Mental health and substance use disorders affect approximately 20 percent of Americans and are associated with significant morbidity and mortality. Substantial progress is needed to bring effective interventions to the treatment of those suffering from these disorders. Randomized controlled clinical trials have shown a wide range of psychosocial interventions to be efficacious in treating these disorders, but these interventions often are not being used in routine care. The gap between what is known to be effective and current practice has been defined as a “quality chasm” for health care in general (IOM, 2001) and for mental health and substance use disorders in particular (IOM, 2006). This report details the reasons for this quality chasm in psychosocial interventions for mental health and substance use disorders and offers recommendations for how best to address this chasm by applying a framework that can be used to establish standards for these interventions.

A variety of research approaches are available for establishing a psychosocial intervention as evidence based. Yet the subsequent steps entailed in bringing a psychosocial intervention into routine clinical care are less well defined. The current evidence base for the effects of psychosocial interventions is sizable, and includes thousands of studies on hundreds of interventions. Although many of these interventions have been found to be effective, the supporting data have not been well synthesized, and it can be difficult for consumers, providers, and payers to know what treatments are effective. In addition, implementation issues exist at the levels of providers, provider training programs, service delivery systems, and payers. In the

United States, moreover, there is a large pool of providers of psychosocial interventions, but their training and background vary widely. A number of training programs for providers of care for mental health and substance use disorders (e.g., programs in psychology and social work) do not require training in evidence-based psychosocial interventions, and in those that do require such training (e.g., programs in psychiatry), the means by which people are trained varies across training sites. Some programs provide a didactic in the intervention, while others employ extensive observation and case-based training (Sudak and Goldberg, 2012). Best strategies for updating the training of providers who are already in practice also are not well established. Furthermore, licensing boards do not require that providers demonstrate requisite skills in evidence-based practice (Isett et al., 2007). Even those providers who are trained may not deliver an intervention consistently, and methods for determining whether a provider is delivering an intervention as intended are limited (Bauer, 2002). It also is difficult to track an intervention to its intended outcome, as outcomes used in research are not often incorporated into clinical practice.

Finally, the availability of psychosocial interventions is highly influenced by the policies of payers. The levels of scientific evidence used to make coverage determinations and the types of studies and outcome measures used for this purpose vary widely. Payers currently lack the capacity to evaluate what intervention is being used and at what level of fidelity and quality, nor do they know how best to assess patient/client outcomes. As a result, it is difficult for consumers and payers to understand what they are buying.

Addressing the quality chasm at this time is particularly critical given the recent passage of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) and the Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act (MHPAEA).1 The ACA is aimed at reforming how care is delivered, with an emphasis on accountability and performance measurement, while the MHPAEA is intended to address limits on access to behavioral health care services. Without accepted and endorsed quality standards for psychosocial care, however, there may still be reluctance to promote appropriate use of these treatments. To counter pressures to limit access to psychosocial care, it is critical to promote the use of effective psychosocial interventions and to develop strategies for monitoring the quality of interventions provided.

In this context, the Institute of Medicine (IOM) convened an ad hoc committee to create a framework for establishing the evidence base for

_____________

1 Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act (MHPAEA), amending section 712 of the Employee Retirement Income Security Act of 1974, section 2705 of the Public Health Service Act, and section 9812 of the Internal Revenue Code of 1986, Division C of Public Law 110-343, 110th Congress, 2nd session (October 3, 2008).

psychosocial interventions, and to describe the elements of effective interventions and the characteristics of effective service delivery systems.

This study comes at a time of significant policy change. The enactment of the ACA is creating fundamental changes in the organization, financing, and delivery of health care. The act is intended to make care less fragmented, more efficient, and higher-quality through a number of provisions. Of particular relevance to the subject of this report, through the ACA, several million previously uninsured people have gained coverage for services to treat their mental health and substance use disorders. Health plans offered on the health insurance exchanges must include mental health and substance use services as essential benefits. One early model, developed prior to the ACA’s full enactment, indicated that 3.7 million people with serious mental illness would gain coverage, as would an additional 1.15 million new users with less severe disorders (Garfield et al., 2011).2

In its broadest sense, the goal of the ACA is to achieve patient-centered, more affordable, and more effective health care. One prominent provision is a mandate for a National Quality Strategy,3 which is focused on measuring performance, demonstrating “proof of value” provided by the care delivery system, exhibiting transparency of performance to payers and consumers, linking payment and other incentives/disincentives to performance, establishing provider accountability for the quality and cost of care, and reforming payment methodology (AHRQ, 2011). The National Quality Forum (NQF) was charged by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services to compile, review, and endorse quality measures for use in gauging the quality and effectiveness of health care across many sectors of the health care system (CMS, 2014). Under certain provisions of the ACA, meeting the targets for these quality measures will serve as the basis for payment and for the application of other incentives/disincentives. Among those quality measures addressing mental health and substance use disorders, only two that focus on psychosocial interventions are NQF-endorsed.4

The ACA includes reforms with the potential to mitigate the division of mental health and substance use care between primary and specialty care. The act creates opportunities for large networks of providers to become accountable care organizations (ACOs)5—a care model that directly links

_____________

2 This model assumed that Medicaid expansion would occur in all states, but because of a Supreme Court ruling in 2012, several states have opted out of Medicaid expansion.

3 The National Quality Strategy is a strategic framework for policies designed to improve the quality of care by focusing on specific priorities and long-term goals.

4 Brief alcohol screening and interventions.

5 ACOs are large hospitals and/or physician groups.

care delivery, demonstration of quality, and cost-efficiency. The creation of ACOs will help drive the integration of mental health and substance use services into medical practice and vice versa.

The MHPAEA also has changed the health care landscape specifically for mental health and substance use disorders. The act requires that commercial health insurance plans and plans offered by employers with more than 50 employees that include mental health and substance use coverage place no day and visit limits on services for these disorders (as long as there are no such limits on medical services), and that cost-sharing provisions and annual maximums be set at the predominant level for medical services (HHS, 2013). In addition, MHPAEA regulations require parity for mental health/substance use and medical care in the application of care management techniques such as tiered formularies and utilization management tools. Whereas the MHPAEA deals only with group insurance offered by large employers with 51 or more employees, the ACA extends mental health and substance use coverage to plans offered by small employers and to individuals purchasing insurance through insurance exchanges. The ACA requires that benefit designs adhere to the provisions of the MHPAEA.

The American Psychiatric Association, American Psychological Association, Association for Behavioral Health and Wellness, National Association of Social Workers, National Institutes of Health, the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation within the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, and the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs asked the IOM to convene a committee to develop a framework for establishing standards for psychosocial interventions used to treat mental health and substance use disorders. The committee’s full statement of task is presented in Box 1-1. Reflecting the complexity of this task, the 16-member committee included experts in a variety of disciplines, including psychiatry, psychology, social work, nursing, primary care, public health, and health policy. Members’ areas of expertise encompassed clinical practice, quality and performance measurement, intervention development and evaluation, operation of health systems, implementation science, and professional education, as well as the perspectives of individuals who have been affected by mental health disorders. The scope of this study encompasses the full range of mental health and substance use disorders, age and demographic groups, and psychosocial interventions.

To complete its work, the committee convened for five meetings over the course of 12 months. It held public workshops in conjunction with two of these meetings to obtain additional information on specific aspects of

The Institute of Medicine will establish an ad hoc committee that will develop a framework to establish efficacy standards for psychosocial interventions used to treat mental disorders. The committee will explore strategies that different stakeholders might take to help establish these standards for psychosocial treatments. Specifically, the committee will:

- Characterize the types of scientific evidence and processes needed to establish the effectiveness of psychosocial interventions.

- – Define levels of scientific evidence based on their rigor.

- – Define the types of studies needed to develop quality measures for monitoring quality of psychosocial therapies and their effectiveness.

- – Define the evidence needed to determine active treatment elements as well as their dose and duration.

- Using the best available evidence, identify the elements of psychosocial treatments that are most likely to improve a patient’s mental health and can be tracked using quality measures. In addition, identify features of health care delivery systems involving psychosocial therapies that are most indicative of high-quality care that can be practically tracked as part of a system of quality measures. The following approaches to quality measurement should be considered:

- – Measures to determine if providers implement treatment in a manner that is consistent with evidence-based standards;

- – Measures that encourage continuity of treatment;

- – Measures that assess whether providers have the structures and processes in place to support effective psychotherapy;

- – Consumer-reported experiences of evidence-based psychosocial care; and

- – Consumer-reported outcomes using a measurement-based care approach.

the study charge (see Appendix A for further information). The committee’s conclusions and recommendations are based on its review of the scientific evidence, information gathered in its public workshops, and the expert judgment of its members.

From the outset, it was clear to the committee that there is no generally accepted definition of psychosocial interventions in the literature. The committee offers a definition in this report that includes psychotherapies of various orientations for specific disorders (e.g., interpersonal, cognitive-behavioral, brief psychodynamic) and interventions that enhance outcomes across disorders (e.g., supported employment, supported housing, family

psychoeducation, assertive community treatment, integrated programs for people with dual diagnoses, peer services).

The levels and quality of evidential support vary widely across the myriad psychosocial interventions. This variation reflects a reality in the field. The evidence base for some psychosocial interventions is extensive, while that for others, even some that are commonly used, is more limited. Given the committee’s statement of task, the focus of this report is on evidence-based care, but this emphasis is not intended to discount the fact that many interventions may be effective but have not yet been established as evidence based. The long-term goal is for all psychosocial interventions to be grounded in evidence, and the intent of this study is to advance that goal.

To reflect the diversity in the field, the committee draws on evidence for a variety of approaches when possible. However, cognitive-behavioral therapy is discussed frequently in this report because it has been studied widely as an intervention for a number of mental health and substance use disorders and problems, tends to involve well-defined patient/client populations, has clearly described (i.e., manualized) intervention methods, is derived from a theoretical model, and has clearly defined outcomes. Other approaches have a less extensive evidence base.

In addressing its broad and complex charge, the committee focused on the need to develop a framework for establishing and applying efficacy standards for psychosocial interventions. Over the course of its early meetings, it became clear that the development of this framework would be critical to charting a path toward the ultimate goal of improving the outcomes of psychosocial interventions for those with mental health disorders; the committee also chose to make explicit the inclusion of substance use disorders. In the context of developing this framework, the committee did not conduct a comprehensive literature review of efficacious interventions6 or systematically identify the evidence-based elements of interventions, but rather used the best of what is known about the establishment of an evidence-based intervention to build a framework that would make it possible to fully realize the high-quality implementation of evidence-based interventions in everyday care.

Importantly, the committee intends for the framework to be an iterative one, with the results of the process being fed back into the evidence base and the cycle beginning anew. Much has been done to establish the current

_____________

6 Given the rigor and time involved in conducting a systematic review of the evidence for psychosocial interventions, this task is beyond the purview of the committee. Chapter 4 provides recommendations regarding how these systematic reviews should be conducted. This report also includes discussion of reviews conducted by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, the Veterans Heath Administration, and the U.K. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence that meet the standards put forth in the IOM (2011) report Finding What Works in Health Care: Standards for Systematic Reviews.

evidence base for psychosocial interventions, but much more needs to be done to improve the quality of that evidence base; create new evidence-based interventions; actively engage consumers in this iterative process; train the providers of psychosocial interventions; and ultimately streamline the process of developing, testing, implementing, and disseminating interventions that address the psychosocial needs of those with mental health and substance use problems.

Perhaps the most straightforward aspect of the committee’s charge was to define the levels of scientific evidence based on their rigor. From a simplistic point of view, the randomized controlled trial that compares an active intervention with a credible control condition is the gold standard, offering the best evidence that an intervention is efficacious. But the process of moving an intervention from development to testing for efficacy to effectiveness in the community and ultimately to dissemination requires a variety of different study types, all with their own standards for rigor. For example, the randomized controlled trial often is criticized because researchers enroll participants who may not resemble the people who may ultimately utilize the intervention. Thus studies that evaluate an intervention using real-world practicing clinicians and typical patient and client populations (e.g., effectiveness studies, field trials) increasingly are seen as generating valuable knowledge, although these studies vary in the extent to which traditional rigor is applied, based on the questions being addressed.

Also, more research is needed to understand what intervention is most effective for a given patient subgroup or individual. Emerging lines of research attempt to identify not just whether a specific intervention is effective but what pathway or sequence of intervention steps is most effective for specific clients or patients. Such studies have their own set of standards. Lastly, once an intervention becomes evidence based, it must be studied to determine how best to implement it in the real world, and to disseminate it to and ensure its quality implementation by providers. Such studies do not rely solely on the randomized controlled trial, as the question being addressed may best be answered using a different research method.

While this report addresses the study methods needed to build an evidence base and the best methods for each phase of intervention development, testing, and dissemination, the committee did not attempt to create a compendium of study types and their respective rigor. Rather, the framework is used to emphasize the iterative nature of intervention science and the evolving methodologies that will be required to address the psychosocial needs of individuals with mental health and substance use disorders. In this light, the committee does not define levels of scientific rigor in establishing an intervention as evidence based or specify the many interventions that have crossed the threshold for being identified as evidence based, but emphasizes that its iterative framework should guide the process of estab-

lishing the evidence base for psychosocial interventions and the systems in which those interventions are delivered.

The committee was charged “to identify the evidence needed to determine active treatment elements as well as their dose and duration.” The effort to identify the active elements of psychosocial interventions has a long tradition in intervention development and research in the field of mental health and substance use disorders. Two perspectives emerge from this literature, focused on (1) the nature and quality of the interpersonal relationship between the interventionist and the client/patient, and (2) the content of the interchange between the interventionist and client/patient. Both of these perspectives have been demonstrated to be important components of evidence-based care. The charge to the committee thus requires that both of these traditions be included in its discussion of the active components of evidence-based interventions.

The recommendations offered in this report are intended to assist policy makers, health care organizations, and payers who are organizing and overseeing the provision of care for mental health and substance use disorders while navigating a new health care landscape. The recommendations also target providers, professional societies, funding agencies, consumers, and researchers, all of whom have a stake in ensuring that evidence-based, high-quality care is provided to individuals receiving mental health and substance use services.

OVERVIEW OF MENTAL HEALTH AND SUBSTANCE USE DISORDERS: PREVALENCE, DISABLING EFFECTS, AND COSTS

Mental health disorders encompass a range of conditions, including, for example, neurodevelopmental, anxiety, trauma, depressive, eating, personality, and psychotic disorders. Substance use disorders encompass recurrent use of alcohol and legal or illegal drugs (e.g., cannabis, stimulants, hallucinogens, opioids) that cause significant impairment.

Mental health and substance use disorders are prevalent and highly disabling. The 2009-2010 National Surveys on Drug Use and Health, for example, found that approximately 20 percent of the U.S. population had experienced a mental disorder in the past year and 8.9 percent a substance use disorder (SAMHSA, 2012b). The two often are comorbid, occurring together (Drake and Mueser, 2000). Studies have found that 15 percent of those with a mental disorder in a given year also have a substance use disorder, and 60 percent of those with a substance use disorder in a given year also have a mental disorder (HHS, 1999). The rate of comorbidity of mental, substance use, and physical disorders also is high; approximately 18 percent of cancer patients, for example, have a comorbid mental disorder (Nakash et al., 2014). Comorbidity of any type leads to reduced compliance

with medication, greater disability, and a poorer chance of recovery (Drake and Mueser, 2000). Among diabetics, for example, comorbid depression adversely affects adherence to diet and exercise regimens and smoking cessation, as well as adherence to medications for diabetes, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia (Lin et al., 2004). People with comorbid mental health, substance use, and physical disorders also are at increased risk of premature mortality from a variety of causes (Katon et al., 2008; Thomson, 2011), perhaps because mental health and substance use disorders complicate the management of comorbid chronic medical conditions (Grenard et al., 2011). Depression after a heart attack, for example, roughly triples the risk of dying from a future heart attack, according to multiple studies (Bush et al., 2005).

The World Health Organization’s (WHO’s) Global Burden of Disease Study 2010 evaluates disability across all major causes of disease in 183 countries, using disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs)7 (Whiteford et al., 2013). Findings indicate that mental health and substance use disorders accounted for 7.4 percent of all DALYs and ranked fifth among 10 categories of disease. Further, they ranked first worldwide in years lost to disability, at 22.9 percent (see Table 1-1). Among mental health and substance use disorders, depression was the most disabling, accounting for 40.5 percent of DALYs. Ranking below depression were anxiety disorders (14.6 percent), illicit drug use disorders (10.9 percent), alcohol use disorders (9.6 percent), schizophrenia (7.4 percent), bipolar disorder (7.0 percent), pervasive developmental disorders (4.2 percent), childhood behavioral disorders (3.4 percent), and eating disorders (1.2 percent).

Mental health and substance disorders impose high direct costs for care, as well as indirect costs (Kessler, 2012). It is estimated that in 2005, care for these disorders in the United States cost a total of $135 billion (Mark et al., 2011). They also imposed indirect costs due to reduced productivity in the workplace in the form of absenteeism, “presenteeism” (i.e., attending work with symptoms impairing performance), days of disability, and workplace accidents. Furthermore, mental health and substance use disorders are responsible for decreased achievement by children in school and an increased burden on the child welfare system. These disorders also impose a high burden on the juvenile justice system: fully 60-75 percent of young people in the juvenile justice system have a mental disorder (Teplin et al., 2002). Likewise, approximately 56 percent of state prisoners, 45 percent of federal prisoners, and 64 percent of jail inmates have a mental disorder (BJS, 2006). The rate of substance use disorders, many of which are comor-

_____________

7 DALYs denote the number of years of life lost due to ill health; disability; or early death, including suicide. A DALY represents the sum of years lost to disability (YLDs) and years of life lost (YLLs).

TABLE 1-1 Leading Causes of Disease Burden

| Condition | Proportion of Total DALYs (95% UI) | Proportion of Total YLDs (95% UI) | Proportion of Total YLLs (95% UI) |

| Cardiovascular and circulatory diseases | 11.9% (11.0-12.6) | 2.8% (2.4-3.4) | 51.9% (15.0-16.8) |

| Diarrhea, lower respiratory infections, meningitis, and other common infectious diseases | 11.4% (10.3-12.7) | 2.6% (2.0-3.2) | 15.4% (14.0-17.1) |

| Neonatal disorders | 8.1% (7.3-9.0) | 1.2% (1.0-1.5) | 11.2% (10.2-12.4) |

| Cancer | 7.6% (7.0-8.2) | 0.6% (0.5-0.7) | 10.7% (10.0-11.4) |

| Mental and substance use disorders | 7.4% (6.2-8.6) | 22.9% (18.6-27.2) | 0.5% (0.4-0.7) |

| Musculoskeletal disorders | 6.8% (5.4-8.2) | 21.3% (17.7-24.9) | 0.2% (0.2-0.3) |

| HIV/AIDS and tuberculosis | 5.3% (4.8-5.7) | 1.4% (1.0-1.9) | 7.0% (6.4-7.5) |

| Other noncommunicable diseases | 5.1% (4.1-6.6) | 11.1% (8.2-15.2) | 2.4% (2.0-2.8) |

| Diabetes and urogenital, blood, and endocrine diseases | 4.9% (4.4-5.5) | 7.3% (6.1-8.7) | 3.8% (3.4-4.3) |

| Unintentional injuries other than transport injuries | 4.8% (4.4-5.3) | 3.4% (2.5-4.4) | 5.5% (4.9-5.9) |

NOTE: DALYs = disability-adjusted life-years; UI = uncertainty interval; YLDs = years lived with a disability; YLLs = years of life lost.

SOURCE: Whiteford et al., 2013.

bid with mental disorders, is similarly high among prison inmates (Peters et al., 1998). Still, only 39 percent of the 45.9 million adults with mental disorders used mental health services in 2010 (SAMHSA, 2012a). And according to the National Comorbidity Survey Replication, conducted in 2001-2003, a similarly low percentage of adults with comorbid substance use disorders used services (Wang et al., 2005). States bear a large proportion of the indirect costs of mental health and substance disorders through their disability, education, child welfare, social services, and criminal and juvenile justice systems.

Definition

To guide our definition of psychosocial interventions, the committee built on the approach to defining interventions used in the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials for Social and Psychological Interventions (CONSORT-SPI; Grant, 2014).8

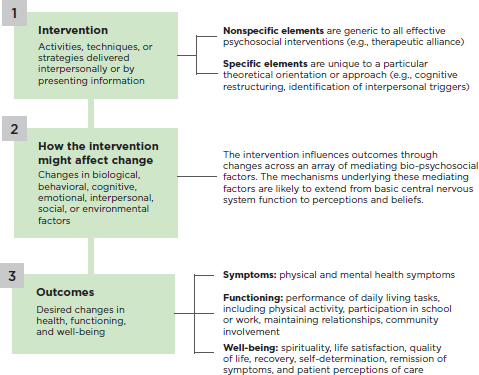

The term “intervention” means “the act or . . . a method of interfering with the outcome or course especially of a condition or process (as to prevent harm or improve functioning)” (Merriam-Webster Dictionary) or “acting to intentionally interfere with an affair so to affect its course or issue” (Oxford English Dictionary). These definitions emphasize two constructs—an action and an outcome. Psychosocial interventions capitalize on psychological or social actions to produce change in psychological, social, biological, and/or functional outcomes. CONSORT-SPI emphasizes the construct of mediators, or the ways in which the action leads to an outcome, as a way of distinguishing psychosocial from other interventions, such as medical interventions (Montgomery et al., 2013). Based on these sources, modified for mental health and substance use disorders, the committee proposes the following definition of psychosocial interventions:

Psychosocial interventions for mental health and substance use disorders are interpersonal or informational activities, techniques, or strategies that target biological, behavioral, cognitive, emotional, interpersonal, social, or environmental factors with the aim of improving health functioning and well-being.

This definition, illustrated in Figure 1-1, incorporates three main concepts: action, mediators, and outcomes. The action is defined as activities, techniques, or strategies that are delivered interpersonally (i.e., a relation-

_____________

8 This text has been updated since the prepublication version of this report.

ship between a practitioner and a client) or through the presentation of information (e.g., bibliotherapy, Internet-based therapies, biofeedback). The activities, techniques, or strategies are of two types: (1) nonspecific elements that are common to all effective psychosocial interventions, such as the therapeutic alliance, therapist empathy, and the client’s hopes and expectations; and (2) specific elements that are tied to a particular theoretical model or psychosocial approach (e.g., communication skills training, exposure tasks for anxiety).

Mediators are the ways in which the action of psychosocial interventions leads to a specific outcome through changes in biological, behavioral, cognitive, emotional, interpersonal, social, or environmental factors; these changes explain or mediate the outcome. Notably, these changes are likely to exert their effects through an array of mechanisms in leading to an outcome (Kraemer et al., 2002), and can extend from basic central nervous system function to perceptions and beliefs.

Finally, outcomes of psychosocial interventions encompass desired changes in three areas: (1) symptoms, including both physical and mental

health symptoms; (2) functioning, or the performance of activities, including but not limited to physical activity, activities of daily living, assigned tasks in school and work, maintaining intimate and peer relationships, raising a family, and involvement in community activities; and (3) well-being, including spirituality, life satisfaction, quality of life, and the promotion of recovery so that individuals “live a self-directed life, and strive to reach their full potential” (SAMHSA, 2012a). Psychosocial interventions have broader societal outcomes as well, such as utilization of acute or institutional services and disability costs. However, these outcomes are not the direct focus of the intervention and therefore are not included in the definition here.

Application of Psychosocial Interventions

The committee’s definition of psychosocial interventions is applicable across a wide array of settings, formats, providers, and populations.

Settings and Formats

The broad range of settings in which psychosocial interventions are delivered includes outpatient clinics, solo provider offices, primary care clinics, schools, client homes, hospitals and other facilities (including inpatient and partial hospital care), and community settings (e.g., senior services, religious services). Some interventions use a combination of office-based and naturalistic sites, and some are designed for specific environments.

While historically, most psychosocial interventions have been delivered in an interpersonal format with face-to-face contact between provider and client, recent real-time delivery formats include telephone, digital devices, and video conferencing, all of which are called “synchronous” delivery. There are also “asynchronous” delivery formats that include self-guided books (bibliotherapy) and computer/Internet or video delivery, with minimal face-to-face contact between provider and client. Some interventions combine one or more of these options. Formats for psychosocial interventions also include individual, family, group, or milieu, with varying intensity (length of sessions), frequency (how often in a specified time), and duration (length of treatment episode).

Providers

Providers who deliver psychosocial interventions include psychologists, psychiatrists, social workers, counselors/therapists, primary care and other nonpsychiatric physicians, nurses, physical and occupational therapists, religious leaders, lay and peer providers, paraprofessionals and caregiv-

ers, and automated providers (e.g., Internet/audio/video-delivered interventions). Combinations of provider options are sometimes used.

Populations

The population targeted by psychosocial interventions is varied. It includes individuals at risk of or experiencing prodromal symptoms of an illness; individuals with acute disorders; individuals in remission, maintenance, or recovery phases of disorders; and individuals who are not ill but are challenged by daily functioning, relationship problems, life events, or psychological adjustment.

Examples of Psychosocial Interventions

There is no widely accepted categorization of psychosocial interventions. The term is generally applied to a broad range of types of interventions, which include psychotherapies (e.g., psychodynamic therapy, cognitive-behavioral therapy, interpersonal psychotherapy, problem solving therapy), community-based treatment (e.g., assertive community treatment, first episode psychosis interventions); vocational rehabilitation, peer support services, and integrated care interventions. The full list, which is too long to reproduce here, consists of interventions from a wide range of theoretical orientations (e.g., psychodynamic, behavioral, social justice, attachment, recovery, and strength-based theories). Each theoretical orientation encompasses a variety of interventions (e.g., within psychodynamic orientations are relational versus ego psychological approaches; within behavioral orientations are cognitive and contingency management approaches). (See Box 1-2 for three examples.)

Efficacy of Psychosocial Interventions

The efficacy of a broad range of psychosocial interventions has been established through hundreds of randomized controlled clinical trials and numerous meta-analyses (Barth et al., 2013; Cuijpers et al., 2010a,b, 2011, 2013; IOM, 2006, 2010). See Chapter 2 for further discussion of evidence-based psychosocial interventions.

Psychosocial interventions often are valuable on their own but also can be combined with other interventions, such as medication, for a range of disorders or problems. In addition, interventions can address psychosocial problems that negatively impact adherence to medical treatments or can deal with the interpersonal and social challenges present during recovery from a mental health or substance use problem. Sometimes multiple psychosocial interventions are employed.

BOX 1-2

Examples of Psychosocial Interventions

Assertive community treatment encompasses an array of services and interventions provided by a community-based, interdisciplinary, mobile treatment team (Stein and Test, 1980). The team consists of case managers, peer support workers, psychiatrists, social workers, psychologists, nurses, and vocational specialists. The approach is designed to provide comprehensive, community-based psychiatric treatment, rehabilitation, and support to persons with serious mental health and substance use disorders, such as bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. A fundamental goal is to provide supports and help consumers develop skills so they can maintain community living, avoid hospitalization, improve their quality of life, and strive for recovery. The core features of assertive community treatment are individualization and flexibility of services based on recovery goals; small caseloads; assertive outreach; ongoing treatment and support, including medication; and 24-hour availability with crisis readiness and a range of psychosocial interventions, such as family psychoeducation, supported employment, dual-disorder substance abuse treatment, and motivational interviewing.

Cognitive-behavioral therapy is used for a wide array of mental health and substance use disorders. It combines behavioral techniques with cognitive psychology—the scientific study of mental processes, such as perception, memory, reasoning, decision making, and problem solving. The goal is to replace maladaptive behavior and faulty cognitions with thoughts and self-statements that promote adaptive behavior (Beck et al., 1979). One example is to replace a defeatist expectation, such as “I can’t do anything right,” with a positive expectation, such as “I can do this right.” Therapy focuses primarily on the “here and now” and imparts a directive or guidance role to the therapist, a structuring of the psychotherapy sessions, and the alleviation of symptoms and patients’ vulnerabilities. Some of the elements of cognitive-behavioral therapy include cognitive restructuring, exposure techniques, behavioral activation, relaxation training, self-monitoring, and relapse prevention.

Contingency management is a psychosocial intervention designed for substance use disorders. As an evidence-based practice based on operant conditioning principles, it uses an incentive-based approach that rewards a client contingent upon meeting desired outcomes. Incentives found to be effective include both voucher/cash equivalents (guaranteed payment) and “prize-based” approaches that feature the chance to earn a large prize, while most chances are low value (Higgins and Silverman, 2008; Stitzer and Petry, 2006).

Not only are psychosocial interventions effective, but patients/clients often prefer them to medications for mental health and substance use disorders when the two approaches have similar efficacy. A recent meta-analysis of 34 studies encompassing 90,483 participants found a threefold higher preference for psychotherapy (McHugh et al., 2013): 75 percent of patients,

especially younger patients and women, preferred psychotherapy. Interventions also can be important to provide an alternative for those for whom medication treatment is inadvisable (e.g., pregnant women, very young children, those with complex medical conditions); to enhance medication compliance, or to deal with the social and interpersonal issues that complicate recovery from mental health and substance use disorders.

Despite patients’ preference for psychosocial interventions, a recent review of national practice patterns shows a decline in psychotherapy and an increase in use of antidepressants (Cherry et al., 2007). From 1998 to 2007, receipt of “psychotherapy only” declined from 15 percent to 10.9 percent of those receiving outpatient mental health care, whereas use of “psychotropic medication only” increased from 44.1 percent to 57.4 percent. The use of combination treatment—both psychotherapy and psychotropic medication—decreased from 40 percent to 32.1 percent (Marcus and Olfson, 2010).

QUALITY CHALLENGES AND THE NEED FOR A NEW FRAMEWORK

The Quality Problem

Quality of care refers to “the degree to which health services for individuals and populations increase the likelihood of desired health outcomes and are consistent with current professional knowledge” (IOM, 1990, p. 21). An IOM committee evaluating mental health counseling services (IOM, 2010) concluded that high-quality care is achieved through a patient-centered system of quality measurement, monitoring, and improvement grounded in evidence.

The quality of care for both physical and mental health and substance use disorders is less than ideal. In a study of 13,275 individuals, researchers from the RAND Corporation searched for quality indicators in medical records (McGlynn et al., 2003). Overall, among patients with a wide array of physical and mental disorders, only 54.9 percent had received recommended care. The nationally representative National Comorbidity Survey Replication found that only 32.7 percent of patients had received at least minimally adequate treatment, based on such process measures as a low number of psychotherapy sessions and medication management visits (Wang et al., 2005). Likewise, only 27 percent of the studies included in a large review of studies published from 1992 to 2000 reported adequate rates of adherence to mental health clinical practice guidelines (Bauer, 2002). In a series of reports, the IOM (1999, 2001, 2006) has called attention to the quality problem: a 2006 IOM report on quality of care for mental health and substance use conditions found that a broad range of evidence-based

psychosocial interventions were not being delivered in routine practice. This problem is especially widespread in primary care, where mental health and substance use disorders often go undetected, untreated, or poorly treated (Mitchell et al., 2009; Wood et al., 2013; Young et al., 2001).

Reasons for the Quality Problem

Some large national organizations (e.g., the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs [VA] health care system [Karlin and Cross, 2014]) have developed their own programs to ensure that evidence-based psychosocial interventions are available in routine care. In general, however, evidence-based psychosocial interventions often are not available as part of routine clinical care for mental health and substance use disorders (IOM, 2006). The fragmentation of care for these disorders is one of the reasons for the quality chasm. Care is characterized by different systems of specialty providers; separation of primary and specialty care; and different state and federal agencies—including health, education, housing, and criminal justice—sponsoring or paying for care. Poor coordination of care can result in unnecessary suffering, excess disability, and earlier death from treatable conditions tied to modifiable risk factors, such as obesity, smoking, substance use, and inadequate medical care (Colton and Manderscheid, 2006).

Fragmentation also occurs in training, with specialty providers being trained in medical schools and in psychology, social work, nursing, and counseling programs. One large survey of a random sample of training directors from accredited training programs in psychiatry, psychology, and social work found that few programs required both didactic and clinical supervision in any evidence-based psychotherapy (Weissman et al., 2006). While a follow-up study has not been published, new developments suggest some improvements. The American Psychiatric Association now urges that evidence of competence in psychodynamic therapy, cognitive-behavioral therapy, brief treatment, and combined treatment with medication be collected in residency training. In its new accreditation standards, still in the public comment stage, the American Psychological Association calls on doctoral training programs to focus on “integration of empirical evidence and practice” (APA, 2015). And the 2008 accreditation standards of the Council on Social Work Education require that social work trainees “employ evidence-based interventions” (CSWE, 2008). Despite these positive steps, however, training programs are given little guidance as to which practices are evidence based, what models of training are most effective, or how the acquisition of core competencies should be assessed (see the full discussion in Chapter 6).

Potential Solutions to the Quality Problem

Potential solutions to the quality problem include identifying the elements of therapeutic change, establishing a coordinated process for reviewing the evidence, creating credentialing standards, and measuring quality of care.

Identifying Elements of Therapeutic Change

For some disorders, such as depression, there are a variety of psychosocial interventions from varying theoretical orientations; for other disorders, such as posttraumatic stress disorder, there are multiple manualized interventions derived from the same theoretical model. Moreover, a number of interventions are adaptations of other interventions targeting different ages, delivery methods (e.g., individual, group), or settings (e.g., primary care, private practice). Considering that most interventions comprise various therapeutic activities, techniques, or strategies (hereafter called “elements”)—some of which are shared across different interventions, even across different theoretical orientations, and some of which are unique to given interventions—the committee recognized the potential value of developing a common terminology for the elements of psychosocial interventions.9 Among other advantages, having such a terminology could facilitate optimally matching the elements of evidence-based interventions to the needs of the individual patient.

In addition to better enabling an understanding of how psychosocial interventions work, the concept of identifying elements has the advantage of making treatments more accessible. Uncovering therapeutic elements that cut across existing interventions and address therapeutic targets across disorders and consumer populations may allow psychosocial interventions to become far more streamlined and easier to teach to clinicians, and potentially make it possible to provide rapid intervention for consumers. The committee also acknowledges the challenges associated with this approach. For example, some interventions may not lend themselves well to an elements approach.

_____________

9 Although this report uses the more familiar word “terminology,” the committee recognizes that the term “ontology” may be helpful in that it describes an added dimension of interconnectedness among elements, beyond simply defining them. This is supported by the IOM (2014) report Capturing Social and Behavioral Domains and Measures in Electronic Health Records: Phase 2.

Establishing a Coordinated Process for Reviewing the Evidence

Building of the evidence base for an elements approach will not occur overnight, and the committee anticipates many years of development before even a few therapeutic elements have been identified. Additionally, methods will be needed for ensuring that those credentialed to deliver an elements approach continue to use the skills in which they are trained. One way to expedite efforts to solve the quality problem would be to identify a process by which evidence on psychosocial interventions could be reviewed objectively using a predetermined set of review standards and the evidence base updated in a reasonable timeframe to reflect the most recent advances in the field. This process would also allow for addressing situations in which evidence is limited and considering different sources of data when the scientific evidence is lacking. Finally, the process would need to be coordinated and organized so as to limit confusion about just what is evidence based. Currently, systematic reviews and guidelines are created by different organizations, using different review standards, and the result can be conflicting information. Having a coordinated body to set the standards and review the evidence base would mitigate this confusion.

Creating Credentialing Standards

Another solution to the quality chasm is to create an agreed-upon set of credentialing standards to ensure that providers are trained to deliver evidence-based practices. As has been the case in the VA and in the United Kingdom’s National Health Service, creating a credentialing process to ensure that providers can deliver evidence-based psychosocial interventions and their elements will require that people and organizations involved in the credentialing process engage in a dialogue to determine what core competencies providers need to provide high-quality interventions, what training practices can best ensure that providers are supported to learn these practices, and whether providers need to be recredentialed periodically. Additionally, research is sorely needed to determine which training practices are effective. Many training practices in current use have not undergone rigorous evaluation, and some practices that are known to be effective (e.g., videotape review of counseling sessions by experts) are expensive and difficult to sustain.

Measuring Quality of Care

The committee determined that it will be necessary to develop measures of quality care for psychosocial interventions to ensure that consumers are

receiving the best possible treatment (see Chapter 5). Research to develop quality measures from electronic health records is one potential means of improving how quality is determined. Research is needed as well to identify practice patterns associated with performance quality. A systematic way to review quality also needs to be established.

The committee identified the following key findings about mental health and substance use disorders and the interventions developed to treat them:

- Mental health and substance use disorders are a serious public health problem.

- A wide variety of psychosocial interventions play a major role in the treatment of mental health and substance use conditions.

- Psychosocial interventions that have been demonstrated to be effective in research settings are not used routinely in clinical practice.

- No standard system is in place to ensure that the psychosocial interventions delivered to patients/consumers are effective.

This report is organized into six chapters. Chapter 2 presents the committee’s framework for applying and strengthening the evidence base for psychosocial interventions. The remaining chapters address in turn the steps in this framework. Chapter 3 examines the elements of therapeutic change that are common to a myriad of psychosocial interventions; the identification and standardization of these elements is the first essential step in strengthening the evidence base for psychosocial interventions. Chapter 4 addresses the standards, processes, and content for the independent evidence reviews needed to inform clinical guidelines. Chapter 5 looks at the development of measures for the quality of care for mental health and substance use disorders. Finally, Chapter 6 explores the levers available to the various stakeholders for improving the outcomes and quality of care. The committee’s recommendations are located at the end of each of these chapters. Table 1-2 shows the chapters in which each component of the committee’s statement of task (see Box 1-1) is addressed.

TABLE 1-2 Elements of the Statement of Task and Chapters Where They Are Addressed

| Element of the Statement of Task | Chapters |

| The Institute of Medicine will establish an ad hoc committee that will develop a framework to establish efficacy standards for psychosocial interventions used to treat mental disorders. The committee will explore strategies that different stakeholders might take to help establish these standards for psychosocial treatments. |

Chapter 2: A Proposed Framework for Improving the Quality and Delivery of Psychosocial Interventions

|

| Characterize the types of scientific evidence and processes needed to establish the effectiveness of psychosocial interventions. Define levels of scientific evidence based on their rigor. |

Chapter 4: Standards for Reviewing the Evidence

|

| Define the types of studies needed to develop performance measures for monitoring quality of psychosocial therapies and their effectiveness. |

Chapter 5: Quality Measurement

|

| Element of the Statement of Task | Chapters |

| Define the evidence needed to determine active treatment elements as well as their dose and duration. |

Chapter 3: The Elements of Therapeutic Change

|

| Using the best available evidence, identify the elements of psychosocial treatments that are most likely to improve a patient’s mental health and can be tracked using quality measures. |

Chapter 3: The Elements of Therapeutic Change

|

| In addition, identify features of health care delivery systems involving psychosocial therapies that are most indicative of high-quality care that can be practically tracked as part of a system of quality measures. |

Chapter 6: Quality Improvement

|

The following approaches to performance measurement should be considered:

|

Chapter 4: Standards for Reviewing the Evidence

|

AHRQ (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality). 2011. Report to Congress: National strategy for quality improvement in health care. http://www.ahrq.gov/workingforquality/nqs/nqs2011annlrpt.pdf (accessed May 27, 2015).

APA (American Psychological Association). 2015. Standards of accreditation for health service psychology. http://www.apa.org/ed/accreditation/about/policies/standards-of-accreditation.pdf (accessed June 18, 2015).

Barth, J., T. Munder, H. Gerger, E. Nuesch, S. Trelle, H. Znoj, P. Juni, and P. Cuijpers. 2013. Comparative efficacy of seven psychotherapeutic interventions for patients with depression: A network meta-analysis. PLoS Medicine 10(5):e1001454.

Bauer, M. S. 2002. A review of quantitative studies of adherence to mental health clinical practice guidelines. Harvard Review of Psychiatry 10(3):138-153.

Beck, A., A. Rush, B. Shaw, and G. Emery. 1979. Cognitive therapy of depression. New York: Guilford Press.

BJS (Bureau of Justice Statistics). 2006. Mental health problems of prison and jail inmates. http://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/mhppji.pdf (accessed March 17, 2014).

Bush, D. E., R. C. Ziegelstein, U. V. Patel, B. D. Thombs, D. E. Ford, J. A. Fauerbach, U. D. McCann, K. J. Stewart, K. K. Tsilidis, and A. L. Patel. 2005. Post-myocardial infarction depression: Summary. AHRQ publication number 05-E018-1. Evidence reports/technology assessment number 123. Rockville, MD: AHRQ.

Cherry, D. K., D. A. Woodwell, and E. A. Rechtsteiner. 2007. National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: 2005 summary. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics.

CMS (Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services). 2014. CMS measures inventory. http://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/QualityMeasures/CMS-Measures-Inventory.html (accessed May 20, 2014).

Colton, C. W., and R. W. Manderscheid. 2006. Congruencies in increased mortality rates, years of potential life lost, and causes of death among public mental health clients in eight states. Preventing Chronic Disease 3(2):A42.

CSWE (Council on Social Work Education). 2008. Educational policy and education standards. http://www.cswe.org/File.aspx?id=13780 (accessed June 18, 2015).

Cuijpers, P., F. Smit, E. Bohlmeijer, S. D. Hollon, and G. Andersson. 2010a. Efficacy of cognitive-behavioural therapy and other psychological treatments for adult depression: Meta-analytic study of publication bias. The British Journal of Psychiatry 196(3):173-178.

Cuijpers, P., A. van Straten, J. Schuurmans, P. van Oppen, S. D. Hollon, and G. Andersson. 2010b. Psychotherapy for chronic major depression and dysthymia: A meta-analysis. Clinical Psychological Review 30(1):51-62.

Cuijpers, P., A. S. Geraedts, P. van Oppen, G. Andersson, J. C. Markowitz, and A. van Straten. 2011. Interpersonal psychotherapy for depression: A meta-analysis. American Journal of Psychiatry 168(6):581-592.

Cuijpers, P., M. Sijbrandij, S. L. Koole, G. Andersson, A. T. Beekman, and C. F. Reynolds. 2013. The efficacy of psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy in treating depressive and anxiety disorders: A meta-analysis of direct comparisons. World Psychiatry 12(2):137-148.

Drake, R. E., and K. T. Mueser. 2000. Psychosocial approaches to dual diagnosis. Schizophrenia Bulletin 26(1):105-118.

Garfield, R. L., S. H. Zuvekas, J. R. Lave, and J. M. Donohue. 2011. The impact of national health care reform on adults with severe mental disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry 168(5):486-494.

Grant, S. 2014. Development of a CONSORT extension for social and psychological interventions. DPhil. University of Oxford, U.K. http://ora.ox.ac.uk/objects/uuid:c1bd46df-eb3f-4dc6-9cc1-38c26a5661a9 (accessed August 4, 2015).

Grenard, J. L., B. A. Munjas, J. L. Adams, M. Suttorp, M. Maglione, E. A. McGlynn, and W. F. Gellad. 2011. Depression and medication adherence in the treatment of chronic diseases in the United States: A meta-analysis. Journal of General Internal Medicine 26(10):1175-1182.

HHS (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services). 1999. Mental health: A report of the Surgeon General. Rockville, MD: HHS, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Mental Health Services, National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Mental Health.

_____. 2013. Final rules under the Paul Wellstone and Pete Domenici Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act of 2008. Federal Register 78(219):68240-68296. http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/FR-2013-11-13/pdf/2013-27086.pdf (accessed May 27, 2015).

Higgins, S. T., and K. Silverman. 2008. Contingency management. In Textbook of substance abuse treatment, 4th ed., edited by M. Galanter and H. D. Kleber. Arlington, VA: The American Psychiatric Press. Pp. 387-399.

IOM (Institute of Medicine). 1990. Medicare: A strategy for quality assurance, Vol. I. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

_____. 1999. To err is human: Building a safer health system. Washington DC: National Academy Press.

_____. 2001. Crossing the quality chasm: A new health system for the 21st century. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

_____. 2006. Improving the quality of care for mental and substance use conditions. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

_____. 2010. Provision of mental health counseling services under TRICARE. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

_____. 2011. Finding what works in health care: Standards for systematic reviews. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

_____. 2014. Capturing social and behavioral domains and measures in electronic health records: Phase 2. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Isett, K. R., M. A. Burnam, B. Coleman-Beattie, P. S. Hyde, J. P. Morrissey, J. Magnabosco, C. A. Rapp, V. Ganju, and H. H. Goldman. 2007. The state policy context of implementation issues for evidence-based practices in mental health. Psychiatric Services 58(7):914.

Karlin, B. E., and G. Cross. 2014. From the laboratory to the therapy room: National dissemination and implementation of evidence-based psychotherapies in the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs health care system. American Psychologist 69(1):19-33.

Katon, W., M. Y. Fan, J. Unutzer, J. Taylor, H. Pincus, and M. Schoenbaum. 2008. Depression and diabetes: A potentially lethal combination. Journal of General Internal Medicine 23(10):1571-1575.

Kessler, R. C. 2012. The costs of depression. Psychiatric Clinics of North America 35(1):1-14.

Kraemer, H. C., G. T. Wilson, C. G. Fairburn, and W. S. Agras. 2002. Mediators and moderators of treatment effects in randomized clinical trials. Archives of General Psychiatry 59(10):877-883.

Lin, E. H., W. Katon, M. Von Korff, C. Rutter, G. E. Simon, M. Oliver, P. Ciechanowski, E. J., Ludman, T. Bush, and B. Young. 2004. Relationship of depression and diabetes self-care, medication adherence, and preventive care. Diabetes Care 27(9):2154-2160.

Marcus, S. C., and M. Olfson. 2010. National trends in the treatment for depression from 1998 to 2007. Archives of General Psychiatry 67(12):1265-1273.

Mark, T. L., K. R. Levit, R. Vandivort-Warren, J. A. Buck, and R. M. Coffey. 2011. Changes in U.S. spending on mental health and substance abuse treatment, 1986-2005, and implications for policy. Health Affairs (Millwood) 30(2):284-292.

McGlynn, E. A., S. M. Asch, J. Adams, J. Keesey, J. Hicks, A. DeCristofaro, and E. A. Kerr. 2003. The quality of health care delivered to adults in the United States. New England Journal of Medicine 348(26):2635-2645.

McHugh, R. K., S. W. Whitton, A. D. Peckham, J. A. Welge, and M. W. Otto. 2013. Patient preference for psychological vs. pharmacologic treatment of psychiatric disorders: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 74(6):595-602.

Mitchell, A. J., A. Vaze, and S. Rao. 2009. Clinical diagnosis of depression in primary care: A meta-analysis. Lancet 374(9690):609-619.

Montgomery, P., S. Grant, S. Hopewell, G. Macdonald, D. Moher, S. Michie, and E. Mayo-Wilson. 2013. Protocol for CONSORT-SPI: An extension for social and psychological interventions. Implementation Science 8(99):1-7.

Nakash, O., I. Levav, S. Aguilar-Gaxiola, J. Alonso, L. H. Andrade, M. C. Angermeyer, R. Bruffaerts, J. M. Caldas-de-Almeida, S. Florescu, G. de Girolamo, O. Gureje, Y. He, C. Hu, P. de Jonge, E. G. Karam, V. Kovess-Masfety, M. E. Medina-Mora, J. Moskalewicz, S. Murphy, Y. Nakamura, M. Piazza, J. Posada-Villa, D. J. Stein, N. I. Taib, Z. Zarkov, R. C. Kessler, and K. M. Scott. 2014. Comorbidity of common mental disorders with cancer and their treatment gap: Findings from the world mental health surveys. Psychooncology 23(1):40-51.

Peters, R. H., P. E. Greenbaum, J. F. Edens, C. R. Carter, and M. M. Ortiz. 1998. Prevalence of DSM-IV substance abuse and dependence disorders among prison inmates. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse 24(4):573-587.

SAMHSA (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration). 2012a. Working definition of recovery. http://store.samhsa.gov/shin/content/PEP12-RECDEF/PEP12RECDEF.pdf (accessed September 17, 2014).

_____. 2012b. State estimates of substance use and mental disorders from the 2009-2010 National Surveys on Drug Use and Health. NSDUH series H-43, HHS publication number (SMA) 12-4673. Rockville, MD: SAMHSA.

Stein, L. I., and M. A. Test. 1980. Alternative to mental hospital treatment. I. Conceptual model, treatment program, and clinical evaluation. Archives of General Psychiatry 37(4):392-397.

Stitzer, M., and N. Petry. 2006. Contingency management for treatment of substance abuse. Annual Reviews of Clinical Psychology 2:411-434.

Sudak, D. M., and D. A. Goldberg. 2012. Trends in psychotherapy training: A national survey of psychiatry residency training. Academic Psychiatry 36(5):369-373.

Teplin, L. A., K. M. Abram, G. M. McClelland, M. K. Dulcan, and A. A. Mericle. 2002. Psychiatric disorders in youth in juvenile detention. Archives of General Psychiatry 59(12):1133-1143.

Thomson, W. 2011. Lifting the shroud on depression and premature mortality: A 49-year follow-up study. Journal of Affective Disorders 130(1-2):60-65.

Wang, P. S., M. Lane, M. Olfson, H. A. Pincus, K. B. Wells, and R. C. Kessler. 2005. Twelvemonth use of mental health services in the United States: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry 62(6):629-640.

Weissman, M. M., H. Verdeli, M. J. Gameroff, S. E. Bledsoe, K. Betts, L. Mufson, H. Fitterling, and P. Wickramaratne. 2006. National survey of psychotherapy training in psychiatry, psychology, and social work. Archives of General Psychiatry 63(8):925-934.

Whiteford, H. A., L. Degenhardt, J. Rehm, A. J. Baxter, A. J. Ferrari, H. E. Erskine, F. J. Charlson, R. E. Norman, A. D. Flaxman, N. Johns, R. Burstein, C. J. Murray, and T. Vos. 2013. Global burden of disease attributable to mental and substance use disorders: Findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet 382(9904):1575-1586. Reprinted with permission from Elsevier.

Wood, E., J. H. Samet, and N. D. Volkow. 2013. Physician education in addiction medicine. Journal of the American Medical Association 310(16):1673-1674.

Young, A. S., R. Klap, C. D. Sherbourne, and K. B. Wells. 2001. The quality of care for depressive and anxiety disorders in the United States. Archives of General Psychiatry 58(1):55-61.