6

Stimulating and Supporting Business Engagement in Health Improvement

After previous panels had considered why businesses should engage in population health and what they can do indirectly and directly to affect population health, speakers in the fourth panel session, moderated by Clinton Foundation fellow Alex Chan, addressed how businesses might engage in population health. George Isham, a senior advisor at HealthPartners, outlined several mechanisms to stimulate and support business engagement in health, including developing a community health business model and acting in the role of an integrator or neutral coordinating entity. Neil Goldfarb, the executive director of the Greater Philadelphia Business Coalition on Health, described his organization as an example of a local business coalition engaged in population health. John Whittington, the lead faculty member for the Institute for Healthcare Improvement’s Triple Aim initiative, described how employers have used the Triple Aim as a framework to improve the health of their own employees and have also applied it via participation in multi-stakeholder coalitions in the communities that they serve.

MECHANISMS FOR ENGAGING BUSINESS IN HEALTH IMPROVEMENT

Progress on health requires collaboration and action on multiple determinants by multiple actors, said Isham of HealthPartners. Isham summarized some of the main reasons for businesses to engage in popu-

lation health,1 including improving their market image in the minds of potential customers (i.e., appearing to be community-minded), improving the value of products and services, improving the health of the workforce (which results in less costly inputs, increased productivity, and improved workforce motivation), improving the community environment for business, attracting more and better customers, increasing wealth in the community, encouraging altruism (social responsibility), improving one’s national business competitiveness, and improving national defense. Ultimately, aligning the self-interest of businesses and the interest of a community needs to be at the core of engagement, Isham said. Appealing to what is important to the stakeholders encourages them to work together toward a common purpose.

Creating Value for the Organization

Isham referred participants to the work of Kaplan and Norton, who laid out strategy maps for creating value from various perspectives (Kaplan and Norton, 2004). In brief, the learning and growth perspective involves considering the internal assets that the organization has (human, informational, and organizational capital). The internal perspective takes into account the processes that create value (operations management processes, customer management processes, innovation processes, and regulatory and social processes). The customer perspective considers those factors that determine value for the customer, including price, quality, availability, selection, functionality, service, partnership, and brand. From the financial perspective, improved cost structure, enhanced customer value, increased asset utilization, and expanded revenue opportunities lead to long-term shareholder value (or strong financials for a nonprofit organization).

Isham highlighted specific areas in the strategy where he suggested that population health could contribute to enhanced value for an organization. Examples include organizational culture and leadership (e.g., the role of the chief executive officer and chief financial officer); human capital (the relationship of the health of the workforce to the community); production and risk management (increased work productivity and safety); environment, safety, and health; employment and community; price and quality of the product; brand and image; improved cost structure; and enhanced customer value. He recommended there be a more critical assessment of where value might be created to make it possible to be more persuasive when presenting the business case and value proposition for population health to business leaders.

________________

1 Making the business case for engagement is discussed in Chapter 3.

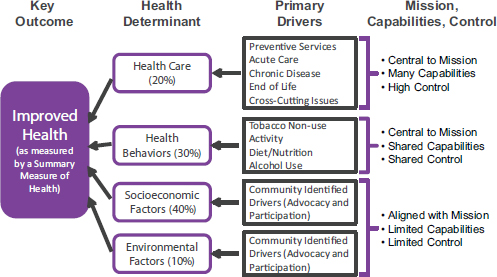

Identifying Where the Organization’s Mission, Capabilities, and Control Lie

In considering which mechanisms could stimulate and support business engagement in health, Isham reminded participants that there are multiple determinants of health outcomes (e.g., health care, health behaviors, socioeconomic factors, and environmental factors) as well as multiple drivers behind each of these determinants (e.g., behavioral drivers might include tobacco or alcohol use, activity level, diet, and nutrition). Using his organization, HealthPartners, as an example, Isham described how the board went through a process to determine which types of drivers of health are central to the HealthPartners mission in terms of improving health and which ones are aligned with the mission, but not central (see Figure 6-1; Kindig and Isham, 2014). As a health care, finance, and delivery organization, HealthPartners finds that the drivers of health care and health behaviors are central to its mission, while the drivers of socioeconomic and environmental factors are aligned with the mission. The board also identified the health determinant for which the organization has many capabilities and high control (health care), the health determinants where it has shared capabilities and shared control (health behaviors), and the health determinants where it has limited capabilities and limited control (socioeconomic and environmental factors). Finally, an

FIGURE 6-1 HealthPartners health driver analysis for priority setting.

SOURCE: Isham presentation, July 30, 2014, adapted from G. Isham and D. Zimmerman, presentation, HealthPartners Board of Directors Retreat, October 2010. Reprinted with permission.

inventory was done of all of the activities that HealthPartners does that touch the various drivers and determinants. This information was then used to set the organization’s priorities and goals.

Isham noted several ways in which businesses directly influence the social determinants of heath. Businesses buy health insurance and can shape the cost and quality of the health care that is delivered through purchasing and benefit design. Businesses can affect healthy behaviors through programs for their workforce, both directly and in partnership with public and private health organizations. In addition to providing employment, businesses affect socioeconomic conditions by contributing to economic development and education, directly and in partnerships. Businesses also affect their environments, for example, by instituting sustainable operations and “green” solutions.

Developing the Community Health Business Model

A business model is the mechanism by which an organization (or collective group) creates, delivers, and captures economic, social, or other forms of value, Isham said. It represents the core aspects of a business (or organization), including its purpose, offerings, strategies, infrastructure, organizational structure, trading practices, operational processes, and policies (Kindig and Isham 2014, p. 5).2 For the sake of discussion, Isham suggested the following list of necessary elements of a community health business model:

- All stakeholders engaged

- Operate in a transparent and public manner

- Leadership structure (in a community health business model)

- Common purpose and defined strategies

- Resources (to implement the community health business model)

- Effective collective and in-kind (direct) evidence-based interventions

- Incentives (moral, regulatory, financial)

- Knowledge of the state of health of the community, and its evolution over time

- Lessons are learned and applied to future efforts

- Commitment and support from government (policies, infrastructure, incentives and information, willingness to engage)

- Encourage dialogue and partnership between public health and broader collaboratives

________________

2 For more on business models, see Johnson et al., 2011.

Isham suggested that the necessary resources for the community health business model might come from savings captured from reducing ineffective health care spending, a better return on investment on policies and programs outside of health care, strengthened government funding for population health improvement, philanthropy, and engagement of corporate business leaders (in particular, from in-kind leadership resources) (Kindig and Isham, 2014).

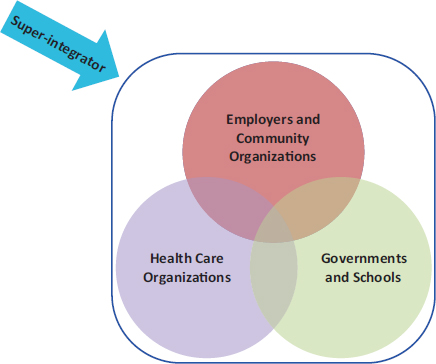

The Role of an Integrator

The concept of an “integrator” (a neutral coordinating entity or mechanism) has been discussed as a way to bring together the various elements and partners in a community health business model (see Figure 6-2; Kindig, 2010; Kindig and Isham, 2014). It has been suggested that the integrator role could be fulfilled by public health agencies (IOM, 2011), health outcome trusts (Kindig, 1997), or accountable health communities (Magnan et al., 2012). Isham said that organizations such as the United Way and the YMCA have also acted as conveners of large community

FIGURE 6-2 Community heath business model: Collaborations and the integrator role.

SOURCE: Kindig and Isham, 2014. Reprinted with permission.

conversations about local health needs. The appropriate convening entity might vary according to regional factors and culture (as was illustrated by Rost and May with, respectively, the Savannah Business Group and Priority Spokane, in Chapter 4). The task now, Isham said, is to develop the collaborative relationship models and examine them critically in terms of how effective the different models are.

Next Steps

In preparation for the roundtable workshop, Isham and Kindig, along with their colleague, Kirstin Q. Siemering, drafted a perspective article that put forth for discussion seven steps that need to be taken to assist businesses in taking a more active role in community health improvement (Kindig et al., 2013). The seven steps are as follows:

- Set galvanizing targets

- Extend a meaningful invitation, soliciting the businesses’ views, needs, and involvement

- Educate chief executive officers and senior executives

- Sponsor meetings with broad community partners

- Develop case studies of businesses that are already making progress in community health

- Promote “Triple Aim”3 collaborations with business

- Identify and create durable revenue streams for population health activities

Ultimately, Isham concluded, businesses need to satisfy their customers’ needs and make a return on investment for their shareholders. They also need to provide good health and health care options, relevant education and skills training, and a good wage to the workforce; provide pressure for cost control and quality in health care; and contribute to a community approach to health.

CASE EXAMPLE: GREATER PHILADELPHIA BUSINESS COALITION ON HEALTH

After having been involved in the National Business Coalition on Health, Neil Goldfarb saw the need for a similar coalition in Philadelphia, and so in January 2012 he launched the Greater Philadelphia Business Coalition on Health (GPBCH). The nonprofit organization currently has 36 employer members, representing 450,000 covered lives locally and

________________

3 The Triple Aim is discussed further by Whittington in this chapter.

more than 1 million lives nationally. There are also 34 affiliate members (health plans, benefits consultants, pharmaceutical companies, and wellness vendors) that join the employers at the table for discussions. The coalition serves five counties in the Philadelphia region as well as northern Delaware and three counties in southern New Jersey. The GPBCH mission, Goldfarb said, is to keep employees healthy and productive in the workplace; to accomplish this, the coalition recognizes that the employees will need health care that is accessible, affordable, high quality, and safe. As examples of business engagement in population health, Goldfarb described three current GPBCH population health initiatives addressing obesity, diabetes, and cancer screening and treatment.

The Philadelphia Health Initiative: Multi-Stakeholder Partnership Addressing Obesity

GPBCH was approached by the pharmaceutical company Sanofi, which was interested in working with other local stakeholders to address obesity as a major problem in the Philadelphia region. The Philadelphia Health Initiative was established as a community collaborative to reduce obesity through an integrated community, workplace, and health care strategy. At the community level, the Philadelphia Health Initiative disseminated the STOP Obesity Alliance Weigh-In Guide, which guides parents in having conversations with their children about healthy weight.4 At the health system level, the goal is to get health centers to lead by example for their own workforces, for the patients they serve, in the curriculum they teach, and for the communities they are in.

At the workplace level, the Diabetes Prevention Learning Collaborative was launched to engage employers in preventing diabetes by recognizing and addressing early risk factors, particularly obesity, in their populations. The learning collaborative facilitates the measurement and sharing of data on obesity and diabetes rates among employers in the region as well as the sharing of practices and experiences (e.g., around benefit designs). Each employer developed and implemented its own customized action plan with guidance with GPBCH. In the first year, 11 employers signed on to the collaborative, and 10 have developed their customized action plans. Goldfarb added that the coalition is promoting the Diabetes Prevention Program of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) as an evidence-based approach to addressing diabetes risk and obesity.

Goldfarb said that even when employers want to put a workplace diabetes prevention program in place, there are barriers at the insurer level

________________

4 See http://www.stopobesityalliance.org/ebook/weighin (accessed December 12, 2014).

(e.g., the credentialing of providers and how to process claims). This is another area where a coalition adds value, so that employers do not have to fight these battles individually.

Value-Based Insurance Design Partnership with the Philadelphia Department of Public Health

GPBCH was also approached by the Philadelphia Department of Public Health, which was eager to engage employers on smoking cessation, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and diabetes. With funding from CDC and the Philadelphia Department of Health, GPBCH developed evidence-based recommendations for how employers could modify their benefit designs to add value and to reduce obstacles to care. Recommendations for benefit designs for smoking cessation, for example, included covering nicotine replacement therapy and not limiting the number of quit attempts covered. Goldfarb said that although there was a lot of interest in the concept from the employers, there has been little movement toward implementation of the value-based designs.

Reducing Disparities in Cancer Screening and Treatment

With seed funding from NBCH, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, and United Health Foundation, GPBCH convened a summit with 40 stakeholders to plan a project around reducing disparities in cancer screening rates. The scope of the project was expanded when it became clear that there were even greater disparities in treatment. Many people who were screened were not able to access care afterward. A plan was developed, Goldfarb said, and GPBCH is currently seeking funding for pilot testing of the plan. The plan involves developing central resources that communities can draw upon to help them implement actions specific to their communities. One size does not fit all, Goldfarb emphasized, and community health planning cannot be done at the aggregate level.

Facilitators and Barriers

In closing, Goldfarb described some facilitators and barriers he has observed in working on these GPBCH initiatives. One barrier is the disconnect between, internally, human resources and internal health benefits management for employees and, externally, the public relations and community relations efforts toward health programs. Goldfarb said that in his experience, the human resources staff do not know who the community relations staff are or on what they are working.

Facilitators

The facilitators Goldfarb mentioned included

- Coalition leadership with population health orientation

- Public health leadership that supports partnership

- Champions among members (members who “get it”)

- Seed funding from external sources

- The participation of large local employers, including public employers

- Partnership with academic programs

- Growing employer recognition that population health issues affect costs and productivity loss

Barriers

Goldfarb’s list of barriers included

- Large corporations reluctant to engage at the local level or to create the perception of geographic inequity

- A lack of evidence for return on investment for interventions

- The disconnect between human resources/benefits and public/community relations departments

- Limited direct access to data, including limited measurement of productivity loss

- Limited “translation” of academic research into actionable policy for employers

- Limited evidence showing links between community health and workforce health and costs

THE TRIPLE AIM AND POPULATION HEALTH MANAGEMENT

The Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) Triple Aim is an approach for optimizing health system performance. As explained by Whittington of the IHI, system designs should simultaneously improve three dimensions: improving the health of populations; improving the patient experience of care, including quality and satisfaction; and reducing the per capita cost of health care. Improving health is what we are all striving for, he added, and per capita spending is one of the key barriers to progress. The Triple Aim initiative is being pursued by 140 organizations around the world, about 50 of which are outside of the United States. Whittington shared some lessons learned (i.e., mechanisms) from working on the Triple Aim initiative.

Foundational Setup for Population Management

To form the foundation for population management, three things must happen simultaneously to essentially form a multi-stakeholder coalition, Whittington said. These are choosing a relevant population for improved health, care, and lowered cost; identifying and developing leadership and governance for the efforts; and articulating a clear purpose that will hold the stakeholders together. He said that target populations can be geographic, such as provinces, regions, or communities, or discrete or defined populations, such as all of the employees of an organization or all the members of a health plan. Once these elements are in place, the next step is to develop a portfolio of projects that will yield results at the scale needed. No single project can accomplish the Triple Aim, he said.

Managing Services for a Population

As Isham had discussed earlier, there is a role for an integrator in bringing together the elements of the portfolio. The integrator could be an organization, Whittington said, but more likely it will be a force for integration made up of multiple actors in a rich multi-stakeholder coalition. The needs of the chosen population segment are assessed, goals are set, and services are designed, coordinated, and delivered at scale. Throughout this progression the integrator’s function is continuously informed by data from feedback loops. Whittington said that many of the services needed by the population segment will likely already exist; they just need to be coordinated better. Community, family, and individual resources also come into play in developing the portfolio of activities that will affect outcomes.

Learning System for Population Management

This kind of work is complex, Whittington said, and it requires a strong learning system. He outlined six characteristics of a learning system for population management: system-level measures, an explicit theory or rationale for system changes, learning by testing, the use of informative cases (act for the individual, learn for the population), learning during scale-up and spread, and people to oversee and manage the learning system.

Business Engagement in Triple Aim Initiatives

Employers have used the Triple Aim as a framework to improve the health of their own employees, Whittington concluded. Employers have also played a role in the multi-stakeholder coalitions in the communities

that they serve. Many were already actively working on health, and others incorporated a health component into existing programs (e.g., community safety programs). Employers have been involved in the implementation of the portfolio projects that were developed by the multi-stakeholder coalitions. Whittington added that employers also indirectly contribute through the service of their executives on community boards (e.g., community boards of nonprofit hospitals). In this way employers can help align the work of the health system with the needs of the community.

Several issues were raised by participants during the open discussion on the mechanisms for engagement, including sustainability, productivity as an aim, the need to work with the key leadership personnel, improving the built environment, and risk adjustment in outcomes measurement.

Sustainability

Moderator Alex Chan asked panelists what programmatic components or structural elements could help ensure that these multi-stakeholder coalitions survive past initial seed funding and are sustained over a long period of time. Goldfarb said that it is a challenge to continue to demonstrate value. Strong leadership is required to keep the coalition together, moving forward, and communicating clearly. It is also important to show progress toward measurable objectives or milestones defined at the outset. Goldfarb said that GPBCH compiles a list every year for its members detailing what was accomplished that year and what still needs to be done. Whittington said that the “why” of the coalition should be explained to businesses at the very beginning and that they should be made to understand that the coalition’s work will be a long-term process. He agreed that there is a need to demonstrate results in order to help keep people engaged. Isham agreed that leadership and demonstrating early results and value for stakeholders are keys to success. It is also important, he said, for the coalition to become embedded in the fabric and culture of the community in terms of what it provides toward health. He added that changes in leadership in the major sponsoring institutions and changes in the leadership of the coalition can be threats to the sustainability of the coalition.

Productivity as a Fourth Aim

Kindig said that the U.S. Department of Defense uses a “quadruple aim,” adding readiness to the Triple Aim. For business, this fourth element could be productivity. Businesses want to have high-performing

employees, and communities want people who are productive. Kindig asked if productivity had been raised in the conversations about the business coalitions. Goldfarb responded that he is trying to interest coalition members in measuring lost productivity in a systematic way. Human resources staff members who work with benefits use direct medical spending to justify their operational budgets, but research shows that indirect costs are greater than direct costs for many diseases. Quantifying indirect costs could help justify health promotion programs. Goldfarb said that most human resources staff are not convinced that lost productivity is a meaningful measure. Because it is self-reported in most cases, there are concerns about bias, but Goldfarb suggested that the bias would be toward underestimating total productivity loss. He said that GPBCH has begun to work with the CFO Alliance on this issue. Chief financial officers have acknowledged that health and productivity are a primary concern, but that message is not reaching the benefits and human resources people. Productivity is a key element of the argument for why businesses should be engaged in health promotion, Isham added. He suggested that there is a need for better measures of productivity.

Engaging Key Corporate Personnel

A participant noted that the person in a company who is most involved in employee and community health and wellness varies according to company structure, size, resources, and culture. In large corporations it might be the corporate medical director, but in many large companies the corporate medical director is focused on occupational health and safety and is not involved in benefits decision making. In small- and medium-sized companies it is often the human resources or benefits personnel who are involved. Goldfarb said that some companies have a full-time wellness director, while others outsource the oversight of their wellness initiatives. Isham noted that the fundamental strategy of a company comes down from the chief executive officer and the board. The argument that improving community health is part of the company’s overall value proposition needs to reach this level of leadership, he said. The various functions within the company (e.g., benefits managers and corporate medical directors) also have a particular interest in that value proposition from various perspectives. Isham also suggested reaching out to business schools and training students in this area. Goldfarb concurred, but noted that the person who is most effective to engage with depends on the company and the culture and on who is in what position.

Baxter pointed out that some companies are rooted in place and are investing in the productivity, health, and safety of a workforce that they have had and intend to have for a very long time. Other businesses are

not rooted in a community and readily relocate for a lower cost of labor, or else have a lot of turnover and a less skilled workforce that they are less likely to invest in. The approach to engaging with these different kinds of organizations must vary in order to appeal to their different self-interests, he said. Isham concurred and warned against over-generalizing the approach to business engagement as a whole. Whittington added that, judging from his experience working in communities and building multi-stakeholder coalitions, there will always be those wanting to make a difference and those who are not invested in the communities.

The Built Environment

A workshop participant emphasized the need to improve the built environment. Isham reiterated that from a business model perspective, a firm needs to identify its assets and capabilities and where it can exert control. For many businesses, smart health care purchasing for their workforces can have significant and direct impacts on health. Improving the environment is more challenging, and business is a partner or a supporter in this area more often than a leader. Goldfarb added that many businesses are addressing the built environment in the workplace, but this does not necessarily translate to the broader built environment of the community. For example, providing bike racks on site does not necessarily mean that employees have safe, paved bike lanes on which to ride to work. This is a next step, he said, adding that he is encouraged that employers are starting to recognize the built environment needs in the workplace.

Risk Adjustment in Outcomes Measurement

A participant raised the issue of provider engagement and pointed to the ongoing debate at the National Quality Forum concerning risk adjustment in outcomes measurement. Such risk adjustment sometimes ends up as a rationalization for differences in outcomes in the measurement of population health. Isham responded that risk adjustment is important for some purposes (e.g., payment for performance). In many other cases, risk adjustment takes away the key issues that we are trying to understand and address (e.g., disparities and other issues in communities). If applied inappropriately, risk adjustment can reduce the pressure that ought to be on all institutions to address these risks. Isham suggested that the push toward simplification and harmonization of measures is compounding the issue. The mindless application of harmonization to either a risk-adjusted or a non-risk-adjusted measure means that we cannot adapt the measure accordingly to circumstances where it is important to understand

the differences. Goldfarb said that outcome measures have to be risk adjusted, particularly if they are to be linked to payment, or to be publishable data. Process measures do not lend themselves to risk adjustment (e.g., health care activities such as whether weight is recorded in the chart, whether obesity is diagnosed, whether treatment is documented in the chart). Process measures can help drive population health.