2

Lessons from the Blue Zones®

The Danish Twin Study established that only about 20 percent of how long the average person lives is dictated by genes, while about 80 percent is influenced by lifestyle and environment, said keynote speaker, Dan Buettner, founder of the concept of Blue Zones®.1 To better understand the role of lifestyle and environment, Buettner set out to “reverse engineer longevity.” In association with National Geographic and with funding from the National Institute on Aging, Buettner and a team of demographers studied census data and identified five pockets where people are living verifiably longer lives by a number of measurements (Ikaria, Greece; Loma Linda, California; Nicoya, Costa Rica; Okinawa, Japan; Sardinia, Italy; see Box 2-1). A team of experts then used established methodologies to try to determine why people had such remarkable longevity in these areas, which were dubbed “blue zones.” The intent, Buettner explained, was to identify lessons or principles that could be applied to build healthier communities and to help people live longer and better lives. In describing the five blue zones, Buettner shared the stories of several individuals, each close to or more than 100 years of age. He showed photos of them swimming, surfboarding, lifting weights, working, and volunteering in their community. Health information is boring, he said, even in the cases of the best research and data. Using a human story to present health information increases audience engagement.

________________

1 See http://www.bluezones.com (accessed December 12, 2014).

Ikaria, Greece The Greek Island of Ikaria has the greatest adherence to the Mediterranean diet in the world. The people live about 7 years longer than Americans do. A survey by the University of Athens of all 674 people over age 70 on the island found, using the same cognitive tests that the National Institute on Aging uses, that Ikarians have one-fifth the rate of dementia as Americans of similar age. Not only are Ikarians healthy, Buettner said, but they are also mentally sharp until the very end. At 80 years old, about 80 percent of Ikarians are still engaged in growing their own food and working at their jobs.

Loma Linda, California A community in Loma Linda, California, with a large concentration of Seventh Day Adventists was identified as a blue zone. The Adventist church promotes a culture of health, emphasizing a healthy diet and exercise, and it operates numerous hospitals and health facilities across the United States and around the world. Buettner said that life expectancy for all women in the United States is about 80 years of age, while for an Adventist it is 89. On average, U.S. men live to 79; however, the life expectancy for male Adventists is 87.

Nicoya, Costa Rica The Nicoya peninsula of Costa Rica has the lowest rate of middle-age mortality in the world, yet Costa Rica spends only 15 percent of what America does on health care. People in Nicoya are more than twice as likely as Americans to reach a healthy age 90, which indicates, Buettner emphasized, that people do not necessarily need to be rich or have the best health care treatment to be healthy.

Okinawa, Japan The archipelago of Okinawa is home to the world’s longest-lived women. In some parts there are up to 30 times more female centenarians per capita than in the United States. Overall, Okinawan women have the longest disability-free life expectancy in the world. They eat a plant-based diet and have strong social networks. Buettner said that Okinawans have no word in their language for retirement and that they stay active into old age.

Sardinia, Italy Sardinia, an island off the coast of Italy with 42,000 people living in 14 villages, has the highest concentration of male centenarians in the world. The population is mostly shepherds, and their diet is mostly plant-based, with some pork. Buettner highlighted their attitude toward aging, which celebrates elders.

SOURCE: Buettner presentation, July 30, 2014.

In meeting numerous centenarians, Buettner realized that in no case did they reach middle age and then decide to pursue longevity through a change in diet, taking up exercise, or finding some nutritional supplement. The longevity occurred because they were in the right environment—an environment that fostered a lifestyle of longevity. Regardless of location, the same nine lifestyle characteristics were identified across all five blue zone environments, which Buettner termed the “Power 9®” principles. Activity, outlook, and diet are key factors, and the foundation underlying behaviors is how people in blue zones connect with others (see Figure 2-1).

Activity

- Move Naturally The world’s longest-lived people do not “exercise.” In blue zones, Buettner’s team observed that people were nudged into moving about every 20 minutes. For example, they were gardening, they kneaded their own bread, and they used hand-operated tools; their houses were not full of conveniences. When they did go out (e.g., to school, work, a friend’s house, a restaurant, or to socialize), it was almost always on foot. Movement is engineered into their daily lives.

FIGURE 2-1 Power 9® principles. Shared traits of the longest-lived people from the five blue zones around the world.

SOURCE: Buettner presentation, July 30, 2104. Used with permission.

Outlook

- Down Shift Stress is part of the human condition, Buettner said, and people in blue zones suffer the same stresses that others do. However, the people living in blue zones have daily rituals that reduce stress and reverse the inflammation associated with stress. Rituals varied and included activities such as prayer, ancestor veneration, napping, and happy hour.

- Purpose In the blue zones, people have vocabulary for purpose. Buettner described a recent study from Canada that followed 6,000 people for 14 years and found that those people who could articulate their sense of purpose had a 15 percent lower risk of dying. Another study, this one from the National Institute on Aging, found that people who could articulate their sense of purpose were living up to 7 years longer.

Diet

- Wine at 5 Except for the Adventists, people in blue zones consumed moderate amounts of alcohol (most commonly two glasses per day, but as much as four glasses per day).

- Plant Slant A meta-analysis by Buettner of 154 dietary surveys in all five blue zones found that 95 percent of 100-year-olds ate plant-based diets, including plenty of beans. Beans are inexpensive, full of fiber and protein, and nutritionally rich, Buettner said. The 100-year-olds also eat a lot of carbohydrates, but in the form of whole grains and sourdough breads rather than in breads leavened with yeast.

- 80 Percent Rule The longest-lived people have strategies to keep themselves from overeating, Buettner said (such as the Confucian mantra some Okinawans use to stop eating when they feel 80 percent full). There is clinical evidence that strategies such as stopping to say a prayer before meals, eating slowly so that the full feeling can reach the brain, not having televisions in kitchens, or eating with family lead to a decrease in food intake. In all five blue zones, people eat a large breakfast and a smaller lunch, and dinner is the smallest meal of the day.

Connections

- Loved Ones First Centenarians spend a lot of time and effort working on their relationships with their spouses and children. Children are likely to keep their aging parents nearby and to

- consider them to be fonts of wisdom that will favor their own survival.

- Belong People in blue zones tend to belong to a faith-based community. Individuals of faith who regularly attend a faith-based service live 4 to 14 years longer than their counterparts who do not, Buettner said.

- Right Tribe Health behaviors are contagious, Buettner said. Deleterious behaviors (e.g., obesity, smoking, excessive drinking, loneliness, unhappiness) are also contagious. They world’s longest-lived people “curate” social circles around themselves that support healthy behaviors.

PRINCIPLES INTO ACTION: LIFE RADIUS

Americans spend more than $100 billion annually on diets, exercise programs and health club memberships, and nutritional supplements, Buettner said. And while proper nutrition and exercise are good, this approach leads to short-term successes and long-term failures. Interventions need to last decades or a lifetime to affect life expectancy and lower rates of chronic disease, he said. Within 3 months of starting a diet, about 10 percent of people will quit. Within 7 months only about 10 percent will remain on the diet, and by 2 years less than 5 percent will still be adhering to the diet. Exercise programs show a similar pattern, Buettner said. Many people start exercise programs after the end-of-year holidays and have quit by autumn. Adherence to daily medication regimens also drops off over time.

With additional funding from National Geographic, Buettner set out to identify populations that were unhealthy but were able to improve their health and to determine what led to lasting improvement. In general, public health initiatives for non-infectious diseases have not been successful, he said. Tens of millions of dollars have been spent on major initiatives (e.g., for heart disease prevention), and while there is sometimes initial success in changing health behaviors, once the spotlight is off and the health researchers and media are gone, people revert to their baseline behaviors. One successful example Buettner did identify took place in North Karelia in Eastern Finland. In 1972 this region had the highest rate of cardiovascular disease in the world. A team led by Pekka Puska reduced the incidence of cardiovascular disease by 80 percent over 30 years and reduced the incidence of cancer by more than 60 percent. Puska’s approach, Buettner explained, focused not on the individual but on the environment and the systems around the individual.

The Life Radius Approach to Optimizing the Living Environment

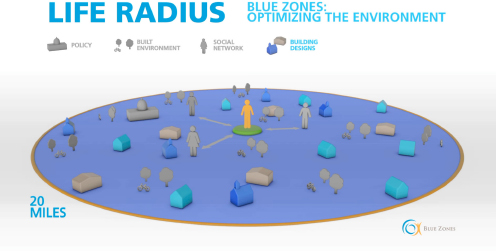

With funding from AARP, Buettner assembled a team of experts to consider how to optimize what he dubbed the life radius—the environment where people spend about 80 percent of their lives (see Figure 2-2). The best investment for optimizing the environment is policy, he said. For example, are fruits and vegetables affordable and accessible, or are fast food and snacks cheapest and most accessible? Do ordinances promote sprawl, or are there incentives for creating livable spaces? Is smoking widely permitted, or more difficult to do? (For instance, consider the difference between West Virginia, where smoking rates are as high as 35 percent, and San Luis Obispo, California, where smoking rates are less than 10 percent.)

Another key factor is the built environment. By making the active option the easy and safe option, the activity level of an entire population can be raised by 30 percent, Buettner said. People increase activity without gym memberships or exercise classes by, for example, walking or biking to school, work, or shopping. Social networks are also important in the life radius, strategically bringing together people who are ready to change their habits and setting up a network to spread the lifestyle. There is also a huge opportunity to affect health through building design, Buettner said. The team identified 120 evidence-based ways that schools, restaurants, grocery stores, workplaces, and other buildings can be set up to nudge people to move more, eat less, eat better, socialize more, smoke less, and

FIGURE 2-2 Life radius. Optimizing the environment where people spend 80 percent of their time.

SOURCE: Buettner presentation, July 30, 2104. Used with permission.

reduce stress. Finally, one factor that is unique to the life radius approach is a focus on purpose. Buettner described workshops on purpose and initiatives to connect people to volunteering, noting that volunteers have lower rates of cardiovascular disease and lower health care costs.

12 Pillars

Taking the life radius approach forward, Buettner and his team focus on 12 “pillars.” The first three pillars are areas in which city governments can make a difference: the built environment, food policy, and tobacco policy. The approach is to start with a conversation, gradually introduce best practices, and ultimately get local leaders to choose 10 priorities and coach them to fruition. This is the best investment and has the biggest impact for the population, Buettner said.

The next six pillars are the places where people spend their day: employers, schools, restaurants, grocery stores, faith organizations, and home. The team developed checklists of revenue-neutral ways that these environments can be optimized for health, and it offers blue zone certification for those that implement a certain number of changes. The last three pillars are programs for creating new social networks, getting people involved in volunteering, and helping them define a sense of purpose.

Case Example: Albert Lea, Minnesota

Albert Lea, Minnesota, was selected from a handful of potential sites for the pilot Blue Zones project. Buettner stressed the importance of having community and leadership buy-in and commitment as well as the need to “listen, not pontificate.” Albert Lea was a beautiful city, but no one could walk anywhere. By connecting sidewalks, people could walk downtown for dinner or to church or schools. Older people did not have to walk through fields or cut across dangerous traffic. Albert Lea originally wanted to widen its main street and raise the speed limit, which, Buettner said, creates stress, danger, noise pollution, and air pollution. Over a series of long conversations, the city agreed to instead put a trail around the lake at the end of the main street. That trail is now busy all of the time with people being active because it is easy, accessible, and pretty, Buettner said. A vast section of the parkland was simply open lawn. The team convinced the city to put in six community gardens, which Buettner said filled up instantly; a seventh garden was added the second year. The gardens are not only a good place for regular, low-intensity physical activity, he said, but a place for people to connect.

Grocery store and restaurant pledges were developed to help change the way people eat. For example, at a blue zone restaurant patrons have

to ask for bread, rather than having it brought to the table automatically. Sandwiches come with fruit, but diners can ask for fries instead. Buettner also described the impact of changing the adjectives on menus. For example, no one wants to order the “healthy choice salad,” but call it the “Italian primavera salad” and sales increase. Restaurants also let diners know that they can order split plates or take leftovers home. The big grocery chain agreed to tag longevity foods and created a blue zone checkout aisle with healthy snacks in the racks. Schools agreed to implement a policy of no eating in hallways or classrooms. A blue zone club was also established, and about 25 percent of the population signed a personal pledge to take action toward achieving a set of personal health and lifestyle goals.

In association with the University of Minnesota, Buettner developed the “vitality compass,” a free tool that lets people calculate their overall life expectancy and three other broad metrics.2 A total of 33 metrics are captured (e.g., what people eat, how often they attend a house of worship, and their body mass index [BMI]). Completing the assessment at baseline and again sometime later after implementing changes can provide a fairly good measurement of impact. Some residents agreed to let blue zone team members come into their homes and optimize their kitchens—for example, with smaller plates, planting gardens, etc. About 1,100 people joined community walking groups (“walking Moai”3), 60 percent of which are still together 5 years later. Residents also attended a purpose-defining class and were quickly matched with volunteer organizations to provide them with an outlet for their newly articulated purpose.

After the first year of the pilot project in Albert Lea, with 3,400 participants (24 percent of the population), entering the participants’ information in the vitality compass program suggested an average life expectancy gain of 3.2 years due to changes in their life habits. Participants also self-reported a collective weight loss of 7,280 pounds. The city of Albert Lea independently reported a 40 percent drop in health care costs for city workers. Buettner noted that some of these figures briefly caught national media attention, but the underlying question is what were the permanent or semi-permanent ways in which the environment or ecosystem was changed.

________________

2 See http://apps.bluezones.com/vitality (accessed December 12, 2014).

3 Moai, pronounced “Mo Eye,” is an Okinawan term that roughly means “meeting for a common purpose.” For more information about walking Moais, see https://www.bluezonesproject.com/moai_events (accessed December 12, 2014).

Creating More Blue Zones

After the Albert Lea pilot project, the Blue Zones project teamed up with Healthways and issued nationwide request for proposals for the next blue zone city. From the 55 cities that applied, the Los Angeles Beach Cities (Hermosa, Redondo, and Manhattan Beach) were selected. After 3 years, the measurement of 80 different facets of well-being (physical and psychological) by Gallup–Healthways showed a 14 percent drop in obesity (compared to a 3 percent drop in obesity across California), a 30 percent drop in smoking, and better self-reported eating habits and increased physical activity.

Buettner said that these results caught the attention of Blue Cross/Blue Shield of Iowa and of the governor of Iowa, Terry Branstad, who invited the Blue Zones project to conduct a publicly supported, privately funded state-wide blue zones initiative. Iowa is a state with a huge pork industry, Buettner pointed out. Instead of trying to address the entire state of 3.2 million people and 995 cities at once, the Blue Zones project set up demonstration cities. Ninety-three cities “auditioned,” and the 10 cities that were most ready for change were selected. Impressive drops in obesity rates and increased health care costs savings are already being observed, and Blue Cross/Blue Shield of Iowa actuaries are calculating a health care savings over a 10-year period of $5 billion due to the establishment of blue zones. New blue zone projects are now starting up in Fort Worth, Texas, and Kauai, Hawaii.

Buettner closed his presentation by sharing some lessons learned from working with 20 cities through six iterations of the project. Scale is the hardest aspect of the project, Buettner said. The first lesson in achieving scale is to start with “ready” communities. Unlike public health, where interventions are targeted at the most at-risk populations, prevention targets the people who are most ready for it. It takes some time to find that readiness, he said, and you have to say no to some communities. Invest in rigorous measurement. “If you can’t measure it, you can’t manage it,” he said, and data are needed to back up the approach. Orchestrate “the perfect storm,” he recommended, engaging the schools, restaurants, grocery stores, city council, and the media, so that everyone is hearing about blue zones everywhere they go. Finally, the process takes time. A workplace may be able to institute effective interventions in 1 year, but communities really need 3 to 5 years, often longer, in part because policy change can be a slow process.

There is no downside to any of the interventions, Buettner concluded. He suggested thinking about programs as an operating system, and striving to make permanent or semi-permanent changes to the system.

The open discussion that followed expanded on the concepts of readiness and scale. Buettner emphasized the value of a few successful demonstration projects in creating broad interest. Engaging everyone at once is generally not successful, he said. When working with communities, one should try to identify those employers who are most committed, and who are willing to commit some of the budget from human resources, marketing, their foundation, or other departments and orchestrate that perfect storm. He added that data on workplaces suggest that the main determinant of whether or not an employee likes his or her job is whether he or she has a best friend at work. Businesses have an enormous opportunity to connect people strategically so that their relationships transcend the commercial or business relationships. Set up those networks internally, make small changes to the policies and the built environment, and measure rigorously. Once you have shown what works, distill that into a scalable model for other companies, starting with the companies that are most ready and most committed, he said.

A participant expressed concern that some of the most at-risk communities may never be as “ready” as Albert Lea and that not including them might exacerbate some of the disparities further. Buettner clarified that blue zones tries to intervene at the whole city level, adding that 15 percent of the population of Albert Lea is Hispanic migrant workers who are very poor. Although the Blue Zones project may not necessarily be working in the poorest neighborhoods, the policy changes made (e.g., de-normalizing tobacco, making healthy foods more accessible and affordable) should benefit all of the communities in a city. Another participant suggested that some of the concepts about readiness are related to equity. How do we create more readiness in communities so that they are more prepared to change? Buettner clarified further that the Blue Zones project does not necessarily assess individual readiness as much as leadership readiness and whether the private and public sectors are open to innovation. Sign-on from the leadership components usually reflects the support of a larger population, he said.

A participant observed that for the original blue zones there was the sense of population homogeneity and a common culture and wondered whether more diversity within a city affects the outcomes. Buettner responded that it is easier if the population is more homogeneous, has a strong sense of civic unity and pride, and speaks a common language. However, the Los Angeles Beach Cities are very diverse and the initiatives have been very successful.