Standards for Reviewing the Evidence

Reliance on systematic reviews of the evidence base and the development of clinical practice guidelines and implementation tools form the foundation for high-quality health care. However, there is no national, standardized, and coordinated process in the United States for compiling, conducting, and disseminating systematic reviews, guidelines, and implementation materials for use by providers and by those formulating implementation guidance and guidance for insurance coverage. This chapter describes this problem and poses three fundamental questions:

- Who should be responsible for reviewing the evidence and creating and implementing practice guidelines for psychosocial interventions?

- What process and criteria should be used for reviewing the evidence?

- How can technology be leveraged to ensure that innovations in psychosocial interventions are reviewed in a timely fashion and made rapidly available to the public?

As far back as 1982, London and Klerman (1982) suggested that a regulatory body be formed to conduct high-quality systematic reviews for psychosocial interventions, with the aim of providing stakeholders guidance on which practices are evidence based and which need further evaluation. Their proposed regulatory body was patterned after the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), which subjects all medications and most medical devices to a formal review process and grants permission for marketing.

It is this approval process that informs decisions on which medications and devices can be included for coverage by health plans and should be used by providers as effective interventions. While the concept of having a single entity oversee and approve the use of psychosocial interventions has practical appeal, it has not gained traction in the field and has not been supported by Congress (Patel et al., 2001).

In an attempt to address this gap, professional organizations (e.g., the American Psychiatric and Psychological Associations), health care organizations (e.g., Group Health, Kaiser Permanente), federal entities (e.g., the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration’s [SAMHSA’s] National Registry for Evidence-based Programs and Practices [NREPP]), the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs [VA], nonfederal entities (e.g., the Cochrane Review), and various researchers have independently reviewed the literature on psychosocial interventions. However, the result has been sets of guidelines that often are at odds with one another.1 Consequently, clinicians, consumers, providers, educators, and health care organizations seeking information are given little direction as to which reviews are accurate and which guidelines should be employed.

A standardized and coordinated process for conducting systematic reviews and creating practice guidelines and implementation tools has the potential to mitigate confusion in the field. Having such a process is particularly important now given the changes introduced under the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010 (ACA) and the Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act of 2008 (MHPAEA). As discussed in Chapter 1, under the ACA, treatments for mental health and substance use disorders are included among the 10 essential services that must be covered by health plans participating in health insurance exchanges. However, the act provides insufficient information about which psychosocial interventions should be covered, leaving decisions about covered care to be made by payers, including Medicare, Medicaid, and individual health plans. Without a standardized evaluation process to identify important questions, as well as potential controversies, and to then generate reliable information as the basis for policy and coverage decisions, the quality of psychosocial care will continue to vary considerably (Barry et al., 2012; Decker et al., 2013; Wen et al., 2013). A standardized and coordinated process for reviewing evidence and creating practice guidelines would be useful for various stakeholders, including

_____________

1 Existing, well-conducted reviews of the evidence for psychosocial interventions have produced guidelines published by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) (1996), the U.K. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) (2015), and the VA (2015).

- educators who train future clinicians,

- clinicians and clinician subspecialty organizations that guide treatment decisions,

- policy makers who drive legislative decisions,

- governmental entities that oversee licensure and accreditation requirements,

- payers that guide coverage decisions and processes, and

- consumers who wish to be empowered in their treatment choices.

Central to the process of compiling the evidence base for psychosocial interventions is the systematic review process. In 2011, the Institute of Medicine (IOM) offered recommendations for conducting high-quality systematic reviews (IOM, 2011). The guidelines broadly identify evidence-based treatments and approaches in health care but generally are not designed to provide the level of detail needed to inform clinicians in the delivery of treatments to ensure reproducibility and a consistent level of quality outcomes—for example, treatment processes, steps, and procedures, and in some cases the expected timeline for response, “cure,” or remission. In addition, these guidelines do not address how to evaluate the practice components of psychosocial interventions, specifically, or how to identify the elements of their efficacy. As a result, the IOM guidelines will need to be modified for psychosocial interventions to ensure that information beyond intervention impact is available.

An important challenge in creating a standardized process for reviewing evidence is the fact that systematic reviews as currently conducted are laborious and costly, and can rarely keep pace with advances in the field. As a result, reviews do not contain the latest evidence, and so cannot be truly reflective of the extant literature. In the United Kingdom, for example, the guidelines of the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) are updated only every 10 years because of the number of guidelines that need to be produced and the time needed to update the literature, write recommendations, and produce implementation materials (NICE, 2014). Advances in technology may hold the key to ensuring that reviews and the recommendations developed from them are contemporary.

WHO SHOULD BE RESPONSIBLE FOR REVIEWING THE EVIDENCE?

Over the decades, professional organizations, consumer groups, and scientific groups have produced independent systematic reviews, meta-analyses, and practice guidelines for psychosocial interventions. Although these reviews often are helpful to stakeholders, variability in the review processes used by different groups has resulted in conflicting recommenda-

tions even when well-respected organizations have reviewed the same body of evidence. For example, two independent organizations reviewed behavioral treatments for autism spectrum disorders and produced very different recommendations on the use of behavioral interventions for these disorders. The National Standard Project (NSP) reviewed more than 700 studies using a highly detailed rating system—the Scientific Merit Rating Scale—and determined that 11 treatments had sufficient evidence to be considered efficacious (NAC, 2009). During the same time period, however, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) sponsored a systematic review of the same literature and concluded that the evidence was not strong enough to prove the efficacy of any treatments for these disorders (AHRQ, 2011). The reason for these differing recommendations lies in how studies were selected and included in the review: the NSP included single case studies using a special process to rank their validity and quality, while AHRQ eliminated more than 3,406 articles based on its selection criteria, according to which only randomized controlled trials (RCTs) were included, and single case studies with sample sizes of less than 10 were excluded.

Having a standardized, coordinated process for determining which interventions are evidence based for given disorders and conditions could mitigate this problem. Two examples of the benefits of such coordination are NICE in the United Kingdom and the VA’s Evidence-Based Synthesis Program (ESP). Both employ a coordinated process for conducting systematic reviews and creating guidelines based on internationally agreed-upon standards, and both have a process for evaluating the impact of guidelines on practice and outcomes.

NICE is a nonfederal public body that is responsible for developing guidance and quality standards (NICE, 2011; Vyawahare et al., 2014). It was established to overcome inconsistencies in the delivery of health care across regional health authorities in the United Kingdom and Wales. NICE works with the National Health Service (NHS) to ensure high-quality health care, and is responsible for conducting systematic reviews, developing guidelines and recommendations, and creating tools for clinicians to assist in the implementation of care that adheres to the guidelines. NICE’s recommendations encompass health care technologies, treatment guidelines, and guidance in the implementation of best practices. Its guideline process involves a number of steps, with consumers actively engaged at each step (NICE, 2014). A systematic review is called for when the U.K. Department of Health refers a topic for review. A comment period is held so that consumers and clinicians can register interest in the topic. Once there is ample interest, the National Collaborating Center prepares the scope of work and key questions for the systematic review, which are then made available for consumer input. Next, an independent guideline group is formed, consisting of health care providers, experts, and consumers. Internal reviewers within

NICE conduct the systematic review, and the guideline group creates guidelines based on the review. A draft of the guidelines undergoes at least one public comment period, after which the final guidelines are produced, and implementation materials are made available through NHS.

Preliminary reviews of the impact of the NICE process have indicated that it has resulted in positive outcomes for many health disorders (Payne et al., 2013), and in particular for mental health and behavioral problems (Cairns et al., 2004; Pilling and Price, 2006). Recommendations from this body also have informed the credentialing of providers who deliver psychosocial interventions, ensuring that there is a workforce to provide care in accordance with the guidelines (Clark, 2011). In the psychosocial intervention realm, NICE has identified several interventions as evidence based (e.g., brief dynamic therapy, cognitive-behavioral therapy, interpersonal psychotherapy) for a variety of mental health and substance use problems. One result has been the creation of the Increasing Access to Psychotherapies program, charged with credentialing providers in these practices (see Chapter 6 for a full description of this program and associated outcomes).

The VA follows a similar process in creating evidence-based standards through the ESP (VA, 2015). The ESP is charged with conducting systematic reviews and creating guidelines for nominated health care topics. It is expected to conduct these reviews to the IOM standards and in a timely fashion. The VA’s Health Services Research and Development division funds four ESP centers, which have joint Veterans Health Administration (VHA) and university affiliations. Each center director is an expert in the conduct of systematic reviews, and works closely with the AHRQ Evidence-based Practice Centers (EPCs) to conduct high-quality reviews and create guidance and implementation materials for clinicians and the VA managers. The process is overseen by a steering committee whose mission is to ensure that the program is having an impact on the quality of care throughout the VA. Regular reviews of impact are conducted with the aim of continuing to improve the implementation process. A coordinating center monitors and oversees the systematic review process, coordinates the implementation of guidelines, and assists stakeholders in implementation and education.

The ESP model has been highly effective in improving the implementation of psychosocial interventions in the VA system (Karlin and Cross, 2014a,b). To date, several evidence-based psychotherapies have been identified and subsequently implemented in nearly every VA facility throughout the United States (see Chapter 6 for details). Program evaluation has revealed that not only are clinicians satisfied with the training and support they receive (see Chapter 5), but they also demonstrate improved competencies, and patients report greater satisfaction with care (Chard et al., 2012; Karlin et al., 2013a,b; Walser et al., 2013).

Based on the successes of NICE and the VA, it is possible to develop a

process for conducting systematic reviews and creating guidelines and implementation materials for psychosocial interventions, as well as a process for evaluating the impact of these tools, by leveraging existing resources. The committee envisions a process that entails the procedures detailed below and, as with NICE, involves input from consumers, professional organizations, and clinicians at every step. The inclusion of consumers in guideline development groups is important, although challenging (Harding et al., 2011). In their review of consumer involvement in NICE’s guideline development, Harding and colleagues (2011) recommend a shared decision-making approach to consumer support: consumers may receive support from consumer organizations, and should be provided with “decision support aids” for grading and assessment purposes and given an opportunity to discuss with other stakeholders any of their concerns regarding the content of the proposed guidelines, with clear direction on how to initiate those discussions. This approach can be supported by participatory action research training as discussed in Chapter 2 (Graham et al., 2014; Scharlach et al., 2014).

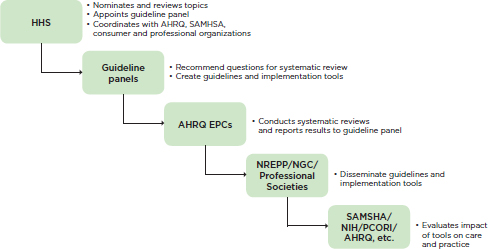

A potential direction for the United States is for the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), in partnership with professional and consumer organizations, to develop a coordinated process for conducting systematic reviews of the evidence for psychosocial interventions and creating guidelines and implementation materials in accordance with the IOM standards for guideline development. Professional and consumer organizations, which are in the best position to inform the review process, could work collaboratively with representation from multiple stakeholders, including consumers, researchers, professional societies and organizations, policy makers, health plans, purchasers, and clinicians. This body would recommend guideline topics, appoint guideline development panels (also including consumers, researchers, policy makers, health plans, purchasers, and clinicians), and develop procedures for evaluating the impact of the guidelines on practice and outcomes. When a topic for review was nominated, a comment period would be held so that consumers and clinicians could register interest in the topic. Once the body had recommended a topic for review and the guideline panel had been formed, the panel would identify the questions to be addressed by the systematic review and create guidelines based on the review. For topics on which systematic reviews and guidelines already exist, a panel would review these guidelines and recommend whether they should be disseminated or require update and/or revision.

AHRQ’s EPCs2 are in a good position to assist with the coordination of systematic reviews based on the questions provided by the guideline panels. EPCs are not governmental organizations but institutions. AHRQ currently awards the EPCs 5-year contracts for systematic reviews of existing research on the effectiveness, comparative effectiveness, and comparative harms of different health care interventions for publically nominated health care topics in accordance with the IOM recommendations for conducting high-quality systematic reviews (IOM, 2011). The topics encompass all areas of medicine, including mental health and substance use disorders. The EPCs would report the results of the systematic reviews of the evidence for psychosocial interventions to the guideline panels, which would then create practice guidelines accordingly.

HHS could work with SAMHSA’s NREPP (SAMHSA, 2015), AHRQ’s National Guideline Clearinghouse (NGC) (AHRQ, 2014), and professional societies and organizations to make guidelines and implementation tools publicly available. Both the NREPP and the NGC were created to coordinate a searchable database of evidence-based practices accessible to any stakeholder, and professional organizations such as the American Psychological Association produce practice guidelines and training materials for association members. Currently, the NREPP is charged specifically with coordinating best practices for mental health and substance use disorders. This organization has been helpful to many mental health policy makers in identifying best practices. At present, however, the NREPP does not use a systematic review process to identify best practices, and as a result, it sometimes labels interventions as evidence based when the evidence in fact is lacking (Hennessy and Green-Hennessy, 2011). If the systematic reviews were conducted by an entity with expertise in the review process (for instance, an EPC), and another entity were charged with coordinating the focus of and topics for the reviews, the NREPP could concentrate its efforts on dissemination of the practice guidelines and implementation tools resulting from the reviews.

Finally, HHS could establish a process for evaluating the impact of the guidelines resulting from the above process on practice and outcomes. In particular, funding agencies charged with evaluating the quality of care (e.g., AHRQ) and the effectiveness of treatment (e.g., the National Institute of Mental Health [NIMH] and the National Institute on Drug Abuse)

_____________

2 Current EPCs include Brown University, Duke University, ECRI Institute–Penn Medicine, Johns Hopkins University, Kaiser Permanente Research Affiliates, Mayo Clinic, Minnesota Evidence-based Practice Center, Pacific Northwest Evidence-based Practice Center–Oregon Health and Science University, RTI International–University of North Carolina, Southern California Evidence-based Practice Center–RAND Corporations, University of Alberta, University of Connecticut, and Vanderbilt University. http://www.ahrq.gov/research/findings/evidencebased-reports/centers/index.html (accessed June 21, 2015).

FIGURE 4-1 Proposed process for conducting systematic reviews and developing guidelines and implementation tools.

NOTE: AHRQ = Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; EPC = Evidence-Based Practice Center; HHS = U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; NGC = National Guideline Clearinghouse; NIH = National Institutes of Health; NREPP = National Registry of Evidence-based Programs and Practices; PCORI = Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute; SAMHSA = Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.

would be poised to fund studies of the impact of the guidelines on practice and outcomes. Ideally, funding would be made available for research and evaluation partnerships among researchers, health care organizations, and consumer groups. The entire proposed process described above is summarized in Figure 4-1.

WHAT PROCESS SHOULD BE USED FOR REVIEWING THE EVIDENCE?

The IOM standards for systematic reviews have been adopted globally, and are now employed in countries with a formal process for determining whether a psychosocial intervention is indicated for a given problem (Qaseem et al., 2012). They also are currently used for guideline development by professional organizations such as the American Psychiatric Association and the American Psychological Association (Hollon et al., 2014). Briefly, the process entails establishing a guideline panel to identify critical questions that guide the systematic review, and ensuring that consumers are represented throughout the process. As noted earlier, the review should be conducted by a group of separate and independent guideline developers.

This group collects information from a variety of sources; grades the quality of that information using two independent raters; and then presents the evidence to the guideline panel, which is responsible for developing recommendations based on the review.

The systematic review process is guided by the questions asked. Typically, reviews focus on determining the best assessment and treatment protocols for a given disorder. Reviews usually are guided by what are called PICOT questions: In (Population U), what is the effect of (Intervention W) compared with (Control X) on (Outcome Y) within (Time Z) (Fineout-Overholt et al., 2005)? Other questions to be addressed derive from the FDA. When the FDA approves a drug or device for marketing, the existing data must provide information on its effective dose range, safety, tolerability/side effects, and effectiveness (showing that the drug/device has an effect on the mechanism underlying the disease being treated and is at least as efficacious as existing treatments) (FDA, 2014).

Although the PICOT and FDA questions are important in determining the effectiveness of psychosocial interventions, they are not sufficient to ensure appropriate adoption of an intervention. Often, questions related to moderators that facilitate or obstruct an intervention’s success, such as intervention characteristics, required clinician skill level, systems needed to support intervention fidelity, and essential treatment elements, are not included in systematic reviews, yet their inclusion is necessary to ensure that the intervention and its elements are implemented appropriately by health plans, clinicians, and educators.

It is well known that interventions such as assertive community treatment and psychotherapies such as cognitive-behavioral therapy are complex and may not need to be implemented in their entirety to result in a positive outcome (Lyon et al., 2015; Mancini et al., 2009; Salyers et al., 2003). Beyond the PICOT and FDA regulations, then, important additional questions include the minimal effective dose of an intervention and the essential elements in the treatment package. As discussed in Chapter 3, instead of having to certify clinicians in several evidence-based interventions, a more economical approach may be to identify their elements and determine the effectiveness of those elements in treating target problems for different populations and settings (Chorpita et al., 2005, 2007). The review process also should address the acceptability of an intervention to consumers. For example, cognitive-behavioral therapy for depression is a well-established, evidence-based psychosocial intervention that many health plans already cover; however, it is an intervention with high consumer dropout early in treatment, and early dropout is associated with poorer outcomes (Bados et al., 2007; Schindler et al., 2013; Schnicker et al., 2013).

Reviews also should extract information on the practicalities of implementing psychosocial interventions and their elements. Some psychoso-

cial interventions have been designed for non-mental health professionals (Mynors-Wallis, 1996), while others have been studied across professional groups (Montgomery et al., 2010). Before investing in an intervention, health plans and health care organizations need information about the amount of training and ongoing supervision, basic skills, and environmental supports needed to ensure that clinicians can implement the intervention. Finally, information on the effectiveness of psychosocial interventions across settings is important. As an example, one large study of depression management in primary care found that the intervention resulted in better outcomes when delivered by experts by phone (remotely) than when delivered by local clinicians trained in it (Fortney et al., 2012). Such information helps health care organizations make decisions about the best ways to implement psychosocial interventions effectively.

In sum, systematic reviews for psychosocial interventions should address the following questions:

- Intervention efficacy—Is the intervention effective? How is its effectiveness defined and measured? Is the intervention safe? How do its safety and effectiveness compare with those of alternative interventions? What are the minimal effective dose and dose range of treatment (frequency, intensity of setting, and duration)? When should effects reasonably be seen (response to the intervention and remission as a result of the intervention), and when should alternative treatments be considered? What are the essential elements of the intervention?

- Intervention effectiveness—Is there evidence that the intervention has positive effects across demographic/socioeconomic/racial/cultural groups? How acceptable is the intervention to consumers?

- Implementation needs—What are the procedural steps involved in the intervention and intervention elements? What qualifications or demonstrated competencies should clinicians, paraprofessionals, or treatment teams have to provide the intervention and its elements effectively? What is the procedure for training the clinician or clinician team? What supports need to be in place to ensure that the intervention and its elements are delivered at a high-quality level and sustained over time? What is the expected number of hours needed in corrective feedback to minimize skill drift? Is supervision required? In what settings can the intervention be deployed? What is the relative cost of the intervention compared with no treatment or alternative treatments?

Grading the Evidence

Asking the right questions for a systematic review is only half the process; identifying the best information with which to answer those questions is just as important. After a guideline panel has determined which questions should be answered by the review, the reviewers must comb the research and grey literature for any information that could be helpful. Once that information has been identified, it is reviewed for its quality with respect to providing definitive answers to the review questions. This review involves grading the quality of the studies’ methods and the quality of the evidence generated overall from the existing body of evidence. A number of grading systems for a body of evidence exist, but the one with the most clarity is the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) system (Guyatt et al., 2008). The GRADE system ranks the evidence according to the following categories:

- Confidence recommendations: There are several RCTs with consistent results, or one large-scale, multisite clinical trial.

- Future research is likely to have an important impact on the confidence of the recommendations: Only one high-quality study or several studies with limitations exist.

- Further research is very likely to impact the confidence of the recommendations: Only one or more studies with limitations exist.

- Estimate of effect is uncertain: Only expert opinion without direct research evidence is available.

AHRQ adds another important category, called X, when it commissions reviews. This category entails determining whether there is sufficient evidence that the intervention is not harmful.

At issue here is that, as noted earlier, the RCT is considered the gold standard for study designs, and designs that deviate from the RCT are considered less useful in informing recommendations. Yet the RCT method is not appropriate for all questions, such as those concerning implementation and system needs. In some circumstances, moreover, RCTs are not feasible because of pragmatic considerations, such as the lack of a credible control condition or a population’s reluctance to engage in randomization, or because of ethical considerations when the only available control is no or poor treatment (Kong et al., 2009; Tol et al., 2008). Suppose the critical question being studied is the number of hours in corrective training needed by a new cognitive-behavioral therapy clinician to maintain fidelity. Unless the aim is to compare needed supervision hours with those for another intervention, the study need not be an RCT, but can be purely observational (Victora et al., 2004). Grading of the extant evidence for a psychosocial intervention,

then, should depend on the question being asked, the intervention type, the desired outcome, and the quality to which the methodology of the intervention was employed.

Further, data from field trials and observational studies can complement data from RCTs and mechanistic trials, yet there is little support for this type of research in the arena of psychosocial interventions. While pharmaceutical companies historically have had the resources to field test their interventions, psychosocial interventions often are developed in the field and in academia, rather than by large companies. Whereas agencies such as the National Institutes of Health have served as the primary funders of research evaluating psychosocial interventions, funds for field and observational studies have been constrained by budgetary limitations. More funding is needed to evaluate these interventions so that systematic reviews can be conducted comprehensively.

Data Sources When Evidence Is Insufficient

In the health care domain, there often is incomplete or insufficient evidence with which to determine the effects and processes of interventions. For many psychosocial interventions, compelling evidence supports their effect on symptoms and function in various populations; however, evidence may not be available on relative costs, needed clinician qualifications, or dose of treatment. As discussed above, the evidence for an intervention may be insufficient because funding for research has not been made available. There are three potential solutions when evidence is not readily available to support recommendations on psychosocial interventions: (1) the Distillation and Matching Model (DMM, also called the elements model) (Becker et al., 2015; Chorpita et al., 2007; Lindsey et al., 2014), (2) the Delphi method (Arce et al., 2014), and (3) registries.

The DMM was developed to overcome many problems related to the existence of multiple evidence-based interventions with overlapping elements and the push to have clinicians certified in more than one of these interventions (as described in Chapter 3). The method also was developed to address situations in which a psychosocial intervention is not available for a particular problem. The DMM entails carrying out a series of steps to identify and distill the common elements across existing evidence-based interventions, enabling the identification of best practices for use when no evidence-based treatment is available. The steps in the model are (1) perform a systematic review of all existing interventions, using criteria similar to the IOM recommendations; (2) identify treatment strategies (i.e., elements) within those interventions that are evidence based (e.g., activity scheduling in cognitive-behavioral therapy); (3) identify the elements that are present in at least three existing manuals; and (4) employ intraclass correlations as

a means of distilling the remaining, overlapping strategies into final shared elements (Chorpita and Daleiden, 2009). This approach has been applied to child mental health services in California and Hawaii, with positive mental health outcomes in children for as long 2 years posttreatment and with clinicians being able to maintain fidelity to treatment models (Chorpita et al., 2013; Palinkas et al., 2013). The method’s major limitation is that it needs additional study. An example of its use is presented in Box 4-1.

The Delphi method—a form of consensus building used traditionally for expert forecasting, such as predicting how the stock market will look based on economic challenges, is a consensus approach to making recommendations about best practices when insufficient evidence is available. The principle behind the method is that forecasts from structured groups of experts are more accurate than those from unstructured groups or from individual predictions. The process includes several steps, beginning with identification of a group of experts who are given, in the present context, questions about what they believe to be evidence-based psychosocial interventions for a particular problem. These experts rarely meet one another during the process. In fact, their identities are kept confidential to minimize the tendency for individuals to defer to those in authority. After a survey group has collected an initial set of responses, it compiles the responses into another survey. That survey is sent back to the experts for further comment, including why they remain out of consensus. The process ends after about four rounds when consensus is reached.

Chorpita and colleagues (2007) describe a case in which no evidence-based treatment protocols were available for a 7-year-old boy suffering from depression. Using the DMM approach, they identified interventions for depression for which there was evidence for consumers who matched most of the boy’s clinical characteristics. They identified interventions for adolescent depression and from them distilled three elements across manuals—psychoeducation about depression geared toward children, and behavioral activation and relaxation training. They did not include cognitive training because this element, although it often occurred in evidence-based therapies, required intellectual capacity that young children do not possess.

SOURCE: Chorpita et al., 2007.

Registries are another potential source of information when evidence is lacking. Registries are data systems developed for the purpose of collecting health-related information from special populations. Historically, registries have served as sources of information when no RCTs are available, for rare or low-base-rate illnesses (e.g., cystic fibrosis), and for illnesses with no cure (e.g., Alzheimer’s disease), and also have been useful in studying the course and treatment response of common illnesses (e.g., diabetes). All consumers with the illness are invited to participate, with no specified inclusion or exclusion criteria. These registries also collect data on any therapies used in any settings. Registries have been employed in evaluating outcomes for the study of issues ranging from the natural history of a disease, to the safety of drugs or devices, to the real-world effectiveness of evidence-based therapies and their modified versions. Box 4-2 outlines the common uses for registries.

Registries are common and widely used in various fields of medicine. As one example, the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation has a registry consisting of health outcomes and clinical characteristics for approximately 26,000 cystic fibrosis patients. This registry has produced important data that now inform treatments used to prolong the survival of these patients. Groups representing other fields of medicine that use registries to inform practice

BOX 4-2

Overview of Registry Purposes

- Determining the clinical effectiveness, cost-effectiveness, or comparative effectiveness of a test or treatment, including evaluating the acceptability of drugs, devices, or procedures for reimbursement.

- Measuring or monitoring the safety and harm of specific products and treatments, including comparative evaluation of safety and effectiveness.

- Measuring or improving the quality of care, including conducting programs to measure and/or improve the practice of medicine and/or public health.

- Assessing natural history, including estimating the magnitude of a problem, determining an underlying incidence or prevalence rate, examining trends of disease over time, conducting surveillance, assessing service delivery and identifying groups at high risk, documenting the types of patients served by a health care provider, and describing and estimating survival.

SOURCE: AHRQ, n.d.

are the Society for Thoracic Surgeons, the American College of Cardiology, and the American Society of Anesthesiologists. Both the Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health (HITECH) Act and the ACA support the creation of online registries to improve the quality and reduce the cost of behavioral health interventions, as do health plans, purchasers, hospitals, physician specialty societies, pharmaceutical companies, and patients. As an example, the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute’s (PCORI’s) PCORnet program3 has the aim of developing a large and nationally representative registry to conduct comparative effectiveness research.

These approaches to data synthesis when information on psychosocial interventions is not readily available are particularly helpful in identifying directions for future research. When faced with minimal information about the utility of psychosocial interventions in understudied settings and populations, the entity conducting systematic reviews could employ these models to identify candidate best practices and to generate hypotheses about candidate interventions, and could work with research funding agencies (e.g., NIMH, PCORI) to deploy the candidate best practices and study their impact and implementation.

HOW CAN TECHNOLOGY BE LEVERAGED?

The greatest challenge in conducting systematic reviews is the cost and time required to complete the review and guideline development process. A systematic review takes approximately 18 months to conduct, and requires a team of content experts, librarians who are experts in literature identification, reviewers (at least two) who read the literature and extract the information needed to grade the evidence, potentially a biostatistician to review data analysis, and a project leader to write the report (Lang and Teich, 2014). The scope of the review often is constrained by the cost; each question and subsequent recommendation requires its own, separate systematic review. Sometimes new information about treatments is published after the review has been completed, and as a result is not included in the guidelines.

To avoid the cost and timeliness problems inherent in systematic reviews, an entity charged with overseeing the reviews and their products could explore the potential for technology and clinical and research networks and learning environments to expedite the process and the development of updates to recommendations.

In the case of technology, there are many contemporary examples of the use of machine-learning technologies for reliable extraction of information for clinical purposes (D’Avolio et al., 2011; de Bruijn et al., 2011;

_____________

3 See http://www.pcornet.org (accessed June 18, 2015).

Li et al., 2013; Patrick et al., 2011; Tang et al., 2013; Xu et al., 2012). Machine learning refers to training computers to detect patterns in data using Bayesian statistical modeling and then to develop decision algorithms based on those patterns. One study has demonstrated that machine-learning technology not only reduces the workload of systematic reviewers but also results in more reliable data extraction than is obtained with manual review (Matwin et al., 2010). Another study employed natural-language processing techniques, preprocessing key terms from study abstracts to create a semantic vector model for prioritizing studies according to relevance to the review. The researchers found that this method reduced the number of publications that reviewers needed to evaluate, significantly reducing the time required to conduct reviews (Jonnalagadda and Petitti, 2013). The application of this technology to ongoing literature surveillance also could result in more timely updates to recommendations. To be clear, the committee is not suggesting that machine learning be used to replace the systematic review process, but rather to augment and streamline the process, as well as potentially lower associated costs.

The use of clinical and research networks and learning environments to collect data on outcomes for new interventions and their elements is another potential way to ensure that information on psychosocial interventions is contemporary. As an example, the Mental Health Research Network (MHRN), an NIMH-funded division of the HMO Research Network and Collaboratory, consists of 13 health system research centers across the United States that are charged with improving mental health care. It comprises research groups, special interest groups, and a large research-driven infrastructure for conducting large-scale clinical trials and field trials (MHRN, n.d.). The MHRN offers a unique opportunity to study innovations in psychosocial interventions, system- and setting-level challenges to implementation, and relative costs. HHS could partner with consortiums such as the MHRN to obtain contemporary information on psychosocial interventions, as well as to suggest areas for research.

CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS

Approaches applied in other areas of health care (as recommended in previous IOM reports) can be applied in compiling and synthesizing evidence to guide care for mental health and substance use disorders.

Recommendation 4-1. Expand and enhance processes for coordinating and conducting systematic reviews of psychosocial interventions and their elements. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, in partnership with professional and consumer organizations, should

expand and enhance existing efforts to support a coordinated process for conducting systematic reviews of psychosocial interventions and their elements based on the Institute of Medicine’s recommendations for conducting high-quality systematic reviews. Research is needed to expedite the systematic review process through the use of machine learning and natural-language processing technologies to search databases for new developments.

Recommendation 4-2. Develop a process for compiling and disseminating the results of systematic reviews along with guidelines and dissemination tools. With input from the process outlined in Recommendation 4-1, the National Registry of Evidence-based Programs and Practices (NREPP) and professional organizations should disseminate guidelines, implementation tools, and methods for evaluating the impact of guidelines on practice and patient outcomes. This process should be informed by the models developed by the National Institute for Health Care and Excellence (NICE) in the United Kingdom and the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, and should be faithful to the Institute of Medicine standards for creating guidelines.

Recommendation 4-3. Conduct research to expand the evidence base for the effectiveness of psychosocial interventions. The National Institutes of Health should coordinate research investments among federal, state, and private research funders, payers, and purchasers to develop and promote the adoption of evidence-based psychosocial interventions. This research should include

- randomized controlled trials to establish efficacy, complemented by other approaches encompassing field trials, observational studies, comparative effectiveness studies, data from learning environments and registries, and private-sector data;

- trials to establish the effectiveness of interventions and their elements in generalizable practice settings; and

- practice-based research networks that will provide “big data” to continuously inform the improvement and efficiency of interventions.

AHRQ (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality). 1996. Clinical practice guidelines archive. http://www.ahrq.gov/professionals/clinicians-providers/guidelines-recommendations/archive.html (accessed June 11, 2015).

_____. 2011. Therapies for children with autism spectrum disorders. Comparative effectiveness review no. 26. AHRQ publication no. 11-EHC029-EF. http://www.effectivehealthcare.ahrq.gov/ehc/products/106/656/CER26_Autism_Report_04-14-2011.pdf (accessed May 29, 2015).

_____. 2014. About National Guideline Clearinghouse. http://www.guideline.gov/about/index.aspx (accessed February 5, 2015).

_____. n.d. Registries for evaluating patient outcomes: A user’s guide. http://effectivehealthcare.ahrq.gov/index.cfm/search-for-guides-reviews-and-reports/?productid=12&pageaction=displayproduct (accessed June 18, 2015).

Arce, J. M., L. Hernando, A. Ortiz, M. Díaz, M. Polo, M. Lombardo, and A. Robles. 2014. Designing a method to assess and improve the quality of healthcare in Nephrology by means of the Delphi technique. Nefrologia: Publicacion Oficial de la Sociedad Espanola Nefrologia 34(2):158-174.

Bados, A., G. Balaguer, and C. Saldana. 2007. The efficacy of cognitive-behavioral therapy and the problem of drop-out. Journal of Clinical Psychology 63(6):585-592.

Barry, C. L., J. P. Weiner, K. Lemke, and S. H. Busch. 2012. Risk adjustment in health insurance exchanges for individuals with mental illness. American Journal of Psychiatry 169(7):704-709.

Becker, K. D., B. R. Lee, E. L. Daleiden, M. Lindsey, N. E. Brandt, and B. F. Chorpita. 2015. The common elements of engagement in children’s mental health services: Which elements for which outcomes? Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology: The Official Journal for the Society of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, American Psychological Association, Division 53 44(1):30-43.

Cairns, R., J. Evans, and M. Prince. 2004. The impact of NICE guidelines on the diagnosis and treatment of Alzheimer’s disease among general medical hospital inpatients. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 19(8):800-802.

Chard, K. M., E. G. Ricksecker, E. T. Healy, B. E. Karlin, and P. A. Resick. 2012. Dissemination and experience with cognitive processing therapy. Journal of Rehabilitation Research and Development 49(5):667-678.

Chorpita, B. F., and E. L. Daleiden. 2009. Mapping evidence-based treatments for children and adolescents: Application of the distillation and matching model to 615 treatments from 322 randomized trials. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 77(3):566-579.

Chorpita, B. F., E. L. Daleiden, and J. R. Weisz. 2005. Identifying and selecting the common elements of evidence-based interventions: A distillation and matching model. Mental Health Services Research 7(1):5-20.

Chorpita, B. F., K. D. Becker, and E. L. Daleiden. 2007. Understanding the common elements of evidence-based practice: Misconceptions and clinical examples. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 46(5):647-652.

Chorpita, B. F., J. R. Weisz, E. L. Daleiden, S. K. Schoenwald, L. A. Palinkas, J. Miranda, C. K. Higa-McMillan, B. J. Nakamura, A. A. Austin, C. F. Borntrager, A. Ward, K. C. Wells, and R. D. Gibbons. 2013. Long-term outcomes for the Child STEPs randomized effectiveness trial: A comparison of modular and standard treatment designs with usual care. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 81(6):999-1009.

Clark, D. M. 2011. Implementing NICE guidelines for the psychological treatment of depression and anxiety disorders: The IAPT experience. International Review of Psychiatry 23(4):318-327.

D’Avolio, L. W., T. M. Nguyen, S. Goryachev, and L. D. Fiore. 2011. Automated concept-level information extraction to reduce the need for custom software and rules development. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association 18(5):607-613.

de Bruijn, B., C. Cherry, S. Kiritchenko, J. Martin, and X. Zhu. 2011. Machine-learned solutions for three stages of clinical information extraction: The state of the art at i2b2 2010. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association 18(5):557-562.

Decker, S. L., D. Kostova, G. M. Kenney, and S. K. Long. 2013. Health status, risk factors, and medical conditions among persons enrolled in Medicaid vs. uninsured low-income adults potentially eligible for Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act. Journal of the American Medical Association 309(24):2579-2586.

FDA (U.S. Food and Drug Administration). 2014. FDA fundamentals. http://www.fda.gov/AboutFDA/Transparency/Basics/ucm192695.htm (accessed February 5, 2015).

Fineout-Overholt, E., S. Hofstetter, L. Shell, and L. Johnston. 2005. Teaching EBP: Getting to the gold: How to search for the best evidence. Worldviews on Evidence-Based Nursing 2(4):207-211.

Fortney, J., M. Enderle, S. McDougall, J. Clothier, J. Otero, L. Altman, and G. Curran. 2012. Implementation outcomes of evidence-based quality improvement for depression in VA community-based outpatient clinics. Implementation Science: IS 7:30.

Graham, T., D. Rose, J. Murray, M. Ashworth, and A. Tylee. 2014. User-generated quality standards for youth mental health in primary care: A participatory research design using mixed methods. BMJ Quality & Safety Online 1-10.

Guyatt, G. H., A. D. Oxman, G. E. Vist, R. Kunz, Y. Falck-Ytter, and H. J. Schünemann. 2008. Grade: What is “quality of evidence” and why is it important to clinicians? British Medical Journal 336(7651):995-998.

Harding, K. J., A. J. Rush, M. Arbuckle, M. H. Trivedi, and H. A. Pincus. 2011. Measurement-based care in psychiatric practice: A policy framework for implementation. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 72(8):1136-1143.

Hennessy, K. D., and S. Green-Hennessy. 2011. A review of mental health interventions in SAMHSA’s National Registry of Evidence-based Programs and Practices. Psychiatric Services 62(3):303-305.

Hollon, S. D., P. A. Arean, M. G. Craske, K. A. Crawford, D. R. Kivlahan, J. J. Magnavita, T. H. Ollendick, T. L. Sexton, B. Spring, L. F. Bufka, D. I. Galper, and H. Kurtzman. 2014. Development of clinical practice guidelines. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology 10:213-241.

IOM (Institute of Medicine). 2011. Clinical practice guidelines we can trust. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Jonnalagadda, S., and D. Petitti. 2013. A new iterative method to reduce workload in systematic review process. International Journal of Computational Biology and Drug Design 6(1-2):5-17.

Karlin, B. E., and G. Cross. 2014a. Enhancing access, fidelity, and outcomes in the national dissemination of evidence-based psychotherapies. The American Psychologist 69(7):709-711.

_____. 2014b. From the laboratory to the therapy room: National dissemination and implementation of evidence-based psychotherapies in the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs health care system. The American Psychologist 69(1):19-33.

Karlin, B. E., R. D. Walser, J. Yesavage, A. Zhang, M. Trockel, and C. B. Taylor. 2013a. Effectiveness of acceptance and commitment therapy for depression: Comparison among older and younger veterans. Aging & Mental Health 17(5):555-563.

Karlin, B. E., M. Trockel, C. B. Taylor, J. Gimeno, and R. Manber. 2013b. National dissemination of cognitive-behavioral therapy for insomnia in veterans: Therapist- and patient-level outcomes. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 81(5):912-917.

Kong, E. H., L. K. Evans, and J. P. Guevara. 2009. Nonpharmacological intervention for agitation in dementia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Aging & Mental Health 13(4):512-520.

Lang, L. A., and S. T. Teich. 2014. A critical appraisal of the systematic review process: Systematic reviews of zirconia single crowns. The Journal of Prosthetic Dentistry 111(6): 476-484.

Li, Q., H. Zhai, L. Deleger, T. Lingren, M. Kaiser, L. Stoutenborough, and I. Solti. 2013. A sequence labeling approach to link medications and their attributes in clinical notes and clinical trial announcements for information extraction. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association 20(5):915-921.

Lindsey, M. A., N. E. Brandt, K. D. Becker, B. R. Lee, R. P. Barth, E. L. Daleiden, and B. F. Chorpita. 2014. Identifying the common elements of treatment engagement interventions in children’s mental health services. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review 17(3):283-298.

London, P., and G. L. Klerman. 1982. Evaluating psychotherapy. American Journal of Psychiatry 139(6):709-717.

Lyon, A. R., S. Dorsey, M. Pullmann, J. Silbaugh-Cowdin, and L. Berliner. 2015. Clinician use of standardized assessments following a common elements psychotherapy training and consultation program. Administration and Policy in Mental Health 42(1):47-60.

Mancini, A. D., L. L. Moser, R. Whitley, G. J. McHugo, G. R. Bond, M. T. Finnerty, and B. J. Burns. 2009. Assertive community treatment: Facilitators and barriers to implementation in routine mental health settings. Psychiatric Services 60(2):189-195.

Matwin, S., A. Kouznetsov, D. Inkpen, O. Frunza, and P. O’Blenis. 2010. A new algorithm for reducing the workload of experts in performing systematic reviews. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association 17(4):446-453.

MHRN (Mental Health Research Network). n.d. About. https://sites.google.com/a/mhresearchnetwork.org/mhrn/home/about-us (accessed February 6, 2015).

Montgomery, E. C., M. E. Kunik, N. Wilson, M. A. Stanley, and B. Weiss. 2010. Can paraprofessionals deliver cognitive-behavioral therapy to treat anxiety and depressive symptoms? Bulletin of the Menninger Clinic 74(1):45-62.

Mynors-Wallis, L. 1996. Problem-solving treatment: Evidence for effectiveness and feasibility in primary care. International Journal of Psychiatry in Medicine 26(3):249-262.

NAC (National Autism Center). 2009. National standards report: Phase 1. http://dlr.sd.gov/autism/documents/nac_standards_report_2009.pdf (accessed February 21, 2015).

NICE (National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence). 2011. Common mental health disorders: Identification and pathways to care. Leicester, UK: British Psychological Society.

_____. 2014. Developing NICE guidelines: The manual. https://www.nice.org.uk/article/pmg20/chapter/1-Introduction-and-overview (accessed February 5, 2014).

_____. 2015. Guidance list. http://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/published?type=Guidelines (accessed June 11, 2015).

Palinkas, L. A., J. R. Weisz, B. F. Chorpita, B. Levine, A. F. Garland, K. E. Hoagwood, and J. Landsverk. 2013. Continued use of evidence-based treatments after a randomized controlled effectiveness trial: A qualitative study. Psychiatric Services 64(11):1110-1118.

Patel, V. L., J. F. Arocha, M. Diermeier, R. A. Greenes, and E. H. Shortliffe. 2001. Methods of cognitive analysis to support the design and evaluation of biomedical systems: The case of clinical practice guidelines. Journal of Biomedical Informatics 34(1):52-66.

Patrick, J. D., D. H. Nguyen, Y. Wang, and M. Li. 2011. A knowledge discovery and reuse pipeline for information extraction in clinical notes. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association 18(5):574-579.

Payne, H., N. Clarke, R. Huddart, C. Parker, J. Troup, and J. Graham. 2013. Nasty or nice? Findings from a U.K. survey to evaluate the impact of the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) clinical guidelines on the management of prostate cancer. Clinical Oncology 25(3):178-189.

Pilling, S., and K. Price. 2006. Developing and implementing clinical guidelines: Lessons from the NICE schizophrenia guideline. Epidemiologia e Psichiatria Sociale 15(2):109-116.

Qaseem, A., F. Forland, F. Macbeth, G. Ollenschläger, S. Phillips, and P. van der Wees. 2012. Guidelines international network: Toward international standards for clinical practice guidelines. Annals of Internal Medicine 156(7):525-531.

Salyers, M. P., G. R. Bond, G. B. Teague, J. F. Cox, M. E. Smith, M. L. Hicks, and J. I. Koop. 2003. Is it ACT yet? Real-world examples of evaluating the degree of implementation for assertive community treatment. Journal of Behavioral Health Services & Research 30(3):304-320.

SAMHSA (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration). 2015. About SAMHSA’s National Registry of Evidence-based Programs and Practices. http://www.nrepp.samhsa.gov/AboutNREPP.aspx (accessed February 5, 2015).

Scharlach, A. E., C. L. Graham, and C. Berridge. 2014. An integrated model of co-ordinated community-based care. Gerontologist doi:10.1093/geront/gnu075.

Schindler, A., W. Hiller, and M. Witthoft. 2013. What predicts outcome, response, and drop-out in CBT of depressive adults? A naturalistic study. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy 41(3):365-370.

Schnicker, K., W. Hiller, and T. Legenbauer. 2013. Drop-out and treatment outcome of outpatient cognitive-behavioral therapy for anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa. Comprehensive Psychiatry 54(7):812-823.

Tang, B., Y. Wu, M. Jiang, Y. Chen, J. C. Denny, and H. Xu. 2013. A hybrid system for temporal information extraction from clinical text. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association 20(5):828-835.

Tol, W. A., I. H. Komproe, D. Susanty, M. J. Jordans, R. D. Macy, and J. T. De Jong. 2008. School-based mental health intervention for children affected by political violence in Indonesia: A cluster randomized trial. Journal of the American Medical Association 300(6):655-662.

VA (U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs). 2015. Health Services Research and Development: Evidence-Based Synthesis Program. http://www.hsrd.research.va.gov/publications/esp (accessed February 5, 2015).

Victora, C. G., J. P. Habicht, and J. Bryce. 2004. Evidence-based public health: Moving beyond randomized trials. American Journal of Public Health 94(3):400-405.

Vyawahare, B., N. Hallas, M. Brookes, R. S. Taylor, and S. Eldabe. 2014. Impact of the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidance on medical technology uptake: Analysis of the uptake of spinal cord stimulation in England 2008-2012. BMJ Open 4(1):e004182.

Walser, R. D., B. E. Karlin, M. Trockel, B. Mazina, and C. Barr Taylor. 2013. Training in and implementation of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy for depression in the Veterans Health Administration: Therapist and patient outcomes. Behaviour Research and Therapy 51(9):555-563.

Wen, H., J. R. Cummings, J. M. Hockenberry, L. M. Gaydos, and B. G. Druss. 2013. State parity laws and access to treatment for substance use disorder in the United States: Implications for federal parity legislation. JAMA Psychiatry 70(12):1355-1362.

Xu, Y., K. Hong, J. Tsujii, and E. I. Chang. 2012. Feature engineering combined with machine learning and rule-based methods for structured information extraction from narrative clinical discharge summaries. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association 19(5):824-832.

This page intentionally left blank.