2) assess the health needs of that community; (3) take into account input from representatives of the community, including those with expertise in public health; (4) document the community health needs assessment in a written report; and (5) make that report available to the public (See 79 F.R. 78953, Dec. 31, 2014.)

7 79 F.R. 78953, Dec. 31, 2014.

Threat and Hazard Identification and Risk Assessments

Disaster recovery planning should be based on an assessment of locally specific risks. The threat and hazard identification and risk assessment process (described in Box 3-2) is a valuable tool for communities, helping them answer the following key questions as part of the pre-disaster planning process: “What do we need to prepare for, what sharable resources are required in order to be prepared, and what actions could be employed to avoid, divert, lessen or eliminate a threat or hazard?” (FEMA, 2014d). The assessment process is a community-wide initiative that emphasizes anticipation prior to assessment. As part of this process, community members themselves identify threats and hazards of concern and place them in the context of the greater community (FEMA, 2013b). The community then assesses each risk in context, developing capability targets and estimating the resources needed to achieve these targets for each of the core capabilities identified in the National Preparedness Goal. The use of community-level assessments, as opposed to traditional top-down assessments, reflects the fact that disasters and their impacts are unique to a given community and results in a more specific and informative assessment process overall. Internationally, the use of such community-level assessments has resulted in accelerated response and recovery (Reaves et al., 2014). Australia, for example, has expanded community-level input to its hazard anticipation and assessment as part of its Prepared Community model (Reaves et al., 2014).

Included among the capabilities under the National Preparedness Goal is Health and Social Services, as well as numerous other capabilities that impact a community’s health, such as Community Resilience, Long-Term Vulnerability Reduction, Risk and Disaster Resilience Assessment, Environmental Response/ Health and Safety, and Mass Care and Infrastructure Services. The Health and Social Services capability focuses on the ability to “restore and improve health and social services networks to promote the resilience, independence, health (including behavioral health), and well-being of the whole community” (FEMA, 2014a). Consequently, a community health assessment may inform the Threat and Hazard Identification and Risk Assessment process, particularly with regard to social vulnerability (discussed in Chapter 2), and there may be benefit to better integrating these two processes. Similarly, health care organizations are required to conduct a hazard vulnerability analysis as part of the accreditation process. These analyses help health care stakeholders prioritize risks so that appropriate planning, prevention, response, and recovery actions can be taken (The Joint Commission, 2005). The hazard vulnerability analysis provides an interface between the health care and emergency management sectors and should be complementary to the Threat and Hazard Identification and Risk Assessment process.

BOX 3-2

The Threat and Hazard Identification and Risk Assessment Process

- Identify Threats and Hazards of Concern: Based on a combination of experience, forecasting, subject matter expertise, and other available resources, identify a list of the threats and hazards of primary concern to the community.

- Give the Threats and Hazards Context: Describe the threats and hazards of concern, showing how they may affect the community.

- Establish Capability Targets: Assess each threat and hazard in context to develop a specific capability target for each core capability identified in the National Preparedness Goal. The capability target defines success for the capability.

- Apply the Results: For each core capability, estimate the resources required to achieve the capability targets through the use of community assets and mutual aid, while also considering preparedness activities, including mitigation opportunities.

SOURCE: Excerpted from FEMA, 2013b.

In the aftermath of a disaster, a disaster impact assessment can help determine what damage the disaster has caused, providing public officials and emergency management with information about the needs of an affected community. The assessment includes not just damage to infrastructure but all of the needs of the community. As part of this assessment, interview teams comprising staff and volunteers from state, local, and regional health departments conduct community-specific surveys. Officials can then use this information to identify what resources are needed and to target specific warnings to affected residents (IOM and NRC, 2005).

The disaster impact assessment helps identify unmet health needs. It is important that such assessments be conducted periodically throughout the response and recovery process following a disaster. Such reassessment provides real-time information about the status of various health-related factors such as housing, mental health, and utilities services. As response and recovery activities progress, the health needs of a community may change, especially if migration of families takes place into or out of an affected community (IOM and NRC, 2005). Conducting a disaster impact assessment immediately after a disaster and then reassessing throughout the recovery process enables continuous monitoring of how a disaster has impacted and continues to impact the health of a community.

Among the keys to successful community recovery identified by FEMA are preparing (establishing roles and responsibilities) and actively planning (FEMA, 2014b). As emphasized throughout this report, depending on the nature of the disaster, recovery initiatives present a multitude of opportunities to build the community back better (healthier and more resilient and sustainable). But arranging the planning process itself is complicated, and the inclusion of public health, medical, and social services requires that additional consideration and effort be devoted to crafting creative solutions that meet multiple needs. Resources must be harnessed in a coherent fashion matched to the situation in the community, incorporating both the current status and the prior developments that will be the foundation for future progress. Blending new features into community systems after a disaster, including consideration of socioeconomic and physical environments, is a significant design challenge: creative solutions and synergistic perspectives are required in deciding what can be rearranged, identifying institutional resources to accompany this redesign, building stronger, mitigating hazards, and incorporating an emphasis on health and social services for better outcomes. The goal is better recovery by all measures, a more vital community where resilience and stability add to overall well-being—a healthy community in the fullest sense.

In Chapter 2, the committee describes Health in All Policies as “an approach to public policies across sectors that systematically takes into account the health implications of decisions, seeks synergies, and avoids harmful health impacts, in order to improve population health and health equity” (WHO, 2013), and it presents a rationale for the relevance of this approach to the recovery context. Operationalizing Health in All Policies in the disaster recovery context entails (1) creating organizational structures that optimally enable the coordination of efforts and the creation of synergies whereby core missions of nonhealth sectors align with healthy community objectives, and (2) ensuring that information on the potential health impacts of recovery decisions is available to the decision makers within those structures. Each of these requirements is described in the sections below.

Organizing for an Integrated Approach

Communities are complex adaptive systems8 where decision making is distributed and myriad cross-sector interdependencies exist (Olshansky, 2014). Organizational structures influence the siloing of related

________________

8 Complex adaptive systems (1) are nonlinear and dynamic, (2) are composed of independent agents whose goals and behaviors may conflict, (3) are self-organizing, learning systems, and (4) have no single point of control (Rouse, 2000).

services and functions that can impede potential synergies and co-benefits. Despite the clear importance of an integrated approach (as discussed in Chapter 2), the committee consistently learned, through testimony (Nolen, 2014) and its review of the disaster literature (Johnson and Olshansky, 2013), about the inefficiencies and challenges during recovery related to a lack of coordination. As a result, resources are not used effectively and people suffer unnecessarily, especially those who were most vulnerable prior to the disaster. The resulting delays in individual and community recovery impact all facets of community life, including the health of the population, social cohesion, and economic viability. The committee concludes that disaster recovery and ultimately the health of the community would be improved by the development of organizational structures that support

- integrating horizontally across sectors and agencies;

- integrating vertically from the federal to the local level;

- integrating across phases of the disaster continuum, from pre-event planning to long-term recovery; and

- integrating health considerations into recovery planning and practices.

The new national framework describing a governance structure for disaster recovery—the National Disaster Recovery Framework (NDRF)—if implemented effectively, provides a structure for addressing all four of these dimensions of integration. As discussed below, however, some challenges remain.

The National Disaster Recovery Framework: A Structure for Integration

The NDRF, released in 2011, provides a guide for the federal government to facilitate effective recovery at the community level (FEMA, 2011d). The NDRF grew out of recognition of the failure to plan for recovery after Hurricane Katrina, the failure to link local needs with available resources, and the failure to plan for the actions of multiple parties to address disagreements about resource allocation (Smith, 2011a). In 2006, Congress passed the Post-Katrina Emergency Management Reform Act,9 which mandated the development of a national recovery strategy by the federal government. Spearheaded by FEMA and its federal partners, the NDRF is not an explicit plan; rather, it is a framework document that defines how federal agencies should organize and operate during recovery to support states, tribes, and localities. It defines “core recovery principles; roles and responsibilities of recovery coordinators and other stakeholders; a coordinating structure that facilitates communication and collaboration among all stakeholders; guidance for pre- and post-disaster recovery planning; [and] the overall process by which communities can capitalize on opportunities to rebuild” what the NDRF asserts are “stronger, smarter, and safer” communities (FEMA, 2011d, p. 1). As discussed below, the NDRF is intended for a wide audience of governmental, nongovernmental, and private organizations with expertise spanning all sectors.

Recovery roles and responsibilities under the NDRF The NDRF supports a whole-community approach to disaster recovery. Emergency management has historically been a strongly government-led enterprise. However, there has been increasing recognition that a solely government-driven approach cannot adequately meet the complex and unique needs of an individual community preparing for, responding to, and recovering from a disaster (FEMA, 2011a). Nongovernmental partners play critical roles in the restoration of the “social and daily routines and support networks” that promote health, well-being, and resilience after disasters (Chandra and Acosta, 2009, p. ix). However, these roles have been poorly represented in state and federal policy, and inadequate attention has been paid to the impacts of policy and guidance issued by federal agencies on nongovernmental entities. Within the past 5 years, FEMA has sought to foster a new philosophical approach based on the “whole community” (FEMA, 2011b). Through stakeholder engagement processes, the agency identified three core principles that drive its whole-community approach:

________________

9 Post-Katrina Emergency Management Reform Act of 2006, 109th Cong., S.3721 (October 4, 2006).

- Understand and meet the actual needs of the whole community.

- Engage and empower all parts of the community.

- Strengthen what works well in communities on a daily basis (FEMA, 2011a, pp. 4-5).

The objective is to perform emergency management functions in a manner that integrates needs, capabilities, and resources across the whole community and to empower the community—government, the nonprofit sector, and the private sector—to work together as partners (CDC and CDC Foundation, 2013). Roles for specific groups are outlined below.

- Individuals and households: The NDRF envisions that individuals and households need to be prepared to sustain themselves immediately after a disaster by carrying adequate insurance; holding essential supplies of medication, food, and water; and listening to public information announcements on the recovery process.

- Local government: Local government plays a central role in planning and managing all phases of a community’s recovery. When local governments are overwhelmed by their responsibilities, they seek the services of state and federal governments. Local governments also galvanize the preparation of hazard mitigation and recovery plans, raise hazard awareness, and educate the public prior to and during the recovery process.

- State government: The states are central players in coordinating recovery activities, including the provision of financial and technical assistance. One type of financial assistance entails issuing bonds for building critical infrastructure. States often manage federal resources and are conduits to local and tribal governments.

- Federal government: The central role of the federal government is to facilitate the efforts of state and local governments to leverage needed resources to rebuild communities. The federal government can use the NDRF to recruit and engage available department and agency capacities to promote local recovery. Federal support must be scalable and adaptable to meet community needs.

- The nonprofit sector: The nonprofit sector encompasses faith-based and other volunteer community organizations, charities, foundations and philanthropies, professional associations, and academic institutions. Major roles of the nonprofit sector include case management, volunteer coordination, behavioral health and psychological support, housing repair, and construction. Nonprofits tend to fill the gaps when governmental services and support do not meet a community’s comprehensive needs. Nonprofits often conduct advocacy for community members.

- The private sector: The private sector plays an essential role by retaining and providing employment and a stable tax base. It also owns and operates much of the country’s infrastructure, including electrical power, financial, and telecommunications systems. The private sector, including utilities, banks, and insurance companies, can foster mitigation and encourage community resilience. Public–private partnerships are critical resources during recovery and facilitate the coordinated leveraging of funding from multiple sources (FEMA, 2011d).

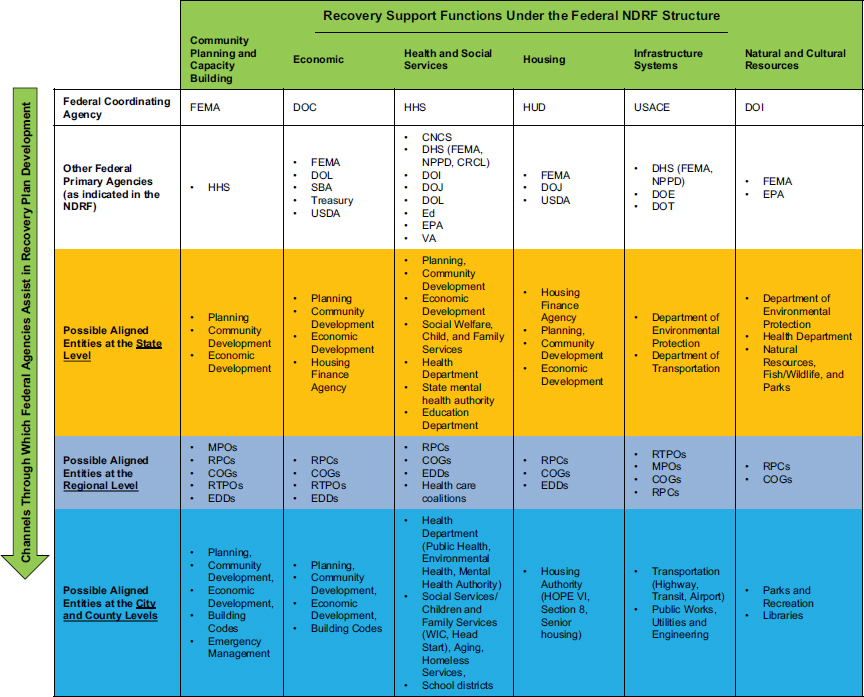

Recovery support functions Similar to the Emergency Support Functions (ESFs) defined by the National Response Framework,10 the NDRF defines six Recovery Support Functions (RSFs): Community Planning and Capacity Building; Economic; Health and Social Services; Housing; Infrastructure Systems; and Natural and Cultural Resources (described in more detail in Box 3-3). The RSFs help define an organizational

________________

10 The National Response Framework (NRF), also produced by FEMA, directs how the nation responds during the immediate period following all types of disasters and emergencies, ranging from “those that are adequately handled with local assets to those of catastrophic proportion that require marshaling the capabilities of the entire Nation” (FEMA, 2013c, p. 4). It “describes the principles, roles and responsibilities, and coordinating structures for delivering the core capabilities required to respond to an incident and further describes how response efforts integrate” with those of other related areas. Its objectives “define the capabilities necessary to save lives, protect property and the environment, meet basic human needs, stabilize the incident, restore basic services and community functionality, and establish a safe and secure environment moving toward the transition to recovery” (FEMA, 2013c, p. i).

structure for recovery operations that can promote vertical integration if aligned with structures created by state and local governments11 (see Figure 3-2). For each RSF, the NDRF specifies a federal coordinating agency, primary agencies, and supporting organizations. The coordinating agency furnishes leadership, coordination, and oversight. The primary agencies bring significant authorities, capabilities, roles, or resources to bear, but to a lesser extent than the coordinating agency. Supporting organizations, some of which are nongovernmental organizations, have specific capabilities or resources that complement those of the primary agencies. It should be noted that not all RSFs will be activated for all presidentially declared disasters; rather, decisions on RSF activation will be based on a post-disaster assessment of damage and needs. Existing pre-event recovery plans that delineate clear operational structures consistent with the NDRF, such as those of Fairfax County, Virginia, and Pinellas County, Florida, may be useful models (see Appendix C for links to these documents).

As the response period abates, emergency support functions will transition operations over to the RSFs, facilitating integration across disaster management phases. For example, responsibility for health and medical functions will transition from ESF #8 (Public Health and Medical Services) to the Health and Social Services RSF. Although there may be overlap in required expertise in the transition from response to early recovery, later recovery phases will necessitate the involvement of RSF representatives with different expertise, consistent with a transition from emergency functions to long-term reconstruction and community betterment activities. For example, transportation sector representatives supporting the Infrastructure Systems RSF should be those familiar with long-range transportation planning. For the health sector, the Health and Social Services RSF should include representatives working on an everyday basis to create healthier communities through community health improvement and social services activities. It is important to have clear plans in place for this transition and mechanisms for bringing in those trained in long-term community planning.

The NDRF also calls for three new leadership positions to monitor and coordinate disaster recovery through both the pre-disaster and the post-disaster period:

- A local disaster recovery manager who, among his/her many responsibilities, organizes the recovery planning process; ensures inclusiveness; develops and implements recovery progress measures; and communicates and coordinates with state, federal, and community stakeholders.

- A state disaster recovery coordinator leads statewide agencies by managing the recovery and by providing support for local initiatives. The state disaster recovery coordinator coordinates state, tribal, and federal funding streams; identifies gaps; and works collaboratively with recovery leadership at all levels to ensure a well-coordinated, timely, and well-executed recovery.

- A federal disaster recovery coordinator is responsible for facilitating recovery coordination and collaboration among all stakeholders. He/she monitors state and local decision making, evaluating the need for additional assistance. During the transition from response to recovery, coordination responsibilities will transition from the federal coordinating officer (who operates under the National Response Framework) to the federal disaster recovery coordinator.

The local disaster recovery manager, state disaster recovery coordinator, and federal disaster recovery coordinator facilitate vertical integration from the local to the federal level (FEMA, 2011c).

________________

11 Substate, regional organizations (e.g., Councils of Government, Metropolitan Planning Organizations, Regional Planning Commissions, Economic Development Districts) should also be considered in alignments with the federal NDRF structure since many states are organized into regional districts that are defined by a unified geography—established by state legislation—for diverse functions, both as regional entities with governing boards and as operating units of state agencies. These intergovernmental structures are key to organizing effective post-disaster community recovery. One example of a regional social service organization is an Area Agency on Aging. Such operations are often managed by Councils of Government or Regional Planning Commissions, offering a wide range of support services to senior citizens—who are often particularly vulnerable to the effects of disasters—including nutrition (Meals on Wheels, for example), transportation, and access to community programs.

BOX 3-3

Recovery Support Functions

Community Planning and Capacity Building

Coordinating Agency: DHS/FEMA

Primary Agencies: DHS/FEMA, HHS

The mission of this RSF is to promote and build recovery capacity and community planning resources for managing and implementing disaster recovery activities. This RSF assists States in developing pre- and post-disaster systems of support for local communities. This can be achieved in part by providing technical assistance and planning support to aid all levels of government to integrate sustainability principles—such as adaptive reuse of historic properties, mitigation considerations, smart growth principles, and sound land-use—into recovery decisions.

Economic

Coordinating Agency: DOC

Primary Agencies: DOC, DHS/FEMA, DOL, SBA, Treasury, USDA

Supporting Organizations include HHS

The mission of the Economic RSF is to help state, local, and community stakeholders to sustain and/or rebuild businesses and employment, as well as to develop economic opportunities that yield sustainable and economically resilient communities. This mission is achieved by leveraging federal resources, information, and leadership. The key is to encourage private investment and facilitate private sector lending and borrowing for restoring vital markets and economies.

Health and Social Services

Coordinating Agency: HHS

Primary Agencies: HHS, CNCS, DHS (FEMA, NPPD, CRCL), DOI, DOJ, DOL, ED, EPA, VA

Supporting Organizations: DOT, SBA, Treasury, USDA, VA, ARC, National VOAD

The mission of the Health and Social Services RSF is to help local-led recovery efforts in restoring public health, health care, and social services. The integration of these services promotes community resilience, health, independence, and well-being. (The term “health” subsumes public health, behavioral health, and medical services.) Among the many responsibilities of this RSF is to identify and coordinate with stakeholders an assessment of food, animal, water, and air conditions to ensure safety. Other responsibilities are to coordinate and leverage federal resources for health and social services, and to promote self-sufficiency and continuity of care of affected individuals, especially vulnerable populations. The NDRF envisions specific activities for the Health and Social Services RSF, including encouragement of behavioral health systems to meet the behavioral health needs of affected individuals, response and recovery workers, and the community; the reconnecting of displaced populations with essential health and social services; and the promotion of clear communications and public health messaging to provide accurate and accessible information that is available in multiple mediums, multi-lingual formats, alternative formats and is accessible to underserved populations.

Current limitations of the NDRF A comprehensive analysis of the challenges related to recovery and the utility of the NDRF for addressing them is beyond the scope of this report. Through its information gathering process, however, the committee noted several issues that will ultimately influence the effectiveness of the NDRF as a mechanism for integrating health into the recovery process and thus warrant discussion here.

First, although the NDRF promotes pre-event planning in principle, the framework is not accompanied by any funding to support such planning or capacity building for recovery. The reluctance of federal, state, and local governments to invest in these two critical functions in advance of a disaster has been described as one of the greatest barriers to achieving disaster resilience (Smith, 2011b). As discussed in Chapter 2,

Housing

Coordinating Agency: HUD

Primary Agencies: HUD, DHS/FEMA, DOJ, USDA

Supporting Organizations include HHS

The mission of the housing RSF is to facilitate delivery of federal resources to rehabilitate and reconstruct destroyed or damaged housing and to procure new, accessible permanent housing. This mission can be achieved in part by building accessibility, resilience, sustainability, and mitigation measures into housing recovery in as timely a manner as possible.

Infrastructure Systems

Coordinating Agency: DOD/USACE

Primary Agencies: DOD/USACE, DHS (FEMA and NPPD), DOE, DOT

Supporting Organizations include HHS

The mission of the Infrastructure RSF is to facilitate federal support to local, state, and tribal governments and other infrastructure owners and operators. The scope of this RSF includes energy, water, dams, communications, transportation systems, agriculture, government facilities, utilities, sanitation, engineering, and flood control. This RSF encourages rebuilding infrastructure in a manner that will reduce vulnerability to future disasters.

Natural and Cultural Resources

Coordinating Agency: DOI

Primary Agencies: DOI, DHS/FEMA, EPA

Supporting Organizations do not include HHS

The mission of this RSF is to channel federal assets and capabilities to assist state and local government and communities to address long-term environmental and cultural resource recovery. The key is to protect natural and cultural resources through recovery actions that preserve, conserve, rehabilitate, or restore them. This RSF works to leverage federal resources and available programs to meet local recovery needs.

___________________

NOTES: ARC = American Red Cross; CNCS = Corporation for National and Community Service; CRCL = Civil Rights and Civil Liberties; DHS = U.S. Department of Homeland Security; DOC = U.S. Department of Commerce; DOD = U.S. Department of Defense; DOE = U.S. Department of Energy; DOI = U.S. Department of the Interior; DOJ = U.S. Department of Justice; DOL = U.S. Department of Labor; DOT = U.S. Department of Transportation; ED = U.S. Department of Education; EPA = U.S. Environmental Protection Agency; FEMA = Federal Emergency Management Agency; HHS = U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; HUD = U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development; NPPD = National Protection and Programs Directorate; SBA = U.S. Small Business Administration; USACE = U.S. Army Corps of Engineers; USDA = U.S. Department of Agriculture; VA = U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs; VOAD = Voluntary Organizations Active in Disaster.

SOURCE: FEMA, 2011d.

pre-disaster recovery planning is critical to seizing opportunities for health improvement during recovery. Further, lack of capacity can result in a protracted recovery process and associated negative health effects as community members languish under suboptimal living conditions and experience chronic, toxic stress.

Second, the committee noted incongruence of the NDRF with major federal funding sources that drive community planning at the state and local levels, both during steady-state times and after disasters. During steady state, grants and policies of the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) and the U.S. Department of Transportation (DOT)—now collaborating along with the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) under the banner of the Partnership for Sustainable Communities—are major drivers of urban and regional planning practices. As discussed in Chapter 2, the sustainability practices

NOTES: Although the committee shows here an example in which state and local structures are identical to the federally defined recovery support functions, this need not be the case. Depicted here is a level between state and local—the regional planning level—which should also be considered in alignment with the federal NDRF structure.

CNCS = Corporation for National and Community Service; COG = Council of Governments; CRCL = Civil Rights and Civil Liberties; DHS = U.S. Department of Homeland Security; DOC = U.S. Department of Commerce; DOE = U.S. Department of Energy; DOI = U.S. Department of the Interior; DOJ = U.S. Department of Justice; DOL = U.S. Department of Labor; DOT = U.S. Department of Transportation; ED = U.S. Department of Education; EDD = economic development district; EPA = U.S. Environmental Protection Agency; FEMA = Federal Emergency Management Agency; HHS = U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; HUD = U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development; MPO = metropolitan planning organization; NDRF = National Disaster Recovery Framework; NPPD = National Protection and Programs Directorate; RPC = regional planning commission; RTPO = regional transportation planning organization; SBA = U.S. Small Business Administration; USACE = U.S. Army Corps of Engineers; USDA = U.S. Department of Agriculture; VA = U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs; WIC = Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children.

(e.g., affordable housing, transportation choices) promoted by the Partnership yield significant co-benefits in terms of health outcomes, and the committee sees great benefit to incorporating the Partnership’s livability principles (see Box 2-5 in Chapter 2) into recovery planning, as encouraged by HUD after Hurricane Sandy. Furthermore, HUD-funded community development (e.g., Community Development Block Grant) programs are a major element of community planning and have significant potential to impact the social determinants of health, but they appear to be unlinked to the NDRF structure. Neither HUD nor DOT is included even as a primary agency (both are listed as supporting organizations) for the Community Planning and Capacity Building RSF (FEMA is the coordinating agency).12 This appears inconsistent with the NDRF definition of primary agencies—those having “significant authorities, roles, resources or capabilities for a particular function within an RSF” (FEMA, 2011d, p. 39). Although HUD is the coordinating agency for the Housing RSF, that area of expertise is separate from the agency’s urban planning and community development role. Moreover, after a disaster HUD can have a significant influence on recovery planning at the state and local levels as a funding agency if Congress passes a supplemental appropriation through the HUD Community Development Block Grant for Disaster Recovery (CDBG-DR) vehicle (described in more detail in Chapter 4). After Hurricane Sandy, CDBG-DR funds to support recovery surpassed FEMA disaster relief funds (Donahue, 2014). It is not clear to the committee how CDBG-driven planning is integrated into the NDRF framework. Better incorporation of federal urban planning and community development expertise into the Community Planning and Capacity Building RSF could help address this apparent incongruence.

Finally, testimony provided to the committee revealed that the NDRF, released more than 3 years ago, has not yet been widely adopted and implemented at the state and local levels (Lockwood, 2014; Walsh and Schor, 2014). During a recent study on long-term recovery in which semi-structured interviews were used to collect data on training needs for community leaders in health-related functional roles, the National Center for Disaster Medicine and Public Health found that few respondents who had been actively involved in the recovery from Hurricane Sandy13 were familiar with the NDRF. Those who were familiar felt that its implementation had been problematic because of a lack of guidance, as well as conflicts with existing community recovery plans.14

Current limitations in integration of health into the NDRF The NDRF describes recovery as a continuum of coordinated processes, many concurrent, by which the community

- minimizes and overcomes the physical, emotional, and environmental impacts of a disaster;

- reestablishes an economic and social base that instills confidence in the community members and businesses regarding community viability;

- rebuilds by integrating the functional needs of all residents and reducing the community’s vulnerability to all hazards it faces; and

- demonstrates a capability to be prepared, responsive, and resilient in dealing with the consequences of disasters (FEMA, 2011d, p. 13).

This description clearly conveys the notion that community recovery is not just a “bricks and mortar” process of restoring physical infrastructure; rather, it entails the regeneration of all community systems, functions, and social structures in a way that addresses the full range of needs of the affected community members and ensures that the community has the capacity to meet its future needs. This represents a critical paradigm shift in the nation’s approach to disaster recovery, which has been criticized in the past

________________

13 The NDRF was released approximately 1 year before Hurricane Sandy.

14 Memorandum, K. Schor, Acting Director, National Center for Disaster Medicine and Public Health, to A. Downey, Institute of Medicine, May 28, 2014.

12 The committee did hear that a memorandum of agreement between FEMA and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency is currently used as a mechanism to bring sustainability expertise into the recovery planning process when state and local partners express interest.

for its focus on physical infrastructure and lack of attention to meeting broader human recovery needs such as psychological and social well-being (Chandra and Acosta, 2010). Psychological and emotional recovery is among the core principles laid out in the NDRF, which acknowledges that community recovery is dependent on the recovery of individuals and families (FEMA, 2011d) and that health and social wellbeing are essential to recovery at all levels.

The committee was encouraged to see that Health and Social Services is one of the six RSFs in the NDRF, thus helping to institutionalize the role of health in recovery and to draw attention to the opportunities for improving population health and health systems beyond pre-disaster levels. As indicated in the description of responsibilities for this RSF given in Box 3-3, however, the Health and Social Services RSF is focused narrowly on restoration and delivery of public health, medical, behavioral health, and social services. Although these are unarguably functions critical to protecting and promoting short- and long-term health, they do not capture the full spectrum of factors that affect health within a community or the pathways to health discussed in this and the previous chapter (e.g., collaborations with nonhealth sectors such as urban planning and community development). Since the activities of all sectors will impact health during recovery, either positively or negatively, it is critical that health not be siloed but integrated with all other recovery functions, which should operate cohesively through a systems approach.