8

Health Benefits of Raising the Minimum Age of Legal Access to Tobacco Products

The preceding chapter describes the committee’s conclusions regarding the likely effects of raising the minimum age of legal access to tobacco products (MLA) on initiation of tobacco use by adolescents and young adults under each of the three policy options: MLA 19, MLA 21, or MLA 25. The committee uses SimSmoke and Cancer Intervention and Surveillance Modeling Network (CISNET) simulation modeling to project numerical estimates of how, through to the year 2100, these effects on initiation would affect cigarette smoking prevalence, as the cohorts affected by an MLA increase age into adulthood and, in fact, through middle and older ages. This chapter uses those changes in initiation and prevalence to model the likely effects on morbidity and mortality. Projections from CISNET and SimSmoke include some measures of mortality (premature deaths, years of life lost [YLL], and lung cancer deaths) and of morbidity (low birth weight, pre-term birth, and sudden infant death syndrome, or SIDS). The chapter concludes with the committee’s findings and conclusions on the likely effects of raising the MLA on the many other important health outcomes not included in the modeling exercise. See Appendix D for a detailed discussion of the models.

The CISNET model provided estimates of the smoking-attributable mortality by birth cohort (generation) for each policy option for raising

the minimum age of legal access to tobacco products.1 The mortality predictions by birth cohort summarize in a single statistic the cumulative effects of raising the MLA on the mortality experienced by new generations throughout their lifetime.

Table 8-1 presents the CISNET model projections of lifetime deaths prevented by birth cohort (i.e., for the hypothetical population of U.S. individuals born in 2000–2019, 2020–2039, …, and 2080–2099) for the status quo as well as the premature deaths2 prevented by the mid-scenario of the three MLA policy options for initiation, along with the percentage mortality reduction. The projections show that for each MLA the percentage reduction in premature deaths appears to be consistent across birth cohorts; this makes sense because all the cohorts would reach adulthood after—sometimes substantially after—implementation of the law. Nonetheless, the number of deaths prevented for each birth cohort varies because of differences in the projected size of these different cohorts, with more lives saved in a larger cohort than in a smaller cohort even with the same proportionate reductions. The results show that MLA 19 could reduce the lifetime smoking-attributable deaths versus the status quo by approximately 3 percent, with reductions of 11 percent for MLA 21 and 15 percent for MLA 25. Hence, the projected reductions in smoking-related deaths track the long-run projected declines in smoking prevalence. The results show similar patterns for the upper and lower estimates3 of smoking initiation (see Appendix D).

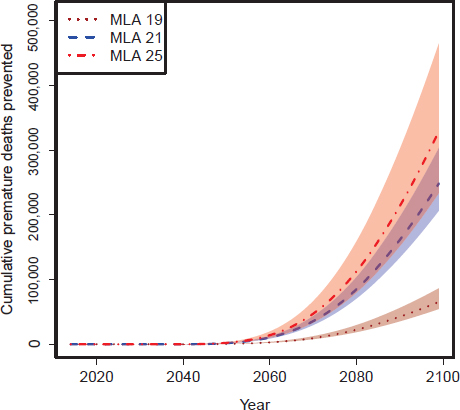

Figure 8-1 shows the CISNET model estimates of the cumulative numbers of premature deaths prevented from 2014 to 2099 for each MLA; these cumulative numbers aggregate over all individuals in the birth cohorts alive during the time period. The lines represent the mid-estimate, and the shaded regions correspond to the upper and lower (see Table 8-2). The figure shows the considerable gains achieved by both MLA 21 and MLA 25

________________

1 Modeling results are presented as cohort effects or period effects. Cohort effects are patterns that differentiate individuals born in the same epoch or generation. Period effects are patterns that characterize individuals who happened to be alive at a certain point in time, independent of their age or generation.

2 Premature deaths are the difference between the effective mortality rate versus the mortality rate of never smokers multiplied by the corresponding age-specific population (see Appendix D).

3 As described in Chapter 7, the simulation models include a range of potential values, resulting in upper and lower estimates around the mid-estimate that vary according to the degree of the committee’s uncertainty, with a broader range for the MLA of 25. The effect ranges do not represent bounds or a measure of uncertainty in the classical statistical sense. Rather, these values reflect ranges that the committee deemed plausible. The mid-estimate is treated as a geometric mean rather than an arithmetic mean; thus, upper estimates are calculated as 1.2(x) and lower estimates as x/1.2 for MLA 19 and MLA 21 and as 1.4(x) and x/1.4 for MLA 25, resulting in slightly nonsymmetric ranges around the mid-estimates.

TABLE 8-1 Lifetime Premature Deaths by Birth Cohort—CISNET Model

| Status Quo | Deaths Averted Under MLA 19 Mid-Scenario | MLA 19 % Reduction | Deaths Averted Under MLA 21 Mid-Scenario | MLA 21 % Reduction | Deaths Averted Under MLA 25 Mid-Scenario | MLA 25 % Reduction | |

| 2000–2019 | 2,160,000 | 59,000 | 2.7% | 223,000 | 10.3% | 296,000 | 13.7% |

| 2020–2039 | 1,996,000 | 58,000 | 2.9% | 218,000 | 10.9% | 289,000 | 14.5% |

| 2040–2059 | 2,024,000 | 58,000 | 2.9% | 222,000 | 10.9% | 293,000 | 14.5% |

| 2060–2079 | 2,097,000 | 60,000 | 2.9% | 229,000 | 10.9% | 304,000 | 14.5% |

| 2080–2099 | 2,171,000 | 63,000 | 2.9% | 238,000 | 10.9% | 315,000 | 14.5% |

NOTE: Although the table carries many significant figures to aid in reproducibility, precision is limited to one or two digits.

FIGURE 8-1 Predicted number of premature deaths prevented (lives saved) for the three MLA policies using the CISNET model. Lines correspond to the mid-scenario for each MLA. Shaded regions represent the area between the upper and lower scenarios for each MLA.

in comparison with MLA 19, with the mortality benefits beginning many years after implementation of the policy, because smoking-attributed mortality becomes more significant after age 40 and the policy primarily affects adolescent and young adult initiation. The figure shows the preservation of the general patterns across the mid, upper, and lower initiation scenarios.

Table 8-2 shows the predicted number of premature deaths due to smoking for selected periods as well as the corresponding number of deaths prevented and the percentage reduction for each of the MLA mid-estimate scenarios. According to the CISNET model, raising the MLA to 19, 21, or 25 would save approximately 66,000, 250,000, or 330,000 lives, respectively, by 2100. Of those lives saved, 23,000 (MLA 19), 90,000 (MLA 21), and 120,000 (MLA 25) would be premature deaths avoided among people

TABLE 8-2 Cumulative Premature Deaths Expected and Prevented by Period—CISNET

| MLA/Outcome |

2020–2039 |

2040–2059 |

2060–2079 |

2080–2099 |

2015–2099 |

| Status Quo | |||||

| Premature deaths expected |

6,782,000 |

4,568,000 |

2,927,000 |

1,996,000 |

18,978,000 |

| MLA 19 | |||||

| Deaths prevented |

— |

3,000 |

20,000 |

43,000 |

66,000 |

| Percentage reduction |

0.0% |

0.1% |

0.7% |

2.2% |

0.0% |

| Deaths prevented (ages <65) |

— |

3,000 |

11,000 |

9,000 |

23,000 |

| MLA 21 | |||||

| Deaths prevented |

— |

11,000 |

75,000 |

163,000 |

249,000 |

| Percentage reduction |

0.0% |

0.2% |

2.6% |

8.2% |

0.3% |

| Deaths prevented (ages <65) |

— |

11,000 |

43,000 |

36,000 |

90,000 |

| MLA 25 | |||||

| Deaths prevented |

— |

14,000 |

99,000 |

216,000 |

329,000 |

| Percentage reduction |

0.0% |

0.3% |

3.4% |

10.8% |

1.3% |

| Deaths prevented (ages <65) |

— |

14,000 |

57,000 |

47,000 |

118,000 |

NOTE: This assumes the use of mid-scenarios and that the policy is implemented in 2015. Although the table carries many significant figures to aid in reproducibility, precision is limited to one or two digits.

younger than 65 years. The table shows that the percentage of premature deaths prevented would increase progressively with time, going from approximately 0.1 percent, 0.2 percent, and 0.3 percent in 2040–2059 to 2.2 percent, 8.2 percent, and 10.8 percent in 2080–2099 for MLA 19, MLA 21, and MLA 25, respectively, all based on the mid-estimate scenarios.

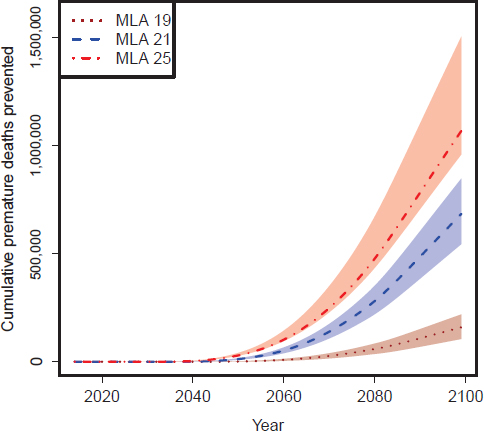

Figure 8-2 shows the SimSmoke model estimates of the number of smoking-related deaths that would be prevented from 2014 to 2100 for each MLA. The model projects more prevented deaths than the CISNET model primarily because of the higher future smoking prevalence predicted by the SimSmoke model and the model differences in assumed mortality rates for current smokers. The CISNET model also allows for differential age-specific mortality by smoking intensity, which is particularly relevant due to the significant decreases in smoking intensity levels projected by the CISNET model under the status quo (see Appendix D).

The relative proportion of deaths prevented between the three MLAs appears consistent across the two models, with MLA 21 and MLA 25 lead-

FIGURE 8-2 Number of premature deaths prevented (lives saved) for the three MLA policies estimated using the SimSmoke model. Lines correspond to the mid-input scenario for each MLA. Shaded regions represent the area between the upper and lower scenarios for each MLA.

ing to significantly greater proportions of lives saved than with MLA 19. In contrast with the SimSmoke model, the CISNET model’s projections of premature deaths prevented for the upper MLA 21 scenario and the lower MLA 25 scenarios overlap, although they still lead to significantly larger gains compared to MLA 19, just as in SimSmoke. Table 8-3 shows the SimSmoke model’s projected number of premature deaths due to smoking for selected periods as well as the corresponding number of deaths prevented and the percentage reduction for each of the MLA mid-scenarios. The table shows that the SimSmoke model estimates that the percentage reduction in smoking-attributed mortality increases progressively with time, from approximately 0.1 percent, 0.8 percent, and 1.5 percent in 2040–2059 to 2.5 percent, 9.9 percent, and 14.5 percent in 2080–2100 for MLA 19, MLA 21, and MLA 25, respectively. Thus, although the absolute numbers

TABLE 8-3 Cumulative Premature Deaths Expected and Prevented by Period—SimSmoke

| MLA/Outcome |

2020–2039 |

2040–2059 |

2060–2079 |

2080–2100 |

2015–2100 |

| Status Quo | |||||

| Premature deaths expected |

8,108,000 |

6,393,000 |

4,963,000 |

4,277,000 |

26,840,000 |

| MLA 19 | |||||

| Deaths prevented |

— |

9,000 |

50,000 |

106,000 |

165,000 |

| Percentage reduction |

0.0% |

0.1% |

1.0% |

2.5% |

0.6% |

| Deaths prevented (ages <65) |

— |

9,000 |

28,000 |

23,000 |

60,000 |

| MLA 21 | |||||

| Deaths prevented |

1,000 |

51,000 |

229,000 |

423,000 |

705,000 |

| Percentage reduction |

0.0% |

0.8% |

4.6% |

9.9% |

2.6% |

| Deaths prevented (ages <65) |

700 |

51,000 |

108,000 |

89,000 |

249,000 |

| MLA 25 | |||||

| Deaths prevented |

4,000 |

99,000 |

375,000 |

620,000 |

1,098,000 |

| Percentage reduction |

0.0% |

1.5% |

8.6% |

14.5% |

4.1% |

| Deaths prevented (ages <65) |

4,000 |

94,000 |

156,000 |

129,000 |

383,000 |

NOTE: Assumes the use of mid-scenarios and that the policy is implemented in 2015. Although the table carries many significant figures to aid in reproducibility, precision is limited to one or two digits.

of deaths prevented differ considerably between the models, the percentage reductions in smoking-attributable deaths appear relatively consistent, especially for later years.

Tables 8-4 and 8-5 show estimates of the number of YLL in the United States for each of the MLA scenarios by calendar-year (period) and birth cohort, respectively. The calendar-year results (see Table 8-4) suggest the gains in years of life would begin several decades after implementation of the policy. Nonetheless, the birth cohort results (see Table 8-5) show large reductions in the lifetime YLL (>10 percent) achieved by MLA 21 or MLA 25 for new generations, starting with those born in 2000–2019, with similar patterns observed for the upper and lower smoking initiation input values (see Appendix D).

Finding 8-1: Model results suggest that reductions in smoking-related mortality will not be observed for at least 30 years following the increase in the minimum age of legal access to tobacco products.

TABLE 8-4 Years of Life Lost (YLL) by Period—CISNET Model

| Status Quo | YLL Under MLA 19 Mid-Scenario | MLA 19 % Reduction | YLL Under MLA 21 Mid-Scenario | MLA 21 % Reduction | YLL Under MLA 25 Mid-Scenario | MLA 25 % Reduction | |

| 2000–2019 | 134,823,000 | — | 0.0% | — | 0.0% | — | 0.0% |

| 2020–2039 | 106,126,000 | — | 0.0% | — | 0.0% | — | 0.0% |

| 2040–2059 | 68,217,000 | 100,000 | 0.1% | 352,000 | 0.5% | 469,000 | 0.7% |

| 2060–2079 | 46,490,000 | 561,000 | 1.2% | 1,979,000 | 4.3% | 2,641,000 | 5.7% |

| 2080–2099 | 36,688,000 | 964,000 | 2.6% | 3,401,000 | 9.3% | 4,542,000 | 12.4% |

NOTE: Although the table carries many significant figures to aid in reproducibility, precision is limited to one or two digits.

TABLE 8-5 Lifetime Years of Life Lost (YLL) by Cohort—CISNET Model

| Status Quo | YLL Under MLA 19 Mid-Scenario | MLA 19 % Reduction | YLL Under MLA 21 Mid-Scenario | MLA 21 % Reduction | YLL Under MLA 25 Mid-Scenario | MLA 25 % Reduction | |

| 2000–2019 | 40,116,000 | 1,180,000 | 2.9% | 4,163,000 | 10.4% | 5,560,000 | 13.9% |

| 2020–2039 | 36,447,000 | 1,134,000 | 3.1% | 4,000,000 | 11.0% | 5,343,000 | 14.7% |

| 2040–2059 | 36,084,000 | 1,123,000 | 3.1% | 3,962,000 | 11.0% | 5,291,000 | 14.7% |

| 2060–2079 | 37,412,000 | 1,164,000 | 3.1% | 4,108,000 | 11.0% | 5,486,000 | 14.7% |

| 2080–2099 | 38 874 000 | 1 210 000 | 3 1% | 4 268 000 | 11 0% | 5 700 000 | 14 7% |

NOTE: Although the table carries many significant figures to aid in reproducibility, precision is limited to one or two digits.

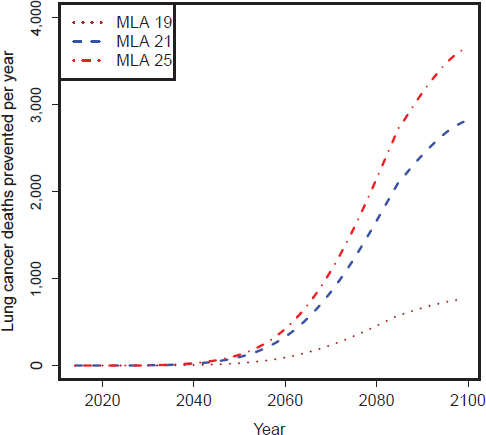

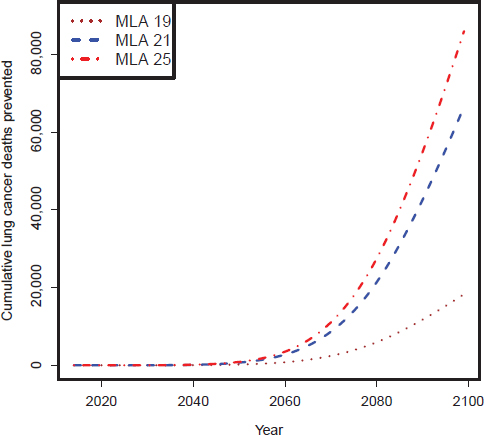

The CISNET Yale Lung Cancer Model, in combination with the CISNET smoking population model, provides estimates of lung cancer deaths prevented (Holford et al., 2012; Moolgavkar et al., 2012). The model uses a multistage lung carcinogenesis model to translate the population patterns of smoking projected by the CISNET smoking population model into predictions of lung cancer deaths (Hazelton et al., 2012; Meza et al., 2008). More details are provided in Appendix D. Figure 8-3 shows the projected number of annual lung cancer deaths prevented for each of the MLA mid-scenarios. Figure 8-4 shows the corresponding cumulative number of lung cancer deaths prevented. The figures show that the reductions in lung cancer mortality would not become observable until the late 2040s because of the time delay between smoking exposure and lung cancer risk. As in the case with

FIGURE 8-3 CISNET model estimates of the number of lung cancer deaths prevented per year for the three MLAs (mid-scenario).

FIGURE 8-4 CISNET model estimates of the number of cumulative lung cancer deaths prevented per year for the three MLAs (mid-scenario).

overall mortality, the model predicts that raising the MLA to 21 or 25 would lead to a considerably higher number of lung cancer deaths prevented than if the MLA was raised only to 19. Table 8-6 shows the projected number of lung cancer deaths and deaths prevented for selected periods for each MLA (mid-scenario). The table shows the progressive increase in the percentage of lung cancer deaths prevented, going from 0.1 percent, 0.3 percent, and 0.4 percent in 2040–2059 to 2.9 percent, 10.5 percent, and 13.6 percent in 2080–2099 for MLA 19, MLA 21, and MLA 25, respectively.

Finding 8-2: Raising the minimum age of legal access to tobacco products to 21 or 25 years would lead to larger reductions in smoking-attributable mortality than keeping the status quo or raising the MLA to 19 years.

TABLE 8-6 Lung Cancer Deaths and Prevented Deaths by Period Under Each MLA (CISNET)

|

2020–2039 |

2040–2059 |

2060–2079 |

2080–2099 |

|

| Status Quo |

1,388,000 |

771,000 |

510,000 |

431,000 |

| MLA 19 |

0 |

1,000 |

5,000 |

12,000 |

| averted percentage reduction |

0.0% |

0.1% |

1.0% |

2.8% |

| MLA 21 |

0 |

3,000 |

19,000 |

45,000 |

| averted percentage reduction |

0.0% |

0.4% |

3.7% |

10.4% |

| MLA 25 |

0 |

3,000 |

24,000 |

59,000 |

| averted percentage reduction |

0.0% |

0.4% |

4.7% |

13.7% |

NOTE: Although the table carries many significant figures to aid in reproducibility, precision is limited to one or two digits.

Finding 8-3: Modeling mortality outcomes by birth cohort estimates that large reductions in lifetime smoking-attributable deaths and years of life lost would be achieved by raising the minimum age of legal access to tobacco products to age 21 or 25 for new generations starting with the cohort born in 2000. It also projects the prevention of a large number of lung cancer deaths under such scenarios, with most of these prevented deaths realized after 2050.

MATERNAL AND CHILD HEALTH OUTCOMES

The fetal and early infancy periods in life are particularly critical periods for future development, and, as such, adverse exposures are especially harmful during these periods (HHS, 2004). Cigarette smoke exposure has potent adverse effects that negatively affect the likelihood of conception, degrade the health of pregnant women and the developing fetus, increase the risk of pregnancy complications, and reduce the likelihood of infant survival (HHS, 2004). An increase in the MLA would therefore have a robust and immediate impact in improving maternal/fetal and infant outcomes by reducing the likelihood of maternal/paternal smoking. Benefits would be expected to occur immediately with a change in the MLA, and they would at first be concentrated within the younger ages of the reproductive years because of the short-term policy impact that would quickly appear by reducing smoking prevalence in this age range. The impact of a raise in the MLA would then increase over time as the early birth cohorts affected by the MLA increase aged into the reproductive ages. The magnitude of the benefit would be directly associated with the magnitude of the decrease in smoking prevalence.

The SimSmoke model projected the effects of raising the MLA on the incidence of pre-term births (PTBs), low birth weight (LBW), and SIDS. The focus on maternal health outcomes required modification of the model to distinguish the number of smoking women who become pregnant and the number of children born to smoking women. The model calculated the number of cases of smoking-attributable birth outcomes using standard attribution formulas based on relative risks and projected smoking prevalence (HHS, 2010; Levin, 1953; Lilienfeld and Lilienfeld, 1980) (see Appendix D).

Tables 8-7, 8-8, and 8-9 show the predicted cumulative numbers of LBW, PTB, and SIDS, respectively, for each MLA for the mid-scenario and the corresponding number of averted cases versus the status quo for selected years. For mothers ages 15 to 49, the SimSmoke model predicts that about 124,000 LBW cases, 82,000 PTBs, and 1,100 SIDS deaths would be averted between 2015 and 2100 for MLA 19. These increase to 438,000 LBW cases, 286,000 PTBs, and 4,000 SIDS deaths averted under MLA 21 and to 597,000 LBW cases, 388,000 PTBs, and 5,400 SIDS deaths averted under MLA 25. Thus, about three times more cases could be avoided under MLA 21 than under MLA 19, while only about 1.35 times more cases could be prevented under MLA 25 than under MLA 21.

TABLE 8-7 Smoking Attributable LBW Cases and Averted Cases by Period Under Each Policy Option (Mothers Ages 15–49) (SimSmoke)

|

2015–2019 |

2020–2039 |

2040–2059 |

2060–2079 |

2080–2099 |

|

| Status Quo |

242,000 |

727,000 |

854,000 |

964,000 |

1,064,000 |

| MLA 19 |

2,000 |

22,000 |

30,000 |

34,000 |

37,000 |

| averted percentage reduction |

0.8% |

3.0% |

3.5% |

3.5% |

3.5% |

| MLA 21 |

10,000 |

78,000 |

104,000 |

117,000 |

129,000 |

| averted percentage reduction |

4.1% |

10.7% |

12.2% |

12.1% |

12.1% |

| MLA 25 |

16,000 |

109,000 |

140,000 |

158,000 |

174,000 |

| averted percentage reduction |

6.6% |

15.0% |

16.4% |

16.4% |

16.4% |

NOTE: Although the table carries many significant figures to aid in reproducibility, precision is limited to one or two digits.

TABLE 8-8 Smoking Attributable PTB Cases and Averted Cases by Period Under Each Policy Option (Mothers Ages 15–49) (SimSmoke)

|

2015–2019 |

2020–2049 |

2040–2059 |

2060–2079 |

2080–2099 |

|

| Status Quo |

148,000 |

442,000 |

520,000 |

587,000 |

648,000 |

| MLA 19 |

1,000 |

14,000 |

20,000 |

22,000 |

24,000 |

| averted percentage reduction |

0.9% |

3.2% |

3.8% |

3.8% |

3.8% |

| MLA 21 |

6,000 |

51,000 |

68,000 |

76,000 |

84,000 |

| averted percentage reduction |

4.3% |

11.6% |

13.0% |

13.0% |

13.0% |

| MLA 25 |

11,000 |

71,000 |

91,000 |

103,000 |

113,000 |

| averted percentage reduction |

8.2% |

16.0% |

18.5% |

18.5% |

18.5% |

NOTE: Although the table carries many significant figures to aid in reproducibility, precision is limited to one or two digits.

TABLE 8-9 Smoking Attributable SIDS Cases and Averted Cases by Period Under Each Policy Option (Mothers Ages 15–49) (SimSmoke)

|

2015–2019 |

2020–2049 |

2040–2059 |

2060–2079 |

2080–2099 |

|

| Status Quo |

2,280 |

6,850 |

8,060 |

9,090 |

10,020 |

| MLA 19 |

20 |

200 |

270 |

300 |

340 |

| averted percentage reduction |

0.8% |

3.0% |

3.4% |

3.4% |

3.4% |

| MLA 21 |

100 |

730 |

950 |

1,070 |

1,180 |

| averted percentage reduction |

4.2% |

10.7% |

11.7% |

11.7% |

11.7% |

| MLA 25 |

160 |

1,010 |

1,270 |

1,430 |

1,580 |

| averted percentage reduction |

8.0% |

14.7% |

15.8% |

15.7% |

15.7% |

NOTE: Although the table carries many significant figures to aid in reproducibility, precision is limited to one or two digits.

Finding 8-4: Modeling estimates that immediate reductions in cases of low birth weight, pre-term birth, and sudden infant death syndrome will occur with changes in the minimum age of legal access to tobacco products.

TABLE 8-10 Reduction (percentage) in Smoking Prevalence for MLA 21 by Year

| 2020 | 2040 | 2060 | 2080 | 2100 | |

| Smoking prevalence—SimSmoke | 2.0% | 8.3% | 10.3% | 11.2% | 11.20% |

| Smoking prevalence—CISNET | 0.4% | 6.4% | 10.6% | 11.9% | 12.00% |

TABLE 8-11 Reduction (percentage) in Health Outcomes for MLA 21 by Period

|

2020–2039 |

2040–2059 |

2060–2079 |

2080–2099 |

|

| Deaths prevented—SimSmoke |

0.0% |

0.8% |

4.6% |

9.9% |

| Deaths prevented—CISNET |

0.0% |

0.2% |

2.6% |

8.2% |

| Years of life lost—CISNET |

0.0% |

0.5% |

4.3% |

9.3% |

| Lung cancer deaths prevented |

0.0% |

0.3% |

3.7% |

10.5% |

| Low birth weight cases |

10.8% |

12.2% |

12.2% |

12.2% |

| Pre-term birth cases |

11.6% |

13.0% |

13.0% |

13.0% |

| Sudden infant death syndrome cases |

16.0% |

18.5% |

18.5% |

18.5% |

Tables 8-10 and 8-11 summarize the reductions in smoking prevalence for selected years and health outcomes by 20-year periods for MLA 21, showing the relative timing at which different benefits occur. The results illustrate the longer times required for chronic outcomes compared to short-term outcomes.

The previous section laid out the results of the simulation modeling regarding the likely effects of raising the MLA on cigarette-related mortality and select health outcomes, limited to the capacity of the commissioned models. However, such results can only begin to estimate the magnitude of the effects of reduced tobacco use on individual and population health in the United States. As the cohorts of adolescents and young adults affected by a raise in the MLA age, the benefits accrue and grow over time. The adverse health effects of tobacco use are well documented and described in Chapter 4. Here, the committee describes qualitatively the wide spectrum of likely benefits to health throughout the life span from decreased tobacco

initiation in adolescents and young adults and the resulting lowered prevalence rates in adulthood. It should be stressed that most of the data about adverse health effects of tobacco come from studies of cigarette smoking.

Cigarette smoking causes the immediate adverse health effects of increased oxidative stress; depletion of selected bioavailable antioxidant micronutrients; increased inflammation; impaired immune status; altered lipid profiles; poorer self-rated health status; respiratory symptoms such as coughing, phlegm, wheezing, and dyspnea; and nicotine addiction (HHS, 2004). As summarized above, increasing the MLA would be expected to reduce the initiation of tobacco use by adolescents and young adults, which would naturally lead to a decrease in the prevalence of tobacco use. Reducing the prevalence of smoking by any amount will automatically lead to immediate population health benefits that are directly proportional to the size of the reduction. Each one of the immediate adverse health effects caused by cigarette smoking itself compromises the health status of smokers, and when combined, this constellation of immediate adverse health effects leaves the smoker with a health status that is significantly impaired and subpar compared to nonsmokers. For example, smokers are less able to fend off acute infectious diseases and more likely to exhibit respiratory symptoms (HHS, 2014). The cumulative toll leaves the smoker generally feeling worse off about his or her health status soon after starting to smoke (HHS, 2004, 2014). Nicotine addiction makes the smoker more likely to keep smoking over the long term, which in turn makes the smoker more and more prone to the immediate and long-term health effects as the lifetime extent of smoking grows.

The immediate adverse health effects of smoking affect people of all ages, but the immediate impact upon adolescents who initiate smoking is the most disconcerting from a population health perspective because these adverse consequences occur during such a critical developmental period of life. The immediate health effects result in adolescents and young adults who smoke having compromised educational achievement, diminished athletic performance, reduced proficiency in performing occupational duties, and, for those enlisted in the armed forces, having compromised military performance (HHS, 2004). In fact, each of these populations of students, workers, and military personnel can be viewed as having a subpopulation of smokers that is physiologically disadvantaged compared to the nonsmoker portion of the population. Thus, a reduction in smoking prevalence by any amount is a step toward reducing a population health disparity that is created by cigarette smoking even in the ostensibly healthy population of adolescents and young adults. The larger the reduction in

smoking prevalence created by raising the MLA, the larger the commensurate reduction will be in these smoking-caused health disparities. Reducing the prevalence of these immediate adverse health effects would not only benefit population health but also have downstream benefits on population educational achievement, workforce productivity, and military performance. The higher the MLA, the greater the public health benefit will be in terms of reducing the size of the population of smokers and hence decreasing the number who experience the corresponding health deficits.

Further public health benefits will occur from the delays in the age of starting to smoke that would result from raising the MLA for tobacco. Within the age range where the delays occur, the delayed age of initiation would postpone the immediate adverse health effects until the individuals are older. The child and adolescent population would directly benefit, with a smaller percentage of the adolescent population smoking and a larger percentage maintaining a more optimal health status. Delaying smoking in adolescents until they are older would help protect the tissues and organ systems that are still in the growth and maturation phase during adolescence and hence are particularly vulnerable to the detrimental effects of the toxicants in smoke (HHS, 2004). As with the prevention of smoking, the extent to which smoking initiation will be delayed will be directly related to how high the MLA is set.

Cigarette smoking causes the intermediate adverse health effects of increased absence from school and work, increased use of medical services, subclinical atherosclerosis, impaired lung development and function, increased risk of lung infections, diabetes, periodontitis, exacerbation of asthma, subclinical organ injury, and adverse surgical outcomes (HHS, 2004). The reductions in smoking prevalence caused by increasing the MLA will reduce the entire burden that these intermediate adverse health effects pose to population health. The estimated amount of reduction in this burden will be larger with a higher MLA and will grow in magnitude over time as the policy impact matures.

Reducing the prevalence of smoking will lead to population health benefits in the near term by reducing the burden of the intermediate adverse health effects of cigarette smoking. Each of the intermediate adverse health effects caused by cigarette smoking compromises an individual smoker’s health status; in total, they combine to exact a severe toll on individuals and on population health in general. They further widen the health status differential between smokers and nonsmokers, which commences with the immediate adverse health effects. The intermediate health effects leave the smoker not only with subclinical diminished health status but also with

clinically apparent morbidities across multiple organ systems (HHS, 2004). In turn, the diminished health status and clinical morbidities have a detrimental influence on the national economy both by limiting workforce productivity via absences and also by increasing health care costs (HHS, 2004). The morbidities experienced by smokers during this intermediate period are outward manifestations of the subclinical effects that begin immediately after smoking initiation, a fact that reinforces the observation that the health status of smokers is diminished throughout the life span compared to nonsmokers, even before the impact of clinically apparent morbidities and then mortality make this difference in health status obvious.

These intermediate adverse health effects affect the entire age continuum, generating clear smoker–nonsmoker health disparities during early life (HHS, 2004, 2014). As with the immediate health effects, as smoking persists into adulthood the divergence in markers of health status between smokers and nonsmokers widens. Cigarette smokers constitute a sub-population that is physiologically disadvantaged compared with the nonsmoker population, and a reduction in smoking prevalence resulting from an increase in the MLA is a step toward achieving a reduction in smoking-caused population health disparities.

The public health benefits from delayed initiation would not simply be seen in a decrease in the immediate adverse health effects, but would continue to have a ripple effect over time, benefiting people at all ages and stages of life. For example, the fact that delayed initiation reduces the dose of cigarette toxins ingested by smokers would help to offset the population burden of intermediate health effects, and because an older age of initiation is associated with increased likelihood of cessation, this would further benefit population health by leading to further reductions in cigarette smoking prevalence during those stages of life affected by the intermediate adverse health effects of cigarette smoking.

Cigarette smoking is causally associated with a long list of long-term health effects that includes 12 different types of cancer, vascular and heart disease outcomes, respiratory disease, eye disease, rheumatoid arthritis, and bone health (HHS, 2004, 2014). The immediate, intermediate, and long-term adverse health effects of cigarette smoking are related as several of these long-term outcomes are mechanistically linked to the immediate and intermediate adverse health effects summarized above. Cancer, cardiovascular disease, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease are caused by smoking and are also the major causes of death in the United States (HHS, 2014); thus, these specific outcomes are also included indirectly in the statistical modeling of all-cause mortality. On the other hand, although such

long-term adverse health effects as eye disease, rheumatoid arthritis, and adverse effects on bone health are not direct causes of death, they do pose a major burden of disability and impaired quality of life in the U.S. population (HHS, 2004, 2014). Furthermore, regardless of the ultimate prognosis, cancer, cardiovascular disease, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease all contribute to the burden of disability and impaired quality of life.

Unlike the case with the immediate and intermediate adverse health effects caused by cigarette smoking, the impact of increasing the MLA on long-term adverse health effects caused by cigarette smoking would not become apparent until decades after the policy change occurred because raising the MLA will primarily affect the initiation and delay of smoking among children, adolescents, and young adults. Therefore, the impact of raising the MLA on the long-term adverse health effects would not occur until the initial birth cohorts affected by an MLA increase were old enough to be in the older age groups where these chronic diseases typically occur. The degree of morbidity reduction in these cohorts would be expected to be directly correlated with the decrease in smoking prevalence and delayed initiation that the older MLA generated. The population health impact would be profound even for modest decreases in smoking prevalence because of the broad spectrum of the long-term health effects caused by smoking and the population health burden caused by each of these diseases. Delays in initiating cigarette smoking would result in further reductions in the long-term adverse health effects caused by smoking because of reductions in the population-level exposure to tobacco toxins; these reductions would occur because a later age of initiation leads to individuals smoking fewer cigarettes per day, on average, and also for fewer years because individuals who start smoking later are more likely to eventually quit.

The focus here has been specifically on the public health effects of reducing the prevalence of, and delaying initiation of, cigarette smoking. Raising the MLA will also reduce the prevalence of smoking combustible tobacco products other than cigarettes, such as pipes and cigars. As reviewed in Chapter 4, although less thoroughly studied than cigarette smoking, smoking other tobacco products also causes significant adverse health effects that will be prevented with a reduction in prevalence. Furthermore, raising the MLA will lead to reductions in smokeless tobacco use and hence a reduction in the adverse health effects caused by smokeless tobacco use.

By reducing the prevalence of smoking of all tobacco products in the population, raising the MLA will also lead to a reduction in the population exposure to secondhand smoke (SHS). A reduction in the prevalence of exposure to SHS will benefit public health by reducing the spectrum of adverse health effects, reviewed in Chapter 4, that have been causally associated with SHS exposure.

IMPLICATIONS OF RAISING THE MINIMUM AGE OF LEGAL ACCESS TO TOBACCO PRODUCTS ON HEALTH

The modeling analysis suggests that raising the MLA could lead to considerable reductions in smoking-attributed mortality and morbidity over time, mirroring the reductions in smoking discussed earlier. Both models suggest a time delay of a few decades for the overall mortality benefits to accrue at the population level because of the lag time between smoking exposure and major health outcomes and because the policy primarily affects adolescents and young adults. Nonetheless, more immediate effects would be observed for maternal and child outcomes as well as other acute outcomes. Moreover, the analysis shows that new generations, starting with those born between 2000 and 2019, could see significant reductions in mortality and years of life lost accumulated throughout their lifetimes.

Both models suggest that significant mortality gains occur when going from MLA 19 to MLA 21. Increasing the MLA from 21 to 25 leads to additional benefits, but the magnitude of these benefits is less than achieved when going from MLA 19 to MLA 21, based on conservative assumptions that reflect uncertainty about extrapolation to MLA 25.

The CISNET model predicts about one-third as many premature deaths prevented as the SimSmoke model. This occurs largely because of the lower smoking prevalence projected by the CISNET model for all cases and the concomitant lower baseline smoking-attributable deaths. Furthermore, the CISNET model allows for differential mortality by smoking intensity. Thus, the large reductions in smoking intensity levels projected by this model translate into fewer estimated smoking-attributable mortality in all cases than in the SimSmoke model. Nonetheless, the estimated percentage mortality reductions of the different MLAs appear consistent between the two models, particularly for later years.

Raising the MLA would significantly reduce lung cancer mortality in the long term, with most of the benefits realized after 2050. Similarly, as with the overall mortality projections, the models predict considerably larger reductions when raising the MLA to 21 or 25 versus 19. Raising the MLA to 19, 21, and 25 will reduce LBW, PTB, and SIDS outcomes, with these benefits occurring relatively earlier in time.

All models come with limitations because their results depend on the model structure and assumptions. In this case, uncertainty also arises from the assumptions about the effects of various MLA policies on smoking initiation scenarios. The committee used an evidence-driven process to create the inputs regarding potential ranges for the assumed effects of the MLA policies. While these inputs are assumptions, they are well reasoned based on the existing evidence regarding adolescent and young adult smoking behavior and tobacco control policy responses, as explained in Chapter 7.

The use of two established tobacco control simulation models with differences in the underlying assumptions related to future baseline initiation and cessation rates led to different estimates of the absolute decrease in smoking prevalence and different status quo estimates. However, the two distinct models predict similar results for the percentage reductions associated with the various MLA options considered. Similarly, although the models differ in their predicted absolute numbers of deaths prevented, they agree in their estimated relative reductions and relative effects among the different MLAs. This provides some confidence about these overall findings. Sensitivity analyses (see Appendix D) showed that the conclusions about the relative effects of the different MLAs appear robust to alternative assumptions on the initiation effects (upper and lower scenarios).

The projections provide somewhat conservative estimates, given that the models did not account for the possible synergistic effects of reduced and delayed initiation with increased cessation, and the committee estimates accounted for greater uncertainty about projection to an MLA 25 policy. Moreover, the models only considered smoking, ignoring the potential additional health benefits from reductions in the consumption of other tobacco products. The models also ignored the potential additional health benefits from reductions in the consumption of other tobacco products and the likely synergistic effects of increased cessation on disease risk. The models also ignore benefits that might accrue because nonsmokers engage in a variety of healthy behaviors compared to smokers. Overall, the results from both models are consistent with the conclusions from the literature review and show that raising the MLA would lead to significant health benefits. Some, such as maternal and child health outcomes, will occur immediately, while others, such as overall mortality benefits, will take time to accrue.

Conclusion 8-1: Based on the modeling, raising the minimum age of legal access to tobacco products will likely lead to substantial reductions in smoking-related mortality.

As described above and in Chapter 4, cigarette smoking causes numerous adverse health effects, and these can be categorized as immediate, intermediate, or long term. In assessing the potential public health impact of raising the MLA, it is worth keeping in mind that this lengthy catalogue of well-established consequences of cigarette smoking and SHS exposure will grow as more definitive evidence coalesces for additional health outcomes. There are many additional adverse health effects currently suspected of being causally associated with both cigarette smoking and SHS exposure,

but the evidence currently falls short of being definitive; thus, the scope of adverse health effects will grow over time.

Considering the causes of the health effects of cigarette smoking throughout the entire life course more accurately characterizes the full extent of the public health burden imposed by cigarette smoking. It is important to emphasize that because the spectrum of adverse health effects caused by cigarette smoking is so extensive in both the near term and the long term, even small reductions in smoking prevalence will benefit public health substantially. The magnitude of the public health impact will be larger for greater reductions in smoking prevalence; thus, the public health impact will be greatest for an MLA of 25 years and least for an MLA of 19 years.

Conclusion 8-2: Based on a review of the literature, raising the minimum age of legal access to tobacco products (MLA) will likely immediately improve the health of adolescents and young adults by reducing the number of those with smoking-caused diminished health status. As the initial birth cohorts affected by the policy change age into adulthood, the benefits of the reductions of the intermediate and long-term adverse health effects will also begin to manifest. Raising the MLA will also likely reduce the prevalence of other tobacco products and exposure to secondhand smoke, further reducing tobacco-caused adverse health effects, both immediately and over time.

Conclusion 8-3: Based on a review of the literature and on the modeling, an increase in the minimum age of legal access to tobacco products will likely improve maternal, fetal, and infant outcomes by reducing the likelihood of maternal and paternal smoking.

As discussed in Chapter 7 with regard to effects of an increase in the MLA on tobacco initiation, it is an open question whether raising the MLA will have a greater or lesser impact on the health of population subgroups with a higher prevalence of cigarette smoking than on the general population. If the reduction in smoking prevalence was proportionally larger in the subgroups of the population with the highest smoking prevalence, then the public health impact of raising the MLA might be even greater than anticipated. If the converse were true, however, and these population subgroups were more resistant to the influence of the policy with respect to reducing smoking prevalence and delayed initiation, then the end result would be to widen the existing disparities.

Hazelton, W. D., J. Jeon, R. Meza, and S. H. Moolgavkar. 2012. Chapter 8: The FHCRC lung cancer model. Risk Analysis 32(Suppl 1):S99–S116.

HHS (Department of Health and Human Services). 2004. The health consequences of smoking: A report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health.

———. 2010. Smoking-attributable mortality, morbidity, and economic costs (SAMMEC). https://apps.nccd.cdc.gov/sammec/mch_mort_comp.asp?cdc=706 (accessed January 29, 2015).

———. 2014. The health consequences of smoking—50 years of progress: A report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health.

Holford, T. R., K. Ebisu, L. McKay, C. Oh, and T. Zheng. 2012. Chapter 12: Yale Lung Cancer Model. Risk Analysis 32(Suppl 1):S151–S165.

Levin, M. 1953. The occurrence of lung cancer in man. Acta Unio Internationalis Contra Cancrum 9:531–541.

Lilienfeld, A., and D. Lilienfeld. 1980. Foundations of epidemiology. New York: Oxford University Press.

Meza, R., W. D. Hazelton, G. A. Colditz, and S. H. Moolgavkar. 2008. Analysis of lung cancer incidence in the Nurses’ Health and the Health Professionals’ Follow-Up Studies using a multistage carcinogenesis model. Cancer Causes and Control 19(3):317–328.

Moolgavkar, S. H., T. R. Holford, D. T. Levy, C. Y. Kong, M. Foy, L. Clarke, J. Jeon, W. D. Hazelton, R. Meza, F. Schultz, W. McCarthy, R. Boer, O. Gorlova, G. S. Gazelle, M. Kimmel, P. M. McMahon, H. J. de Koning, and E. J. Feuer. 2012. Impact of reduced tobacco smoking on lung cancer mortality in the United States during 1975–2000. Journal of the National Cancer Institute 104(7):541–548.