3

Strengthening Health Systems

Key Messages

At the same time that there are acute shortages, these countries also have high unemployment. Clearly there is a mismatch between the health care problem and the production, supply, and employment of health workers.

—Akiko Maeda

Many of [these innovators] have tried to flip the health challenges on its head, [and see these as] really fantastic opportunities for entrepreneurs to think about disruptive technologies, new models of care, and especially novel workforce development programs.

—Krishna Udayakumar

We have a fixation with the old notion of counting heads. … How many patients does a nurse care for in a public setting, in an NGO [nongovernmental organization] setting, in a corporate setting? They vary. So our fixation with counting heads, graduates, licenses, is not very useful. We have to think about other ways of measuring productivity.

—Oscar Picazo

A strong and functional health system is a key element in meeting standards of quality and delivery of care. Health systems differ greatly around the world in terms of organization, principles, culture, funding, staffing, patient population, and many other indicators. Workshop participants discussed some differences and similarities between health systems. They also explored opportunities to increase participation, diffuse innovation, and enhance investment.

TRENDS IN THE HEALTH WORKFORCE1

Akiko Maeda described a number of economic, demographic, and health workforce drivers that are shaping the role of nurses and midwives. Currently, there is a severe and acute shortage of health workers, as the World Health Organization (WHO) and others have noted (WHO and GHWA, 2013). This is true not only for low-income countries, with growing populations and lack of capacity, but also for high-income countries, whose aging population demands additional services while the labor force shrinks. Middle-income countries also face this shortage because of increasing demands from a growing middle class, even while inequities remain.

But at the same time, many countries face high unemployment even while there is a demand for these skilled workers. Maeda remarked that the combination of these two issues indicates there is a substantial gap in economic resources and capacities as countries continue with the same service delivery models and technologies. She postulated that an additional gap in understanding of the problem itself exists, which poses challenges for developing solutions.

In a report highlighting 11 country case studies, Maeda and her colleagues observed that in order to reach a WHO-established minimal threshold for health care worker density, several countries would require huge scale-up and investment (Maeda et al., 2014). This threshold, set at 22.8 workers per 10,000 population, is intended to serve as a proxy for universal health coverage. In some countries they assessed, such as France and Japan, that coverage is met, while in Ethiopia, a 1,000 percent increase would be required. However, Maeda also pointed out that while Thailand is below the threshold (at 17.4 workers per 10,000), it is currently achieving universal health coverage (see Table 3-1). She suggested that the current metric is not necessarily the most useful one because it does not account for different service delivery models and how they are deployed throughout the world.

There is a mismatch, Maeda proposed, between health care workforce shortages and development of health care workers. By examining trends in health professional development, she stated that research indicates increas-

________________

1 This section summarizes information presented by Akiko Maeda, The World Bank.

TABLE 3-1 Health Workforce Estimatesa

| Country | Density of skilled health professionals (doctors, nurses, and midwives) per 10,000 population, circa 2010 | Percentage change in workforce required to reach 22.8 per 10,000 threshold by 2035 |

| Group 1 | ||

|

Bangladesh |

5.7 | 404 |

|

Ethiopia |

2.7 | 1,354 |

| Group 2 | ||

|

Ghana |

13.6 | 221 |

|

Indonesia |

16.1 | 78 |

|

Peru |

22.2 | 33 |

|

Vietnam |

22.3 | 19b |

| Group 3 | ||

|

Brazil |

81.4 | 0 |

|

Thailand |

17.4 | 32 |

|

Turkey |

41.1 | 0 |

| Group 4 | ||

|

France |

126.6 | 0 |

|

Japan |

63.3 | 0 |

NOTE: According to Maeda et al., “Group 1 countries are still setting the national policy agenda for moving toward universal health coverage (UHC); Group 2 countries have made substantial progress toward UHC but still face significant gaps in coverage; those in Group 3 have recently achieved many UHC policy goals but face new challenges in deepening and sustaining coverage; and Group 4 countries have mature health systems with UHC but are still having to adjust national policies to meet changing demographic and economic conditions” (p. 1).

a Health workforce density of 22.8 skilled health professionals per 10,000 population is the lower level recommended by the World Health Organization to achieve relatively high coverage for essential health interventions in countries most in need (WHO, 2006).

b Maeda et al., 2014, authors’ calculation. SOURCE: Maeda et al., 2014.

ing specialization in the health field across high-, middle-, and low-income countries. Owing to technological changes, there is a demand for higher-skilled workers, which requires additional schooling, which then necessitates higher returns for that educational investment (Schumacher, 2002). There are additional market forces, including private for-profit training opportunities and globalization of labor—but these pose a challenge for achieving universal health coverage because they draw resources from primary care and underprivileged populations. It is not enough to train more

doctors and nurses if they are not filling the right gaps, said Maeda. She raised the question of finding ways to continue to move the market while orienting health sector employment toward more socially and publicly necessary domains.

In response to this shortage in the primary care workforce, many countries have expanded midlevel and other categories of health workers. Such workers include physician assistants in the United States, licensed practical nurses in Japan, and health extension workers in Ethiopia. This cadre of workers includes secondary graduates who take on the primary health care role. They require shorter training times and have lower wage expectations, so are considered less expensive. With the deployment of this category of worker, access to health care has expanded, but questions still remain regarding quality of care, regulation, and organizational management. However, even as the number of primary care doctors and nurses has decreased, access to health care is improving in a number of countries, reflecting the impact of these additional midlevel workers. Maeda shared the example of Ethiopia Ministry of Health’s Health Extension Program, which mobilized an additional 30,000 health extension workers to improve basic primary care access.2

The emergence of these midlevel health care workers has had consequences beyond the health care system. In the case of Ethiopia, women make up a large number of these workers, and their entry into the workforce has bolstered their empowerment. Some of them are becoming community activists and leaders because they have education, knowledge, and status. Since the program is only 6 years old, Maeda asserted that it will be important to track the effects on the community of these changes in health delivery and the increased participation of women.

Other effects include the changing composition of the health workforce, which has resulted in resistance from established health professionals such as physicians and nurses. What are the roles of these professionals in these new delivery models? How can these different levels support each other in finding appropriate niches? In particular, Maeda wondered whether these changes in workforce composition and country demographics are also providing opportunities for nurses to play new roles, particularly in community-based care.

She mentioned a few challenges in moving forward with new health care service delivery models, including the lack of data. The existing data are limited and do not reflect the diversity of education, training, and roles played by auxiliary or midlevel health care workers. Another challenge is understanding health worker preferences and behaviors, particularly in

________________

2 For more information about the Ethiopia Ministry of Health’s Health Extension Program, visit http://www.moh.gov.et/hsep (accessed February 4, 2015).

terms of how they respond to new incentives or regulations. She said there is a lack of data about how a health care worker will respond, and behavioral economics could be used to understand health care responses if this data were collected. Finally, she raised the possibility of holding a dialogue around wages and provider payment reforms, as well as other nonmonetary incentives.

SCALING INNOVATION IN HEALTH SYSTEMS3

Krishna Udayakumar described a framework he and his colleagues use for country-level analysis that identifies leading innovators addressing health challenges such as noncommunicable diseases or changing demographics. Udayakumar and colleagues examine organizations that have employed disruptive technologies, new models of care, or workforce development programs to lead improvements in cost, quality, or access to care. He shared a few examples of these innovations.

One Family Health is a business model in sub-Saharan Africa for female nurses who buy into a franchise with a standardized set of training, supply chain, and backstop functions. The model empowers women so they can become entrepreneurs and manage their own clinics.

Lifespring Hospital consists of 15 maternity and childcare facilities in Uttar Pradesh, India. They use principles of the business model Lean Six Sigma, relying on midwives as care providers to provide routine delivery.

Medicall Home is a subscription-based service supported by Mexitel, a national cellphone company. Subscribers have 24-hour access to a call center staffed by nurses and a few physicians. More than 60 percent of inquiries are resolved by phone only, and the others are referred to a network of discount service providers as needed.

Grand-Aides is based in the United States and involves training lay-people to provide community-based primary care and transition from acute to home care under supervision.

Keys to Success

Udayakumar explained that these social enterprises have potential for effecting change in health care delivery and access, as well as empowering women through greater employment participation. He sought to determine what made these programs successful and what could be applied elsewhere. He noted a few “secrets of success.” First, patients should be at the center of providing and improving health and health care, and their consumer

________________

3 This section summarizes information presented by Krishna Udayakumar, International Partnership for Innovative Healthcare Delivery (IPIHD).

patterns and behavior should be tracked. Second, while technology is driving increasing specialization, another trend is the opposite. Mass uptake of technology, like the use of mobile phones, empowers task shifting by allowing workers to provide higher level of services with support. Third, there is potential in transforming the workforce by focusing on competency versus traditional assumptions of the roles of health care professionals. Fourth, reducing variability of care and increasing standardization almost always leads to improved consistency and quality. Lastly, health care tends to be a capital- and resource-intensive sector, so costs can be averted by leveraging existing assets in innovative ways, such as the use of mobile networks as platforms.

Identifying the Gaps

Udayakumar noted that there are also gaps in scaling or replicating these models. First, many of these entrepreneurs are working in isolation from each other, so they cannot readily access one another’s experience. This includes capturing data that can be used for scaling up innovative models in different settings. Second, there is a lack of organizational capability, or business skills, so how can such capacity be built within organizations? Third, a means of creating a more efficient marketplace that permits funding to flow to the right organization at the right time should be explored—in particular, the means by which small and medium enterprises can access the much larger pool of public funds. And finally, entrepreneurs are constrained by their environments, including policy and regulatory restrictions and entrenched health systems.

Responding to a Need

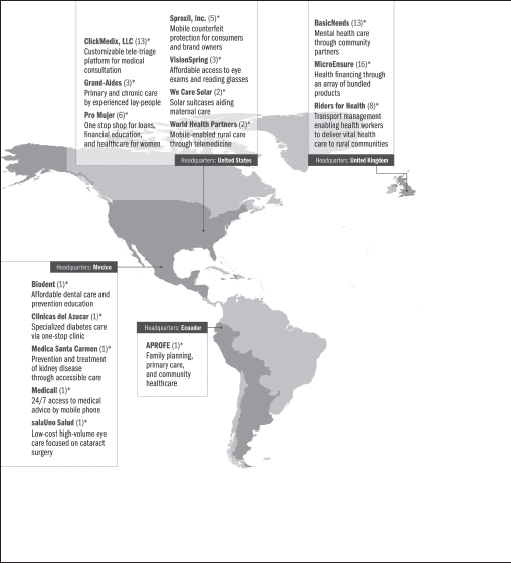

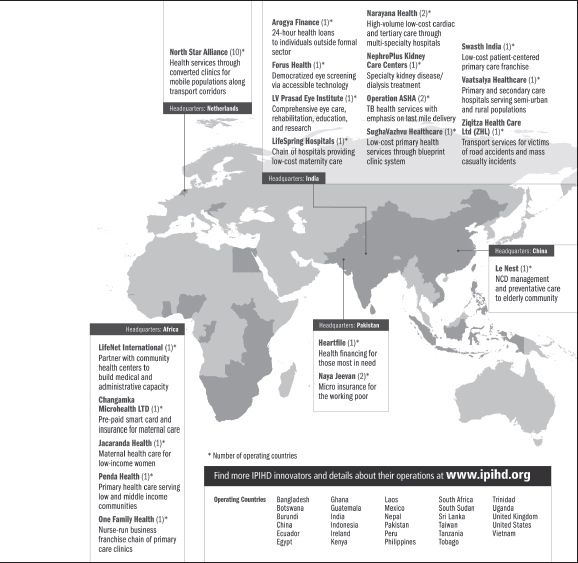

In response to these issues, Udayakumar and his colleagues created a nonprofit organization, International Partnership for Innovative Healthcare Delivery (IPIHD), to develop a platform that could better link entrepreneurs so they can share knowledge, share best practices, and build capacity (see Figure 3-1). He also emphasized the importance of local context; while sharing knowledge and best practices around the world is useful, replication requires careful consideration of the specific context. IPIHD is currently working to prioritize the regions of East Africa and India, where a clustering and an ecosystem of innovation have developed.

Within the larger learning network, Udayakumar highlighted a few working groups with more specific foci. These working groups include several of these innovative programs as well as foundations, corporations, and government agencies who work within the area of focus. He named three: the diabetes working group, the reverse innovation working group, and the

Social Entrepreneurship Accelerator at Duke (SEAD). The diabetes working group brings together about ten innovative organizations that are already deploying technologies and new business models for diabetes diagnosis management and treatment. These organizations, including technology companies or other large organizations such as foundations, are interested in how they can scale diabetes solutions. The second group looks at how to better diffuse across boundaries the good work that is happening on the ground, especially in terms of replication or adaptation of successful models in low- and middle-income countries to high-income countries. The third, SEAD, is a partnership with the Duke business school and the Duke Center for the Advancement of Social Entrepreneurship, where for ten years they have studied how best to scale the impact of social enterprises to determine what a prominent research-based university may contribute to develop a global health accelerator.4

IPIHD is still relatively young, but there is anecdotal evidence of its beneficial effects. Some of the previously mentioned organizations have expanded or have been replicated, and there have been some improvements in providing funding. IPIHD is also implementing another model for scaling up—strategic collaboration. This goes beyond funding or venture capital by leveraging the reach and capacity of large companies. He gave the example of Medtronic, which is using the health platform of ClickMedix as a screening tool for hearing loss among children in India.

Udayakumar closed with further details of the example of One Family Health in Rwanda. Lessons learned in implementing a similar model in Kenya, in which the franchise reached its limit at 80 clinics because of the lack of integration in the public health care sector, informed the creation of a public–private partnership in Rwanda. Working directly with the Ministry of Health, a hub-and-spoke model was created in which the public primary health center was the hub and One Family Health created “spokes” that referred less complex needs to smaller clinics embedded in the community. Because the main clinic was public, the partnership had access to the public financing and subsidy mechanism. It was also able to create a microfinance feature for each franchisee. Additionally, there was seed funding from GlaxoSmithKline to build the initial infrastructure, but once the number of franchises reaches 300, the system will be self-sustaining on franchise fees. Should the model succeed, Udayakumar observed, there could be valuable lessons for those in other countries building similar models. Such systematization of innovation could shape the future of health care delivery.

________________

4 A global health accelerator is a mechanism to capitalize on innovations and expertise in developing countries in order to provide a suite of support services (R4D, n.d.).

FIGURE 3-1 2014 IPIHD Innovator Network.

SOURCES: IPIHD, 2014, and Udayakumar, 2014.

TOWARD A NEW PARADIGM5

In his remarks, Picazo questioned why there is such low emphasis on understanding how technology impacts work, productivity, and training of health professionals. The examples he referred to include eHealth for practices supported by electronic processes and virtual communication as well as electronic health records for data collection, billing, and quality improvement efforts. He considered the impact swipe cards could have on the tasks of nurses and midwives who spend considerable time filling out forms. A cost-savings trend in the United States, he said, is to have administrative tasks such as claims processing outsourced to groups in Eastern Europe, India, South Africa, Turkey, and the Philippines. All of these advances in technology and globalization affect how health workers are or should be trained in the United States and in emerging economies like the Philippines, where there are 10 different electronic medical records currently operating. Along with rapidly changing health care delivery systems, Picazo pointed out that medical tourism is a growing industry. There are now large numbers of patients and consumers crossing national and international borders for health and health care treatments. This has implications for facility planning, considering that it is cheaper to fly a patient to Manila rather than establish a specialty hospital on the Philippine island of Mindanao.

He also noted that the mobility of both patients and health care workers coupled with mobile technologies means that workers and knowledge are more nimble. For example, the use of teleradiology, in which images from remote locations can be digitized and sent to specialists and diagnosticians in central locations, means radiologists and other specialists do not need to be staffed at all hospitals. These changes in the paradigm of health workforce development are also reflected in the need to develop more collaborative, team-based approaches. Not only do tasks shift among different workers and levels in real time, but depending on the setting and outcomes, the composition of these teams is constantly changing.

Picazo also highlighted the intersection of health care and social care; cash transfers are often used to pay for health care services, but traditionally fall under social welfare schemes. This requires greater coordination not only between these two systems at the country level, but also with partners such as nongovernmental organizations and donors. At this intersection is also the flexible role of nurses. They are not always caregivers, Picazo asserted; they can also serve as social workers, among other roles. At the same time, the old model of “counting heads,” as in, how many patients does a health professional care for in a certain setting, is outdated,

________________

5 This section summarizes information presented by Oscar Picazo, Philippine Institute for Development Studies.

and the focus should be on finding other ways to measure productivity. Picazo closed by stating, among all of these elements, that care is bound to culture. Regional or global standards are important, but the influence of culture cannot be separated.

PERSPECTIVES ON STRENGTHENING HEALTH SYSTEMS

In the discussion following the presentations, participants and speakers further explored some of the seminal themes that emerged and raised additional themes. Below are some of the perspectives discussed by individual participants during the discussion6:

- Innovations often best diffuse laterally and not from the top down, inviting room for discussion about better means of dissemination and implementation as well as the use of online platforms for training on program design.

- Investing in tangible infrastructure, such as hospitals, can be more attractive to a government because the return on investment is higher, particularly among a growing middle class. However, reaching to vulnerable and low-income populations is more of a challenge, particularly in the investment space.

- One participant emphasized that seeding investments and sharing innovations should have the aim of scaling up and replicating successful programs, not continuously implementing and testing pilot programs.

REFERENCES

IPIHD (International Partnership for Innovative Healthcare Delivery). 2014. 2014 IPIHD Innovator Network: International partnership for innovative healthcare delivery. Durham, NC: International Partnership for Innovative Healthcare Delivery.

Maeda, A., E. Araujo, C. Cashin, J. Harris, N. Ikegami, M. R. Reich, and The World Bank. 2014. Universal health coverage for inclusive and sustainable development: A synthesis of 11 country case studies. Washington, DC: The World Bank.

R4D (Results for Development Institute). n.d. Global health accelerator. http://healthresearchpolicy.org/content/global-health-accelerator (accessed February 4, 2015).

Schumacher, E. J. 2002. Technology, skills, and health care labor markets. Journal of Labor Research 23(3):397-415.

________________

6 Statements, recommendations, and opinions expressed are those of individual presenters and participants and are not necessarily endorsed or verified by the Institute of Medicine. They should not be construed as reflecting any group consensus.

Udayakumar, K. 2014. Strengthening health systems by scaling innovation. Presented at the IOM workshop: Empowering women and strengthening health systems and services through investing in nursing and midwifery enterprise: Lessons from lower-income countries. Bellagio, Italy, September 9.

WHO (World Health Organization). 2006. The world health report 2006: Working together for health. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO.

WHO and GHWA (Global Health Workforce Alliance) Secretariat. 2013. A universal truth: No health without a workforce. Third global forum on human resources for health report. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO and GHWA.