Interventions in the Illicit Tobacco Market: Policy and Regulatory Options

As discussed above, a variety of factors, both in the United States and elsewhere, give rise to illicit tobacco markets. Many countries have implemented policies aimed at reducing illicit tobacco trade, and their experiences provide lessons that can inform domestic intervention strategies. The World Health Organization’s (WHO) Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC) and its illicit trade protocol distill many of the lessons derived from international experiences to date and provide a roadmap for comprehensive and integrated anti-contraband policy on the national, transnational, and global levels: see Box 5-1.

Drawing on these international experiences and on what is known about the U.S. illicit tobacco trade, this and the next two chapters identify a range of possible interventions to reduce the size of the U.S. illicit tobacco market. These chapters address a specific charge in the committee’s statement of task. This chapter covers control of the supply chain, tax harmonization, and public education campaigns; Chapter 6 covers law enforcement; and Chapter 7 presents case studies of comprehensive intervention efforts in three countries and the European Union (EU).

As described in Chapter 2, there are a number of points along the supply chain where tobacco and tobacco products can be diverted to the illicit market. Bootlegging, large-scale smuggling, illicit whites, and illegal manufacturing (including counterfeiting) are each linked to diversion at a particular phase in the legal supply chain of cigarettes (see Figure 2-1 in

BOX 5-1

WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control, Protocol to Eliminate Illicit Trade in Tobacco Products

Article 15 of the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC) “recognize[s] that the elimination of all forms of illicit trade in tobacco products . . . and the development and implementation of related national law, in addition to subregional, regional, and global agreements, are essential components of tobacco control” (World Health Organization, 2003, p. 13). The Protocol to Eliminate Illicit Trade in Tobacco Products (”protocol”), derived from Article 15, was adopted by the fifth session of the conference of parties of the WHO FCTC in November 2012. The protocol was opened for signature and ratification on January 10, 2013, and remained open until January 9, 2014. It was signed by 53 countries (though not the United States) and the European Union. However, for the protocol to enter into force, it needs both signature and ratification by 40 parties, and only six countries have ratified it to date.

Parties to the protocol are obliged to implement a number of domestic measures to control the supply chain, including

- licensing (Article 6)

- due diligence (Article 7)

- tracking and tracing (Article 8)

- recordkeeping (Article 9)

- security and preventive measures (Article 10)

- sale by Internet (Article 11)

- free zones and international transit (Article 12)

- dutyfree sales (Article 13)

In addition to supplychain controls, the protocol calls for signatories to establish a number of activities as “unlawful,” such as illegal production and tobacco product smuggling. These unlawful activities should be subject to “effective, proportionate, and dissuasive sanctions” (World Health Organization, 2013a, p. 20). The protocol establishes a precedent for international cooperation not only to

Chapter 2). Opportunities for diversion exist at all the stages in the supply chain: preproduction, production, taxation/in-transit, wholesale, and retail. Interventions to control and monitor the participants at each stage in the supply chain—such as licensing, digital tax stamps, and track-and-trace systems—and have, when coupled with enhanced enforcement of such requirements, have been shown to be useful in reducing these diversions and limiting the supply of tobacco products in the illicit market.

investigate illicit trade, but also to cooperate through information sharing, technical assistance, and financing.

The protocol is “essentially a customs and law enforcement treaty born into a health institution” (Liberman, 2012, p. 2). As such, the necessary expertise needed to implement the protocol (i.e., expertise regarding customs and supply chain control, criminal law and law enforcement, and information technology in the context of global information sharing) is absent within the WHO, and it has been difficult to procure the necessary funding to build additional internal expertise. In addition, there is an inherent tension between the FCTC and the protocol: the FCTC views the tobacco industry cautiously and urges parties to establish measures to limit their interactions (FCTC Article 5.3); whereas the international agencies who have the expertise and capacity to facilitate the implementation of the protocol view the tobacco industry as yet another private stakeholder with whom close cooperation can be necessary and useful (see Chapter 1 for a discussion of INTERPOL’s relationship with the tobacco industry).

Due in part to these challenges, the protocol has only been ratified by six countries. Without ratification and the enactment of corresponding domestic implementing legislation, as is needed for similar international treaties and conventions, the protocol is essentially “toothless.” This situation echoes what is also found in other spheres, such as protocols against money laundering: Halliday and colleagues (2014), for example, refer to the creation of “Potemkin villages” of apparent compliance with systems and institutions.

Despite these limitations, the FCTC Illicit Trade Protocol remains an important guiding document for controlling the illicit tobacco trade. As international relations scholars have noted, treaty norms often represent longterm goals that are set higher than many participating countries can or want to comply with immediately or within the foreseeable future (e.g., Neumayer, 2005). The FCTC itself was viewed as an aspirational document, and in recent years it has contributed to considerable strengthening of tobacco control policies, particularly in low and middleincome countries. Thus, though the protocol has yet to be adopted on a wide scale, it can be viewed as an aspirational document, codifying principles of tobacco control and outlining a future path for international health cooperation.

Licensing

Governments can require participants throughout the supply chain—including tobacco growers, manufacturers, distributors, wholesalers, and retailers—to be licensed, imposing obligations or restrictions on them.1 Governments can mandate that failure to comply with such obligations or

_______________

1 Article 6 of the FCTC Protocol calls for parties to require licensing of any person who produces tobacco manufacturing equipment and of persons who commercially transport tobacco manufacturing equipment, potentially affecting the ease with which such equipment is currently acquired.

restrictions will result in administrative, civil, or criminal penalties, depending on the location and severity of the infraction. Other control measures, such as requirements for record-keeping and limits on quantities of tobacco products sold, can regulate the supply chain without explicitly requiring formal licensing.

As discussed in Chapter 2, the preproduction stage of the supply chain—that is, the cultivation of tobacco and the production of other materials necessary for the manufacture of cigarettes, such as filter tips and cigarette papers (see Box 2-1 in Chapter 2)—is not subject to licensing or other regulatory oversight in any U.S. jurisdiction, which is also the case in many other countries. Australia is an exception as one of the few countries to regulate cigarette production at the preproduction stage: see Box 5-2. Some of the regulations at this stage may prove challenging to implement and enforce because of the abundance and availability of many of the materials necessary for cigarette production (i.e., cigarette manufacturing machinery and other inputs)—in contrast to, for example, some methamphetamine precursors. One significant exception may be acetate tow, a fiber made from wood pulp that is used in filters to control smoke flow.2 Despite the absence of preproduction controls in the United States, however, neither the illegal production of cigarettes by unlicensed manufacturers nor the production of counterfeit cigarettes appears to be prevalent in the country.

This absence of this problem in the United States may be due in part to the licensing requirements at the production and taxation/in-transit stages of the supply chain. Manufacturers, importers, and export warehouse proprietors of tobacco products or cigarette papers or tubes are required to obtain a license from the Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau of the U.S. Department of the Treasury prior to engaging in business operations.3 Violations of licensing requirements including underreporting production, operating without a license, and evading taxes are punishable by fines of not more than $10,000 or imprisonment of not more than 5 years, or both. All products, machinery, and property used to engage in the manufacture, import, or export of tobacco products or cigarette papers or tubes without

_______________

2 Acetate tow is produced by a limited pool of companies and has few substitutes, and the tracking and tracing of acetate tow also could be facilitated by the fact that it has a unique code in the harmonized tariff schedules of Brazil, Canada, China, the European Union, and the United States. Restricting and regulating the availability of acetate tow could especially disrupt counterfeit production, which requires that the products look and feel like major brand cigarettes. Restrictions could be imposed from outside the country where the illicit cigarettes are produced, which would be especially advantageous when local cooperation is absent (Framework Convention Alliance, 2010; ICIS Chemical Business, 2010; Joossens, 2011).

3 The permit may be denied for an applicant who has been convicted of tobacco-related felonies or who is deemed not likely to comply with regulations on the basis of previous or ongoing legal proceedings for tobacco-related felonies.

BOX 5-2

Preproduction Regulation in Australia

Historically, the domestic Australian tobacco market has been federally regulated and subsidized. Beginning in 1965, the Australian government required manufacturers to include a certain percentage of Australiangrown tobacco leaf in their products and allocated supply quotas (a license to grow tobacco) to local farmers. In the mid1990s, finecut tobacco known as “chopchop” entered the domestic Australian market illicitly, due in part to policies that deregulated the domestic market and opened it to tobacco leaf from abroad. As a result, chopchop became extremely profitable; tobacco farmers could earn up to Aus $10,000 per bale of tobacco on the illicit market compared to Aus $800 on the legal market (Scollo and Winstanley, 2012).*

Even though licensing requirements place restrictions on the supply of tobacco leaf entering the market, the Australian example demonstrates that licensing requirements have certain limitations. They must be enforced, and even when enforcement exists, prosecution of violators may be difficult. For example, when the Australian Tax Office, responsible for monitoring licensed tobacco growers, seized illicit chopchop, it had difficulty proving that the tobacco leaf was grown and diverted to the black market from a particular farm, limiting its ability to prosecute license violations (Australian National Audit Office, 2006; Sweeting et al., 2009).

Despite these limitations, the regulations in Australia appear to have made an impact on the country’s illicit tobacco market. Data from the National Drug Strategy Household Survey demonstrate that the majority of Australian smokers who have ever used illicit tobacco no longer use it, and estimates indicate that the size of the Australian illicit tobacco market in 2010 was minimal, between 2 and 3 percent of the country’s total tobacco market (Scollo and Winstanley, 2012).

_____________

*Commercial tobacco growing no longer exists in Australia. The Tobacco Marketing Act of 1965, which established the Tobacco Industry Stabilisation Plan and the Local Leaf Content Boards, was abolished in 1997. At that time, the government provided financial incentives for tobacco growers to leave the market. A federalgovernment and industryfunded buyout of the leafgrowing industry was agreed to in 2006 (Scollo and Winstanley, 2012).

a license are subject to forfeiture.4 Anyone who sells, re-imports, or receives tobacco products or cigarette papers and tubes designated for export, and anyone who aids or abets such activities, must pay the liable taxes due and be fined the greater of $1,000 or five times the imposed tax. All products

_______________

4 U.S. Internal Revenue Code §5701, Title 26, Chapter 52: Tobacco products and cigarette papers and tubes. Available: http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/USCODE-2011-title26/pdf/USCODE-2011-title26-subtitleE-chap52.pdf [June 2014].

seized and all vessels, vehicles, and aircraft used in attempts to reimport are subject to forfeiture.

As discussed in Chapter 2, the illicit tobacco market in the United States does not appear to be supplied by tobacco products that have evaded federal taxes through export-reimport schemes, and there is no evidence to suggest that underreporting of production by licensed U.S. manufacturers is widespread. Cases of illegal production of cigarettes by unlicensed manufacturers have not come to the attention of the committee, nor does the production of counterfeit cigarettes appear to be prevalent in the United States. The licensing requirements and penalties for violations at the production and taxation/in-transit phases of the supply chain, when enforced, may significantly impede such procurement schemes.

Supply chain controls can also be imposed at the wholesale and retail stages. These controls could be implemented to prevent diversion through tax-exempt distribution to noneligible consumers (e.g., state tax-exempt sales on military bases to nonmilitary people or tax-exempt sales on Native American reservations to non-Native Americans) or to limit opportunities for bootlegging and smurfing schemes. The evidence from Canada demonstrates how controls at the provincial level may affect tax-exempt distribution to noneligible purchasers (see Chapter 7).

In the United States, there are no federal licensing requirements at the wholesale stage, but all 50 states and the District of Columbia require tobacco wholesalers to be licensed. However, the requirements for obtaining a wholesaler license and the severity of restrictions placed on licensees vary and are not necessarily prohibitive. In a presentation to the committee, for example, a representative from the Northern Virginia Cigarette Tax Board indicated that in order to obtain a wholesaler license in Virginia, an applicant needs only a phone number and address; no fee is required. The representative also suggested that diversion at the wholesale level appears to be common in Virginia, where smugglers obtain cigarettes from wholesale box stores like Sam’s Club and Costco without paying the state sales tax. In contrast, California requires a $1,000 application fee for a wholesaler for each licensed location; licenses must be renewed annually, and there is a fee of $1,000 for each renewal. California wholesalers are subject to additional restrictions on purchases, sales, and record-keeping that carry enforcement and criminal penalties (California State Board of Equalization, n.d.).

Requiring tobacco-retailer licensing can be a useful tool for administering tobacco tax and point-of-sale laws and also can be used to help jurisdictions control the location and concentration of tobacco retailers (McLaughlin, 2010). In the United States, however, federal controls at the retail stage of the supply chain are limited. Although the Preventing All Cigarette Trafficking Act of 2009 (PACT Act) reduces the availability of

BOX 5-3

U.S. Internet Cigarette Sales

Most Internet cigarette sales are completed without payment of proper state and local taxes and violate laws regarding sales to minors. In 2007, 78 percent of Internet cigarette venders advertised that they sold cigarettes “tax free” (Ribisl et al., 2007). New York State alone lost between $106 and $122 million in tax revenues in 2004 from Internet sales (Davis et al., 2006).

In light of these sales, in 2005 the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms, and Explosives (ATF), along with a number of state attorneys general, reached an agreement with the major credit card companies and PayPal to ban the processing of payments from online cigarette sellers. That same year the major delivery services, including UPS and FedEx, entered into a similar agreement to stop delivery of cigarettes to consumers. These early agreements are believed to have curtailed Internet cigarette sales to some degree: notably, Ribisl and colleagues (2011) found that online traffic to Internet cigarette venders declined drastically after the agreements went into effect. However, the agreements contained notable loopholes that allowed cigarettes to be purchased online with personal checks, money orders, and electronic checks, to be delivered by the U.S. Postal Service (USPS), and to be sold without age verification.

Consequently, in 2009 the Prevent All Cigarette Trafficking Act (PACT Act) was adopted to further regulate Internet cigarette sales and address these gaps (see Box 1-2 in Chapter 1). It requires that all state tobacco taxes be paid prior to delivering any cigarettes or smokeless tobacco to buyers in that state, makes mailing cigarettes or smokeless tobacco products through the USPS illegal, establishes a federal list (maintained by ATF) of online sellers operating in violation of the law, and prohibits common carriers and other delivery services from delivering any packages for sellers that appear on the “Noncompliant Delivery Sellers List.” Lawful Internet sellers are able to transport cigarettes or smokeless tobacco to consumers through messenger services.

Because Internet cigarette sales are a major part of many Native American tribes’ economies, 140 Native Americanowned cigarette retailers sued to prevent the enforcement of the law. After 3 years of litigation, the suit was dismissed, and all provisions of the PACT Act became enforceable in June 2013. Of course, the law will only be as effective as its enforcement; given the relative newness of the PACT Act, there are as yet no comprehensive evaluations of it.

tax-evaded, low-cost cigarettes over the Internet, there is no federal licensing requirement for the sale of tobacco products: see Box 5-3.

Some states and localities do license retailers, although their requirements vary greatly. For example, the California Cigarette and Tobacco Products Licensing Act of 2003 (Licensing Act) requires retailers to obtain a license from the Board of Equalization (Tang et al., 2009).5 The Licens-

_______________

5 The California Licensing Act also requires manufacturers, importers, wholesalers, and distributors to obtain a license (McLaughlin, 2010).

ing Act provides for civil and criminal penalties that range from monetary fines to license suspension or revocation, and it authorizes the board to seize cigarettes or other tobacco products purchased in violation of the Licensing Act or found to be untaxed (Tang et al., 2009, p. 164; Horton, 2010, p. 3). Similarly, the New York State licensing law requires retailers to acquire a certificate of registration in order to sell cigarettes or other tobacco products (McLaughlin, 2010). Notably, however, Virginia—a main source state for illicit cigarettes—does not require retailers to have a license to sell cigarettes.

The absence of consistent state regulations and comprehensive federal controls may contribute to the increased diversion that has been seen at the wholesale and retail phases of the supply chain in the United States. Licensing of wholesalers and retailers can affect the flow of illicit cigarettes into the market. The Institute of Medicine (2007) noted the importance of controlling the tobacco retail sales environment and recommended that all states license retail sales outlets that sell tobacco products. Licensing retailers may be particularly important in low-tax jurisdictions, where diversion generally occurs. When diversion occurs at the retail phase, state excise taxes have already been paid, so it is low-tax jurisdictions that are most susceptible to illicit sales at this phase of the supply chain. However, those jurisdictions may have little incentive to reduce diversion because they stand to benefit from increased revenues from higher-volume cigarette sales. Conversely, diversion that occurs at the wholesale phase generally occurs prior to sales taxes being paid. In this case, both low- and high-tax jurisdictions should have incentives to adequately control the flow of cigarettes diverted at this stage.

Tax Stamps

Many governments require tax stamps (banderoles) to be applied to tobacco products in order to identify products on which excise or other taxes have been paid and for helping to ensure that products taxed in one jurisdiction are not being resold in another jurisdiction without payment of appropriate taxes. Typically, tax stamps are sold to and applied by either a producer or distributor who pays all applicable taxes, with some governments providing a small payment or rebate for the application of the tax stamp. The absence of a tax stamp in a jurisdiction that requires one is helpful for easily identifying illicit tobacco products.

Requirements for tax stamps vary widely in the United States and around the world. In the United States, nearly all states require tax stamps on cigarettes; the only states that do not require cigarette tax stamps are North Carolina, North Dakota, and South Carolina. Similarly, local governments with significant cigarette excise taxes, including Chicago and

Cook County, Illinois, and New York City require tax stamps. In contrast, almost no states require tax stamps on other tobacco products. Internationally, some countries require tax stamps on all tobacco products sold in that country; others forgo tax stamps entirely; and others require stamps on some, but not all, tobacco products. For example, in Vietnam, tax stamps are required on all cigarettes domestically manufactured by legally established companies.6

Some jurisdictions require different stamps on the same tobacco products. For example, in Ontario, Canada, all tax-exempt products must be sold with black-stock markings indicating that federal excise but not provincial taxes have been paid in order to easily identify tax-exempt products sold from Native American reserves (Sweeting et al., 2009). Serbia’s tax stamps vary based on whether brands are domestic, locally produced brands, international brands produced under license, or imported brands. Similarly, Arizona requires different colored tax stamps for cigarettes sold by Native American tribes, with the color of the stamp varying for cigarettes sold on reservations to reservation residents, sold on reservations to non-tribal members, and sold outside the reservation.

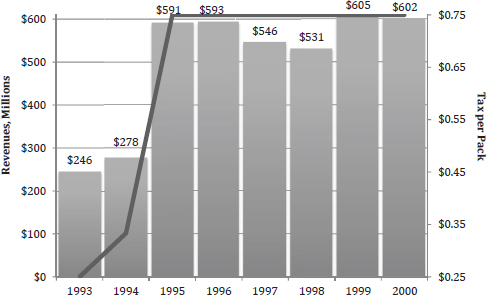

The utility of tax stamps in increasing tax compliance and identifying illicit tobacco is ably illustrated by the experience in Michigan in the mid-1990s. On May 1, 1994, Michigan raised its cigarette excise tax from 25 cents per pack to 75 cents per pack, which was then the single largest increase ever enacted for a state. At the time, Michigan did not require tax stamps on cigarettes sold in the state. Soon after the tax increase, North Carolina repealed its requirement that stamps be applied to cigarettes sold there, and South Carolina subsequently did the same. Those two states had among the lowest cigarette excise taxes in the country at the time, 5 cents per pack in North Carolina and 7 cents per pack in South Carolina, amounting to roughly a 70-cent difference between the price of cigarettes sold in Michigan and the two other states. Cigarettes were soon being bootlegged from the Carolinas to Michigan, and the lack of a tax stamp in Michigan hindered the ability of state tax authorities to assess compliance and to enforce the state’s relatively high cigarette tax. Cigarette excise tax revenues in Michigan increased sharply immediately following the tax increase, but they eroded quickly as illicit cigarettes became more available. In 1998, Michigan passed new legislation requiring a tax stamp on all cigarettes sold in the state. In the year following that requirement, Michigan’s cigarette tax revenues increased by 14 percent despite no increase in the state excise tax: see Figure 5-1. At the same time, cigarette sales fell by about 9 percent in North Carolina and by more than 13 percent in South

_______________

6 Prime Minister’s Decision No. 175/1999/QĐ-TTg, see http://policy.mofcom.gov.cn/english/flaw!fetch.action?id=d6b5034b-6ab1-4bf6-91e1-ecca60e19570 [January 2015].

FIGURE 5-1 Cigarette tax revenues in Michigan, 1990-2000.

SOURCE: Data from Orzechowski and Walker (2014).

Carolina, almost certainly due to the drop in the bootlegging of cigarettes from the two states to Michigan.

As technologies have improved, tax stamps have become more sophisticated. These more sophisticated tax stamps include encrypted information that makes the stamps more difficult to counterfeit and enhances authorities’ enforcement capabilities. Some features of these stamps are clearly visible, such as color-shifting ink, design, and unique stamp numbers. Other features can only be seen with the use of specially designed scanners, including encrypted codes with information on the distributor’s name, when the stamp was applied, and the value of the stamp.

Jurisdictions that use enhanced tax stamps typically adopt related systems that allow them to easily monitor the application of the stamps and the distribution of the stamped products. Similarly, many also adopt licensing requirements for all involved in the production, distribution, or sale of tobacco products, further facilitating the ability of authorities to enforce tax laws.

California was the first U.S. state to adopt the new generation of tax stamps, in 2005. Prior to that, cigarette packets were required to have affixed, heat-applied decal tax stamps purchased from the California Board of Equalization. However, illicit traders were able to use counterfeit techniques to reproduce the stamps and evade the tax (Tang et al., 2009, pp. 165-166). The new digital tax stamps are readable by a scanner and are

encrypted with specified information, including the name and address of the distributor, the date the stamp was affixed, and the value of the stamp. This encrypted information provides board investigators with track-and-trace capability in the field: they can verify the taxes paid by using scanning devices designed to read the encrypted information and detect counterfeit stamps (Tang et al., 2009, p. 166; Horton, 2010, p. 3). The Board of Equalization uses both random and referral inspections of retail outlets (using hand-held scanners) to determine the authenticity of cigarette tax stamps, and it conducts large-scale sweeps of wholesale distributors (Al-Delaimy et al., 2008, pp. 4-14).

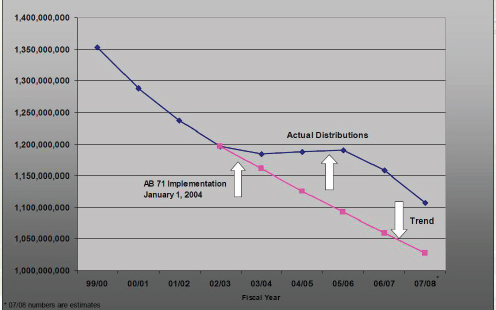

California’s early experiences with the new stamp in 2005, coupled with its licensing requirements (enacted in 2004) and enforcement activities, were positive, with cigarette tax revenues up sharply from forecasts: see Figure 5-2. The early success led California to adopt a further enhanced tax stamp in 2009. Although the tobacco industry has suggested that criminal traders have been able to easily counterfeit the new stamps, the Board

FIGURE 5-2 Cigarette tax revenues in California, fiscal 2000-2008.

NOTES: The left-side arrow reflects the initial adoption and implementation of the new stamps. The middle arrow points to the actual distributions following the implementation of the new stamps. The right-side arrow points to the projected distributions if the underlying trend prior to the implementation of the stamp had continued over time.

SOURCE: Bartolo and Kimsey (2013).

of Equalization indicates that while visual representations or images of California’s tax stamp have been discovered, the tax stamp’s encryption or security features have not been successfully duplicated (Framework Convention Alliance, 2008, p. 9; Horton, 2010, p. 3). More generally, there are “no known reports of any compromises of stamp encryption systems,” and “[t]he application of lost or stolen hybrid tax stamps with unique identification features to unmarked tobacco products could be detected through revenue and customs inspections, or criminal investigations” (Colledge, 2012, p. 8).

In the United States, at the end of 2013, encrypted cigarette tax stamps were being used in Massachusetts and California, and they had been approved for use, but not yet required, in New Jersey; in Michigan, the rollout of digital tax stamps was expected to be completed by the end of 2014.7 Outside the United States, Turkey and Brazil were among the earliest countries to adopt the more sophisticated stamps and related monitoring systems. Others have followed, including the Philippines, which began using the stamps on cigarettes in August 2014 following its 2012 “sin tax” reform legislation, and Canada, which implemented a high-tech excise stamp in July 2012.8

The cost of tax stamps varies considerably, depending on the degree of sophistication. For example, the traditional heat-applied stamp used in California for many years cost less than 50 cents per 1,000 stamps; the first-generation encrypted stamp was more than 10 times as expensive, at roughly $5.00 per 1,000 stamps; and the second-generation encrypted stamp with additional features is still more expensive, at more than $8.00 per 1,000 stamps. The costs can be higher when there are more sophisticated production monitoring systems included. In many jurisdictions, the additional costs are passed on by governments to producers or distributors, who then pass the costs on to purchasers through higher prices. In general, even when the costs are borne by governments, the costs of the stamps, related technologies, and enforcement efforts appear to be cost-effective, with the additional tax revenues that result from improved tax compliance and the reduction in the illicit tobacco trade more than offsetting the increased costs. For example, the cost of California’s digital tax system (in 2008) was estimated at $9 million per year, while the state collected nearly

_______________

7 See http://www.michigan.gov/documents/taxes/StampingAgentsNotice_448510_7.pdf [January 2015].

8 “The [Canadian] excise stamp indicates that federal excise duty has been paid and that product was manufactured legally. It has state-of-the-art visible and hidden identifiers and security features similar to those found on Canadian banknotes, such as unique color-shift ink that changes from red to green when the stamp is tilted. The stamp also has hidden security features that only federal and provincial law enforcement agencies can detect” (Canada Revenue Agency, 2012, p. 1).

$153 million in annual state tax revenues: $87.7 million in the cigarette excise tax, $16 million in excise taxes on other tobacco products, and $49.2 million in state sales and use taxes as a result of the licensing act (described above) and tax stamps (Framework Convention Alliance, 2008, p. 8; Horton, 2010, p. 4). These technologies, combined with enforcement efforts, can be expected to work just as well in higher-tax tax states as in lower-tax ones: in fact, one would expect the payoff to be larger in higher-tax states because since the magnitude of the problem is likely to be larger.

The apparent effectiveness of state-of-the-art tax stamps in increasing excise tax collections suggests that retail compliance with state laws may be sensitive to the ease of enforcement. Better data and research on supply-side networks (see Recommendation 3-1 in Chapter 3) could strengthen the understanding of the risks to retailers of selling illicit products and could help produce estimates of the extent to which retailer compliance responds to particular regulator and enforcement actions.

Track-and-Trace Systems

Encrypted tax stamps and other pack markings are an integral component of more comprehensive tracking-and-tracing systems that both “prospectively” track9 tobacco products through each stage of the supply chain, from production until sale to tobacco users, and that can be used to “retrospectively” trace10 products back through the supply chain so that those involved in production, distribution, and sale can be identified.

Effective track-and-trace systems help to maintain the integrity of the supply chain by strengthening tax authorities’ ability to identify illicit products and to determine the point at which products are diverted from the legal supply chain into illicit markets, enabling the authorities to identify who was in control of those products at that point.

Establishing a global track-and-trace system for tobacco products is a key component of the FCTC Protocol (see also Box 5-1, above). The protocol calls for this system to include the following features:

- unique, secure, nonremovable identification markings (e.g., stamps or codes) to be affixed to or form part of all cigarette packaging;

_______________

9 “Tracking means systematic monitoring by competent authorities or any other person acting on their behalf of the route or movement taken by tobacco products through their respective supply chains of manufacture, sale, distribution, storage, shipment, import or export, or any part thereof” (Joossens, 2011, p. 24).

10 “Tracing means the re-creation by competent authorities or any other person acting on their behalf of the route or movement taken by tobacco products through their respective supply chain of manufacture, sale, distribution, storage, shipment, import or export, or any part thereof” (Joossens, 2011, p. 24).

- markings that include or can be used to identify the date and location of production; the production facility, machine, and production shift or time of manufacture; the name, invoice, order number and payment records of the first customer not affiliated with the manufacturer; the market in which the product is intended to be sold and the intended shipping route, date, destination, point of departure, and consignee; the product’s description, including brand, subbrand, and other information; shipping information; and the identify of known subsequent purchasers; and

- maintenance of appropriate records by all involved in the supply chain.

In 2005, Philip Morris filed a patent for a marking, tracing, and authentication tool for its products that became known as “Codentify.” The four major tobacco producers (British American Tobacco, Imperial Tobacco, Japan Tobacco International, and Philip Morris International) have formed the Digital Coding and Tracking Association (DCTA) in order to promote Codentify. As a track-and-trace system, Codentify is regarded as having serious technical limitations, including its failure to link codes at the pack level with codes at the carton or case level (Joossens, 2011; Joossens and Gilmore, 2013).

Many tobacco control experts have expressed concern about the tobacco industry’s involvement in the development of such a track-and-trace system and regard the industry’s promotion of Codentify violating of Article 5.3 of the FCTC and Article 8 of its protocol, which call for no industry involvement in the establishment of a track-and-trace system (Joossens and Gilmore, 2013). Smaller tobacco manufacturers have also been skeptical of using Codentify, in part because it would require them to provide client and other business data to the major manufacturers or their surrogates. There may also be a security problem with such a system, according to Colledge (2012, p. 12):

[it could present] a potential operational security threat to the integrity of government tax collection and protection. Any system that would include control of data access by the tobacco industry could potentially be compromised by the tobacco industry if it monitored enforcement-related inquiries.

The main objective of tracking and tracing is to facilitate investigations into tobacco smuggling and to identify the points at which tobacco products are diverted into illicit markets (Joossens, 2011). But, according to Colledge (2012, p. 3):

[It can only be used to monitor] tobacco products that are produced under strict controls, including production monitoring and the application of a unique marking system at the point of manufacture. It has limited, if any, application in monitoring the production of tobacco products from illegal manufacturing facilities.

Nevertheless, these technologies could still be used to identify products that have not been properly taxed, even if (in the case of illegally manufactured or counterfeit products) they cannot be traced back through the supply chain. In addition to making it easier to detect contraband at any point in the system, track-and-trace technologies can provide other value to the authorities. For example, they will make it easier for the states to determine how much escrow is owed by each nonparticipating manufacturer under the Master Settlement Agreement.11 Moreover, they can provide a check on retailers’ sales tax reports, since state revenue agents can better identify possibly fraudulent sales tax returns if the state tax department knows exactly how many cigarettes are sent to each retailer each month.

Digital tax stamps and coded information are more effective when implemented in combination with other measures, such as the licensing legislation in California (Framework Convention Alliance, 2008, p. 8). Joossens (2011) also suggests that, rather than individual countries developing their own domestic track-and-trace systems, such systems are best implemented at the international level in order to facilitate tracking and tracking across borders. This issue is exemplified by the Brazilian experience. In 2007, given significant problems with illicit cigarette production, Brazil implemented a track-and-trace system that required the installation of automatic cigarette production counters on every cigarette manufacturing line in the country and the affixation of digital tax stamps on each pack of cigarettes. In 2011, this system was further strengthened when a new law required that cigarettes produced in Brazil for export be marked with a visible two-dimensional matrix code that would allow authorities to trace the date and place of manufacture of the pack and its country of destination. The track-and-trace system is considered successful in that it has curtailed domestic illegal production and controlled manufacturers’ tax evasion in Brazil. Brazilian authorities report that several manufacturing companies have since been closed for noncompliance with licensing rules (including failure to obtain a cigarette manufacturer’s license and failure to pay proper taxes), and there has been a significant decline in tax evasion (Joossens, 2011). Though considered successful on this front, this track- and-trace system has had little to no impact on smuggling originating in

_______________

11 A nonparticipating manufacturer is one that does not participate in the Master Settlement Agreement: see Box 1-3, in Chapter 1.

Paraguay, which remains the main source of illicit cigarettes in Brazil. This situation highlights one of the limitations of country-level track-and-trace systems—namely, that they focus only on domestic licit production and, absent an integrated transnational system, will do little to control the supply of illicit products from other countries.

The benefits of a regional system were recognized by the EU parliament when in February 2014, it approved a revised Tobacco Products Directive that included provisions for implementation of an EU-wide track-and-trace system and anti-counterfeiting measures (Joossens et al., 2014b).12 This directive was motivated by concerns about the levels of illicit trade in the European Union, particularly bootlegging within the EU from lower-tax and lower-price countries and the influx of cheap whites from Eastern Europe.

The situation in the United States is somewhat different from the European Union: nearly all tobacco purchases in the United States are of domestically produced cigarettes. While a domestic (as opposed to a transnational) track-and-trace system in the United States would be largely workable, the comparable issue in the United States is whether a track-and-trace system is state or national. A national system—one that is implemented across state borders—would be better able to track and trace cigarettes through the licit distribution system and identify points of diversion into illicit markets than would systems that are implemented at the state level.13 It is also important to note that low-tax states, such as Virginia, that are the source of many bootlegged cigarettes have limited incentive to adopt digital tax stamps or a track-and-trace system. As the Virginia State Crime Commission (2013a, p. 2) notes: “As almost all data and law enforcement intelligence indicates that Virginia is a source state for trafficked cigarettes, and not a destination state, switching to a digital tax stamp would probably not have a significant impact on Virginia’s tax revenues.” Nevertheless, destination states such as New York would still be able use a state-based system to identify illicit cigarettes, even though it would not provide information on diversions from the licit distribution system across state borders.

_______________

12 These provisions, after being implemented in national legislation, are expected to go into effect in 2016.

13 Canada’s high-tech excise stamp is a federal program, but it cannot be used to detect whether provincial taxes have been paid. Thus, it is not a direct point of comparison for the United States. This reflects the fact that the illicit trade problem in Canada revolves not around interprovince bootlegging, but rather illicit cigarettes from Native reserves (largely confined to Ontario and Quebec).

As discussed in Chapter 2, the illicit tobacco market in the United States is largely driven by interstate bootlegging that exploits tax differentials between the states. States have reasons for maintaining differential tax rates, including the economic benefits of being a source of cigarettes for tax evasion. Nevertheless, states might be willing to coordinate taxes in order to reduce disparities if there were a change in the conditions that led to different tax rates. For example, federal funds could subsidize or incentivize coordination. With respect to Native American tribes, some states have already entered into agreements with them in order to reduce the price disparities that make illegal sales profitable: see Box 5-4.

Although tax harmonization agreements could, in principle, be negotiated to enact excise tax ceilings (i.e., requiring high-tax jurisdictions to reduce taxes in order to align with low-tax jurisdictions), the adverse public health and revenue effects of such a policy may outweigh any positive effects on the illicit market. In contrast, tax harmonization agreements that set a high floor for excise taxes (i.e., requiring minimum levels of taxation while also allowing jurisdictions to levy higher taxes) could reduce the health harms of tobacco, increase revenues for governments, and mitigate illicit activities associated with tax avoidance and tax evasion.

Harmonization agreements that require minimum rates of tobacco excise taxation can also compel governments to levy a particular type of excise tax—specific, ad valorem, or a hybrid of the two; to agree to a minimum tax burden (percentage of excise tax in the price) or a minimum value of tax; and to coordinate regular tobacco tax increases to adjust for inflation and income growth (Blecher and Drope, 2014).14 For example, the European Union requires member states to use a hybrid tax system of both ad valorem and specific excise taxes. As of January 1, 2014, most member states were also required to levy a minimum 60 percent excise tax and a minimum excise tax floor of €90 per 1,000 cigarettes (Blecher et al., 2014), which is about $2.35 per pack.15 It is still too soon to determine the impact of this agreement on bootlegging in the region.

In contrast to the EU harmonization policy, the West African Economic and Monetary Union (WAEMU) tobacco tax harmonization directive, agreed to in 1998, requires a relatively low excise tax rate (15 percent), enforces a tax ceiling on the excise tax rate (45 percent), and levies an ad

_______________

14 Specific taxes are based on quantity while ad valorem taxes are based on the value of the product. Since the value of the tax reflects the product price range, consumers can avoid the impact of ad valorem taxes by switching to less expensive products (Blecher and Drope, 2014).

15 Bulgaria, Estonia, Greece, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, and Poland are not compelled to meet these requirements until January 1, 2018. In addition, the 60 percent excise tax does not apply to countries whose excise tax exceeds €115 per 1,000 cigarettes (Blecher et al., 2014).

BOX 5-4

Tribal Tax Revenue Agreements

In order to provide incentives to Native American and First Nations tribes to impose state and provincial taxes on cigarettes sold on tribal lands, some U.S. states and Canadian provinces have entered into revenuesharing agreements with tribes, in which the tribes receive a portion of the related revenue gained through the imposed tax. These agreements (often known as tribal compacts) are a way of reducing the price disparity that makes illegal sales profitable without having to resolve claims about tribal sovereignty.

Several states have had such taxrevenue sharing agreements in place for some time. Since the 1980 U.S. Supreme Court ruling in Washington v. Confederated Tribes of Colville Indian Reservation, the state of Washington has had the authority to require Native American retailers to keep detailed records of cigarette sales and tax sales to all nonNative Americans who purchase cigarettes. According to the state’s law, Native American retailers are required to collect state excise taxes on all sales made to nonNative Americans, but they may sell untaxed cigarettes to tribal members as long as the seller and buyer know each other personally or the buyer presents a tribal identity card upon purchase.

In 2001, legislation authorized Washington’s governor to enter into cigarette tax contracts with eligible tribes. Many tribes have entered into such contracts, in which tribes may set a tribal cigarette tax comparable to and in lieu of state and local sales and use taxes and state cigarette taxes. The resulting revenue from these tribal taxes can be used for essential government services.a In Canada, the province of Manitoba implemented a similar program, which imposes a “band assessment” on tobacco purchases sold to Native purchasers that is equivalent to the provincial tax. The agreement equalizes the price on and off the reserve for Native purchasers, and the proceeds are given monthly to each “band” (tribal government) by the provincial government, which collects the tobacco tax at the wholesale level (Sweeting et al., 2009).

Wisconsin has a slightly different tax revenue sharing agreement. When a tribe sells cigarettes on a Native American reservation, Wisconsin tax stamps

valorem excise tax (Mansour and Rota-Graziosi, 2013; Blecher and Drope, 2014). According to the International Monetary Fund, the convergence of the countries’ tax systems, particularly the excise taxes on tobacco products, “may have contributed to the positive revenue performance observed in WAEMU member states since 2000” (Mansour and Rota-Graziosi, 2013, p. 37).

The countries of the Southern African Customs Union also enacted a tobacco tax harmonization requirement in 1964. This agreement has been more successful from a tobacco control perspective because it ties regional excise taxes to South Africa’s excise tax, which has increased steadily since the early 1990s. While the tax rate is not as high as that in the European

must be attached to packages sold to nontribal members. Tribal councils in Wisconsin may either purchase untaxed cigarettes to sell to tribal members living on the reservation, or they may enter into an agreement with the Wisconsin Department of Revenue to receive cigarette tax refunds. Under such an agreement, the tribal council may receive a refund of 70 percent of the cigarette taxes paid by authorized cigarette retailers or the tribal council on cigarettes purchased for sale on the tribal land. The tribe may also qualify for a refund of 30 percent of the cigarette taxes collected by authorized retailers to tribal members living on tribal land. The tribal land on which the cigarettes are sold must have been designated a reservation or trust land prior to or on January 1, 1983 (Department of Revenue, State of Wisconsin, 2001). This approach provides an incentive for compliance rather than sanctioning or threatening to sanction noncompliance, although there is no evidence about how salient these incentives (or sanctions) may be to purchasers and others in the supply chain.

In New York, a major agreement has been reached but not yet implemented. In mid2013 Governor Cuomo announced an agreement between the state of New York, the Oneida Nation, and Oneida and Madison counties. The agreement requires the Oneida Nation to charge a sales tax to nonNative Americans that is equivalent to or greater than the combined state and county taxes, as well as to adhere to minimum pricing standards. In addition, the Oneida Nation will be required to put the tax revenue generated from the cigarette sales toward government programs similar to those of the state and counties. The agreement requires approval of the state legislature, both counties, the U.S. Department of the Interior, and the New York State attorney general, as well as judicial approval.b

_____________

aMatheson v. Gregoire, Brief of Respondents No. 350670 (filed October 23, 2006), Washington Court of Appeals. Available: https://www.courts.wa.gov/content/Briefs/A02/350670%20respondent.pdf [April 2014].

bSee https://www.governor.ny.gov/press/05162013agreementwithstateoneidanationandoneidaandmadisoncounties [January 2015].

Union, the agreement does set a tax floor that is relatively high, especially compared with that of WAEMU. Regional harmonization has largely eliminated incentives for bootlegging and cross-border shopping within the Southern African Customs Union. However, illicit cigarette consumption remains a problem—most likely because of illegally manufactured cigarettes from Zimbabwe, which borders the region (Blecher, 2010).

In the past decade or so, the U.S. government has provided states with various incentives to harmonize policies. For example, the U.S. Department of Transportation 2001 Appropriations Act provided an incentive for state-level adoption of a legal limit on impaired driving at 0.08 BAC (blood alcohol concentration); states that did not conform lost highway construction

funds (National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, 2003). Similarly, the government provided funding only to those states that imposed increased minimum age requirements on the purchase of alcohol and tobacco.16 In a major report, the Institute of Medicine (2007) also recommended a federal program to allocate funds in such a way as to give low-tax states an incentive to raise cigarette taxes. Although the enactment of a tax harmonization program in the United States would be politically challenging, it would also address one key “root cause” of the domestic illicit tobacco trade.

We use the term “public education campaigns” to broadly refer to any efforts or combination of efforts aimed at informing the general public or specific professionals and motivating their behaviors. Most of the available research on the effectiveness of public education focuses on mass media campaigns and school-based programs aimed at controlling or eliminating the use of tobacco in general (e.g., Siegel and Biener, 2000; Sly et al., 2002; Emery et al., 2005; National Cancer Institute, 2008; Farrelly et al., 2009; McAfee et al., 2013).

Mass media campaigns have the potential to reach a large number of people. Although there are many limitations to individual evaluations of mass media campaigns, most researchers agree that aggregate findings from controlled field experiments and population studies show that anti-smoking mass media campaigns have been effective and are associated with declines in the number of young people who initiate smoking and with increases in the number of adults who quit (see, e.g., Wakefield et al., 2010). Mass media campaigns have been shown to be effective at decreasing the prevalence of tobacco use across different locations (i.e., different countries) and different population groups (Hopkins et al., 2001; Community Preventive Services Task Force, 2013). Research is beginning to examine the level of advertising required, the types of messages that are most effective, and whether there are any differences among different demographic populations. This research shows that exposure to advertising that elicits negative emotions appears to increase tobacco cessation interest and rates across populations groups, groups that have been heterogeneous with regard to desire to quit, income, and education (White et al., 2008; Borland et al., 2009; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2011; Farrelly et al., 2012a; Azagba and Sharaf,

_______________

16 The National Minimum Drinking Age Act of 1984 required all states to raise their minimum purchase and public possession of alcohol age to 21. States that did not comply faced a reduction in highway funds under the Federal Highway Aid Act (U.S. Department of Transportation, 1999). The Synar Law in 1992 restricted youth access to cigarettes—states that did not comply and raise the cigarette purchase age to 18 lost federal funding for mental health programs (Chaloupka et al., 2011).

2013). Notably, lower socioeconomic populations—which are more likely to be involved in illicit tobacco markets—have been shown to be responsive to strong emotional or graphic advertising.

A few countries have implemented public education campaigns for the specific purpose of lowering demand for or raising public awareness on the illicit tobacco trade. The committee was able to assemble information on campaigns in Canada, Hong Kong, Ireland, Singapore, the United Kingdom, and in Chicago in the United States: see Table 5-1. These public education campaigns were implemented as part of broader strategies to combat the illicit tobacco trade, and each was for a limited time period. For example, the United Kingdom launched a campaign in 2009, the North of England Tackling Illicit Tobacco for Better Health Programme. The overall goal of this program was to reduce the prevalence of smoking in the targeted areas by reducing the availability of illicit tobacco as well as the demand for illicit tobacco. The public education or social marketing campaign was part of this larger program. Other elements included efforts to forge partnerships between enforcement and health agencies and to improve information sharing (UK Centre for Tobacco Control Studies, 2012).

The parties administering public education campaigns have ranged from governments to retailer organizations to advocacy groups. For the most part, these campaigns have targeted disadvantaged communities where the illicit trade is undermining strategies to control the use of tobacco in general. For example, the United Kingdom’s “Get Some Answers” campaign targeted working-class adult smokers ages 25-55, in regions of high use of smuggled cigarettes, who were considered “movable” in their attitudes toward illicit tobacco. Other audiences have included professionals, public figures, and business owners who might have a role in reducing the supply or demand for tobacco. In a few campaigns that appealed to the need for greater enforcement, government agencies were the target audience.

National groups (e.g., Hong Kong United Against Illicit Tobacco and the National Coalition Against Contraband Tobacco in Canada) have urged governments to institute large-scale public education campaigns to reduce demand for illicit tobacco. Critics of public education campaigns on illicit tobacco have argued that they could be ineffective because smokers are already aware of the unhealthiness of cigarettes or because they could have the unintended consequence of implying that legal cigarettes are less harmful (Sweeting et al., 2009).

Many of the campaigns we identified have focused on the health dangers and hazardous content of counterfeit cigarettes, some going to the extent of emphasizing the presence of human feces, dead flies, mold, and insect eggs in seized counterfeit products. However, for the most part, tobacco products that appear in the illicit market are the same as those that appear in the legal market. Research on counterfeit cigarettes to date has

TABLE 5-1 Public Education Campaigns Against the Illicit Tobacco Trade

| Country and Reference | Campaign | Duration | Organizer | |

| Canada (Royal Canadian Mounted Police, 2013) | Contraband Tobacco Enforcement Strategy May 2008 to 2011 | Royal Canadian Mounted Police | ||

|

Goal(s) Raise public awareness about the public safety and health consequences of the illicit tobacco trade. Communication strategies (varies by community)

|

||||

| Hong Kong (Jolly, 2013) | Stop IT | Unknown | Hong Kong United Against Illicit Tobacco (advocacy group) | |

|

Goal(s) Raise public awareness, change attitudes, and draw attention to the problem of illicit tobacco and the need for more robust law enforcement. Communication strategies

|

||||

| Ireland (JTI Ireland Ltd., 2012; Retailers Against Smuggling, 2012) | Smell a Rat | Launched August 2012 | Retailers Against Smuggling | |

|

Goals(s) Raise public awareness of the health dangers of buying illegal cigarettes and change perceptions that cigarette smuggling is a victimless crime. Communication strategies

|

||||

| Country and Reference | Campaign | Duration | Organizer | |

| Malaysia | Rokok Tak Sah (Smoking Void) | Unknown | Royal Malaysian Customs | |

|

Goal(s) Educate retailers and the public about the penalties of buying and selling illicit cigarettes (supplementing increased enforcement efforts to seize illegal cigarettes and administer fines to retailers found facilitating illegal sales). Communication strategies

|

||||

| Singapore (Singapore Customs, 2010, 2011) | Don't Get Burnt | August 2010 to July 2011 | Singapore Customs | |

|

Goal(s) Raise public awareness of the social consequences and severe penalties for buying, selling, or possessing illegal cigarettes that do not bear the required official mark. Communication strategies

|

||||

| Singapore (Singapore Customs, 2012) | 1 IS ALL IT TAKES | November 2012 to June 2013 | Singapore Customs | |

|

Goal(s) Educate the public on the penalties of dabbling with contraband cigarettes. Communication strategies

|

||||

| Country and Reference | Campaign | Duration | Organizer | |

| United Kingdom (Hooper and Baker, 2011) | Counterfeit Kills | 2007/2008 | HM Revenue and Customs | |

|

Goal(s) Reduce the demand for cheap and counterfeit tobacco by raising awareness of the risks of counterfeit cigarettes and toxic ingredients of cigarettes in general. Communication strategies

|

||||

| United Kingdom (Hooper and Baker, 2011) | Dodgy Cigs | 2009 | Department of Health West Midlands and and East Midlands | |

|

Goal(s) Raise public awareness of hazardous contents of counterfeit cigarettes and inform business owners of their liabilities for allowing illicit sales on their premises. Communication strategies

|

||||

| United Kingdom (North England) (UK Centre for Tobacco Control Studies, 2012) | Get Some Answers | June/July 2010 an early 2011 | Department of Health d and Her Majesty's Revenue & Customs | |

|

Goal(s) Persuade the public to get more information on illicit tobacco trade by alerting them to the criminality of the illicit trade as well as increased availability to children. (This campaign purposefully avoided the “greater harms message” to limit the perception that legal tobacco would be seen as healthier.) In a second phase, encourage the public to call Crime Stoppers to report any observed illicit trade. Communication strategies

|

||||

| Country and Reference | Campaign | Duration | Organizer | |

| United Kingdom | Keep It Out | 2012 onward | Tackling Illicit Tobacco for Better Health | |

|

Goal(s) Keep stakeholders informed of the progress to control illicit trade, reduce the demand for illegal tobacco, and alert the public that illicit trade is not a victimless crime. Communications strategies

|

||||

| United States (Chicago) | Check the Stamps | 2014 | Chicago Department of Public Health | |

|

Goal(s) Help prevent illegal sales and supplement efforts to reduce smoking initiation by youth. Communication strategies

|

||||

shown some differences in levels of tar and selected toxicants in comparison with conventional cigarettes, including elevated levels of tar, nicotine, carbon monoxide, lead, cadmium, thallium, and arsenic (Pappas et al., 2007; Chen et al., 2010; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2010), but these elevated levels have not been shown to affect overall toxicity and, based on current evidence, are unlikely to significantly increase the health risk of an already dangerous product (Pappas et al., 2007).

In an effort to address the illicit trade problem while not promoting legal cigarettes as being less harmful, the “Get Some Answers” campaign in the United Kingdom specifically avoided the “greater harms message” and focused on the illegality of counterfeits and their increased availability to children in an effort to address the illicit trade problem while not pro-

moting legal cigarettes as less harmful. A variety of assessment indicators suggest the campaign has reduced demand. However, the findings may be limited because an evaluation was conducted without a control region, and the education campaign was one part of a broader strategy to reduce illicit trade (UK Centre for Tobacco Control Studies, 2012).

The evaluation of the campaign used indicators from the 2009 and 2011 NEMS surveys. During the campaign, the proportion of smokers who had brought back, or had others bring back, duty-free cigarettes from abroad fell from 33 to 27 percent and 27 to 22 percent respectively. Other positive indicators included (1) a decrease in the proportion of smokers who purchased illicit tobacco from 20 to 18 percent; (2) a decline in total market share of illicit tobacco from 9.4 to 8.8 percent; (3) increased awareness of illicit trade among nonsmokers from 54 to 69 percent; and (4) a decline in the proportion of smokers who were “comfortable” with illicit tobacco by 4 percentage points (to 15 percent) and an increase in the proportion “uncomfortable” by 4 percentage points (to 59 percent). The evaluation report also recognized that data from a survey of smoking behavior among young people (ages 14 to 17 years) by Trading Standards North West and NEMS suggested a marked decrease in smoking among young people in the regions (UK Centre for Tobacco Control Studies, 2012).

There is still very little empirical information on the effectiveness of public education campaigns that focus on the illicit tobacco trade. External evaluations have a number of limitations, most notably, that campaigns are often part of broader strategies to combat illicit trade, and the effects of public education campaigns are difficult to separate from those of other strategies. Nonetheless, most assessments and formal evaluations of campaigns find survey respondents who are able to identify or recall elements of the campaigns and report increased public awareness of the illicit trade and its consequences, as well as positive attitudes toward the campaigns. In some evaluations, an increased number of calls to Crime Stoppers or other such hotlines were observed during the campaigns.

If the federal or state governments want to undertake efforts to reduce the size of the illicit tobacco trade, then it is clear that there are a range of interventions that are likely to have at least some effect.

Opportunities exist for governments to control the supply chain and prevent diversion into the illicit market by imposing licensing and regulatory requirements on participants throughout the supply chain, including tobacco growers, manufacturers, distributors, wholesalers, and retailers. In the United States, supply-chain controls imposed at the production and in-transit phases seem to impede diversion into the illicit market. Conversely,

the absence of consistent state regulations and comprehensive federal controls may contribute to the increased diversion seen at the wholesale and retail phases of the supply chain. High-tax and low-tax jurisdictions should be similarly financially motivated to license wholesalers and prevent diversion at this stage of the supply chain. Although it may be difficult to incentivize low-tax jurisdictions to do so, licensing retailers may be particularly important in those jurisdictions.

Digital tax stamps with encrypted information and related track-and-trace technologies also represent a promising approach to combating the illicit tobacco trade by monitoring and controlling the supply chain. These methods have recently been adopted by a number of countries around the world, as well as by California and Massachusetts. The main objective of tracking and tracing is to facilitate investigations into tobacco smuggling and to identify the points at which tobacco products are diverted into illicit markets. Although these technologies would not be able to trace illegally manufactured or counterfeit products through the supply chain, they could still be used to identify (though not investigate) such products as not having been properly taxed.

In order to ensure that tracking and tracing can be facilitated across international borders, track-and-trace systems implemented at the international level are preferable to domestic track-and-trace systems within individual countries. However, this general observation does not imply that a U.S.-based system would be not be useful, since nearly all consumption in the United States is of domestically produced cigarettes. Within the United States, a track-and-trace system that is implemented across state borders (rather than within an individual state) would be better able to track and trace cigarettes through the licit distribution system and identify points of diversion into illicit markets. Low-tax states such as Virginia that are the source of many bootlegged cigarettes have limited incentive to adopt digital tax stamps. Nevertheless, destination states, such as New York, would still be able to use a state-based system to identify illicit cigarettes, even though the states would not be able to investigate diversions across state borders.

Other interventions that have been shown to be effective include those that seek to undermine the conditions that make illegal trade possible by, for instance, harmonizing taxes to eliminate the financial incentive to engage in bootlegging or conducting public education campaigns to reduce consumers’ willingness to buy illicitly traded cigarettes. Although the enactment of a tax harmonization program in the United States would be politically challenging, it would also address one key root cause of the domestic illicit trade: very different cigarette tax rates across states. Public education campaigns aimed directly at the illicit trade also show some promise for reaching lower socioeconomic populations who disproportionately participate in illicit tobacco markets.

Regulations and technologies to control and monitor the supply chain of tobacco products, as well as other interventions to address the conditions that facilitate the illicit tobacco trade, would have limited impact without the effective enforcement of laws prohibiting the illicit trade, which is discussed in the next chapter.