Many factors, both in the United States and elsewhere, give rise to illicit tobacco markets. Cigarettes in the United States and most other countries are subject to high taxes, which create incentives for tax evasion and tax avoidance. Although high tax margins may provide an initial incentive for smuggling and other evasion schemes, other factors—such as the ease and cost of operating in a country, corruption, and the strength of border controls—are also important contributors (Merriman et al., 2000; Joossens et al., 2010, pp. 1,642, 1,646). Illicit tobacco markets can deprive governments of revenue and undermine public health efforts to reduce tobacco use.

The illicit trade refers to “any practice or conduct prohibited by law and which relates to production, shipment, receipt, possession, distribution, sale or purchase, including any practice or conduct intended to facilitate such activity” (World Health Organization, 2013a, p. 6; see also Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act of 2009 [P.L. 111-31]). Unlike some other illicit or illegal1 products, the illicit tobacco market exists in the context of legal markets, and the product itself, tobacco, is not illegal. Thus, in order to understand the illicit market, one has to consider the context of the legal market and the relationship of the two markets.

_______________

1 Although there can be differences in the use of these two terms, they are used interchangeably in this report. Similarly, “licit” and “legal” are used interchangeably.

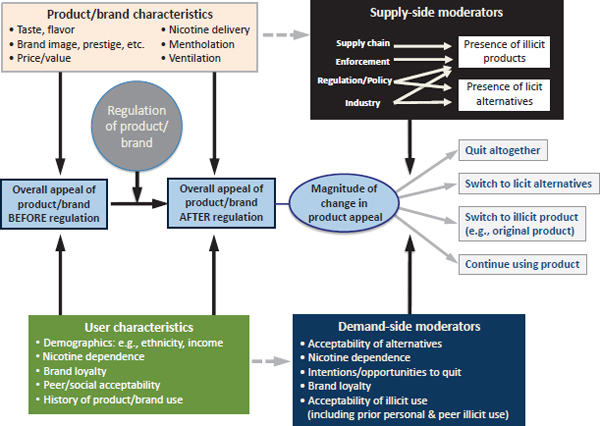

As discussed further below, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) does not have the authority to levy taxes or enforce tax compliance, but it does have the authority to regulate tobacco products so as to improve public health. Such regulations may have an effect on consumer behavior: if the FDA issues product regulations, consumers, in response, may quit smoking, continue using the modified product, switch to a licit alternative, or switch to an illicit product (e.g., the original product, obtained illicitly).

Figure 1-1 presents a model of the dynamic interactions among consumers, licit markets, and illicit markets. The model illustrates that the magnitude of the change in product appeal before and after any given regulation will affect an individual’s choice of the four potential alternatives for tobacco use. The model shows a dynamic state in which complex combinations of product-level factors interact with the characteristics or preferences of individual users to determine the overall appeal of a product. The model also shows the supply- and demand-based moderators that could influence

FIGURE 1-1 Model of factors that influence consumer participation in the illicit tobacco market.

NOTE: Moderators are factors that affect the likelihood that the user will make a particular choice.

BOX 1-1

Statement of Task

The Committee on Law and Justice (CLAJ) in the Division of Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education (DBASSE) of the National Research Council (NRC), in collaboration with the Board on Population Health (BPH) of the Institute of Medicine (IOM), shall convene a committee of approximately fifteen members to assess the scope of the international illicit tobacco market, including demand, structure, volume, variations by country and the impact of changes on policy. The committee shall examine existing literature and consult international experts on the illicit tobacco market. The committee may also examine specific case studies to assess various policy mechanisms and the impact on the illicit trade in tobacco products. The report shall include committee recommendations about the strengths and weaknesses of the currently available research and the applicability of international experiences to the illicit tobacco market in the United States.

the likelihood that a consumer will engage in the illicit market or pursue other product use options.

Because tobacco product regulation could engender illicit markets, particularly for products that would no longer be legal, the FDA has joined with others in the policy and public health communities to study the factors that are likely to determine the extent of such illicit markets and to encourage the development of a research agenda to improve understanding of these factors.

An understanding of illicit markets is important to FDA’s regulatory mission since such markets are among the potential “unintended consequences” that may arise in pursuit of FDA public health goals. To that end, the FDA asked the National Research Council (NRC) and the Institute of Medicine to assess and evaluate the state of knowledge on the global illicit tobacco market, with an emphasis on the lessons that can be learned by the United States.2 The NRC appointed the Committee on the Illicit Tobacco Market: Collection and Analysis of the International Experience to carry out this task; Box 1-1 represents the specific charge to the committee.

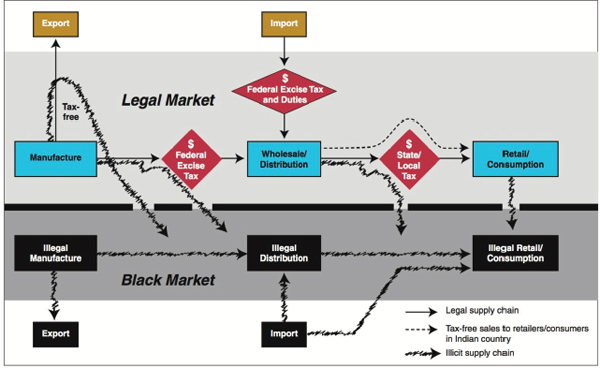

As illustrated by Figure 1-2 and Table 1-1, the diversion of tobacco products into the illicit market can take place in various ways, and the different pathways of diversion can vary in the taxes and fees that are avoided.

_______________

2 Because the illicit tobacco trade largely coincides with the illicit trade in cigarettes, the committee report uses the terms “tobacco” and “cigarettes” interchangeably.

FIGURE 1-2 Opportunities to divert tobacco products into illicit markets.

NOTES: Some domestic websites sell cigarettes that people purchase in a low-tax jurisdiction and resell in a high-tax jurisdiction. Some websites also sell “duty-free” cigarettes (see Ribisl et al., 2001) where the federal excise tax was not paid.

SOURCE: U.S. Government Accountability Office (2011, p. 15).

TABLE 1-1 Illicit Trade Pathways to Evade Taxes and Fees

| Relationship to Supply Chain | Examples of Illicit Trade Schemes | Taxes and Fees Avoided | |||

| Customs Duties | Federal Excise Taxes | State and Local Excise Taxes | MSA/Escrow Payments Under the Master Settlement Agreement (MSA)a | ||

| Import |

|

√ | √ | √ | √ |

| Export |

|

n/ab | √ | √ | √ |

| Manufacture |

|

n/a | √ | √ | √ |

| Wholesale/ Distribution |

|

n/a | Paid | √ | √ |

| Relationship to Supply Chain | Examples of Illicit Trade Schemes | Taxes and Fees Avoided | |||

| Customs Duties | Federal Excise Taxes | State and Local Excise Taxes | MSA/Escrow Payments Under the Master Settlement Agreement (MSA)a | ||

| Retail |

|

n/a | Paid | √ | √ |

| Other |

|

n/a | Paid | Paid | √ |

NOTE: In some wholesale/distribution and retail schemes, state excise taxes are paid in the state where the tobacco products are purchased but unpaid in the state where the tobacco products are illicitly resold.

aSee Box 1-3 for a discussion of the Master Settlement Agreement.

bn/a = not applicable.

SOURCE: U.S. Government Accountability Office (2011, p. 16).

FDA AUTHORITY AND RESPONSIBILITIES

The Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act of 2009 (known as the Tobacco Control Act) gave the FDA comprehensive authority to regulate the manufacturing, marketing, and distribution of tobacco products. Among other things, the law restricts cigarettes and smokeless tobacco retail sales and tobacco product advertising and marketing to youth;3 requires bigger, more prominent warning labels for cigarettes and smokeless tobacco products; and authorizes the FDA to require standards for tobacco products (e.g., tar and nicotine levels) as appropriate for the protection of public health (U.S. Food and Drug Administration, n.d.). Three key sections of the act have particular significance because they provide authority to FDA to regulate specific features of products to reduce consumer demand and reduce harms: product standards (Section 907), new products and substantial equivalence (Section 910), and modified risk tobacco products (Section 911). The FDA’s authority over product standards gives it the power to prohibit or restrict allowable levels of the substances, constituents, and additives that are delivered in finished tobacco products. As long as nicotine levels are not set to zero, the FDA could, in principle, render tobacco products non-addictive by mandating reductions in the nicotine content.

The Tobacco Control Act gives the FDA direct authority over cigarettes, cigarette tobacco, roll-your-own tobacco, and smokeless tobacco, and it enables the FDA to use its rule-making process to assert jurisdiction over other products that are made or derived from tobacco but do not qualify as drugs. In April 2014, FDA issued a proposed rule to extend its tobacco authority to other products, including cigars, pipe tobacco, hookah, and electronic cigarettes. The emergence of electronic cigarettes (or e-cigarettes) as an alternative to conventional cigarettes is discussed in Chapter 8. The law also has a section on the illicit trade that requires the FDA to promulgate record-keeping regulations for the tracking and tracing of tobacco products through the distribution system. However, the Tobacco Control Act does not authorize the FDA to tax tobacco products (U.S. Food and Drug Administration, n.d.).

In addition to the Tobacco Control Act, the key federal laws that address the illegal tobacco trade and product diversion are the Jenkins Act, the Contraband Cigarette Trafficking Act, the Prevent All Cigarette Trafficking Act of 2009 (PACT Act), and the Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act (Alderman, 2012): see Box 1-2. The enforcement of these laws is largely the responsibility of the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco,

_______________

3 The law directs the FDA to issue regulations that, among other things, ban the sale of packages of fewer than 20 cigarettes and limit the color and design of packaging and advertisements.

BOX 1-2

Key Federal Laws Addressing the Illicit Tobacco Trade

Jenkins Act

The Jenkins Act of 1949 requires any person who sells cigarettes across a state line to a buyer, other than a licensed distributor, to report the sale to the buyer’s state tobacco tax administrator. Compliance enables states to collect cigarette excise taxes from consumers. Failure to comply with the Jenkins Act’s reporting requirements is a misdemeanor offense, and violators are to be fined not more than $1,000, or imprisoned not more than 6 months, or both (U.S. Department of the Treasury, 2010). However, prior to the passage of the PACT Act, the Jenkins Act was rarely enforced by the federal government, though some states were successful in using it to combat cigarette purchases over the Internet by state residents (Chaloupka et al., 2011; Alderman, 2012).

Contraband Cigarette Trafficking Act

Enacted in 1978 (and amended in 2006), the Contraband Cigarette Trafficking Act makes it a felony for any person to ship, transport, receive, possess, sell, distribute, or purchase more than 10,000 cigarettes (500 packs) per month that bear no evidence of state cigarette tax payment in the state in which the cigarettes are found. The maximum penalty for violating this law, a felony crime, is 5 years in prison and a fine (U.S. Department of Justice, 2009). The act also contains recordkeeping requirements for any person who ships, sells, or distributes more than 10,000 cigarettes or 500 singleunit cans or packages of smokeless tobacco in one transaction. Violations of reporting requirements, including failure to document the name, address, destination, and vehicle license number of the purchaser, can result in a fine or up to 3 years’ imprisonment.

Prevent All Cigarette Trafficking Act

The Prevent All Cigarette Trafficking Act (PACT Act) of 2009 was intended to regulate Internet cigarette sales and close gaps in the Jenkins Act. The act des-

Firearms and Explosives in the U.S. Department of Justice, the Immigration and Customs Enforcement and Customs and Border Protection agencies in the U.S. Department of Homeland Security, and the Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau in the U.S. Department of the Treasury. In additional, states and localities can enact and enforce laws that govern the illicit tobacco trade. For example, every state has laws with civil and criminal consequences for possessing, transporting, or selling illicit cigarettes. The agencies that enforce these laws are also varied and range from public health and tax and revenue departments to sheriff’s offices and local

ignates cigarettes and smokeless tobacco as U.S. Postal Service “nonmailable” materials. It applies reporting requirements for tobacco taxes to sales, advertising of sales, and the shipping and transporting of cigarettes and smokeless tobacco; regulates (and imposes recordkeeping requirements regarding) the mailing of tobacco products from sellers to customers, including requiring Internet and mailorder sellers to pay all applicable federal, state, local, or tribal tobacco taxes, affix tax stamps before delivery, and check the age and identification of customers at purchase and delivery; authorizes the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives to enter the business premises of delivery sellers and inspect their records and any cigarettes or smokeless tobacco stored at such premises; and expands the powers of state, local, and tribal governments, giving any of these entities that charge a tobacco tax broad enforcement powers and making preemption issues less likely.

The PACT Act imposes a fine or prison term of up to 3 years for violators and increases civil penalties for delivery sellers to the greater of $5,000 for a first violation or $10,000 for any other violation; or 2 percent of the gross sales of cigarettes or smokeless tobacco of the delivery seller during the 1year period ending on the date of the violation. The penalties for a common carrier or other delivery service are $2,500 for a first violation or $5,000 for any violation within 1 year of a prior violation (see Alderman, 2012). The recommended maximum penalties for violations of the Jenkins and PACT Act are lower than federal penalties for violations of major drug trafficking offenses, but they are roughly comparable to recommended sanctions for trafficking in schedule V drugs (standard prescription drugs), which are currently up to 1 year in prison or a $100,000 fine for a first offense and no more than 4 years or a $200,000 fine for a second offense.

Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act

The Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act of 2009 authorizes the FDA to regulate tobacco products. Title III of the law, which deals with tobacco smuggling, sets forth new requirements for labeling, inspection, and records to track merchandise (see Alderman, 2012).

tax boards. The 1998 agreement to settle tobacco-related lawsuits and to recover costs associated with smoking-related illnesses, commonly referred to as the Master Settlement Agreement (MSA), also has implications for cigarette prices and the illicit trade: see Box 1-3.4

_______________

4 According to the U.S. Government Accountability Office (2011), MSA and escrow fees are passed on to the consumer. Based on a cigarette pack bought for $13 in New York City in 2010, these payments amount to $0.56 per pack or roughly 4.3 percent of the price.

BOX 1-3

The Master Settlement Agreement and the Illicit Tobacco Trade

Fortysix states, the District of Columbia, and five U.S. territories reached an agreement with the four largest U.S. tobacco companies in 1998 to settle tobaccorelated lawsuits and to recover costs associated with smokingrelated illnesses: this agreement is commonly referred to as the Master Settlement Agreement (MSA). Since 1998, roughly 50 other cigarette manufacturers have signed on to the agreement as participating manufacturers.

The agreement requires tobacco manufacturers to pay approximately $195.9 billion to the signatory states by 2025, with additional payments continuing after 2025. Payments increase annually to account for inflation, with a minimum increase of 3 percent per year; payments are reduced when participating manufacturers’ combined U.S. cigarette sales or their combined percentage share of the total U.S. cigarette market falls below 1997 levels (Campaign for TobaccoFree Kids, 2003). The U.S. cigarette sale levels used to calculate settlement payments from participating manufacturers to the states are based on the quantity of tobacco products for which federal excise taxes were paid. Cigarettes diverted to the illicit market, which evade federal excise taxes, are not counted in total cigarette sales, thereby reducing manufacturers’ payments. For example, the Massachusetts Attorney General’s Office estimates that for every 1 million federally untaxed cigarettes in his state, the state loses about $1,000 of its MSA payment (Massachusetts Commission on Illegal Tobacco, 2014).

As part of the agreement, 46 states, the District of Columbia, and five U.S. territories enacted a “qualifying statute.” The statute requires nonparticipating manufacturers (NPMs)—those who did not sign the MSA—to make annual payments into a qualified escrow account. The escrow payments effectively eliminate any cost advantage NPMs would have against participating manufacturers and ensures that the NPMs bear some burden for the health costs that cigarette smoking imposes on states. The payment amounts are based on the quantity of product for which each state collects excise taxes. Therefore, cigarettes for which state excise taxes are not collected are not counted in the cigarette sales numbers used to determine each state’s escrow payment.

The qualifying statute also contains language requiring states to “diligently enforce” this statute; failure to do so makes states potentially liable for reductions in their settlement payments from participating manufacturers, known as the “NPM adjustment” (Campaign for TobaccoFree Kids, 2003). If the participating manufacturers’ lost market share is a result of lax enforcement of escrow payments (i.e., states are not diligently enforcing the enacted qualifying statutes), participating manufacturers can claim they are entitled to an NPM adjustment. In an arbitration regarding such claims, participating manufacturers charged a number of states with not enforcing escrow payments on nontaxed cigarette sales. They argued that smuggled products for which escrow is not paid entitled them to payment reductions. The arbitrators found in favor of some states but against others, and several states settled. Thus, states may have an additional incentive to bolster enforcement and reduce cigarette tax avoidance and evasion in order to reduce the risk of an elimination or reduction in their annual MSA payments through litigation (Massachusetts Commission on Illegal Tobacco, 2014).

In contrast with many other commodities, taxes comprise a substantial proportion of the retail price of cigarettes in the United States and most other nations. Cigarette taxation is a powerful, straightforward, and widely used way for governments to raise the price that consumers pay for cigarettes. From a purely economic standpoint, taxes that raise the price of cigarettes are socially desirable in that they discourage smoking while at the same time generating government revenues. However, this can also create incentives for tax avoidance and tax evasion.

Tax avoidance consists of legal activities and purchases—mostly by individual tobacco buyers—that are in accordance with customs and tax regulations (International Agency for Research on Cancer, 2011, p. 298). It includes cross-border shopping, tourist shopping, duty-free shopping, and Internet and other direct purchases (e.g., through the mail or over the phone). Tax avoidance typically involves consumers who legally purchase tobacco for their own use from a jurisdiction with lower taxes than their home jurisdiction.

For example, consumers can travel to nearby states, provinces, or countries with relatively low taxes to pay lower prices for tobacco for their own use.5 Typically, jurisdictions determine whether or not a tobacco purchase is for personal consumption using quantity rules (e.g., two cartons). Consumers can also avoid paying higher taxes in duty-free shops or on Native American reservations (in the United States) and Native reserves (in Canada), where some or all taxes are not levied. Manufacturers may also change product characteristics or descriptors in an attempt to pay lower excise taxes: for example, some U.S. small cigar manufacturers began producing heavier cigars by adding weight to the filter in order to qualify for the lower tax rate on large cigars.

Tax evasion consists of illegal methods of circumventing tobacco taxes. It may be undertaken by individuals as well as by criminal networks or other such organizations or entities. It includes small-scale smuggling (commonly referred to as bootlegging), large-scale smuggling, and illegal production (International Agency for Research on Cancer, 2011, pp. 298-299). Bootlegging refers to the legal purchase of cigarettes in one jurisdiction and their consumption or resale in another jurisdiction without the payment of applicable taxes or duties (Merriman et al., 2000, p. 366). Large-scale smuggling occurs when cigarettes are sold without the payment of

_______________

5 Although many states require purchasers to pay a “use tax,” usually assessed on out-of-state purchases, as well as on items ordered through the mail, by phone, or over the Internet from other states, that use tax is typically assessed at the same rate as all applicable taxes, including excise and sales taxes, that would have been owed had the same goods been purchased in the purchaser’s state of residence.

any taxes or duties, even in the country of their origin (Merriman et al., 2000, p. 366). Illegal production involves the manufacturing of cigarettes in violation of the law: the main forms of illegal production are unlicensed or underreported production of legitimate tobacco products and the production of counterfeit cigarettes (where brand labels are used without the permission of the trademark owner).

Tax evasion can also include smaller-scale efforts, such as individuals’ purchase of tobacco products online without paying their jurisdiction’s sales and excise taxes or individuals’ purchase of tobacco products from neighboring lower-tax jurisdictions that exceed permitted quantities. In the latter situation, consumers may not be aware that they are purchasing more than the legally allowed amount of out-of-state cigarettes, or that appropriate taxes on Internet sales have not been paid.6 Many activities that may appear to be tax avoidance would technically be regarded as tax evasion—albeit on a small scale—given that most states have use taxes that require consumers to pay the appropriate local tax (or the difference between local tax and the tax they paid), though those taxes are little advertised and rarely enforced.7 The situation is a bit different in other parts of the world. In the European Union (EU), for example, there are fairly generous allowances on how much someone can buy in a lower-tax jurisdiction for consumption at home.8

The illicit trade that is of more concern to policy makers involves larger-scale and longer-distance smuggling of tobacco products across tax jurisdictions in order to evade paying taxes; the net social returns from reducing large-scale smuggling are almost certainly higher than from reducing individual tax evasion. In the United States, cigarette taxes vary widely across states, and smuggling operations have exploited these differences, particularly along the I-95 corridor in the eastern United States. In this area, cigarettes are purchased in large quantities in a low-tax state and transported for resale in a higher-tax state. Similar operations can exploit differences between countries.

_______________

6 Y. Chen (2008) notes: “[O]nce the [cigarette] packs are delivered, few consumers remit the owed taxes. . . . Some do not realize they are still required to pay taxes on Internet purchases, while others take a more generally cavalier attitude toward the law.”

7 As described in Box 1-2 (above), the Jenkins Act (as amended by the PACT Act) imposes federal tax reporting requirements on vendors.

8 Cigarettes for which duty and tax have been paid in one EU member state can be brought to another member state in unlimited amounts as long as they are for personal use or as a gift. However, under EU law, customs officers may ask questions and carry out checks if they believe the goods may be for commercial use. The EU directive mandates that the levels that trigger the questioning must not be lower than 800 cigarettes, but member states can set a higher threshold level for customs checks. See Article 32, Council Directive 2008/118/EC, available: http://www.hmrc.gov.uk/customs/arriving/arrivingeu.htm#1 [January 2015].

Both tax avoidance and tax evasion reduce the overall amount of revenue generated by a given tobacco tax in high-tax jurisdictions,9 and they also mitigate the positive effects of tobacco taxes on cessation of tobacco use. Whether or not consumers avoid or evade taxes is an important distinction, and this report—like most discussions of illicit trade—is primarily interested in the latter. Unfortunately, the evidence from most studies reflects a combination of tax avoidance and tax evasion. It is often very difficult to discriminate between smuggled goods, legal cross-border purchases, and illegal cross-border purchases. For example, current survey questions are not detailed enough to distinguish between low-tax cigarettes acquired through formal and informal channels. And studies that are based on discarded cigarette packages (see Chapter 4) that have out-of-state tax stamps cannot distinguish among tax avoidance, tax evasion, tourism, and commuting patterns.

Recent estimates indicate that about 11.6 percent of global cigarette consumption is illicit—or 657 billion illicit cigarettes annually (Joossens et al., 2010). Using its own calculations and reasonable estimates derived from other methods, the committee determined that the percentage of the total market represented by illicit sales in the United States is between 8.5 percent and 21 percent. Nationally, the percentage represents 1.24 to 2.91 billion illicit packs of cigarettes. Of course, the illicit tobacco market is not evenly distributed across the country. It may be as high as 45 percent in high-tax states, such as New York and Washington, while in other states participation in the illicit tobacco market appears to be extremely low (see Chapter 4).

The illicit tobacco trade, like most illicit activity, is dynamic in nature. For example, according to Joossens and Raw (2012), 25 years ago the global illicit trade was dominated by the large-scale smuggling of cigarettes: containers of cigarettes were exported (legally and duty unpaid) only to then disappear into the contraband market. Since then, however, the illegal production of cigarettes has become an increasingly important component of contraband activity in many parts of the world, and policy measures that may have effectively addressed the smuggling of legally manufactured cigarettes in the 1990s may be less effective in dealing with problems of counterfeit and other illegally produced cigarettes.

_______________

9 Although revenues will be higher in low-tax jurisdictions because of avoidance and evasion, the magnitude of this increase will be smaller than the magnitude of the revenue decline in high-tax jurisdictions.

The adverse health impacts of tobacco use are well documented and indisputable (Institute of Medicine, 2007). More than 20 million Americans have died as a result of smoking since 1964. Most were adults with a history of smoking, but nearly 2.5 million were nonsmokers who died from heart disease or lung cancer caused by exposure to secondhand smoke. If smoking persists at the current rate among young adults in the United States, 5.6 million of today’s Americans who are now younger than 18 years of age are projected to die prematurely from a smoking-related illness (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2014, p. 1). Global figures are even more staggering. According to the World Health Organization, tobacco kills nearly 6 million people each year; 600,000 of those deaths are the result of the exposure to secondhand smoke by nonsmokers. If current trends continue, the global annual death toll could rise to more than 8 million by 2030 (World Health Organization, 2014).

Given the grave public health threat presented by tobacco use, governments worldwide and across localities have instituted measures to reduce or eliminate tobacco use among their citizens (e.g., higher taxes, bans on tobacco advertising, and public health warnings). The illicit tobacco trade undermines these tobacco control policies by increasing the affordability and accessibility of tobacco products (see, e.g., Chaloupka and Warner, 2000; Joossens et al., 2000; Carpenter and Cook, 2008; West et al., 2008; Joossens et al., 2010). For example, one study in the United Kingdom estimated that the price of smuggled tobacco products was about 50 percent of the duty-paid equivalent (West et al., 2008, p. 1028). The availability of these lower-priced cigarettes erodes the benefits of tobacco tax measures—and this takes on additional importance given that the price of cigarettes influences youth smoking to an even greater extent than it influences adult smoking (Chaloupka and Warner, 2000; Carpenter and Cook, 2008). It has been hypothesized that the supply of contraband cigarettes may have the effect of depressing cigarette prices across the board: one estimate is that eliminating the illicit tobacco trade would result in an average price increase of approximately 4 percent in all countries (Joossens et al., 2010). In addition, internationally smuggled cigarettes are less likely to carry appropriate health-warning labels (Joossens et al., 2000).

By undermining the effect of tax measures on tobacco product price and use, the illicit trade has resulted in greater accessibility and consumption of cigarettes, especially among poor people and young people; this, in turn, has increased smoking and tobacco-related diseases. One estimate is that eliminating the global illicit tobacco trade would save approximately 164,000 lives in 2030 and annually thereafter—with 32,000 lives saved in high-income countries and 132,000 in low- and middle-income countries

(Joossens et al., 2010). A similar study for the United Kingdom estimated that eliminating the illicit tobacco trade would result in an annual reduction of 4,000-6,500 smoking-related deaths every year (West et al., 2008).

The illicit tobacco market also results in the loss of government revenues. In the United States, these losses are especially incurred by the states: at least $2.95 billion were lost in state tax revenues in 2010-2011. However, this figure masks significant variation among states. Some, such as New Hampshire, see large tax revenue gains, while others, such as New York, see large tax revenue losses (see Chapter 4). On a global scale, it has been estimated that governments lose $40.5 billion a year due to cigarette smuggling (Joossens et al., 2010). Despite the revenue losses caused by tax evasion and avoidance, however, evidence from Canada, France, Sweden, and the United Kingdom suggests that higher taxes could still lead to increases in revenues (Joossens et al., 2000, pp. 400-402; International Agency for Research on Cancer, 2011). That is, even though tax avoidance and tax evasion might increase in response to higher taxes, the losses from those actions would be less than the gains from higher taxes.

THE ROLE OF THE TOBACCO INDUSTRY

As noted by the Institute of Medicine (2007, p. ix), the tobacco industry10 has acted to impede and undermine various tobacco control measures:

Although many social, economic, and political factors have played a role [in prolonging the tobacco problem], perhaps the most important one is that the tobacco industry obscured the addictive properties and health risks of smoking, impeded and delayed many tobacco control interventions, and has so far successfully thwarted meaningful federal regulatory measures.

The tobacco industry has also been at least partly complicit in the global illicit tobacco trade (see Chapter 3).11 The smuggling of legally manufactured cigarettes is a way of introducing the industry’s products into new markets and of expanding its share in existing markets. Moreover, one of the tobacco industry’s principal arguments against increased tax rates and more stringent regulatory changes is that such measures will

_______________

10 Although this report refers to the “tobacco industry,” the committee recognizes that the industry is not a unitary actor, but rather consists of many firms with various interests. The committee also recognizes that tobacco companies may face substantial collective action problems in supporting political action in their common interests.

11 Although many claims have been made regarding the relationship between the illicit tobacco trade and terrorism, the link between the U.S. illicit tobacco market and terrorism appears to be minor, and there is no systematic evidence of the ties that may exist between the global illicit tobacco trade and terrorism: see Chapter 3.

fuel the growth of the illicit tobacco market (see, e.g., Smith et al., 2013), although industry-sponsored estimates of the size of the illicit market tend to be inflated (see Chapter 4). More generally, concerns have been raised about the quality and transparency of industry-funded research on the illicit tobacco trade.12

Concerns over financial conflicts of interest apply not only to the research and the data provided by the industry on the illicit trade but also to the industry’s relationship with law enforcement. The impartiality and objective disposition of law enforcement recently came into question when INTERPOL applied for observer status to the Conference of Parties (COP) to the World Health Organization Framework Convention on Tobacco Control. A recent partnership between INTERPOL and Philip Morris International (PMI), which involved PMI’s contributing 15 million euros toward INTERPOL’s Fund for a Safer World, raised concerns over potential financial conflict of interest. Specifically, the PMI donation was earmarked, in part, to coordinate information gathering, officer training, and the development of procedures to identify illicit products (Framework Convention Alliance, 2012). To many involved in tobacco control, the tobacco industry seemed oddly placed to support law enforcement activities when the industry itself had been complicit in such criminal efforts in the past. The donation cast a shadow over INTERPOL’s application to the COP process and raised questions over its motivations, especially since the industry is not invited to nor is party to this intergovernmental negotiation process, and the COP process had recently resulted in a protocol to address illicit trade of tobacco.

The tobacco industry has also actively worked with law enforcement in the United States to combat the illicit trade—which has raised questions about the motivation for providing such assistance. As detailed in Chapter 3, although sales of counterfeit cigarettes result in financial losses for tobacco companies, the tobacco industry can still benefit from other aspects of the illicit tobacco trade.

The illicit tobacco trade in the United States and across the world clearly has important consequences. Opportunities exist for governments to reduce the size of the illicit tobacco market by targeting particular points of diversion and, more generally, by undermining the conditions that make the

_______________

12 For example, an examination of industry-funded studies on the potential impact of regulatory changes on the illicit trade, conducted by Transcrime of the Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore in Milan, raised questions of neglecting contradictory evidence and making assertions not supportable by available evidence (Fooks et al., 2013).

illicit tobacco trade possible. An examination of international experiences demonstrates that many possible policy interventions and enforcement mechanisms can be implemented for this purpose—and that the challenges presented by the illicit tobacco trade are not unique or insurmountable.

Understanding international experiences with the illicit tobacco trade can provide important insights into the nature of the U.S. illicit tobacco trade, the challenges that may arise in the future, and the effectiveness of policy interventions that may be adopted in response to current and future challenges. If product regulation in the United States spurs demand for illicit products, the nation’s illicit tobacco market could change significantly—producing new market characteristics (e.g., illegal imports may become more important relative to interstate bootlegging) and new points for intervention (e.g., border and customs enforcement may become more important relative to interstate coordination). The findings from international experience will contribute to understanding and responding to such changes in the United States.

The remaining seven chapters of the report detail various aspects of the illegal tobacco market, the policy responses to it, and the data and research that may lead to deeper understanding of that market.

The next two chapters describe the supply and demand characteristics of the market. Chapter 2 explores some of the market’s key features: the cigarette supply chain (with overlapping legal and illegal components), the major illicit procurement schemes, the role of price and nonprice factors in driving illicit trade, and the profitability associated with the illicit market. Chapter 3 turns to the participants in the market: criminal networks, the tobacco industry, terrorist organizations, and the users of illicit tobacco. Among consumers, youths represent a special case because for them, unlike for adults, all purchases of tobacco are illegal. Thus, issues relating to youth access to illicit tobacco are largely embedded in the context of access to legal tobacco.

Chapter 4 describes and assesses methodologies for estimating the size of the illicit tobacco market. It includes the committee’s estimates of the size of the illicit market in the United States.

The next three chapters explore interconnected aspects of policy interventions in the illicit tobacco market. Chapter 5 looks to controlling the supply chain, tax harmonization, and public education campaigns. Chapter 6 focuses on law enforcement at the federal and state levels, with case studies of Virginia and New York. Chapter 7 turns to international case studies, considering the experiences of Spain, the United Kingdom, Canada, and the European Union in policy interventions.

Lastly, Chapter 8 considers the demand and supply responses to possible changes in tobacco products. Those include product design, menthol and other constituents of cigarettes, nicotine levels, health warnings, and packaging. The chapter also considers the role of e-cigarettes as an emerging alternative to traditional tobacco products.

Throughout the report, the committee offers recommendations for data collection and research that could further understanding of the illicit market today and its possible evolution in the future.