The Elements of Therapeutic Change

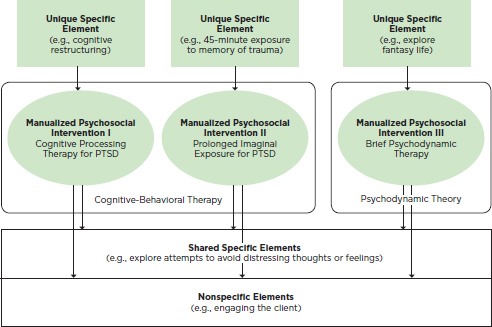

This chapter addresses the elements—therapeutic activities, techniques, or strategies—that make up psychosocial interventions. Most if not all evidence-based, manualized psychosocial interventions are packages of multiple elements (see Figure 3-1). As noted in Chapter 1, nonspecific elements (sometimes referred to as “common factors”) represent the basic ingredients common to most if not all psychosocial interventions, whereas specific elements are tied to a particular theoretical model of change. Development of a common terminology to describe the elements could facilitate research efforts to understand their optimal dosing and sequencing, what aspects of psychosocial interventions work best for whom (i.e., personalized medicine), and how psychosocial interventions effect change (i.e., mechanism of action). This research could iteratively inform training in and the implementation of evidence-based psychosocial interventions.

AN ELEMENTS APPROACH TO EVIDENCE-BASED PSYCHOSOCIAL INTERVENTIONS

Specific and Nonspecific Elements

Some debate exists as to the relative importance of specific and nonspecific elements. A common factors model for psychosocial interventions suggests that nonspecific elements are the most critical to outcomes (Laska et al., 2014), while other models posit that specific elements are critical above and beyond nonspecific elements (that the specific elements explain a unique portion of the variance in the outcomes) (e.g., Ehlers et al., 2010).

The elements that make up evidence-based psychosocial interventions are clearly specified in measures of fidelity, which are used to ascertain whether a given intervention is implemented as intended in research studies and to ensure that practitioners are demonstrating competency in an intervention in both training and practice. Rarely is a psychosocial intervention deemed sufficiently evidence based without a process for measuring the integrity with which the intervention is implemented. Using a Delphi technique, for example, Roth and Pilling (2008) developed a list of elements for cognitive-behavioral therapy for adult anxiety and depression, which was then used for training and testing of fidelity for the U.K. Improving Access to Psychological Therapies program (Clark, 2011). These elements are shown in Box 3-1.

Nonspecific Elements

- Knowledge and understanding of mental health problems

- Knowledge of and ability to operate within professional and ethical guidelines

- Knowledge of a model of therapy and the ability to understand and employ the model in practice

- Ability to engage client

- Ability to foster and maintain a good therapeutic alliance

- Ability to grasp the client’s perspective and world view

- Ability to deal with emotional content of sessions

- Ability to manage endings

- Ability to undertake generic assessment

- Ability to make use of supervision

Specific Elements

- Exposure techniques

- Applied relaxation and applied tension

- Activity monitoring and scheduling

- Using thought records

- Identifying and working with safety behaviors

- Detecting and reality testing automatic thoughts

- Eliciting key cognitions

- Identifying core beliefs

- Employing imagery techniques

- Planning and conducting behavioral experiments

SOURCE: Roth and Pilling, 2008.

The nonspecific elements in a fidelity measure for interpersonal psychotherapy for adolescent depression (Sburlati et al., 2012) are similar, but of course the specific elements differ from those of cognitive-behavioral therapy and reflect the theoretical underpinnings of interpersonal psychotherapy. They include techniques for linking affect to interpersonal relationships (encouragement, exploration, and expression of affect; mood rating; linking mood to interpersonal problems; clarification of feelings, expectations, and roles in relationships; and managing affect in relationships) and interpersonal skills building (communication analysis, communication skills, decision analysis, and interpersonal problem solving skills).

Evidence-based psychosocial interventions for schizophrenia also can be broken down into their elements (Dixon et al., 2010). For example, assertive community treatment for schizophrenia is composed of structural elements including a medication prescriber, a shared caseload among team members, direct service provision by team members, a high frequency of patient contact, low patient-to-staff ratios, and outreach to patients in the community. Social skills training for schizophrenia includes such elements as behaviorally based instruction, role modeling, rehearsal, corrective feedback, positive reinforcement, and strategies for ensuring adequate practice in applying skills in an individual’s day-to-day environment.

Cognitive-behavioral therapy for substance use disorders includes elements of exploring the positive and negative consequences of continued drug use, self-monitoring to recognize cravings early and identify situations that might put one at risk for use, and developing strategies for coping with cravings and avoiding those high-risk situations (e.g., Carroll and Onken, 2005). Another example is family-focused treatment for bipolar disorder, which includes elements of psychoeducation, communication enhancement training, and problem solving (Morris et al., 2007).

Elements have been identified for psychodynamic models of psychosocial intervention that are not limited to a specific disorder or set of symptoms. These include a focus on affect and expression of emotion, exploration of attempts to avoid distressing thoughts and feelings, identification of recurring themes and patterns, discussion of past experience (developmental approach), a focus on interpersonal relations, a focus on the therapy relationship, and exploration of fantasy life (Shedler, 2010). For peer support, specific elements can be identified, such as provision of social support (emotional support, information and advice, practical assistance, help in understanding events), conflict resolution, facilitation of referral to resources, and crisis intervention (along with traditional nonspecific elements) (DCOE, 2011).

Specific Elements That Are Shared

Aside from nonspecific elements that are shared across most if not all psychosocial interventions, some specific elements that derive from particular theoretical models and approaches are shared across multiple psychosocial interventions. This is especially the case for manualized psychosocial interventions that are variants of a single theoretical model or approach (such as the many adaptations of cognitive-behavioral therapy for different disorders or target problems or different sociocultural or demographic characteristics). However, sharing of specific elements also is seen with manuals that represent different theoretical approaches, even though they do not always use the same terminology. For example,

- cognitive-behavioral therapy for social anxiety and interpersonal psychotherapy for depression share the element of “enhanced communication skills”;

- acceptance and commitment therapy, dialectical behavior therapy, and mindfulness-based cognitive therapy share the element of “mindfulness training”;

- a supported employment approach for severe mental illness and problem solving therapy for depression share the element of “behavioral activation”;

- contingency management for substance use disorders and problem solving for depression share the element of “goal setting”;

- contingency management for substance use disorders and parent training for oppositional disorders share the element of “reinforcement”; and

- “exploration of attempts to avoid distressing thoughts and feelings” is an element of psychodynamic therapy that overlaps with the element of psychoeducation regarding avoidance of feared stimuli in cognitive-behavioral therapy.

Obviously, the further apart the theoretical orientations, the less likely it is that shared elements function in the same way across two interventions. For example, exploration of attempts to avoid distressing thoughts and feelings within psychodynamic therapy functions to identify unresolved conflicts, whereas exploration of avoidance of unwanted thoughts or images in cognitive-behavioral therapy provides the rationale for exposure therapy to reduce discomfort and improve functioning. The discussion returns to this issue below.

At the same time, some specific elements differentiate among manualized psychosocial interventions or are unique to a given manual. For example, the element of “the dialectic between acceptance and change” is

FIGURE 3-1 An example of nonspecific and unique and shared specific elements.

NOTE: PTSD = posttraumatic stress disorder.

generally limited to dialectical behavior therapy, while the focus on “grief, role disputes, transitions, or deficits in order to focus patients on linking their current psychosocial situation with their current symptoms” is largely specific to interpersonal psychotherapy and psychodynamic therapy. Exploration of “fantasy life” is likely to be unique to a psychodynamic approach. Of two interventions that address the needs of the seriously mentally ill, one includes the element of “in vivo delivery of services” (assertive community treatment for the seriously mentally ill [Test, 1992]), and the other does not (illness management and recovery [McGuire et al., 2014]). Figure 3-1 depicts nonspecific elements and specific elements that are shared versus unique for different approaches for the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder.

Terminology

Recognition of the elements of evidence-based psychosocial interventions highlights the similarities across interventions as well as the true differences. However, this process of discovery is somewhat hampered by the lack of a common language for describing elements across different

theoretical models and interventions. Examination of fidelity measures from different theoretical models indicates that different terms are used to describe the same element. For example, “using thought records” in cognitive-behavioral therapy is likely to represent the same element as “mood rating” in interpersonal psychotherapy. Sometimes different terms are used by different research groups working within the same theoretical model; in the packaged treatments for severe mental illness, for example, the notion of “individualized and flexible” is highly similar to what is meant by the term “patient-centered.” The field would benefit from a common terminology for identifying and classifying the elements across all evidence-based psychosocial interventions.

ADVANTAGES OF AN ELEMENTS APPROACH

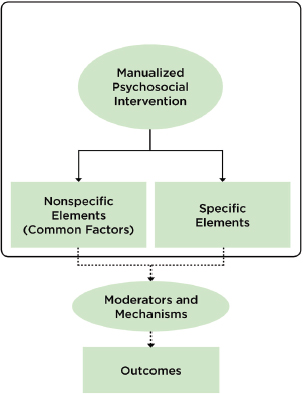

A common terminology for listing elements may offer several advantages for evidence-based psychosocial interventions. A commonly agreed-upon terminology for classifying specific and nonspecific elements would permit researchers to use the same terms so that data could be pooled from different research groups. The result would be a much larger database than can be achieved from independent studies of manualized interventions comprising multiple elements described using different terms. Conceivably, this database could be used to establish optimal sequencing and dosing of elements and to identify for whom a given element, or set of elements, is most effective (i.e., moderation; see below). Elements of medical procedures provide an analogy: many elements are shared across surgical procedures, but surgeries for specific ailments require that the elements be sequenced in particular ways and often in combination with elements unique to an ailment. In addition, it may be possible to connect elements more precisely to purported mechanisms of change than is the case with an entire complex psychosocial intervention. In the future, an elements framework may advance training in and implementation of evidence-based psychosocial interventions. In addition, an elements approach can illuminate both moderators and mediators of the outcomes of interventions (see Figure 3-2).

Moderators

An elements approach for psychosocial interventions may advance the study of moderators of outcome, or what intervention is most effective for a given patient subgroup or individual. The study of moderation is consistent with the National Institute of Mental Health’s (NIMH’s) Strategic Plan for Research, in which a priority is to “foster personalized interventions and strategies for sequencing, or combining existing and novel interventions which are optimal for specific phases of disease progression (e.g.,

FIGURE 3-2 Moderators and mechanisms of outcomes of psychosocial interventions.

prodromal, initial-onset, chronic), different stages of development (e.g., early childhood, adolescence, adulthood, late life), and other individual characteristics” (NIMH, 2015).

Psychosocial interventions comprising multiple specific elements can be problematic when one is studying moderation, because a complex intervention may include elements that are both more or less effective for a given individual. Thus, for example, an individual may respond differentially to the various elements of an intervention for anxiety disorders (e.g., to “cognitive restructuring” versus “exposure therapy”). Similarly, an individual may respond differentially to “mindfulness training” and “valued actions,” which are two elements within acceptance and commitment therapy. At the same time, assessment of moderators of elements (i.e., which element is most effective for a particular patient subgroup) may provide useful information for clinicians and practitioners, enabling them to select from among the array of elements for a given individual. Such investigation could include moderators of elements alone (e.g., for whom exposure to trauma reminders or cognitive reappraisal of trauma is most effective) and of sequences

of elements (e.g., for whom cognitive reappraisal is more effective before than following exposure to trauma reminders). Moderator variables might include (1) the disorder or target problem and (2) sociocultural variables such as age, gender, socioeconomic status, and race/ethnicity. It might also be possible to study biomarkers and “aspects of motivation, cognition, and social behavior that predict clinical response” (NIMH, 2015).

Mechanisms

Mechanisms of action could be investigated for each element or sequence of elements across multiple units of analysis (from genes to behavior), consistent with NIMH’s Research Domain Criteria Initiative (Insel et al., 2010) and its Strategic Plan for Research, which calls for mechanistic research for psychological treatments. For example, an aim of the Strategic Plan is to “develop objective surrogate measures of outcome and clinical change that extend beyond symptoms, to assess if target mechanisms underlying function, general health, and quality of life have been modified by treatments” (NIMH, 2015). The elements of psychosocial interventions themselves are not mediators or mechanisms. However, elements may have the capacity to be tied more precisely to mechanisms than is the case for a complex psychosocial intervention comprising multiple elements. For example, the element of “cognitive restructuring” relates more closely to the mechanism of attentional bias than does a manual comprising cognitive restructuring, relaxation training, and exposure techniques for anxiety disorders. Similarly, the mechanism of social cognition in schizophrenia may be linked more closely to the element of “social skills training” than to the effects of broader intervention packages such as assertive community treatment or supported employment. Knowledge of mechanisms can be used to hone psychosocial interventions to be optimally effective (Kazdin, 2014). In addition, an elements approach could encourage investigation of the degree to which outcomes are mediated by nonspecific versus specific elements. Although both are critical to intervention success, the debate noted earlier regarding the relative importance of each could be advanced by this approach.

A mechanistic approach is not without constraints. The degree to which mechanisms can be tied to particular elements alone or presented in sequence is limited, especially given the potential lag time between the delivery of an intervention and change in either the mediator or the outcome—although this same limitation applies to complex psychosocial interventions comprising multiple elements. Nonetheless, emerging evidence on the role of neural changes as mechanisms of psychological interventions (e.g., Quide et al., 2012) and rapidly expanding technological advances for recording real-time moment-to-moment changes in behavior (e.g., passive recording

of activity levels and voice tone) and physiology (e.g., sleep) hold the potential for much closer monitoring of purported mediators and outcomes that may offer more mechanistic precision than has been available to date.

Intervention Development

The elements approach would not preclude the development of new psychosocial interventions using existing or novel theoretical approaches. However, the approach could have an impact on the development of new interventions in several ways. First, any new intervention could be examined in the context of existing elements that can be applied to new populations or contexts. This process could streamline the development of new interventions and provide a test of how necessary it is to develop entirely novel interventions. Second, for the development of new psychosocial interventions, elements would be embedded in a theoretical model that specifies (1) mechanisms of action for each element (from genes to brain to behavior), recognizing that a given element may exert its impact through more than one mechanism; (2) measures for establishing fidelity; and (3) measures of purported mechanisms and outcomes for each element. Also, new interventions could be classified into their shared and unique elements, providing a way to justify the unique elements theoretically. Finally, the development of fidelity measures could be limited to those unique elements in any new intervention.

Training

When elements are presented together in a single manual, an intervention can be seen as quite complex (at least by inexperienced practitioners). The implementation of complex interventions in many mental health care delivery centers may prove prohibitive, since many such interventions do not get integrated regularly into daily practice (Rogers, 2003). Training in the elements has the potential to be more efficient as practitioners would learn strategies and techniques that can be applied across target problems/disorders or contexts. This approach could lead to greater uptake compared with a single complex intervention (Rogers, 2003), especially for disciplines with relatively less extensive training in psychosocial interventions. Furthermore, many training programs for evidence-based psychosocial interventions already use an elements framework, although currently these frameworks are tied to specific theoretical models and approaches. For example, the comprehensive program for Improving Access to Psychotherapies (IAPT) in the United Kingdom trains clinicians in the elements of cognitive-behavioral therapy, interpersonal psychotherapy, and brief psychodynamic therapy (NHS, 2008). Conceivably, an elements approach

would lead to training in elements of all evidence-based psychosocial interventions, including elements that are shared across these interventions as well as those that are unique to each. In training, each element would (1) be tied to theoretical models with hypothesized mechanisms of action (i.e., a given element may be considered to exert change through more than one purported mechanism); (2) have associated standards for establishing fidelity, which would draw on existing and emerging fidelity measures for evidence-based psychosocial treatment manuals (e.g., Roth and Pilling, 2008; Sburlati et al., 2011, 2012); and (3) be linked with mechanistic and outcome measures.

Implementation

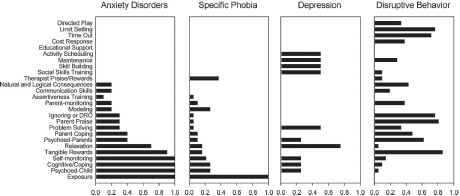

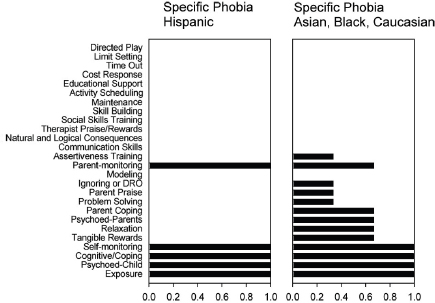

Attempts recently have been made to implement an elements approach for evidence-based psychosocial interventions for children, adolescents, and adults (e.g., Chorpita et al., 2005). One such approach—the Distillation and Matching Model of Implementation (Chorpita et al., 2005) (described in more detail in Chapter 4)—involves an initial step of coding and identifying the elements (i.e., specific activities, techniques, and strategies) that make up evidence-based treatments for childhood mental disorders. For example, evaluation of 615 evidence-based psychosocial treatment manuals for youth yielded 41 elements (Chorpita and Daleiden, 2009). After the elements were identified, they were ranked in terms of how frequently they occurred within evidence-based psychosocial intervention manuals in relation to particular client characteristics (e.g., target problem, age, gender, ethnicity) and treatment characteristics (e.g., setting, format). Focusing on the most frequent elements has the advantage of identifying elements that are the most characteristic of evidence-based psychosocial interventions. Figure 3-3 shows a frequency listing for an array of elements for interventions for anxiety disorders, specific phobia, depression, and disruptive behavior in youth. Figure 3-4 ties the frequency listing for specific phobia to further characteristics of the sample.

In terms of implementation, the matrix of elements (ranked by frequency for different patient characteristics) functioned as a guide for community practitioners, who chose the elements that matched their sample. Whereas Chorpita and colleagues (2005) do not address nonspecific elements (i.e., common factors), an elements approach could encourage practitioners to select nonspecific elements as the foundation of their intervention, and to select specific elements from among those occurring most frequently that have an evidence base for their population (i.e., a personalized approach). With the accrual of evidence, the personalized selection of elements could increasingly be based on research demonstrating which elements, or sequence of elements, are most effective for specific clinical profiles. The

FIGURE 3-3 Intervention element profiles by diagnosis.

NOTE: DRO = differential reinforcement of other behaviors.

SOURCE: Chorpita et al., 2005.

FIGURE 3-4 Intervention element profiles by patient characteristics for the example of specific phobia.

NOTE: DRO = differential reinforcement of other behaviors.

SOURCE: Chorpita et al., 2005.

Distillation and Matching Model of Implementation has been tested, albeit only in youth samples and only by one investigative team. Hence, the results of its application require independent replication.

In a randomized controlled trial, the elements approach was found to outperform usual care and standard evidence-based psychosocial treatment

manuals in both the short term (Weisz et al., 2012) and long term (Chorpita et al., 2013). Also, implementation of an elements approach to training in the Child and Adolescent Mental Health Division of the Hawaii Department of Health resulted in decreased time in treatment and increased rate of improvement (Daleiden et al., 2006). The training in Hawaii was facilitated by a Web-based system that detailed the research literature to help clinicians gather information relevant to their particular needs (i.e., which elements are most frequent in evidence-based treatments for a targeted problem with certain sample characteristics). Because the investigative team derived elements from manualized interventions that are evidence based, and because by far the majority of such interventions for child mental health fall under the rubric of cognitive-behavioral therapy, the elements focused on cognitive-behavioral approaches. However, application of a matrix of elements for all evidence-based psychosocial interventions across all targeted problems/disorders and various sample characteristics (e.g., age, gender, ethnicity/race) is likely to provide a larger array of elements that are not restricted to cognitive-behavioral therapies.

DISADVANTAGES OF AN ELEMENTS APPROACH

The elements approach is more closely aligned with psychological therapies than with other community-based psychosocial interventions. In addition, different levels of abstraction may characterize elements from different theoretical models (e.g., structural elements in assertive community treatment versus content elements in cognitive-behavioral therapy). These distinctions may signal the need for different levels of abstraction in defining and measuring elements across psychosocial interventions. Furthermore, an element does not necessarily equate with an ingredient that is critical or central to the effectiveness of an intervention; determination of which elements are critical depends on testing of the presence or absence of individual elements in rigorous study designs. The result is a large research agenda, given the number of elements for different disorders/problems.

As noted above, the function of a shared specific element (such as exploration of attempts to avoid distressing thoughts and feelings) differs across different theoretical models (such as cognitive-behavioral therapy versus psychodynamic therapy). Thus, an elements approach that distills shared elements across different psychosocial interventions fails to recognize the different theoretical underpinnings of the elements. To address this concern, mechanistic studies could evaluate candidate mediators from different theoretical perspectives.

The existing example of implementation of an elements approach in youth samples relies on frequency counts of elements in evidence-based psychosocial intervention research protocols, and is therefore influenced by

the number of studies using a given element. The result can be a “frequency bias” when one is making general statements about the importance of any given element.

Finally, only those psychosocial interventions deemed evidence based would be included in efforts to identify elements. Consequently, some potentially effective interventions for which efficacy has not been demonstrated would be omitted from such efforts. Also, because some psychotherapy traditions have not emphasized the demonstration of efficacy, the full range of potentially effective elements might not be identified.

The committee recognizes the major gains that have been made to date in demonstrating the efficacy of manualized psychosocial interventions through randomized controlled clinical trials. The committee also recognizes that evidence-based psychosocial interventions comprise therapeutic strategies, activities, and techniques (i.e., elements) that are nonspecific to most if not all interventions, as well as those that are specific to a particular theoretical model and approach to intervention. Furthermore, some elements denoted as specific are actually shared among certain manualized psychosocial interventions, although not always referred to using the same terminology, whereas others are unique. The lack of a common terminology is an impediment to research. The committee suggests the need for research to develop a common terminology that elucidates the elements of evidence-based psychosocial interventions, to evaluate the elements’ optimal sequencing and dosing in different populations and for different target problems, and to investigate their mechanisms. This research agenda may have the potential to inform training in and the implementation of an elements approach in the future. However, it should not be carried out to the exclusion of other research agendas that may advance evidence-based psychosocial interventions.

The committee drew the following conclusion about the efforts to identify the elements of psychosocial interventions:

Additional research is needed to validate strategies to apply elements approaches to understanding psychosocial interventions.

Recommendation 3-1. Conduct research to identify and validate elements of psychosocial interventions. Public and private organizations should conduct research aimed at identifying and validating the ele-

ments of evidence-based psychosocial interventions across different populations (e.g., disorder/problem area, age, sex, race/ethnicity). The development and implementation of a research agenda is needed for

- developing a common terminology for describing and classifying the elements of evidence-based psychosocial interventions;

- evaluating the sequencing, dosing, moderators, mediators, and mechanisms of action of the elements of evidence-based psychosocial interventions; and

- continually updating the evidence base for elements and their efficacy.

Carroll, K. M., and L. S. Onken. 2005. Behavioral therapies for drug abuse. The American Journal of Psychiatry 168(8):1452-1460.

Chorpita, B. F., and E. L. Daleiden. 2009. Mapping evidence-based treatments for children and adolescents: Application of the distillation and matching model to 615 treatments from 322 randomized trials. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 77(3):566.

Chorpita, B. F., E. L. Daleiden, and J. R. Weisz. 2005. Identifying and selecting the common elements of evidence-based interventions: A distillation and matching model. Mental Health Services Research 7(1):5-20.

Chorpita, B. F., J. R. Weisz, E. L. Daleiden, S. K. Schoenwald, L. A. Palinkas, J. Miranda, C. K. Higa-McMillan, B. J. Nakamura, A. A. Austin, and C. F. Borntrager. 2013. Long-term outcomes for the child steps randomized effectiveness trial: A comparison of modular and standard treatment designs with usual care. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 81(6):999. Figures 3-3 and 3-4 reprinted with permission from Springer Science.

Clark, D. M. 2011. Implementing NICE guidelines for the psychological treatment of depression and anxiety disorders: The IAPT experience. International Review of Psychiatry 23(4):318-327.

Daleiden, E. L., B. F. Chorpita, C. Donkervoet, A. M. Arensdorf, and M. Brogan. 2006. Getting better at getting them better: Health outcomes and evidence-based practice within a system of care. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 45(6):749-756.

DCOE (Defense Centers of Excellence). 2011. Best practices identified for peer support programs: White paper. http://www.dcoe.mil/content/Navigation/Documents/Best_Practices_Identified_for_Peer_Support_Programs_Jan_2011.pdf (accessed May 29, 2015).

Dixon, L. B., F. Dickerson, A. S. Bellack, M. Bennett, D. Dickinson, R. W. Goldberg, A. Lehman, W. N. Tenhula, C. Calmes, R. M. Pasillas, J. Peer, and J. Kreyenbuhl. 2010. The 2009 schizophrenia PORT psychosocial treatment recommendations and summary statements. Schizophrenia Bulletin 36(1):48-70.

Ehlers, A., J. Bisson, D. M. Clark, M. Creamer, S. Pilling, D. Richards, P. P. Schnurr, S. Turner, and W. Yule. 2010. Do all psychological treatments really work the same in posttraumatic stress disorder? Clinical Psychology Review 30(2):269-276.

Insel, T., B. Cuthbert, M. Garvey, R. Heinssen, D. S. Pine, K. Quinn, and P. Wang. 2010. Research Domain Criteria (RDoC): Toward a new classification framework for research on mental disorders. The American Journal of Psychiatry 167(7):748-751.

Kazdin, A. E. 2014. Evidence-based psychotherapies I: Qualifiers and limitations in what we know. South African Journal of Psychology doi: 10.1177/0081246314533750.

Laska, K. M., A. S. Gurman, and B. E. Wampold. 2014. Expanding the lens of evidence-based practice in psychotherapy: A common factors perspective. Psychotherapy 51(4):467-481.

McGuire, A. B., M. Kukla, M. Green, D. Gilbride, K. T. Mueser, and M. P. Salyers. 2014. Illness management and recovery: A review of the literature. Psychiatric Services 65(2):171-179.

Morris, C. D., D. J. Miklowitz, and J. A. Waxmonsky. 2007. Family-focused treatment for bipolar disorder in adults and youth. Journal of Clinical Psychology 63(5):433-335.

NHS (U.K. National Health Service). 2008. IAPT implementation plan: National guidelines for regional delivery. http://www.iapt.nhs.uk/silo/files/implementation-plan-national-guidelines-for-regional-delivery.pdf (accessed February 12, 2015).

NIMH (National Institute of Mental Health). 2015. Strategic plan for research. http://www.nimh.nih.gov/about/strategic-planning-reports/NIMH_StrategicPlan_Final_149979.pdf (accessed February 12, 2015).

Quide, Y., A. B. Witteveen, W. El-Hage, D. J. Veltman, and M. Olff. 2012. Differences between effects of psychological versus pharmacological treatments on functional and morphological brain alterations in anxiety disorders and major depressive disorder: A systematic review. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews 36(1):626-644.

Rogers, E. M. 2003. Diffusion of innovations, 5th ed. New York: Free Press.

Roth, A. D., and S. Pilling. 2008. Using an evidence-based methodology to identify the competences required to deliver effective cognitive and behavioural therapy for depression and anxiety disorders. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy 36(2):129-147.

Sburlati, E. S., C. A. Schniering, H. J. Lyneham, and R. M. Rapee. 2011. A model of therapist competencies for the empirically supported cognitive behavioral treatment of child and adolescent anxiety and depressive disorders. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review 14(1):89-109.

Sburlati, E. S., H. J. Lyneham, L. H. Mufson, and C. A. Schniering. 2012. A model of therapist competencies for the empirically supported interpersonal psychotherapy for adolescent depression. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review 15(2):93-112.

Shedler, J. 2010. The efficacy of psychodynamic psychotherapy. American Psychologist 65(2):98.

Test, M. A. 1992. Training in community living. In Handbook of psychiatric rehabilitation, edited by R. P. Liberman. New York: MacMillan. Pp. 153-170.

Weisz, J. R., B. F. Chorpita, L. A. Palinkas, S. K. Schoenwald, J. Miranda, S. K. Bearman, E. L. Daleiden, A. M. Ugueto, A. Ho, J. Martin, J. Gray, A. Alleyne, D. A. Langer, M. A. Southam-Gerow, and R. D. Gibbons. 2012. Testing standard and modular designs for psychotherapy treating depression, anxiety, and conduct problems in youth: A randomized effectiveness trial. Archives of General Psychiatry 69(3):274-282.

This page intentionally left blank.