3

Why Should Businesses Engage in Population Health Improvement?

A recurring theme across prior roundtable discussions has been that population health improvement requires multi-sector and multi-stakeholder engagement, said session moderator Andrew Webber, chief executive officer of the Maine Health Management Coalition. This workshop was focused on one particular stakeholder group—the business community—and speakers in this session discussed a variety of reasons business might or should engage in population health improvement. Michael O’Donnell, director of the Health Management Research Center at the University of Michigan, discussed the relationship of health to the federal debt and the creation of jobs. Catherine Baase, chief health officer at The Dow Chemical Company, used a macroeconomic model to illustrate how the current health scenario is negatively affecting the success of the business sector. Nicolaas Pronk, vice president and chief science officer at HealthPartners, described an initiative to develop the underlying rationale and business case for companies to invest in community and population health.

Webber reminded participants that there is not one homogeneous “business community,” although all businesses are focused on remaining competitive in their market, and there is often a shared culture that informs how businesses determine whether there is a clear business strategy for engaging in an issue like population health and health care. Webber noted that although there has been a significant increase in worksite health promotion and wellness programs, engaging business at the broader community level has been more of a challenge (Webber and Mercure, 2010).

CREATING JOBS AND REDUCING FEDERAL DEBT THROUGH IMPROVED HEALTH

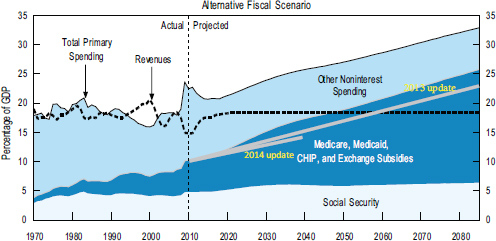

O’Donnell posed the question of whether improving population health could lead to reduced federal debt and to the creation of jobs. As background, he noted that in 1970 federal spending on health care (e.g., Medicare, Medicaid, Children’s Medicaid, and exchange subsidies) was about 1 percent of the country’s gross domestic product (GDP), and spending on Social Security was about 4 percent of GDP. In 2011 long-term budget scenarios from the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) suggested that federal spending on health care could reach 19 percent of GDP by 2085, with spending on social security projected to increase to about 6 percent of GDP (see Figure 3-1). Updated CBO projections in 2013 suggested that federal spending on health care might only reach 14 percent of GDP, and a recent short-term projection suggests further reductions in predicted federal health care spending (CBO, 2011, 2013, 2014).

The current annual budget deficit is not the problem, O’Donnell said. Rather, it is the long-term federal debt.1 If current CBO long-term budget scenarios hold true, by 2035 the U.S. federal debt could be 200 percent of GDP, O’Donnell said (compared with the current federal debt of about 75 percent of GDP). He suggested that such a situation would be a fiscal crisis beyond compare for the United States.

The Health-Related Contributors to the Federal Debt

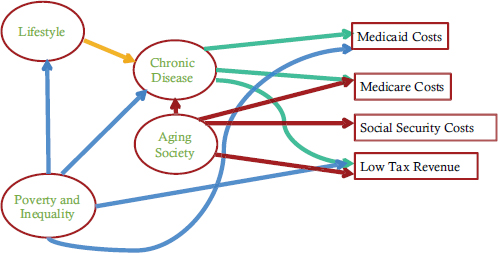

O’Donnell listed four underlying health-related causes of federal debt: lifestyle, chronic disease, an aging society, and poverty and inequality (see Figure 3-2). For example, lifestyle can lead to increased chronic disease, resulting in increased Medicare or Medicaid costs for covered individuals and also in reduced tax revenues from these individuals because they cannot work. Poverty and inequality have a negative impact on lifestyle and health, and they are associated with increased Medicaid costs and decreased tax revenues.

Opportunities Presented by Improved Health

Based on his own calculations, O’Donnell suggested that improving the health of the population can reduce the federal debt in various ways:

________________

1 The annual shortfall between spending and receipts is the deficit. Borrowing to meet each year’s deficit adds to the federal debt.

FIGURE 3-1 Primary spending and revenues, by category, under CBO’s long-term budget scenarios through 2085.

NOTES: CHIP = Children’s Health Insurance Program; GDP = gross domestic product.

SOURCE: CBO, 2011.

FIGURE 3-2 Underlying health-related causes of federal debt.

SOURCE: O’Donnell, 2012. Used with permission.

- Expanding the average years of working life by 5 months would reduce the federal debt by 1.6 percent.

- Expanding the average years of working life by 4.5 years would reduce federal debt by 16 percent.

- Expanding the average years of working life by 9 years would reduce federal debt by 32 percent.

- Reducing the annual rate of increase of Medicare by 0.1 percent would reduce the federal debt by 1.5 percent.

- Reducing the annual rate of increase of Medicare by 1 percent would reduce the federal debt by 15 percent.

- Reducing the annual rate of increase of Medicare by 2 percent would reduce the federal debt by 30 percent.

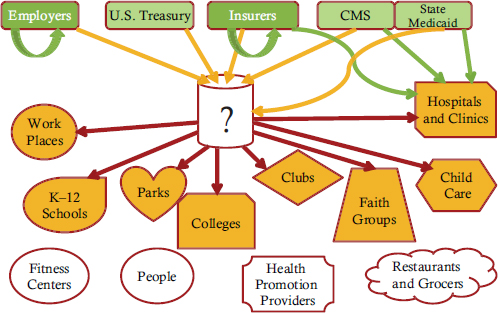

Improved health will, of course, also improve the well-being and quality of life of millions of people, he added. To facilitate these health improvements, O’Donnell recommended that funding come from organizations that can benefit from the improved health of the population, including employers and insurers, the U.S. Treasury (through the taxes it collects from employers), the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, and state Medicaid programs, and then flow to organizations that can engage people in effective health-improvement programs where they live, work, learn, play, and pray (see Figure 3-3).

A budget of $200 per person per year would provide approximately $62 billion per year, O’Donnell said (assuming 310 million2 people). According to O’Donnell, this is about five times the current public health department spending per person (about $41 in 2005), about 30 times the spending of the existing workplace health promotion industry, about 2 percent of spending on medical care in the United States, and 0.32 percent of the liquid assets that non-farm, non-financial institutions have in the bank. This is definitely within our spending ability, O’Donnell asserted, and short-term costs may actually be covered by the short-term savings (in addition to reducing the federal debt in the long term).

In addition to reducing debt, O’Donnell said that growing the workplace health promotion field from $2 billion to $60 billion would create about 280,000 new health promotion jobs at about $75,000 per job (including benefits). He said that this would stimulate $4 billion in new state income taxes and about $22 billion in new federal income taxes. These funds would be sufficient to fund health promotion programs for Medicare and Medicaid recipients.

BUSINESS PRIORITIES AND HEALTH

One of the challenges in population health is that no single entity feels ownership of, or has responsibility or accountability for, taking con-

________________

2 Latest Census figures show 317 million people live in the United States, but the figure of 310 million was used as the basis for the speaker’s back-of-the-envelope calculation.

FIGURE 3-3 Funding flow from organizations that benefit from improved population health to organizations that can engage people in effective programs. The majority of funding would come from employers. The U.S. Treasury would contribute funding from taxes. Estimates of funding allocations to recipient organizations are based on $200 per person per year.

NOTE: CMS = Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services.

SOURCE: O’Donnell, 2012. Used with permission.

trol and finding solutions, said Baase of Dow. She cited a report from the World Economic Forum on global risks that stated, “[T]he mobilization of social forces and people outside of health systems is critical, as it is clear that chronic diseases are affecting social and economic capital globally” (World Economic Forum, 2010, p. 26). The task now is to create collective ownership of population health and to engage people from all sectors, including the business community, she said.

Macroeconomic Concept Model

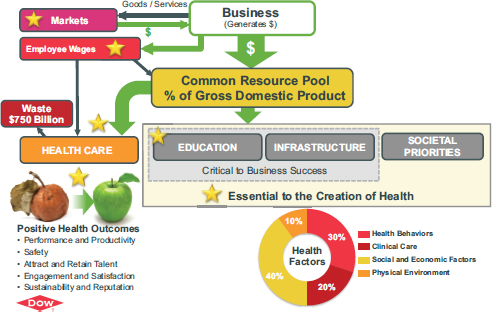

Businesses generate money in society. Some of that money is used to pay employee wages and some percentage of it, in the form of taxes, goes into a common resource pool. Baase used a macroeconomic model to illustrate five key ways in which the current health scenario is negatively impacting the success of the business sector (see Figure 3-4). A better understanding of how these elements are destructive to a business’s suc-

FIGURE 3-4 Macroeconomic concept model illustrating ways in which the current health scenario is negatively affecting the success of the business sector.

SOURCE: Baase presentation, July 30, 2014. Used with permission.

cess could motivate the business community to become more engaged. As summarized by Baase, the five elements are:

- Wage compression Increasing health care costs are resulting in wage compression, that is, a greater percentage of pay is going toward health care benefits versus take-home wages.

- Reduced profits A greater percentage of total generated funds has to be allocated toward health care, resulting in a reduction of profits.

- Eroded foundation for business Money from the common resource pool funds health care as well as education, infrastructure, and other social priorities. Education and infrastructure are essential foundation elements for the success of business, but they are being undermined by the diversion of GDP toward health care. Business also needs healthy people in order to be successful.

- Impact on elements essential to the creation of health The same elements that are essential to business are important social determinants of health. The diversion of spending away from education and infrastructure also undermines the creation of health. This is compounded by the significant waste in health care.

- Diminished purchasing power The cumulative impact of the current scenario is a diminished market because there is less take-home pay and less disposable income.

The Dow Health Strategy

Years ago, Baase said, The Dow Chemical Company’s business case for its health strategy was built on addressing large spending on health care, an inflation rate greater than the consumer price index, high waste in the system, an understanding that prevention can make an impact, and related legislative and regulatory activity. Over time, this evolved toward an understanding that well-designed health strategy elements can advance other corporate priorities, including sustainability, safety, manufacturing reliability, employee performance and engagement, the ability to attract and retain world class talent to the organization, and corporate reputation. This is not health for the sake of health, but health as essential for and inextricably linked to achieving other corporate priorities, Baase explained.

Several years into this strategy Dow recognized that progress toward the vision of health, human performance, and long-term value for Dow could advance further and faster with a community focus beyond the worksite. Baase said that 80 percent of the covered lives on company health plans were not employees but retirees, dependents, and spouses in the community. The Dow health strategy now includes four core pillars focused on culture and environment inside the company as well as in the community: prevention, quality and effectiveness, health care system management, and advocacy. In addition to its corporate health promotion programs, Dow has incorporated a collective impact model into its strategy and has developed a community profile toolkit to define strategic priorities and value. Using publicly available data sources and benchmarks, the company has identified five priority areas for evidence-based interventions.

For Dow, the business case for engagement in population health is broad and strong, Baase concluded. Insightful and effective action is possible, and there are opportunities for high-value actions.

DEVELOPING THE BUSINESS CASE: A HERO INITIATIVE

In its annual reports to Congress the Community Preventive Services Task Force has identified a variety of ways in which community health improvement can benefit multiple stakeholders, including business and industry, Pronk of HealthPartners said. These include reductions in health care spending through lowering the need and demand for health care; a

reduced burden of illness leading to improved function; environmental and policy changes that make healthy choices the easy choices; stable or improved economic states, as healthy communities complement vibrant business and industry; increased healthy longevity; enhanced national security (obesity has become the leading reason for failure of recruitment to the military); and preparation of a healthy future workforce through education and skill building (CPS Task Force, 2014).

Pronk quoted Eccles and colleagues who concluded, “[S]ustainable firms generate higher profits and stock returns, suggesting that developing a corporate culture of sustainability may be a source of competitive advantage for a company in the long-run” (Eccles et al., 2011, p. 30). That means, Pronk said, that a more engaged workforce, a more secure license to operate, a more loyal and satisfied customer base, better relationships with stakeholders, greater transparency, a more collaborative community, and a better ability to innovate are all contributing factors to the potentially superior performance of a company in the long term. Furthermore, workforce health and a connection to the community position a company in a positive light related to long-term sustainability.

Healthy Workplaces, Healthy Communities HERO Initiative

To develop the underlying rationale and business case for companies to invest in community and population health, the Health Enhancement Research Organization (HERO)3 undertook an initiative to document the reasons why employers might want to take an active role in community health initiatives and to identify barriers to engagement. The initiative, titled Healthy Workplaces, Healthy Communities, was co-chaired by Pronk and Baase.

The first phase of the initiative, which was sponsored by the IOM Roundtable on Population Health Improvement, involved a search for community health-related activities being conducted by businesses at the time. The search revealed that many businesses were already engaged in programs that affect community health and wellness (beyond workplace wellness programs). The reasons that businesses offered for engaging in such programs included an enhanced reputation in the community as a good corporate citizen; cost savings that increased over time; job satisfaction for employees; healthier, happier, and more productive employees; and a healthy, vibrant community that draws new talent and retains current staff (HERO, 2014a).

________________

3 The Health Enhancement Research Organization (HERO) is a national leader in employee health management, research, education, policy, strategy, leadership, and infrastructure. See http://hero-health.org (accessed December 12, 2014).

To develop a business case based on the results of the search, the initiative employed a “World Café” process,4 convening more than 50 executives and thought leaders for a 1-day meeting to consider two key questions: (1) What are the strongest elements of a business case that will generate higher levels of employer leadership in improving community health? and (2) What are the most important barriers and limitations that keep employers from playing their critical role in improving community health?

Elements of the Business Case

Seven thematic areas were identified as elements of a business case to engage employers in addressing community health and wellness (HERO, 2014b). As summarized by Pronk, they are:

- Metrics and measurement There is a clear need for common definitions and a set of metrics for the measurement of health relevant for both business and the community.

- Return on investment It is important to present the business case in language that the chief financial officer can relate to, such as saying that investing in the community can lead to greater profits.

- Clear communications When articulating the business case, the messages need to be clear, focused, and relevant. There is a need for different value propositions for different types and sizes of businesses.

- Shared values It is important to understand shared risk and shared values among businesses, communities, and stakeholders (e.g., pooled resources, shared benefits, shared expenses). Recognition is important (e.g., to be seen as an “employer of choice” or a “community of choice”).

- Shared vision Employers and communities need to focus on sustainability with the integration of a culture of health, both internally within the company and externally in the community.

- Shared definitions Define key terms (e.g., what is meant by terms such as “health beyond medical care,” “leader,” or “influence model”).

________________

4 The World Café process uses connected conversations to share knowledge, ignite innovation, and tap into the intelligence of the group. Key elements of the process include small group discussions and informal conversations focused on key questions, sharing ideas and knowledge as participants move among small groups, opportunities to record ideas in words and images, the weaving together of emerging themes and insights, an awareness of the social nature of learning, and noticing that individual conversations are part of and contribute to a larger web through which collective intelligence can become aware of itself (HERO, 2014b).

- Leadership/buy-in Business leaders are needed who can communicate the value of engagement in community health to their peers.

Barriers

The most commonly reported barriers to engagement in community health included a lack of understanding (e.g., what “health” is, why it is important to care about health beyond the workplace, diverse agendas and potential misalignment of multiple stakeholders, who is responsible, and potential benefits and risk); the lack of a strategy, playbook, framework, or model to move forward; the overall complexity of the problem; issues of trust (especially in a competitive business environment); the lack of a common language; return on investment; the lack of metrics; and a lack of leadership buy-in (HERO, 2014b).

Moving Forward

Overall, Pronk summarized, it became clear that there is great variability across employers in the understanding of the rationale for business involvement in community and population health efforts. The cost of health care has become a threat to much needed investments in other social priorities. The need persists for a powerful, yet concise, articulation of the business case for these efforts. Following the acceptance of the business case for such engagement, a roadmap for action will be required to guide “the how and the what.” A shared commitment for action could be generated through processes that, like the HERO World Café, bring people and organizations together, Pronk said.

In the future, the main driver for early engagement of businesses in population health might be compliance with regulatory requirements (e.g., worker safety standards), Pronk concluded. The next level of engagement could stem from corporate charitable giving campaigns, which provide opportunities for companies to be visible in doing good. A more strategic approach to engagement would involve systems to connect health and safety to business value. This may eventually lead to systematic solutions designed to intentionally generate population health and business value and to address the social determinants of health.

In closing, Pronk reiterated some of the benefits that may drive intentional investment in population health, including an enhanced corporate image, increased visibility, stewardship and social responsibility, employer choice, enhanced employee morale, job satisfaction, job fulfillment, teamwork, engaged employees, increased productivity, increased creativity and innovation, the improved attraction and retention of top

talent, reduced illness absences, reduced absenteeism in general, reduced workplace injury, reduced benefits cost (including health care cost as well as short-term and long-term disability and worker’s compensation), better management of an aging workforce, and an increasing awareness and knowledge of self-management and health.

During the discussion that followed, participants considered why business engagement in population health is not more widespread and what could potentially catalyze greater engagement. Pronk suggested that one way to accelerate movement forward would be to identify and define the role of a convener in the community that could bring stakeholders together in a place of respect and trust. Baase reiterated that businesses are already engaged in policy, advocacy, and philanthropy and that they participate on the boards of local community organizations. How can they do this with greater insight toward health? Webber noted that it is often the medium-sized companies that have a real presence in a community and that these companies seem to find it easier to engage in community-wide endeavors than very large, multi-national corporations, even those that might be headquartered in that community. Pronk added that there is much more flexibility in smaller organizations (100 to 200 employees) for engagement.

Participants discussed whether engagement in community health should be mandatory or voluntary. O’Donnell said he did not see how it could be made mandatory. Employers need to be made aware that engagement does not cost them much money and that it has direct, measurable financial benefits, and then they need to be shown how to do it. The more that we appeal to the selfish interests of business, he said, the faster this will get done.

Raymond Baxter of Kaiser Permanente observed that much of the discussion thus far had been on physical health, and he raised the issue of the role of behavioral health in building the connection between business and community. Pronk clarified that his discussion of well-being encompassed the multiple dimensions of emotional, mental, social, career, and physical health as well as meaning and purpose. Baase concurred that she does not consider physical and mental health as separate in these discussions. Dow takes a very comprehensive view of health, she said, and the inclusion of behavioral health is part of the approach, both inside the company and outside in its community work. O’Donnell added that he defines optimal health as including physical, emotional, social, spiritual, and intellectual health.

This page intentionally left blank.